Abstract

Background

Hospice and palliative care nursing (HPCN) in China is mainly available at public primary care institutions, where nursing homes (NHs) are rarely involved. Nursing assistants (NAs) play an essential role in HPCN multidisciplinary teams, but little is known about their attitudes towards HPCN and related factors.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was designed to evaluate NAs’ attitudes towards HPCN with an indigenised scale in Shanghai. A total of 165 formal NAs were recruited from 3 urban and 2 suburban NHs between October 2021 and January 2022. The questionnaire was composed of four parts: demographic characteristics, attitudes (20 items with four sub-concepts), knowledge (nine items), and training needs (nine items). Descriptive statistics, independent samples t-test, one-way ANOVA, Pearson’s correlation, and multiple linear regression were performed to analyse NAs’ attitudes, influencing factors, and their correlations.

Results

A total of 156 questionnaires were valid. The mean score of attitudes was 72.44 ± 9.56 (range:55–99), with a mean item score of 3.6 ± 0.5 (range:1–5). The highest score rate was “perception of the benefits for the life quality promotion” (81.23%), and the lowest score rate was “perception of the threats from the worsening conditions of advanced patients” (59.92%). NAs’ attitudes towards HPCN were positively correlated with their knowledge score (r = 0.46, P < 0.01) and training needs (r = 0.33, P < 0.01). Marital status (β = 0.185), previous training experience (β = 0.201), location of NHs (β = 0.193), knowledge (β = 0.294), and training needs (β = 0.157) for HPCN constituted significant predictors of attitudes (P < 0.05), which explained 30.8% of the overall variance.

Conclusion

NAs’ attitudes towards HPCN were moderate, but their knowledge should be improved. Targeted training is highly recommended to improve the participation of positive and enabled NAs and to promote high-quality universal coverage of HPCN in NHs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Hospice and palliative care nursing (HPCN) should be integrated into nursing services to improve the quality of life for the elderly with the tough challenge of the ageing population. In China, more than 264 million adults were aged 60 years old and older in 2020, which is more than 18.70% of the total population [1]. To meet the growing demand for elderly care, nursing homes (NHs) are becoming increasingly common locations for end-of-life (EOL) care [2]; more than one in five deaths globally occurs in NHs [3]. Over the past decade, the number of NHs in China has increased more than fifteen-fold, with approximately 758 currently [4]. This may be related to an increasing elderly population living alone, expanded life expectancy, and weakening of home-based care [2]. Thus, HPCN has been widely advocated in many countries to improve the quality of life for NH residents [5].

NHs mainly serve older, dependent adults in need of complex care with incurable chronic illness, advanced cancer, cognitive impairment, trauma, and other health conditions [6]. Although death is not necessarily imminent, many inpatients require HPCN upon admission because of mortality trajectories associated with chronic disease and frailty [7]. HPCN can improve quality of life for patients and their families by preventing and relieving suffering, reducing the side effects of treatment, and providing social, psychological, and emotional support. As more than 40 million (18%) of the elderly in China are disabled and semi-disabled [8], the ever-growing demand for NHs has increased the need for HPCN [3]. Researchers have suggested that HPCN in NHs are associated with resident and family satisfaction, rational allocation of resources, and lower hospitalisation rates [9,10,11].

The significance of HPCN in NHs is widely recognised by managers, nursing staff, residents, and family members [12,13,14,15]. However, HPCN in China is mainly available at public primary care institutions and a few secondary and tertiary hospitals; NHs are rarely involved [16]. Concern about HPCN delivery in NHs has aroused global awareness as several barriers to care have been identified. For instance, most NH residents’ deaths are unpredictable, making it difficult to determine the appropriate time to provide HPCN [17]. In addition, declines in communication skills and cognitive function often prevent NH residents from expressing their needs accurately [18]. Knowledge deficit is another main challenge for providing HPCN [19], making early integration of HPCN particularly difficult.

Globally, the shortages of qualified nurses and increased demands associated with the ageing population have led to an increase in unregulated healthcare workers and related services [20]. In NH settings, nursing assistants (NAs) are the primary workforce; they provide most life care, such as helping with feeding, excreting, bathing, and communication, and NAs are the people residents see and interact with the most [21]. In addition, NAs offer spiritual support while communicating with family members and strengthening bonds among residents, family members, and medical staff. Overall, NAs are best placed to identify and support residents’ diverse needs [22] and in the absence of multidisciplinary professionals, play multiple roles in HPCN teams [23].

In China, most NAs are organised by companies without unified management standards or comprehensive training mechanisms [24]. Despite the variation in education, training and qualifications across countries, inadequate training for NAs become a global concern [20], particularly for HPCN. Poor care may aggravate the recurrence and deterioration of diseases, and even cause adverse events, creating a weak point in current elderly care [25]. The importance of HPCN is gradually being recognised, bringing with it demands for competent NAs with favourable attitudes, better knowledge, and the skills necessary to provide high-quality services; these changes can improve residents’ quality of life [26, 27].

However, relatively few studies have assessed the current HPCN attitudes of NAs, which may hinder the extension of HPCN to NHs. Given this gap, we introduced a scientific and indigenised scale to evaluate HPCN attitudes among NAs in NHs, identify associated influencing factors, better understand issues that affect NAs’ attitudes; we hope to facilitate the extension of HPCN and propose countermeasures and suggestions for targeted training to promote the provision of high-quality HPCN in NHs.

Methods

Study design and aims

A cross-sectional study was conducted to evaluate NAs’ HPCN attitudes and their associated factors.

Setting and sample

Using purposive sampling, we surveyed five NHs from five districts in Shanghai, including three urban and two suburban areas and two private and three public NHs. Based on the principles of informed consent, voluntariness, and anonymity, NAs were recruited from the selected NHs. Considering that the sample size should be 5 to 10 times the number of items (20 items in the attitude scale), a total of 165 questionnaires were distributed. The inclusion criteria were: (1) formal NAs, (2) having a minimum of one year of experience in NHs, and (3) fully understanding the content of the questionnaire. The exclusion criteria were NAs who were on leave during the investigation or who were reluctant to participate. After excluding invalid questionnaires, 156 questionnaires were analysed, with an effective response rate of 94.55%.

Measurements

NAs’ attitudes and related indicators were measured using a scientific scale modified by Shu et al. [28] and Jing et al. [29] that was based on the Frommelt Attitude Toward Care of the Dying Scale (FATCOD) [30] as well as Liu et al.’s attitude questionnaire [31]. In the original study [29], the scale was proven to have good reliability and validity, with a Cronbach’s alpha reliability coefficient of 0.768 and a chi-square value of KMO 0.624. In this study, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.785, and the KMO was 0.776. The questionnaire was composed of four parts: demographic characteristics, attitudes (20 items with four sub-concepts), knowledge (nine items), and training needs (nine items).

The demographic section comprised 13 questions, including age, gender, marital status, educational level, religious beliefs, professional title, HPCN-related experience, and location and type of NHs. The attitude questionnaire consisted of four sub-concepts: perception of the threats from the worsening conditions of advanced patients (four items), perception of the benefits for the life quality promotion (four items), perception of the benefits for better death preparation (four items), and perception of the barriers to providing hospice care (four items). Each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and the total score ranged from 20 to 100. Negative items (sub-concepts 1 and 4) were reverse-scored. A higher score signified more positive attitudes towards HPCN. Score rate = actual score / total score × 100%. The Knowledge section included nine items. Each item was answered with 1 (true), 2 (false), or 3 (uncertain). Responses were scored as 1 (correct) or 0 (incorrect), and the total score ranged 0–9. A higher score indicated a better understanding of knowledge. The section on training needs contained nine items using a five-point Likert scale. Responses ranged from “completely unnecessary” to “completely necessary” on a scale of 1 to 5, respectively. A higher score indicated a more urgent need for HPCN training.

Data collection procedure

Data collection occurred between October 2021 and January 2022. Electronic questionnaires were issued to NAs who could read and complete the questionnaire independently, and face-to-face questionnaires were used for those who could not complete the questionnaire independently. Participants were given written or oral explanations of the purpose and procedures of the study. After the data collection, the quality controllers performed a logic check.

Data analysis

Means and SD were used to describe continuous variables, and frequencies (n) and percentages (%) were calculated for categorical variables. The data analysis consisted of two parts. Potential factors influencing attitudes were first identified using independent-sample t-tests and one-way ANOVA. Pearson’s correlations were performed to examine the relationships between attitudes, knowledge, and training needs. Next, the attitude score was treated as a continuous variable in a multiple linear regression analysis using all factors significantly associated with the attitudes. The significance level was set at 0.05 (2-tailed). All data were analysed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 23.0).

Results

General information and characteristics of participants

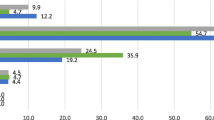

Most of the 156 NAs were female (84%). The mean age was 50.8 years (range 30–67 years), with 74.4% aged over 50 years. The majority had graduated from junior high school and below (78.8%). For marital status, 93.6% of participants were either married or unmarried. More than half had professional titles (64.7%), and 80.8% reported no religious beliefs. Approximately 85% of respondents had experienced caring for dying residents or family members and witnessed the death process of EOL residents, and about 70% provided HPCN for residents. In addition, nearly half (49.4%) were exposed to knowledge related to HPCN, and 37.8% reported previous training experience with HPCN. Among all participants, 120 NAs (76.9%) were from urban NHs and 52.6% were from private NHs (Table 1).

HPCN, hospice and palliative care nursing; NH, nursing home.

Attitudes towards HPCN

The mean attitude score of respondents was 72.44 ± 9.56 (range: 55–99) out of 100, with the mean item score of 3.6 ± 0.5 (range: 1–5). Sub-concept 2 (perception of the benefits for the life quality promotion) had the highest score (81.23%), and its mean item score was 4.1 ± 0.7; meanwhile, whereas sub-concept 1 (perception of the threats from the worsening conditions of advanced patients) had the lowest score (59.92%), and its mean item score was 3.0 ± 0.9. When examining each item separately, the most positive item was item 14: ‘HPCN can help medical staff to take care of patients better’ (4.26 ± 0.85, 85.12%), and the most negative item was item 2: ‘advanced patients with the worsening conditions are hopeless for the cure’ (2.80 ± 1.16, 55.90%) (Table 2).

Factors influencing attitudes regarding HPCN

The average response accuracy of HPCN knowledge was 61.1%, with a total score of 5.5 ± 2.3 (range: 0–9); but the training needs section was scored as 34.43 ± 6.95 (range: 9 ~ 45), with a proportion of 95.5%. A moderate positive correlation showed that attitudes towards HPCN were more positive as knowledge scores (r = 0.46, P < 0.01) and training needs increased (r = 0.33, P < 0.01). The univariate analysis suggested that better attitudes were associated with a marital status of divorced or widowed (P < 0.01), exposure to related knowledge of HPCN (P < 0.01), training experience in HPCN (P < 0.001), and suburban location (P < 0.01) (Table 1). To identify the predictors of NHs’ attitudes towards HPCN, variables with statistical significance were entered into the multiple linear regression model. The significant predictors of attitudes were marital status (β = 0.185), training experience in HPCN (β = 0.201), location of NHs (β = 0.193), knowledge of HPCN (β = 0.294), and training needs for HPCN (β = 0.157), which explained 30.8% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 0.308, P < 0.05). Being divorced or widowed, training experience in HPCN, better HPCN knowledge level, higher HPCN training needs, and suburban location were all significantly and positively associated with attitude scores (Table 3).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the attitudes and factors related to HPCN among NAs in NH settings in China. Although an increasing number of older adults need high-quality HPCN in NHs, and NAs are the main providers, we found that limitations still exist in their attitudes and knowledge regarding HPCN. The findings will not only clarify NAs’ attitudes towards HPCN but also suggest targeted training and enabling facilitators for the extension of HPCN to NHs, in which HPCN should be provided but rarely involved. Policymakers can formulate policies based on the results of this study to ensure high-quality HPCN for all EOL elderly patients.

Our study revealed that NAs in NHs had moderate attitudes towards HPCN. The overall scoring rate was 72.44%, which is slightly lower than that reported in a previous study in Shanghai (volunteers of HPCN, 74.54%) [29] and in Taiwan (long-term care staff of advanced dementia, 73.7%) [32]; however, the rate was higher than a study conducted in Canada (long-term care workers of EOL palliative care, 70.6%) [33]. These differences are likely attributable to international cultural differences regarding life and death, related training, lack of related studies on NAs, and differences in scales.

Generally, NAs fully recognised the benefits of HPCN in NH settings. They agreed that HPCN could positively affect EOL residents, reduce pain, and enhance dignity. Nevertheless, most NAs felt negatively when faced with the worsening conditions of advanced residents and were unable to face the dying process and distress, which is consistent with previous findings [34]. This may be related to death taboos in China. Participants in this study provide personal care for terminal residents in NHs, where deaths occur regularly and are prone to negative emotions, which makes it difficult for NAs to provide high-quality care. Furthermore, these negative views may affect the motivation of NAs to continue their nursing careers and have profound consequences for the provision and extension of HPCN.

In terms of NAs’ knowledge of HPCN, the average response accuracy of HPCN knowledge was 61.1%, which is significantly lower than that of a Chinese study involving volunteers (82.1%) [29], a Taiwanese study involving long-term care staff (62.3%) [32], and an Australian study involving dementia care staff (62.5%) [35]. The results highlight that NAs’ knowledge was disproportionate to their important role in the team, impeding their ability to provide high-quality HPCN in NHs, and negatively impacting residents’ EOL quality. This may be related to the older age and lower educational level of the participants involved in this study, in keeping with the general situation of Chinese NAs. The difficulty in accepting and independently updating professional knowledge has become a shortcoming for NAs. This may also be due to the lack of HPCN training in China, where related knowledge has not yet been included in professional qualification training for NAs, consistent with the result that less than half of the involved NAs have been exposed to relevant knowledge.

There was a significant positive correlation between knowledge and attitudes, and knowledge was shown to be the strongest factor associated with attitudes, which has also been reported in other studies [32, 36]. The results indicate that better knowledge can help improve NHs’ attitudes towards HPCN. This may be explained by the construction of self-confidence through knowledge acquisition. Previous research demonstrated that NAs often lack confidence and feel uncomfortable in providing HPCN when they lack sufficient knowledge, which negatively influences their work performance, levels of work stress, ability to provide health guidance to residents, sensitivity to residents’ and families’ care needs, and their HPCN attitudes [36, 37].

HPCN attitudes were also associated with NAs’ marital statuses. NAs who were divorced or widowed reported better attitudes towards HPCN, differing from other studies that focused on practitioners and nurses and conducted in tertiary hospitals in China, which indicated that married medical staff had more positive attitudes [38, 39]. Being divorced or widowed is a significant trigger of empathy. Such experiences allow NAs to share the pain of the death of a loved one, creating a deep understanding of the HPCN, and is assumed to demystify the dying process and thereby reduce negative emotions. This matches the evidence that those who have already been exposed to death have more positive attitudes towards HPCN [40].

NAs from suburban NHs showed more positive attitudes towards HPCN than those from urban areas. This result has rarely been reported in previous studies. This may be related to the strong sense of community and mutual assistance in suburban communities, which helps develop harmonious communication and intimate emotional bonds through daily contact and caregiving. Our study revealed that there may be an opportunity to improve attitudes through better communication, highlighting the importance of excellent bedside communication skills with EOL residents.

Having HPCN training had a positive impact on attitudes, indicating that a lack of professional training in HPCN will inevitably affect NAs’ attitudes. Furthermore, we found that over 95.5% of NAs reported urgent training needs for HPCN, similar to previous studies in NH settings [3, 32]. Considering that NAs lack standardised training and learn exclusively by observing and imitating more experienced colleagues [41], this can be considered a reflection of NAs feeling intense support for EOL care issues, which was confirmed by international studies [42, 43]. NAs with higher training needs showed better attitudes regarding HPCN than those with lower training needs; those with higher training needs were more likely to believe in the benefits of HPCN for EOL residents and were thus more eager to acquire relevant knowledge that would allow them to provide quality HPCN.

Favourable attitude is considered the most significant enabler in providing high-quality HPCN services [38], which can be achieved through targeted training and practical experience [44]. In the context of the extensive pilot reforms of elderly care and HPCN in China, the construction of a theoretical and practical training system for NAs is still under exploration. Furthermore, there is still a lack of corresponding regulations regarding how to integrate the concept and practice of HPCN into the professional skill standards of NAs. Therefore, it is urgent to promote professional and targeted training tailored to their characteristics and acceptability based on their knowledge deficiency, moderate attitudes, and training needs, which can rationally and perceptually improve NAs’ HPCN attitudes. Additionally, the HPCN concept and related knowledge should be incorporated into the qualification training of NAs to help equip them with essential knowledge, full self-confidence, abundant first-hand experience, and excellent bedside communication skills for EOL residents.

Limitations

There were several limitations in our study. First, the data were drawn from a small purposive sample of participants, which may potentially introduce selection bias and limit the generalisability of our findings. Second, this is a cross-sectional study, showing only correlations but no causal relationship between attitudes towards HPCN and the factors mentioned above, so further longitudinal research is needed to evaluate these associations. Finally, based on the self-reported questionnaire, information bias may have occurred. Additionally, due to the limited length of the questionnaire, only a few influencing factors were conducted in this study. It is worthwhile to include factors like years of work experience, income, and physical conditions so as to find more effective ways to tailor targeted training programs.

Conclusions

In China, the government is trying to extend HPCN to NHs and strengthen multidisciplinary teams. This study found that NAs showed moderate attitudes towards HPCN, which improved as their knowledge score increased and training needs progressed. In addition, better HPCN attitudes were significantly associated with being divorced or widowed, training experience of HPCN, and suburban location. Integrated and continuous HPCN in NHs can be achieved only with the participation of positive and enabled NAs. Thus, there is an urgent need to scale up targeted training for NAs with different characteristics and incorporate concepts and knowledge of HPCN into professional qualification training to help improve their attitudes towards HPCN and equip them with essential knowledge and skills. The results of this study will help promote high-quality universal coverage of HPCN in NHs and enlighten other regions and countries with the same level of domestic and international development.

Data availability

All datasets during and/or analysed during this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HPCN:

-

Hospice and palliative care nursing

- NHs:

-

Nursing homes

- NAs:

-

Nursing assistants

- EOL:

-

End of life.

References

National Bureau of Statistics of China. Communiqué of the Seventh National Population Census (No. 5). 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/. Accessed 11 May, 2021.

Tark A, Estrada LV, Tresgallo ME, Quigley DD, Stone PW, Agarwal M. Palliative care and infection management at end of life in nursing homes: a descriptive survey. Palliat MED. 2020;34(5):580–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320902672

Park M, Yeom H, Yong SJ. Hospice care education needs of nursing home staff in South Korea: a cross-sectional study. BMC PALLIAT CARE. 2019;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-019-0405-x

National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Health Statistical Yearbook. Beijing: China Statistics Press; 2021.

Rodriquez J, Boerner K. Social and organizational practices that influence hospice utilization in nursing homes. J AGING STUD. 2018;46:76–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2018.06.004

Potrebny T, Igland J, Espehaug B, Ciliska D, Graverholt B. Individual and organizational features of a favorable work environment in nursing homes: a cross-sectional study. BMC HEALTH SERV RES. 2022;22(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08608-9

Karacsony S, Chang E, Johnson A, Good A, Edenborough M. Measuring nursing assistants’ knowledge, skills and attitudes in a palliative approach: a literature review. NURS EDUC TODAY. 2015;35(12):1232–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2015.05.008

Shen XF, Zhou LY. The effects of community-based preventive care on long-term care of city disabled elderly. Mod Nurse. 2020;27(07):75–7. https://doi.org/10.19792/j.cnki.1006-6411.2020.20.030

Miller SC, Lima JC, Intrator O, Martin E, Bull J, Hanson LC. Palliative Care consultations in nursing Homes and Reductions in Acute Care Use and potentially burdensome end-of-life transitions. J AM GERIATR SOC. 2016;64(11):2280–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14469

Kamal AH, Currow DC, Ritchie CS, Bull J, Abernethy AP. Community-based Palliative Care: the natural evolution for Palliative Care Delivery in the U.S. J PAIN SYMPTOM MANAG. 2013;46(2):254–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.07.018

Bui N, Halifax E, David D, Hunt L, Uy E, Ritchie C, Stephens C. Original Research: understanding nursing home staff attitudes toward death and dying: a Survey. AM J NURS. 2020;120(8):24–31. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000694336.19444.5a

Beck E, McIlfatrick S, Hasson F, Leavey G. Nursing home manager’s knowledge, attitudes and beliefs about advance care planning for people with dementia in long-term care settings: a cross-sectional survey. J CLIN NURS. 2017;26(17–18):2633–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13690

Unroe KT, Cagle JG, Dennis ME, Lane KA, Callahan CM, Miller SC. Hospice in the nursing home: perspectives of Front line nursing home staff. J AM MED DIR ASSOC. 2014;15(12):881–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.07.009

Oliver DP, Washington K, Kruse RL, Albright DL, Lewis A, Demiris G. Hospice Family Members’ perceptions of and experiences with end-of-Life Care in the nursing home. J AM MED DIR ASSOC. 2014;15(10):744–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.05.014

Esteban-Burgos AA, Lozano-Terrón MJ, Puente-Fernandez D, Hueso-Montoro C, Montoya-Juárez R, García-Caro MP. A New Approach to the identification of Palliative Care needs and Advanced Chronic patients among nursing home residents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(6):3171. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18063171

Aldridge MD, Hasselaar J, Garralda E, van der Eerden M, Stevenson D, McKendrick K, Centeno C, Meier DE. Education, implementation, and policy barriers to greater integration of palliative care: a literature review. Palliat MED. 2016;30(3):224–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216315606645

Sandvik RK, Selbaek G, Bergh S, Aarsland D, Husebo BS. Signs of imminent dying and change in Symptom Intensity during Pharmacological Treatment in dying nursing home patients: a prospective trajectory study. J AM MED DIR ASSOC. 2016;17(9):821–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2016.05.006

Estabrooks CA, Hoben M, Poss JW, Chamberlain SA, Thompson GN, Silvius JL, Norton PG. Dying in a nursing home: Treatable Symptom Burden and its link to modifiable features of work context. J AM MED DIR ASSOC. 2015;16(6):515–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2015.02.007

Shah S, Qaisar F, Azam I, Mansoor K. Perceptions, knowledge and attitudes towards the concept and approach of palliative care amongst caregivers: a cross-sectional survey in Karachi, Pakistan. BMC PALLIAT CARE. 2020;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00688-w

Sarre S, Maben J, Aldus C, Schneider J, Wharrad H, Nicholson C, Arthur A. The challenges of training, support and assessment of healthcare support workers: a qualitative study of experiences in three English acute hospitals. INT J NURS STUD. 2018;79:145–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2017.11.010

Lo RS, Kwan BH, Lau KP, Kwan CW, Lam LM, Woo J. The needs, current knowledge, and attitudes of care staff toward the implementation of palliative care in old age homes. AM J HOSP PALLIAT ME. 2010;27(4):266–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909109354993

Fryer S, Bellamy G, Morgan T, Gott M. Sometimes I’ve gone home feeling that my voice hasn’t been heard”: a focus group study exploring the views and experiences of health care assistants when caring for dying residents. BMC PALLIAT CARE. 2016;15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-016-0150-3

Liang LJ, Zhang GG. Study on the hospice care in chinese mainland. Practical Geriatr. 2018;32(1):20–2. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1003-9198.2018.01.007

WANG Yan, JIA Tongying, YUAN Huiyun. International comparison of the nursing assistants industry. Chin Hosp. 2016;20(11):76–8.

Feng Yansen, Shen Jun, Ren Liu. Effect of cognitive reappraisal group counseling on anxiety and depression of nursing assistants caring for the disabled elderly in nursing homes. J Nurs Sci. 2018;33(01):79–82. https://doi.org/10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2018.01.079

Achora S, Labrague LJ. An integrative review on knowledge and attitudes of nurses toward Palliative Care. J HOSP PALLIAT NURS. 2019;21(1):29–37. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000481

Sekse RJT, Hunskår I, Ellingsen S. The nurse’s role in palliative care: a qualitative meta-synthesis. J CLIN NURS. 2018;27(1–2):e21–e38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13912

Shu Z, Wang Y, Li T, Jing L, Sun X. Instrument development of health providers’ knowledge, attitude and practice of Hospice Care Scale in China. Int J Health Plann Manag. 2021;36(2):364–80. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3074

Li-mei JING, Tian-tina LI, Zhi-qun SHU, et al. Study on the volunteers’ knowledge, attitude, behavior and training needs of Hospice Care. Med Philos. 2020;41(21):30–4. https://doi.org/10.12014/j.issn.1002-0772.2020.21.07

Frommelt KH. Attitudes toward care of the terminally ill: an educational intervention. AM J HOSP PALLIAT ME. 2003;20(1):13–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/104990910302000108

Liu W, Hu W, Chiu Y, Chiu T, Lue B, Chen C, Wakai S. Factors that influence physicians in providing palliative care in rural communities in Taiwan. SUPPORT CARE CANCER. 2005;13(10):781–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-005-0778-7

Chen IH, Lin KY, Hu SH, Chuang YH, Long CO, Chang CC, Liu MF. Palliative care for advanced dementia: knowledge and attitudes of long-term care staff. J CLIN NURS. 2018;27(3–4):848–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14132

Leclerc B, Lessard S, Bechennec C, Le Gal E, Benoit S, Bellerose L. Attitudes toward death, dying, end-of-life Palliative Care, and Interdisciplinary Practice in Long Term Care Workers. J AM MED DIR ASSOC. 2014;15(3):207–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2013.11.017

Xiaohan T, Limei J, Zhiqun S, et al. Survey on attitude and influencing factors of hospice care among health providers in Shanghai. Chin J Gen Pract. 2021;20(05):556–61. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn114798-20200815-00909

Jones C, Moyle W, Stockwell-Smith G. Caring for older people with dementia: an exploratory study of staff knowledge and perception of training in three australian dementia care facilities. AUSTRALAS J AGEING. 2013;32(1):52–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6612.2012.00640.x

Kim S, Lee K, Kim S. Knowledge, attitude, confidence, and educational needs of palliative care in nurses caring for non-cancer patients: a cross-sectional, descriptive study. BMC PALLIAT CARE. 2020;19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-00581-6

LH Su, ML Huang, YL Lin, et al. Knowledge and attitudes of clinical nurses regarding end-of-life care: survey in a regional hospital in central. Taiwan J Hospice Palliat Care 2008(13):431–46.

Chu T, Zhang H, Xu Y, Teng X, Jing L. Predicting the behavioral intentions of hospice and palliative care providers from real-world data using supervised learning: a cross-sectional survey study. FRONT PUBLIC HEALTH. 2022;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.927874

LI Fangfang. Study on attitude toward hospice care and its influencing factors in medical staff. Chin Evidence-based Nurs. 2019;5(10):890–8. https://doi.org/10.12102/j.issn.2095-8668.2019.10.006

Arslan D, Akca NK, Simsek N, Zorba P. Student Nurses’ Attitudes toward dying patients in Central Anatolia. INT J NURS KNOWL. 2014;25(3):183–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/2047-3095.12042

Goller M, Steffen B, Harteis C. Becoming a nurse aide: an investigation of an existing Workplace Curriculum in a nursing home. VOCAT LEARN. 2019;12(1):67–85. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12186-018-9209-z

Beck I, Tornquist A, Brostrom L, Edberg AK. Having to focus on doing rather than being-nurse assistants’ experience of palliative care in municipal residential care settings. INT J NURS STUD. 2012;49(4):455–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.10.016

Bekkema N, de Veer AJE, Albers G, Hertogh CMPM, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Francke AL. Training needs of nurses and social workers in the end-of-life care for people with intellectual disabilities: a national survey. NURS EDUC TODAY. 2014;34(4):494–500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2013.07.018

Teng X, Tang M, Jing L, Xu Y, Shu Z. Healthcare Provider Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices in Hospice Care and their influencing factors: a crosssectional study in Shanghai. Int J Health Policy Manage. 2022. https://doi.org/10.34172/ijhpm.2022.6525

Acknowledgements

First, we gratefully acknowledge the participation of the nursing homes and providers. Second, we appreciate the support of grants from the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality, Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai [22ZR1461400], the Soft Science Research Project of Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan by Shanghai Science and Technology Commission [23692112700], the Humanities and Social Science Research Planning Fund of the Ministry of Education [20YJAZH045], the Humanities and Social Sciences planning from Shanghai Plan of Philosophy and Social Science [2019BGL032], and the Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine [202110268052]. Third, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing. Finally, we would like to thank the participants who agreed to participate voluntarily in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shanghai Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality, Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (grant number:22ZR1461400), Soft Science Research Project of Science and Technology Innovation Action Plan by Shanghai Science and Technology Commission (grant number:23692112700), Ministry of Education, Humanities and Social Sciences Planning (grant number:20YJAZH045), Shanghai Plan of Philosophy and Social Science (grant number:2019BGL032), and Shanghai University of Traditional Chinese Medicine (grant number:202110268052).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZY, YX, and LJ conceived of and designed the study. LJ contacted with organisation and designed the questionnaire. ZY, HZ, HC, JY, RZ, JW, and HZ carried out the data collection. ZY, HZ, HC, and JY analysed the data. TC provided guidance for data analysis. ZY and HZ drafted the manuscript. ZY, LJ, YQ and HZ reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Shanghai Ninth People’s Hospital (ref: SH9H-2021-T11-1). All methods used in this study were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and relevant guidelines and regulations. All nursing assistants participated voluntarily. Written informed consents were obtained anonymously from all participants before they completed the questionnaires.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Z., Jing, L., Zhang, H. et al. Attitudes and influencing factors of nursing assistants towards hospice and palliative care nursing in chinese nursing homes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Palliat Care 22, 49 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01175-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-023-01175-8