Abstract

Background

Spirituality is particularly important for patients suffering from life-threatening illness. Despite research showing the benefits of spiritual assessment and care for terminally ill patients, their spiritual needs are rarely addressed in clinical practice. This study examined the factor structure and reliability of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual (FACIT-Sp) in patients with advanced cancer. It also examined the clinical meaning and reference intervals of FACIT-Sp scores in cancer patients subgroups through a literature review.

Methods

A forward-backward translation procedure was adopted to develop the Italian version of the FACIT-Sp, which was administered to 150 terminally ill cancer patients. Exploratory factor analysis was used for construct validity, while Cronbach’s α was used to assess the reliability of the scale.

Results

This study replicates previous findings indicating that the FACIT-Sp distinguish well between features of meaning, peace, and faith. In addition, the internal consistency of the FACIT-Sp was acceptable. The literature review also showed that terminal cancer patients have the lowest scores on the Faith and Meaning subscales, whereas cancer survivors have the highest scores on Faith.

Conclusions

The Italian version of the FACIT-Sp has good construct validity and acceptable reliability. Therefore, it can be used as a tool to assess spiritual well-being in Italian terminally ill cancer patients. This study provides reference intervals of FACIT-Sp scores in newly diagnosed cancer patients, cancer survivors, and terminally ill cancer patients and further highlights the clinical meaning of such detailed assessment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Background

Previous research has yielded supportive evidence on the positive influence of spiritual well-being in health care, especially in the context of a serious and life-limiting illness such as cancer [1]. It was shown to promote better psychosocial adjustment to cancer [2, 3] and cancer-related growth [4, 5]. There is a growing incidence of cancer worldwide that poses a considerable threat to quality of life and public health [6]. Therefore, it is essential to pay attention to patients’ spiritual needs [7]. Despite research showing the benefits of spiritual assessment and care for cancer patients, their spiritual needs are not supported by the medical system [8].

Spirituality may provide “a context in which people can make sense of their lives, and feel whole, hopeful and peaceful even in the midst of life’s most serious challenges” [9]. A more recent definition by Visser, Garssen and Vingerhoets [10] states that spirituality refers to “one’s striving for and experience of a connection with the essence of life of which the experiences of meaning in life and connectedness are central elements”. Spirituality is particularly relevant for patients suffering from life-threatening illness, especially at the end of life [11]. Indeed, these patients may struggle with questions about mortality or the meaning of life that they had not considered before they became ill. Although some patients may turn to religion to meet their existential needs, others find relief through non-religious spiritual beliefs.

According to the Biopsychosocial-Spiritual Model [12], spirituality is positively associated with Quality of Life (QOL) [9, 13, 14]. When spiritual needs are substantially unmet, end of life patients are forced to grapple with an overall burden of daily distress and worries that affect their emotional and spiritual well-being [15] as well as health care decision-making [8, 16, 17]. Nowadays, spirituality is recognized by palliative care specialists as an important strategy to cope with life-threatening illness.

An increasing number of researchers have investigated and included the assessment of spirituality in health care [18, 19]. Spiritual well-being is a component of spirituality [20] that can be defined as “a sense of meaning in life, harmony, peacefulness, and a sense of drawing strength and comfort from one’s faith” [21]. Perception of meaning in life refers to a sense of understanding, significance, and purpose in life [22]. Peace includes a sense of being reconciled to one’s adverse life circumstances [3]. Finally, faith is a sense of comfort or strength one derives from one’s faith and spiritual beliefs [23].

One of the most widely used instruments for measuring spiritual well-being in patients with chronic and/or life-threatening diseases is the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual (FACIT-Sp) [23]. It was originally validated in USA with cancer and HIV/AIDS patients, demonstrating good psychometric properties [23]. A principal components analysis on the 12 items of the FACIT-Sp revealed two distinct factors that were related to Meaning/Peace and Faith. Given that meaning suggests a cognitive aspect of spirituality and peace an affective component, Canada and colleagues [21] used confirmatory factor analysis to compare the original two-factor model with the three-factor solution. The study of Canada and colleagues [21] supported a three-factor solution of the FACIT-Sp (Meaning, Peace, and Faith), which represented an improvement over the original version and also enabled a more detailed analysis of the contribution of different facets of spirituality on QOL. The clinical meaningfulness of the three-factor model was subsequently confirmed [3, 24]. Although it was mainly used in oncologic settings, the original instrument has been used also with different populations and settings [25,26,27,28,29].

To our knowledge, only one study [24] was conducted to examine the factorial validity of the FACIT-Sp with advanced cancer patients. However, these patients were newly diagnosed with advanced cancer. No previous study has investigated the factorial validity of FACIT-Sp in patients with advanced and terminally ill cancer who were also no newly diagnosed.

The aim of this study was twofold. First, to culturally adapt the Italian version of the FACIT-Sp in a sample of cancer patients and to examine its acceptability, factorial validity, and reliability. Second, to examine and interpret the clinical meaning of FACIT-Sp scores through a literature review of published articles and to define reference intervals for FACIT-Sp scores in cancer patients subgroups. Such reference intervals can be helpful to interpret the distribution of the related scores in the cited patients subgroups from a statistical perspective, laying the groundwork for further investigations to better clarify their clinical meaning.

Methods

Study design and procedure

This study is a secondary analysis of the Palliative Care Outcome Scale (POS) Italian validation study [30]. We also conducted a literature review to examine and interpret the clinical meaning of FACIT-Sp scores and to define reference intervals for FACIT-Sp scores for newly diagnosed cancer patients, cancer survivors, and terminal cancer patients.

The palliative care teams comprised of doctors, nurses, and psychologists who administered the questionnaires during staff meetings. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants before data collection, after being informed about the voluntary nature of participation, and the right to withdraw from the study at any moment. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the National Institute for Cancer Research of Genoa (Deliberation EC07.001 of 19 February 2007).

Participants

The study was conducted with a sample of 150 advanced and terminally ill cancer patients attending various palliative care services (hospices or home care). Eligible patients had a diagnosis of cancer, were 18 years of age or more, and gave their consent to participate in the study.

Measures

The English original version of the FACIT-Sp, officially provided by the FACIT.org group (www.facit.org), was translated into Italian using a forward-backward translation method to establish cross-language equivalence. The instrument includes 12 items that measure aspects of spiritual well-being related to meaning and purpose in life, peacefulness, and a sense of strength and comfort one derives from one’s faith and spiritual beliefs. Participants were required to indicate how true each statement was for them during the previous week on a 5-point scale, ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much). Higher scores indicate higher levels of spiritual well-being. This instrument takes around 5–10 min to complete. We used the ECOG Performance Status to measure how cancer impacts patients’ daily living abilities [31].

Statistical analysis

We assessed the acceptability of the instrument to respondents through compliance (% of patients who completed the questionnaire) and adherence (% of patients who completed each item). We assumed that 5–10% was an acceptable proportion of missing for each item of the questionnaire, taking into account the settings where the FACIT-Sp was administered. The relationship between FACIT-Sp subscales and total scores and socio-demographic variables was evaluated using Pearson’s r and Spearman’s rho, whereas the internal consistency was assessed by Cronbach’s α. We also calculated Spearman’s rho of FACIT-Sp subscales and total scores with ECOG index. We used t-test to compare the FACIT-sp total scores between males and females.

For inclusion in the review, we considered all papers that reported mean and standard deviation for the FACIT-Sp scores. To define the lower and upper limits of the reference intervals for the FACIT-Sp scores, we classified all papers into three categories according to the patients’ characteristics:

-

1)

newly diagnosed cancer patients;

-

2)

cancer survivors;

-

3)

terminal cancer patients.

The selection of categories was guided by the expectation that reference intervals would be different according to these patients’ characteristics. For each FACIT-Sp score we calculated weighted means and weighted standard deviations, where the weights are determined by the number of patients. To define the reference intervals, we assumed a normal distribution of scores, then we used the 2.5th percentile as the lower limit and the 97.5th percentile as the upper one.

Literature review

An electronic search using Embase, Medline, Cochrane Library, Cinahl and Psycinfo from 2002 to June 2016 was performed to identify the literature on the FACIT-Sp scale. The search terms used were Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual, FACIT-Sp, FACIT, and the search limits used were adults (from 18 years), English, French, Italian, and Spanish languages. The inclusion criteria for the review were published studies with cancer patients in all stages of disease containing FACIT-Sp scores. Unpublished studies or proceedings from conferences were excluded from the review.

Results

Acceptability of the instrument and disease characteristics

One hundred thirty-six of the 150 patients completed the FACIT-Sp, with a compliance of 90.6%. The adherence to the instrument was high, with a range from 92% (item 12) to 100% (item 1 and 7).

Ninety-five per cent of patients had a solid cancer, of which most had gastrointestinal cancer (41.2%). The majority of patients had a performance status of 3 (limited self-care) or 4 (completely disabled). Additional demographic information and disease-related characteristics of the patients are provided in Table 1.

Demographic and psychological variables

There were no differences between males and females in terms of FACIT-Sp total score (Males: M = 22.83 ± 7.05, Females: M = 22.86 ± 7.01, t(130) = − 0.025, p = .980). Moreover, the FACIT-Sp total score was not correlated with age (r = −.11), education (rho Spearman = .03), marital status (rho Spearman = .03), cancer type (rho Spearman = −.04), and the ECOG (rho Spearman = −.13).

Exploratory factor analysis

We used an exploratory factor analysis with principal axis factoring extraction to examine the structure of the FACIT-Sp. The number of factors was determined by a parallel analysis using the SPSS syntax [32]. This criterion suggested a three-factor solution (eigenvalues 2.8, 3.0, 2.7), accounting for 55% of the variance. Previous research suggests that the scales are correlated [21]. Thus, we applied an oblimin rotation to this solution. Correlations among factors were similar to those in previous research, with Meaning and Peace factors correlating at .43, and Meaning and Faith as well as Peace and Faith correlating at .28. The first factor (34% of total variance) was defined by five items reflecting meaning; the second factor (13% of total variance) was defined by three items referring to faith; finally, the third factor (8% of total variance) was defined by four items reflecting peace. Each item loaded on only one of the three factors with a value greater than 0.40 (see Table 2). All but one of the four items that make up the Faith scale loaded on this factor. The one item on the Faith scale (“I know that whatever happens with my illness, things will be okay”) that did not load on this factor had a .55 loading on the Meaning scale. Table 2 reports the factor loadings of FACIT-Sp Scale items (the allocation of items to subscales according to different validation studies is provided in Table S1).

Reliability

Internal consistency was adequate with Cronbach’s α of .73, .79, and .85 for the Meaning, Peace, and Faith subscales, respectively. Cronbach’s α for the Total scale was .79. Mean inter-item correlation was .54. Table 3 reports means, standard deviations and reliabilities for FACIT-Sp scores.

Literature review

The literature review yielded 44 studies. Of these, 22 were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria. Finally, 22 articles were included in the review (see Fig. 1).

The 22 articles that are included in the review are summarized in Table S2.

Reference intervals

Papers were classified according to the following categories:

- 1)

- 2)

- 3)

Terminal cancer patients had the lowest scores on the Faith and Meaning dimensions, whereas cancer survivors had the highest score on the Faith dimension. Newly diagnosed cancer patients and cancer survivors had similar and the highest scores on the Meaning dimension, whereas the latter had the highest score on the Peace dimension. Table 4 reports the lower and upper limits for reference intervals.

Discussion

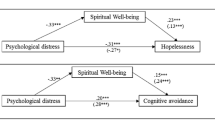

Exploratory factor analysis confirmed the three-factor structure of the FACIT-Sp found in previous research [3, 21, 38, 43]. Indeed, different from the original two-factor solution [23], this structure reflects the conceptual difference between meaning and peace: the first reflecting a cognitive dimension, and the latter an affective dimension of religious and spiritual well-being [21, 38]. However, different from previous studies in which item 12 (“I know that whatever happens with my illness, things will be okay”) was located in the Peace factor [21, 43], in our study it was found to be located in the Meaning factor. Other studies [38, 44] have found a double loading of the item 12 on both Peace and Faith factors. The different factor loading for this item may reflect cultural differences; patients in our sample may have relied on meaning, rather than on peace or faith, as a coping mechanism used to make sense of their life despite the illness. Consistent with previous studies, Faith was moderately correlated with both meaning and peace, whereas the association between peace and meaning was medium to large.

In our review of studies using the FACIT-Sp, terminal cancer patients had the lowest scores on most subscales of the FACIT-Sp, indicating greater impairment in the spiritual well-being dimensions. This result seems somewhat unexpected, given that previous studies showed that awareness of terminal illness was associated with better spiritual well-being in terminal cancer patients [45]. However, comparisons with Leung et al.’s [45] findings are difficult because they used a different questionnaire to assess spiritual well-being. Moreover, we do not know if terminal cancer patients included in our review were aware of their cancer diagnosis and prognosis. Indeed, prognosis of a terminally ill condition is frequently not disclosed to maintain hope for patients and their families.

This study has some limitations. First, we collected data using a convenience sampling method. Therefore our results cannot be generalized to all cancer patients in Italy. Further studies with random sampling procedures are needed. Second, an examination of the FACIT-Sp concurrent validity is needed by using well-validated measures of spiritual well-being. Third, only advanced and terminally ill cancer patients took part in the study. Therefore, the generalization of our findings to different cancer patients requires caution. Further studies with different types of clinical groups (e.g., newly diagnosed cancer patients and cancer survivors) are needed to cross-validate our findings. The use of a multi-sample confirmatory factor analysis might be a useful approach [46]. Notwithstanding these limitations, this is the first study that examined the factorial validity of the FACIT-Sp with patients with advanced and terminally ill cancer who were also no newly diagnosed.

Conclusions

There is a growing incidence of cancer worldwide [6], and meeting the spiritual needs of patients is a vital aspect of care [1]. Patients with serious illness and end-of-life issues have the desire to include spirituality in their care [18]. Indeed, spirituality can be an inner resource in helping patients find a new meaning in their existence by reevaluating their experience of illness, and recognize what ultimately matters most to them [11]. It is therefore essential that clinicians address regular assessment of patients’ spiritual issues, treat spiritual distress and promote a sense of meaning in life, purpose, and peacefulness as parts of a biopsychosocial-spiritual approach to end-of-life care.

The results of the present study confirmed the three-factor structure of the FACIT-Sp also in an Italian sample of terminally ill cancer patients who were also no newly diagnosed. To our knowledge, no previous studies have examined the psychometric properties of this instrument with these patients. Therefore, the FACIT-Sp is a valid and reliable instrument to measure spiritual well-being in these patients and to identify their spiritual strengths that may be essential for a person-centered care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

- FACIT-Sp:

-

Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy-Spiritual

- POS:

-

Palliative Care Outcome Scale

- QOL:

-

Quality of Life

References

# indicate studies included in Table S1 and * indicate studies included in Table S2.

Chen J, Lin Y, Yan J, et al. The effects of spiritual care on quality of life and spiritual well-being among patients with terminal illness: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2018;32:1167–79.

Park CL, Cho D. Spiritual well-being and spiritual distress predict adjustment in adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2017;26:1293–300.

*Whitford HS, Olver IN. The multidimensionality of spiritual wellbeing: peace, meaning, and faith and their association with quality of life and coping in oncology. Psychooncology. 2012;21:602–10.

Paredes AC, Pereira MG. Spirituality, distress and posttraumatic growth in breast cancer patients. J Relig Health. 2018;57:1606–17.

Yanez B, Edmondson D, Stanton AL, et al. Facets of spirituality as predictors of adjustment to cancer: relative contributions of having faith and finding meaning. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:730–41.

Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:524–48.

Mesquita AC, Chaves ÉDCL, Barros GAMD. Spiritual needs of patients with cancer in palliative care: an integrative review. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2017;11:334–40.

Balboni TA, Vanderwerker LC, Block SD, et al. Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:555–60.

Brady MJ, Peterman AH, Fitchett G, et al. A case for including spirituality in quality of life measurement in oncology. Psychooncology. 1999;8:417–28.

Visser A, Garssen B, Vingerhoets A. Spirituality and well-being in cancer patients: a review. Psychooncology. 2010;19:565–72.

Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl_3):49–55.

Sulmasy DP. A biopsychosocial-spiritual model for the care of patients at the end of life. Gerontologist. 2002;42(Suppl 3):24–33.

Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:445–52.

Czekierda K, Banik A, Park CL, et al. Meaning in life and physical health: systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Psychol Rev. 2017;11:387–418.

Pearce MJ, Coan AD, Herndon JE II, et al. Unmet spiritual care needs impact emotional and spiritual well being in advanced cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2012;20:2269–76.

Pesut B. Incorporating patients’ spirituality into care using Gadow’s ethical framework. Nurs Ethics. 2009;16:418–28.

Phelps AC, Maciejewski PK, Nilsson M, et al. Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. JAMA. 2009;301:1140–7.

Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:885–904.

Steinhauser KE, Fitchett G, Handzo GF, et al. State of the science of spirituality and palliative care research part I: definitions, measurement, and outcomes. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2017;54:428–40.

Monod S, Brennan M, Rochat E, et al. Instruments measuring spirituality in clinical research: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1345–57.

#Canada AL, Murphy PE, Fitchett G, et al. A 3-factor model for the FACIT-Sp. Psychooncology. 2008;17:908–16.

Park CL, Gutierrez IA. Global and situational meanings in the context of trauma: relations with psychological well-being. Couns Psychol Q. 2013;26:8–25.

#*Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, et al. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. 2002;24:49–58.

#*Bai M, Dixon J. Exploratory Factor Analysis of the 12-Item Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy and Spiritual Well-Being Scale in People Newly Diagnosed With Advanced Cancer. J Nurs Meas. 2014;22:404–20.

Ando M, Morita T, Ahn SH, et al. International comparison study on the primary concerns of terminally ill cancer patients in short-term life review interviews among Japanese, Koreans, and Americans. Palliat Support Care. 2009;7:349–55.

Desbiens JF, Fillion L. Coping strategies, emotional outcomes and spiritual quality of life in palliative care nurses. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2007;13:291–300.

Iani L, Lauriola M, Angeramo AR, et al. Sense of meaning influences mental functioning in chronic renal patients. J Health Psychol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318781908.

Iani L, Quinto RM, Porcelli P, et al. Psychological resources in individuals with skin diseases: The role of sense of coherence and positivity in spiritual well-being and distress. Manuscript submitted for publication. 2020.

Smeets R, Noah EM, Seiferth NY, et al. Bioelectric impedance analysis and quality of life after body-contouring procedures in plastic surgery. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:940–5.

Costantini M, Rabitti E, Beccaro M, et al. Validity, reliability and responsiveness to change of the Italian palliative care outcome scale: a multicenter study of advanced cancer patients. BMC Palliat Care. 2016;15:23.

Oken M, Creech R, Tormey D, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the eastern cooperative oncology group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–55.

O’Connor BP. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2000;32:396–402.

*Bai M, Dixon J, Williams A, et al. Exploring the individual patterns of spiritual well-being in people newly diagnosed with advanced cancer: a cluster analysis. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:2765–73.

*Jafari N, Farajzadegan Z, Zamani A, et al. Spiritual well-being and quality of life in Iranian women with breast cancer undergoing radiation therapy. Support Care Cancer. 2013a;21:1219–25.

*Canada AL, Fitchett G, Murphy PE, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in spiritual well-being among cancer survivors. J Behav Med. 2013;36:441–53.

*Canada AL, Murphy PE, Fitchett G, et al. Re-examining the contributions of faith, meaning, and peace to quality of life: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors-II (SCS-II). Ann Behav Med. 2016;50:79–86.

*Munoz AR, Salsman JM, Stein KD, et al. Reference values of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-spiritual well-being: a report from the American Cancer Society’s studies of cancer survivors. Cancer. 2015;121:1838–44.

#*Murphy PE, Canada AL, Fitchett G, et al. An examination of the 3-factor model and structural invariance across racial/ethnic groups for the FACIT-Sp: a report from the American Cancer Society's Study of Cancer Survivors-II (SCS-II). Psychooncology. 2010;19:264–72.

*Ando M, Morita T, Okamoto T, et al. One-week short-term life review interview can improve spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. Psychooncology. 2008;17:885–90.

*Ando M, Morita T, Akechi T, et al. Efficacy of short-term life-review interviews on the spiritual well-being of terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;39:993–1002.

*Bovero A, Leombruni P, Miniotti M, et al. Spirituality, quality of life, psychological adjustment in terminal cancer patients in hospice. Eur J Cancer Care. 2016;25:961–9.

*Wang YC, Lin CC. Spiritual well-being may reduce the negative impacts of cancer symptoms on the quality of life and the desire for hastened death in terminally ill cancer patients. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:E43–50.

#Lazenby M, Khatib J, Al-Khair F, et al. Psychometric properties of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy—spiritual Well-being (FACIT-Sp) in an Arabic-speaking, predominantly Muslim population. Psychooncology. 2013;22:220–7.

#Haugan G. The FACIT-Sp spiritual well-being scale: an investigation of the dimensionality, reliability and construct validity in a cognitively intact nursing home population. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29:152–64.

Leung KK, Chiu TY, Chen CY. The influence of awareness of terminal condition on spiritual well being in terminal cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2006;31:449–55.

Iani L, Barbaranelli C, Lombardo C. Cross-validation of the reduced version of the food craving questionnaire-trait using confirmatory factor analysis. Front Psychol. 2015;6:433.

#Noguchi W, Ohno T, Morita S, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Spiritual (FACIT–Sp) for Japanese patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:240–5.

#*Jafari N, Zamani A, Lazenby M, et al. Translation and validation of the Persian version of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy-Spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-Sp) among Muslim Iranians in treatment for cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2013b;11:29–35.

#Agli O, Bailly N, Ferrand C. Validation of the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy—spiritual well-being (FACIT-Sp12) on French old people. J Relig Health. 2017;56:464–76.

#Aktürk Ü, Erci B, Araz M. Functional evaluation of treatment of chronic disease: Validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the Spiritual Well-Being Scale. Palliat Support Care. 2017;15:684–92.

*Schubart JR, Wise J, Deshaies I, et al. Quality of life assessment in postoperative patients with upper GI malignancies. J Surg Res. 2010;163:40–6.

*Cook EL, Silverman MJ. Effects of music therapy on spirituality with patients on a medical oncology/hematology unit: a mixed-methods approach. Arts Psychother. 2013;40:239–44.

*Piderman KM, Johnson ME, Frost MH, et al. Spiritual quality of life in advanced cancer patients receiving radiation therapy. Psychooncology. 2014;23:216–21.

*Sun V, Kim JY, Irish TL, et al. Palliative care and spiritual well-being in lung cancer patients and family caregivers. Psychooncology. 2015;25:1448–55.

*Gonzalez P, Castañeda SF, Dale J, et al. Spiritual well-being and depressive symptoms among cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2014;22:2393–400.

*Lazenby M, Khatib J. Associations among patient characteristics, health-related quality of life, and spiritual well-being among Arab Muslim cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2012;15:1321–4.

*Rodin G, Zimmermann C, Rydall A, et al. The desire for hastened death in patients with metastatic cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33:661–75.

*Wittmann M, Vollmer T, Schweiger C, et al. The relation between the experience of time and psychological distress in patients with hematological malignancies. Palliat Support Care. 2006;4:357–63.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.C., L.I. and S.C. made a substantial contribution to the concept and design of the work, they analysed and interpreted data. E.R. drafted the article; S.O. and F.D.V. revised the article and approved the version to be published. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the National Institute for Cancer Research of Genoa (Deliberation EC07.001 of 19 February 2007). All participants provided signed informed consent to participate.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rabitti, E., Cavuto, S., Iani, L. et al. The assessment of spiritual well-being in cancer patients with advanced disease: which are its meaningful dimensions?. BMC Palliat Care 19, 26 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-0534-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-020-0534-2