Abstract

Background

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an autoimmune blistering disease (AIBD). Some reports suggest that it has a drug-related pathogenesis especially anti-hypertensive drug.

Case presentation

A 67-year-old man with a 7-year history of essential hypertension was prescribed enalapril maleate for 5 months. He presented at our department with pain, ulcers, and blisters on the oral mucosa. We performed clinical, histopathology, and direct immunofluorescence examinations, and findings were consistent with the diagnostic criteria for MMP. Consequently, we consulted with the cardiovascular physician and agreed to discontinue the enalapril maleate replacing it with irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide tablets and topical corticosteroid therapies instead. The lesions healed without recurrence.

Conclusions

ABID induced by antihypertensive drugs have been reported, and enalapril maleate has been implicated as an antihypertensive agent that may trigger AIBDs, such as MMP. This case highlights the potential relationship between antihypertensive drugs and MMP, of which clinicians should be aware to accurately diagnose and promptly relieve patients’ pain.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

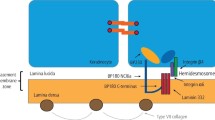

Mucous membrane pemphigoid (MMP) is an immune-mediated, vesiculobullous disease, characterised by mucosal subepithelial or subepidermal blistering primarily in the oral mucosa and conjunctiva [1, 2]. As one of several subepithelial blistering diseases, autoantibodies are directed against structural proteins of the hemidesmosome in the basement membrane zone [1,2,3,4]. The main target in MMP is structural protein BP180 (or type XVII collagen) [5]. However, the mechanisms underlying its pathogenesis have not been elucidated [5]. Some reports indicate that medications trigger MMP, such as antirheumatic drugs, clonidine (a central antihypertensive drug), and practolol (for treating angina pectoris) [6]. Recently, an emerging drug class of anti-programmed death-1 antibodies has been increasingly associated with MMP [7, 8]. The diagnosis of MMP is based on clinical examination, medical history, histopathologic analysis and serology [9], in which direct immunofluorescence (DIF) is the cornerstone diagnostic procedure [10].

Routine histology reveals subepithelial split with mixed inflammatory infiltration of eosinophils and neutrophils [11]. DIF reveals linear immunoglobin (Ig) A, IgG, or C3 along the basement membrane zone [11]. DIF serves as the most accurate diagnostic test for MMP, with a sensitivity between 60% and 90% [12]. If there is a concern for a false negative DIF and high clinical suspicion of MMP, repeat biopsies may be warranted. Based on current diagnostic guidelines, repeat biopsies for DIF increase sensitivity from 70–95% [12]. Indirect immunofluorescence microscopy may also be used for diagnosis [3, 13]. Autoantibodies against BP180 and BP230 may be detected via enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) testing [9].

Case presentation

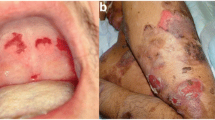

A 67-year-old man presented to our department with pain, ulcers, and blisters in the oral mucosa for 3 months. The patient had no specific disease or familial medical history, except for a history of essential hypertension for 7 years and kidney stones for 5 years. The patient had been taking enalapril maleate for 5 months. Oral examination revealed full mouth edentulism. The alveolar ridge, suboral, and vestibular sulcus mucosae exhibited generalized erythema and desquamation, and there were multiple large ulcers covered with yellowish slough tissue and blisters (Fig. 1a, b). No other cutaneous or mucosal sites were involved, such as the conjunctiva or genital or nasopharyngeal mucosae.

The clinical manifestations of a 67-year-old man presenting with oral mucosa pain, ulcers, and blisters. (a, b) The clinical findings at the patient’s first visit. The alveolar ridge mucosa and vestibular sulcus mucosa showed generalized erythema, desquamation, multiple large ulcers covered with yellowish slough tissue, and multiple blisters. (c, d) The clinical findings at the patient’s final visit. Most erosions resolved after discontinuing the enalapril maleate. Erosions on the alveolar ridge mucosa and the vestibular sulcus mucosa remained but were healing

We biopsied the patient’s alveolar ridge mucosal erosion lesions and nearby normal mucosa tissue. Histopathological examination revealed local atrophy of the mucosal epithelium, subepithelial blister formation, plasma cell and lymphocyte infiltration into the lamina propria, lymphoid follicle formation, capillary proliferation, and dense neutrophil infiltration in the focal area (Fig. 2a, b). DIF revealed a linear deposition of IgG and IgA along the basement membrane (Fig. 2c, d). BP180-NC16A, desmoglein (DSG) 1, and DSG 3 ELISA did not detect circulating autoantibodies. Therefore, we diagnosed the patient with MMP based on these combined results.

A supplementary examination of a biopsy sample from the patient’s alveolar ridge mucosal erosion lesions. (a, b) Light microscopy images of a biopsy specimen of the alveolar ridge mucosa showing subepithelial blister formation, plasma cell and lymphocyte infiltration in the lamina propria, lymphoid follicle formation, capillary proliferation, and dense neutrophil infiltration in the focal area (hematoxylin and eosin staining, original magnification ×10). Direct immunofluorescence microscopy images show linear (c) immunoglobin (Ig) G and (d) IgA deposits along the epithelial basement membrane zone

Firstly, we administered topical corticosteroid therapies (Apply locally after diluting 0.5% dexamethasone at a 1:10 ratio, and locally seal after diluting 0.5% betamethasone at a 1:1 ratio), but it was ineffective, and the lesions recurred during treatment. We identified other cases of MMP caused by antihypertensive drugs in the literature [14] and speculated that enalapril maleate might be a trigger for AIBD due to its short-term use. Then, we consulted with the cardiovascular physician and agreed to discontinue enalapril maleate for three weeks, replacing it with irbesartan/hydrochlorothiazide tablets. Simultaneous topical corticosteroid therapies (Apply 0.1% triamcinolone acetonide oral paste locally, seal locally after diluting 0.5% betamethasone at a 1:1 ratio) gradually healed the oral mucosa erosion and blisters (Fig. 1c, d). The patient’s oral lesions had not recurred at the most recent follow-up (11 months).

Discussion

Enalapril maleate is an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor commonly used to treat essential hypertension, stable chronic heart failure, myocardial infarction, and diabetic nephropathy [15, 16]. Enalapril maleate can also cause angioedema [17] and is a suspected trigger of autoimmune blistering diseases (AIBDs) of the skin and mucosa, such as pemphigus [18] and bullous pemphigoid (BP) [19]. A report described a patient who used enalapril maleate for 6 months for primary pulmonary hypertension and arrhythmia, presented with a large area of pustular lesions and erythema on the face and back. Histopathology and DIF confirmed pemphigus vegetans, and the patient was treated with prednisone. Furthermore, the lesions gradually disappeared over 1 month after discontinuing enalapril maleate [20].

Our second treatment attempt discontinued the use of enalapril maleate, a potential MMP inducing factor. The patient’s lesions gradually healed with no sign of recurrence, further supporting that enalapril maleate triggers MMP. There is no literature regarding the relationship between enalapril maleate and MMP, and the specific pathogenesis is unclear. BP is one of the most common AIBDs, characterized by autoantibody production against hemidesmosomal proteins of the skin and mucosa, mainly affecting older adults [21]. Drug-induced bullous pemphigoid is common, and here we have summarized the relevant case reports of drug-related bullous pemphigoid in the past five years (Table 1) [22,23,24,25,26].

To address this issue, Stavropoulos [27] proposed four possible pathogenetic mechanisms of drug-induced BP: (1) the drug affects the immune regulation of T-regulatory cells and releases autoantibodies against the BMZ, (2) the drugs are perceived as pathogenic antigens leading to autoantibody formation, (3) some drugs act as antigenic haptens, which bind and modify protein molecules on the basement membrane, producing specific autoantibodies, and (4) drugs containing sulfhydryl groups directly destroy the dermal-epidermal junction, thereby exposing autoantigens. Since BP and MMP are both AIBDs, we propose that the pathogenetic mechanisms of enalapril maleate-induced MMP are similar to that of drug-induced BP.

In conclusion, we advise to closely monitor to patients presenting with repeated erosion and blisters in the oral mucosa. Furthermore, histopathology, DIF, IIF, and ELISA should be used to assess the patient’s condition and make a diagnosis. The patient’s medical history can also be beneficial for identifying the causative factors, as in our case, where we identified and excluded the inducing factor during treatment. This idea is especially true given the mounting evidence regarding a correlation between specific medications and MMP.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- AIBD:

-

Autoimmune blistering disease

- BP:

-

Bullous pemphigoid

- DIF:

-

Direct immunofluorescence

- MMP:

-

Mucous membrane pemphigoid

- Ig:

-

Immunoglobin

- DSG:

-

Desmoglein

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme¬-linked immunosorbent assay

- HCTZ:

-

Hydrochlorothiazide

- C3:

-

Complement factor 3

- BMZ:

-

Basement membrane zone

- COL17:

-

Type XVII collagen

- COL7:

-

Type VII collagen

- IIF:

-

Indirect immunofluorescence

References

Carey B, Setterfield J. Mucous membrane pemphigoid and oral blistering diseases. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:732–9.

Daniel BS, Murrell DF. Review of autoimmune blistering diseases: the pemphigoid diseases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2019;33:1685–94.

Alrashdan MS, Kamaguchi M. Management of mucous membrane pemphigoid: a literature review and update. Eur J Dermatol. 2022;32:312–21.

Du G, Patzelt S, van Beek N, Schmidt E. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2022;21:103036.

Xu HH, Werth VP, Parisi E, Sollecito TP. Mucous membrane pemphigoid. Dent Clin North Am. 2013;57:611–30.

Vassileva S. Drug-induced pemphigoid: bullous and cicatricial. Clin Dermatol. 1998;16:379–87.

Haug V, Behle V, Benoit S, Kneitz H, Schilling B, Goebeler M, et al. Pembrolizumab-associated mucous membrane pemphigoid in a patient with Merkel cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:993–4.

Sibaud V, Vigarios E, Siegfried A, Bost C, Meyer N, Pages-Laurent C. Nivolumab-related mucous membrane pemphigoid. Eur J Cancer. 2019;121:172–6.

Kulkarni R, E TS TPS. Oral mucous membrane pemphigoid: updates in diagnosis and management. Br Dent J. 2024;236:293–6.

Hofmann SC, Günther C, Böckle BC, Didona D, Ehrchen J, Gaskins M, et al. S2k Guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of mucous membrane pemphigoid. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2022;20:1530–50.

Kamaguchi M, Iwata H. The diagnosis and blistering mechanisms of mucous membrane Pemphigoid. Front Immunol. 2019;10:34.

Schmidt E, Rashid H, Marzano AV, Lamberts A, Di Zenzo G, Diercks GFH, et al. European guidelines (S3) on diagnosis and management of mucous membrane pemphigoid, initiated by the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology - Part II. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2021;35:1926–48.

Buonavoglia A, Leone P, Dammacco R, Di Lernia G, Petruzzi M, Bonamonte D, et al. Pemphigus and mucous membrane pemphigoid: an update from diagnosis to therapy. Autoimmun Rev. 2019;18:349–58.

Kanjanabuch P, Arporniem S, Thamrat S, Thumasombut P. Mucous membrane pemphigoid in a patient with hypertension treated with atenolol: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2012;6:373.

Fyhrquist F. Clinical pharmacology of the ACE inhibitors. Drugs. 1986;32(Suppl 5):33–9.

Song JC, White CM. Clinical pharmacokinetics and selective pharmacodynamics of new angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitors: an update. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2002;41:207–24.

Forslund T, Tohmo H, Weckström G, Stenborg M, Järvinen S. Angio-Oedema induced by enalapril. J Intern Med. 1995;238:179–81.

Pietkiewicz P, Gornowicz-Porowska J, Bowszyc-Dmochowska M, Dmochowski M. A retrospective study of antihypertensives in pemphigus: a still unchartered odyssey particularly between thiols, amides and phenols. Arch Med Sci. 2015;11:1021–7.

Smith EP, Taylor TB, Meyer LJ, Zone JJ. Antigen identification in drug-induced bullous pemphigoid. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:879–82.

Adriano AR, Gomes Neto A, Hamester GR, Nunes DH, Di Giunta G. Pemphigus vegetans induced by use of enalapril. Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:1197–200.

Bağcı IS, Horváth ON, Ruzicka T, Sárdy M. Bullous pemphigoid. Autoimmun Rev. 2017;16:445–55.

Bisht K, Khuraijam S, Theresa Sony H, Kumbhar S. An Urticarial and Acral Manifestation of Bullous Pemphigoid after Vildagliptin Therapy: a Case Report. Cureus. 2024;16:e57054.

Sonego B, Zelin E, Zalaudek I, di Meo N. Bullous pemphigoid triggered by dulaglutide: a case report and a review of the literature. Dermatol Rep. 2023;15:9676.

Dyson SM, Patel PU, Igali L, Millington GWM. Bullous pemphigoid in a patient with a neuropsychological disorder and a possible novel drug trigger: a case report and review of the literature. Skin Health Dis. 2022;2:e176.

Armanious M, AbuHilal M. Gliptin-Induced Bullous Pemphigoid: Canadian Case Series of 10 patients. J Cutan Med Surg. 2021;25:163–8.

Liang JC, Raman K, Chan SH, Tashakkor AY. Rivaroxaban-Associated Bullous Pemphigoid in a patient with Atrial Fibrillation. CJC Open. 2021;3:1316–9.

Stavropoulos PG, Soura E, Antoniou C. Drug-induced pemphigoid: a review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1133–40.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the patient for cooperating and consenting to this publication.

Funding

The National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) (Grant Nos. 82103673 and 82002877) contributed to the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XFZ and XZ: Administrative, technical, and material support; study supervision; conceptualization and design of the manuscript.YHX, QYZ, LY, JKW: Data acquisition.YHX, QYZ, XFZ, and XZ: Manuscript writing, reviewing, and revision.All authors approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Furthermore, all authors ensured that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work were appropriately investigated and resolved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethics committee of West China Hospital of Stomatology, Sichuan University, approved this study. The patient in this manuscript provided written informed consent for participation.

Consent for publication

The patient in this manuscript provided written informed consent for publishing this case.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xie, Y., Zhang, Q., Ye, L. et al. The first description of mucous membrane pemphigoid induced by enalapril maleate: a case report. BMC Oral Health 24, 1096 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04865-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-024-04865-8