Abstract

Background

Controlling the 3D movement of central incisors during tooth extraction cases with clear aligners is important but challenging in invisible orthodontic treatment. This study aimed to explore the biomechanical effects of central incisors in tooth extraction cases with clear aligners under different power ridge design schemes and propose appropriate advice for orthodontic clinic.

Methods

A series of Finite Element models was constructed to simulate anterior teeth retraction or no retraction with different power ridge designs. These models all consisted of maxillary dentition with extracted first premolars, alveolar bone, periodontal ligaments and clear aligner. And the biomechanical effects were analysed and compared in each model.

Results

For the model of anterior teeth retraction without power ridge and for the model of anterior teeth no retraction with a single power ridge, the central incisors exhibited crown lingual inclination and relative extrusion. For the model of anterior teeth no retraction with double power ridges, the central incisors tended to have crown labial inclination and relative intrusion. For the model of anterior tooth retraction with double power ridges, the central incisors exhibited a similar trend to the first kind of model, but as the depth of the power ridge increased, there was a gradual decrease in crown retraction value and an increase in crown extrusion value. The simulated results showed that von-Mises stress concentration was observed in the cervical and apical regions of the periodontal ligaments of the central incisors. The clear aligner connection areas of adjacent teeth and power ridge areas also exhibited von-Mises stress concentration and the addition of power ridge caused the clear aligner to spread out on the labial and lingual sides.

Conclusions

The central incisors are prone to losing torque and extruding in tooth extraction cases. Double power ridges have a certain root torque effect when there are no auxiliary designs, but they still cannot rescue tooth inclination during tooth retraction period. For tooth translation, it may be a better clinical procedure to change the one-step aligner design to two-step process: tilting retraction and root control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With the increasing demand for cosmetic treatments, traditional fixed appliances can no longer meet the aesthetic needs of orthodontic patients. The concept of modern orthodontics not only requires improving the patient’s aesthetic appearance after orthodontic treatment, but also aims to achieve aesthetic standards in the process of treatment. In early years, lingual appliances were popular among orthodontic patients due to their excellent aesthetic effects [1]. Clear aligners have emerged with the development of computer science and technology. Of all appliances, clear aligners are the most beautiful, comfortable, convenient, and beneficial for oral hygiene. Additionally, using clear aligner treatment greatly reduces the amount of time spent in the doctor’s chair [2,3,4,5,6]. Therefore, the clear aligners have quickly become the favourite of the orthodontic industry.

Clear aligners are a series of transparent, elastic, movable correction devices designed and manufactured by digital technology. Each step of the aligners differs slightly from the current position of the teeth. The teeth are gradually moved to the target position by the elastic restoring force generated when wearing the aligner on the crown, and each-step aligner is designed to move teeth by 0.1-0.3 mm. Patients are required to wear each-step aligner for approximately two weeks, and for at least 20 h per day [7, 8].

Of course, clear aligners also have some limitations. For example, the lack of specific force application points can lead to insufficient force on teeth, and materials are prone to aging in the oral cavity. Therefore, tooth movement efficiency is not always as good as predicted. Moreover, some patients may require multiple stages of intermediate refinement or additional aligners, and even need to switch to fixed orthodontics before completing the treatment [9,10,11]. However, because the advantages of clear aligners far outweigh the disadvantages, invisible orthodontics continues to thrive and improve.

Early studies have shown that clear aligners perform well in distal movement of maxillary molars, alignment of anterior teeth, and expansion of the anterior arch. However, they are not effective in extruding anterior teeth, rotating round teeth or translating teeth [11,12,13,14,15,16]. With the rapid development of materials science and manufacturing technology, invisible orthodontic technology has been continuously improved, expanding its indications from initial mild to moderate malocclusion to complex malocclusion cases that include tooth extraction [17,18,19].

In orthodontic clinic, crowded dentition and protruding profile are common complaints that often require tooth extraction. En-mass retraction of anterior teeth is a commonly used method for closing the extraction space [20]. Whether in fixed orthodontics or invisible orthodontics, the accuracy of 3D control of upper incisors is crucial as the position and angle of anterior teeth are closely related to final aesthetics [21]. For invisible orthodontics, 3D control is more difficult because moving the teeth with clear aligner alone is more likely to induce “the roller coaster effects”, such as torque loss and overbite deepening of anterior teeth. This can lead to unsatisfactory aesthetic results when orthodontic treatment is finished [22,23,24]. For example, Li et al. compared the tooth movement effects of invisible orthodontics and fixed orthodontics, and found that the control effect of fixed orthodontics was better than that of invisible orthodontics [25]. Furthermore, Dai et al. investigated the actual and predicted movements of central incisors in cases where first premolars were extracted, and discovered that compared to the predictions, the lingual inclination of the central incisor was greater while extrusion was more and retraction was less [18, 19].

A ‘power ridge’ has been designed on the clear aligners corresponding to the incisors in invisible orthodontics, especially in tooth extraction cases, for better control the torque of incisors. Some scholars have confirmed that adding a power ridge to the labial gingival area of the upper central incisor has a better torque control effect than using a horizontal ellipsoid attachment [12, 26]. Cheng et al.’s study shows that clear aligners of different thicknesses need to be combined with different height power ridges to achieve bodily movement of central incisors, 0.5 mm-thick aligner better accompanied with a power ridge of 0.7 mm while 0.75 mm-thick aligner better accompanied with a power ridge of 0.25 mm [24]. However, it is unclear how the addition of power ridges to the clear aligner system will affect its overall performance and whether different designs of power ridges will have varying biomechanical effects on the incisors.

The aim of this study was to investigate the biomechanical effects of invisible orthodontic extraction cases and the influence of different power ridge designs on tooth movement, as well as to explore the appropriate design of 3D control scheme of anterior teeth in tooth extraction cases. Due to the complexity of the orthodontic force system, in vivo research is not feasible [27,28,29]. In this study, the stress, strain and displacement of the orthodontic loading model was calculated using 3D Finite Element Method, which has strong repeatability [30,31,32].

Methods

Original data and designs

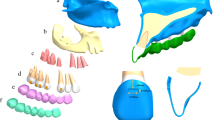

An adult orthodontic patient (female, 26 years old, from Department of Orthodontics, Stomatological Hospital of Chongqing Medical University) with a protrude profile was selected, her teeth, mucosa and periodontal tissue were healthy, and she had no temporomandibular joint or other lesions. After the maxillary bilateral first premolars were extracted and the maxillary dentition was aligned, the dental cone-beam computed tomography scan of the patient was obtained and saved. The data of right maxillary alveolar bone and dentition were input into Mimics19.0 software (Materialise, Leuven, Belgium) to construct the initial model. After smoothed and mirrored by GeomagicStudio2015 software (Geomagic, Morrisville, NC, USA) and SolidWorks2016 software (Dassault Systems, Concord, MA, USA), the bilaterally symmetrical maxillary bone (Fig. 1a) and maxillary dentition (Fig. 1b) were reconstructed. Periodontal ligaments (Fig. 1c) with an average thickness of 0.2 mm [33] were constructed along the root anatomy while the aligner (Fig. 1d) with an average thickness of 0.75 mm [34] was constructed along the crown anatomy (Supplementary Methods). Therefore, each model was consisted of maxillary dentition with extracted first premolars, alveolar bone, periodontal ligaments and clear aligner. All components were combined to generate an assembly (Fig. 1e).

For our four major groups, all were each-step aligner designs and only the clear aligner differ among each group. The aligner models were designed as follows (Fig. 2):

-

Model G0 (Fig. 2a), the clear aligner was constructed based on the crown position (anterior teeth (from 13 to 23) en-masse retracted 0.2 mm) without power ridge. This simulated the situation that the anterior teeth were retracted by the aligner alone without any auxiliary accessories. The goal of this design was to verify whether using clear aligner alone can achieve the effect of translation of anterior teeth.

-

Model G1 (Fig. 2b), the clear aligner was constructed based on the original crown position, which featured power ridge at central incisor labial side. This simulated the situation that a single power ridge acted on the central incisor without tooth movement designs. The goal of this design was to verify whether a single power ridge can achieve the effect of root control.

-

Model G2 (Fig. 2c), the clear aligner was constructed based on the original crown position, which featured power ridges at central incisor both labial side and lingual side. This simulated the situation that double power ridges acted on the central incisor without tooth movement designs. The goal of this design was to verify whether double power ridges can achieve the effect of root control.

-

Model G3 (Fig. 2d), the clear aligner was constructed based on the crown position (anterior teeth (from 13 to 23) en-masse retracted 0.2 mm) with power ridges at central incisor both labial side and lingual side. This simulated the comprehensive situation of retracting anterior teeth with double power ridges. The goal of this design was to verify whether adding double power ridges to the clear aligner has better translation effect during anterior teeth retraction period compared with the same situation without power ridge.

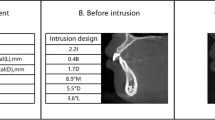

The power ridges were located at gingival third of labial side and the incisal third of lingual side, which was rectangular with 3 mm long and 1 mm wide determined according to clinical measurement. For G1-G3, four kinds of power ridge depths were designed including 0.2 mm, 0.3 mm, 0.4 and 0.5 mm (written as G1-0.2, G1-0.3, G1-0.4, G1-0.5, etc.). The clear aligner models were built in the anterior teeth retracted positions in G0 and G3, but in the original tooth positions in G1 and G2. For ease of description, the positions built clear aligners were collectively called the target positions of tooth movement. All models were imported into the Finite Element software Abaqus6.14 (Simulia, France) for calculations.

Material properties and meshing

The material properties (Table 1) were established according to previous studies [35,36,37,38]. The clear aligner was set large deformation, and the adaptive mesh division method provided by Abaqus6.14 software was used to freely divide the mesh. The mesh sizes for tooth, alveolar bone, periodontal ligament and clear aligner were 1.0 mm, 2.0 mm, 0.5 and 0.6 mm, respectively. Mesh sizes were defined after the preliminary experiment results converged (Fig. S1). The numbers of nodes and elements are shown in Table 2.

Boundary constraints and contact conditions

The base of the alveolar bone was set fixed constraint, and the whole model was set symmetry constraint with the mid-sagittal plane as the symmetry axis. The interfaces between the tooth and periodontal ligament and between the periodontal ligament and alveolar bone were set bonded contact. A nonlinear surface-to-surface contact relationship between the outer surface of the crown and the inner surface of the clear aligner was set, with a friction coefficient of µ = 0.2 [39], no constraints or loads were applied to the tooth or the clear aligner (Fig. S2).

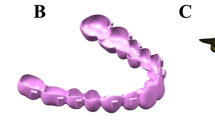

Activation of tooth movement calculation. The crowns and clear aligners overlapped each other in the anterior tooth regions in the assembly models (Fig. 2), for the clear aligners were built at the target positions of tooth movement while the tooth models were at original positions in all assembly models. Although the aligners of G1 and G2 were constructed based on the original tooth positions, the power ridge is the ridge that bulge inward based on the outer surface of the crown, so there was still overlap between the aligners and the central incisor crowns. Our calculation simulated the process of wearing clear aligners onto the crowns (Fig. 3a), which was similar to contact interference assembly in mechanical engineering [40].

Interference assembly is initial interference between the two assembly models, as the object develops stress deformation, it is tightly assembled together. In our study, the surface-to-surface contact pairs algorithm was adopted which composed of a master surface and a slave surface (Fig. S2). The crown surface with high stiffness was set as the master surface, and clear aligner was set as the slave surface. All contact directions were along the normal direction of the master surface, and the nodes on the slave surface could not penetrate the master surface, but the nodes on the master surface could penetrate the slave surface. In order to resolve the interference between the clear aligner and the crown, the automatic shrink fit algorithm [41,42,43] which gradually removed slave node over-closure during the analysis step was applied to resolve the interference, the tooth moved towards the target position of the clear aligner also with clear aligner moved towards the tooth to change the mismatch into match, thus activated the calculation process of invisible orthodontics automatically. The interference resulted in stresses and strains in the model as over-closure was resolved (Figs. S3 and S4).

Coordinate system setting

The x-axis, y-axis and z-axis of the 3D coordinate represent the coronal direction, sagittal direction and vertical direction, respectively (Fig. 1f); and the distal, labial, and root directions of the right central incisor indicate the positive directions of the x-axis, y-axis and z-axis, respectively.

Calculation and analysis

The nonlinear iterative calculations (Supplementary Methods, Figs. S3 and S4) were carried out by Abaqus, and the items analysed included:

-

initial displacement patterns of central incisors.

-

von-Mises stress distributions of periodontal ligaments of central incisors.

-

deformation trends and von-Mises stress distributions of clear aligners.

Results

For the displacement patterns of central incisors, the crowns and roots exhibited movements in the opposite directions in each axis except the z-axis of G3, the results are shown in Figs. 3, 4 and 5.

-

G0: The central incisor showed distal crown tipping, lingual crown tipping and crown relative extrusion (Fig. 3b and c).

-

G1: The displacement patterns of all subgroups were similar; as the depth of the power ridge increased, the displacement values of both crowns and roots increased exclude the root displacement of G1-0.2. Each subgroup showed mesial crown inclination. Besides, lingual crown tipping with crown mesial lingual torsion and crown relative extrusion were observed (Figs. 4 and 5).

-

G2: The displacement patterns of all subgroups were also analogous; as the power ridge depth increased, the displacements of central incisors also increased. It showed mesial crown inclination and labial crown tipping. Besides, crown relative intrusion was observed (Figs. 4 and 5).

-

G3: All subgroups showed mesial crown inclination which similar to G1 and G2. In the sagittal direction, all subgroups showed lingual crown tipping; unlike G1 and G2, as the depth of the power ridge increased, the displacements of crowns gradually decreased but the displacements of roots gradually increased. G3-0.2 showed crown relative extrusion and root relative intrusion, whereas the other subgroups showed absolute tooth extrusion (Figs. 4 and 5).

The cervical areas and root apexes of periodontal ligaments of all central incisors revealed von-Mises stress concentrations (Fig. 6a), which were consistent with tooth displacement patterns. For G1-G3, as the depth of the power ridge increased, the peak values of von-Mises stress increased gradually (Fig. 6b).

The addition of power ridges caused the clear aligner to spread out on the labial and lingual sides in each model (Fig. 7a). As the power ridge depth increased, the spreading degree gradually increased (Fig. 7b), but the maximum deformation values were all located at the labial cervical areas of clear aligners (Fig. 7a).

The connection areas between adjacent teeth appeared von-Mises stress concentration in each group; besides, von-Mises stress concentration also showed on the power ridge areas in G1 and the power ridge areas and the incisal edges in G2 and G3 (Fig. 8a). The clear aligners with double power ridges exhibited lager peak values of von-Mises stress than the aligners without power ridge or with a single power ridge (Fig. 8b).

Discussion

The efficiency of tooth movement in invisible orthodontics has been the focus of many previous studies [12,13,14,15,16], but its biomechanics are still not very clear [8, 19, 44]. In recent years, several Finite Element studies have attempted to explore the biomechanical effects of invisible orthodontics. However, those models were mainly based on one or several teeth and applied direct force to the teeth or displacement load on clear aligners to simulate the invisible orthodontic process. These approaches differ significantly from real clinical situations [39, 44,45,46]. Additionally, there is limited research on the use of invisible treatment for cases involving tooth extraction. In orthodontic clinic, the clear aligner exerts orthodontic force to correct malocclusion by deforming due to misalignment with the dentition position. This process is similar to the theory of interference assembly in mechanical engineering [40]. Interference assembly refers to the initial interference between two assembly models, which become tightly assembled together as stress deformation occurs. This process is similar to wearing clear aligners on teeth. To simulate an interference fit, a special algorithm called automatic shrink fit [41] was used in this study. Interferometers were gradually eliminated during analysis and calculation, and deformation stresses were generated. Therefore, our simulation was reasonable and highly consistent with clinical practice.

In extraction cases, sagittal and vertical controls of central incisors are crucial, especially sagittal control. Our results indicate that the central incisor exhibited a loss of torque and tendency towards deepening overbite in G0 (Fig. 3b), which is consistent with the findings of Dai et al. [18, 19, 24]. In G1, a counterclockwise (mesial view) movement pattern in the sagittal direction was observed, along with an increase in overbite in the vertical direction (Fig. 4). However, in G2, the central incisors exhibited a clockwise (mesial view) movement pattern in the sagittal direction and there was a decrease in overbite in the vertical direction (Fig. 4). In the absence of other designs, single power ridge has no effect on lingual root torque or opening occlusion. However, double power ridges appear to have an effect. Therefore, we designed G3 with the expectation of achieving better 3D control of central incisors and achieving the desired effect of tooth translation.

Unfortunately, the result was not ideal. In orthodontic clinic, the absolute value of the crown-root displacement ratio in the sagittal direction can be used to evaluate the degree of tooth translation. When the direction of crown and root displacement is opposite, the larger the absolute value of crown-root displacement ratio, the more likely teeth are to move bodily. From the results, we can see that although double power ridges have a certain torque control effect in situ, adding them during anterior teeth retraction cannot achieve tooth translation and may even significantly sacrifice the amount of retraction displacement. As the power ridges deepen, the teeth become increasingly oblique, resulting in less displacement of crown retraction and greater labial inclination of the root, which was not desirable (Figs. 3, 4 and 5; Table 3). Compared with G0, even though the root labial movement of G3-0.2 reduced, the displacement of crown retraction also reduced, the absolute value of crown-root displacement ratio was still smaller than G0 (Figs. 3c and 5; Table 3), so the teeth tended to move more obliquely than G0. In the vertical direction, the power ridges did not reduce the overbite but deepened it (Figs. 3c and 5a). On the other hand, we compared the maximum stresses of periodontal ligaments in both G0 and G3, from which we can see that with the depth of power ridges increased, the maximum von-Mises stress of periodontal ligament also increased, only the stress of G3-0.2 was smaller than G0 (Fig. 6b). Therefore, according to the absolute values of crown-root displacement ratio in sagittal direction and the stresses of periodontal ligaments, it can be inferred that the addition of power ridges during the anterior teeth retraction period cannot achieve the desired effect.

From the results of this study, there were no significant differences in tooth displacement patterns between different power ridge depth designs (Fig. 4), but increasing the depth resulted in higher tooth displacement values (Fig. 5). In addition, the results of G0 showed that retracting anterior teeth with clear aligners alone could lead to tooth tipping (Fig. 3b). G2 and G3 demonstrated that double power ridges controlled lingual root torque in situ, but adding them during the retraction period had an adverse effect (Fig. 4). This indicates that the invisible orthodontic system is a very complex mechanical system, and its comprehensive effects are not simply a superposition of individual outcomes when it comes to tooth translation. When tooth translation cannot be achieved by one step, changing procedure to two steps of tilting retraction and root control may be a good choice.

Root resorption caused by excessive orthodontic force is also a concern in orthodontic treatment. Gay et al. measured root resorption during Invisalign clear aligner treatment and found that 81% of the 1083 teeth measured showed a reduction in root length compared to pre-treatment levels [47]. Another study analysed a total of 640 teeth for root length alteration in orthodontics, with 320 in fixed orthodontics and 320 in invisible orthodontics. The mean percentage value of external apical root resorption in the invisible orthodontics group was 5.13 ± 2.81%, which was significantly less than that of the fixed orthodontics group (6.97 ± 3.67%) [47]. In this study, all periodontal ligament apexes showed high levels of von-Mises stress concentration (Fig. 6a), indicating that the root apexes of the central incisors were subjected to significant stress. Additionally, as the depth of power ridges increased, so did the von-Mises stress, thereby the risk of root resorption could not be ignored. Therefore, orthodontists should control orthodontic force within an appropriate range by reducing step distance or power ridge depth to minimize root resorption.

The efficiency of tooth movement in invisible orthodontics largely depends on the fit between the clear aligner and crown [29, 48]. Our study found that the presence of a power ridge could lead to a lack of fit between the clear aligner and crown and increasing power ridge depth resulted in a greater degree of nonfit (Fig. 7), which may affect the wearing of the clear aligner, potentially impacting the effectiveness of orthodontic treatment. However, as mentioned before, increasing the depth of the power ridge could lead to increasing of tooth displacement if bone necrosis is not taken into consideration. Therefore, orthodontists should carefully consider both the positive and negative effects in order to create a comprehensive design.

In addition, each simulated model showed von-Mises stress concentration in the joint areas of adjacent teeth in the anterior part (Fig. 8a). It is evident that these areas are particularly susceptible to fracture or plastic deformation of clear aligners due to stress concentration. Therefore, it is necessary to reinforce the connection areas between adjacent teeth or improve the mechanical properties of materials used in these areas to reduce the risk of breakage.

Previous data shows that relying clear aligners alone cannot solve all the malocclusion deformities [49, 50]. Attachments play a crucial role in the process of invisible orthodontics, enabling better orthodontic force transmission to teeth, assisting tooth movement, and increasing aligners retention. The addition of attachments may help reduce the need for additional aligners, reduce the overall treatment duration, and provide more predictable treatment results than those with clear aligners alone [9]. Numerous studies have confirmed that the addition of attachments can significantly improve tooth movement efficiency compared to the absence of attachments [9, 51]. However, as the purpose of this study was to investigate the original biomechanical properties of the invisible orthodontic system, no attachment was designed in this study. Subsequent studies can try to add attachments, elasticity and other auxiliary devices, which may obtain different biomechanical effects.

As an efficient mathematical simulation method, Finite Element Method can reproduce complex geometric shapes and their physical characteristics on computers to evaluate their behavior after applying force, and is widely used in the dental field [52]. However, this method also has certain limitations which may lead to deviations between the simulation result and the actual one, such as the inability to truly simulate the oral environment, including temperature and saliva inside the mouth, as well as personalized bone morphology of different patients [53]. The simulation result largely depends on the parameter settings of the materials, and cannot simulate the dynamic changes of the dental system under long-term force loading and the clear aligner itself [24]. Therefore, although this simulated study helps us have intuitive understanding of the biomechanical effects of invisible orthodontics on anterior teeth retraction in tooth extraction cases, long-term and clinical trials are still needed to verify the results given in this study.

Another limitation that should be pointed out is that 13 complete maxillary models were constructed in this study, but only the central incisors were targeted designed and analysed. The force state of the whole dentitions were not thoroughly analysed. Therefore, future designs should include all teeth and analyse the biomechanical effects of the entire invisible orthodontic system to gain a deeper understanding.

Conclusions

Within the limitations of this study, it can be concluded that in cases of invisible orthodontics involving first premolar extraction, there is a tendency for the central incisors to lose torque and extrude. Without other designs, a single power ridge does not have a lingual root torque effect, while double power ridges do. Tooth displacement patterns did not show significant differences among different power ridge depth designs, but increasing the depth of the power ridge could lead to an increase in tooth displacement value. When tooth translation cannot be achieved in one step, it is recommended to modify the clinical design of invisible orthodontics to include two steps: tilting retraction and root control.

Data Availability

The data used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Awad MG, Skander E, Ashley S, Vaid N, Makki L, Ferguson DJ. Accuracy of digital predictions with CAD/CAM labial and lingual appliances a retrospective cohort study. Semin Orthod. 2018;24(4):14.

Noll D, Mahon B, Shroff B, Carrico C, Lindauer SJ. Twitter analysis of the orthodontic patient experience with braces vs Invisalign. Angle Orthod. 2017;87(3):377–83.

White DW, Julien KC, Jacob H, Campbell PM, Buschang PH. Discomfort associated with Invisalign and traditional brackets: a randomized, prospective trial. Angle Orthod. 2017;87(6):801–8.

Tamer I, Oztas E, Marsan G. Orthodontic Treatment with Clear Aligners and the scientific reality behind their marketing: a Literature Review. Turk J Orthod. 2019;32(4):241–6.

Boyd RL. Esthetic orthodontic treatment using the invisalign appliance for moderate to complex malocclusions. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(8):948–67.

Marya A, Venugopal A, Vaid N, Alam MK, Karobari MI. Essential attributes of Clear Aligner Therapy in terms of Appliance Configuration, Hygiene, and Pain levels during the pandemic: a brief review. Pain Res Manag. 2020;2020:6677929.

Almasoud NN. Pain perception among patients treated with passive self-ligating fixed appliances and Invisalign((R)) aligners during the first week of orthodontic treatment. Korean J Orthod. 2018;48(5):326–32.

Barone S, Paoli A, Razionale AV, Savignano R. Computational design and engineering of polymeric orthodontic aligners. Int J Numer Method Biomed Eng. 2017;33(8):e2839.

Vaid NR, Sabouni W, Wilmes B, Bichu YM, Thakkar DP, Adel SM. Customized adjuncts with clear aligner therapy: “The Golden Circle Model” explained! J World Fed Orthod. 2022;11(6):216–25.

Kravitz ND, Dalloul B, Zaid YA, Shah C, Vaid NR. What percentage of patients switch from Invisalign to braces? A retrospective study evaluating the conversion rate, number of refinement scans, and length of treatment. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2023;163(4):526–30.

Fiori A, Minervini G, Nucci L, d’Apuzzo F, Perillo L, Grassia V. Predictability of crowding resolution in clear aligner treatment. Prog Orthod. 2022;23(1):43.

Simon M, Keilig L, Schwarze J, Jung BA, Bourauel C. Treatment outcome and efficacy of an aligner technique – regarding incisor torque, premolar derotation and molar distalization. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:68.

Rossini G, Parrini S, Castroflorio T, Deregibus A, Debernardi CL. Efficacy of clear aligners in controlling orthodontic tooth movement: a systematic review. Angle Orthod. 2015;85(5):881–9.

Gu J, Tang JS, Skulski B, Fields HW Jr, Beck FM, Firestone AR, et al. Evaluation of Invisalign treatment effectiveness and efficiency compared with conventional fixed appliances using the peer Assessment Rating index. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;151(2):259–66.

Ke Y, Zhu Y, Zhu M. A comparison of treatment effectiveness between clear aligner and fixed appliance therapies. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19(1):24.

Galan-Lopez L, Barcia-Gonzalez J, Plasencia E. A systematic review of the accuracy and efficiency of dental movements with Invisalign(R). Korean J Orthod. 2019;49(3):140–9.

Zheng M, Liu R, Ni Z, Yu Z. Efficiency, effectiveness and treatment stability of clear aligners: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Orthod Craniofac Res. 2017;20(3):127–33.

Dai FF, Xu TM, Shu G. Comparison of achieved and predicted crown movement in adults after 4 first premolar extraction treatment with Invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2021;160(6):805–13.

Dai FF, Xu TM, Shu G. Comparison of achieved and predicted tooth movement of maxillary first molars and central incisors: first premolar extraction treatment with Invisalign. Angle Orthod. 2019;89(5):679–87.

Dardengo Cde S, Fernandes LQ, Capelli Junior J. Frequency of orthodontic extraction. Dent Press J Orthod. 2016;21(1):54–9.

Mishra D, Natarajan M, Urala AS. Lip profile changes in patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusion of varied growth patterns treated with maxillary premolar extractions: a pilot study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158(5):684–93.

Liang W, Rong Q, Lin J, Xu B. Torque control of the maxillary incisors in lingual and labial orthodontics: a 3-dimensional finite element analysis. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2009;135(3):316–22.

Sfondrini MF, Gandini P, Castroflorio T, Garino F, Mergati L, D’Anca K, et al. Buccolingual Inclination Control of Upper Central Incisors of Aligners: a comparison with conventional and self-ligating brackets. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:9341821.

Cheng Y, Liu X, Chen X, Li X, Fang S, Wang W, et al. The three-dimensional displacement tendency of teeth depending on incisor torque compensation with clear aligners of different thicknesses in cases of extraction: a finite element study. BMC Oral Health. 2022;22(1):499.

Li W, Wang S, Zhang Y. The effectiveness of the Invisalign appliance in extraction cases using the the ABO model grading system a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(5):8276–82.

Simon M, Keilig L, Schwarze J, Jung BA, Bourauel C. Forces and moments generated by removable thermoplastic aligners: incisor torque, premolar derotation, and molar distalization. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2014;145(6):728–36.

Milheiro A, de Jager N, Feilzer AJ, Kleverlaan CJ. In vitro debonding of orthodontic retainers analyzed with finite element analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2015;37(5):491–6.

Elkholy F, Schmidt F, Jager R, Lapatki BG. Forces and moments applied during derotation of a maxillary central incisor with thinner aligners: an in-vitro study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2017;151(2):407–15.

Cortona A, Rossini G, Parrini S, Deregibus A, Castroflorio T. Clear aligner orthodontic therapy of rotated mandibular round-shaped teeth: a finite element study. Angle Orthod. 2020;90(2):247–54.

Shen T, Zhao B, Wang C, Xiao Y, Han Y, Zhao G, et al. Efficacy of different designs of mandibular expanders: a 3-dimensional finite element study. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;157(5):641–50.

Zeng W, Liu Y, Hou X. Biomechanical evaluation of internal fixation implants for femoral neck fractures: a comparative finite element analysis. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;196:105714.

Harikrishnan P, Magesh V, Ajayan AM, JebaSingh DK. Finite element analysis of torque induced orthodontic bracket slot deformation in various bracket-archwire contact assembly. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;197:105748.

Wang C, Han J, Li Q, Wang L, Fan Y. Simulation of bone remodelling in orthodontic treatment. Comput Methods Biomech Biomed Engin. 2014;17(9):1042–50.

Savignano R, Valentino R, Razionale AV, Michelotti A, Barone S, D’Anto V. Biomechanical Effects of different auxiliary-aligner designs for the extrusion of an Upper Central Incisor: a finite element analysis. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:9687127.

Xu B, Wang Y, Li Q. Modeling of damage driven fracture failure of fiber post-restored teeth. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater. 2015;49:277–89.

Bachiri A, Djebbar N, Boutabout B, Serier B. Effect of different impactor designs on biomechanical behavior in the interface bone-implant: a comparative biomechanics study. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;197:105723.

Eram A, Zuber M, Keni LG, Kalburgi S, Naik R, Bhandary S, et al. Finite element analysis of immature teeth filled with MTA, Biodentine and Bioaggregate. Comput Methods Programs Biomed. 2020;190:105356.

Xie Q, Li D. The cross-sectional effects of ribbon arch wires on class II malocclusion intermaxillary traction: a three-dimensional finite element analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2021;21(1):501.

Gomez JP, Pena FM, Martinez V, Giraldo DC, Cardona CI. Initial force systems during bodily tooth movement with plastic aligners and composite attachments: a three-dimensional finite element analysis. Angle Orthod. 2015;85(3):454–60.

Jiang T, Wu RY, Wang JK, Wang HH, Tang GH. Clear aligners for maxillary anterior en masse retraction: a 3D finite element study. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):10156.

Ozturk F. Finite-element modelling of two-disc shrink fit assembly and an evaluation of material pairs of discs. Proc Institution Mech Eng Part C: J Mech Eng Sci. 2010;225(2):263–73.

Pedersen P. On Shrink Fit Analysis and Design. Comput Mech. 2005;37(2):121–30.

Özel A, Temiz Ş, Aydin MD, Şen S. Stress analysis of shrink-fitted joints for various fit forms via finite element method. Mater Design. 2005;26(4):281–9.

Liu Y, Hu W. Force changes associated with different intrusion strategies for deep-bite correction by clear aligners. Angle Orthod. 2018;88(6):771–8.

Comba B, Rossini SP, Castroflorio G, Deregibus T. A. A ThreeDimensional Finite Element Analysis of UpperCanine Distalization with Clear Aligners, Composite Attachments, and Class II Elastics. JCO. 2017:24 – 8.

Yokoi Y, Arai A, Kawamura J, Uozumi T, Usui Y, Okafuji N. Effects of attachment of Plastic Aligner in closing of Diastema of Maxillary Dentition by Finite element Method. J Healthc Eng. 2019;2019:1075097.

Gay G, Ravera S, Castroflorio T, Garino F, Rossini G, Parrini S, et al. Root resorption during orthodontic treatment with Invisalign(R): a radiometric study. Prog Orthod. 2017;18(1):12.

Mantovani E, Castroflorio E, Rossini G, Garino F, Cugliari G, Deregibus A, et al. Scanning electron microscopy evaluation of aligner fit on teeth. Angle Orthod. 2018;88(5):596–601.

Upadhyay M, Arqub SA. Biomechanics of clear aligners: hidden truths & first principles. J World Fed Orthod. 2022;11(1):12–21.

Haouili N, Kravitz ND, Vaid NR, Ferguson DJ, Makki L. Has Invisalign improved? A prospective follow-up study on the efficacy of tooth movement with Invisalign. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;158(3):420–5.

Kim WH, Hong K, Lim D, Lee JH, Jung YJ, Kim B. Optimal position of attachment for removable thermoplastic aligner on the Lower Canine using finite element analysis. Mater (Basel). 2020;13(15).

Ahmed T, Padmanabhan S, Pottipalli Sathyanarayana H. Effects of varying attachment positions on palatal displacement of maxillary incisors with clear aligner therapy: a three-dimensional finite element analysis. J Orofac Orthop. 2023;84(3):178–88.

Zhang Y, Gao J, Wang X, Wang J, Zhang X, Fang S, et al. Biomechanical factors in the open gingival embrasure region during the intrusion of mandibular incisors: a new model through finite element analysis. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2023;11:1149472.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by Chongqing Talent Program: Innovative leading talents (Medical field, Grant number CQYC20210303384); Chongqing Medical Scientific Research Project (Grant number 2018ZDXM020); Program for Youth Innovation in Future Medicine, Chongqing Medical University (Grant number W0033); National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 12072055, 11872135, U20A20390); Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (Grant number L212063); and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the 111 Project (Grant number B13003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.L. and M.X. conceived and designed the study. W.CJ. and M.X. set-up and computed the simulations. X.W. acquired the data. W.R. and A.R. analysed the data. W.C. and F.Y. evaluated the data. M.X. wrote and edited the manuscript. Z.L., W.C., M.X and W.CJ. revised the work. All authors commented on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was designed in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Stomatological Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (No. 201904). Prior to this study, an informed consent form was signed by the 26-year-old healthy female volunteer.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Meng, X., Wang, C., Xu, W. et al. Effects of different designs of orthodontic clear aligners on the maxillary central incisors in the tooth extraction cases: a biomechanical study. BMC Oral Health 23, 416 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03106-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-023-03106-8