Abstract

Background

Streptococcus mutans is a common cariogenic bacterium in the oral cavity involved in plaque formation. Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) has been introduced into tooth mousse to encourage remineralization of dental enamel. The aim of this research was to study the effect of tooth mousse containing CPP-ACP (GC Tooth Mousse®) or CPP-ACP with 0.2% fluoride (CPP-ACPF; GC Tooth Mousse Plus®; GCP) on S. mutans planktonic growth and biofilm formation.

Methods

S. mutans was cultivated in the presence of different dilutions of the tooth mousse containing CPP-ACP or CPP-ACPF, and the planktonic growth was determined by ATP viability assay and counting colony-forming units (CFUs). The resulting biofilms were examined by crystal violet staining, MTT metabolic assay, confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM), and scanning electron microscope (SEM).

Results

The CPP-ACP tooth mousse (GC) at a dilution of 5–50 mg/ml (0.5–5%) did not inhibit planktonic growth, and even increased the ATP content and the number of viable bacteria after a 24 h incubation. The same was observed for the CPP-ACPF tooth mousse (GCP), except for the higher concentrations (25 and 50 mg/ml) that led to a drop in the bacterial count. Importantly, both compounds significantly decreased S. mutans biofilm formation at dilutions as low as 1.5–3 mg/ml. 12.5 mg/ml GC and 6.25 mg/ml GCP inhibited biofilm formation by 90% after 4 h. After 24 h, the MBIC90 was 6.25 mg/ml for both. CLSM images confirmed the strong inhibitory effect GC and GCP had on biofilm formation when using 5 mg/ml tooth mousse. SEM images of those bacteria that managed to form biofilm in the presence of 5 mg/ml tooth mousse, showed alterations in the bacterial morphology, where the streptococci appear 25–30% shorter on the average than the control bacteria.

Conclusion

Our data show that the tooth mousse containing CPP-ACP reduces biofilm formation of the cariogenic bacterium S. mutans without killing the bacteria. The use of natural substances which inhibit biofilm development without killing the bacteria, has therapeutic benefits, especially in orthodontic pediatric patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Biofilms are formed when clusters of microorganisms adhere to surfaces and secrete extracellular matrix that assists the further attachment of additional microorganisms [1]. Oral biofilms can appear on teeth, mucosa, restorations, and orthodontic appliances, and play an important role in the etiology of caries, periodontal diseases, and candidiasis [2, 3]. Streptococcus mutans (S. mutans) is a facultative anaerobic Gram-positive bacterium that plays a major role in oral biofilm formation [4]. The bacterium utilizes sucrose to synthesize adhesive fructans and glucans by the respective enzymes fructosyltransferase (FTF) and glucosyltransferase (GTF) [5]. These extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) stick to surfaces, such as the tooth enamel, and together with glucan-binding proteins (GBPs), they act as binding sites for S. mutans and other microbes, thereby forming dental plaques composed of a complex microbe community embedded in an extracellular matrix [5]. Besides contributing to dental plaque formation, S. mutans is highly cariogenic in virtue of its ability to process sucrose from nutritional substances into organic acids that lower the pH within the biofilm, resulting in decalcification of the tooth enamel [6]. The virulence of S. mutans is further enhanced by its ability to survive in an acidic environment [6]. S. mutans embedded in the biofilm express different genes than those expressed in their planktonic form, enabling adaptation to the biofilm setting [7]. The sessile state of the bacteria in the biofilm makes them less sensitive to anti-bacterial agents [7].

The same principles of biofilm formation in the cariogenic process also apply to orthodontic patients. Orthodontic patients present an outstandingly challenging environment that include brackets, bands, and other potential surfaces for biofilm growth. These surfaces make it more difficult to achieve good oral hygiene, which favor the formation of oral biofilms [8,9,10]. As a result, orthodontic treatment may cause enamel demineralization, varying from white spot lesions to cavities, and soft tissue inflammation [11].

The nanocomplexes formed between casein phosphopeptides (CPPs) and amorphous calcium phosphate (ACP) were documented by E.C. Reynolds for three decades ago to have profound anti-cariogenic activity [12]. CPPs are phosphorylated casein-derived peptides made by proteolytic breakdown of the milk products αS1-, αS2-, and β-casein. The CPPs which contain the cluster sequence of Ser(P)-Ser(P)-Ser-(P)-Glu-Glu, stabilize nanoclusters of ACP, resulting in increased calcium phosphate levels in dental plaque [12]. The ability of CPP to buffer free calcium and phosphate ions enables ACP supersaturation relative to the tooth enamel, thus reducing demineralization and enhancing remineralization [12,13,14,15,16]. Thus, CPP-ACP alone or together with fluoride has been suggested to be a novel compound for remineralization of dental enamel, incorporated in varnishes, pastes, lozenges, and dentifrices [17,18,19,20,21].

Tooth Mousse® (MI Paste®) and Tooth Mousse Plus® (MI Paste Plus®) contain 10% casein phosphopeptide–amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) without or with 0.2% NaF, respectively (produced by GC, Tokyo, Japan). These tooth mousse were made based on the innovative study of Reynolds et al. [22] who developed Recaldent® (CPP-ACP technology). Tooth Mousse Plus® contains 900 parts per million fluoride in a molar ratio with the calcium and phosphate of 5 calcium, 3 phosphate and 1 fluoride which was found to be the optimal ratio for generating fluorapatite [22]. The fluoride ions are known to bind to calcium and phosphate ions that are released upon enamel demineralization by plaque bacterial organic acids. Because of the more compact structure of fluorapatite than hydroxyapatite, the fluorapatite better resists acid attack and thus prevents demineralization [23]. The aim of this study was to investigate the effect of Tooth Mousse ("GC") and Tooth Mousse Plus ("GCP") on oral biofilms and oral bacteria in vitro.

Methods

Preparation of tooth mousse suspensions

Tooth Mousse® ("GC"; MI Paste, GC Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and Tooth Mousse Plus® ("GCP"; MI Paste Plus) which contain CPP-ACP and CPP-ACPF, respectively, were resuspended in brain–heart infusion broth (BHI, Acumedia, Lansing, Michigan, USA) or BHI containing 2% sucrose (BHIS) to a concentration of 10%. Then serial dilutions were done in BHI for planktonic bacterial growth or BHIS for biofilm formation studies. The suspension of the tooth mousse in BHI and BHIS had a neutral pH of 7.

Planktonic growth of Streptococcus mutans

For planktonic growth, an overnight culture of S. mutans UA159 was diluted to an optical density (OD) of 0.05 at 600 nm and incubated with different dilutions of the test compounds in 200 μl BHI in 96-flat bottom culture plates (Corning) at 37 °C in 95% air/5% CO2. The planktonic growth in the presence of the test compounds was compared to control bacteria grown in BHI medium. Different dilutions of the test compounds in the absence of bacteria were used to measure background signals.

Microbial cell viability assay

The BacTiter-Glo™ kit (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used to quantify the ATP levels in untreated and treated cells according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, 150 µl of each sample was mixed with 150 µl of the reagent in 96-white μClear flat bottom plates (Greiner Bio-One) for 5 min on an orbital shaker. Thereafter, the luminescence was recorded using the M200 Tecan microplate reader (Tecan Trading AG, Switzerland). Different dilutions of the test compounds in the absence of bacteria were used to measure background signals.

Colony forming units (CFU)

The number of bacteria in the untreated and treated samples was determined by doing repeatedly tenfold serial dilutions in 1 ml BHI and seeding 100 μl of each dilution onto BHI agar plates that were incubated overnight at 37 °C in the presence of 95% air/5% CO2. After incubation, the number of colonies was counted using the ImageJ software. The following equation was used to calculate the CFU per well in the original sample: Number of colonies x dilution factor x original volume of sample.

Biofilm formation by Streptococcus mutans

For biofilm formation, an overnight culture of S. mutans UA159 was diluted to an OD of 0.05 at 600 nm and incubated with different dilutions of the test compounds in 200 μl BHIS in 96-flat bottom culture plates (Corning) at 37 °C in 95% air/5% CO2. At the end of the incubation period, the biofilms were carefully washed with PBS or DDW and quantified by the assays described below. The biofilm formation in the presence of the test compounds was compared to control bacteria grown in BHIS medium. Different dilutions of the test compounds in the absence of bacteria were used to measure background signals.

Crystal violet (CV) staining of biofilms

To quantify the resulting biofilm biomass, the washed biofilms were stained with 200 μl of a 0.1% crystal violet solution (1:4 dilution in DDW of the Gram's crystal violet solution, Merck) for 20 min at room temperature [24]. Thereafter the biofilms were washed twice with DDW and the stain dissolved in 200 μl of a 33% acetic acid solution. The OD at 595 nm was measured spectrophotometrically using the M200 Tecan microplate reader. Different dilutions of the test compounds in the absence of bacteria were used to measure background signals.

Metabolic activity of the biofilms

The metabolic activity of the biofilms was examined using the MTT assay [25]. In brief, 50 μl of a 0.5 mg/ml (1.2 mM) solution of MTT (3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide) (Sigma, USA) was added to the biofilms, and after an 1 h incubation, 150 μl of PBS was added, the supernatant discarded, and the tetrazolium formed within the biofilms dissolved in 200 μl of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The OD at 570 nm was measured spectrophotometrically using the M200 Tecan microplate reader. Different dilutions of the test compounds in the absence of bacteria were used to measure background signals.

FilmTracer™ SYPRO® Ruby biofilm matrix stain

The biofilm biomass was also measured using the FilmTracer™ SYPRO® Ruby biofilm matrix stain (Invitrogen, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). The washed biofilms were incubated with 100 μl of the reagent for 30 min at room temperature, followed by several washes with DDW. Thereafter the fluorescence of the biofilms was measured in the M200 Tecan microplate reader with excitation at 450 nm and emission at 610 nm.

Confocal laser scanning microscope (CLSM)

The biofilms were stained with the SYTO 9/propidium iodide (PI) Live/Dead BacLight viability kit (Molecular Probes, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, California, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions [26]. The SYTO 9 green fluorescence dye, which enters both live and dead bacteria, was visualized using 488 nm excitation and 515 nm emission filters. The PI red fluorescence dye, which only penetrates dead bacteria, was measured using 543 nm excitation and 570 nm emission filters. Thus, live bacteria fluoresce green light, while dead bacteria fluoresce both green and red light. The samples were visualized for thickness and bacterial vitality using the Nikon Yokogawa W1 Spinning Disk Microscope with 50 μm pinholes. The biofilm depth was assessed by capturing optical cross-sections at 2.5 μm intervals from the bottom of the biofilm to its top. Three-dimensional images of the formed biofilms were constructed using the NIS-Element AR software. This software was also used to analyze the fluorescence intensity of SYTO 9 and PI staining in each captured layers of the biofilms. The biofilms of treated bacteria were compared to control untreated bacteria.

High resolution scanning electron microscope (HR-SEM)

Untreated and treated biofilms were fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde in DDW for 20 min, washed in DDW, air-dried, gold-coated and visualized using an analytical Quanta 200 Environmental High-Resolution Scanning Electron Microscope (EHRSEM) (FEI, Eindhoven, The Netherlands). The biofilm structure was observed in different regions, each with increasing magnifications.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in triplicates and repeated three times. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student t-test using the excel Microsoft software. Statistically significance was determined when the p value was less than 0.05.

Results

The diluted CPP-ACP tooth mousse (GC) did not inhibit planktonic growth of S. mutans

Our first question was whether the CPP-ACP-containing tooth mousse affects the planktonic growth of the cariogenic S. mutans. To this end, we incubated the bacteria with different dilutions of the tooth mousse for 24 h, and analyzed the bacteria viability using the BacTiter-Glo™ kit that measures the ATP content. Surprisingly, we observed that the diluted tooth mousse increased the ATP content in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1a). The diluted tooth mousse without bacteria gave only a relatively low signal with the reagent, suggesting that the luminescence originates from the bacteria in the sample. It could be that some of the ATP detected is due to ATP released from the bacteria that is retained by components of the tooth mousse. To figure out whether there is a true increase in the bacterial number, we determined the colony forming units (CFUs) in each of the samples. Indeed, we found a 1.4–3.3-fold increase in the bacterial count when S. mutans was exposed to 3–50 mg/ml GC tooth mousse (Fig. 1b). Similarly, we found an increase in the ATP content when using different dilutions of the CPP-ACPF tooth mousse (GCP) (Fig. 1a). When counting the live bacteria using the CFU assay, we noticed a 1.5–2.3-fold increase in the bacterial number with 3–12.5 mg/ml GCP, while 25–50 mg/ml GCP resulted in a 40–60% reduction in the viable bacteria after a 24 h incubation (Fig. 1b).

The effect of GC and GCP on planktonic growth of S. mutans. a The ATP content of S. mutans that have grown in the presence of various concentrations of suspended GC or GCP tooth mousse for 24 h. n = 3. b The CFU of S. mutans that have grown in the presence of various concentrations of suspended GC or GCP tooth mousse for 24 h. n = 3. * p < 0.05 in comparison to untreated bacteria

Since CPP is a tryptic digest of the milk protein casein and is composed of peptides and phosphate groups, it is likely that CPP might be a nutrient for S. mutans. To study this possibility, the bacteria were exposed to increasing concentrations of CPP, and the planktonic growth and ATP content were analyzed after 6 and 24 h (Additional file 1: Fig. S1). We observed that CPP treatment did not lead to an increased bacterial growth after 6 h, but caused a significant increase in the ATP content at doses of 5–50 mg/ml (Additional file 1: Fig. S1A). After 24 h incubation, there was 1.5-time more bacteria in samples treated with 10–50 mg/ml CPP than in control samples (Additional file 1: Fig. S1B). Again, we observed that CPP increases the ATP content per bacterium at concentrations 10–50 mg/ml when compared to control bacteria (Additional file 1: Fig. S1B). Thus, CPP may contribute to the increase in ATP content in bacteria exposed to GC and GCP tooth mousse, but it is likely that other components of the tooth mousse contribute to the increased proliferation of S. mutans.

Both GC and GCP exerted strong anti-biofilm effects on S. mutans

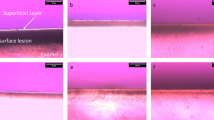

We next examined the effect of GC and GCP on S. mutans biofilm formation. For this purpose, S. mutans was allowed to form biofilm in the presence of various dilutions of the tooth mousse, and the extent of biofilm formation was assayed after 4 h and 24 h. Already after 4 h, a dose-dependent reduction in the biofilm was observed as measured by the MTT metabolic assay (Fig. 2a). MBIC90 was 12.5 and 6.5 mg/ml for GC and GCP, respectively (Fig. 2a). Also, strong reduction of biofilm mass was observed after 24 h incubation with GC or GCP (Fig. 2b–d; Additional file 1: Fig. S2). The metabolic activity of the biofilms was reduced by 80% when exposed to 6.25 mg/ml of either GC or GCP (Fig. 2b). At the lower concentrations of 1.56 and 3.125 mg/ml, GCP reduced the metabolic activity of the biofilms by 50%, while GC had only a minor effect (Fig. 2b). When examining the biofilm biomass with crystal violet, a significant reduction of 60–80% in the biomass was observed at 12.5–50 mg/ml (Fig. 2c). In line with these findings, the FilmTracer™ SYPRO® Ruby biofilm matrix stain showed a dose-dependent reduction in the extracellular biofilm matrix (Fig. 2d). Again, GCP was more efficient than GC (Fig. 2d). The strong anti-biofilm effect of GC and GCP was further confirmed by confocal laser scanning microscopy using the live/dead BacLight viability kit (Fig. 3). GC and GCP at 5 mg/ml reduced the number of bacteria in the biofilm by 95–99% (Figs. 3d–f and g-i versus 3a–c; Fig. 4a, b). Also, the depth of the biofilm was reduced from 125–135 µm in control samples to 50–65 µm in samples exposed to GC or GCP (Figs. 3 and 4). The percentage of PI-positive bacteria dropped from 21.1 ± 4.3% in control samples to 9.8 ± 3.2% and 6.16 ± 1.2% in biofilms treated with GC and GCP, respectively (Fig. 4c–e). Altogether, our data suggest that the anti-biofilm effect is not due to killing of the bacteria, but rather a prevention of their adherence to the surface.

Anti-biofilm effect of GC and GCP on S. mutans. a Metabolic activity in S. mutans biofilms formed for 4 h in the presence of various concentrations of suspended GC or GCP tooth mousse as determined by the MTT assay. n = 3. b Metabolic activity in S. mutans biofilms formed for 24 h in the presence of various concentrations of suspended GC or GCP tooth mousse as determined by the MTT assay. n = 3. c Crystal violet staining of S. mutans biofilms formed for 24 h in the presence of various concentrations of suspended GC or GCP tooth mousse. n = 3. d FilmTracer™ SYPRO® Ruby biofilm matrix staining of S. mutans biofilms formed for 24 h in the presence of various concentrations of suspended GC or GCP tooth mousse. n = 3. * p < 0.05 in comparison to untreated bacteria

CLSM images of SYTO 9/PI-stained biofilms. Biofilms formed in the absence (a–c) or presence of 5 mg/ml GC (d–f) or GCP (g–i) for 24 h were washed in PBS and stained with SYTO 9 (green fluorescence) and PI (red fluorescence). The images are three-dimensional reconstructions of all layers captured using the NIS Element software. a, d, g are merged images of SYTO 9/PI. b, e, h are SYTO 9 staining. c, f, i are PI staining

Quantification of the SYTO 9/PI staining of biofilms formed in the absence or presence of GC or GCP using the NIS Element Software. The average of calculations done on 4 different biofilms of each treatment group is presented. a Comparison of SYTO 9 staining of Control (black graph) versus GC (blue graph) and GCP (reddish brown graph)-treated biofilms. b Comparison of PI staining of Control (black graph) versus GC (blue graph) and GCP (reddish brown graph)-treated biofilms. c–e The comparison of SYTO 9 (green graph) and PI (red graph) staining of each treatment group. c Control biofilms. d GC-treated biofilms. e GCP-treated biofilms

GC- and GCP-treatment result in altered morphology of S. mutans

We next wanted to find out whether GC and GCP affect the morphology of the bacteria retained in the biofilms. For this purpose, biofilms formed in the presence of 5 mg/ml GC or GCP were inspected under a high-resolution-scanning electron microscope (HR-SEM) (Fig. 5). The control biofilm shows clusters and chains of bacteria embedded in extracellular matrix (Fig. 5a, d). The control bacteria appear as the classical S. mutans that show longer length than width (Fig. 5a, d) [27]. The bacteria in the biofilms of the GC- and GCP-treated samples are enwrapped in a precipitate of components likely from the tooth mousse that have adhered to the biofilm (Fig. 5b-c, e, f). The deposits resemble the structure of sol–gel-deposited calcium phosphate microstructures shown by Fotovvati et al. [28]. The bacteria in the treated biofilms appear shorter and have a more rounded up morphology (Fig. 5b, c, e, f). Systematic measurements of one hundred bacteria from five different images for each treatment group show that the length of the bacteria in the GC- and GCP-treated group was shortened by 25–30% (Fig. 6; p < 0.01).

GC and GCP caused a reduction in the bacterial length of S. mutans. The length of around 100 bacteria were measured in 5 independent HR-SEM images of each treatment group presented in Fig. 5. * p < 0.05 in comparison to untreated bacteria

Discussion

Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate (CPP-ACP) is a compound developed for the prevention of dental caries. This milk-derived agent enables remineralization and prevents demineralization as well as caries by generating a Ca/P reservoir on the teeth [22]. Additionally, CPP-ACP adheres to the salivary pellicle and thus may reduce the attachment of S. mutans [29, 30]. Based on these findings, these compounds have been incorporated into pastes and varnishes [31, 32]. Application of CPP-ACP paste in addition to regular oral hygiene protocol reduced demineralization (white spot lesions) in clinical studies [32,33,34].

Although several studies have examined the remineralization ability of CPP-ACP [16, 33, 34], only a few ones have assessed its anti-bacterial and anti-biofilm effectiveness [35,36,37,38]. In our study, we used various in vitro methods to explore the possible anti-bacterial/anti-biofilm properties of this compound toward the cariogenic S. mutans.

Our results demonstrate that GC tooth mousse containing CPP-ACP does not inhibit planktonic growth of S. mutans at any of the concentrations tested, and even enhanced the number of viable bacteria after a 24 h incubation. The simultaneous presence of fluoride ions in the GCP tooth mousse showed a similar growth-stimulating effect at higher dilutions (0.3–1.25%), while at lower dilutions (2.5–5%), a 40–60% reduction in the viable bacteria was seen that seemingly is due to the fluoride ions known to exert anti-microbial activities [39]. An interesting observation was the dose-dependent elevation in ATP content in the bacterial samples grown with increasing doses of GC and GCP. The relative increase in ATP content was higher than the relative number of live bacteria after a 24 h incubation, suggesting that components in the tooth mousse may affect the metabolism of S. mutans, resulting in elevated ATP production. We suspected that CPP could be the component, since it is composed of peptides and phosphate groups, which can be utilized by the bacteria as nutrition. Indeed, we observed that CPP significantly increased the ATP content of the bacteria, with only minor effect on the planktonic growth. It is likely that other components of the tooth mousse are responsible for the increased proliferation of S. mutans. It is notably that the increase in ATP content by CPP was modest (1.5–3 fold) in comparison to the extreme increase in ATP content (25–40-fold) in samples exposed to GC/GCP. One possibility for the high ATP content detected in the latter samples could be the binding of ATP released from the bacteria to the tooth mousse texture.

Importantly, both GC and GCP showed strong anti-biofilm activities even at high dilutions of more than 1 to a hundred, as demonstrated by reduced number of viable bacteria visualized by CLSM, reduced metabolic activity according to the MTT assay, and reduced crystal violet and SYPRO Ruby staining of the resulting biofilms. This finding accords with the study conducted by Dashper et al. [40], demonstrating that incorporation of 3% CPP-ACP into glass ionomer cements significantly reduced S. mutans biofilm development. We used a different biofilm model where the S. mutans was exposed to CPP-ACP-containing tooth mousse in suspension. Also, in this setting the CPP-ACP prevented the adhesion of S. mutans to the surface. Rahiotis et al. [36] applied the GC tooth mousse on orthodontic retainers and observed a delay in the biofilm formation in the presence of CPP-ACP. They further showed that CPP-ACP favored the nucleation and crystallization of calcium phosphates in the matured biofilms. Our SEM study show that both GC and GCP caused a deposit in the interspaces between the immobilized bacteria in the biofilm that resembles structures of calcium phosphate microcrystals [28]. This deposit barely adhered to the surface of the bacteria, suggesting that it causes unfavorable binding sites for the bacteria. The presence of this deposit on the surface might thus be a mechanism for preventing bacterial biofilm development. An anti-adhesion mechanism of CPP-ACP has also been proposed by Philip and Walsh [32]. Another interesting notation taken from the SEM images is the appearance of smaller and more rounded bacteria in the GC- and GCP-treated samples. The more rounded structure of the bacteria in the presence of the tooth mousse may be related to their reduced adherence to the surface, which is in contrast to the control bacteria that can spread on the surface. Actively dividing cells often show a more rounded morphology [41], such that the higher proliferation of S. mutans observed in the presence of GC/GCP might contribute to the altered morphology. A septum can be seen in many of the GC- and GCP-treated bacteria, suggesting that the bacteria are in division. The live/dead staining show that most of the GC and GCP-treated bacteria in the biofilms are alive (91–94%), which is in accordance with our finding that these compounds are not bacteriocidic. GCP that also contains fluoride, was more efficient than GC in preventing biofilm development, which can be explained by the contributing role of the fluoride ion in reducing biofilm formation of S. mutans [42]. Altogether, our data demonstrate that the GC and GCP tooth mousse prevent the adherence and biofilm development of the oral cariogenic S. mutans.

Conclusions

Dentists and orthodontists seek to maintain good oral hygiene in their patients. Clinical trials show that the status of oral hygiene is enhanced once anti-bacterial mouth rinses are given as part of the oral hygiene protocol [43, 44]. The results of the present study suggest that CPP-ACP-containing products, in the form of mouthwash, could provide an anti-cariogenic effect based on the strong anti-biofilm activity against S. mutans. Such biofilm inhibition strategies are proposed to be suitable for orthodontic pediatric patients and for dental patients in general. It should, however, be kept in mind that dental caries might also be caused by other microbes besides S. mutans [3], and the efficacy of the CPP-ACP-containing products on preventing biofilm formation of these organisms needs to be proved. Further studies are required to demonstrate the microbial spectrum affected by CPP-ACP.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used during the present study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ATP:

-

Adenosine triphosphate

- CFU:

-

Colony forming unit

- CLSM:

-

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

- CPP-ACP:

-

Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate

- CV:

-

Crystal violet

- DDW:

-

Doubled distilled water

- GC:

-

GC tooth mousse containing CPP-ACP

- GCP:

-

GC plus tooth mousse containing CPP-ACP and fluoride

- MBIC:

-

Minimum biofilm inhibitory concentration

- MTT:

-

3-(4,5-Dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl-2H-tetrazolium bromide

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- HR-SEM:

-

High resolution scanning electron microscope

References

Bowen WH, Burne RA, Wu H, Koo H. Oral biofilms: pathogens, matrix, and polymicrobial interactions in microenvironments. Trends Microbiol. 2018;26:229–42.

Beikler T, Flemmig TF. Oral biofilm-associated diseases: trends and implications for quality of life, systemic health and expenditures. Periodontol. 2011;2000(55):87–103.

Chen X, Daliri EB, Kim N, Kim JR, Yoo D, Oh DH. Microbial etiology and prevention of dental caries: exploiting natural products to inhibit cariogenic biofilms. Pathogens. 2020;9:569.

Lemos JA, Palmer SR, Zeng L, Wen ZT, Kajfasz JK, Freires IA, Abranches J, Brady LJ. The biology of Streptococcus mutans. Microbiol Spectr. 2019;7(10):1128.

Matsumoto-Nakano M. Role of Streptococcus mutans surface proteins for biofilm formation. Jpn Dent Sci Rev. 2018;54:22–9.

Krzyściak W, Jurczak A, Kościelniak D, Bystrowska B, Skalniak A. The virulence of Streptococcus mutans and the ability to form biofilms. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;33:499–515.

Shemesh M, Tam A, Steinberg D. Differential gene expression profiling of Streptococcus mutans cultured under biofilm and planktonic conditions. Microbiology. 2007;153:1307–17.

Al Mulla AH, Kharsa SA, Kjellberg H, Birkhed D. Caries risk profiles in orthodontic patients at follow-up using cariogram. Angle Orthod. 2009;79:323–30.

Mei L, Chieng J, Wong C, Benic G, Farella M. Factors affecting dental biofilm in patients wearing fixed orthodontic appliances. Prog Orthod. 2017;18:4.

Perkowski K, Baltaza W, Conn DB, Marczyńska-Stolarek M, Chomicz L. Examination of oral biofilm microbiota in patients using fixed orthodontic appliances in order to prevent risk factors for health complications. Ann Agric Environ Med. 2019;26:231–5.

Ren Y, Jongsma MA, Mei L, van der Mei HC, Busscher HJ. Orthodontic treatment with fixed appliances and biofilm formation-a potential public health threat? Clin Oral Investig. 2014;18:1711–8.

Reynolds EC. Anticariogenic complexes of amorphous calcium phosphate stabilized by casein phosphopeptides: a review. Spec Care Dentist. 1998;18:8–16.

Reema SD, Lahiri PK, Roy SS. Review of casein phosphopeptides-amorphous calcium phosphate. Chin J Dent Res. 2014;17:7–14.

Walker G, Cai F, Shen P, Reynolds C, Ward B, Fone C, Honda S, Koganei M, Oda M, Reynolds E. Increased remineralization of tooth enamel by milk containing added casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. J Dairy Res. 2006;73:74–8.

Ferrazzano GF, Amato I, Cantile T, Sangianantoni G, Ingenito A. In vivo remineralising effect of GC tooth mousse on early dental enamel lesions: Sem analysis. Int Dent J. 2011;61:210–6.

Llena C, Leyda AM, Forner L. CPP-ACP and CPP-ACPF versus fluoride varnish in remineralisation of early caries lesions. A prospective study. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2015;16:181–6.

Ma X, Lin X, Zhong T, Xie F. Evaluation of the efficacy of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate on remineralization of white spot lesions in vitro and clinical research: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2019;19:295.

Reynolds EC, Cai F, Cochrane NJ, Shen P, Walker GD, Morgan MV, Reynolds C. Fluoride and casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. J Dent Res. 2008;87:344–8.

Oliveira GM, Ritter AV, Heymann HO, Swift E Jr, Donovan T, Brock G, Wright T. Remineralization effect of CPP-ACP and fluoride for white spot lesions in vitro. J Dent. 2014;42:1592–602.

Cai F, Shen P, Morgan MV, Reynolds EC. Remineralization of enamel subsurface lesions in situ by sugar-free lozenges containing casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate. Aust Dent J. 2003;48:240–3.

Madrid-Troconis CC, Perez-Puello S.d.C. . Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate nanocomplex (CPP-ACP) in dentistry: State of the art. Revista Facultad de Odontología Universidad de Antioquia. 2019;30:248–62.

Reynolds EC. Calcium phosphate-based remineralization systems: scientific evidence? Aust Dent J. 2008;53:268–73.

Simmer JP, Hardy NC, Chinoy AF, Bartlett JD, Hu JC. How fluoride protects dental enamel from demineralization. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2020;10:134–41.

Farkash Y, Feldman M, Ginsburg I, Steinberg D, Shalish M. Polyphenols inhibit Candida albicans and Streptococcus mutans biofilm formation. Dent J (Basel). 2019;7:42.

Feldman M, Ginsburg I, Al-Quntar A, Steinberg D. Thiazolidinedione-8 alters symbiotic relationship in C. albicans-S. mutans dual species biofilm. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:140.

Duanis-Assaf D, Kenan E, Sionov R, Steinberg D, Shemesh M. Proteolytic activity of Bacillus subtilis upon κ-casein undermines its “caries-safe” effect. Microorganisms. 2020;8:221.

Xiang Z, Li Z, Ren Z, Zeng J, Peng X, Li Y, Li J. EzrA, a cell shape regulator contributing to biofilm formation and competitiveness in Streptococcus mutans. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2019;34:194–208.

Fotovvati B, Namdari N, Dehghanghadikolaei A. On coating techniques for surface protection: a review. J Manuf Mater Process. 2019;3:28.

Reynolds EC. Remineralization of enamel subsurface lesions by casein phosphopeptide-stabilized calcium phosphate solutions. J Dent Res. 1997;76:1587–95.

Reynolds EC, Cai F, Shen P, Walker GD. Retention in plaque and remineralization of enamel lesions by various forms of calcium in a mouthrinse or sugar-free chewing gum. J Dent Res. 2003;82:206–11.

Attiguppe P, Malik N, Ballal S, Naik SV. CPP-ACP and fluoride: a synergism to combat caries. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2019;12:120–5.

Philip N, Walsh L. The potential ecological effects of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate in dental caries prevention. Aust Dent J. 2019;64:66–71.

Memarpour M, Fakhraei E, Dadaein S, Vossoughi M. Efficacy of fluoride varnish and casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate for remineralization of primary teeth: a randomized clinical trial. Med Princ Pract. 2015;24:231–7.

Güçlü ZA, Alaçam A, Coleman NJ. Corrigendum to “a 12-week assessment of the treatment of white spot lesions with CPP-ACP paste and/or fluoride varnish.” Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1816959.

Dashper SG, Shen P, Sim CPC, Liu SW, Butler CA, Mitchell HL, D’Cruze T, Yuan Y, Hoffmann B, Walker GD, Catmull DV, Reynolds C, Reynolds EC. CPP-ACP promotes snf(2) efficacy in a polymicrobial caries model. J Dent Res. 2019;98:218–24.

Rahiotis C, Vougiouklakis G, Eliades G. Characterization of oral films formed in the presence of a CPP-ACP agent: an in situ study. J Dent. 2008;36:272–80.

Philip N, Leishman SJ, Bandara H, Walsh LJ. Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate attenuates virulence and modulates microbial ecology of saliva-derived polymicrobial biofilms. Caries Res. 2019;53:643–9.

Alawadhi NB, Lippert F, Gregory RL. Effects of casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate crème on nicotine-induced Streptococcus mutans biofilm in vitro. Clin Oral Investig. 2020;24:3513–8.

Liao Y, Brandt BW, Li J, Crielaard W, Van Loveren C, Deng DM. Fluoride resistance in Streptococcus mutans: a mini review. J Oral Microbiol. 2017;9:1344509.

Dashper SG, Catmull DV, Liu SW, Myroforidis H, Zalizniak I, Palamara JE, Huq NL, Reynolds EC. Casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate reduces streptococcus mutans biofilm development on glass ionomer cement and disrupts established biofilms. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0162322.

Melaugh G, Hutchison J, Kragh KN, Irie Y, Roberts A, Bjarnsholt T, Diggle SP, Gordon VD, Allen RJ. Shaping the growth behaviour of biofilms initiated from bacterial aggregates. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149683.

Nassar HM, Gregory RL. Biofilm sensitivity of seven Streptococcus mutans strains to different fluoride levels. J Oral Microbiol. 2017;9:1328265.

Erbe C, Klukowska M, Timm HC, Barker ML, van der Wielen J, Wehrbein H. A randomized controlled trial of a power brush/irrigator/mouthrinse routine on plaque and gingivitis reduction in orthodontic patients. Angle Orthod. 2019;89:378–84.

Niazi FH, Kamran MA, Naseem M, AlShahrani I, Fraz TR, Hosein M. Anti-plaque efficacy of herbal mouthwashes compared to synthetic mouthwashes in patients undergoing orthodontic treatment: a randomised controlled trial. Oral Health Prev Dent. 2018;16:409–16.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Vitaly Gutkin at the The Harvey M. Krueger Family Center for Nanoscience and Nanotechnology at the Edmond J. Safra Campus of The Hebrew University of Jerusalem for his valuable assistance in conducting the HR-SEM experiments, and Dr. Yael Feinstein-Rotkopf at the Core Research Facility of The Hadassah Medical School for her valuable assistance in conducting the CLSM experiments. This study is part of the M.Sc. thesis of Danae Tsavdaridou. Prof. D. Steinberg holds the H. Leslie Levine Chair in Oral Pathology and Dental Medicine.

Funding

The authors want to thank Dr. Max Florence − Canada Endowment for partial support of the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RVS, DT and MA performed the experiments. RVS and DT designed the experiments, analyzed the data, interpreted the data, prepared the figures, and wrote the manuscript. BZ, DS and MS supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent for Publication

Not applicable

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Supplementary Data.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sionov, R.V., Tsavdaridou, D., Aqawi, M. et al. Tooth mousse containing casein phosphopeptide-amorphous calcium phosphate prevents biofilm formation of Streptococcus mutans. BMC Oral Health 21, 136 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01502-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12903-021-01502-6