Abstract

Background

The pineal lesion affecting melatonin is a rare cause of central precocious puberty by decreasing the inhibition of hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis. Germ cell tumor secreting human chorionic gonadotropin is a rare cause of peripheral puberty.

Case presentation

A 5.8-year-old male presented facial hair and phallic growth, deepened voice, and accelerated growth velocity for 6 months. The elevated human chorionic gonadotropin level with undetectable gonadotropin levels indicated peripheral precocious puberty. Brain imaging revealed a pineal mass and further pathology indicated the diagnosis of teratoma. During chemoradiotherapy with operation, the elevated human chorionic gonadotropin level reduced to normal range, while the levels of gonadotropins and testosterone increased. Subsequently, progressing precocious puberty was arrested with gonadotrophin-releasing hormone analog therapy. Previous cases of transition from peripheral precocious puberty to central precocious puberty were reviewed. The transitions were caused by the suddenly reduced feedback inhibition of sex steroid hormones on gonadotropin releasing hormone and gonadotropins.

Conclusions

For patients with human chorionic gonadotropin-secreting tumors, gonadotropin levels increase prior to sex steroid decrease, seems a sign of melatonin-related central PP related to melatonin.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Central nervous system neoplasm is considered as one of the important etiologies of precocious puberty (PP). The neoplasm in proximity to the hypothalamic-pituitary region or intracranial radiotherapy focused on this region [1] may activate the gonadotrophin releasing hormone (GnRH) neuron in advance, causing central PP. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) secreted by tumors may mimic luteinizing hormone (LH) to promote the excessively sex steroid production, causing peripheral PP. In addition, human reproductive cycles are regulated by melatonin, a central gonadal inhibition hormone secreted from the pineal gland [2,3,4]. The pineal lesion could impact the structure and function of pineal gland, potentially affecting the level of melatonin and then causing central PP [5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13]. Consequently, pineal tumors may present PP via either damging the regulation of pineal and melatonin or mimicking LH funcion by circulating hCG. However, only cases of peripheral PP due to pineal germ cell tumors have been reported to date. The transition from peripheral to central PP is often seen after treatment of the underlying cause. Currently, the loss of feedback inhibition on the hypothalamus and pituitary has been demonstrated as a crucial trigger. Primary gonadal or adrenal diseases which featured elevated sex steroid levels are the most common causes of such loss. In addition, maturation of the HPG axis after prolonged exposure to the elevated sex steroids is believed to be a contributing factor. However, it is unclear whether there are other mechanisms that induce peripheral PP progress to central PP. Herein, we proposed that the pineal hCG-secreting tumor that occurs prior to the expected or normal pubertal onset age may also induce this transition. To further discuss the underlying mechanism, reported cases of central PP secondary to peripheral PP with available data were also reviewed and summarized.

Case presentation

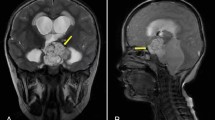

A 5.8-year-old boy was admitted to our hospital with a 6-month of facial hair and phallic growth, deepen voice and accelerate growth velocity. The Tanner stage was II for genital development and II-III for pubic hair. Both side testicular volumes were 4 mLby Prader. Family history of PP was denied. The serum sex hormone profile indicated prepubertal levels of gonadotropins with basal LH < 0.1IU/L (prepubertal range < 0.1–0.3 IU/L) and basal FSH < below 0.1 IU/L (prepubertal range < 0.1-3), and pubertal testosterone level (4.48 ng/ml, prepubertal: <0.2-1ng/mL). His height reached 129 cm (+ 2.4 standard deviation scores,) with a high serum insulin like growth factor-1 level (+ 3.5 standard deviation scores) in National-specific charts [14]. Other anterior pituitary hormonal profiles were normal. HCG was detectable both in serum and in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), 7.12 and 15.66 IU/L separately. Bone age (BA) was advanced to 8 years old. Contrast-enhanced brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a homogeneously enhanced pineal mass (Fig. 1A). The elevated serum hCG level and pineal mass on imaging suggested the clinicial diagnosis of intracranial germ cell tumor (iGCT) and then two courses of ICE chemotherapy (ifosfamide, carboplatin and etoposide) were performed. Repeated MRI did not reflect a significant shrinkage of the pineal lesion (Fig. 1B) although hCG (< 0.1 IU/L, range 0-2.6 IU/L) has been normalized. Meanwhile, basal serum gonadotropin levels (LH 2.96 and FSH 1.86 IU/L, separately) unexpectedly increased (Fig. 2). Considering the possibility of mixed germ cell tumor due to elevated hCG level and poor response to chemotherapy [15, 16], the patient underwent a neurosurgical operation and the histological result revealed a mature teratoma. Subsequently, he continued to receive two additional courses of ICE chemotherapy and the radiotherapy targeting the whole brain (24 Gy) plus the pineal region boosting (12 Gy). During this period, his gonadotropin and testosterone levels were within the normal pubertal range, although with a transient change (Fig. 2). After operation and chemoradiotherapy, MRI indicated the morphological disorders of the pineal gland without an enhanced lesion (Fig. 1C). The patient’s puberty progressed with the Tanner stage III for genital development and stage III for pubic hair. Meanwhile, the patient’s height reached 134 cm (+ 2.7SD) with a bone age of 12 years. To postpone epiphyseal closure and save growth potential, GnRH analogue therapy was started to suppress gonadal activation. This boy decided to return to the local hospital to continue GnRH analogs therapy. Through telephone survey after 2 months of GnRH analogue therapy, the patient’s gonadotropin levels normalized (LH 0.29 and the FSH 0.13 IU/L) and premature presentations gradually regressed. After 18 months of regular GnRH analogue therapy, the patient’s LH and FSH remained undetectable while his precocious puberty regressed. The growth velocity is approximately 5 cm per year.

Contrast-enhanced brain MRI. (A) Sagittal contrast-enhanced brain MRI at diagnosis, (B) sagittal contrast-enhanced brain MRI after 2 courses of chemotherapy, (C) sagittal contrast-enhanced brain MRI after chemoradiotherapy with additional neurosurgical operation.1A showed a homogenously enhancing pineal mass (marked in white arrow); 1B showed the similar tumor imaging (marked in white arrow) to 1A although a mild shrinkage; 1C showed a disorder of pineal structure (marked in white arrow)

Gonadal hormone profile and hCG concentration. According to the therapeutic strategy, the PP of this patient could be divided into GnRH-independent stage (marked in pink box), GnRH dependent stage (marked in yellow box) and the transient stage (marked in the overlap of two boxes). hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, follicle stimulating hormone; T, testosterone; ICE, ifosfamide,carboplatin and etoposide; WRBT, whole brain radiation therapy

Review of literature

We systematically searched PubMed database with “central PP” and “peripheral PP” from inception through July 1st, 2022. No language restrictions were imposed. A hand search through reference lists of relevant primary and review articles was also performed for completeness. Each of the two review authors (HC and C-Y M) independently screened articles for inclusion based on title and abstract and reviewed relevant articles as full text. Disagreement during the review process was resolved by consensus through involvement of a third review author (L-Y Z). A total of 25 original articles involving 51 patients with the transition from peripheral to central PP were reviewed and summarized (16–41) (Table 1). Most of the patients were male (M:F = 11:6), with a CA range of 2–9 years and approximate BA advancement of 1–6 years. All patients had significantly elevated sex steroid levels, with testosterone levels ranging from 196 to 625 ng/dl in males and estradiol levels ranging from 20 to 90 pg/ml in females. Twenty-one patients developed peripheral PP due to congenital adrenal hyperplasia (11 males and 10 females). On admission, CA range and approximate BA advancement range were 3–8 years and 3–16 years, respectively, with symptom intervals ranging from 3 to 14 months. Central PP occurred approximately 6–36 months after the replacement of glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Twelve patients developed peripheral PP due to adrenal tumor (7 males and 5 females). On admission, CA range and approximate BA advancement range were 4.5-8 years and 1.5-6 years, respectively, with symptom intervals ranging from 3 to 36 months. Central PP occurred approximately 2–6 months after adrenalectomy for adrenal tumor. Ten patients developed peripheral PP due to the gonadal tumors, including 8 males with Leydig cell tumors and two females with ovary granulosa cell tumors. On admission, CA range and approximate BA advancement range were 5–9 years and 2–6 years, respectively, with the symptom intervals ranging from 6 to 36 months. Central PP occurred approximately 3–18 months after the surgery for tumors. Five male patients developed peripheral PP due to familial male-limited PP. On admission, CA range and approximate BA advancement range were 2–7 years and 3–5 years, respectively. One patient had a symptom interval of 36 months, while the others’ were unclear. Antiandrogen drugs were supplied. Central PP occurred 18 months after antiandrogen treatment in one patient and the duration from peripheral PP to central PP of other patients were unclear. The other patients developed peripheral PP due to McCune-Albright and then progressed to central PP without further details. Only one 6-years old boy with pineal teratoma development peripheral PP and developed central PP at 8 years old, 8 months after his surgery for tumors. Except one male patient received cyproterone acetate, all patients arrested their central PP by GnRH analogues.

Discussion

Transition from peripheral PP to central PP is rare, which means activating GnRH or inhibiting gonadotropin inhibitory hormone after a period of overexposure to steroids. This transition has been reported in patients with Leydig cell tumors [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24], adrenal tumors [25,26,27,28,29,30,31], congenital adrenal hyperplasia [32,33,34,35], overy granulosa cell tumors [36,37,38], familial male-limited PP [39, 40], McCune-Albright syndrome [41] and pineal mature teratoma [42], probably due to the circulating sex steroid hormones’ suddenly reduced feedback inhibition on gonadotropin releasing hormone and gonadotropins. In addition to primary gonadal diseases, only one case of central PP secondary to extragonadal hCG-secreting iGCT has been reported, and this patient has long-term exposure to endogenous testosterone [42].

In the present study, we describe a young boy with a pineal germ cell tumor and peripheral PP who later developed central PP. Initial peripheral PP of the patient due to serum hCG, which binds to the LH receptor and then acts on the testicular Leydig cell to excessively promote testosterone synthesis. The elevated hCG level in serum and CSF inidicated the diagnosis of iGCT. The residual in pineal lesion after induction chemotherapy indicated the diagnosis of mixed iGCT and following histological results indicated the teratoma component. During the initial 2 courses of chemotherapy, although the hCG level returned to normal range, the patient’s LH and FSH levels increased synchronously with the stably elevated testosterone. Compared to previous cases where patients’ central PP commonly developed after months or even years of peripheral PP regression, the abnormal change in gonadotropin and sex steroid hormone of this patient suggested a probable mechanism different from loss of negative feedback to the gonadotropins (Fig. 3). In our opinion, the transition from peripheral PP to central PP in the present study is likely associated with the destruction of the pineal gland and the impairment of melatonin function (1). Patient’s gonadotropin levels began to increase following the chemotherapy in parallel with a decline of hCG and sex steroid level. The change in the level of circulating sex steroids seems insufficient to regulate hythalamic inhibition during this short peroid (2). The patient received surgery and multidrug therapy for tumor at the age of 5. During this period, the inhibitory role of melatonin in gonadotropin release was usually strong and crucial [43]. The annual rhythm of melatonin during this period may act as a regulator of pubertal onset (3). Most of the published cases of transition from peripheral PP to central PP are adrenal or gonadal diseases, rather than extragonadal diseases. Nevertheless, before central PP activates, adrenal or gonadal diseases manifested long-term and high-level exposure to sex steroid hormone. But for extragonadal diseases, the exposure time is commonly shorter, and level lower. Besides, there was only one case of pineal teratoma that has been reported to developed central PP after peripheral PP. The differences between previous case and oue case are also significant. Firstly, the peak elevated testosterone level in our case seems not high enough to play a crucial role in the hypothalamic threshold. That may be why patients with transition from peripheral to central precocious puberty had adrenal or gonadal disease, or other disease secreting sufficient sex steroid hormone. Additionally, our case developed central precocious puberty immediately after normalizing the hCG, while previous cases always had a time span from peripheral to central precocious puberty. Finally, the symptom interval of the present patient was only six months so that the exposure time is not a long-standing period [4]. Other causes triggering GnRH-dependent puberty, like radiotherapy, co-existence of other lesions in hypothalamus-pituitary region, injury or infection of the central nervous system have been carefully excluded. However, all these presumptions are based on the strong evidence of physiological and the neuroendocrine functions of the pineal gland and melatonin, related to the clinical manifestations and the changes in sex hormones. At present, the clinical assessment of the role of melatonin in precocious puberty remains difficult and thus there is very little data on melatonin levels in peripheral or in the CNS. The difficulties are as follows. First, melatonin samples should be collected under dim light conditions throughout the night after controlling potential risk factors for oxidative stress and inflammation. It seems difficult for malignancy children to collect melatonin sample during their crucial anti-cancer therapies. Next, the reference range of melatonin matched for gender, age, and ethnicity in healthy individuals remain controversial so that interpretation of results may not be straightforward. Finally, in future research, the evaluation in puberty of patients with pineal hCG-secreting tumors should be highlighted, although the hCG-induced PP of most cases would spontaneously regress together with tumor elimination. If possible, collecting the melatonin level at baseline and after therapy should be recommended.

Conclusion

Clinicians caring for young patients with pineal hCG-secreting tumors should be alert to the secondary central PP, although most hCG-induced peripheral PP would regress after the tumor was eliminated. Gonadotropin levels increasing prior to sex steroid suppression may be a a sign of melatonin-related central PP. It is highly recommended to assess the function of hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis by testing hormones during the treatment period of pineal hCG-secreting tumors.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PP:

-

Precocious puberty

- GnRH:

-

Gonadotrophin releasing hormone

- hCG:

-

Human chorionic gonadotropin

- LH:

-

Luteinizing hormone

- FSH:

-

Follicle stimulating hormone

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- iGCT:

-

Intracranial germ cell tumor

- BA:

-

Bone age

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- CA:

-

Chronological age

References

Armstrong GT, Whitton JA, Gajjar A, Kun LE, Chow EJ, Stovall M, et al. Abnormal timing of menarche in survivors of central nervous system tumors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2562–70.

Silman R. Melatonin and the human gonadotrophin-releasing hormone pulse generator. J Endocrinol. 1991;128(1):7–11.

Dragojevic Dikic S, Jovanovic AM, Dikic S, Jovanovic T, Jurisic A, Dobrosavljevic A. Melatonin: a “Higgs boson” in human reproduction. Gynecol Endocrinology: Official J Int Soc Gynecol Endocrinol. 2015;31(2):92–101.

Tsutsui K, Ubuka T, Ukena K. Advancing reproductive neuroendocrinology through research on the regulation of GnIH and on its diverse actions on reproductive physiology and behavior. Front Neuroendocr. 2022;64:100955.

Kornreich L, Horev G, Blaser S, Daneman D, Kauli R, Grunebaum M. Central precocious puberty: evaluation by neuroimaging. Pediatr Radiol. 1995;25(1):7–11.

Franzese A, Buongiovanni C, Belfiore G, Moggio G, Valerio G, Ciccarelli NP, et al. Pineal cyst in a girl with central precocious puberty. Clin Pediatr. 1997;36(9):543–5.

Dickerman RD, Stevens QE, Steide JA, Schneider SJ. Precocious puberty associated with a pineal cyst: is it disinhibition of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis? Neuroendocrinol Lett. 2004;25(3):173–5.

Benítez Fuentes R, de Cuéllar Paracchi MV, Blanco Rodríguez M, Soriano Guillén L. Central precocious puberty and pineal gland cyst: an association or incidental finding? An Pediatr (Barc). 2008;68(1):72–3.

García Amorín Z, Rodríguez Delhi C, Soriano Guillén L, Suárez Tomás JI, Riaño Galán I. [Relationship between pineal cysts and central precocious puberty]. Anales de pediatria (Barcelona, Spain : 2003). 2010;72(6):420–3.

Savas Erdeve S, Ocal G, Berberoglu M, Siklar Z, Hacihamdioglu B, Evliyaoglu O, et al. The endocrine spectrum of intracranial cysts in childhood and review of the literature. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabolism: JPEM. 2011;24(11–12):867–75.

Lacroix-Boudhrioua V, Linglart A, Ancel PY, Falip C, Bougnères PF, Adamsbaum C. Pineal cysts in children. Insights Imaging. 2011;2(6):671–8.

Özcabi B, Akay G, Yesil G, Uyur Yalcin E, Kirmizibekmez H. A case of Sotos syndrome caused by a novel variant in the NSD1 gene: A proposed rationale to treat accompanying precocious puberty. Acta Endocrinol (Bucharest). 2020;16(2):245–9.

Kumar KV, Verma A, Modi KD, Rayudu BR. Precocious puberty and pineal cyst–an uncommon association. Indian Pediatr. 2010;47(2):193–4.

Xu S, Gu X, Pan H, Zhu H, Gong F, Li Y, et al. Reference ranges for serum IGF-1 and IGFBP-3 levels in Chinese children during childhood and adolescence. Endocr J. 2010;57(3):221–8.

Murray MJ, Bartels U, Nishikawa R, Fangusaro J, Matsutani M, Nicholson JC. Consensus on the management of intracranial germ-cell tumours. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):e470–7.

Bowzyk Al-Naeeb A, Murray M, Horan G, Harris F, Kortmann RD, Nicholson J, et al. Current management of intracranial germ cell tumours. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2018;30(4):204–14.

Kiepe D, Richter-Unruh A, Autschbach F, Kessler M, Schenk JP, Bettendorf M. Sexual pseudo-precocity caused by a somatic activating mutation of the LH receptor preceding true sexual precocity. Horm Res. 2008;70(4):249–53.

Lignitz S, Partsch CJ, Wudy SA, Hartmann MF, Pohlenz J. Clinical and metabolic findings in a 6-year-old boy with a Leydig cell tumour. Acta Paediatr. 2011;100(12):e280-2.

Olivier P, Simoneau-Roy J, Francoeur D, Sartelet H, Parma J, Vassart G, et al. Leydig cell tumors in children: contrasting clinical, hormonal, anatomical, and molecular characteristics in boys and girls. J Pediatr. 2012;161(6):1147–52.

Singhania P, Bhattacharjee R, Pratim Chakraborty P, Chowdhury S. Leydig Cell Tumor-Induced Gonadotropin-Independent precocious puberty progressing to Gonadotropin-Dependent precocious puberty Post Orchiectomy: out of the frying Pan into the Fire. Cureus. 2022;14(1):e21165.

Criscuolo T, Sinisi AA, Perrone L, Graziani M, Bellastella A, Faggiano M. Isosexual precocious pseudopuberty secondary to a testosterone-secreting Leydig cell testicular tumour: true isosexual development early after Surgery. Andrologia. 1986;18(2):175–83.

Ghazi AA, Rahimi F, Ahadi MM, Sadeghi-Nejad A. Development of true precocious puberty following treatment of a Leydig cell Tumor of the testis. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabolism: JPEM. 2001;14(9):1679–81.

Santos-Silva R, Bonito-Vítor A, Campos M, Fontoura M. Gonadotropin-dependent precocious puberty in an 8-year-old boy with leydig cell testicular Tumor. Hormone Res Paediatrics. 2014;82(2):133–7.

Verrotti A, Penta L, Zenzeri L, Lucchetti L, Giovenali P, De Feo P. True precocious puberty following treatment of a Leydig Cell Tumor: two case reports and literature review. Front Pead. 2015;3:93.

Ersoy B, Kizilay D, Cayirli H, Temiz P, Gunsar C. Central Precocious Puberty Secondary to Adrenocortical Adenoma in a female child: Case Report and Review of the literature. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30(5):591–4.

Pescovitz OH, Hench K, Green O, Comite F, Loriaux DL, Cutler GB. Jr. Central precocious puberty complicating a virilizing adrenal Tumor: treatment with a long-acting LHRH analog. J Pediatr. 1985;106(4):612–4.

Miyoshi Y, Oue T, Oowari M, Soh H, Tachibana M, Kimura S, et al. A case of pediatric virilizing adrenocortical Tumor resulting in hypothalamic-pituitary activation and central precocious puberty following surgical removal. Endocr J. 2009;56(8):975–82.

Kim MS, Yang EJ, Cho DH, Hwang PH, Lee DY. Virilizing adrenocortical carcinoma advancing to central precocious puberty after Surgery. Korean J Family Med. 2015;36(3):150–3.

Sahana PK, Gopal Sankar KS, Sengupta N, Chattopadhyay K. Boy with central precocious puberty probably due to a peripheral cause. BMJ Case Rep. 2016;6(2):bcr2016214554. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4904404/pdf/bcr-2016-214554.pdf.

Goyal A, Malhotra R, Khadgawat R. Precocious pseudopuberty due to virilising adrenocortical carcinoma progressing to central precocious puberty after surgery. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(3):e229476.

Stecchini MF, Braid Z, More CB, Aragon DC, Castro M, Moreira AC, et al. Gonadotropin-dependent pubertal disorders are common in patients with virilizing adrenocortical tumors in childhood. Endocr Connections. 2019;8(5):579–89.

Pescovitz OH, Comite F, Cassorla F, Dwyer AJ, Poth MA, Sperling MA, et al. True precocious puberty complicating congenital adrenal hyperplasia: treatment with a luteinizing hormone-releasing hormone analog. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984;58(5):857–61.

Bajpai A, Kabra M, Menon PS. Combination growth hormone and gonadotropin releasing hormone analog therapy in 11beta-hydroxylase deficiency. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabolism: JPEM. 2006;19(6):855–7.

Güven A, Nurcan Cebeci A, Hancili S. Gonadotropin releasing hormone analog treatment in children with congenital adrenal hyperplasia complicated by central precocious puberty. Hormones (Athens). 2015;14(2):265–71.

Dayal D, Aggarwal A, Seetharaman K, Muthuvel B. Central precocious puberty complicating congenital adrenal hyperplasia: north Indian experience. Indian J Endocrinol Metabol. 2018;22(6):858–9.

Bas F, Pescovitz OH, Steinmetz R. No activating mutations of FSH receptor in four children with ovarian juvenile granulosa cell tumors and the association of these tumors with central precocious puberty. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2009;22(3):173–9.

Gaikwad PM, Goswami S, Sengupta N, Baidya A, Das N. Transformation of Peripheral sexual precocity to central sexual precocity following treatment of Granulosa Cell Tumor of the Ovary. Cureus. 2022;14(2):e22676.

Calcaterra V, Nakib G, Pelizzo G, Rundo B, Anna Rispoli G, Boghen S, et al. Central precocious puberty and granulosa cell ovarian Tumor in an 8-year old female. Pediatr Rep. 2013;5(3):e13.

Almeida MQ, Brito VN, Lins TS, Guerra-Junior G, de Castro M, Antonini SR, et al. Long-term treatment of familial male-limited precocious puberty (testotoxicosis) with cyproterone acetate or ketoconazole. Clin Endocrinol. 2008;69(1):93–8.

Jeha GS, Lowenthal ED, Chan WY, Wu SM, Karaviti LP. Variable presentation of precocious puberty associated with the D564G mutation of the LHCGR gene in children with testotoxicosis. J Pediatr. 2006;149(2):271–4.

Schmidt H, Kiess W. Secondary central precocious puberty in a girl with McCune-Albright syndrome responds to treatment with GnRH analogue. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metabolism: JPEM. 1998;11(1):77–81.

Cattoni A, Albanese A. Case report: fluctuating Tumor markers in a boy with gonadotropin-releasing hormone-independent precocious puberty induced by a pineal germ cell Tumor. Front Pead. 2022;10:940656.

Commentz JC, Uhlig H, Henke A, Hellwege HH, Willig RP. Melatonin and 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate excretion is inversely correlated with gonadal development in children. Horm Res. 1997;47(3):97–101.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HC and LZ designed and guided the work. HC and CM collected the case and drafted the article. HC, CM and LZ analyzed the case. HC and CM followed-up the subject. LZ guided interpretation and revision of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Data analysis was performed retrospectively, with all procedures and analysis approved by the local ethics committee according to the Declaration of Helsinki (IRB of Beijing Tiantan Hospital, Capital Medical University, KY2021-193-01).

Consent for publication

As the patient was under the age of 16, written informed consent for publication of clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from his parents.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Mo, CY. & Zhong, Ly. Central precocious puberty secondary to peripheral precocious puberty due to a pineal germ cell tumor: a case and review of literature. BMC Endocr Disord 23, 237 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01494-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01494-0