Abstract

Background

Metabolic dysfunction associated with fatty liver disease (MAFLD) is often correlated with obesity and hyperuricemia. The present study aimed to determine the association between serum uric acid (SUA) and central fat distribution in patients with MAFLD.

Methods

A total of 485 patients were classified into the following groups: (1) controls without MAFLD and hyperuricemia (HUA), (2) MAFLD with normal SUA, and (3) MAFLD with HUA. DUALSCAN HDS-2000 was used to measure visceral fat (VAT) and subcutaneous fat (SAT). Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) was used to measure body fat distribution.

Results

MAFLD patients with HUA had remarkably higher BMI, fasting insulin, OGIRT AUC, ALT, AST, TG, VAT, SAT, Adipo-IR, trunk fat mass, android fat, and total body fat than MAFLD patients with normal SUA (all p < 0.05). The increase in VAT, SAT, CAP, Adipo-IR, upper limbs fat mass, trunk fat mass, and android fat, as well as the percentage of MAFLD, were significantly correlated with the increase in SUA. The percentage of MAFLD patients with HUA increased significantly with increasing VAT or SAT, as determined by the Cochran–Armitage trend test (all p < 0.05). Furthermore, VAT (OR = 1.01 CI: 1.00, 1.03; p < 0.05) and adipo-IR (OR = 1.09 CI: 1.00, 1.19; p < 0.05) were associated with circling SUA in MAFLD after adjusting for sex, age, TG, TC, HOMA-IR, and BMI.

Conclusion

Abdominal fat promotes the co-existence of HUA and MAFLD, while weight loss, especially, decreasing VAT, is of great importance to decrease SUA levels and manage MAFLD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

MAFLD redefines fatty liver disease by focusing on metabolic abnormalities (irrespective of the underlying cause of chronic liver disease) and their pivotal role in the clinical outcomes of individuals with hepatic steatosis [1, 2]. It often parallels the prevalence of obesity and affects approximately 70–90% of overweight or obese patients [3]. Patients with MAFLD often experience other metabolic disorder complications, including type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome, and hyperuricemia [4, 5], as well as, an increased risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD) and related mortality. Although not every patient with hyperuricemia suffers from gout, hyperuricemia is a major etiologic factor for gout [6]. Furthermore, hyperuricemia has been strongly correlated with several metabolic diseases, like T2DM [7,8,9], metabolic syndrome [10,11,12] hypertension [13, 14], and CVD [11, 15,16,17]. Serum uric acid (SUA) has been frequently found to be significantly higher in morbidly obese patients compared to controls [18]. Elevated SUA is consistent with increasing metabolic characteristics and positively correlated with abdominal fat [18, 19]. Visceral fat has been reported as the most influential factor in hyperuricemia [19]. Moreover, the decrease in SUA level is positively associated with reduced visceral fat area in gout patients [20]. Various epidemiological and clinical studies have reported an association between hyperuricemia and Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [21,22,23]. Hyperuricemia has been shown to independently be related to both hepatic and visceral fat tissue quantified by computer tomography [19, 24]. A recent meta-analysis suggested that hyperuricemia is associated with an exacerbated risk of NAFLD [25]. However, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have evaluated the correlation between body fat distribution and SUA in patients with MFLAD. Therefore, this study aimed to determine the association between body fat distribution and SUA in MAFLD patients.

Patients and methods

Participants

Four hundred and eighty-five individuals (Including 260 males and 225 females) were enrolled in this study from inpatient or outpatient at the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University from December 2018 to October 2022. The participants were divided into the following three groups (Fig. 1): (1) normouricemic [controls without MAFLD and hyperuricemia (HUA)], n = 81; (2) MAFLD with normal SUA, n = 267; and (3) MAFLD with HUA, n = 137. The present study was approved by the Ethics Committee of our hospital (Chongqing, China) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study.

Hyperuricemia was defined as SUA over 420 umol/L [26, 27]. MAFLD was diagnosed according to the criteria reported by An international experts group [28].

All of the participants enrolled were aged 18–65 years. The exclusion criteria for the present study were as follows: i) patients with gout or a history of treated HUA, or other secondary HUA, ii) patients with other liver diseases and infectious diseases, severe CVD, renal dysfunction, malignant tumors, thyroid dysfunction, genetic disorders, or mental diseases, or under any medication that affects the present study.

Clinical and laboratory measurements

After 10–12 h of overnight fasting, peripheral blood samples were collected between 7 and 9 am. Anthropometric parameters, such as weight and height, were measured according to standardized protocols as done in our previous study [29]. Systemic systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were obtained by a designated nurse using a mercury sphygmomanometer, and the average of three consecutive measurements was considered. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (Kg) divided by the square of height (m2). The calculation of waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) involved dividing the waist circumference (in centimeters) by the hip circumference (in centimeters) [30]. Moreover, the WHR was categorized into two groups: android, characterized by a WHR of ≥ 0.85, and gynoid, indicated by a WHR of < 0.85. Liver steatosis by controlled attenuation parameter [CAP (dB/m)] was measured by liver ultrasonic attenuation at 3.5 MHz [31]. The levels of triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TC), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), free fatty acids (FFAs), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), and uric acid (UA) were determined by standard enzymatic assays as in previous study [32]. Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) was measured by ion-exchange high-performance chromatography and plasma glucose was measured-using the glucose oxidase method. Plasma insulin was measured by chemiluminescence. The homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as fasting plasma glucose (FPG, mmol/L) × fasting insulin (FINS, mU/L)/22.5 [33]. Adipose tissue insulin resistance (Adipo-IR) was calculated as free fatty acid (FFA, mmol/L) × fasting insulin (FINS, mU/L) [34]. The NAFLD score (NFS) was calculated as—1.675 + 0.037 × age (years) + 0.094 × BMI (kg/m2) + 1.13 × impaired fasting glucose/diabetes (yes = 1, no = 0) + 0.99 × AST/ALT ratio-0.013 × platelet count (109/L)—0.66 × albumin (g/dL) [35]. Fibrosis-4 (FIB-4) was calculated as age (years) × AST (U/L)/[platelet count (109/L) × ALT1/2 (U/L)] [36].

Oral glucose insulin release test (OGIRT)

The 75 g glucose-OGIRT test was conducted after 10-12 h of fasting in all participants. At 8 a.m. on the test day, all participants were given 75 g of oral glucose, and blood samples were collected at designated time points (0, 30, 60, and 120 min) to measure insulin.

Abdominal fat measurement

Visceral and subcutaneous fat were evaluated by Dual bioelectrical impedance (DUALSCAN HDS-2000) with the patient in a supine position on an empty stomach, in a quiet state, by a dedicated operator. A dual BIA instrument was used to calculate the cross-sectional area of visceral and subcutaneous fat at the level of the umbilicus based on the measurement of electrical potentials in two different body spaces, as previously described [37].

Body fat distribution measurements

Body fat distribution in patients with MAFLD was assessed by dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA, APEX 4.5.0.2, Hologic, USA). The fat mass was measured in the whole body including the head, trunk, android, upper limbs, thighs, and gynoid regions. The percentage of android fat and percentage of gynoid fat ratio (A/G ratio) was calculated.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS statistical software (Version 26.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA). Shapiro–Wilk test was used to detect normally distributed data. Normally distributed data are represented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) while data showing skewed distribution are represented as the median (interquartile range). Variables with a normal distribution were analyzed by ANOVA was used to compare among groups and the Bonferroni method was used to test to differences between groups; skewed distribution variables were analyzed by the Kruskal–Wallis 1-way test and the Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare variables between the certain two groups. In the pooled data, SUA was divided into quartiles and the Cochran–Armitage trend test was used to estimate the significant trends across increasing quartiles. The chi-squared test was used to analyze categorical data between different groups. Pearson correlation was used to determine the correlation of data. Unilinear and logistic regression analyses were performed to explore the correlation between SUA and fat distribution in MAFLD. Besides, we divided the visceral fat and subcutaneous fat into quartiles and used the Cochran–Armitage trend test to assess the significant trends through increasing quartiles. The two-tailed P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. For all statistical tests, P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Basic characteristics of the patients in different groups

Table 1 shows the basic characteristics the anthropometric, metabolic characteristics, and body fat distribution of the patients in the three groups. Compared to the control group, participants in the MAFLD with normal SUA and MAFLD with HUA groups had higher Weight, BMI, WHR, SBP, DBP, fasting insulin, ALT, AST, TG, VAT, SAT, CAP, FFA, Adipo-IR, trunk fat mass, android fat, total body fat, and lower HDL-C (all P < 0.05). As expected, the MAFLD with the HUA group had remarkably higher Weight, BMI, fasting insulin, OGIRT AUC, ALT, AST, TG, VAT, SAT, Adipo-IR, trunk fat mass, android fat mass, and total body fat than the MAFLD with normal SUA group (all P < 0.05). There were no statistically significant differences in TC, LDL-C, NFS, FIB-4, or numbers of metabolic syndromes between the MAFLD with HUA or with normal SUA groups. Furthermore, there were no statistically significant differences in WHR, SBP, DBP, HDL-C, CAP, and FFA (P > 0.05) between the two groups.

Comparison of fat distribution, prevalence of MAFLD, and metabolic syndrome (MS) across the quartile of SUA

We established that compared with MAFLD patients with normal SUA, those with HUA have much higher abdominal fat and are more insulin resistant, especially with a higher adipo-IR. We then mainly focused on determining how the fat distribution and prevalence of MAFLD changed with different levels of uric acid (Table 2). As expected, the BMI, WHR, fasting insulin, OGIRT AUC, VAT, SAT, CAP, Adipo-IR, upper limbs fat mass, trunk fat mass, and android fat mass was significantly increased with increasing SUA and the prevalence of MAFLD was also increased with increasing quartiles of SUA. Furthermore, the percentage of MS also significantly increased with increasing quartiles of SUA. However, no significant difference in percent total body fat, gynoid fat mass, and thighs fat mass was observed across various SUA quartiles.

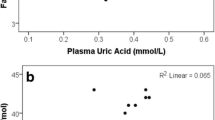

Correlations between fat distribution and SUA

The altered fat distribution and percentage of MAFLD across different circulating levels of SUA prompted us to explore the correlation between different fat deposits and SUA. As shown in Fig. 2, We found that SUA levels were significantly and positively associated with total fat mass (r = 0.292, p < 0.01), VAT (r = 0.305, p < 0.01), trunk fat mass (r = 0.294, p < 0.01), SAT (r = 0.354, p < 0.01) android fat (r = 0.276, p < 0.01), Adipo-IR (r = 0.325, p < 0.01), ratio of android and gynoid fat (r = 0.207), p < 0.05) and upper limbs fat mass (r = 0.299, p < 0.01). However, we didn’t find any significant correlation between SUA and percent of total body fat, thighs fat mass, gynoid fat mass, and the ratio of VAT and SAT. Next, we performed logistic regression analysis to explore variables that had independent associations with circulating SUA in MAFLD (Table 3). After adjusting for sex, age, blood pressure, and BMI, VAT (OR = 1.016 CI: 1.004, 1.027 p = 0.006) and adipo-IR (OR = 1.089 CI: 1.017, 1.166 p = 0.014) were still significant risk factors for SUA in MAFLD. After adjusting for sex, age, HbA1c, and BMI, VAT (OR = 1.018 CI: 1.004, 1.032, p = 0.009) and adipo-IR (OR = 1.079 CI: 1.006, 1.157, p = 0.033) were still significant risk factors for SUA in MAFLD. After adjusting for sex, age, HOMA-IR, and BMI, VAT (OR = 1.015 CI: 1.002, 1.027, p = 0.023) and adipo-IR (OR = 1.100 CI: 1.010, 1.198, p = 0.028) were still significant risk factors for SUA in MAFLD. Furthermore, after adjusting for sex, age, TG, TC, HOMA-IR, and BMI, VAT (OR = 1.014 CI: 1.001, 1.028, p = 0.032) and adipo-IR (OR = 1.094 CI: 1.002, 1.194, p = 0.046) were still independent risk factors for SUA in MAFLD.

Correlation between SUA level and fat in different regions. A Correlation between serum uric acid and total body fat. B Correlation between serum uric acid and visceral adipose tissue. C Correlation between serum uric acid and trunk fat mass. D Correlation between serum uric acid and subcutaneous adipose tissue. E Correlation between serum uric acid and android fat mass. F Correlation between serum uric acid and Adipo-IR. G Correlation between serum uric acid and android/gynoid ratio. H Correlation between serum uric acid and upper limbs fat mass. I Correlation between serum uric acid and total body fat (%). J Correlation between serum uric acid and Thighs fat mass. K Correlation between serum uric acid and gynoid fat mass. L Correlation between serum uric acid and VAT/SAT ratio

Prevalence of MAFLD with or without HUA across the quartiles of VAT and SAT

Furthermore, to explore whether the prevalence rates of MAFLD with or without HUA increased with increasing abdominal fat, we further divided VAT and SAT into quartiles. As predicted, the percentage of MAFLD with HUA increased significantly with increasing quartiles of VAT or SAT, while the percentage of normal people significantly declined with increasing abdominal fat, as determined by the Cochran–Armitage trend test (all p < 0.05). However, no such association was observed in the case of participants with MAFLD with normal SUA (Table 4).

Changes in SUA after decreasing SAT and VAT in MAFLD

We also assessed the changes in SUA in 44 weight-loss MAFLD patients. As shown in Table 5, after weight loss, SUA significantly reduced (before 396.41 ± 118.80 vs after 362.52 ± 104.72; p < 0.05). Furthermore, the changes in SUA levels were significantly correlated with changes in body fat (Table 6), especially VAT (r = 0.32, p < 0.05), SAT (r = 0.40, p < 0.01), truck fat (r = 0.97, P < 0.01), and android fat (r = 0.89, p < 0.01), but not thighs fat mass (p > 0.05), gynoid fat (p > 0.05), and upper limbs fat mass (p > 0.05) (Table 6).

Discussion

In the present study, we uncovered the correlation between SUA and fat distribution in MAFLD patients. Our findings may supplement previous research and have therapeutic implications in both HUA and MAFLD in clinical practice. We established that abdominal fat promotes the co-existence of HUA and MAFLD, VAT and adipo-IR are independent risk factors for HUA in MAFLD, and weight loss, especially, decreasing VAT, is important in lowering SUA and managing MAFLD. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate the association between body fat distribution and SUA in patients with MAFLD.

The present study showed there were no significant differences in NFS, FIB-4, and CAP between MAFLD patients with normal SUA or with HUA, which implies that fat deposition status and fibrosis indices were comparable between the two MAFLD groups. However, MAFLD patients with HUA had much higher fasting insulin, OGIRT AUC, VAT, SAT, Adipo-IR, trunk fat mass, and android fat mass than those with normal SUA, indicating that MAFLD patients with HUA are characterized by more central fat and insulin resistance. Furthermore, with increasing quartiles of SUA, fat accumulation in central deposits like the abdomen, trunk, and android increased; this is also a feature of insulin resistance, especially, adipose tissue insulin resistance. Previous studies showed that elevated serum uric facilitates insulin resistance-mediated accumulation of visceral fat [38, 39]. Whereas low SUA levels with anti-hyperuricemia promote overall metabolic conditions and loss of VAT [20, 40]. The role of increased SUA appears to be greater when considering Adipo-IR as a promoter of VAT accumulation [38]. Increased intracellular SUA levels upregulate lipogenesis-related proteins directly and dose-dependently and downregulate the expression of lipolysis-related proteins and thus, induce excessive TG accumulation in adipocytes [41]. UA promotes citrate conversion to acetyl-CoA for de novo lipogenesis in hepatocytes [42], leading to an increase in circulating FFA. Elevated FFA in adipocytes further converts to TG and finally deteriorates visceral obesity. These mechanisms explain why HUA correlated strongly with VAT in MALFD patients.

In the present study, we found that both HOMA-IR and Adipo-IR were significantly higher in patients with MAFLD than the controls; whereas only Adipo-IR was higher in MAFLD patients with HUA than those with normal SUA. Most importantly, Adipo-IR increased with increasing SUA. While HOMA-IR is a general index of IR, the Adipo-IR index has been widely used as a simple, unique, and reliable predictor of IR in adipose tissue in metabolic disorders associated with obesity [43,44,45,46,47]. Adipo-IR is reported to estimate insulin resistance in adipose tissue reasonably well compared with a gold standard clamp with FFA tracers [43]. Although the two indices are highly correlated with each other theoretically and practically [34, 48], a discordance between them for indicating metabolic diseases has been reported [49, 50]. Adipo-IR was reported to link with hypertriglyceridemia and visceral adiposity more closely [50], which is in accordance with our result. Furthermore, Adipo-IR is more related to the severity of liver fibrosis compared to HOMA-IR [51]. We also found that Adipo-IR is an independent risk factor for HUA in MAFLD patients adjusted for HOMA-IR, BMI, TG, and TC. Moreover, weight loss improved Adipo-IR and HUA in MAFLD patients. Therefore, the role of adipose tissues in MAFLD with HUA is more pathogenic, and more attention should be paid to Adipo-IR when considering HUA in MAFLD patients.

Notably, in this study, SUA levels in MAFLD patients were back to normal after weight loss, without the use of anti-HUA drugs. It is well established that weight gain has been strongly correlated with increasing SUA levels [52, 53] and weight loss can reduce the levels of SUA [54, 55]. Renal excretion of urate could be reduced in condition of Obesity [56, 57]. Therefore, increased SUA levels are reportedly an outcome and not a cause of obesity [58], and obesity is assumed to lead to high SUA levels and thus, cause decreased inflammatory responses, endothelial dysfunction, nitric oxide production, and enhanced oxidative stress [59]. Previous studies have shown that obese individuals have a significantly higher risk of gout than those with normal weight, regardless of sex and race [60,61,62,63]. Furthermore, a recent study estimating the correlation between weight change and obesity and the incidence of gout in a retrospective US adults study concluded that participants with a stable obese BMI gaining weight who were non-obese previously were consistently associated with increased risk of gout. This strengthened the importance of keeping non-obese weight during adulthood, especially those obese individuals who got weight loss, to reduce gout risk continuously in their later life [64]. Therefore, we postulate that the main consideration for controlling HUA in obese individuals must be weight loss and not anti-HUA drugs. It is significant for obese HUA patients to maintain weight within the normal range over using anti-HUA drugs alone. Therefore, a normal body fat percentage is important for both HUA and future gout.

The strengths of our study are as follows. First, we assessed fat distribution in the light of SUA in MAFLD patients for the first time and showed that VAT and Adipo-IR were the independent risk factors of SUA in MALFD. Second, we tested the hypothesis that weight loss is more important in decreasing SUA in MAFLD than anti-HUA drugs and that keeping body weight within the normal range may reduce the risk of recurrence of HUA and future gout associated with increased weight.

There are several limitations to our study. First, we use ultrasonography and fibro scan to diagnose MAFLD. Although [1H]-MRS is noninvasive and considered the most accurate method, ultrasonography is sufficient correlated with MRS. Furthermore, although ultrasonography may underestimate fat contact, it does show better specificity. Second, the sample size is relatively small and limited our ability to account for potential confounders during the analysis. However, the present study is sufficient to show novel associations between body fat distribution and SUA in MAFLD patients. Additionally, this case–control study cannot prove causality, however, we carried out a pilot study to show that the extent of changes in body fat was correlated with a decrease in SUA in MAFLD. This phenomenon should be validated in future clinical studies.

Conclusions

This study is valuable in that it is the first study to assess the relationship between changes in SUA levels and changes in visceral fat in MAFLD patients. Supplementary to previous studies, the present study also shows that weight loss is of great importance in lowing SUA, as opposed to anti-HUA drugs in MAFLD patients. More importantly, VAT and Adipo-IR instead of other fat compartments were established as independent risk factors of HUA in MAFLD patients. We suggest that more attention should be paid to the role of excessive VAT in the development and occurrence of HUA in MAFLD patients.

Availability of data and materials

Data will be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- WHR:

-

Waist hip ratio

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- Ogirt AUC:

-

Area under Ogirt curve

- HbA1c:

-

Glycosylated hemoglobin A1c

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- LDL-c:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-c:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- SUA:

-

Serum uric acid

- VAT:

-

Visceral adipose tissue

- SAT:

-

Subcutaneous adipose tissue

- NFS:

-

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease fibrosis score

- FIB-4:

-

Fibrosis-4 score

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance

- CAP:

-

Controlled attenuation parameters of liver

- FFA:

-

Free fatty acid

- Adipo-IR:

-

Adipose tissue insulin resistance

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

- MAFLD:

-

Metabolic dysfunction associated with fatty liver disease

References

Eslam M, Sanyal AJ, George J. MAFLD: A Consensus-Driven Proposed Nomenclature for Metabolic Associated Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(7):1999-2014.e1991.

Kang SH, Cho Y, Jeong SW, Kim SU, Lee JW. From nonalcoholic fatty liver disease to metabolic-associated fatty liver disease: Big wave or ripple? Clin Mol Hepatol. 2021;27(2):257–69.

Sahini N, Borlak J. Recent insights into the molecular pathophysiology of lipid droplet formation in hepatocytes. Prog Lipid Res. 2014;54:86–112.

Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, George J, Bugianesi E. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1):11–20.

Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease-Meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD). 2016;64(1):73–84.

Doherty M. New insights into the epidemiology of gout. Rheumatology (Oxford, England). 2009;48 Suppl 2:ii2-ii8.

Kodama S, Saito K, Yachi Y, Asumi M, Sugawara A, Totsuka K, Saito A, Sone H. Association between serum uric acid and development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1737–42.

Bhole V, Choi JW, Kim SW, de Vera M, Choi H. Serum uric acid levels and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective study. Am J Med. 2010;123(10):957–61.

Dehghan A, van Hoek M, Sijbrands EJ, Hofman A, Witteman JC. High serum uric acid as a novel risk factor for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(2):361–2.

Bombelli M, Quarti-Trevano F, Tadic M, Facchetti R, Cuspidi C, Mancia G, Grassi G. Uric acid and risk of new-onset metabolic syndrome, impaired fasting glucose and diabetes mellitus in a general Italian population: data from the Pressioni Arteriose Monitorate E Loro Associazioni study. J Hypertens. 2018;36(7):1492–8.

Ford ES, Li C, Cook S, Choi HK. Serum concentrations of uric acid and the metabolic syndrome among US children and adolescents. Circulation. 2007;115(19):2526–32.

Nakagawa T, Hu H, Zharikov S, Tuttle KR, Short RA, Glushakova O, Ouyang X, Feig DI, Block ER, Herrera-Acosta J, et al. A causal role for uric acid in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290(3):F625-631.

Kuwabara M, Hisatome I, Niwa K, Hara S, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Bjornstad P, Nakagawa T, Andres-Hernando A, Sato Y, Jensen T, et al. Uric Acid Is a Strong Risk Marker for Developing Hypertension From Prehypertension: A 5-Year Japanese Cohort Study. Hypertension. 2018;71(1):78–86.

Zhang W, Sun K, Yang Y, Zhang H, Hu FB, Hui R. Plasma uric acid and hypertension in a Chinese community: prospective study and metaanalysis. Clin Chem. 2009;55(11):2026–34.

Cannon PJ, Stason WB, Demartini FE, Sommers SC, Laragh JH. Hyperuricemia in primary and renal hypertension. N Engl J Med. 1966;275(9):457–64.

Lehto S, Niskanen L, Rönnemaa T, Laakso M. Serum uric acid is a strong predictor of stroke in patients with non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Stroke. 1998;29(3):635–9.

Tuttle KR, Short RA, Johnson RJ. Sex differences in uric acid and risk factors for coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 2001;87(12):1411–4.

İnanir M. Serum uric acid (SUA) in morbidly obese patients and its relationship with metabolic syndrome. Aging Male. 2020;23(5):1165–9.

Hikita M, Ohno I, Mori Y, Ichida K, Yokose T, Hosoya T. Relationship between hyperuricemia and body fat distribution. Intern Med. 2007;46(17):1353–8.

Ran Z, Xue X, Han L, Terkeltaub R, Merriman TR, Zhao T, He Y, Wang C, Li X, Liu Z, et al. Decrease in Serum Urate Level Is Associated With Loss of Visceral Fat in Male Gout Patients. Front Endocrinol. 2021;12: 724822.

Hu XY, Li Y, Li LQ, Zheng Y, Lv JH, Huang SC, Zhang W, Liu L, Zhao L, Liu Z, et al. Risk factors and biomarkers of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: an observational cross-sectional population survey. BMJ Open. 2018;8(4): e019974.

Sertoglu E, Ercin CN, Celebi G, Gurel H, Kayadibi H, Genc H, Kara M, Dogru T. The relationship of serum uric acid with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(6):383–8.

Sirota JC, McFann K, Targher G, Johnson RJ, Chonchol M, Jalal DI. Elevated serum uric acid levels are associated with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease independently of metabolic syndrome features in the United States: Liver ultrasound data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Metabolism. 2013;62(3):392–9.

Yamada A, Sato KK, Kinuhata S, Uehara S, Endo G, Hikita Y, Fujimoto WY, Boyko EJ, Hayashi T. Association of Visceral Fat and Liver Fat With Hyperuricemia. Arthritis Care Res. 2016;68(4):553–61.

Zhou Y, Wei F, Fan Y. High serum uric acid and risk of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Biochem. 2016;49(7–8):636–42.

Zhang Y, Cai M, Dilimulati D, Lin Z, Sun H, Cui R, Fei H, Gao X, Zeng Q, Shao X, et al. Correlation Between Serum Uric Acid and Body Fat Distribution in Patients With Polycystic Ovary Syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12: 782808.

Guo Y, Huang H, Chen Y, Shen C, Xu C. Association between circulating cystatin C and hyperuricemia: a cross-sectional study. Clin Rheumatol. 2022;41(7):2143–51.

Eslam M, Newsome PN, Sarin SK, Anstee QM, Targher G, Romero-Gomez M, Zelber-Sagi S, Wai-Sun Wong V, Dufour JF, Schattenberg JM, et al. A new definition for metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease: An international expert consensus statement. J Hepatol. 2020;73(1):202–9.

Wang C, Peng JJ, Miao H, Liu DF, Zhang LL. Decreased Plasma MANF Levels are Associated with Type 2 Diabetes. Biomed Environ Sci. 2021;34(3):236–40.

Zheng RD, Chen ZR, Chen JN, Lu YH, Chen J. Role of Body Mass Index, Waist-to-Height and Waist-to-Hip Ratio in Prediction of Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2012;2012: 362147.

Sasso M, Beaugrand M, de Ledinghen V, Douvin C, Marcellin P, Poupon R, Sandrin L, Miette V. Controlled attenuation parameter (CAP): a novel VCTE™ guided ultrasonic attenuation measurement for the evaluation of hepatic steatosis: preliminary study and validation in a cohort of patients with chronic liver disease from various causes. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36(11):1825–35.

Wang C, He M, Peng J, Li S, Long M, Chen W, Liu D, Yang G, Zhang L. Increased plasma osteopontin levels are associated with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cytokine. 2020;125: 154837.

Gayoso-Diz P, Otero-Gonzalez A, Rodriguez-Alvarez MX, Gude F, Cadarso-Suarez C, García F, De Francisco A. Insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) levels in a general adult population: curves percentile by gender and age. The EPIRCE study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(1):146–155.

Gastaldelli A, Harrison SA, Belfort-Aguilar R, Hardies LJ, Balas B, Schenker S, Cusi K. Importance of changes in adipose tissue insulin resistance to histological response during thiazolidinedione treatment of patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD). 2009;50(4):1087–93.

Angulo P, Hui JM, Marchesini G, Bugianesi E, George J, Farrell GC, Enders F, Saksena S, Burt AD, Bida JP, et al. The NAFLD fibrosis score: a noninvasive system that identifies liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD). 2007;45(4):846–54.

Shah AG, Lydecker A, Murray K, Tetri BN, Contos MJ, Sanyal AJ. Comparison of noninvasive markers of fibrosis in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7(10):1104–12.

Ida M, Hirata M, Odori S, Mori E, Kondo E, Fujikura J, Kusakabe T, Ebihara K, Hosoda K, Nakao K. Early changes of abdominal adiposity detected with weekly dual bioelectrical impedance analysis during calorie restriction. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2013;21(9):E350-353.

Fernández-Chirino L, Antonio-Villa NE, Fermín-Martínez CA, Márquez-Salinas A, Guerra EC, Vargas-Vázquez A, Almeda-Valdés P, Gómez-Velasco D, Viveros-Ruiz TL, Rojas R, et al. Elevated serum uric acid is a facilitating mechanism for insulin resistance mediated accumulation of visceral adipose tissue. Clin Endocrinol. 2022;96(5):707–18.

Baldwin W, McRae S, Marek G, Wymer D, Pannu V, Baylis C, Johnson RJ, Sautin YY. Hyperuricemia as a mediator of the proinflammatory endocrine imbalance in the adipose tissue in a murine model of the metabolic syndrome. Diabetes. 2011;60(4):1258–69.

Chen J, Ge J, Zha M, Miao JJ, Sun ZL, Yu JY. Effects of Uric Acid-Lowering Treatment on Glycemia: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:577.

Su M, Sun L, Li W, Liu H, Liu Y, Wei Y, Yuan Y, Zheng L, Yin S, Dai C, et al. Metformin alleviates hyperuricaemia-induced serum FFA elevation and insulin resistance by inhibiting adipocyte hypertrophy and reversing suppressed white adipose tissue beiging. Clin Sci (Lond). 2020;134(12):1537–1553.

Lanaspa MA, Sanchez-Lozada LG, Choi YJ, Cicerchi C, Kanbay M, Roncal-Jimenez CA, Ishimoto T, Li N, Marek G, Duranay M, et al. Uric acid induces hepatic steatosis by generation of mitochondrial oxidative stress: potential role in fructose-dependent and -independent fatty liver. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(48):40732–44.

Søndergaard E, Espinosa De Ycaza AE, Morgan-Bathke M, Jensen MD. How to Measure Adipose Tissue Insulin Sensitivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(4):1193–1199.

Fabbrini E, Magkos F, Conte C, Mittendorfer B, Patterson BW, Okunade AL, Klein S. Validation of a novel index to assess insulin resistance of adipose tissue lipolytic activity in obese subjects. J Lipid Res. 2012;53(2):321–4.

Cai X, Xia L, Pan Y, He D, Zhu H, Wei T, He Y. Differential role of insulin resistance and β-cell function in the development of prediabetes and diabetes in middle-aged and elderly Chinese population. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2019;11:24.

Ter Horst KW, van Galen KA, Gilijamse PW, Hartstra AV, de Groot PF, van der Valk FM, Ackermans MT, Nieuwdorp M, Romijn JA, Serlie MJ. Methods for quantifying adipose tissue insulin resistance in overweight/obese humans. Int J Obes (2005). 2017;41(8):1288–1294.

Li X, Liu J, Zhou B, Li Y, Wu Z, Meng H, Wang G. Sex Differences in the Effect of Testosterone on Adipose Tissue Insulin Resistance From Overweight to Obese Adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2021;106(8):2252–63.

Rydén M, Andersson DP, Arner P. Usefulness of surrogate markers to determine insulin action in fat cells. Int J Obes 2005. 2020;44(12):2436–2443.

Sun H, Chang X, Bian N, An Y, Liu J, Leng S, Wang G. Adipose Tissue Insulin Resistance Is Positively Associated With Serum Uric Acid Levels and Hyperuricemia in Northern Chinese Adults. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13: 835154.

Song Y, Søndergaard E, Jensen MD. Unique Metabolic Features of Adults Discordant for Indices of Insulin Resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2020;105(8):e2753-2763.

Rosso C, Kazankov K, Younes R, Esmaili S, Marietti M, Sacco M, Carli F, Gaggini M, Salomone F, Møller HJ, et al. Crosstalk between adipose tissue insulin resistance and liver macrophages in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Hepatol. 2019;71(5):1012–21.

Glynn RJ, Campion EW, Silbert JE. Trends in serum uric acid levels 1961–1980. Arthritis Rheum. 1983;26(1):87–93.

Villegas R, Xiang YB, Cai Q, Fazio S, Linton M, Li H, Elasy T, Zheng W, Shu XO. Prevalence and determinants of hyperuricemia in middle-aged, urban Chinese men. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8(3):263–70.

Yamashita S, Matsuzawa Y, Tokunaga K, Fujioka S, Tarui S. Studies on the impaired metabolism of uric acid in obese subjects: marked reduction of renal urate excretion and its improvement by a low-calorie diet. Int J Obes. 1986;10(4):255–64.

Zhu Y, Zhang Y, Choi HK. The serum urate-lowering impact of weight loss among men with a high cardiovascular risk profile: the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(12):2391–9.

Matsuura F, Yamashita S, Nakamura T, Nishida M, Nozaki S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y. Effect of visceral fat accumulation on uric acid metabolism in male obese subjects: visceral fat obesity is linked more closely to overproduction of uric acid than subcutaneous fat obesity. Metabolism. 1998;47(8):929–33.

Gao B, Zhou J, Ge J, Zhang Y, Chen F, Lau WB, Wan Y, Zhang N, Xing Y, Wang L, et al. Association of maximum weight with hyperuricemia risk: a retrospective study of 21,414 Chinese people. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11): e51186.

Lyngdoh T, Vuistiner P, Marques-Vidal P, Rousson V, Waeber G, Vollenweider P, Bochud M. Serum uric acid and adiposity: deciphering causality using a bidirectional Mendelian randomization approach. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(6): e39321.

Chaudhary K, Malhotra K, Sowers J, Aroor A. Uric Acid - key ingredient in the recipe for cardiorenal metabolic syndrome. Cardiorenal Med. 2013;3(3):208–20.

Jia G, Shu XO, Liu Y, Li HL, Cai H, Gao J, Gao YT, Wen W, Xiang YB, Zheng W. Association of Adult Weight Gain With Major Health Outcomes Among Middle-aged Chinese Persons With Low Body Weight in Early Adulthood. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12): e1917371.

Evans PL, Prior JA, Belcher J, Mallen CD, Hay CA, Roddy E. Obesity, hypertension and diuretic use as risk factors for incident gout: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):136.

Puig JG, Martínez MA. Hyperuricemia, gout and the metabolic syndrome. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2008;20(2):187–91.

McAdams-DeMarco MA, Maynard JW, Baer AN, Coresh J. Hypertension and the risk of incident gout in a population-based study: the atherosclerosis risk in communities cohort. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2012;14(10):675–9.

Bai L, Zhou JB, Zhou T, Newson RB, Cardoso MA. Incident gout and weight change patterns: a retrospective cohort study of US adults. Arthritis Res Ther. 2021;23(1):69.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the patients and healthy participants enrolled in the study.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 81300702 to L.L.Z.), the Natural Science Foundation Project of Chongqing CSTC (cstc2018jcyjAXO210 to L.L.Z. and CSTB2022NSCQMSX1008 to C.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T. and J.L. contributed to the analysis of the data and the drafting of the manuscript. X.Y.C, Q.W. contributed to the analysis of the data. M.H. and W.W.C. revised and approved the final version of the manuscript. C.W. and L.L.Z. contributed to the study design, the drafting of the manuscript and critical discussion and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (Chongqing, China), approval number 20238. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants in the study. All methods in the current research were performed in accordance with the declaration of Helsinki’s guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tao, M., Liu, J., Chen, X. et al. Correlation between serum uric acid and body fat distribution in patients with MAFLD. BMC Endocr Disord 23, 204 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01447-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-023-01447-7