Abstract

Background

Limited data show that changes in fasting plasma glucose (FPG changes) are related to the incidence of type 2 diabetes (T2D). We aimed to correlate FPG changes with incident diabetes and evaluate FPG changes as a marker to screen participants at high risk of T2D in China.

Methods

A total of 116,816 individuals were followed during a median follow-up of 3.10 years by secondary analysis in a nondiabetic Chinese cohort. The turning points were derived from a receiver operating characteristic curve. Hazard ratios (HRs) were evaluated by Cox proportional hazards models.

Results

A total of 2669 cases of T2D were identified (788 women and 1881 men). The age-standardized incidence of diabetes was 12.87 per 1000 person-years (women: 11.04; men: 14.69). A nonlinear relationship between FPG changes and incident diabetes is shown by the fitting curves. The curves were categorized into three stages by two turning points (-0.04 and 1.25 mmol/L) and conformed to the hook-like pattern: an initial decrease (stage-1), then a transient sharp elevation (stage-2), followed by a slow increase (stage-3). HRs per SD of FPG changes on incident diabetes varied with stage: stage-1: 0.16 (0.12, 0.23), stage-2: 0.20 (0.15, 0.28) and stage-3: 0.22 (0.16, 0.31). Compared with stage-1, the HR in stage-3 was significantly higher at 28.05 (23.99, 32.79), while the increase in stage-2 was slight at 2.16 (1.79, 2.61), and the HR in stage-3 rose to 30.09 (25.02, 36.19).

Conclusions

FPG changes had a strong correlation with the incidence of T2D and was a steady indicator that was used to distinguish the participants at high risk of diabetes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In recent decades, type 2 diabetes (T2D) has become a large and ever-growing threat and one of the most important public health issues in virtually every region of the world [1]. According to the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS), the prevalence of diagnosed diabetes doubled from 1990 to 2016 (3.5% to 9.7%) [2, 3]. In China, the prevalence of diabetes also increased rapidly from less than 1% in 1980 to 11.2% in 2018 [4]. The threat was consistently underestimated because a significant proportion remained undiagnosed [5,6,7]. The prediction from the International Diabetes Federation is that 600 million people worldwide will be living with diabetes in 2035 [6, 8]. A high incidence of diabetes-specific complications, such as kidney failure and peripheral artery disease, has a severe impact on quality of life in diabetic patients [9]. Increasingly, diabetes and its complications also bring a heavy burden to patients and the health system [10].

The prevention of diabetes is more important than its treatment. Tracking the evolving epidemiology, it has become clear that the risk factors for T2D include ethnicity, obesity, Western lifestyle, socioeconomic status, prediabetes, and pregnancy [1, 6, 8, 11,12,13]. Therefore, some traditional risk factors are widely used clinically to predict the occurrence of diabetes, including fasting plasma glucose (FPG), body mass index (BMI), diet, physical activity and metabolic syndrome [14,15,16,17,18,19]. Among these factors, FPG may be the core predictor of the onset of diabetes [20,21,22]. In a recent study with 10,796 individuals (aged > 20 years), approximately 70% of prediabetes patients (according to the IFG-ADA: FPG 5.6–6.9 mmol/L) developed T2D within 10 years [23].

Recently, some new metabolic markers, especially variables combined with traditional risk factors, have been found to be closely related to the incidence of T2D.

The triglyceride (TG) to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) ratio (TG/HDL ratio) is a good marker to identify insulin resistance in children and adults and is a useful surrogate indicator of future incident type 2 diabetes [24,25,26]. Another new metabolic marker, the fasting triglyceride-glucose (TyG) index, precedes and significantly predicts T2D [27]. During a median follow-up of 6.17 years in the Tehran Lipid and Glucose Study (TLGS) of urban Iranians, FPG changes was an independent predictor (HR 1.57 [1.31, 1.88]) and the highest quartile of FPG changes increased the T2D risk to 1.65 [1.20, 2.27] compared with the lowest quartile [21]. However, there are limited data on the association between FPG changes and the incidence of diabetes, due to the size of the population and the fact that almost no literature from our region is available on the subject. In our study, we compared these metabolic markers and attempted to develop a simple clinical approach to identify the individuals at greatest risk of incident diabetes by secondary analysis in a nondiabetic Chinese multicenter cohort.

Material & methods

Study design and patients

The clinical data were obtained from a public database (https://datadryad.org) and were recorded from January 2010 to December 2016, which was offered by Chen et al. [28]. According to the previous literature, a total of 211,833 subjects were contacted [28, 29]. Briefly, all participants older than 20 years of age were candidates, with complete or valid information, including sociodemographic variables (age and sex), clinical data (height, body weight, body mass index, blood pressure and family history of diabetes), lifestyle data (smoking and alcohol consumption) and biochemical tests (fasting plasma glucose, LDL, HDL, total cholesterol, and triglyceride). In this retrospective cohort study, the following participants were excluded at baseline: those with extreme body mass index (BMI) (< 15 kg/m2 or > 55 kg/m2), those with shorter visit intervals (< 2 years) and those with diabetes or hypoglycemia at baseline (fasting plasma glucose ≥ 7.0 mmol/L or ≤ 2.8 mmol/L). The diagnosis of incident diabetes was defined as fasting plasma glucose of ≥ 7.00 mmol/L and/or self-reported diabetes during the follow-up period. Moreover, the statistical method boxplot was used to remove 15 outliers of FPG changes. A total of 116,816 participants (53,970 females, 62,846 males) took part in the study. The selection process of the participants was specifically explained previously [28, 29].

Definitions

The metabolic markers considered were FPG, triglyceride, total cholesterol, and HDL cholesterol, as well as the FPG changes, TyG index and TG/HDL ratio. In our study, FPG changes was defined as the difference between the baseline and final visit FPG (FPG2) (mmol/L) [30]. Participants were excluded with extreme FPG changes (> 15 mmol/L) (N = 5). The triglyceride–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration ratio (TG/HDL ratio) was determined by the serum TG (mmol/L): HDL concentration (mmol/L) ratio [13]. The triglyceride × fasting plasma glucose (TyG) index was calculated as the natural logarithm (Ln) of [TG (mg/dL) ⁎ glucose (mg/dL)/2] [31].

According to the definition of by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the World Health Organization (WHO), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was analyzed as a categorical variable (< 5.6, 5.6 – 6.0 and 6.1 – 6.9 mmol/L) [7, 32, 33].

Taking into account the effect of the reproductive system on incident diabetes (especially in women), age was analyzed as a ca impaired fasting glucose (IFG)tegorical variable (20–45, 46–55, 56–65 and ≥ 66 years) [34, 35]. As recommended by the Working Group on Obesity in China, normal weight was defined as a BMI of 18.5–23.9 kg/m2, overweight as a BMI of 24.0–27.9 kg/m2 and obesity as a BMI of 28.0 kg/m2 or higher [36]. According to the 2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension, a normal level was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) < 120 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) < 80 mmHg; prehypertension was defined as SBP 120–139 mmHg and DBP 80–89 mmHg; and hypertension was defined as systolic BP (SBP) ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) ≥ 90 mmHg [37]. Hyperlipidemia was diagnosed according to the Chinese Guidelines for the Management of Dyslipidemia in Adults [38]. Triglyceride (TG) was analyzed as a categorical variable (< 1.7, 1.7—2.2 and ≥ 2.3 mmol/L); total cholesterol (TC) was < 5.2, 5.2 – 6.1 and ≥ 6.2 mmol/L; LDL was < 3.4, 3.4 – 4.0 and ≥ 4.1 mmol/L; and HDL was < 1 and ≥ 1 mmol/L. According to the definition of impaired fasting glucose (IFG) by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the World Health Organization (WHO), fasting plasma glucose (FPG) was analyzed as a categorical variable (< 5.6, 5.6 – 6.0 and 6.1 – 6.9 mmol/L) [7, 32, 33].

Statistical analysis

Data analyses were performed using STATA (Version 13.1, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). The study data were analyzed for normal distribution, and data with normal and nonnormal distributions were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (interquartile range), respectively. Time-to-event Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the hazard ratio (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of incident diabetes. The Pearson correlation coefficient is typically used for jointly normally distributed data (data that follow a bivariate normal distribution). For nonnormally distributed continuous data, for ordinal data, or for data with relevant outliers, a Spearman rank correlation can be used as a measure of a monotonic association.

The metabolic markers considered were FPG, triglyceride, total cholesterol and HDL, as well as the FPG changes, TyG index and TG/HDL ratio. Constructing receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves was used to identify the clinical utility of metabolic markers in the prediction of the onset of diabetes, which depicts the relationship between sensitivity/specificity test results for each metabolic marker [16]. Areas under the ROC curves were compared using the method of Hanley and McNeil [16]. The metabolic marker for predicting the onset of diabetes with the statistically significantly better ROC was selected for turning point analysis to identify specific values by the fitting curves of diabetes probability [16]. We also divided the curves into three different stages by two turning points, and each stage was also divided into three tertiles. For the prospective analyses, we plotted cumulative Kaplan–Meier curves for diabetes development during follow-up. All statistical analyses were performed with the statistical package R (http://www.R-project.org) and EmpowerStats (www.empowerstats.com, X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA).

Results

During a median follow-up of 3.10 years (maximum 7.56 years; minimum 2.00 years), 2669 cases of T2D were identified (788 women and 1881 men) among a total of 116,816 participants (53,970 females, 62,846 males). The age-standardized incidence of diabetes was 12.87 per 1000 person-years (women: 11.04; men: 14.69). Men had higher levels of basic clinical data (height, body weight, body mass index, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure), lifestyle data (smoking and alcohol consumption) and biochemical tests (FPG, LDL, total cholesterol and triglyceride) (Table S1). The FPG changes in women was 0.19 ± 0.60 mmol/L lower than that in men (0.25 ± 0.72 mmol/L).

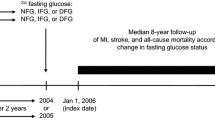

Almost all the fitting curves of diabetes probability of FPG changes were nonlinear and showed a sectional activity that conformed to the hook-like pattern: an initial decrease, then transient sharp elevation, followed by a slow increase. Hence, FPG changes were categorized into three stages based on the curves by two turning points (overall: -0.04 and 1.25; women: -0.05 and 1.16; men: -0.24 and 1.32, mmol/L) (Fig. 1). Importantly, the hook-like pattern was maintained, which was reconstructed via different levels of age, sex, HDL, TG, TC, SBP, DBP and history of diabetes (Fig. S1). Only the curves in participants with LDL ≥ 4.1 mmol/L and/or BMI < 18.5 kg/m2 had two stages (Fig. S1). We also found differences in the baseline characteristics of the participants (Table 1). There were similar baseline characteristics in participants with stage-1 and stage-2 FPG changes. However, participants with stage-3 had significantly different basic clinical data (body weight, body mass index, and systolic and diastolic blood pressure) and biochemical tests (LDL, total cholesterol, triglyceride, ALT and AST) in both women and men. Interestingly, from stage-1 to stage-3, the baseline FPG concentration continued to drop and all participants with diabetes in stage-1 were all diagnosed by self-reported (in Table S2). We also found participants with FPG baseline more than 5.6 mmol/L had a higher proportion of diabetics than those with a baseline FPG of less than 5.6 mmol/L both in women and men (in Table S2).

Importantly, the incidence of T2D varied with sex and the stages of FPG changes (stage-1: women 1.46, men 2.09, overall, 1.86; stage-2: women 2.14, men 5.59, overall, 3.86; stage-3: women 48.20, men 92.07, overall, 72.45, per 1000 person-years). HR per SD of FPG changes on incident diabetes was also affected by sex and stages of FPG changes. From stage-1 to stage-3, the HRs per SD of FPG changes in women were 0.10 (0.06, 0.18), 4.28 (3.07, 5.98) and 1.56 (1.50, 1.63), respectively; the HRs per SD in men were 0.20 (0.13, 0.30), 8.32 (6.73, 10.29) and 1.27 (1.24, 1.30), respectively; and the overall HRs per SD were 0.16 (0.12, 0.23), 0.20 (0.15, 0.28) and 0.22 (0.16, 0.31), respectively. Compared with stage-1, in women, the HR in stage-3 was significantly higher [22.08 (16.47, 29.59)], while the increase in stage-2 was not significant [1.12 (0.82, 1.51), P > 0.05]; in men, the HR in stage-2 slightly increased to 1.81 (1.54, 2.12), and that in stage-3 rose to 30.09 (25.02, 36.19).

Kaplan–Meier survival curves for cumulative diabetes-free probability based on sex and the stages of FPG changes are presented in Fig. 2. The cumulative diabetes-free probability was approximately 90% in stage-1 and stage-2 and in both stages at the end of the follow-up period. However, in stage-3, the cumulative diabetes-free probability decreased sharply with the increase in FPG changes, especially in the upper tertile of stage-3, which was close to zero at the end of follow-up (Fig. S2).

The cumulative diabetes free probability by Kaplan–Meier survival curves in women (A), men (B) and overall (C). FPG changes was defined as the difference between the baseline and final visit FPG (FPG2) (mmol/L). FPG changes was categorized into three stages based on the curves: stage-1: women < -0.24, men < -0.05 and overall < -0.04 mmol/L; stage-2: women -0.24—1.15, men -0.05—1.31 and overall -0.04—1.24 mmol/L; stage-3: women ≥ 1.16, men ≥ 1.32 and overall ≥ 1.25 mmol/L

We also compared the differences in the correlation between FPG changes and other metabolic markers with the incidence of diabetes by ROC curve analyses (Fig. S3). The area under the curve (AUC) by bootstrap varied with sex: FPG changes 0.864 [0.854, 0.873] (women 0.846; men 0.869), TyG index 0.766 [0.757, 0.774] (women 0.800; men 0.723) and TG/HDL ratio 0.699 [0.690, 0.709] (women 0.740; men 0.646). The predictive model based on FPG changes had better sensitivity (76.83%) and specificity (84.19%) than the model based on the TG/HDL ratio (67.78% and 62.35%, respectively) and TyG index (77.77% and 63.10%, respectively). FPG changes had a higher association with the onset of T2D in both men and women.

Discussion

The utility of FPG changes in predicting incident diabetes among nondiabetic participants has been reported in a prior study [21]. However, one main finding of this article was that the association between FPG changes and incident diabetes was significant by the secondary analysis in a nondiabetic Chinese multicenter cohort. The association of FPG changes might be stronger than that of other metabolic variables, including TG, FPG, BMI, TG/HDL ratio and TyG index (Fig. S3). The area under the curve (AUC) by bootstrapping for FPG change was highest among these metabolic variables. The sensitivity and specificity of the predictive model based on FPG changes were also higher than those of the TyG index and TG/HDL ratio. The TyG index and TG/HDL ratio were recently suggested as useful diagnostic markers to predict insulin resistance and as predictors for incident diabetes and arterial stiffness [18, 39]. The TyG index and TG/HDL ratio are two reliable alternative markers for insulin resistance in South American overweight and obese children and adolescents [39]. In a 12-year longitudinal study of the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study cohort, a higher TyG index preceded and significantly predicted T2D among community-dwelling middle-aged and elderly lean Koreans [27]. The advantage of FPG changes are that it might represent the difference between the final and baseline FPG concentrations, and one of the two diagnostic criteria for diabetes in this study is mainly based on FPG at the final visit. In addition, the association between FPG changes and incident diabetes was sex-specific. This specificity may be derived from the differences of the baseline characteristics of the participants and incidence of diabetes between men and women (Table S1 and Fig. 1).

Another glittering prize in this article was that the association of FPG changes with incident diabetes was nonlinear and conformed to a hook-like pattern. The hook-like pattern was a stable stage characteristic, consistent with the distribution of different levels of several variables (including age, sex, TG, SBP, and DBP). In our study, HRs per SD of FPG change on incident diabetes varied according to sex and stage: stage-1: 0.10 (0.06, 0.18) in women and 0.20 (0.13, 0.30) in men; stage-2: 4.28 (3.07, 5.98) in women and 8.32 (6.73, 10.29) in men; stage-3: 1.56 (1.50, 1.63) in women and 1.27 (1.24, 1.30) in men (Table 2). We also found that participants with FPG baseline more than 5.6 mmol/L had a higher proportion of diabetics than those with a baseline FPG of less than 5.6 mmol/L in different stages of FPG changes and different genders (in Table S2). These results are consistent with a large number of epidemiological studies confirming that baseline FPG can be highly predictive of T2D [37, 38]. In a 12-year longitudinal study (ELSA-Brasil), incident diabetes occurred in 5.6%, 22.7% and 53.9% of individuals with FPG < 5.6, 5.6–6.0 and 6.1–6.9 mmol/L, respectively [40]. In the Rotterdam Study with a follow-up of up to 14.7 years, the lifetime risk of progression from prediabetes to T2D was 74.0% in individuals aged 45 years [41].

The strength of our analysis is that the stages of FPG changes, especially stage-3 (FPG changes ≥ 1.16 mmol/L in women and ≥ 1.32 mmol/L in men), could distinguish the participants at higher risk of diabetes. Most of the baseline characteristics, incident diabetes and the HR of FPG changes were significantly higher in stage-3 than in stage-1 and stage-2, while the cumulative diabetes-free probability was markedly lower (Tables 1–2 and Fig. 2).

Our study has several limitations. Firstly, we evaluated the diagnosis of diabetes only by fasting plasma glucose levels in first and final visit. Neither oral glucose tolerance test data nor postprandial plasma glucose levels or glycated hemoglobin measurements of the participants were available to us, which led to underestimation of the incidence of diabetes in final visit. Secondly, the lower the basal fasting blood glucose, the lower the FPG change may be; hence, the prevalence of diabetes might also be lower. Thirdly, there were many missing data on smoking and drinking, so the impact of FPG changes was not adjusted for smoking and drinking. In addition, the participants with FPG changes beyond turning point 2 were very small, less than 10%, which limits the wide application of the research results. Finally, in our study, all participants in stage-1 and most of the participants in stage-2 were diagnosed by self-reported (in Table S2). The diagnosed differences in the proportion of participants with diabetes also influenced the FPG changes. Once diabetes occurs, measures are often taken to control glucose, which leads to a decrease in FPG in final visit.

Conclusion

We first reported that the correlation between FPG changes and the incidence of T2D was nonlinear by analyzing a nondiabetic Chinese cohort. FPG changes were a steady indicator that could distinguish the participants at higher risk of diabetes (with stage-3 FPG changes).

Availability of data and materials

The clinical data and materials were obtained from a public database (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.ft8750v).

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate transaminase

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CCR:

-

Endogenous creatinine clearance rate

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- FPG:

-

Fasting plasma glucose

- FPG changes:

-

Changes in fasting plasma glucose

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HR:

-

Hazard ratios

- IFG:

-

Impaired fasting glucose

- MBP:

-

Mean systolic blood pressure

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure; T2D: type 2 diabetes

- TG/HDL ratio:

-

Triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TyG:

-

Triglyceride-glucose

References

Thomas MC, Cooper ME, Zimmet P. Changing epidemiology of type 2 diabetes mellitus and associated chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(2):73–81.

Geiss LS, Wang J, Cheng YJ, Thompson TJ, Barker L, Li Y, Albright AL, Gregg EW. Prevalence and incidence trends for diagnosed diabetes among adults aged 20 to 79 years, United States, 1980–2012. JAMA. 2014;312(12):1218–26.

Mendola ND, Chen TC, Gu Q, Eberhardt MS, Saydah S. Prevalence of total, diagnosed, and undiagnosed diabetes among adults: United States, 2013–2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2018;319:1–8.

Li Y, Teng D, Shi X, Qin G, Qin Y, Quan H, Shi B, Sun H, Ba J, Chen B, et al. Prevalence of diabetes recorded in mainland China using 2018 diagnostic criteria from the American diabetes association: national cross sectional study. BMJ. 2020;369: m997.

Xu Y, Wang L, He J, Bi Y, Li M, Wang T, Wang L, Jiang Y, Dai M, Lu J, et al. Prevalence and control of diabetes in Chinese adults. JAMA. 2013;310(9):948–59.

Zimmet PZ, Magliano DJ, Herman WH, Shaw JE. Diabetes: a 21st century challenge. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2(1):56–64.

Jaacks LM, Siegel KR, Gujral UP, Narayan KM. Type 2 diabetes: a 21st century epidemic. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;30(3):331–43.

Guariguata L, Whiting DR, Hambleton I, Beagley J, Linnenkamp U, Shaw JE. Global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2013 and projections for 2035. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):137–49.

Harding JL, Pavkov ME, Magliano DJ, Shaw JE, Gregg EW. Global trends in diabetes complications: a review of current evidence. Diabetologia. 2019;62(1):3–16.

Mao W, Yip CW, Chen W. Complications of diabetes in China: health system and economic implications. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):269.

Kolb H, Martin S. Environmental/lifestyle factors in the pathogenesis and prevention of type 2 diabetes. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):131.

Jia W, Weng J, Zhu D, Ji L, Lu J, Zhou Z, Zou D, Guo L, Ji Q, Chen L, et al. Standards of medical care for type 2 diabetes in China 2019. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2019;35(6): e3158.

Armaghanian N, Atkinson F, Taylor N, Kench A, Brand-Miller J, Markovic T, Steinbeck K. Dietary intake in cystic fibrosis and its role in glucose metabolism. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(8):2495–500.

Ma H, Wu X, Guo X, Yang J, Ma X, Lv M, Li Y. Optimal body mass index cut-off points for prediction of incident diabetes in a Chinese population. J Diabetes. 2018;10(12):926–33.

Hemmingsen B, GimenezPerez G, Mauricio D, Roque IFM, Metzendorf MI, Richter B. Diet, physical activity or both for prevention or delay of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its associated complications in people at increased risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;12:CD003054.

McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Cheal K, Chu J, Lamendola C, Reaven G. Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(10):802–9.

Abbasi F, Reaven GM. Comparison of two methods using plasma triglyceride concentration as a surrogate estimate of insulin action in nondiabetic subjects: triglycerides x glucose versus triglyceride/high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Metabolism. 2011;60(12):1673–6.

Khan SH, Sobia F, Niazi NK, Manzoor SM, Fazal N, Ahmad F. Metabolic clustering of risk factors: evaluation of Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index) for evaluation of insulin resistance. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2018;10:74.

Valizadeh M, Alavi N, Mazloomzadeh S, Piri Z, Amirmoghadami H. The risk factors and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome in women with previous gestational diabetes. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;13(2): e21696.

Tabak AG, Jokela M, Akbaraly TN, Brunner EJ, Kivimaki M, Witte DR. Trajectories of glycaemia, insulin sensitivity, and insulin secretion before diagnosis of type 2 diabetes: an analysis from the Whitehall II study. Lancet. 2009;373(9682):2215–21.

Mozaffary A, Asgari S, Tohidi M, Kazempour-Ardebili S, Azizi F, Hadaegh F. Change in fasting plasma glucose and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: results from a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(5):e010889.

Yang CY, Li HY, Sung FC, Tan EC, Wei JN, Chuang LM. Relationship between fasting plasma glucose and incidence of diabetes in children and adolescents. Diabet Med. 2019;36(5):633–43.

DeJesus RS, Breitkopf CR, Rutten LJ, Jacobson DJ, Wilson PM, Sauver JS. Incidence Rate of Prediabetes Progression to Diabetes: Modeling an Optimum Target Group for Intervention. Popul Health Manag. 2017;20(3):216–23.

Lim TK, Lee HS, Lee YJ. Triglyceride to HDL-cholesterol ratio and the incidence risk of type 2 diabetes in community dwelling adults: A longitudinal 12-year analysis of the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2020;163: 108150.

Zhang J, Xu L, Li J, Sun L, Qin W, Ding G, Wang Q, Zhu J, Yu Z, Xie S, et al. Gender differences in the association between body mass index and health-related quality of life among adults:a cross-sectional study in Shandong, China. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1021.

Nur Zati Iwani AK. Jalaludin MY, Wan Mohd Zin RM, Fuziah MZ, Hong JYH, Abqariyah Y, Mokhtar AH, Wan Mohamud WN: TG : HDL-C Ratio Is a Good Marker to Identify Children Affected by Obesity with Increased Cardiometabolic Risk and Insulin Resistance. Int J Endocrinol. 2019;2019:8586167.

Park B, Lee HS, Lee YJ. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index as a predictor of incident type 2 diabetes among nonobese adults: a 12-year longitudinal study of the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study cohort. Transl Res. 2021;228:42–51.

Chen Y, Zhang XP, Yuan J, Cai B, Wang XL, Wu XL, Zhang YH, Zhang XY, Yin T, Zhu XH, et al. Association of body mass index and age with incident diabetes in Chinese adults: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;8(9):e021768.

Qin H, Chen Z, Zhang Y, Wang L, Ouyang P, Cheng L, Zhang Y. Triglyceride to high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ratio is associated with incident diabetes in men: A retrospective study of Chinese individuals. J Diabetes Invest. 2020;11(1):192–8.

Huh JH, Ahn SG, Kim YI, Go T, Sung KC, Choi JH, Koh KK, Kim JY. Impact of Longitudinal Changes in Metabolic Syndrome Status over 2 Years on 10-Year Incident Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Metab J. 2019;43(4):530–8.

Guerrero-Romero F, Simental-Mendia LE, Gonzalez-Ortiz M, Martinez-Abundis E, Ramos-Zavala MG, Hernandez-Gonzalez SO, Jacques-Camarena O, Rodriguez-Moran M. The product of triglycerides and glucose, a simple measure of insulin sensitivity Comparison with the euglycemic-hyperinsulinemic clamp. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(7):3347–51.

Rodriguez BL, Abbott RD, Fujimoto W, Waitzfelder B, Chen R, Masaki K, Schatz I, Petrovitch H, Ross W, Yano K, et al. The American Diabetes Association and World Health Organization classifications for diabetes: their impact on diabetes prevalence and total and cardiovascular disease mortality in elderly Japanese-American men. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(6):951–5.

Genuth S, Alberti KG, Bennett P, Buse J, Defronzo R, Kahn R, Kitzmiller J, Knowler WC, Lebovitz H, Lernmark A, et al. Follow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(11):3160–7.

Muka T, Asllanaj E, Avazverdi N, Jaspers L, Stringa N, Milic J, Ligthart S, Ikram MA, Laven JSE, Kavousi M, et al. Age at natural menopause and risk of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Diabetologia. 2017;60(10):1951–60.

Thong EP, Codner E, Laven JSE, Teede H. Diabetes: a metabolic and reproductive disorder in women. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(2):134–49.

Zhou BF. Cooperative Meta-Analysis Group of the Working Group on Obesity in C: Predictive values of body mass index and waist circumference for risk factors of certain related diseases in Chinese adults–study on optimal cut-off points of body mass index and waist circumference in Chinese adults. Biomed Environ Sci. 2002;15(1):83–96.

Liu LS. Writing Group of Chinese Guidelines for the Management of H: [2010 Chinese guidelines for the management of hypertension]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2011;39(7):579–615.

Joint committee issued Chinese guideline for the management of dyslipidemia in a: [2016 Chinese guideline for the management of dyslipidemia in adults]. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi 2016, 44(10):833–853.

Locateli JC, Lopes WA, Simoes CF, de Oliveira GH, Oltramari K, Bim RH, de Souza Mendes VH, Remor JM, Lopera CA, Nardo Junior N. Triglyceride/glucose index is a reliable alternative marker for insulin resistance in South American overweight and obese children and adolescents. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2019;32(10):1163–70.

Sitnik D, Santos IS, Goulart AC, Staniak HL, Manson JE, Lotufo PA, Bensenor IM. Fasting glucose levels, incident diabetes, subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular events in apparently healthy adults: a 12-year longitudinal study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2016;13(6):429–37.

Ligthart S, van Herpt TT, Leening MJ, Kavousi M, Hofman A, Stricker BH, van Hoek M, Sijbrands EJ, Franco OH, Dehghan A. Lifetime risk of developing impaired glucose metabolism and eventual progression from prediabetes to type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(1):44–51.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Funding

The present study was supported by grants provided by the natural science foundation of Hubei provincial department of education (D20182104), the scientific and technological project of Shiyan City of Hubei Province (16K67) and the initial project for post-graduates of Hubei University of Medicine (2016QDJZR08). All authors declare: no financial support from any organisation for the submitted work other than those listed above; no financial relationship with any companies that might have an interest in the submitted work; no non-financial interests or relationships that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Chenghu Huang, Chenhong Ren and Xiuping contributed to data collection, analysis, and writing of the manuscript. Yi Luo contributed to data analysis. Caibi Peng contributed to study design and writing of the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Human Research Ethics Committee approval was not required as all data used in the analysis were de-identified and publicly available.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Chenghu Huang, Chenhong Ren, Xiuping Xuan, Yi Luo and Caibi Peng have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

The curves of diabetes probability by FPG changes in different levels of sex (A), age (B), BMI (C), SBP (D), DBP (E), TC (F), TG (G), LDL (H), HDL (I) and history of diabetes (J). FPG changes was defined as the difference between the baseline and final visit FPG (FPG2) (mmol/L). BMI, body mass index; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; HDL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; SBP, systolic blood pressure; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Additional file 2: Figure S2.

The cumulative diabetes free probability by Kaplan-Meier survival curves in women (A), men (B) and overall (C). FPG changes was categorized into three stages based on the curves by two turning points: stage-1: < -0.24 mmol/L in women and < -0.05 mmol/L in men; stage-2: -0.24 - 1.15 women and -0.05 - 1.31 men; stage-3: > 1.16 women and > 1.32 men.

Additional file 3: Figure S3.

Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) of the product of FPG changes, TyG index and TG/HDL ratio for predicting the onset of diabetes in women (A), men (B) and all participants (C). BMI, body mass index; FPG, fasting plasma glucose; FPG changes were defined as the difference between baseline and final visit FPG (FPG2) (mmol/L); The triglyceride–high-density lipoprotein cholesterol concentration ratio (TG/HDL ratio) was counted by serum TG (mmol/L): HDL concentration (mmol/L) ratio; Triglyceride × fasting plasma glucose (TyG) index was calculated as the natural logarithm (Ln) of [TG (mg/dL) ⁎ glucose (mg/dL)/2].

Additional file 4: Table S1.

Baseline characteristic of participants according to sex.

Additional file 5: Supplemental Table 2.

The proportion of diagnosed diabetics in different stages of FPG changes and different genders.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, C., Ren, C., Xuan, X. et al. Nonlinear association between changes in fasting plasma glucose and the incidence of diabetes in a nondiabetic Chinese cohort. BMC Endocr Disord 22, 191 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-01094-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-022-01094-4