Abstract

Background

Retinol binding protein 4 (RBP4), a protein secreted by adipocytes and bound in plasma to transthyretin (TTR), has been associated with obesity, the early phase of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. The objective of this study was to elucidate the relationship between RBP4, TTR, triglyceride (TG) and type 2 diabetes risk in rural Thailand.

Methods

We measured the serum RBP4, TTR, glucose, triglyceride and insulin levels, and glucose tolerance of 167 volunteers from Sung Noen District, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Thailand. Student’s t-test, Pearson’s correlation and logistic regression analysis were used to evaluate the relationships between RBP4, TTR and type 2 diabetes markers.

Results

RBP4 and TTR levels, as well as homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) values, were significantly elevated among subjects with high triglyceride levels (p < 0.01, p < 0.05, p < 0.05, respectively). Triglyceride levels correlated with RBP4 (r = 0.34, p < 0.001) and TTR (r = 0.26, p < 0.01) levels, as well as HOMA-IR values (r = 0.16, p < 0.05). After adjustment for age and gender, the risk of hypertriglyceridemia was 3.7 times greater (95% CI =1.42–9.73, p = 0.008) in the highest RBP4 tertile as compared to the lowest tertile. Similarly, the highest TTR and HOMA-IR tertiles had greater risk of hypertriglyceridemia at 3.5 (95% CI = 1.30–9.20, p = 0.01) and 3.6 (95% CI = 1.33–9.58, p = 0.01) times higher than the respective lowest tertiles. The correlation between TTR and blood glucose was statistically significant (r = 0.18, p < 0.05), but not found this relationship in RBP4.

Conclusions

The associations of RBP4 and TTR with hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance may have important implications for the risk of heart disease and stroke.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Retinol binding protein (RBP4) is an adipokine that may be linked to type 2 diabetes (T2DM), which leads to cardiovascular disease (CVD). Several studies have reported elevated plasma RBP4 in T2DM subjects with obesity [1], impaired glucose tolerance [2,3,4], and T2DM with nephropathy [5]. RBP4 has also been found to affect the insulin signaling cascade, leading to insulin resistance. This adipokine is also associated with CVD, a complication induced by diabetes. While it has been shown that elevated serum RBP4 levels manifest in the development of systemic insulin resistance in rats [6], evidence for an effect of RBP4 on obesity and insulin resistance in humans is controversial. Studies have reported early states of T2DM with both increased and decreased levels of RBP4 [7,8,9,10]. Transthyretin (TTR), a transport protein, carries RBP4 and the thyroid hormone, thyroxin (T4), through the blood [11]. Recently, a human study found that circulatory RBP4 and TTR is associated with glucose intolerance and obesity, and T2DM and RBP4 is associated with insulin resistance [12].

Elevated plasma triglyceride (TG) concentration is a common biochemical finding associated with insulin resistance and is a valuable clinical marker of the metabolic syndrome. Observational and meta-analytic studies have shown relationships between increased cardiovascular risk and hypertriglyceridemia [13,14,15]. Numerous and complex cases of dyslipidemia, hypertension, hypercoagulability, and atherosclerosis are linked with insulin resistance. The inability of insulin-resistant fat cells to store TG is very likely the initial step in the development of the dyslipidemia. Based on in-vitro studies, short-term increases in insulin levels are associated with increased TG synthesis [16].

Metabolic syndrome consists of a clustering of several metabolic risk factors in an individual and is a major component of atherogenic dislipidemia, increased blood pressure, elevated glucose, and a prothrombotic state [17]. T2DM is a major public health problem in Thailand, with over 4 million cases of diabetes reported in 2015 [18, 19]. CVD has been the leading cause of death for over a decade and diabetes is likely to be an important factor in the vascular disease burden [20,21,22]. The objective of the present study was to investigate whether RBP4 and TTR are associated with insulin resistance, prediabetes and triglyceride levels in rural Thais with high T2DM risk.

Methods

Subjects

This cross-sectional study involved 167 participants aged between 35 and 66 years, from Sung Noen District, Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Thailand. Subjects were randomized and free of baseline T2DM and other any chronic diseases. Those pregnant, within a 6-month lactation period, or those regularly taking any medicine or having any infections, were excluded from the study. Informed consent was obtained from the subjects after explaining the study procedures in detail. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine (TMEC 13–073), Mahidol University.

Anthropometric assessment

Each subject was weighed (in kilograms) and measured for height (in meters) to evaluate individual body mass index (BMI, kg/m2). Waist circumference (WC) and hip circumference (HC) were measured and used to determine waist-to-hip ratio (WHR). A body composition monitor (model HBF-375, Omron Healthcare, Kyoto, Japan) was used to determine each subject’s body composition, including percentage of body fat (BF), visceral fat (VF), and muscle.

Measurement of laboratory parameters

Blood samples were taken from the antecubital veins after a fasting period of at least 12 h, and were used to assess fasting blood glucose (FBG), glycohemoglobin (HbA1c), fasting insulin, total cholesterol (TC), HDL-c and TG. Another blood sample was taken 2 h after a 75 g oral glucose load to determine glucose tolerance. Blood samples were centrifuged and blood serum was immediately frozen at 80 °C until analysis. FBG, HbA1c, 2-h blood glucose (2hBG), and TG were analyzed using a Cobas 6000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Basel, Switzerland). A human insulin ELISA kit (EMD Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) was used to measure fasting insulin levels. Insulin resistance was evaluated by the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) i.e. HOMA-IR = [Fasting insulin (μIU/mL) × Fasting glucose (mmol/L)] / 22.5.

TC and HDL-c were determined by enzymatic assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). Levels of TC, HDL-c, and TG were then used to calculate low density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c) using the Friedewald equation i.e. LDL-c = TC – (HDL-c + TG / 5). Serum RBP4 and TTR levels were assessed by non-commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using polyclonal rabbit anti-human antibodies (DakoCytomation, Hamburg, Germany), as previously described [23]. Both assays were calibrated using the standards obtained from human blood (N Protein Standard SL; Dade Behring, Marburg, Germany).

Dietary assessment

A validated semi-food frequency questionnaire (semi-FFQ) containing checklists of various food and beverages, food portion sizes, and consumption frequencies, was used to estimate dietary intake. Energy, protein, carbohydrate and fat intake were calculated using NutriSurvey software (version 2007; SEAMEO-TROPMED RCCN, University of Indonesia).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS (version 15.0; SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA), with results expressed as mean and standard deviation. A Student’s t-test was performed to compare the means between the two groups. Correlations among variables were calculated using Pearson’s correlation with the associations estimated using odd ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) obtained from logistic regression. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Biometric and biochemical characteristics of the study groups

The study participants were divided into two groups according to TG level using a 150 mg/dl cut-off point [24]. The group with normal TG levels (TG < 150 mg/dl) contained 110 subjects, with the remaining 57 subjects positive for hypertriglyceridemia (TG ≥ 150 mg/dl). A comparison of age, BMI, WC, HC, WHR, BF, VF, and muscle between normal and high TG subjects is shown in Table 1. Normal and high TG subjects were in the same age range. Body size and composition, measured by BMI, HC, WHR, BF, and muscle, showed no significant differences between normal and high TG groups. Conversely, the central obesity indicators WC and VF were significantly elevated in the high TG group (p < 0.05). Likewise, the high TG group had higher diastolic blood pressure readings than the normal TG group (p = 0.03), though there were no significant differences between groups for systolic blood pressure, FBG, 2hBG, and HbA1c. Regarding lipid profiles, there were no significant differences in TC, HDL-c, or LDL-c between the normal and high TG groups. The results from the semi-FFQ showed that the normal- and high TG groups had similar dietary intake patterns. The average energy intake of the normal TG group was 2404.82 kcal/day, and of the high TG group 2382.24 kcal/day, with carbohydrates constituting the highest proportion by weight (Table 2).

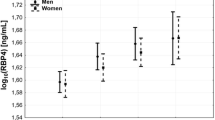

Increased RBP4 and TTR levels and HOMA-IR values in the high TG group

Serum RBP4 and TTR were significantly elevated in the high TG group (p < 0.05) (Fig. 1a, b). HOMA-IR values corresponded to the levels of RBP4 and TTR, with the high TG group showing higher HOMA-IR values than the normal TG group (p = 0.02) (Fig. 1c). Significant positive correlations were found between serum TG and RBP4 (r = 0.34, p = 0.000), TTR (r = 0.26, p = 0.001), and HOMA-IR (r = 0.16, p = 0.039).

The risk of hypertriglyceridemia was evaluated by multivariate analysis (Table 3). Fasting RBP4 and TTR levels were divided into tertiles, with the lowest tertile being the reference tertile. The results showed that after adjustment for age and gender, individuals with RBP4 levels in the highest tertile had 3.7 times higher risk of developing hypertriglyceridemia than those in the lowest tertile (OR = 3.71, 95% CI = 1.42–9.73). Similarly, subjects in the highest TTR and HOMA-IR tertiles had 3.5 times (OR = 3.46, 95% CI = 1.30–9.20) and 3.6 times (OR = 3.58, 95% CI = 1.33–9.58) higher risk of developing hypertriglyceridemia, respectively, than those in the lowest tertiles.

Association of RBP4, TTR, and HOMA-IR with serum glucose

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess the relationship between blood glucose and study parameters. Blood glucose showed a non-significant positive correlation with most of the study parameters, including WHR (r = 0.031), systolic (r = 0.194) and diastolic (r = 0.112) blood pressure, VF (r = 0.036), muscle (r = 0.098), TC (r = 0.025), LDL-c (r = 0.001), and HDL-c (r = 0.095). To investigate T2DM risk, the study subjects were divided into two groups based on FBG, i.e. normal T2DM risk group (FBG < 100 mg/dl) and high T2DM risk group (FBG≥100 mg/dl). The high T2DM risk group showed increased TTR levels (p = 0.02) and HOMA-IR values (p = 0.03), as well as decreased RBP4 levels (p = 0.04) than the normal T2DM risk group (Table 4).

Correlation between RBP4, TTR, and HOMA-IR with metabolic syndrome parameters

Pearson correlation coefficients were used to assess the relationship between RBP4, TTR, and HOMA-IR, with metabolic syndrome parameters. There were many statistically significant correlations between RBP4, TTR, and HOMA-IR, with metabolic syndrome parameters including RBP4 correlated with TG (r = 0.344) and HDL-c (r = 0.259); TTR correlated with FBG (r = 0.182), TG (r = 0.260), and HDL-c (r = 0.168) was also significant; HOMA-IR correlated with FBG (r = 0.216), TG (r = 0.160), and HDL-c (r = 0.186). RBP4 showed a negative correlation with FBG (r = − 0.057) and a positive correlation with HOMA-IR (r = 0.134), but without statistical significance. TTR was also found to be non-statistically significant with HOMA-IR (r = − 0.046). However, the correlation between TTR and FBG was statistically significant (r = 0.182).

Discussion

The subjects with hypertriglyceridemia in this study presented a higher risk of metabolic syndrome due to their above normal TG levels and abdominal obesity indicator values (WC and VF). These subjects may also have increased insulin resistance, since they showed increased HOMA-IR values. Many other investigators have reported that hypertriglyceridemia is closely related to an insulin resistant state. Patients with primary hypertriglyceridemia have increased non-esterified fatty acid turnover rates and secretion by adipose tissue, supplying an excess of fatty acids to the liver for synthesis of TG. This increase suggests that patients with hypertriglyceridemia have insulin resistance at the level of the adipose tissues [25,26,27]. Björntorp suggests that abdominal obesity is closely linked to insulin resistance, because the mobilized TG in visceral fat creates large amounts of free fatty acid in the portal vein, which can affect liver function and lead to hypertriglyceridemia [28].

There is evidence to suggest that RBP4 and TTR play a role in the development of insulin resistance [1, 12, 29] and metabolic syndrome [30,31,32]. RBP4 was found to interrupt the insulin signaling cascade causing insulin resistance. In addition, relationships have been found between RBP4 and diabetes complications, such as atherosclerosis and CVD [6]. Several studies have investigated the association of RBP4 with T2DM risk, however the results are conflicting. In a cross-sectional study by Comucci et al., Brazilian subjects with T2DM showed lower RBP4 levels than the control group, though RBP4 was not related to T2DM [33]. TTR functions as a carrier for RBP4, and since hepatic secretion of TTR is affected by dietary protein and energy intake, TTR is also used as a biomarker for assessing nutritional status [34]. TTR levels were reported to be elevated in T2DM subjects and to correlate positively with TG level [30]. Pandey et al. have shown higher circulatory levels of RBP4 and TTR in T2DM subjects, as well as a significant association between T2DM and RBP4 (OR = 1.11, 95% CI: 1.01–1.21) and TTR (OR = 1.34, 95% CI: 1.17–1.55) after adjusting for confounding factors [12]. In the present study, subjects with FBG ≥100 mg/dl had significantly lower serum levels of RBP4 and higher levels of TTR than those with FBG < 100 mg/dl. Moreover, a significant correlation was found between FBG and TTR levels (p = 0.018), although the results for a correlation between FBG and RBP4 levels were inconclusive. Moreover, a relationship between RBP4, TTR and metabolic syndrome components was found in this study. Classified by TG level, subjects with high TG showed increased RBP4 and TTR levels, as well as increased HOMA-IR values. In addition, the risk of hypertriglyceridemia was approximately 4-fold greater in subjects with high serum RBP4 and TTR levels and HOMA-IR values. An association between increased levels of both RBP4 and TTR and an elevated risk of insulin resistance (the precursor state to T2DM) and CVD (the macrovascular complication of diabetes) has been reported in several studies [1, 2, 35]. A positive correlation has also been found between plasma RBP4 and TG levels in subjects with T2DM [7, 35, 36]. Hypertriglyceridemia has been independently associated with an elevated risk of CVD [37, 38]. However, while associations between plasma RBP4 levels, TG levels and insulin resistance have been shown in many human studies, while other studies report an insulin resistance-independent association between plasma RBP4 and TG levels [7, 9]. Nevertheless, the results of the present study suggest associations between RBP4, TTR, TG, and insulin resistance. In particular, our results indicate that TTR may play a role in the pathophysiology of diabetic hypertriglyceridemia.

Conclusions

The relationships between RBP4 and TTR levels and FBG abnormalities in this study remain ambiguous. Conversely, our results show a significant association between serum TG levels and insulin resistance. TTR was associated with prediabetes and TG level, whereas RBP4 was only associated with TG. Our findings indicated that RBP4 and TTR are related to hypertriglyceridemia and insulin resistance; therefore, these markers may involve the risk of heart disease and stroke. However, the cross-sectional nature of this study means that these associations reflect a single time point only. A cohort study is therefore required to confirm the associations of these markers with blood glucose and serum TG levels.

Abbreviations

- 2hBG:

-

2-h blood glucose

- 95% CI:

-

95% confidence intervals

- BF:

-

Body fat

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- HC:

-

Hip circumference

- HDL-c:

-

High density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HOMA-IR:

-

The homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance

- LDL-c:

-

Low density lipoprotein cholesterol

- p :

-

p-value

- r:

-

Regression coefficient

- RBP4:

-

Retinol binding protein 4

- Semi-FFQ:

-

Semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TTR:

-

Transthyretin

- VF:

-

Visceral fat

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHR:

-

Waist to hip ratio

References

Graham TE, Yang Q, Blüher M, Hammarstedt A, Ciaraldi TP, Henry RR, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 and insulin resistance in lean, obese, and diabetic subjects. New Engl J Med. 2006;354:2552–63.

Cho YM, Youn BS, Lee H, Lee N, Min SS, Kwak SH, et al. Plasma retinol-binding protein-4 concentrations are elevated in human subjects with impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:2457–61.

Chavez AO, Coletta DK, Kamath S, Cromack DT, Monroy A, Folli F, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with impaired glucose tolerance but not with whole body or hepatic insulin resistance in Mexican Americans. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;296:E758–64.

Xu M, Li XY, Wang JG, Wang XJ, Huang Y, Cheng Q, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with impaired glucose regulation and microalbuminuria in a Chinese population. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1511–9.

Murata M, Saito T, Otani T, Sasaki M, Ikoma A, Toyoshima H, et al. An increase in serum retinol-binding protein 4 in the type 2 diabetic subjects with nephropathy. Endocr J. 2009;56:287–94.

Li F, Xia K, Sheikh MS, Cheng J, Li C, Yang T. Retinol binding protein 4 promotes hyperinsulinism induced proliferation of rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014;9:1634–40.

von Eynatten M, Lepper PM, Liu D, Lang K, Baumann M, Nawroth PP, et al. Retinol-binding protein 4 is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome, but not with insulin resistance, in men with type 2 diabetes or coronary artery disease. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1930–7.

Kowalska I, Straczkowski M, Adamska A, Nikolajuk A, Karczewska-Kupczewska M, Otziomek E, et al. Serum retinol binding protein 4 is related to insulin resistance and nonoxidative glucose metabolism in lean and obese women with normal glucose tolerance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2786–9.

Lewis JG, Shand BI, Frampton CM, Elder PA, Scott RS. Plasma retinol-binding protein is not a marker of insulin resistance in overweight subjects: a three year longitudinal study. Clin Biochem. 2008;41:1034–8.

Gavi S, Qurashi S, Stuart LM, Lau R, Melendez MM, Mynarcik DC, et al. Influence of age on the association of retinol-binding protein 4 with metabolic syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16:893–5.

Zanotti G, Berni R. Plasma retinol-binding protein: structure and interactions with retinol, retinoids, and transthyretin. Vitam Horm. 2004;69:271–95.

Pandey GK, Balasubramanyam J, Balakumar M, Deepa M, Anjana RM, Abhijit S, et al. Altered circulating levels of retinol binding protein 4 and transthyretin in relation to insulin resistance, obesity, and glucose intolerance in Asian Indians. Endocr Pract. 2015;21:861–9.

Patel A, Barzi F, Jamrozik K, Lam TH, Ueshima H, Whitlock G, et al. Serum triglycerides as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases in the Asia-Pacific region. Circulation. 2004;110:2678–86.

Sarwar N, Danesh J, Eiriksdottir G, Sigurdsson G, Wareham N, Bingham S, et al. Triglycerides and the risk of coronary heart disease: 10,158 incident cases among 262,525 participants in 29 western prospective studies. Circulation. 2007;115:450–8.

Murad MH, Hazem A, Coto-Yglesias F, Dzyubak S, Gupta S, Bancos I, et al. The association of hypertriglyceridemia with cardiovascular events and pancreatitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Endocr Disord. 2012;12:2.

Henry N. Ginsberg. Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:453–8.

Grundy SM. Hypertriglyceridemia, atherogenic dyslipidemia, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1998;81:18B–25B.

International Diabetes Federation. Diabetes atlas, 7th edition. 2017. www.idf.org/diabetesatlas. Accessed 21 June 2017.

International Diabetes Federation. WP Region. 2017. https://www.idf.org/our-network/regions-members/western-pacific/members/115-thailand.html. Accessed 21 June 2017.

World Health Organization. Cardiovascular disease. 2017. http://www.who.int/cardiovascular_diseases/en/. Accessed 21 June 2017.

World Health Organization. Noncommunicable Diseases (NCD) Country Profiles. 2014. http://www.who.int/nmh/countries/tha_en.pdf. Accessed 21 June 2017.

National Institutes of Health. Metabolic Syndrome. 2017. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/ms. Accessed 21 June 2017.

Raila J, Henze A, Spranger J, Mohlig M, Pfeiffer AFH, Schweigert FJ. Microalbuminuria is a major determinant of elevated plasma retinol-binding protein 4 in type 2 diabetic patients. Kidney Int. 2007;72:505–11.

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (adult treatment panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106:3143–421.

Grundy SM. Hypertriglyceridemia, insulin resistance, and the metabolic syndrome. Am J Cardiol. 1999;83(9B):25F–9F.

Steiner G. Hyperinsulinaemia and hypertriglyceridaemia. J Intern Med Suppl. 1994;736:23–6.

Despres JP. The insulin resistance-dyslipidemic syndrome of visceral obesity: effect on patients’ risk. Obes Res. 1998;6:8S–17S.

Bjorntorp P. New concepts in the relationship obesity--non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus. Eur J Med. 1992;1:37–42.

Saki F, Ashkani-Esfahani S, Karamizadeh Z. Investigation of the relationship between retinol binding protein 4, metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in Iranian obese 5-17 year old children. Iran J Pediatr. 2013;23:396–402.

Yoshida A, Matsutani Y, Fukuchi Y, Saito K, Naito M. Analysis of the factors contributing to serum retinol binding protein and transthyretin levels in Japanese adults. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2006;13:209–15.

Qi Q, Yu Z, Ye X, Zhao F, Huang P, Hu FB, et al. Elevated retinol-binding protein 4 levels are associated with metabolic syndrome in Chinese people. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:4827–34.

Mostafaie N, Sebesta C, Zehetmayer S, Jungwirth S, Huber KR, Hinterberger M, et al. Circulating retinol-binding protein 4 and metabolic syndrome in the elderly. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2011;161:505–10.

Comucci EB, Vasques AC, Geloneze B, Calixto AR, Pareja JC, Tambascia MA. Serum levels of retinol binding protein 4 in women with different levels of adiposity and glucose tolerance. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol. 2014;58:709–14.

Ingenbleek Y, Young V. Transthyretin (prealbumin) in health and disease: nutritional implications. Annu Rev Nutr. 1994;14:495–533.

Takebayashi K, Suetsugu M, Wakabayashi S, Aso Y, Inukai T. Retinol binding protein-4 levels and clinical features of type 2 diabetes patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2712–9.

Cabré A, Lázaro I, Girona J, Manzanares JM, Marimón F, Plana N, et al. The APOA5-1131 T>C variant enhances the association between RBP4 and hypertriglyceridemia in diabetes. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2010;20:243–8.

West KM, Ahuja MM, Bennett PH, Czyzyk A, De Acosta OM, Fuller JH, et al. The role of circulating glucose and triglyceride concentrations and their interactions with other “risk factors” as determinants of arterial disease in nine diabetic population samples from the WHO multinational study. Diabetes Care. 1983;6:361–9.

Fontbonne A, Eschwège E, Cambien F, Richard JL, Ducimetière P, Thibult N, et al. Hypertriglyceridaemia as a risk factor of coronary heart disease mortality in subjects with impaired glucose tolerance or diabetes. Results from the 11-year follow-up of the Paris prospective study. Diabetologia. 1989;32:300–4.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at Nong Waeng Promoting Hospital, Thailand and our laboratory-based colleagues from the Institute of Nutritional Science of the University of Potsdam, Germany, especially Ms. Undine Ullrich-Schaare. We also thank our subjects for their participation in our study, and Alice Tait, PhD, from Edanz Group, Mr. Robert Sine and Mr. Paul Adams from ORS, Faculty of Tropical Medicine for English editing of this manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by Mahidol University and Katholischer Akademischer Ausländer-Dienst (KAAD).

Availability of data and materials

The dataset supporting the conclusions of this article has not been deposited in any public repository but is available to researchers from the corresponding author upon request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KK, PP, CP, NC, NW, SP, RA, IH, FS designed the study. KK, PP, CP, NC, NW, SP, obtained data. KK and PP analyzed and interpreted data. KK, PP, CP, NC, NW, SP, RA, IH, FS provided advice. KK wrote the first draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Tropical Medicine, Mahidol University (TMEC 13–073).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Kwanbunjan, K., Panprathip, P., Phosat, C. et al. Association of retinol binding protein 4 and transthyretin with triglyceride levels and insulin resistance in rural thais with high type 2 diabetes risk. BMC Endocr Disord 18, 26 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-018-0254-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12902-018-0254-2