Abstract

Background

For more than forty years, graftectomy has been the standard treatment of spontaneous renal transplant rupture. However, recent evidences suggest that graft salvage strategies can be safely pursued, even in difficult cases.

Case presentation

We report on a thirty-nine-year-old woman who received a deceased donor kidney transplant and experienced spontaneous allograft rupture due to acute rejection. The rupture was further complicated by urinary leakage. The kidney and the ureter were successfully repaired. Eight years after transplantation, graft function is still excellent.

Conclusion

Due to the lack of transplantable organs and the long time usually spent on the waiting list, graftectomy should be only considered in case of refractory haemodynamic instability or compromised graft viability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Spontaneous renal allograft rupture is a rare but life threatening complication of kidney transplantation. Graftectomy is the safest option. However, if the patient can be stabilised, graft repair should be always considered because of the long waiting list and the low chance of receiving a second transplant.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report on a patient who had her transplant saved after experiencing acute rejection, spontaneous graft rupture and urinary leakage.

Case presentation

A thirty-nine-year-old woman with end stage renal disease secondary to eclampsia was admitted to our institution for her primary deceased donor kidney transplantation on January 2006. Pre-transplant comorbidities included hypertension, dyslipidemia and secondary hyperparathyroism. The donor was a twenty-six-year-old male who died from acute obstruction of the foramina of Monroe. Cold ischemia time was ten hours. The kidney was medium-sized, had one artery, one vein and one ureter. The donor and the recipient were blood group compatible and six HLA antigens mismatched. The highest recipient Panel Reactivity Antibody was 15 % and the direct microcytotoxicity crossmatch was negative. Macroscopically, the kidney looked normal. It was extraperitoneally transplanted in the left iliac fossa, as standard procedure. After declamping, the organ reperfused immediately. The graft ureter was anastomosed to the bladder according to the single stitch technique. The patient was enrolled in a phase III randomized, multicenter, clinical trial and received basiliximab (Simulect®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation), cyclosporine (Sandimmune Neoral®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation), everolimus (Certican®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation) and steroids.

The early post-operative course was complicated by delayed graft function requiring haemodialysis. According to the protocol, her baseline immunosuppression was not changed. Daily ultrasound evaluation showed a well-sized graft with no fluid collections, no hydronephrosis, and good intra-parenchymal flow. Haematologic and coagulation profiles were normal.

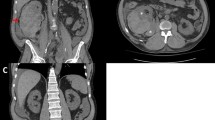

On post-operative day four, the recipient suddenly complained of abdominal pain and the urinary output dropped. Blood pressure, pulse rate and haemoglobin concentration remained stable. Four hours later, the abdominal pain increased and the area over the graft became distended and tender. Hypotension rapidly developed, the pulse rate increased and the patient became anuric. Aggressive resuscitation was promptly initiated. An urgent Doppler ultrasound scan was performed. It showed a large hypoechoic collection surrounding the graft with good flow in the renal artery and a patent renal vein. Subsequent contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed a ruptured graft and a massive retroperitoneal haematoma with active bleeding from the transplanted kidney (Fig. 1). The patient was immediately brought to theatre and explored. A large peri-graft haematoma was evacuated. The kidney was swollen but pink and the arterial pulse was good. A 5 cm long and 1.5 cm deep laceration was found along the middle portion of the convex border of graft, actively bleeding. After en block clamping of the renal vessels, the transplant was fully inspected. Haemostasis was achieved using a haemostatic matrix (Floseal® Hemostatic Matrix, Baxter International Inc.) and by apposition of several mattress polyglactin 910 (Vicryl™, Ethicon Inc.) sutures tied over flaps of absorbable hemostats (Surgicel® Original Absorbable Hemostat, Ethicon Inc.). To prevent extension of the rupture, a polyglactin 910 mesh (Vicryl™ Woven Mesh, Ethicon Inc.) was wrapped around the graft. The procedure took 140 min and renal clamping was 45 min. The total intra-operative blood loss (including the haematoma) was 500 mL and two units of packed red blood cells were transfused. Considering the severity of the bleeding, the complex repair, and the risk of further damage to the kidney, a graft biopsy was not taken at the time of the operation. However, the clinical picture was highly suggestive of acute rejection and we therefore decided to administer a course of rabbit anti-thymocyte globulins (Thymoglobulin®, Genzyme Inc.). Cyclosporine and everolimus were also switched to tacrolimus (Prograf®, Astellas Pharma Inc.) and mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept®, Genentech USA Inc.). After the operation, the patient remained anuric requiring haemodialysis for twenty-one days. Renal function improved and serum creatinine concentration fell to 2 mg/dL.

On post-operative day fifty-two, clear fluid started to seep from the wound. Urgent CT scan showed a large (5 × 2.3 cm) fluid collection in continuity with the area of the previous rupture (Fig. 2). Urinary leakage was confirmed by chemical analysis of the fluid. A nephrostomy tube and a trans-abdominal drain were inserted to control the leak and evacuate the collection. Two days later, the patient became febrile and the urinary output dropped. A nephrostogram was performed. It demonstrated another urinary leak at the site of the ureteral anastomosis (Fig. 3). Following an unsuccessful simultaneous cystoscopy and fluoroscopy guided ureteral stent placement, a surgical exploration was planned. The abdomen was entered through a midline incision and the graft was inspected. The distal part of the transplanted ureter, partially necrotized, was resected and the proximal stump was anastomosed to the bladder according to the Lich-Gregoire technique. A double-J pyeloureteral stent was placed to protect the anastomosis. The procedure took 143 min. The post-operative course was uneventful. Renal function gradually recovered, serum creatinine fell to 1.7 mg/dL and the patient was eventually discharged.

Eight years after transplantation, the patient is doing well and her serum creatinine is 1 mg/dL.

Discussion

Spontaneous renal allograft rupture is defined as a laceration of the renal capsule when there are no other identifiable injuries noted at the time of the organ retrieval [1]. Its incidence has been reported as between 0.3 and 9.6 %, depending on the series [2–4]. This complication usually occurs within the first two weeks after transplantation although late ruptures have been reported [5].

Several causes have been proposed [1–3, 5–7]. Acute rejection is the most important, accounting for 60 to 80 % of cases. Less frequent etiologies include renal vein thrombosis, acute tubular necrosis, ureteral obstruction, renal biopsy, trauma, local ischaemia, septic infarction and cancer. The rupture most frequently occurs longitudinally, along the convex border of the kidney. Clinical presentation is often typical, with severe graft dysfunction and acute blood loss. Immediate ultrasound evaluation can rapidly and safely confirm the diagnosis with 87 % sensitivity and 100 % specificity [8].

In case of haemodynamic instability, immediate surgical exploration is mandatory. Initial reports of conservative management of graft rupture showed poor results, with less than 30 % success rate. Failure to control acute bleeding, inability to reverse acute rejection, post-surgical development of multiple organ failure and uncontrollable coagulopathy were the main causes of the high rate of graft nephrectomies observed. In the last decades, improved surgical technique and post-operative care have significantly reduced transplant-related mortality and morbidity. Complex operations are now safely performed with good results. Current reports demonstrate that ruptured grafts can be saved with a success rate as high as 80 %. Moreover, recipients undergoing successful repair have long-term outcomes similar to the general transplant population. Recurrent rupture, the most dangerous complication of graft repair, only occurs in 5 % of patients and does not significantly jeopardise the prognosis (see Table 1 for details). Fibrin glue and collagen foam can be used to facilitate haemostasis without endangering the transplant through unnecessary manipulation of oedematous and fragile tissues [9]. Renal corsetage with various materials, including polyglactin 910 mesh, lyophilized dura, grafts of peritoneum, pieces of external oblique aponeurosis and polypropylene mesh has also been reported [10]. In this setting, external compression is particularly helpful because it supports haemostasis and at the same time prevents further extension of the rupture.

Conclusions

When spontaneous renal transplant rupture occurs, nephrectomy is justified only in case of refractory haemodynamic instability or compromised kidney viability. When irreversible graft damage can be ruled out and the patient can be readily resuscitated, transplant salvage should always be attempted.

Consent

Written informed consent for publication of this Case report and any accompanying images has been obtained from the patient. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

References

Richardson AJ, Higgins RM, Jaskowski AJ, Murie JA, Dunnill MS, Ting A, et al. Spontaneous rupture of renal allografts: the importance of renal vein thrombosis in the cyclosporine era. Br J Surg. 1991;77:558–60.

Hochleitner BW, Kafka R, Spechtenhauser B, Bösmüller C, Steurer W, Königsrainer A, et al. Renal allograft rupture is associated with rejection or acute tubular necrosis, but not with renal vein thrombosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2001;16:124–7.

Azar GJ, Zarifian A, Frentz GD, Tesi RJ, Etheredge EE. Renal allograft rupture: a clinical review. Clin Transplant. 1996;10:635–8.

Heimbach D, Miersch WD, Buszello H, Schoeneich G, Kleht HU. Is the transplant-preserving management of renal allograft rupture justified? Br J Urol. 1995;75:729–32.

Finley DS, Roberts JP. Frequent salvage of ruptured renal allografts: a large single center experience. Clin Transplant. 2003;17:126–9.

Chan YH, Wong KM, Lee KC, Li CS. Spontaneous renal allograft rupture attributed to acute tubular necrosis. Am J Kidney Dis. 1999;34:355–8.

Szenohradszky P, Smehak G, Szederkenyi E, Marofka F, Csajbok E, Morvay Z, et al. Renal allograft rupture: a clinicopathologic study of 37 nephrectomy cases in a series of 628 consecutive renal transplants. Transplant Proc. 1999;31:2107–11.

Soler R, Perez-Fontan FJ, Lago M, Moncalian J, Perez-Fontan M. Renal allograft rupture: diagnostic role of ultrasound. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1992;7:871–4.

Hanke P, Fassbinder W, Brox G. Treatment of spontaneous kidney allograft rupture by means of fibrin sealant and collagen fleece: experimental and clinical studies. Transplant Proc. 1986;18:1029–33.

Said R, Duarte R, Chaballout A, Boghdadly SE, Nezamuddin N, Mattoo T. Spontaneous rupture of renal allograft. Urology. 1994;43:554–5.

Murray JE, Wilson RE, Tilney NL, Merrill JP, Cooper WC, Birtch AG, et al. Five years' experience in renal transplantation with immunosuppressive drugs: survival, function, complications, and the role of lymphocyte depletion by thoracic duct fistula. Ann Surg. 1968;168:416–35.

Salaman JR, Calne RY, Pena J, Sells RA, White HJ, Yoffa D. Surgical aspects of clinical renal transplantation. Br J Surg. 1969;56:413–7.

Siedek M. Observations in rejections of kidney transplants. Langenbecks Arch Surg. 1969;325:714–9.

Flanigan WJ, Caldwell FT, Williams GD, Brewer TE, Glenn WE, Headstream JW, et al. Clinical patterns of renal allograft rejection. Ann Surg. 1971;173:733–47.

Haimov M, Glabman S, Burrows L. Spontaneous rupture of the allografted kidney. Arch Surg. 1971;103:510–2.

Lord RS, Effeney DJ, Hayes JM, Tracy GD. Renal allograft rupture: cause, clinical features and management. Ann Surg. 1973;177:268–73.

Minale C, Linder E, Largiader F. Spontaneous rupture of a transplanted kidney. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 1972;97:459–61.

Ghose MK, Kest LM, Cohen SM, Roza O, Berman LB, Lidsky I, et al. Spontaneous rupture of renal allotransplants. J Urol. 1973;109:790–5.

Fjeldborg O, Kim CH. Spontaneous rupture of renal transplant. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1974;8:31–6.

Kootstra G, Meijer S, Elema JD. "Spontaneous" rupture of homografted kidneys. Arch Surg. 1974;108:107–12.

Homan WP, Cheigh JS, Kim SJ, Mouradian J, Tapia L, Riggio RR, et al. Renal allograft fracture: clinicopathological study of 21 cases. Ann Surg. 1977;186:700–3.

Van Cangh PJ, Ehrlich RM, Smith RB. Renal rupture after transplantation. Urology. 1977;9:8–10.

Brekke I, Flatmark A, Laane B, Mellbye O. Renal allograft rupture. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1978;12:265–70.

Montes F, McMaster P, Calne RY, Evans DB. Rupture of the allografted kidney--is repair possible? Proc Eur Dial Transplant Assoc. 1978;15:378–83.

Susan LP, Braun WE, Banowsky LH, Straffon RA, Valenzuela R. Ruptured human renal allograft. Pathogenesis and management Urology. 1978;11:53–7.

Dryburgh P, Porter KA, Krom RA, Uchida K, West JC, Weil 3rd R, et al. Should the ruptured renal allograft be removed? Arch Surg. 1979;114:850–2.

Prompt CA, Johnson WH, Ehrlich RM, Lee DB, Smith RB, Schultze RG. Nontraumatic rupture of renal allografts. Urology. 1979;13:145–8.

Oesterwitz H, Tulatz A, Scholz D, May G. Spontaneous rupture of cadaver kidney allotransplants: how successful is a repair? Report of 22 cases and review of the literature. Eur Urol. 1980;6:284–8.

van der Vliet JA, Kootstra G, Tegzess AM, Meijer S, Krom RA, Slooff MJ, et al. Management of rupture in allografted kidneys. Neth J Surg. 1980;32:45–8.

Goldman M, De Pauw L, Kinnaert P, Vereerstraeten P, Van Geertruyden J, Toussaint C. Renal allograft rupture: possible causes and results of surgical conservative management. Transplantation. 1981;32:153–6.

Nghiem DD, Goldman MH, Mendez-Picon G, Rao KG, Woodlief RM, Fields WR, et al. Noninvasive assessment of the transplanted kidney: ultrasound vs. computerized tomography. Am Surg. 1981;47:492–4.

Thukral R, Mir AR, Jacobson MP. Renal allograft rupture: a report of three cases and review of the literature. Am J Nephrol. 1982;2:15–27.

Serrallach N, Gutierrez R, Serrate R, Aguilo F, Munoz J, Franco E, et al. Renal allograft rupture: surgical treatment by renal corsetage with lyophilized human dura. J Urol. 1985;133:452–5.

Chopin DK, Abbou CC, Lottmann HB, Popov Z, Lang PR, Buisson CL, et al. Conservative treatment of renal allograft rupture with polyglactin 910 mesh and gelatin resorcin formaldehyde glue. J Urol. 1989;142:363–5.

Yadav RV, Sinha R. Graft repair: the treatment of choice for renal allograft rupture. J Urol. 1994;151:1498–9.

Zadrozny D, Pirski MI, Draczkowski T, Gacyk W. The treatment of renal allograft rupture. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:156.

Pontones Moreno JL, Rodrigo Aliaga M, Monserrat Monfort JJ, Guillen Navarro M, Sanchez Plumed J, Jimenez Cruz JF. Post-transplantation renal rupture. Actas Urol Esp. 1998;22:840–5. discussion 6.

Millwala FN, Abraham G, Shroff S, Soundarajan P, Rao R, Kuruvilla S. Spontaneous renal allograft rupture in a cohort of renal transplant recipients: a tertiary care experience. Transplant Proc. 2000;32:1912–3.

Ramos M, Martins L, Dias L, Henriques AC, Soares J, Queiros J, et al. Renal allograft rupture: a clinicopathologic review. Transplant Proc. 2000;32:2597–8.

Guleria S, Khazanchi RK, Dinda AK, Aggarwal S, Gupta S, Bhowmik D, et al. Spontaneous renal allograft rupture: is graft nephrectomy an option? Transplant Proc. 2003;35:339.

He B, Rao MM, Han X, Li X, Guan D, Gao J. Surgical repair of spontaneous renal allograft rupture: a new procedure. ANZ J Surg. 2003;73:381–3.

Busi N, Capocasale E, Mazzoni MP, Benozzi L, Valle RD, Cambi V, et al. Spontaneous renal allograft rupture without acute rejection. Acta Biomed. 2004;75:131–3.

Risaliti A, Sainz-Barriga M, Baccarani U, Adani GL, Montanaro D, Gropuzzo M, et al. Surgical complications after kidney transplantation. G Ital Nefrol. 2004;21 Suppl 26:S43–7.

Sanchez de la Nieta MD, Sanchez-Fructuoso AI, Alcazar R, Perez-Contin MJ, Prats D, Grimalt J, et al. Higher graft salvage rate in renal allograft rupture associated with acute tubular necrosis. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:3016–8.

Shahrokh H, Rasouli H, Zargar MA, Karimi K, Zargar K. Spontaneous kidney allograft rupture. Transplant Proc. 2005;37:3079–80.

Martinez Mansur R, Piana M, Codone J, Elizalde F, Diez M, Duro J, et al. The rupture of the renal graft. Arch Esp Urol. 2006;59:489–92.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lauren Sarah Harris (MS, Barts and The London School of Medicine - London, UK) who kindly provided language revision.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

EF collected data, reviewed the literature and drafted the manuscript. SI reviewed the literature, drafted the manuscript and formatted the text for submission. AC collected, analyzed and interpreted data. FC revised the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Favi, E., Iesari, S., Cina, A. et al. Spontaneous renal allograft rupture complicated by urinary leakage: case report and review of the literature. BMC Urol 15, 114 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-015-0109-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12894-015-0109-3