Abstract

Background & aims

Complications after laparoscopic liver resection (LLR) are important factors affecting the prognosis of patients, especially for complex hepatobiliary diseases. The present study aimed to evaluate the value of a three-dimensional (3D) printed dry-laboratory model in the precise planning of LLR for complex hepatobiliary diseases.

Methods

Patients with complex hepatobiliary diseases who underwent LLR were preoperatively enrolled, and divided into two groups according to whether using a 3D-printed dry-laboratory model (3D vs. control group). Clinical variables were assessed and complications were graded by the Clavien-Dindo classification. The Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI) scores were calculated and compared for each patient. Multivariable analysis was performed to determine the risk factors of postoperative complications.

Results

Sixty-two patients with complex hepatobiliary diseases underwent the precise planning of LLR. Among them, thirty-one patients acquired the guidance of a 3D-printed dry-laboratory model, and others were only guided by traditional enhanced CT or MRI. The results showed no significant differences between the two groups in baseline characters. However, compared to the control group, the 3D group had a lower incidence of intraoperative blood loss, as well as postoperative 30-day and major complications, especially bile leakage (all P < 0.05). The median score on the CCI was 20.9 (range 8.7–51.8) in the control group and 8.7 (range 8.7–43.4) in the 3D group (mean difference, -12.2, P = 0.004). Multivariable analysis showed the 3D model was an independent protective factor in decreasing postoperative complications. Subgroup analysis also showed that a 3D model could decrease postoperative complications, especially for bile leakage in patients with intrahepatic cholelithiasis.

Conclusion

The 3D-printed models can help reduce postoperative complications. The 3D-printed models should be recommended for patients with complex hepatobiliary diseases undergoing precise planning LLR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Minimally invasive and precision therapies comprise the new direction of surgery in the 21st century. Since the first laparoscopic liver tumor resection was reported by Reich et al. in 1991 [1], laparoscopic technology has become increasingly widely used in the diagnosis and treatment of hepatobiliary diseases. Multiple meta-analyses have shown that precise liver resection for primary liver cancer is correlated with less trauma, faster recovery, and better prognosis than conventional liver resection. However, there are still great difficulties in applying minimally invasive and precise treatment for complex hepatobiliary diseases because it is difficult to expose certain parts of the liver or remove complex hepatobiliary lesions under laparoscopy. In addition, the liver has a complex anatomical structure and may bleed easily, necessitating the conversion to open surgery. As of 2016, more than 9,000 cases of laparoscopic liver resection had been reported worldwide, with approximately 30% of these cases involving extensive and complex hepatectomies [2, 3]. However, the rate of conversion to open surgery in complex liver resections is almost 40% and postoperative complications are about 33.4 − 46.9% [4,5,6,7], making it difficult to fully achieve precise treatment [8]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for the development of precise planning laparoscopic surgery for special and complex hepatobiliary diseases [9].

Precise liver resection requires three-dimensional (3D) reconstruction technology, 3D printing technology, and intraoperative navigation technology [10]. Minimally invasive and precise anatomical liver resection helps the surgeon to completely remove the lesion, effectively control the bleeding, retain the maximum remaining liver function, reduce the degree of trauma, and accelerate the patient’s recovery. However, safe and effective radical liver resection requires detailed preoperative planning, simulation training, and laparoscopic navigation technology to accurately identify the appropriate surgical margins, blood vessels, and bile ducts. Preoperative planning has long relied on imaging modalities such as CT and MRI, especially 3D reconstruction imaging of liver tumors [11,12,13]. However, 3D images also have shortcomings, such as angular deviations which will make it difficult to relocate the tumor intraoperatively. These shortcomings can be reduced using 3D-printed models that visually show the range of the liver and the liver tumor accurately, and can detect the normal liver volume and residual liver volume through a computer-assisted system. Thus, 3D-printed models help surgeons to comprehensively evaluate liver function and accurately perform liver resection while reducing surgical risk [14]. Multiple studies have shown that 3D printing technology is helpful in preoperative surgical planning, promoting effective preoperative communication with patients and their families, and improving the precise surgical treatment of liver diseases [15].

The current study aims to evaluate the application value of preoperative 3D-printed dry-laboratory models in the precise planning of laparoscopic surgery for complex hepatobiliary diseases. By comparing with traditional enhanced CT or MRI, we aim to clarify the improvement effect of 3D printing models on intraoperative and postoperative complications. The successful application of this model aims to assist clinicians in decision-making, especially in helping clinicians better perform high-difficulty surgeries such as precise planning of laparoscopic surgery for complex hepatobiliary diseases, and to benefit the patients.

Patients and methods

Patients

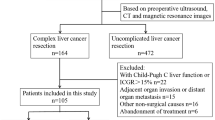

Eligible patients diagnosed with intrahepatic cholelithiasis, hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) were consecutively and prospectively enrolled between June 2018 and August 2023. The inclusion criteria were preoperative imaging revealing complex disease requiring extensive resection of liver lesions or lesions located in special sites, no distant tumor metastasis, and a liver function of Child-Pugh grade A or B. Complex hepatectomy was determined according previous studies reported [16,17,18,19], including (1) extensive left or right hemi-hepatectomy, (2) meso-hepatectomy (involving S4a and/or S8), (3) more than 3 segments, (4) special sites (S1), (5) near the first or second portal of the liver (< 1 cm). The exclusion criteria were preoperative chemoradiotherapy or severe cardiopulmonary disease. A total of 62 patients were divided into two groups: the 3D group underwent a flat layer scan of their CT or MRI [11] data, with a slice thickness of 1 mm, to generate 3D reconstructed images depicting the lesion location, critical vessels, bile ducts, and the targeted resection area. The pertinent data were then transmitted to the 3D printer in a stereolithography format, which was specifically tailored for 3D printing purposes. Using this data, a life-size 3D liver model was printed. The evaluation metrics encompassed operative duration, intraoperative bleeding and blood transfusion requirements, postoperative complications, and hospital stay duration within each group. The ethics committee of Zhejiang Provincial Peoples Hospital granted approval for the study protocol, and all participants provided informed consent to participate in the study.

The 3D Printing process

The hepatic segmentation and 3D virtual reconstruction were carried out utilizing the E3D digital medical modeling software V17.06, developed by the Central and Southern E3D Digital Medical and Virtual Reality Research Center in China [20]. This process was grounded on the patients’ CT Dicom (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) data, as depicted in Fig. 1. Subsequently, the positioning of lesions alongside intricate vascular and biliary structures was meticulously analyzed and planned using Cura 4.4.1, an open-source slicing software from Ulitmaker in the United States. This analysis culminated in the generation of G code specific to SLA (Stereo Lithography Appearance), which was recognized by the SL600 printer manufactured by ZhongRuiZhiChuang3D Technology Co., LTD. in Suzhou, China. This printer was utilized to produce physical liver models. The material used for these models comprised photosensitive resin, specifically ZR680 from ZhongRuiZhiChuang3D Technology Co., LTD. This material exhibited a bending strength of 66 ∼ 73 MPa and a fracture elongation rate of 10%∼15%. The liquid photosensitive material, after being degassed, was solidified and printed layer by layer under the control of an ultraviolet system. Notably, only the lesions along with blood vessels, bile ducts, and their branches with a diameter greater than 2 mm were printed, excluding extrahepatic parenchyma. The surface of the model was hollowed out, creating apertures with a diameter of 45–50 mm. Following curing with a UV mercury lamp and coloring in a post-processing box, the 3DP liver model was successfully completed.

Clinicopathological characteristics and Perioperative Morbidity

All the included clinicopathological characteristics were prospectively collected from the medical records system at Zhejiang Provincial Peoples Hospital, including gender, age, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, Child-Pugh, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate transaminase (AST), international normalized ratio (INR), white blood cell (WBC), C-reactive protein (CRP), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), carbohydrate antigen 19 − 9 (CA19-9), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), type of disease, disease location, proximity to the first or second hepatic portal, time of surgery, major hepatectomy, intraoperative bleeding, inoperative blood transfusion, conversed to open surgery, postoperative hospital stays, and postoperative 30-day mortality and morbidity. Comorbid illnesses were determined as consisting of obesity, diabetes mellitus, chronic cardiovascular or obstructive pulmonary disease, and renal dysfunction history. Major hepatectomy refers to the resection of more than 3 liver segments [21]. Perioperative morbidity and mortality were collected, including post hepatectomy liver failure (PHLF) [22], bleeding, blood transfusion, bile leakage, pneumonia, hydrothorax or seroperitoneum, and puncture drainage. Hospital stays were calculated from surgery to discharge. Clavien–Dindo I-II was set as minor morbidity and Clavien–Dindo III-V was set as major morbidity [23]. Comprehensive complication index (CCI) scores are obtained by entering all patients’ complications into the Clavien-Dindo system classification using the online calculator (www.cci-calculator.com).

Statistical analysis

The categorical variables were utilized to represent all the data. The Levene’s test was employed to assess the homogeneity of variance. To compare the characteristics of the two groups, the Fisher’s exact test was applied. The statistical analysis was conducted using the SPSS software, version 22.0, which was developed by SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA. Statistical significance was determined based on a two-tailed P value that was less than 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of patients

Sixty-two patients with complex hepatobiliary diseases who underwent the precise planning of LLR were included. Most of the patients were male (66%) and Child-Pugh A (90%). Among them, thirty-one patients acquired the guidance of a 3D-printed dry-laboratory model, and the others were only guided by traditional enhanced CT or MRI. There were no differences between the two groups in baseline characteristics including age, ASA score, type of disease, tumor, or disease location (all P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Intraoperative Variables and postoperative complications

Two patients suffered a conversion to open surgery in the 3D group, due to the heavy adhesion in the abdominal cavity after the first operation (Table 2). Five patients suffered a conversion to open surgery in the control group, among them, three of the patients were due to heavy intraperitoneal adhesion, one due to intraoperative bleeding, and one due to inadequate exposure of the visual field (P = 0.425). Of note, intraoperative bleeding volume in the 3D group was significantly lower than the control group (12.9 vs. 38.7, P = 0.040). No patient died within 90 days after LLR. The median score on the CCI was 20.9 (range 8.7–51.8) in the control group and 8.7 (range 8.7–43.4) in the 3D group (mean difference, -12.2, P = 0.004).The incidence of postoperative 30-day morbidity was 46.8% (3D group 29.0% vs. control group 64.5%, P = 0.010). Of these, 21.0% was minor morbidity (3D group 16.1% vs. control group 25.8%, P = 0.534) and 25.8% were major morbidity (3D group 12.9% vs. control group 38.7%, P = 0.040). Furthermore, the incidence of bile leakage in the 3D group was lower than in the control group (6.5% vs. 35.5%, P = 0.011). In addition, the median hospital stay after LLR was 9 (range 7–22) days in the 3D group, and 11 (range 10–30) days (P = 0.433).

Independent risk factors of postoperative complications

To determine the independent risk factors, variables with a univariable P < 0.1 were entered into the multivariable analyses forward stepwise (Table 3). The results of the multivariable analysis showed that precise planning LLR based on 3D-printed dry-laboratory models can reduce perioperative complications for patients with complex hepatobiliary diseases (OR 0.677, 95%CI 0.084–0.915, P = 0.035).

Subgroup Analysis

Subgroup analysis was performed according to patients with benign or malignant disease. Among the included patients, 43 (69%) patients were diagnosed with primary liver cancer (HCC, 19 patients and ICC, 24 patients), and 19 (31%) patients were diagnosed with intrahepatic cholelithiasis. For patients with liver cancer, there were no differences between the two groups in baseline characteristics (Supplement Tables 1 and 2). What’s more, 3D-printed dry-laboratory models can reduce the incidence of perioperative complications (30.0% vs. 60.9%, P = 0.042) (Table 4). For patients with intrahepatic cholelithiasis, there were also no differences between the two groups in baseline characteristics (Supplement Table 3). Of note, the results showed that 3D-printed dry-laboratory models can significantly reduce the incidence of major complications (9.1% vs. 62.5%, P = 0.041), especially the incidence of bile leakage (1 9.1% vs. 62.5%, P = 0.041) (Table 5).

Discussion

In the present study, sixty-two patients with complex hepatobiliary diseases who underwent the precise planning of LLR were included. There were no differences between the two groups in baseline characteristics. Whereas, analysis of intraoperative variables revealed that the 3D group had significantly reduced blood loss. In addition, the analysis of postoperative complications showed that the overall incidence of complications and serious complications in the 3D group was significantly reduced. Of note, precise planning LLR based on 3D-printed dry-laboratory models can reduce postoperative complications for patients with complex hepatobiliary diseases (OR 0.677, 95%CI 0.084–0.915, P = 0.035). In other words, precise planning LLR based on 3D-printed dry-laboratory models can decrease nearly 32% risk of postoperative complications. The results of the subgroup analysis further confirmed the conclusion.

It is complex and difficult to resect lesions in complex parts of the liver or lesions involving multiple liver segments [17]. Patients with such special or complex liver lesions may develop postoperative liver failure or poor prognosis due to insufficient remaining functional liver or severe complications, resulting in surgical failure. Therefore, intraoperative precise liver resection and avoidance of important vascular bile duct injury are very important [24, 25]. Currently, most evaluations of preoperative liver function and vascular location are based on imaging modalities such as CT and MRI, especially 3D reconstructed images of liver tumors. However, the lack of real contact in the 3D reconstructed images may lead to inaccurate preoperative evaluation and biased intraoperative navigation, especially in complex hepatobiliary diseases. Igami et al. suggested that there are individual differences in the 3D structure constructed based on two-dimensional images, while the spatial relationship between the tumor lesions and the surrounding tissue in the 3D-printed liver model is consistent [26]. The 3D printing technique transforms 3D reconstructed images into actual objects, enabling clinicians to directly view the complex intrahepatic blood vessels and bile ducts, improve the understanding of the complex anatomy of the liver, and improve the accuracy of liver resection [27]. The 3D-printed model can make up for the shortcomings of 3D images and enables the assessment of the normal liver volume and residual liver volume through a computer-aided system, which gives a more comprehensive assessment of liver function and contributes to the safe performance of liver surgery.

In the diagnosis and treatment of liver cancer, 3D printing technology has been used to preoperatively clarify the spatial relationship between intrahepatic vessels and tumors, which reduces the risk of intraoperative vascular injury, reduces the amount of bleeding, and shortens the operative time. Thus, 3D-printed models make up for the limitations of “spatial imagination“ [28]. As we can see from Fig. 1, the use of preoperative 3D reconstructed images may lead to liver resection errors in real-time navigation during liver resection, with the degree of error related to the experience of the surgeon. In contrast, the 3D model enables the surgeon to measure the distances between points and conduct accurate tangent positioning to obtain R0 resection. Furthermore, the surgeon can obtain the most intuitive sense of direction by continuously comparing the physical objects with the 3D model during surgery; the surgeon can adjust the spatial position of the 3D model in real-time according to the specific situation to conduct accurate intraoperative repositioning and clarify the spatial location of the lesion to achieve the effect of real-time navigation, thus reducing the surgical risk. The 3D-printed model is particularly useful for patients requiring extensive liver resection with vascular or biliary invasion. Detailed information on vascular and bile duct anatomy provided by 3D-printed models can even replace intraoperative ultrasonography or cholangiography, which is crucial in reducing the operative time and complications. Fang et al. constructed 3D visualization models of 56 patients to clearly show the anatomy of blood vessels, tumor location, and size, and the relationship between blood vessels and tumor to assist in surgical planning [29]. The 3D-printed model of eleven patients requiring complex liver resection was identical to the anatomy seen during surgery, enabling complete tumor resection. The 3D-printed model helps improve the understanding of the morphology of the lesion and the surrounding normal tissue and important structures (such as bile ducts and blood vessels) and provides intraoperative real-time navigation to enable the preservation of more normal liver tissue and reduce the occurrence of complications such as postoperative liver failure [30]. In summary, 3D-printed models reduce surgical risks, and improve the safety, effectiveness, and accuracy of surgery [1, 31].

Intrahepatic cholelithiasis is another type of liver surgery that is difficult to perform. Due to chronic inflammation, the liver atrophy, blood vessels, and bile ducts are located in a variable position. In addition, to achieve a complete cure for intrahepatic cholelithiasis, it is necessary to remove as much of the bile duct containing stones as possible, which requires preserving as much normal liver tissue as possible. In our study, subgroup analysis showed that in patients with intrahepatic cholelithiasis, the incidence of postoperative bile leakage in the 3D group was significantly lower than that in the control group. We speculate that this is because patients with intrahepatic bile duct stones often have stenosis, inflammation, local expansion, and other lesions, leading to intraoperative bile duct anatomy difficulties and possible bile leakage. We also found that the surgical plan changed in some cases after the application of the 3D-printed model in preoperative planning. One such case involved a patient with intrahepatic cholelithiasis who was scheduled to undergo laparoscopic resection of the right anterior liver lobe (segment V/VIII) based on imaging data and 3D reconstructed images. After preoperative planning with the 3D-printed model, the surgical strategy was changed to a more accurate laparoscopic resection of liver segment V, as the model showed that the anatomical resection of liver segment V was sufficient to remove the lesion while retaining the maximum amount of liver tissue.

There are also some limitations in this study. Firstly, the retrospective study had a fixed selection bias, although we used the preoperative method to reduce the impact of selection bias on outcomes. Secondly, all the LLR was performed by experienced surgeons. LLR for complex HCC requires a learning curve for surgeons. Thirdly, intrahepatic cholelithiasis, HCC, and ICC were enrolled in this study. Further validation, especially multicenter randomized controlled trials for a single disease, still needed to be conducted.

Conclusion

The 3D-printed models can help reduce postoperative complications in patients undergoing complex liver resection, especially in patients with intrahepatic cholelithiasis. Further studies are warranted to confirm the present findings.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LLR:

-

laparoscopic liver resection

- HCC:

-

hepatocellular carcinoma

- 3D:

-

three-dimensional

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

aspartate transaminase

- ALT:

-

alanine aminotransferase

- INR:

-

international normalized ratio

- WBC:

-

white blood cell

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- AFP:

-

alpha-fetoprotein

- CA19-9:

-

carbohydrate antigen 19 − 9

- CEA:

-

carcinoembryonic antigen

- HCC:

-

hepatocellular carcinoma

- ICC:

-

intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma

- UV:

-

univariable

- MV:

-

multivariable

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- OR:

-

odds ratio

- NS:

-

no significance

References

Reich H, McGlynn F, DeCaprio J, Budin R. Laparoscopic excision of benign liver lesions. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78(5 Pt 2):956–8.

Cherqui D. Evolution of laparoscopic liver resection. Br J Surg. 2016;103(11):1405–7.

Ciria R, Cherqui D, Geller DA, Briceno J, Wakabayashi G. Comparative short-term benefits of laparoscopic liver resection: 9000 cases and climbing. Ann Surg. 2016;263(4):761–77.

Zhou YM, Zhang XF, Li B, Sui CJ, Yang JM. Postoperative complications affect early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after curative resection. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:689.

Di Benedetto F, Magistri P, Di Sandro S, Sposito C, Oberkofler C, Brandon E, Samstein B, Guidetti C, Papageorgiou A, Frassoni S, et al. Safety and efficacy of robotic vs Open Liver Resection for Hepatocellular Carcinoma. JAMA Surg. 2023;158(1):46–54.

Chok KS, Ng KK, Poon RT, Lo CM, Fan ST. Impact of postoperative complications on long-term outcome of curative resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 2009;96(1):81–7.

Kusano T, Sasaki A, Kai S, Endo Y, Iwaki K, Shibata K, Ohta M, Kitano S. Predictors and prognostic significance of operative complications in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma who underwent hepatic resection. Eur J Surg Oncology: J Eur Soc Surg Oncol Br Association Surg Oncol. 2009;35(11):1179–85.

Yeow M, Soh S, Starkey G, Perini MV, Koh YX, Tan EK, Chan CY, Raj P, Goh BKP, Kabir T. A systematic review and network meta-analysis of outcomes after open, mini-laparotomy, hybrid, totally laparoscopic, and robotic living donor right hepatectomy. Surgery. 2022;172(2):741–50.

Qian NS, Liao YH, Cai SW, Raut V, Dong JH. Comprehensive application of modern technologies in precise liver resection. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2013;12(3):244–50.

Liu JP, Lerut J, Yang Z, Li ZK, Zheng SS. Three-dimensional modeling in complex liver surgery and liver transplantation. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21(4):318–24.

Wei R, Chen J, Liang B, Chen X, Men K, Dai J. Real-time 3D MRI reconstruction from cine-MRI using unsupervised network in MRI-guided radiotherapy for liver cancer. Med Phys. 2023;50(6):3584–96.

Scatton O. C Goumard 2021 Invited commentary on Balci : 3D-reconstruction and heterotopic implantation of reduced size monosegment or left lateral segment grafts in small infants: a new technique in pediatric, living-donor liver transplantation to overcome large-for-size syndrome. Surgery 170 3 986.

Pietrabissa A, Marconi S, Peri A, Pugliese L, Cavazzi E, Vinci A, Botti M, Auricchio F. From CT scanning to 3-D printing technology for the preoperative planning in laparoscopic splenectomy. Surg Endosc. 2016;30(1):366–71.

Fang CH, Tao HS, Yang J, Fang ZS, Cai W, Liu J, Fan YF. Impact of three-dimensional reconstruction technique in the operation planning of centrally located hepatocellular carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 2015;220(1):28–37.

Wang Y, Chen M, Li Y, Zhao C, Tong S, Cai Y, Wang R, Zhou T. Clinical implications of 3D printing technology in preoperative evaluation of partial nephrectomy. Zhong Nan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2022;47(3):328–33.

Luo X, Li T, Zhu JY, Huang L. [Application value of three-dimensional reconstruction in preoperative evaluation of precise hepatectomy for complex primary liver cancer]. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2021;101(28):2210–5.

Sheng W, Yuan C, Wu L, Yan J, Ge J, Lei J. Clinical application of a three-dimensional reconstruction technique for complex liver cancer resection. Surg Endosc. 2022;36(5):3246–53.

Ricker AB, Davis JM, Motz BM, Watson M, Beckman M, Driedger M, Martinie JB, Vrochides D. External validation of the Japanese difficulty score for laparoscopic hepatectomy in patients undergoing robotic-assisted hepatectomy. Surg Endosc. 2023;37(9):7288–94.

Kim J, Cho JY, Han HS, Yoon YS, Choi Y, Lee JS, Lee B, Kim J. Validation of a difficulty scoring system for laparoscopic liver resection in hepatolithiasis. Surg Endosc. 2021;35(3):1148–55.

Cheng J, Wang Z, Liu J, Dou C, Yao W, Zhang C. Value of 3D printing technology combined with indocyanine green fluorescent navigation in complex laparoscopic hepatectomy. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(8):e0272815.

Couinaud C. Liver anatomy: portal (and suprahepatic) or biliary segmentation. Dig Surg. 1999;16(6):459–67.

Balzan S, Belghiti J, Farges O, Ogata S, Sauvanet A, Delefosse D, Durand F. The 50–50 criteria on postoperative day 5: an accurate predictor of liver failure and death after hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2005;242(6):824–8. discussion 828–829.

Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240(2):205–13.

Chanwat R. Useful maneuvers for precise laparoscopic liver resection. Asian J Endosc Surg. 2018;11(2):93–103.

Gotohda N, Cherqui D, Geller DA, Abu Hilal M, Berardi G, Ciria R, Abe Y, Aoki T, Asbun HJ, Chan ACY, et al. Expert Consensus guidelines: how to safely perform minimally invasive anatomic liver resection. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2022;29(1):16–32.

Igami T, Nakamura Y, Hirose T, Ebata T, Yokoyama Y, Sugawara G, Mizuno T, Mori K, Nagino M. Application of a three-dimensional print of a liver in hepatectomy for small tumors invisible by intraoperative ultrasonography: preliminary experience. World J Surg. 2014;38(12):3163–6.

Kuroda S, Kihara T, Akita Y, Kobayashi T, Nikawa H, Ohdan H. Simulation and navigation of living donor hepatectomy using a unique three-dimensional printed liver model with soft and transparent parenchyma. Surg Today. 2020;50(3):307–13.

Takagi K, Nanashima A, Abo T, Arai J, Matsuo N, Fukuda T, Nagayasu T. Three-dimensional printing model of liver for operative simulation in perihilar cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology. 2014;61(136):2315–6.

Tomas CC, Oliveira E, Sousa D, Uba-Chupel M, Furtado G, Rocha C, Teixeira A, Ferreira P, Alves C, Gisin S et al. May : Proceedings of the 3rd IPLeiria’s International Health Congress: Leiria, Portugal. 6–7 2016. BMC Health Serv Res 2016, 16 Suppl 3(Suppl 3):200.

Silberstein JL, Maddox MM, Dorsey P, Feibus A, Thomas R, Lee BR. Physical models of renal malignancies using standard cross-sectional imaging and 3-dimensional printers: a pilot study. Urology. 2014;84(2):268–72.

Chinese S, Liver C, Clinical P, Digital I. [Clinical practice guidelines for precision diagnosis and treatment of complex liver tumor guided by three-dimensional visualization technology (version 2019)]. Nan Fang Yi Ke Da Xue Xue Bao. 2020;40(3):297–307.

Funding

This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Department of Education, General Scientific Research Projects (No.Y201840617), Zhejiang Provincial Medical and Health Science and Technology Project (No.2021KY473); the Basic Public Welfare Research Project of Zhejiang Province of China (No.LGF20H030011), and Zhejiang Medical and Health Science and Technology Plan (No.2022RC096).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Authors’ Contributions: Wei-Feng Yao, Xiao-Kun Huang, Tian-Wei Fu, and Lei Liang contributed equally to this work. Dr. Lei Liang and Dong-Sheng Huang had full access to all the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Study concept and design: Wei-Feng Yao, Lei Liang, and Dong-Sheng Huang. Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Xiao-Kun Huang, Tian-Wei Fu, Lei Jin, Cheng-Fei Du, Zhen-Yu Gao, Kai-Di Wang, Mu-Gen Dai, and Si-Yu Liu. Drafting of the manuscript: Wei-Feng Yao, Xiao-Kun Huang, Tian-Wei Fu, and Lei Jin. Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Jun-Wei Liu, and Cheng-Wu Zhang. Statistical analysis: Mu-Gen Dai, Si-Yu Liu, Jun-Wei Liu, and Cheng-Wu Zhang. Obtained funding: Wei-Feng Yao. Administrative, technical, or material support: Cheng-Wu Zhang, Lei Liang, and Dong-Sheng Huang. Study supervision: Lei Liang, and Dong-Sheng Huang.Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee of Zhejiang Provincial Peoples Hospital, and all participants provided informed consent for study inclusion.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Role of the Funder/Sponsor

The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, WF., Huang, XK., Fu, TW. et al. Precise planning based on 3D-printed dry-laboratory models can reduce perioperative complications of laparoscopic surgery for complex hepatobiliary diseases: a preoperative cohort study. BMC Surg 24, 148 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-024-02441-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-024-02441-z