Abstract

Background

With the development of minimally invasive technology, the trauma caused by surgery get smaller, At the same time, the specimen extraction surgery through the natural orifice is more favored by experts domestically and abroad, robotic surgery has further promoted the development of specimen extraction surgery through the natural orifice. The aim of current study is to compare the short-term outcomes of robotic-assisted natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSES ) and transabdominal specimen extraction(TRSE ) in median rectal cancer surgery.

Methods

From January 2020 to January 2023, 87 patients who underwent the NOSES or TRSE at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University were included in the study, 4 patients were excluded due to liver metastasis. Of these, 50 patients were in the TRSE and 33 patients in the NOSES. Short-term efficacy was compared in the two groups.

Results

The NOSES group had less operation time (P < 0.001), faster recovery of gastrointestinal function (P < 0.001), shorter abdominal incisions (P < 0.001), lower pain scores(P < 0.001). lower Inflammatory indicators of the white blood cell count and C-reactive protein content at 1, 3, and 5 days after surgery (P < 0.001, P = 0.037). There were 9 complications in the NOSES group and 11 complications in the TRSE group(P = 0.583). However, there were no wound complications in the NOSES group. The number of postoperative hospital stays seems to be same in the two groups. And there was no significant difference in postoperative anus function (P = 0.591).

Conclusions

This study shows that NOSES and TRSE can achieve similar radical treatment effects, NOSES is a feasible and safe way to take specimens for rectal cancer surgery in accordance with the indication for NOSES.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A major concern to the safety of the public’s health is the prevalence of colorectal cancer, which is the third most prevalent cancer and has a very high fatality rate [1, 2]. There are multiple treatments for rectal cancer, and surgery remains one of the most important ways. Laparoscopic surgery as a minimally invasive technique for the treatment of colorectal has been confirmed by many studies to ensure its safety and reliability [3, 4]. Laparoscopic surgery has also been widely used in clinical [5, 6]. So far, NOSES, as an emerging minimally invasive technology, has caused heated discussions in the minimally invasive surgical community [7,8,9], especially in rectal surgery [10,11,12], the emergence of NOSES, which solves the problems caused by incisions in traditional surgery, improves the mental health of patients, and has good short-term efficacy [13]. In recent years, the popularity of robotic colorectal cancer surgery has been rising, and the concepts of radical treatment, precision, and minimally invasive have been continuously refined, and NOSES surgery, as an emerging minimally invasive technology, has further reduced the impact of surgical trauma on the body, eliminated abdominal scar incision, and avoided complications related to abdominal wall incision, and has been widely used and carried out [14]. In addition to the benefits of patients, the high-definition lens of the robotic surgery system and the flexible robotic arm greatly remove the trembling of the operator’s hand, improve the flexibility and accuracy of the operator’s operation, and are more conducive to challenging operations in narrow spaces. Compared with laparoscopy, the robotic surgical system has great advantages in some aspects, such as postoperative patient urination function, sexual function, surgical complications [12, 15, 16]. Robotic surgical systems, combined with NOSES, may bring greater benefits to patients. Therefore, we reviewed the clinical data of 87 patients who underwent robot-assisted radical rectal resection from January 2020 to January 2023, who underwent conventional abdominal specimen extraction and radical rectal cancer resection through natural orifice. Then the short-term efficacy of different specimen retrieval routes is compared to explore the safety and feasibility of NOSES in robotic radical rectal cancer surgery.

Methods

In the current study, we collected the clinicopathological data of median rectal cancer surgery patients who underwent robotic surgery at the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University between January 2020 and January 2023. Then analyzed. A total of 87 patients with median rectal cancer underwent robotic surgery, 4 patients were excluded due to liver metastasis, and a total of 83 patients met the criteria, including 33 cases in the noses group and 50 cases in the abdominal specimen group. The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. The study compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consents were obtained from all of the patients.

Inclusion Criteria: (1) age greater than 18 years and below 80 years old; (2) Endoscopic biopsy confirmed primary colon adenocarcinoma; (3) According to the preoperative examination and intraoperative observation, it was confirmed that there was no distant metastasis; (4) American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score I, II, or III; (5) Sign informed consent. (6) According to imaging examination, colonoscopy, intraoperative and postoperative pathology, it was confirmed that the tumor was located in the middle rectum;

Exclusion criteria: (1) concurrent with other malignant tumors; (2) Cases of emergency surgery due to bleeding, obstruction, and perforation; (3) Transit laparotomy; (4) Incomplete data or missing follow-up data; (5) Patients with preventive stoma or patients with ostomy for other reasons.

Surgical procedures

The patients’ position and trocar position can be referred to our previous study [17]. After successful anesthesia, abdominal exploration is performed to determine whether there are metastases and other conditions, and digital rectal examination is combined with palpation of abdomen to determine the location and size of the tumor. Expose the inferior mesenteric artery, clean the lymph nodes at the root of the vessel, ligate and separate the inferior mesenteric artery, free sigmoid colon and rectum, free the entire mesentery, bare the rectum, cut the closure 2 cm from the lower edge of the tumor to break the rectum. We will pull the severed intestinal tube towards the anus to determine if its length is sufficient. If the intestinal tube is not long enough, we will free the spleen and colon. Fully and softly extend the anus, and rinse the rectal lumen with iodophors through the anus. A protective sleeve is inserted through the helper hole, and the protective sleeve is dragged out of the anus through the rectum, and the proximal rectum is dragged out through the protective sleeve, and the terminal ileum is cut 10 cm above the tumor. The anvil is placed into the sigmoid colon stump, clamped with toothed forceps, and sent to the abdominal cavity through the protective sleeve. Finally, the stapler is inserted through the anus, then complete the end anastomosis, and the iodophors injection test checks whether there is leakage in the anastomosis and sutures the anastomosis. The part of the surgical process of NOSES were shown in the Fig. 1.

Key surgical steps of NOSES (A–F). (A) Expose the inferior mesenteric artery. (B) Ligate the inferior mesenteric artery. (C) A sterile protective sleeve was placed into the anus to establish sterile access. (D, E) The proximal rectum is dragged out through the protective sleeve. (F) Suturing the anastomosis

Parameters of observation and evaluation parameters

The general demographic data of the patient are as follows: age, sex, body mass index (BMI). The surgical parameters of the patients were as follows: American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, total time to surgery, intraoperative blood loss, white blood cell count, and C-reactive protein (CRP) were used to assess the postoperative inflammatory response, postoperative activity time, postoperative ventilation time, and postoperative complications were recorded by Clavien-Dindo classification, Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) scores, the Wexner Incontinence Score assesses function 3 months after surgery, postoperative hospital stay.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses used SPSS26.0 and were tested for normality for all parameters, with measurements that conforming to the normal distribution expressed as mean ± SD and non-normally distributed data expressed as median and range, using either the independent sample t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test, respectively. Counting data is expressed as frequency and percentage, using the χ2 test or the Fisher exact probability method. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Clinical baseline characteristics

Table 1 shows that the sex, age, BMI, preoperative white blood cell count, preoperative C-reactive protein level, tumor distance from the anus, tumor size, TNM stage, and ASA score were compared in the study, then there was no significant difference in clinical baseline characteristics between the two groups (p > 0.05).

Comparison of perioperative indexes between TRSE group and NOSES group

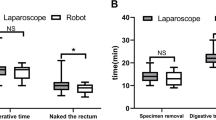

These table presents comparison of the perioperative data of the two groups, the operation time of the two groups was slightly different (143.33 ± 30.71 min in the NOSES group vs. 166.50 ± 30.28 min in the TRSE group P = 0.001), and the intraoperative blood loss was similar (133.80 ± 62.33 ml in the TRSE group VS 106.67 ± 61.93ml in the NOSES group, P = 0.06). But the gastrointestinal recovery function in the NOSES group was better than that in the TRSE group (66.70 ± 6.69 h in the TRSE group VS 58.48 ± 4.56 h in the NOSES group, P < 0.01), and the length of abdominal incision was significantly shorter than that in the TRSE group (11.9 ± 0.6 cm in the TRSE group vs. 4.9 ± 0.2 cm in the NOSES group, P < 0.001). In terms of postoperative recovery indicators, the number of days of postoperative hospital stay was the same in the TRSE group and the NOSES group (P = 0.470 (Table 2). However, pain scores in the NOSES group were better than in the RARS group (P < 0.001), and significantly fewer patients required additional analgesics than in the TRSE group. In terms of surgical stress, we compared the white blood cell count and C-reactive protein content of the two groups at 1, 3 and 5 days after surgery, and the inflammatory indicators of the NOSES group were lower than those in the TRSE group (P = 0.005, P = 0.002) (Table 3; Fig. 2 ). In terms of postoperative complications, there were 9 complications in the NOSES group and 11complications in the TRSE group. It is worth mentioning that there were no complications in the wounds of the NOSES group. And there was no significant difference in postoperative anus function (P < 0.001, Table 4). No bacteria were cultured in the peritoneal lavage fluid of both NOSES and TRSE groups of patients.

Discussion

With the continuous development of minimally invasive technology, radical rectal cancer surgery has coexisted from traditional laparotomy to laparoscopic surgery [18, 19], and now robotic surgery [20]. In recent years, the number of reports of colorectal cancer resection of robotic natural orifice specimen extraction has increased [21]. At the same time, there is a variation of NOSES [9]. The surgical treatment of colorectal cancer is gradually developing in the direction of minimally invasive surgery, which is the current trend in the field of surgery. Conventional laparoscopic rectal cancer surgery involves removing the tumor specimen through an incision of 5 to 7 cm in the abdomen [22, 23]. With the development of surgical technology and the deepening of minimally invasive concepts, a new surgical technology (NOSES) to avoid abdominal auxiliary incision. To take specimens through the natural orifice has gradually become a research hotspot [24]. The safety and postoperative effect of surgery are topics of great concern [25,26,27],what’s more, the safety of surgery is a prerequisite for a new technology operation. In this study, the NOSES group was performed by the same surgeon to avoid the drift of the study data caused by the learning curve [28], and the surgeon had rich surgical experience. The procedure strictly adheres to the principle of aseptic surgery, uses a sterile protective sleeve to remove the specimen, then sterilizes it in time, finally rinses the abdominal cavity with plenty of normal saline. In addition, the results of this study showed that the bacterial culture of postoperative abdominal pelvic lavage fluid in the NOSES group was negative. In terms of postoperative complications, there was no significant difference in postoperative intraoperative infection between the NOSES group and the abdomen group. In addition, the average operation time of the two groups was slightly different, and the author considered that the time for gastrointestinal reconstruction was shortened and the amount of bleeding was similar. In terms of the tumor-free principle, we found no significant difference in the number of lymph node dissections between the two groups. This is due to the robotic surgical system’s wider field of view and flexible robotic arms. These results further confirm that robotic colorectal cancer resection through natural orifice specimens has a surgical efficacy that is not inferior to robotic-assisted rectal cancer resection [29, 30]. The short-term efficacy of surgery is an important indicator to evaluate the quality of robotic NOSES surgery for colorectal cancer. Because the length of the abdominal wall incision in the robotic NOSES surgery is significantly shorter than the abdomen group, the damage to the abdominal wall is reduced, the postoperative pain of the patient is also significantly reduced, the additional analgesic required is also less, at the same time the patient can get out of bed early. Therefore, the recovery time of gastrointestinal function in the NOSES group is earlier than the abdomen group. NOSES surgery has no incision in the abdomen, doesn’t destroy the integrity of the abdominal wall and avoid the occurrence of near and long incision dehiscence and incision hernia; Similarly, we compared leukocyte markers and C-reactive protein levels at 1, 3, and 5 days after surgery between the two groups. A research indicated [31]that the stress response to surgery may promote the growth of pre-existing micrometastasis or may trigger tumor spread. The inflammatory indexes of the NOSES group were lower than those in the abdomen group, which indicated that the NOSES group had less interference with the patient’s body and a more obvious advantage of minimally invasive surgery. Of course, there are some limitations to this study. First, it was retrospective research, it has the unavoidable selective bias. Secondly, because it is a single-center study, it is limited by its small size and has insufficient sample size. In order to reduce differences in background or surgical skills between different surgeons, it can ensure that all surgeries in this study were performed by a team of professionals led by the same surgeon. To this end, the center is carrying out a multicenter prospective randomized controlled study of robotic NOSES, which is believed to provide a higher level of evidence for robotic NOSES, so as to better guide the surgical treatment of colorectal cancer. In addition, the postoperative follow-up time in this study was short, and the long-term survival outcomes and disease-free survival of the two groups were not studied.

Conclusions

Robotic NOSES surgery for colorectal cancer is a safe and feasible minimally invasive technique, and has a shorter abdominal incision, less pain, less surgical stress, faster postoperative motion, more conducive to the recovery of intestinal function. For suitable colorectal cancer patients, this technology can be further promoted. Of course, NOSES surgery is still developing, and the author also hopes that surgical experts across the country and even the world can strictly follow the guidelines to perform noses surgery for suitable patients and obtain greater benefits for patients.

Data availability

Access to the database can be obtained from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- NOSES:

-

natural orifice specimen extraction surgery

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- TNM:

-

tumor-node-metastasis

- TRSE:

-

transabdominal specimen extraction

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71(3):209–49.

Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal Cancer: a review. JAMA. 2021;325(7):669–85.

Keller DS, Berho M, Perez RO, Wexner SD, Chand M. The multidisciplinary management of rectal cancer. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17(7):414–29.

Toiyama Y, Kusunoki M. Changes in surgical therapies for rectal cancer over the past 100 years: a review. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2020;4(4):331–42.

Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Quirke P, Copeland J, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(21):3061–8.

Miskovic D, Foster J, Agha A, Delaney CP, Francis N, Hasegawa H, Karachun A, Kim SH, Law WL, Marks J, et al. Standardization of laparoscopic total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer: a structured international expert consensus. Ann Surg. 2015;261(4):716–22.

Garcia LE, Taylor J, Atallah C. Update on minimally invasive Surgical Approaches for rectal Cancer. Curr Oncol Rep. 2021;23(10):117.

Rutgers ML, Detering R, Roodbeen SX, Crolla RM, Dekker JWT, Tuynman JB, Sietses C, Bemelman WA, Tanis PJ, Hompes R. Influence of minimally invasive resection technique on Sphincter Preservation and short-term outcome in low rectal Cancer in the Netherlands. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64(12):1488–500.

Efetov SK, Tulina IA, Kim VD, Kitsenko Y, Picciariello A, Tsarkov PV. Natural orifice specimen extraction (NOSE) surgery with rectal eversion and total extra-abdominal resection. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23(9):899–902.

Salibasic M, Pusina S, Bicakcic E, Pasic A, Gavric I, Kulovic E, Rovcanin A, Beslija S. Colorectal Cancer Surgical Treatment, our experience. Med Arch. 2019;73(6):412–4.

Feng Q, Yuan W, Li T, Tang B, Jia B, Zhou Y, Zhang W, Zhao R, Zhang C, Cheng L, et al. Robotic versus laparoscopic surgery for middle and low rectal cancer (REAL): short-term outcomes of a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;7(11):991–1004.

Thakkar S, Pancholi A, Carleton N. Natural orifice specimen extraction for colorectal cancer removal: the best of both worlds. Gastrointest Endosc. 2021;94(3):651–2.

Gorgun E, Cengiz TB, Ozgur I, Dionigi B, Kalady MF, Steele SR. Outcomes and cost analysis of robotic Versus Laparoscopic Abdominoperineal Resection for rectal Cancer: a case-matched study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2022;65(10):1279–86.

Lirici MM, Hüscher CG. Techniques and technology evolution of rectal cancer surgery: a history of more than a hundred years. Minim Invasive Ther Allied Technol. 2016;25(5):226–33.

Wolthuis AM, Meuleman C, Tomassetti C, D’Hooghe T, Fieuws S. De Buck van Overstraeten A, D’Hoore A: how do patients score cosmesis after laparoscopic natural orifice specimen extraction colectomy? Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(6):536–41.

Lurje G, Raptis DA, Steinemann DC, Amygdalos I, Kambakamba P, Petrowsky H, Lesurtel M, Zehnder A, Wyss R, Clavien PA, et al. Cosmesis and body image in patients undergoing single-port Versus Conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a Multicenter double-blinded Randomized Controlled Trial (SPOCC-trial). Ann Surg. 2015;262(5):728–34. discussion 734 – 725.

Ye SP, Zhu WQ, Liu DN, Lei X, Jiang QG, Hu HM, Tang B, He PH, Gao GM, Tang HC, et al. Robotic- vs laparoscopic-assisted proctectomy for locally advanced rectal cancer based on propensity score matching: short-term outcomes at a colorectal center in China. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2020;12(4):424–34.

Jacobs M, Verdeja JC, Goldstein HS. Minimally invasive colon resection (laparoscopic colectomy). Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1991;1(3):144–50.

Schwenk W, Haase O, Neudecker J, Müller JM. Short term benefits for laparoscopic colorectal resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;2005(3). Cd003145.

Cheng CL, Rezac C. The role of robotics in colorectal surgery. BMJ. 2018;360:j5304.

Li L, Liu K, Li T, Zhou J, Xu S, Yu N, Guo Z, Yao H. Robotic natural orifice specimen extraction surgery versus conventional robotic resection for patients with colorectal neoplasms. Front Oncol. 2023;13:1153751.

Leung KL, Lai PB, Ho RL, Meng WC, Yiu RY, Lee JF, Lau WY. Systemic cytokine response after laparoscopic-assisted resection of rectosigmoid carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 2000;231(4):506–11.

Bisgaard T, Klarskov B, Rosenberg J, Kehlet H. Characteristics and prediction of early pain after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Pain. 2001;90(3):261–9.

Peters MJ, Mukhtar A, Yunus RM, Khan S, Pappalardo J, Memon B, Memon MA. Meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials comparing open and laparoscopic anti-reflux surgery. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104(6):1548–61. quiz 1547, 1562.

Zhou JJ, Li TG, Lei SL, Chen WD, Liu KJ, Liu B, Yao HL. [Analysis of robotic natural orifice specimen extraction surgery on 162 cases with rectal neoplasms]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020;23(4):384–9.

Houqiong J, Ziwen W, Chonghan Z, Penghui H, Hongxin Y, Weijie L, Dongning L, Taiyuan L. Comparison of transabdominal wall specimen retrieval and natural orifice specimen extraction robotic surgery in the outcome of colorectal cancer treatment. Front Surg. 2023;10:1092128.

Liu L, Chiu PW, Reddy N, Ho KY, Kitano S, Seo DW, Tajiri H. Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) for clinical management of intra-abdominal diseases. Dig Endosc. 2013;25(6):565–77.

Zorron R, Maggioni LC, Pombo L, Oliveira AL, Carvalho GL, Filgueiras M. NOTES transvaginal cholecystectomy: preliminary clinical application. Surg Endosc. 2008;22(2):542–7.

Brincat SD, Lauri J, Cini C. Natural orifice versus transabdominal specimen extraction in laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: meta-analysis. BJS Open 2022, 6(3).

Ding Y, Li Z, Gao H, Cao Y, Jin W. Comparison of efficacy between natural orifice specimen extraction without abdominal incision and conventional laparoscopic surgery in the treatment of sigmoid colon cancer and upper rectal cancer. J buon. 2019;24(5):1817–23.

Behrenbruch C, Shembrey C, Paquet-Fifield S, Molck C, Cho HJ, Michael M, Thomson BNJ, Heriot AG, Hollande F. Surgical stress response and promotion of metastasis in colorectal cancer: a complex and heterogeneous process. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2018;35(4):333–45.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

Science and technology plan project of Jiangxi Provincial Health Commission (No. 202310016). Key Research Project in Jiangxi Province, 20202BBG73032.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SPY and TYL designed the study; TYL performed surgical operations; DNL and WJL collected data; SPY and CW analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript; SPY and HCX proofread and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review board of The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University. The study compliance with the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consents were obtained from all of the patients.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ye, Sp., Lu, Wj., Liu, Dn. et al. Comparison of short-term efficacy analysis of medium-rectal cancer surgery with robotic natural orifice specimen extraction and robotic transabdominal specimen extraction. BMC Surg 23, 336 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-02216-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-023-02216-y