Abstract

Background

Transvaginal intestinal evisceration is an extremely rare surgical emergency with potentially fatal consequences. Only a few more than 100 cases with this pathology have been described in the literature. Aetiology is also unclear and multifactoral.

Case presentation

We report the case of an 80-year-old female who presented with sudden severe abdominal pain and spontaneous small bowel evisceration through the vagina along with associated high-grade uterine prolapse. The loops and their mesentery appeared edematous, thickened and dusky, but without apparent necrosis. An urgent laparotomy was performed with subsequent reduction of the prolapsed small bowel into the abdomen, hysterectomy, partial resection of the vagina and vaginal closure. Additional cholecystectomy was necessary because of the visible pathologic changes of the gallbladder. The postoperative period was uneventful. The unique feature of our case is that there was no trigger factor (trauma, constipation or a coughing episode that would increase the intra-abdominal pressure), provoking the vaginal rupture and intestinal evisceration through it in the context of pelvic floor weakness.

Conclusions

Early detection and surgical management are crucial for preventing bowel ischemia and abdominal sepsis. If the eviscerated intestine is ischaemic and non-viable, this requires resection and anastomosis. The approach should be individualized and performed by a multidisciplinary team.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Transvaginal intestinal evisceration is a rare surgical emergency with potentially fatal consequences [1,2,3,4,5,6]. A limited number of cases has been published in the literature, so the exact incidence is difficult to determine [7, 8]. Aetiology is also unclear and multifactoral [7, 8]. The usual clinical presentation includes small bowel obstruction due to a herniation of the intestines through the vagina. Diagnosis is made on the imaging tests or during laparotomy [4, 9]. Very rarely, it could present dramatically with large loops of small bowel prolapsing through the vagina resulting in a significant risk of loss of bowel viability. [4, 10]

Our patient presented with sudden severe abdominal pain and spontaneous small bowel evisceration through the vagina along with associated uterine prolapse requiring emergent surgical intervention. This case report is compliant with the CARE Guidelines [11].

Case presentation

An 80-year-old female living independently presented with sudden severe abdominal pain, weakness, and dizziness. The patient reported she had no constipation or a coughing episode that would increase the intra-abdominal pressure. She did not experience any recent trauma. The patient’s obstetric history included one full-term vaginal delivery and long-standing presence of uterine prolapse (grade 3) treated with pessary placement. However, she stopped using it 2 years ago. Other concomitant diseases were arterial hypertension and anxiety disorder managed with Diazepam. After examination by a gynaecologist, the patient was referred to our department because of established an irreducible small-bowel prolapse through the vagina and suspected changes of the intestinal vitality.

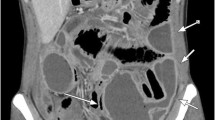

The physical examination revealed impaired general condition, pale skin, a pulse rate of 90 per minute, and blood pressure of 109/60. The patient’s position in the bed was passive. The abdomen was significantly tender in the lower quadrants with hypoactive bowel sounds. Perineal examination showed 40–50 cm of small bowel prolapsing through the vagina along with associated high-grade uterine prolapse. The loops appeared edematous and thickened, with changed colour, but without obvious necrosis. The mesentery was dusky red and ecchymotic with signs of impaired venous return (Figs. 1 and 2). Routine laboratory tests revealed anaemia (haemoglobin 91 g/l), increased values of leukocytes (12.3 × 109 cells/l), CRP (68 mg/dL), and fibrinogen (6.4 g/l). Blood gas analysis showed decompensated metabolic acidosis (pH 7.24, BE – 9.7, satO2 79%, tCO2 16.5). Fluid resuscitation and intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotic administration (Metronidazole and Cefoperazon) were timely initiated.

Because the intraperitoneal reposition of the eviscerated intestine was not possible and the diagnosis was visible from the examination, CT was not performed to save time. The decision for an early as possible operation was taken into account the status of the prolapsing intestine, and the goal was the preservation of intestinal vitality and avoidance of intestinal resection, if feasible.

The eviscerated intestine was wrapped with warm, sterile, saline-soaked packs. The surgical procedure started with a lower midline incision which later was extended proximally. After assessing the damage, the prolapsed small bowel was reduced into the abdomen. The exploration revealed a laceration of the peritoneum of the Douglas cavity and a defect in the posterior vaginal fornix. The vagina was distended and thickened in its upper third, probably due to the long-term uterine prolapse and pessary use. The affected intestinal loop was localized 30 cm proximally to the ileocecal valve. After the reposition, the small bowel loop restored its vital colour, so bowel resection was not required. Several small mesenteric tears were found and sutured subsequently. The uterus was enlarged due to the presence of several fibroids, and the uterine round ligaments were highly distended. There were no visible signs of malignancies. Intraoperative consultation with a gynaecologist was made because of the changes in the uterus and upper part of the vagina. A hysterectomy with resection of the upper third of the vagina was performed. Vaginal closure, plication of the uterine round ligaments, and fixation to the vaginal cuff were carried out. The peritoneum from the lateral pelvic sidewalls was mobilized, and the repair was performed. Subsequently, the peritoneal cavity was washed with saline. The additional pathological finding was the highly enlarged gallbladder with thickened walls and multiple gallstones inside. So, cholecystectomy was performed. Three drains were inserted—one was placed in the subhepatic space, one over the restored peritoneum of the pelvis, and the last was extraperitoneal, near the vaginal cuff. The same antibiotic regimen initiated prior to surgery was undertaken postoperatively. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the 11th postoperative day. Two years later, the patient has no complaints related to the surgery.

Discussion

Hypernaux et al. described the transvaginal prolapse of abdominal content for the first time in 1864 [12]. Later in 1907, McGregor reported protrusion of small bowel through vaginal wall rupture [13]. Since then, a few more than 100 cases with this pathology have been reported in the literature [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10, 14]. About 70% of the affected patients are postmenopausal women [3, 6]. This increased incidence could be explained by vaginal wall atrophy, which coincided with the triad of hypoestrogenism, chronic tissue devascularization, and pelvic floor weakness [10, 15]. Most patients with transvaginal evisceration have previous gynaecological surgery or concomitant pelvic organ prolapse [10, 15, 16]. According to a review of all hysterectomies and pelvic repairs performed at Mayo Clinic from 1970 through 2001, Croak et al. reported a 0.032% incidence of vaginal evisceration after a pelvic operation [10]. Somkuti et al. described ten risk factors for apical vaginal rupture after an abdominal or vaginal hysterectomy: (1) poor technique, (2) postoperative infection, (3) hematoma, (4) coitus before healing, (5) age, (6) radiotherapy, (7) corticosteroid therapy, (8) trauma or rape, (9) the previous vaginoplasty, and (10) use of the Valsalva manoeuvre [17]. Many other factors can influence this condition, such as lifestyle, hypothyroidism, obesity, multiparous women, previous pelvic radiotherapy, and poor collagen structure [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. However, most case reports on the topic described a trigger moment for the evisceration as recent trauma or surgery, coughing, constipation or any other factor that would increase the intra-abdominal pressure suddenly in the context of pelvic floor weakness [8, 16, 18, 19]. In premenopausal women, transvaginal intestinal evisceration is extremely rare and often associated with instrumentation, obstetric injury or coital trauma, which vaginal lacerations may accompany [7, 10, 14, 20]. Our patient was a postmenopausal woman with concomitant uterine prolapse, which may have weakened the vaginal wall. However, the unique feature of the case is that there was no event provoking the vaginal rupture and intestinal evisceration through it.

Transvaginal small bowel evisceration is related to 6–8% mortality and a high morbidity rate (15–20%) [1, 3, 4, 21]. Complications associated with this condition include intestinal ischaemia and gangrene, abdominal sepsis and deep vein thrombosis [1, 2, 22]. Because of that, early recognition and surgical treatment are crucial. Due to the rarity of this condition, there is no unified consensus about the optimal surgical technique [23]. So, the surgical approach should be individualized and performed by a multidisciplinary team. Guttman and Afilalo emphasized five key points that may aid in the acute management of rupture and evisceration: (1) stabilizing the patient; (2) managing the patient’s fluid status, especially in patients with shock; (3) preserving the bowel in a moist saline wrap; (4) administering broadspectrum antibiotics to cover gastrointestinal flora, and (5) initiating the immediate surgical repair [10]. The transvaginal intestinal evisceration management must start with a detailed assessment of the herniated viscus. A reduction may be attempted if the eviscerated bowel is viable, has not been previously irradiated, and there are no signs of an acute abdomen. Subsequent transvaginal surgical repair may be feasible [3, 4]. This, however, limits thorough inspection of the bowel length [19]. So, in these cases, a combined laparoscopic and vaginal approach may be beneficial to enable appropriate inspection of the abdominopelvic viscera before repairing the vaginal defect [8, 19]. However, in most cases such as ours, the intraperitoneal reposition of the eviscerated intestine was not possible (due to the status of the affected loops or the vaginal defect is located too high) [19]. So, this required laparotomy combined with a transabdominal or transvaginal vault repair [3, 4, 10, 19]. Ischaemic, non-viable bowel would require resection and anastomosis [3,4,5, 7, 10]. In our case, after transabdominal reduction, eviscerated small intestine restored its vital colour and hysterectomy, partial resection of the vagina and vaginal closure was performed due to high-grade uterine prolapse. Additional cholecystectomy was necessary because of the visible pathologic changes of the gallbladder.

Conclusions

Transvaginal intestinal evisceration is an extremely rare emergency. Early detection and surgical management are crucial for preventing bowel ischemia and abdominal sepsis. If the eviscerated intestine is ischaemic and non-viable, this requires resection and anastomosis. The approach should be individualized and performed by a multidisciplinary team.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets supporting the conclusions of this article are included in the report.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- satO2 :

-

Oxygen saturation

- BE:

-

Base excess

- tCO2 :

-

Total carbon dioxide

- cm:

-

Centimetres

References

Rogers P, Lee H, Jape K, Ng ZQ, Koong D. Vaginal evisceration of small bowel. J Surg Case Rep. 2019;11:1–3.

Amakpa E, Hernandez-Gonzalez G, Camejo-Rodriguez E. Small bowel evisceration in a perforated uterine prolapse. Ghana Med J. 2021;55(2):156–9.

Rana AM, Rana A, Salama Y. Small bowel evisceration through the vaginal vault: a rare surgical emergency. Cureus. 2019;11(10): e5947.

Bendjaballah A, Taieb M, Haidar A, Khiali R, Ammari S, et al. Evisceration of small intestine through the vagina: a rare surgical cause of acute intestinal obstruction. J Univer Surg. 2020;8(3):1.

Negrete JR, Molina GA, Sanchez AC, et al. Transvaginal evisceration of the small bowel a rare and potentially lethal event, a case report. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;65: 102352.

Toh JWT, Lee T, Chiong C, Ctercteko G, Pathma-Nathan N, El Khoury T, Wright D, King J. Transvaginal evisceration of small bowel. ANZ J Surg. 2018;89(6):774–6.

Parra RS, Rocha JJ, Feres O. Spontaneous transvaginal small bowel evisceration: a case report. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2010;65:559–61.

Chan A, Oluwajobi O, Ehsan A, et al. Transvaginal evisceration of the small bowel more than 15 years after abdominal hysterectomy and vaginal surgery. Cureus. 2021;13(3): e13955.

Kang WD, Kim SM, Choi HO. Vaginal evisceration after radical hysterectomy and adjuvant radiation. J Gynecol Oncol. 2009;20:63–4.

Croak AJ, Gebhart JB, Klingele CJ, Schroeder G, Lee RA, Podratz KC. Characteristics of patients with vaginal rupture and evisceration. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:572–6.

Agha RA, Borrelli MR, Farwana R, Koshy K, Fowler A, Orgill DP, For the SCARE Group. The SCARE 2018 statement: updating consensus Surgical CAse REport (SCARE) Guidelines. Int J Surg. 2018;60:132–6.

Hyernaux M. Rupture tramatique du vagin; issue des intestines a l’extieur; application du grand forceps au detroit superieur; gurison. Bull Mem Acad Med Belg. 1864;2:957.

McGregor AN. Rupture of the vaginal wall with protrusion of small intestine in woman of 63 years of age. Br J Gynecol. 2005;11:252–8.

Nasr AO, Tormey S, Aziz MA, Lane B. Vaginal herniation: case report and review of the literature. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(1):95–7.

Kowalski LD, Seski JC, Timmins PF, Kanbour AI, Kunschner AJ, Kanbour-Shakir A. Vaginal evisceration: presentation and management in postmenopausal women. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;183:225–9.

Mcmaster BC, Molins C. Small bowel evisceration after spontaneous vaginal cuff rupture. Cureus. 2019;11(8): e5535.

Somkuti SG, Vieta PA, Daughtery JF, Hartley LW, Blackmon EB Jr. Transvaginal evisceration after hysterectomy in premenopausal women: a presentation of three cases. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:567–8.

Morgan D, Kamdar N, Swenson C, Kobernik E, Sammarco A, Nallamothu B. Nationwide trends in the utilization of and payments for hysterectomy in the United States among commercially insured women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;218:425.e1-425.e18.

Gheewala U, Agrawal A, Shukla R, Bhatt R, Srivastava S. Transvaginal small bowel evisceration in known case of uterine prolapse due to trauma. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(1):PD09–PD10.

Moen MD, Desai M, Sulkowski R. Vaginal evisceration managed by transvaginal bowel resection and vaginal repair. Int Urogynecol J. 2003;14:218–20.

O’Brien LM, Bellin LS, Isenberg GA, Goldstein SD. Spontaneous transvaginal small-bowel evisceration after perineal proctectomy: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:698–9.

Doshani A, Teo REC, Mayne CJ, Tincello DG. Uterine prolapse. BMJ. 2007;335(7624):819–23.

Hassan W, Narasimhan V, Arachchi A, Manolitsas T, Teoh W. Small bowel evisceration from vagina. J Surg Case Rep. 2021;8:rjab343.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the patient’s approval to present this case and acknowledge all the medical and surgical staff who cared for the patient.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EA wrote the paper. DB collected the literature for the review in the report. Sasho Bonev, EA, and ZS performed the surgery described in this report. AY revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and technical details. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval from the hospital is not applicable for the Case report. The patient’s approval has been given to publish this case report, including the images.

Consent for publication

Written consent for publication of this case report, including the images, was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Arabadzhieva, E., Bulanov, D., Shavalov, Z. et al. Spontaneous transvaginal intestinal evisceration in case of long-standing uterine prolapse. BMC Surg 22, 157 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-022-01615-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-022-01615-x