Abstract

Background

A floating thrombus in an ascending aorta with normal morphology is very rare, but when it does occur, it may induce a systemic embolism or fatal stroke. The pathophysiological mechanisms of aortic mural thrombi remain unclear, and there is no consensus regarding therapeutic recommendations.

Case presentation

We report a 49-year-old male who presented with chest discomfort for 5 days and was admitted to our emergency unit. A contrast-enhanced computed tomography angiography (CTA) surprisingly demonstrated a large filling defect suggestive of a thrombus in his otherwise healthy distal ascending aorta. Surgical resection of the mass and attachment site was performed. Histological examination confirmed that the mass was a thrombus, but the cause of the thrombus formation was unknown.

Conclusions

floating aortic thrombi are rare, and they are prone to break off, thus carrying a potential risk for embolic events with catastrophic consequences. Surgical resection, both of the aortic thrombus and attachment site, as well as postoperative anticoagulant administration, are standard treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

An aortic mural thrombus (AMT) without an aneurysm or dissection is rare, with an incidence rate of about 0.45% [1]. It is occasionally identified incidentally, either by a source of systemic emboli or by computed tomography angiography (CTA). The most common locations for AMTs are the aortic isthmus, descending thoracic aorta and lower abdominal aorta, with the rarest location being the ascending aorta [2,3,4]. The pathogenesis and treatment strategies for AMTs are still limited to those found in case reports, and there is no consensus. We report on a 49-year-old male who presented with chest discomfort for 5 days and was admitted to our emergency unit. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography angiography (CTA) showed the presence of an ascending aorta active occupancy, which was successfully resected surgically. Histological examination of the mass confirmed that it was a thrombus.

Case presentation

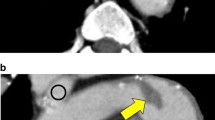

A 49-year-old man presented with chest discomfort for 5 days and was admitted to our emergency unit. His medical history was unremarkable, except for cigarette smoking and a lower left limb embolic event that was treated by surgical embolectomy 3 years prior. Electrocardiography and laboratory tests were normal. A contrast-enhanced CTA surprisingly demonstrated a large filling defect suggestive of a thrombus in a healthy distal ascending aorta (Fig. 1, Additional file 1: Video 1). Further investigations, including autoimmune, thrombophilia, and blood culture studies were negative (Table 1), and so did his family.

For a young male with such a large floating thrombus in the ascending aorta, we chose surgical removal of the intra-luminal mass to avoid the recurrence of a peripheral or visceral embolism. After a discussion with professionals from multiple disciplines, we performed surgical intervention for this patient. Under general anesthesia, a preoperative transesophageal echocardiography showed a mobile lesion on the anterior wall of the distal ascending aorta (Additional file 2: Video 2). The surgery was performed through a standard median sternotomy on cardiopulmonary bypass after heparinized. The right femoral artery and the superior and inferior vena cavae were cannulated, with the intent of obtaining deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (at 24 ℃). The heart was arrested with retrograde cardioplegia, followed by retrograde cerebral perfusion and circulatory arrest. A transverse aortotomy was performed, and the ascending aorta and arch were carefully inspected. A 5.5 × 3.0 cm mixed thrombus was attached to the aortic wall at the junction of the ascending aorta and proximal arch (Fig. 2). After thrombus removal, an extensive area of intimal defect and an abnormally thick and fragile aortic wall was observed at the attachment site. To seal the prothrombotic area and avoid recurrence, the ascending aorta and proximal arch were replaced with a 28 mm Dacron vascular prosthesis conduit (Gelweave, Vascutek, Terumo, Inchinnan, UK). Histological examination of the aortic specimen confirmed the thrombotic nature of the structure, and no sign of connective tissue disorders or malignancy was detected. The postoperative course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged from the hospital 7 days after surgery. No complications were reported in 3-month follow-up. As we resected the aortic thrombus and its attachment stie, and the replaced artificial blood vessel had anticoagulated properties, no anticoagulation treatment was required for this patient. The CTA scan at the 3-month follow-up confirmed the stability of the grafts without a recurrence of an aortic thrombus.

Discussion and conclusions

To the best of our knowledge, such a large floating thrombus in the ascending aorta that has not caused devastating complications has rarely been reported. The pathophysiological mechanisms of AMT remain unclear, although coagulopathy, immunological disorders, malignancies, intra-aortic atheroma, aortic structural abnormalities, trauma, steroid use, and substance abuse have all been suggested as possible causes [5, 6]. This was not the case for our patient, however.

Because of the rarity of the disease and the fact that many patients are asymptomatic before significant embolic events occur [7], early diagnosis of a floating aortic thrombus is difficult, and there is no accurate incidence rate of AMTs. In a study of 10,671 consecutive autopsies, however, the incidence of non-aneurysmal AMT was found to be about 0.45%, higher in women than in men [4].In this patient, who was admitted to our emergency unit for chest pain. The emergency ECG and laboratory test eliminated acute myocardial ischemia. CTA showed no aneurysm or aortic dissection, except for a floating thrombus in the ascending aorta. It's not clear whether chest pain has a causal relationship with the aortic mural thrombus, but the floating aortic thrombus does need further treatment.

AMTs are prone to break off, thus carrying a potential risk of cerebral, peripheral, or visceral embolic events with catastrophic consequences [8, 9]. The most common embolic site is the lower extremity artery, with the next most common sites being the mesenteric and renal arteries. The rarest embolic sites are the cerebral and coronary arteries, but these were often the most lethal and seriously affected the prognosis [9, 10]. Toyama et al. believed that the risk of thromboembolism is related to the size of the aortic thrombus base and the degree of calcification, but not to the location of attachment or volume of the thrombus [11]. The risk of peripheral or visceral embolism is 12% in a sessile thrombus, while it is 73% in a floating thrombus [4]. Approximately 6% of AMT may be the direct cause of death [1]. To describe the hemodynamic features and evaluate the break-off potential of lesions, Ruggero De Paulis et al. have defined a new parameter called the break-off risk ratio (boRR) [12]. This parameter refers to the length ratio of the floating and attached portions of the lesion, and a higher value indicates a higher possibility of the lesion breaking off. This may help in the selection of management strategies. However, further studies are required to verify this parameter’s significance.

A diagnosis of AMT mainly depends on imaging examinations. CTAs are conducive to locating aortic thrombi and judge whether there is an asymptomatic peripheral or visceral embolism, as well as its location [13], but the contrast agent and radiation are harmful. Transthoracic or transesophageal echocardiographies also have high accuracy rates and can evaluate the size, shape, attachment position, and aortic wall characteristics of thrombi located in the proximal ascending aorta [6]. However, a thrombus in the distal part of the ascending aorta and/or aortic arch cannot be accurately evaluated by echocardiography, due to the interference of gas in the trachea. In addition, magnetic resonance imaging has been reported to aid in the diagnosis of aortic thrombi and can help to exclude the possibility of malignancy [5]. This patient had a past medical history of acute right lower extremity embolism three years ago, which may come from the floating aortic thrombus. However, as limited by less clinical experience or some other reasons, the local hospital which performed previous surgical leg embolectomy didn’t do aorta imaging. Therefore, comprehensive and systematic preoperative examinations are very important to identify the source of embolus. In general, CTA is a first-line examination because of its convenience and high sensitivity [13]. Moreover, our case suggests that CTA, followed by transesophageal echocardiography, can provide optimal visualization of the AMT for accurate diagnosis and risk evaluation, and it is helpful in determining safer surgical procedures and the extent of resection.

With regard to treatment strategies, there is no consensus on therapeutic recommendations. A review of the literature from the past 5 years indicates that a conservative approach with anticoagulants or endovascular or open surgical interventions were all reasonable treatment options for floating aortic thrombi (Table 2), depending on their size, location, mobility, and any related peripheral embolisms. Conservative treatment is preferred and considered to be the cornerstone of successful treatment by many researchers [2, 26]. Thrombolytic drugs, like tissue plasminogen activator, can rapidly break up the thrombus, but they increase the risk of embolism as the thin attachment site, instead of the thrombus itself, may be lysed first [18]. In contrast, anticoagulants, such as warfarin and rivaroxaban, are much safer for use. Once the aortic thrombus is diagnosed, anticoagulation treatment should be started as early as possible [2]. However, some researchers have expressed concern that as many as 25% of patients treated with anticoagulants alone ultimately need surgical treatment due to continuous or recurrent thrombi [2, 29]. Additionally, the appropriate drug, dose, and treatment duration are all important factors in the conservative treatment of thrombi, but consistent guidelines for their use have not yet been established [4]. Therefore, conservative treatment is more likely to be performed in asymptomatic patients with small sessile thrombi or in those who are unable to bear surgery.

Endovascular treatment has the advantages of being minimally invasive and having fewer complications, providing a new choice for patients for whom conservative drug treatments are ineffective. However, thrombus fragmentation may be caused by guidewire movement or stent compression, which is why there is still a high rate of new embolism formation in the perioperative period. Careful management of the guidewire, at least 2 cm of the proximal and distal anchorage area, oversized less than 5%, and reassessment of the mesenteric and lower extremity artery patency at the end of the procedure are essential [4, 5]. Furthermore, adjustable sheath assisted guidewires and intravascular ultrasound promoted precise positioning of stents may help to reduce the risk of thrombus fragmentation. Andrea Siani et al. also recommended to reduce the dose and injection speed of the contrast agent and to install an intravascular filter or balloon [17]. In brief, endovascular treatment may be effective for resolving AMTs, but the long-term effect is still unknown. Surgical excision of the thrombus and aortic attachment site is another choice that the clinician has, especially when embolic events have occurred. Extracorporeal circulation and circulatory arrest are required during the therapy, however. Therefore, it is of great importance to evaluate both the perioperative risks and benefits of aortic arch surgery. It is also crucial to distinguish the floating aortic thrombus from aortic arch atheroma or debris, both of which carries a much higher perioperative risk if surgically removed. One study reported the local recurrence of a thrombus at the same attachment site after thrombectomy [18], indicating that the resection of the attachment site should be taken into consideration. Surgical resection, both of the aortic thrombus and the attachment site, became necessary for our case because the floating thrombus was so large and presented such a high risk for future embolic events.

In conclusion, floating aortic thrombi are rare, and they are prone to break off, thus carrying a potential risk for embolic events with catastrophic consequences. The pathophysiological mechanisms of AMT remain unclear, and there is no consensus on therapeutic recommendations. For a suspected ascending aortic floating thrombus, we advocate CTA, combined with transesophageal echocardiography, for a comprehensive assessment of an AMT. Surgical resection, both of the aortic thrombus and attachment site, as well as postoperative anticoagulant administration, are standard treatments. However, elderly patients or those with an extremely high risk from surgery can choose conservative drug treatment or endovascular treatment, if necessary.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AMT:

-

Aortic mural thrombus

- CTA:

-

Computed tomography angiography

- Asc:

-

Ascending aorta

- LV:

-

Left ventricle

- RV:

-

Right ventricle

- RA:

-

Right atrium

- DA:

-

Descending aorta

- PA:

-

Pulmonary artery

References

Machleder HI, Takiff H, Lois JF, Holburt E. Aortic mural thrombus: an occult source of arterial thromboembolism. J Vasc Surg. 1986;4(5):473–8.

Fayad ZY, Semaan E, Fahoum B, et al. Aortic mural thrombus in the normal or minimally atherosclerotic aorta. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27(3):282–90.

Yang S, Yu J, Zeng W, et al. Aortic floating thrombus detected by computed tomography angiography incidentally: five cases and a literature review. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(4):791–803.

Verma H, Meda N, Vora S, George RK, Tripathi RK. Contemporary management of symptomatic primary aortic mural thrombus. J Vasc Surg. 2014;60(6):1524–34.

Scott DJ, White JM, Arthurs ZM. Endovascular management of a mobile thoracic aortic thrombus following recurrent distal thromboembolism: a case report and literature review. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2014;48(3):246–50.

Noh TO, Seo PW. Floating thrombus in aortic arch. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2013;46(6):464–6.

Labsaili H, Bouaggad A, Alami AA, et al. Surgical treatment of a floating thrombus of the ascending aorta causing repeated arterial embolisms. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29(5):1021.e5-7.

Teranishi H, Tsubota H, Arai Y, Hanyu M. Floating thrombus in the ascending aorta. J Card Surg. 2016;31(8):549–50.

Ozaki N, Yuji D, Sato M, Inoue K, Wakita N. A floating thrombus in the ascending aorta complicated by acute myocardial infarction. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;65(4):213–5.

Auer J, Vorreiter G, Gurtner F, Primus C, Berent R. Massive floating thrombus in the ascending aorta. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;33(9):1443–4.

Toyama M, Nakayama M, Hasegawa M, Yuasa T, Sato B, Ohno O. Direct oral anticoagulant therapy as an alternative to surgery for the treatment of a patient with a floating thrombus in the ascending aorta and pulmonary embolism. J Vasc Surg Cases Innov Tech. 2018;4(2):170–2.

De Paulis R, Weltert L. Can we quantify the risk of embolization for a free-floating thrombus? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2017;153(4):804–5.

Wang B, Ma D, Cao D, Man X. Huge thrombus in the ascending aorta: a case report and literature review. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;14(1):157.

Schattner A, Adi M. Mobile menace: floating aortic arch thrombus. Am J Med. 2016;129(2):e23–4.

Pang PYK, Nathan VB. Successful thrombectomy for an idiopathic floating ascending aortic thrombus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2016;102(3):e245–7.

Keraliya AR, Murphy DJ, Steigner ML, Blankstein R. Thrombus in hypoplastic aorta: an uncommon cause of acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(3):263–4.

Siani A, Accrocca F, De Vivo G, Mounayergi F, Marcucci G. Endovascular treatment of symptomatic thrombus of the descending thoracic aorta. Ann Vasc Surg. 2016;36:295.e13-295.e16.

Weiss S, Bühlmann R, von Allmen RS, Makaloski V, Carrel TP, Schmidli J, et al. Management of floating thrombus in the aortic arch. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2016;152(3):810–7.

Poon SS, Nawaytou O, Hing A, Field M. Giant aortic thrombus in the ascending aorta and perforation of bowel associated with cocaine use. Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(3):e219–20.

Luetkens JA, Schild HH, Thomas DK. Massive aortic valve thrombosis with free floating thrombus following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. Eur Heart J. 2017;38(23):1855.

de Maat GE, Vigano G, Mariani MA, Natour E. Catching a floating thrombus; a case report on the treatment of a large thrombus in the ascending aorta. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;12(1):34.

Avelino MC, de Miranda CLVM, de Sousa CSM, Bastos BB, de Sousa RSM. Free-floating thrombus in the aortic arch. Radiol Bras. 2017;50(6):406–7.

Kandemirli SG, Balkanay OO, Awiwi MO, Durmaz E, Goksedef D, Comunoglu N. Thoracoabdominal aortic mural and floating thrombus extending into superior mesenteric artery. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2018;45(3):539–42.

Tigkiropoulos K, Karamanos D, Tympanidou M, Saratzis N, Lazaridis I. Aortic arch floating thrombus complicated by distal embolization in a patient with malignancy. Case Rep Vasc Med. 2018;2018:2040925.

Sosa C, Zuccarino F. Floating aortic thrombus in a non-aneurysmal and non-atherosclerotic aorta. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2018;55(4):491.

Campanile A, Sardone M, Pasquino S, Cagini A, Di Manici G, Cavallini C. Surgical management of a free-floating thrombus in the ascending aorta. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann. 2019;27(3):221–3.

Dalal AR, Kabirpour A, MacArthur JW. Surgical excision of a free floating ascending aortic thrombus. J Card Surg. 2020;35(2):429–30.

Gueldich M, Piscitelli M, Derbel H, Boughanmi K, Bergoend E, Chanai N, et al. Floating thrombus in the ascending aorta revealed by peripheral arterial embolism. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2020;30(5):762–4.

Gülcü A, Gezer NS, Men S, Öz D, Yaka E, Öztürk V. Management of free-floating thrombus within the arcus aorta and supra-aortic arteries. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2014;125:198–206.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The postoperative pathological examination and writing manuscript were funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Numbers 81670327 and 81300155). The image post-processing and video production were funded by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Grant Numbers 2019YJ0046).The image data collecting and analysis were funded by the 1·3·5 project for disciplines of excellence–Clinical Research Incubation Project, West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Grant Numbers 2019HXFH027).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors participated in the management of the patient in this case report. PY, WL and JH participated in the surgery. PY and YL drafted the manuscript. YH and CL collected clinical data and retrieved literature. WL completed the image post-processing and video production. JH supervised the case and also revised the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Patient has signed the Written informed consent for publication of this case report and any accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Video 1.

Preoperative CTA 3D reconstruction.

Additional file 2: Video 2.

The preoperative transesophageal echocardiography showed a mobile lesion on the anterior wall of the distal ascending aorta.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, P., Li, Y., Huang, Y. et al. A giant floating thrombus in the ascending aorta: a case report. BMC Surg 20, 321 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00983-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-020-00983-6