Abstract

Background

Although cavernous hemangioma is one of the most frequently encountered benign hepatic neoplasms, hepatic sclerosed hemangioma is very rare. We report a case of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma that was difficult to distinguish from an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma by imaging studies.

Case presentation

A 76-year-old male patient with right hypochondralgia was referred to our hospital. Abdominal ultrasonography revealed a heterogeneously hyperechoic tumor that was 59 mm in diameter in segment 7 of the liver. Dynamic computed tomography showed a low-density tumor with delayed ring enhancement. Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (EOB-MRI) demonstrated a low-signal intensity mass with ring enhancement on T1-weighted images. The mass had several high-signal intensity lesions on T2-weighted images. EOB-MRI revealed a hypointense nodule on the hepatobiliary phase. From these imaging studies, the tumor was diagnosed as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, and we performed laparoscopy-assisted posterior sectionectomy of the liver with lymph node dissection in the hepatoduodenal ligament. Histopathological examination revealed a hepatic sclerosed hemangioma with hyalinized tissue and collagen fibers.

Conclusion

Hepatic sclerosed hemangioma is difficult to diagnose preoperatively because of its various imaging findings. We report a case of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma and review the literatures, especially those concerning imaging findings.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The preoperative diagnosis of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma is very difficult, even with recent developments in radiological modalities, because it is an extremely rare benign disorder and its radiological features resemble those of hepatic malignancies such as cholangiocarcinoma and metastatic liver cancer [1,2]. We report a case of a hepatic sclerosed hemangioma, that had been preoperatively misdiagnosed as an intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and been resected, and review the relevant literature, especially summarizing the imaging findings of hepatic sclerosed hemaigioma.

Case presentation

A 76-year-old male patient had consulted a doctor for upper abdominal pain 16 months before being referred to us and had been followed up. Because plain computed tomography (CT) revealed a space-occupying lesion in the liver, he was referred to our hospital. A laboratory workup on admission showed that total bilirubin, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, albumin, and creatinine were all within normal ranges. Tumor markers including alpha-fetoprotein, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist-II, carcinoembryonic antigen, and carbohydrate antigens 19–9 were also within the normal limits (Table 1).

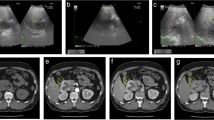

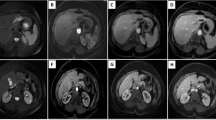

Abdominal ultrasonography (US) revealed a well-defined, heterogeneously hyperechoic mass that was 59 mm in diameter in segment 7 of the liver (Figure 1). Plain CT revealed a low-density 60-mm sized mass with an irregular margin. Dynamic CT revealed early ring enhancement in the peripheral part on the arterial phase and internal heterogeneous enhancement on the delayed phase (Figure 2). Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (EOB-MRI) showed that the tumor had low-signal intensity on T1-weighted images and that the mass had some high-signal intensity foci in the tumor on T2-weighted images. EOB-MRI showed no uptake in the corresponding area on the hepatobiliary phase and ring enhancement in the peripheral part on the arterial phase and the portal phase (Figure 3).

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). (a) T1-weighted image, (b) T2-weighted image, and (c) ethoxybenzyl (EOB)-MRI on the hepatobiliary phase. The tumor had low-signal intensity on T1-weighted and some high-signal intensity nodules in the tumor on T2-weighted images. EOB-MRI showed no uptake in the corresponding area on the hepatobiliary phase.

Laparoscopy-assisted posterior sectionectomy and cholecystectomy including lymph node dissection in the hepatoduodenal ligament were performed for a preoperative diagnosis of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. The resected specimen revealed a white solid mass, sized 61 × 46 mm. The cut surface of the tumor was elastic, soft, and homogeneous with the smooth margin including some faint red spots up to 10 mm in size (Figure 4a).

Resected specimen. (a) Surface of slice. The cut surface of the tumor reveals a white solid mass (61 × 46 mm in size) that was elastic, soft, and homogeneous with a smooth margin including some faint red spots, sized 1 cm. (b) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (magnification, ×100). The tumor was composed of fibrous connective tissue highlighted with collagen fiber and various sizes of cavernous hemangioma tissue with some hyaline degeneration secondary to thrombus, necrosis, or cicatrization.

Histopathological examination showed that the tumor was composed of fibrous connective tissue highlighted with collagen fibers and various sizes of cavernous hemangioma tissue with some hyaline degeneration secondary to thrombus, necrosis, or cicatrization, resulting in a hepatic sclerosed hemangioma (Figure 4b).

The postoperative course was uneventful. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 6.

Discussion

Hepatic sclerosed hemangioma, first reported by Ishii in 1995 [1], is a rare disease, detected and reported in only 2 out of 1000 cases on autopsy [3]. We found only 9 cases in PubMed by manual searching for the terms “hepatic, sclerosed, hemangioma” and “hepatic, sclerosing, hemangioma” from January 1983 to January 2015. Additionally, we found 22 cases in ICHUSHI, a bibliographic database established in 1903 and being updated by the Japan Medical Abstracts Society, contains bibliographic citations and abstracts from more than 2500 biomedical journals and other serial publications published in Japanese. The 32 cases, including our case, are summarized in Table 1 [1,4-33].

Hepatic sclerosed hemangioma is caused by degenerative changes such as thrombus formation, necrosis, and scar formation of liver cavernous hemangioma, but the mechanism for degenerative changes in the hepatic cavernous hemangioma has not been well clarified at present [34].

Concerning the imaging studies, Doyle et al. summarized the imaging findings of 10 hepatic sclerosed hemangioma lesions and found the characteristic features to include a geographic pattern, capsular retraction, decrease in size over time, loss of previously seen regions of enhancement [2]. And additional characteristic, features included the presence of transient hepatic attenuation difference, ring enhancement, and nodular regions of intense enhancement as seen in typical hemangioma. In our series reviewed the average size of the hepatic sclerosed hemangiomas was 42.3 mm, ranging from 10 to 145 mm. Abdominal US showed a hyperechoic mass in 11 cases and a hypoechoic tumor in 13 cases. Plain CT was likely to show a low-density mass, and dynamic CT showed ring enhancement, resembling metastatic liver cancer or intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, in 27 of 31 reported cases. MRI showed a low-intensity signal in 24 of 26 reported cases on T1-weighted images and a high-intensity signal in 22 of 26 reported cases on T2-weighted images. The radiological features revealed by dynamic CT and MRI resembled those of hepatic malignancies, leading to preoperative misdiagnosis. Whereas, [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), performed in just 6 cases, showed no accumulation of [18F]-FDG (Table 1). FDG-PET could be helpful in preoperative diagnosis to distinguish benign sclerosed hemangioma from malignant tumors such as intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas or metastatic liver cancers. We may have had to perform FDG-PET preoperatively.

Surgical resection for hepatic sclerosed hemangioma is controversial. Most of the tumors reported were resected due to a preoperative misdiagnosis of malignancy (Table 1). To make a definite diagnosis of such hepatic tumors, percutaneous needle biopsy is not acceptable because of the possibility of dissemination of the cancer cells if the tumor is malignant. Therefore we would suggest that hepatic resections are chosen for the management of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma at present.

Makhlouf and Ishak compared the findings of sclerosed hemangioma and sclerosing cavernous hemangioma. According to their theory, recent hemorrhages and hemosiderin deposits rich in mast cells are present in the sclerosing hemangioma. While, fibrosis, increased elastic fibers, and dystrophic or psammomatous calcifications with a decreased number of mast cells can be observed in the sclerosed hemangioma [35]. Our case showed a fibrous connective tissue highlighted with collagen fibers and various sizes of cavernous hemangioma tissue with some hyaline degeneration. These findings are consistent with features of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma, resulting in the final diagnosis.

Conclusion

We report a case with a hepatic sclerosed hemangioma. Although it is a rare disease, it is important to distinguish hepatic sclerosed hemangioma from hepatic malignancies. However, it is extremely difficult to diagnose precisely from imaging studies. If the possibility of a malignant tumor cannot be ruled out, hepatic resection might be selected for diagnostic therapy.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Abbreviations

- EOB-MRI:

-

Gadolinium-ethoxybenzyl-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- US:

-

Ultrasonography

- FDG-PET:

-

[18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

References

Ishii T, Takahara O, Sano I, Taniguchi H, Nakao S, Eida K, et al. Sclerosing Hemangioma of the liver. Nagasaki Med J. 1995;70(1):23–6.

Doyle DJ, Khalili K, Guindi M, Atri M. Imaging features of sclerosed hemangioma. Am J Roentgenol. 2007;189(1):67–72.

Berry CL. Solitary “necrotic nodules” of the liver: a probable pathogenesis. J Chin Pathol. 1985;38(11):1278–90.

Haratake J, Arai K, Makino H. Hemangioma and hyalinized hemangioma. Jpn J Clin Med. 1995;7:336–8.

Kobayashi S, Demachi H, Akakura Y, Miyata S, Konishi K, Tsuji M, et al. A case of sclerosing cavernous hemangioma of the liver. Jpn J Clin Radiol. 1996;41:567–70.

Ukai K, Onidera H, Mikuni J, Ouchi K. A case of sclerosed hemangioma of the liver. Liver. 1998;39(9):638–42.

Yamashita Y, Shimada M, Taguchi K, Gion T, Hasegawa H, Utsunomiya T, et al. Hepatic sclerosing hemangioma mimicking a metastatic liver tumor: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30:849–52.

Okada S, Tsuyama H, Kurita K, Onchi H, Inoue T, Kinoshita K, et al. A case of sclerosing hemangioma with cancer of the desending colon. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2001;62(3):757–60.

Aibe H, Honda H, Kuroiwa T, Yoshimitsu K, Irie H, Tajima T, et al. Sclerosed hemangioma of the liver. Abdom Imaging. 2001;26:496–9.

Hayakawa T, Itou M, Taniguchi S, Ideno M, Konno T, Hatayama J. A case of sclerosing hemangioma of the liver. J Med Assoc South Hokkaido. 2001;38:180–3.

Lee VT, Magnaye M, Tan HW, Thng CH, Ooi LL. Sclerosing haemangioma mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma. Singapore Med J. 2005;46(3):140–3.

Morikawa M, Ishida M, Iida A, Katayama K, Yamaguchi A, Imamura Y. Sclerosed hemangioma of the liver mimicking metastatic liver cancer. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2005;66(7):1698–702.

Okamoto E, Satou S, Takahashi Y, Ohshima N, Azumi T, Furuta K, et al. A case of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma in patient with fatty liver. J Shimane Med Assoc. 2005;25(3):60–4.

Hamatsu T, Kuroda Y, Hunahashi S, Shima I, Iso Y. Sclerosed hemangioma of the liver mimicking metastatic liver tumor of colon cancer. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2006;67(4):856–60.

Hayashi K, Ohara H, Kitajima Y, Tanaka S, Takada H, Imai E, et al. A case of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma mimicking gastric submucosal tumor. Kanzo. 2006;47(10):474–81.

Iida H, Tango Y, Tsutamoto Y, Harimura T, Tanaka K, Takao T, et al. A resected case of Sclerosed hemangioma. Jpn J Gastroenterol Surg. 2006;39(9):1493–7.

Sawai K, Ueda N, Senda K, Kimura T, Sawa T. A case of sclerosing hemangioma of the liver. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2007;68(9):2293–8.

Kaji S, Koike N, Suzuki S, Harada N, Suzuki M, Hanyu F. A case of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma mimicking cholangiocell carcinoma. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2008;69(5):1181–5.

Tsumaki N, Waguri N, Yoneyama O, Hama I, Kawahisa J, Yokoo K, et al. A case of hepatic sclerosed hemangioma with a significant morphological change over a period of 17 years. Kanzo. 2008;49(6):268–74.

Mori H, Ikegami T, Imura S, Shimada M, Morine Y, Kanemura H, et al. Sclerosed hemangioma of the liver: report of a case and review of the literature. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:529–33.

Yoshida T, Sugimachi K, Gion T, Soejima Y, Aijima S, Takatomi S, et al. A case of sclerosing hemangioma mimicking a malignant liver tumor. J Clin Surg. 2010;65(3):451–5.

Usui T, Shiozawa S, Kim DH, Tsuchiya A, Kuhara K, Yokomizo H, et al. A case of sclerosed hemangioma mimicking a metastatic liver tumor. J Jpn Coll Surg. 2010;35(1):89–93.

Jin S-Y. Sclerosed hemangioma of the liver. Korean J Hepatol. 2010;16(4):410–3.

Hida T, Nishie A, Tajima T, Taketomi A, Aishima S, Honda H. Sclerosed hemangioma of the liver: possible diagnostic value of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging. Jpn J Radiol. 2010;28:235–8.

Miyaki D, Aikata H, Waki K, Murakami E, Hashimoto Y, Nagaoki Y, et al. Significant regression of a cavernous hepatic hemangioma to a sclerosed hemangioma over 12 years: a case study. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi. 2011;108(6):954–61.

Kitami C, Kawachi Y, Nishimura A, Makino S, Kawahara M, Nikuni K. Sclerosed hemangioma of the liver -report of a case-. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2011;72(12):3120–4.

Tanaka T, Moriya T, Fukuda S, Yoshifuku Y, Fujino H, Miwata T, et al. A case of sclerosed hemangioma of the liver was difficult to differentiate hepatocellular carcinoma was found during examination of chronic hepatitis C. HBP Imaging. 2011;13(6):646–52.

Mikami J, Tominaga M, Sendo H, Maeda Y, Fujino Y, Koma Y, et al. A case of hepatic sclerosing hemangioma mimicking a malignant liver tumor. J Jpn Surg Assoc. 2011;72(4):965–71.

Shin YM. Sclerosing hemangioma in the liver. Korean J Hepatol. 2011;17(3):242–6.

Wakasugi M, Ueshima N, Akamatsu D, Tori M, Tsujimoto M, Nishida T. A case of multiple sclerosed hemangioma mimicking a metastatic liver tumor. J Clin Surg. 2012;67(12):1461–5.

Yamada S, Shimada M, Utsunomiya T, Morine Y, Imura S, Ikemoto T, et al. Hepatic sclerosed hemangioma which was misdiagnosed as metastasis of gastric cancer : report of a case. J Med Invest. 2012;59:270–4.

Song JS, Kim YN, Moon WS. A sclerosing hemangioma of the liver. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2013;19(4):426–30.

Shimada Y, Takahashi Y, Iguchi H, Yamazaki H, Tsunoda H, Watanabe M, et al. A hepatic sclerosed hemangioma with significant morphological change over a period of 10 years: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2013;28(7):139.

Goodman ZD. Benign tumors of the liver. In: Okuda K, Ishak KG, editors. Neoplasm of the liver. Tokyo: Springer; 1987. p. 105–25.

Makhlouf HR, Ishak KG. Sclerosed hemangioma and sclerosing cavernous hemangioma of the liver: a comparative clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study with emphasis on the role of mast cells in their histogenesis. Liver. 2002;22(1):70–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

The first two authors contributed equally to this work. SM drafted the paper and collected date and reviewed the text. AO performed the operation, helped SM to draft the paper and made the final revision. YD diagnosed this disease. MS and AN assisted the operation. HO made the expert assistance. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Miyamoto, S., Oshita, A., Daimaru, Y. et al. Hepatic Sclerosed Hemangioma: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Surg 15, 45 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-015-0029-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12893-015-0029-x