Abstract

Background

Atraumatic full thickness rotator cuff tears (AFTRCT) are common lesions whose incidence increases with age. Physical therapy is an effective conservative treatment in these patients with a reported success rate near 85% within 12 weeks of treatment. The critical shoulder angle (CSA) is a radiographic metric that relates the glenoid inclination with the lateral extension of the acromion in the coronal plane. A larger CSA has been associated with higher incidence of AFTRCT and a higher re-tear rate after surgical treatment. However, no study has yet described an association between a larger CSA and failure of conservatory treatment in ARCT. The main objective of this study is to determine whether there is an association between CSA and failure of physical therapy in patients with AFTRCT.

Methods

We reviewed the imaging and clinical records of 48 patients (53 shoulders), 60% female, with a mean age of 63.2 years (95% CI ± 10.4 years); treated for AFTRCT who also underwent a true anteroposterior radiograph of the shoulder within a year of diagnosis of the tear. We recorded demographic (age, sex, type of work), clinical (comorbidities), and imaging data (CSA, size and location of the tear). We divided the patients into two groups according to success or failure of conservative treatment (indication for surgery), so 21 shoulders (39.6%) required surgery and were classified as failure of conservative treatment.

Univariate and multivariate analysis was performed to detect predictors of failure of conservative treatment.

Results

The median CSA was 35.5º with no differences between those with failure (median 35.5º, range 29º to 48.2º) and success of conservative treatment (median 35.45º, range 30.2º to 40.3º), p = 0.978.

The multivariate analysis showed a younger age in patients with failure of conservative treatment (56.14 ± 9.2 vs 67.8 ± 8.4, p < 0.001) and that male gender was also associated with failure of conservative treatment (57% of men required surgery vs 28% of women, p = 0.035).

Conclusions

It is still unclear if CSA does predict failure of conservative treatment. A lower age and male gender both could predicted failure of conservative treatment in AFTRCT. Further research is needed to better address this subject.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Atraumatic full thickness rotator cuff tears (AFTRCT) are frequent lesions whose incidence increases with age affecting more than 10% of patients over 60 years old [1]. Nevertheless, there is no consensus regarding the best treatment choice for these patients, and there are some debates about absolute indications of surgery [2].

Previous literature has shown that physical therapy is an effective conservative treatment in this group of patients [3, 4] with a success rate near 85% within 12 weeks of treatment (failure defined as patients choosing surgical treatment), with several factors affecting outcomes [5]. In an effort to identify predictors of failure in the conservative treatment of AFTRCT, Dunn et al. [6]. in a Neer award study showed that the main predictors were activity level, smoking status, and low patient expectations about physical therapy, while structural factors like tear size or retraction were not.

AFTRCT are a multifactorial pathology, and the influence of acromial geometry was described by Neer [7] in terms of subacromial impingement. Nyffeler [8]described an association between AFTRCT and a large lateral acromial extension, postulating that a more vertical deltoid force pulling the humeral head upward requires a larger supraspinatus counterforce to stabilize the center of rotation during abduction [9]. This concept was revisited by Moor et al. [10] who combined the lateral extension of the acromion and the upward inclination of the glenoid in a single measurement named the critical shoulder angle (CSA).

The CSA is a simple and reproducible radiographic measure made between a line connecting the superior and inferior margins of the glenoid, and another line connecting the inferior margin of the glenoid with the inferolateral aspect of the acromion (Fig. 1) in a true anteroposterior (AP) view of the shoulder.

Gerber et al. [11] and Viehöfer et al. [12] demonstrated that a greater CSA increased shear forces at the glenohumeral joint, ant suggested that this could produce a mechanical overload of the supraspinatus tendon in order to stabilize the glenohumeral joint during arm elevation.

In clinical context, some studies have shown an association between CSA and incidence of AFTRCT [13,14,15,16,17], and others have found an association of a large CSA and a higher risk of tendon retear [18,19,20].

With this previous work as backround, it might raise the question wether a larger CSA could impact clinical outcomes in the treatment of AFTRCT, more specifically, if it could predict success or failure of conservative treatment.

However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has yet described an association between a larger CSA and failure of conservatory treatment in AFTRCT.

Therefore, the main objective of this study is to determine whether there is an association between CSA and failure of physical therapy in patients with AFTRCT.

Methods

Patient selection and study design

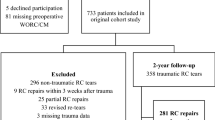

Our study was performed following the STROBE statement for cohort studies and the Declaration of Helsinki. Our ethical committee approved the patient registry. This was an observational, retrospective, consecutive, monocentric, continuous multi-operator study. We reviewed data from 356 adult patients consecutively treated for an isolated full thickness posterosuperior tear diagnosed by magnetic resonance (MR) or ultrasound (US) who also underwent a true anteroposterior (AP) radiograph of the shoulder less than a year since diagnosis in a tertiary care university hospital and its primary care network from 2017 to 2018.

The patients underwent more than one image study during the review period, and only their first was used for the evaluation. The definition of AFTRCT included tears of the supraspinatus tendon extending or not to the infraspinatus tendon. Medical records were analyzed for presence of shoulder symptoms, history of trauma, comorbidities, tobacco use, physical therapy achieved, and indication of surgery within one year of the diagnostic image (definition of failure of physical therapy in patients with AFTRCT).

We excluded patients with asymptomatic tears, clear indication for surgery (eg traumatic tears), prior shoulder surgery, other causes of shoulder pain like infection, degenerative osteoarthritis, capsulitis, instability, and calcific tendonitis, and tumors. We also excluded patients that could not correctly adhere to the standardized physical therapy protocol. A total of 303 patients were excluded (Table 1) leaving 53 shoulders for statistical analysis.

Demographic data

Fifty-three shoulders of 48 patients were included: 28 were left shoulders (52.8%) and 32 patients were female (60.4%). Their mean age at the time of surgery was 63.2 years (range, 30–88 years). The demographic factors are listed in Table 2.

Radiographical measurements

The CSA was calculated using the technique described by Moor et al. [10] The angle was formed by a line connecting the superior and inferior bony margins of the glenoid and a line drawn from the inferior bony margin of the glenoid to the most lateral border of the acromion using the true AP shoulder radiograph (glenohumeral joint should be open; anterior and posterior aspects of the glenoid are superimposed; coracoid process is foreshortened; and no foreshortening of the scapular body). We used a cutoff of 0.25 between the transverse and longitudinal diameter of the glenoid to quantitively define a true AP view as described by Hou et al. [21].

Five evaluators (three orthopedic surgery residents, one shoulder and elbow surgery fellow, and one shoulder and elbow surgeon with 10 years of experience) independently measured each patient CSA; the mean of the four measures was used as the final result. All radiographs were obtained using a digital imaging system. The images were viewed using the Impax Web3000 program (Agfa-Gevaert, Mortsel, Belgium), which is routinely used at our institution with backup from a radiologist.

Statistical analysis

The results are presented according to the type of variable and distribution: Continuous nonparametric data were described as median values and range, continuous parametric data were described as mean and standard deviation, and categorical variables were expressed as percentages. A univariate analysis was performed to find statistically significant differences (p-value less than 0.05) according to the dependent variable "Failure of conservative treatment" was defined as “indication of surgery within one year of the diagnostic image”. In this analysis, normal distribution was verified with the Shapiro–Wilk test. In those variables with normal distribution, an unpaired t-test with Welch's correction was used. The non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used in variables without a normal distribution. Fisher's exact test was used to compare contingency tables.

In addition, three multivariate analysis was performed for the binary dependent variable "failure of conservative treatment” using logistic regression (LR) to adjust for possible covariances: LR1 included the independent variables "CSA", "Age", "Gender", and "Tobacco use"; LR2 included the independent variables "CSA", "Age", "Gender", and "Manual worker"; and LR3 included the independent variables "CSA", "Age", "Gender", and "Location of tendon tear". Statistical analysis was performed using STATA software (version BE 17; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Of the 53 shoulders, 21 required surgery within one year of the diagnostic image and therefore were classified as failure of conservative treatment (39.6%). We measured a median CSA of 35.5 in the 53 shoulders, and there were no differences between patients who failed conservative treatment (median 35.5, range 29 to 48.2) and those who succeeded (median 35.45, range 30.2 to 40.3), p = 0.978 (post-hoc statistical power between 88.8 – 69.7%).

In relation to demographic and general parameters, we found that age was lower in patients who failed conservative treatment (56.14 ± 9.2, vs 67.8 ± 8.4, p-value < 0.001); that genre was also associated with failure of conservative treatment (57% of male patients required surgery, vs 28% of female patients, p = 0.035). Shoulder involvement, extension to the tear to the infraspinatus, manual working, tobacco use, diabetes, and hypothyroidism were not associated with failure of conservative treatment (Table 2). Multivariate analysis confirmed the association between age and gender in all settings. CSA was not associated with changes in failure of conservative management in any analysis.

Discussion

In our study, we could not find an association between the magnitude of the CSA and the failure of conservative treatment in atraumatic full thickness rotator cuff tears, but instead we found that a lower age and male sex both could predict failure of conservative treatment. Our results differ from those presented by Dunn et al. [6] who found an association between tobacco use and failure of conservative treatment in AFTRCT, but failed to demonstrate an association between age and sex.

AFTRCT are lesions frequently seen in people over 60 years old, but it is still unclear what the best treatment option is for such injuries. However, more than 85% of these patients will have improved symptoms with physical therapy.

Acromial morphology has long been associated with rotator cuff disease. Initially, impingement syndrome was described as a causative factor to bursal side rotator cuff tear as proposed by Bigliani and Neer [22, 23]. This hypothesis postulated that the anterolateral narrowing of the supraspinatus outlet due to changes in acromial morphology creates an abrading effect on the rotator cuff leading to a subsequent tear. However, several authors concluded that acquired changes within the acromion and coracoacromial ligament impact rotator cuff disorders rather than cause the disorders [24,25,26,27]. Finally, randomized clinical trials [28] and a meta-analysis [29] demonstrated no difference in outcome and failure rate between repairs regardless of whether an anterolateral acromioplasty was performed.

Nyffeler et al. [8] proposed a theory based on the lateral extension of the acromion and the resulting vertical force of the acromion during abduction; increased strain or shear force was needed to stabilize the humeral head by the supraspinatus. The authors found an association between a large lateral extension of the acromion and symptomatic rotator cuff tears. A superior glenoid orientation also accounts for this phenomena, and its association with rotator cuff tears has also been demonstrated [30,31,32].

Moor et al. [10] developed the CSA to consider both components in a single angle. In their milestone paper, this group reported a larger CSA (38º vs 31º) in patients with degenerative rotator cuff tears compared with controls and postulated that CSA may be a risk factor for developing degenerative rotator cuff tears. Several authors have accounted for this relationship [13, 33,34,35,36,37].

Biomechanical models have demonstrated the mechanistic basis of the pathology of rotator cuff tears underlying the scapular anatomical differences. Gerber et al. [11] used a simplified robotic model to document that a greater CSA increased shear forces (decreased compressive forces) at the glenohumeral joint requiring an 35% additional force of the supraspinatus to achieve stability at relatively low angles of thoraco-humeral abduction (40º). In a 3D Finite element model, Viehöfer et al. [12] demonstrated that a higher CSA has a substantial effect on the middle deltoid wrapping and force of action leading to a higher shear and smaller joint compression force during active abduction. Those studies suggested that a smaller CSA requires a lower rotator cuff force to provide glenohumeral stability during active elevation.

Furthermore, it is possible that an individual with a rotator cuff tear and a smaller CSA would be more prone to compensate this instability with other co-contracting muscles and have a favorable outcome; in other scenarios, a patient with a higher CSA would be more difficult to compensate and stabilize the shear forces of the deltoid with the other co-contracting muscles. However, this hypothesis has not been confirmed here.

Our study has several limitations

First, it is a retrospective study of patients at a single tertiary care university hospital and its network. Due to our strict inclusion criteria, we had to exclude most patients initially selected. Moreover, we studied only patients with posterosuperior tears (tear of the supraspinatus extending or not to the infraspinatus). Patients with subscapularis tears were excluded. As a result, we only included 53 patients in our final analysis, and this could lead to selection bias in favor of patients with failure of conservative treatment, and this could explain why we observed a smaller proportion of patient who responded to conservative treatment compared to previous studies.

Second, our sample size was small, and the post hoc analysis we observed a power of only 20%.

Third, it is known that the treatment decision in AFTRCT is multifactorial and involves factors such as the patient's lifestyle, expectations, degree of pain and dysfunction, clinical findings (eg range of motion, pseudoparalysis, weakness) and structural findings tear (size, retraction, degree of glenohumeral osteoarthritis).

Taking this into account, trying to predict the failure of conservative treatment in this pathology using a single structural factor such as CSA could be simplistic. For this reason, also taking into account our low sample size the low quality of evidence provided by a retrospective study, we believe that studies with higher quality of evidence and involving more factors are required to more holistically determine the factors associated with failure of conservative treatment in AFTRCT. We hope that our work can be used as a basis for future studies on this subject, as maybe with the same method and more sample size a better conclusion could be made. We also summarized previous literature on the subject.

Conclusions

It is still unclear if CSA does predict failure of conservative treatment. A lower age and male gender both could predicted failure of conservative treatment in AFTRCT. Further research is needed to better address this subject.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AFTRCT:

-

Atraumatic full thickness rotator cuff tears

- MR:

-

Magnetic resonance

- US:

-

Ultrasound

- AP:

-

Anteroposterior

- CSA:

-

Critical shoulder angle

References

Reilly P, Macleod I, Macfarlane R, Windley J, Emery RJH. Dead men and radiologists don’t lie: a review of cadaver and radiologic studies of rotator cuff tear prevalence. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88:116–21. https://doi.org/10.1308/003588406X94968 [PubMed: 16551396].

Dunn WR, Schackman BR, Walsh C, Lyman S, Jones EC, Warren RF, et al. Variation in orthopaedic surgeons’ perceptions about the indications for rotator cuff surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:1978–84.

Ainsworth R, Lewis JS. Exercise therapy for the conservative management of full thickness tears of the rotator cuff: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(4):200–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2006.032524.

Kuhn JE. Exercise in the treatment of rotator cuff impingement: a systematic review and a synthesized evidence-based rehabilitation protocol. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(1):138–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2008.06.004

Kuhn, John E et al. “Effectiveness of physical therapy in treating atraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a multicenter prospective cohort study.” J Shoulder Elbow Surg. vol. 22,10 (2013): 1371–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.026

Dunn WR, Kuhn JE, Sanders R, An Q, Baumgarten KM, Bishop JY, Brophy RH, Carey JL, Harrell F, Holloway BG, Jones GL, Ma CB, Marx RG, McCarty EC, Poddar SK, Smith MV, Spencer EE, Vidal AF, Wolf BR, Wright RW; MOON Shoulder Group. 2013 Neer Award: predictors of failure of nonoperative treatment of chronic, symptomatic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016 Aug;25(8):1303–11. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jse.2016.04.030. PMID: 27422460.

Neer CS. Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;173:70–7.

Nyffeler RW, Werner CM, Sukthankar A, Schmid MR, Gerber C. Association of a large lateral extension of the acromion with rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 2006;88-A:800–805.

Inman VT, Saunders JB, Abbott LC. Observation on the function of the shoulder joint. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1944;26-A:1–30.

Moor BK, Bouaicha S, Rothenfluh DA, Sukthankar A, Gerber C. Is there an association between the individual anatomy of the scapula and the development of rotator cuff tears or osteo- arthritis of the glenohumeral joint? A radiological study of the critical shoulder angle. Bone Joint J 2013, 95-B:935–941

Gerber C, Snedeker JG, Baumgartner D, Viehöfer AF. Supraspinatus tendon load during abduction is dependent on the size of the critical shoulder angle: A biomechanical analysis. J Orthop Res. 2014;32(7):952–7. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.22621.

Viehöfer AF, Gerber C, Favre P, Bachmann E, Snedeker JG. A larger critical shoulder angle requires more rotator cuff activity to preserve joint stability. J Orthop Res. 2016;34(6):961–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.23104 Epub 2015 Dec 29 PMID: 26572231.

Spiegl UJ, Horan MP, Smith SW, Ho CP, Millett PJ. The critical shoulder angle is associated with rotator cuff tears and shoulder osteoarthritis and is better assessed with radiographs over MRI. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(7):2244–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00167-015-3587-7 Epub 2015 Mar 29 PMID: 25820655.

Lin CL, Chen YW, Lin LF, Chen CP, Liou TH, Huang SW. Accuracy of the Critical Shoulder Angle for Predicting Rotator Cuff Tears in Patients with Nontraumatic Shoulder Pain. Orthop J Sports Med. 2020;8(5):2325967120918995. Published 2020 May 15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2325967120918995

Docter S, Khan M, Ekhtiari S, et al. The relationship between the critical shoulder angle and the incidence of chronic, full-thickness rotator cuff tears and outcomes after rotator cuff repair: a systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2019;35(3135–3143): e3134.

Pandey V, Vijayan D, Tapashetti S, et al. Does scapular morphology affect the integrity of the rotator cuff? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25:413–21.

Shinagawa K, Hatta T, Yamamoto N, et al. Critical shoulder angle in an East Asian population: Correlation to the incidence of rotator cuff tear and glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:1602–6.

Li H, Chen Y, Chen J, Hua Y, Chen S. Large critical shoulder angle has higher risk of tendon retear after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(8):1892–900. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546518767634 Epub 2018 May 3 PMID: 29723034.

Opsomer GJ, Verstuyft L, Muermans S. Long-term follow-up of patients with a high critical shoulder angle and acromion index: is there an increased retear risk after arthroscopic supraspinatus tendon repair? JSES Int. 2020;4(4):882–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jseint.2020.07.010.PMID:33345229;PMCID:PMC7738603.

Franceschetti E, Giovannetti de Sanctis E, Palumbo A, Ranieri R, Casti P, Mencattini A, Maffulli N, Franceschi F. Lateral acromioplasty has a positive impact on rotator cuff repair in patients with a critical shoulder angle greater than 35 degrees. J Clin Med. 2020 Dec 5;9(12):3950. doi: https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm9123950. PMID: 33291482; PMCID: PMC7762128.

Hou J, Li F, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Tang Y, Yang R. The ratio of the transverse to longitudinal diameter of the glenoid projection is of good predictive value for defining the reliability of critical shoulder angle in nonstandard anteroposterior radiographs. Arthroscopy. 2021;37(2):438–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arthro.2020.08.036.

Bigliani LU, Morrison DS, April EW. The morphology of the acromion and its relationship to rotator cuff tears. Orthop Trans. 1986;10:228.

Neer CS 2nd. Anterior acromioplasty for the chronic impingement syndrome in the shoulder: a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1972;54(1):41–50.

Nicholson GP, Goodman DA, Flatow EL, Bigliani LU. The acromion: morphologic condition and age-related changes. A study of 420 scapulas. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5(1):1–11.

Ozaki J, Fujimoto S, Nakagawa Y, Masuhara K, Tamai S. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(8):1224–30.

Shah NN, Bayliss NC, Malcolm A. Shape of the acromion: congenital or acquired—a macroscopic, radiographic, and microscopic study of acromion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(4):309–16.

Wang JC, Shapiro MS. Changes in acromial morphology with age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6(1):55–9.

Ketola S, Lehtinen JT, Arnala I. Arthroscopic decompression not recommended in the treatment of rotator cuff tendinopathy: a final review of a randomised controlled trial at a minimum follow-up of ten years. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B(6):799–805.

Chahal J, Mall N, MacDonald PB, Van Thiel G, Cole BJ, Romeo AA, Verma NN. The role of subacromial decompression in patients undergoing arthroscopic repair of full-thickness tears of the rotator cuff: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(5):720–7 Epub 2012 Feb 2.

Hughes RE, Bryant CR, Hall JM, Wening J, Huston LJ, Kuhn JE, Carpenter JE, Blasier RB. Glenoid inclination is associated with full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003;407:86–91.

Tetreault P, Krueger A, Zurakowski D, Gerber C. Glenoid version and rotator cuff tears. J Orthop Res. 2004;22(1):202–7.

Wong AS, Gallo L, Kuhn JE, Carpenter JE, Hughes RE. The effect of glenoid inclination on superior humeral head migration. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(4):360–4.

Cherchi L, Ciornohac JF, Godet J, Clavert P, Kempf JF. Critical shoulder angle: measurement reproducibility and correlation with rotator cuff tendon tears. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2016;102(5):559–62 Epub 2016 May 26.

Miswan MF, Saman MS, Hui TS, Al-Fayyadh MZ, Ali MR, Min NW. Correlation between anatomy of the scapula and the incidence of rotator cuff tear and glenohumeral osteoarthritis via radiological study. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2017;25(1):2309499017690317.

Balke M, Liem D, Greshake O, Hoeher J, Bouillon B, Banerjee M. Differences in acromial morphology of shoulders in patients with degenerative and traumatic supraspinatus tendon tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2016;24(7):2200–5 Epub 2014 Dec 30.

Blonna D, Giani A, Bellato E, Mattei L, Calo ́ M, Rossi R, Castoldi F. Predominance of the critical shoulder angle in the pathogenesis of degenerative diseases of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016 Aug;25(8):1328–36. Epub 2016 Feb 15.

Daggett M, Werner B, Collin P, Gauci MO, Chaoui J, Walch G. Correlation between glenoid inclination and critical shoulder angle: a radiographic and computed tomography study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(12):1948–53 Epub 2015 Sep 6.

Acknowledgements

Unidad de Investigación de Traumatología Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile

Funding

No funding was required in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M: collection of data, confection of database, manuscript writing.- J.C: statistical analysis, manuscript writing A.V: data collection B.D: data collection A.T: data collection R.D: manuscript editing C.C: manuscript editing F.S: manuscript editing R.L: collection of data, manuscript writing, manuscript edition. “The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.”

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, ID Nr 201102002 (certificate included in related files), in accordance with the latest version of the Helsinki Statement. No informed consent was used in this publication. A informed consent waiver was used instead since all data was encrypted and anonymized, following the guidelines of the ethics committee of Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Meissner-Haecker, A., Contreras, J., Valenzuela, A. et al. Critical shoulder angle and failure of conservative treatment in patients with atraumatic full thickness rotator cuff tears. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 23, 561 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05519-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-022-05519-y