Abstract

Background

Musculoskeletal pain is a risk factor for leaving the labour market temporarily and permanently. While the presence of multi-site pain increases the risk of disability pension, we lack detailed knowledge about pain intensity as a risk factor. This study investigated the association between musculoskeletal pain intensity in different body regions and risk of future disability pension among eldercare workers.

Methods

Eight thousand seven hundred thirty-one female eldercare workers replied to a questionnaire on work and health in 2005 and were followed for 11 years in the Danish Register for Evaluation of Marginalization. Time-to-event analyses estimated hazard ratios (HR) for disability pension from pain intensities (0–9 numeric rating scale (NRS)) in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees during the previous 3 months. Analyses were mutually adjusted for pain regions, age, education, lifestyle, psychosocial work factors, and physical exertion at work.

Results

During 11-year follow-up, 1035 (11.9%) of the eldercare workers received disability pension. For all body regions among all eldercare workers, dose-response associations were observed between higher pain intensity and risk of disability pension (p < 0.001). The risk for disability pension was increased when reporting “very high” pain levels (≥7 points on the 0–9 NRS) in the low-back (HR 2.19, 95% CI 1.70–2.82), neck/shoulders (HR 2.34, 95% CI 1.88–2.92), and knees (HR 1.89, 95% CI 1.44–2.47). Population attributable risks (PAR) were 15.5, 23.2, and 9.6% for pain > 2 on NRS in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees, respectively, indicating that 15.5, 23.2, and 9.6% fewer eldercare workers would likely receive disability pension if the pain intensity was reduced to 2 or less. For workers ≤45 years and > 45 years, PAR was highest for neck/shoulder pain (27.6%) and low-back pain (18.8%), respectively.

Conclusions

The present study found positive dose-response associations between pain intensity in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees, and risk of disability pension during 11-year follow-up. Moderate to very high levels of musculoskeletal pain in eldercare workers should, therefore, be considered an early warning sign of involuntary premature exit from the labour market. These findings underscore the importance of preventing, managing, and reducing musculoskeletal pain to ensure a long and healthy working life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The gradually increasing statutory pension age in most European countries increases the necessity of staff retention and thus maintenance of good health of an aging workforce. However, musculoskeletal pain is common in the working population and the prevalence of pain increases with age [1]. More specifically, workers with physically demanding occupations are at a particularly high risk of both musculoskeletal pain [2, 3], long-term sickness absence, and disability pension compared to workers within more sedentary occupations [4,5,6]. Granted that both age and physically demanding work are predictors of musculoskeletal pain, these factors – especially in combination – constitute significant risk factors for being unable to work until statutory pension age. In fact, musculoskeletal pain located in different body regions, such as low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees has been associated with reduced work ability in a dose-response fashion [7, 8] and elevated risk of sickness absence [9, 10], both of which being associated with an increased risk of disability pension [11,12,13,14]. In accordance, two recent studies found musculoskeletal pain to be associated with an increased risk of disability pension [15, 16], one of which reporting a dose-response association between number of pain regions and increased risk of disability pension [15]. Thus, workplaces should be aware of workers in pain and aim to prevent and reduce the incidence of musculoskeletal pain among the workers.

Certain job groups report particularly high physical work demands and prevalence of musculoskeletal disorders. One of these job groups are healthcare workers who are at increased risk of musculoskeletal pain [17,18,19], sickness absence [9, 20], and disability pension [21,22,23]. In the latest (2018) round of the Work Environment and Health study in Denmark, 46% of healthcare workers reported having musculoskeletal pain several times per week, consequently representing the job group with the highest prevalence of weekly bodily pain [24]. In addition, 9% of the healthcare workers felt limited during work due to pain [24]. The high prevalence of musculoskeletal pain among healthcare workers may represent an even greater challenge in the future due to the demographic changes in most European countries with an increased proportion of older residents and thereby increased need for eldercare, potentially resulting in societies becoming short of healthcare workers [25].

The high prevalence of pain among healthcare workers may be explained by the high mental and physical demands they are confronted with in their daily work, comprising lifting and manually assisting persons – oftentimes with sustained and awkward postures [17, 18]. For instance, high physical exertion during eldercare work increased the odds of persistent low-back and knee pain (> 30 days during the past year) at 1-year follow-up [18], while heavy physical work and strenuous work postures increased the risk of disability pension among healthcare workers (including nurses) [21,22,23]. Additionally, musculoskeletal pain may also origin from chronic diseases such as osteoarthritis and cancer [26, 27]. The prevalence of sickness absence among nurses’ aides gradually increased during the 104 weeks before start of disability pension in a 15-year register follow-up cohort study [23]. These findings indicate that healthcare work is not only costly for the society and workplaces due to an increased risk of disability pension, but also due to a gradually increasing prevalence of sickness absence for at least 2 years before ending on disability pension [23]. This underlines the importance of addressing risk factors in the working environment that may predispose healthcare workers for ill health and hence push them out of the labour market prematurely. Since risk factors varies across job groups and the debilitating effect of the risk factors depends on the physical demands during work [28, 29], investigating risk factors in specific job groups provide valuable job-specific knowledge that can help to target suitable initiatives to reduce debilitating risk factors. Furthermore, both longer duration of pain [20] and pain intensity [9] in different body regions can have different consequences in relation to sickness absence among healthcare workers in eldercare (from now on called “eldercare workers”). In addition, work ability (proxy for disability pension) among nurses declined with higher intensity of musculoskeletal pain [30], while pain intensity in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and legs associated with increased work limitation (also a proxy for disability pension) in a dose-response manner among workers ≥50 years from the general working population [28, 29, 31]. Thus, while pain intensity is associated with poorer ability to work [28,29,30,31], and physical work demands and musculoskeletal pain (single- and multi-site pain) increase the risk of disability pension [15, 16, 21,22,23], no studies to date have investigated the dose-response association between pain intensity in different body regions and risk of disability pension among eldercare workers.

Thus, the aim of the present study was to investigate whether a dose-response association exists between pain intensity in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees, and disability pension among Danish eldercare workers. We hypothesized that higher pain intensity in all body regions is associated with higher risk of disability pension in a dose-response manner.

Methods

Study design and population

The present study is a prospective cohort study among eldercare workers with 11-year register follow-up using the Danish Register for Evaluation of Marginalization (DREAM); a national register on social transfer payments [32]. Questionnaires were sent to 12,744 eldercare workers in Denmark between late 2004 and spring 2005, where 9949 (78%) responded the questionnaire [22]. The present study excluded all male workers (N = 234) and workers who did not directly engage in care services (N = 1021, some of these were males). Thus, this study included 8731 (69%) female eldercare workers. Eldercare workers comprised social and healthcare assistants and helpers, other care helpers with no or short-term education, and nurses or therapists [22]. Because all participants did not reply to all questions, the number of participants for each analysis varies. The reporting of the study follows the STROBE recommendations [33].

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to the Danish legislation, research questionnaire- and register-based studies do not need approval from neither ethical and scientific committees nor informed consent (https://www.nvk.dk/~/media/NVK/Dokumenter/Vejledning_Engelsk.pdf) [34]. The study was notified to and registered at The Danish Data Protection Agency. All data were de-identified and analysed anonymously.

Risk factors

Musculoskeletal pain

Participants rated their average musculoskeletal pain intensity during the last 3 months in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees on a 0–9 numeric rating scale (NRS), where 0 indicated ‘no pain’ and 9 indicated ‘worst imaginable pain’ [9]. The scale was horizontally oriented to illustrate a modified visual-analogue scale [9, 35]. In the questionnaire, the three body regions were illustrated on a drawing from the Nordic Questionnaire [36]. We collapsed the pain intensities into the intervals 0–2 (‘No or low pain’), 3–4 (‘Moderate pain’), 5–6 (‘High pain’) and 7–9 (‘Very high pain’) in the subsequent analyses.

Outcome variable

Disability pension

Disability pension rates were obtained from the DREAM register, which contains weekly information on granted disability benefits, sickness absence, employment, education etc. for Danish residents. The DREAM register and the inclusion requirements were recently described in detail [22]. In the present study, we defined ‘disability pension’ as receiving any form of disability benefits which require full or partial loss of work ability, i.e. sheltered jobs, flex jobs and variants hereof, and full disability pension comprising 13 categories of disability benefits payment in DREAM [22].

Confounders

The analyses were controlled for relevant confounders from the baseline questionnaire including age (years, continuous variable), body mass index (BMI) (kg/m2, continuous variable), smoking (dichotomous variable: ‘Yes’/‘No’), education (categorical variables: e.g. social and healthcare assistant, nurse, therapist, none), leisure-time physical activity (categorical: low, moderate, and high level), pain intensity in other body regions (numeric rating scale: 0–9), psychosocial work factors (continuous variable (0–100): emotional demands, influence at work, role conflicts, quality of leadership) from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire [37], and physical exertion at work (Hollmann Index scale 0–62, where 62 is highest exertion and 0 is lowest) [9, 15, 22].

Statistical analyses

We used the Cox proportional hazards model to estimate the hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) of the pain intensity variables for receiving disability pension during follow-up. The time unit used in the Cox models is weeks, as the register provides week-to-week information throughout the follow-up period. The follow-up was 11 years or until censoring, which comprises death, voluntary early retirement pension, state pension, or emigration. Potential registered disability benefit payment within the follow-up period were non-censored and referred to as event times [22]. Organizational unit to which each worker belonged was added as a clustering factor using the random statement. Estimation method was maximum likelihood and the PHREG procedure of SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used. Model 1 was adjusted for age and pain intensity of the three pain regions (mutually adjusted). Model 2 adjusted for the same factors as model 1 and additionally for education, smoking, BMI, leisure-time physical activity, psychosocial work factors (emotional demands, influence at work, role conflicts, quality of leadership), and physical exertion at work. We performed a trend test to investigate whether a dose-response association existed between pain intensity in different body regions and risk of disability pension. Additionally, we performed stratified analyses for eldercare workers ≤45 years and > 45 years. An alpha level of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Population attributable risks (PAR) were calculated based on the HRs and proportion exposed (Pe) from model 2: PAR = Pe(HRe-1)/(1 + Pe(HRe-1)). Pe included all the numbers of pain intensity above 2.

Results

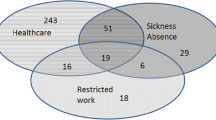

Participant characteristics are reported in Table 1. Mean age at baseline was 45.4 years, and 11.9% of the female eldercare workers received disability pension during the 11-year follow-up. The prevalence of moderate or more intense musculoskeletal pain in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees was 50.4, 54.0, and 23.9%, respectively (Table 2).

The baseline pain intensities as predictors for disability pension during the 11-year follow-up are provided in Table 2. Irrespective of pain region, a positive dose-response association was found between pain intensity and disability pension (trend test p < 0.001). For example, the fully adjusted model showed increased risk of disability pension, with HRs of 1.23 (95% CI 1.01–1.50), 1.60 (95% CI 1.31–1.96), and 2.34 (95% CI 1.88–2.92) for moderate, high, and very high pain intensity in the neck/shoulders, respectively. Furthermore, PARs for low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees were 15.5, 23.2, and 9.6%, respectively. Thus, if pain intensity in eldercare workers could be reduced to 2/9 or less, potentially 15.5, 23.2, and 9.6% fewer eldercare workers would have to receive disability pension.

Tables 3 and 4 provide pain intensities as predictors for future disability pension when stratified by age (≤45 years and > 45 years). The HRs and PARs for the eldercare workers ≤45 years were highest when having pain in neck/shoulders. PAR for pain in low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees among workers ≤45 years were 10.9, 27.6, and 9.3%, respectively (Table 3). For eldercare workers > 45 years, high and very high pain in all three body regions were predictors for future disability pension, while PAR was highest for low-back pain. PAR for pain in low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees were 19.7, 18.8, and 9.9%, respectively.

Discussion

The present study investigated musculoskeletal pain intensity as a risk factor for disability pension among female eldercare workers. To our best knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate a dose-response association between pain intensity in low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees, and future risk of disability pension among eldercare workers. Furthermore, the PAR analyses indicated that 15.5, 23.2, and 9.6% of disability pensions could be spared if pain intensities were reduced to ‘No or low pain’ (0–2 on 0–9 scale) in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees, respectively. When stratified by age, PAR was highest for pain in neck/shoulders among workers ≤45 years (27.6%), while PAR was highest for pain in low-back among workers > 45 years (19.7%).

The highly significant dose-response association (p < 0.001) and the high PAR documented in this study confirm the large consequences of musculoskeletal pain among eldercare workers. Musculoskeletal pain was not only highly prevalent at baseline (i.e. 50.4, 54.0, and 23.9% having at least moderate pain in low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees, respectively), it was also associated with a more than two-fold increased risk of leaving the labour market prematurely within 11 years of follow-up. Having moderate pain intensity or higher in the neck/shoulders and knees significantly increased the risk of disability pension among all eldercare workers, whereas a significantly increased risk of disability pension was only evident in individuals reporting high (5–6/9) or very high (7–9/9) low-back pain. These findings are somewhat in agreement with a previous study that found a higher pain intensity threshold for the low-back (5/9) associated with an increased risk of long-term sickness absence than the corresponding thresholds for pain in neck/shoulders and knees (4 and 3, respectively) at 1-year follow-up among the same group of workers as the present study [9]. These findings could indicate that moderate pain in the low-back is more tolerable and less debilitating among eldercare workers than pain in neck/shoulders and knees, which may be explained by differences in physical work demands between the investigated muscle groups. Thus, low-back muscles may serve a more postural role during healthcare work while neck/shoulders and knees have a more active role during the work tasks, e.g. during lifting/assisting and walking. Another rationale may be that many suffer from non-specific low-back pain that subsides and recurs during their lifetime [38] whereas pain in neck/shoulders and knees to a larger extent may originate from osteoarthritis or other degenerative chronic musculoskeletal disorders, which tend to progress negatively with age [26]. Contrastingly, our age-stratified analyses show highest PAR for pain in low-back in the older workers (> 45 years) and highest PAR for neck/shoulder pain in the younger workers (≤45 years). However, the PAR for pain in neck/shoulders is approximately at the same level for the older workers, whereas PAR for low-back pain and knee pain are markedly higher among the older eldercare workers compared to their younger counterparts. This corresponds with recent findings that pain progresses with age [26] and that high physical exertions have worse consequences for older workers [39]. Another argument for the somewhat contrasting findings is the lower statistical power in the age-stratified analyses. The wider 95% CIs in these analyses indicate that the age-stratified results should be interpreted with some caution.

Numerous studies have found pain in different body regions, e.g. low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees, to be debilitating among various job groups including healthcare workers [8,9,10]. Both longer duration [20] and higher intensity [9] of pain in the low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees increases the risk of long-term sickness absence, where a dose-response association was observed for all body regions [9]. Furthermore, both single- and multisite pain predict future disability pension in different job groups, with higher number of pain regions leading to increased risk of disability pension [15, 16, 40]. The present study investigated specific pain regions that were mutually adjusted and found strong associations to disability pension in workers with pain in all investigated body regions. Including that higher pain intensity in low-back, neck/shoulders, and legs associate with lower work ability [28, 29, 31], all these findings underscore the importance of targeted focus on reducing the pain prevalence and more specifically pain intensity among eldercare workers to retain good health and hence prolong the working life. Furthermore, because of the high prevalence of pain and disability pension among eldercare workers, eldercare workers should be considered in suitable pension reforms if they are not capable of working until the statutory pension age.

The present study’s findings that musculoskeletal pain intensity in different body regions function as a predictor for future disability pension among eldercare workers supplements previous findings that high physical work demands [21, 22], pain duration [23], and multi-site pain [15] predict disability pension. As a novel finding, the present study found high/very high pain intensity to predict disability pension among both younger and older workers. Additionally, higher physical work demands and musculoskeletal pain intensity in the low-back [28], neck/shoulders [31], and legs [29] associated with lower work ability compared to workers with the same pain intensity but less physically demanding work, i.e. workers with physically demanding occupations are more affected by their pain. Since eldercare work is physically demanding, and work ability function as a proxy for disability pension, our findings elaborate on these findings that pain intensity may have a debilitating effect on work ability and consequently leads to early retirement for workers with physically demanding occupations. The sample of the present study included only those directly involved in care work, and the sample is large and spread across the country. Thus, it is reasonable to assume that the sample is representative for eldercare workers in Denmark. ‘Human health and social work activities’ in Denmark is fairly close to the average EU-27 for many work-related factors [41]. Thus, the generalizability of the present findings may also, although with certain caution, be extended to the European countries as a whole. However, the present study do not have information on the diagnosis for disability pension, meaning that we cannot conclude that the disability pensions are due to musculoskeletal pain. The study show that more intense musculoskeletal pain is associated with higher risk of disability pension within 11 years of follow-up.

The PAR analyses indicate a potential in saving people from leaving the labour market prematurely. Workplace- and societal initiatives could prolong the working life for many workers and should be prioritized to improve the organisation and physical work environment of eldercare work. For example, the use of technical assistive devices for patients transfer is associated with reduced physical workload and significantly decreases the risk for back injury and low-back pain [42, 43], whereas a lack of assistive devices and ability to use the devices is a common contributing factor for back injury events among eldercare workers [44, 45]. Another relevant initiative to prevent and reduce pain is physical exercise at the workplace, particularly strength training, which also improves the physical capacity through increased muscle strength and muscular endurance among workers with physically demanding occupations [46, 47], whereby the work tasks, e.g. lifting and assisting people, are performed at a lower relative strain. In fact, low physical capacity function as an increased risk factor for future disability pension [48]. Thus, a higher physical capacity through physical exercise could potentially prolong the working life since workers with less physically demanding occupations retire later than workers with hard physical work [4]. Furthermore, an improved physical capacity will benefit the workers during the inherent age-related loss in muscle mass and strength with aging (sarcopenia) [49,50,51] and postpone the point when reaching the “disability threshold” where the workers are unable to meet their physical work demands [49, 50]. Another initiative to reduce the pain intensity among eldercare workers, and thereby potentially prolong their working life, could be to adjust the work tasks to the worker’s physical capacity. Adjusting the work tasks would reduce the physical strain, which may increase the work ability and reduce the risk of leaving the labour market temporarily or permanently. Lastly, reallocating eldercare workers with a high level of musculoskeletal pain to other job functions with less physical demands may also be a suitable solution to lower the pain and reduce the risk of disability pension.

Limitations and strengths

The present study contains some methodological limitations and strengths. The homogenous group of female eldercare workers in eldercare implies that the findings only apply to the included population of female eldercare workers and cannot be generalized to the general working population. However, the inclusion of this homogenous group reduces the risk of socioeconomic confounding. A further limitation of the study may be that our data only pertains to currently employed eldercare workers and do not contain information on lifetime work exposures (preceding or succeeding eldercare work) that potentially may influence the risk of disability pension. Moreover, the present results may be caused by other underlying factors such as poor health or chronic diseases. However, excluding those with poor health and chronic conditions at baseline also leads to excluding many workers with pain. Therefore, such an approach would create a selected group of completely “healthy” respondents where some would still report high pain of unknown cause, i.e. maybe not being completely healthy (unidentified chronic disease). Thus, as the cause of pain in many cases is unknown, we chose to include all workers – in spite of known or unknown chronic disease - and use pain intensity as the predictor variable. A strength of the study is the use of the high-quality DREAM to register disability pension during an 11-year period. In addition, investigating the risk of disability pension from pain intensity in various body regions (low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees) strengthens the study and increases the specificity of the study in order to improve the physical working environment among eldercare workers. At last, the calculation of PAR is a strength as it increases our understanding of the consequences of work-related musculoskeletal pain.

Conclusions

The present study demonstrates a positive dose-response association between pain intensity in low-back, neck/shoulders, and knees, and risk of disability pension among female eldercare workers. Reducing pain levels among eldercare workers can reduce the risk of future disability pension and prevent that a substantial proportion of eldercare workers are pushed out of the labour market prematurely. Improving the physical working environment, reorganising work tasks, and promoting a healthy lifestyle can help to reduce high prevalence and intensity of pain among eldercare workers, and ultimately ensure a long and healthy working life.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon reasonable request. The authors encourage collaboration and use of the data by other researchers. Data are stored on the server of Statistics Denmark, and researchers interested in using the data for scientific purposes should contact the project leader Prof. Lars L. Andersen, lla@nfa.dk.

Abbreviations

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- DREAM:

-

Danish Register for Evaluation of Marginalization

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- PAR:

-

Population attributable risk

- NRS:

-

Numeric rating scale

References

Safiri S, Kolahi AA, Cross M, Carson-Chahhoud K, Almasi-Hashiani A, Kaufman J, et al. Global, regional, and national burden of other musculoskeletal disorders 1990–2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;60:855.

da Costa BR, Vieira ER. Risk factors for work-related musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review of recent longitudinal studies. Am J Ind Med. 2010;53(3):285–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajim.20750.

Øverås CK, Villumsen M, Axén I, Cabrita M, Leboeuf-Yde C, Hartvigsen J, et al. Association between objectively measured physical behaviour and neck- and/or low back pain: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2020;24(6):1007–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.1551.

Sundstrup E, Hansen ÅM, Mortensen EL, Poulsen OM, Clausen T, Rugulies R, et al. Retrospectively assessed physical work environment during working life and risk of sickness absence and labour market exit among older workers. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(2):114–23. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2016-104279.

Pedersen J, Schultz BB, Madsen IEH, Solovieva S, Andersen LL. High physical work demands and working life expectancy in Denmark. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(8):576–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2019-106359.

d’Errico A, Burr H, Pattloch D, Kersten N, Rose U. Working conditions as risk factors for early exit from work-in a cohort of 2351 employees in Germany. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020;15.

Miranda H, Kaila-Kangas L, Heliövaara M, Leino-Arjas P, Haukka E, Liira J, et al. Musculoskeletal pain at multiple sites and its effects on work ability in a general working population. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(7):449–55. https://doi.org/10.1136/oem.2009.048249.

Ezzatvar Y, Calatayud J, Andersen LL, Vinstrup J, Alarcón J, Casaña J. Dose-response association between multi-site musculoskeletal pain and work ability in physical therapists: a cross-sectional study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020;93(7):863–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-020-01533-6.

Andersen LL, Clausen T, Burr H, Holtermann A. Threshold of musculoskeletal pain intensity for increased risk of long-term sickness absence among female healthcare workers in eldercare. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e41287. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0041287.

Coggon D, Ntani G, Walker-Bone K, Felli VE, Harari R, Barrero LH, et al. Associations of sickness absence for pain in the low back, neck and shoulders with wider propensity to pain. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(5):301–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2019-106193.

Jansson C, Alexanderson K. Sickness absence due to musculoskeletal diagnoses and risk of diagnosis-specific disability pension: a nationwide Swedish prospective cohort study. Pain. 2013;154(6):933–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pain.2013.03.001.

Jääskeläinen A, Kausto J, Seitsamo J, Ojajärvi A, Nygård C-H, Arjas E, et al. Work ability index and perceived work ability as predictors of disability pension: a prospective study among Finnish municipal employees. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42(6):490–9. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3598.

Kinnunen U, Nätti J. Work ability score and future work ability as predictors of register-based disability pension and long-term sickness absence: a three-year follow-up study. Scand J Public Health. 2018;46(3):321–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494817745190.

Salonen L, Blomgren J, Laaksonen M. From long-term sickness absence to disability retirement: diagnostic and occupational class differences within the working-age Finnish population. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1078. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09158-7.

Ropponen A, Narusyte J, Mittendorfer-Rutz E, Svedberg P. Number of pain locations as a predictor of cause-specific disability pension in Sweden-do common mental disorders play a role? J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61(8):646–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001635.

Lallukka T, Hiilamo A, Oakman J, Mänty M, Pietiläinen O, Rahkonen O, et al. Recurrent pain and work disability: a record linkage study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2020;93(4):421–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-019-01494-5.

Robstad Andersen G, Westgaard RH. Perceived occupational exposures of home care workers and the association to general tension, shoulder-neck and low back pain. Work. 2014;49(4):723–33. https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-131710.

Andersen LL, Clausen T, Persson R, Holtermann A. Perceived physical exertion during healthcare work and risk of chronic pain in different body regions: prospective cohort study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2013 Aug;86(6):681–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-012-0808-y.

Diana Nørregaard Rasmussen C, Karstad K, Søgaard K, Rugulies R, Burdorf A, Holtermann A. Patterns in the Occurrence and Duration of Musculoskeletal Pain and Interference with Work among Eldercare Workers-A One-Year Longitudinal Study with Measurements Every Four Weeks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(16):2990.

Andersen LL, Clausen T, Mortensen OS, Burr H, Holtermann A. A prospective cohort study on musculoskeletal risk factors for long-term sickness absence among healthcare workers in eldercare. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85(6):615–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00420-011-0709-5.

Gustafsson K, Marklund S, Aronsson G, Leineweber C. Physical work environment factors affecting risk for disability pension due to mental or musculoskeletal diagnoses among nursing professionals, care assistants and other occupations: a prospective, population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(10):e026491.

Andersen LL, Villadsen E, Clausen T. Influence of physical and psychosocial working conditions for the risk of disability pension among healthy female eldercare workers: prospective cohort. Scand J Public Health. 2020;48(4):460–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494819831821.

Jensen LD, Ryom PK, Christensen MV, Andersen JH. Differences in risk factors for voluntary early retirement and disability pension: a 15-year follow-up in a cohort of nurses’ aides. BMJ Open. 2012;2(6):e000991.

NRCWE. Work Environment & Health in Denmark [Internet]. National Research Centre for the Working Environment (NRCWE); 2018 [cited 2020 Oct 29]. Available from: https://at.dk/arbejdsmiljoe-i-tal/analyser-og-publikationer/arbejdsmiljoe-og-helbred-2012-2018/

Ilmarinen J. The ageing workforce--challenges for occupational health. Occup Med (Lond). 2006 Sep;56(6):362–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kql046.

Culvenor AG, Øiestad BE, Hart HF, Stefanik JJ, Guermazi A, Crossley KM. Prevalence of knee osteoarthritis features on magnetic resonance imaging in asymptomatic uninjured adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Sports Med. 2019 Oct;53(20):1268–78. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2018-099257.

Fenlon D, Addington-Hall JM, O’Callaghan AC, Clough J, Nicholls P, Simmonds P. A survey of joint and muscle aches, pain, and stiffness comparing women with and without breast cancer. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2013 Oct;46(4):523–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.10.282.

Nygaard PP, Skovlund SV, Sundstrup E, Andersen LL. Is low-back pain a limiting factor for senior workers with high physical work demands? A cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020 Sep 21;21(1):622. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03643-1.

Skovlund SV, Bláfoss R, Sundstrup E, Thomassen K, Andersen LL. Joint association of physical work demands and leg pain intensity for work limitations due to pain in senior workers: cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2020 Nov 18;20(1):1741. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09860-6.

Magnago TS, Lima AC, Prochnow A, Ceron MD, Tavares JP, Urbanetto JD. Intensity of musculoskeletal pain and (in) ability to work in nursing. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. 2012 Dec;20(6):1125–33. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692012000600015.

Bayattork M, Skovlund SV, Sundstrup E, Andersen LL. Work limitations due to neck-shoulder pain and physical work demands in older workers: cross-sectional study. Int Arch Occup Environ Health 2020 26;

Hjollund NH, Larsen FB, Andersen JH. Register-based follow-up of social benefits and other transfer payments: accuracy and degree of completeness in a Danish interdepartmental administrative database compared with a population-based survey. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(5):497–502. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940701271882.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008 Apr;61(4):344–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008.

Committee System on Biomedical Research Ethics. Guidelines about Notification etc. of a Biomedical Research Project to the Committee System on Biomedical Research Ethics [Internet]. 2011. Available from: https://www.nvk.dk/~/media/NVK/Dokumenter/Vejledning_Engelsk.pdf

Pincus T, Bergman M, Sokka T, Roth J, Swearingen C, Yazici Y. Visual analog scales in formats other than a 10 centimeter horizontal line to assess pain and other clinical data. J Rheumatol. 2008;35(8):1550–8.

Kuorinka I, Jonsson B, Kilbom A, Vinterberg H, Biering-Sørensen F, Andersson G, et al. Standardised Nordic questionnaires for the analysis of musculoskeletal symptoms. Appl Ergon. 1987 Sep;18(3):233–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/0003-6870(87)90010-X.

Pejtersen JH, Kristensen TS, Borg V, Bjorner JB. The second version of the Copenhagen psychosocial questionnaire. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(3 Suppl):8–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494809349858.

Hartvigsen J, Hancock MJ, Kongsted A, Louw Q, Ferreira ML, Genevay S, et al. What low back pain is and why we need to pay attention. Lancet. 2018;391(10137):2356–67.

Andersen LL, Pedersen J, Sundstrup E, Thorsen SV, Rugulies R. High physical work demands have worse consequences for older workers: prospective study of long-term sickness absence among 69 117 employees. Occup Environ Med. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2020-107281.

Sommer TG, Svendsen SW, Frost P. Sickness absence and permanent work disability in relation to upper- and lower-body pain and occupational mechanical and psychosocial exposures. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42(6):481–9.

European Agency for Safety and Health at Work. Human health and social work activities [Internet]. How European workplaces manage safety and health. [cited 2021 May 21]. Available from: https://visualisation.osha.europa.eu/esener#!/en/survey/detailpage-european-bar-chart/2019/osh-management/en_1/E3Q200_1/activity-sector/20/11

Andersen LL, Burdorf A, Fallentin N, Persson R, Jakobsen MD, Mortensen OS, et al. Patient transfers and assistive devices: prospective cohort study on the risk for occupational back injury among healthcare workers. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2014;40(1):74–81. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3382.

Vinstrup J, Jakobsen MD, Madeleine P, Andersen LL. Physical exposure during patient transfer and risk of back injury & low-back pain: prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):715. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03731-2.

Andersen LL, Vinstrup J, Villadsen E, Jay K, Jakobsen MD. Physical and psychosocial work environmental risk factors for Back injury among healthcare workers: prospective cohort study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;15:16(22).

Jakobsen MD, Aust B, Kines P, Madeleine P, Andersen LL. Participatory organizational intervention for improved use of assistive devices in patient transfer: a single-blinded cluster randomized controlled trial. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019;45(2):146–57.

Sundstrup E, Seeberg KGV, Bengtsen E, Andersen LL. A systematic review of workplace interventions to rehabilitate musculoskeletal disorders among employees with physical demanding work. J Occup Rehabil. 2020;30(4):588–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-020-09879-x.

Sundstrup E, Jakobsen MD, Brandt M, Jay K, Aagaard P, Andersen LL. Strength training improves fatigue resistance and self-rated health in workers with chronic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:4137918.

Sundstrup E, Hansen ÅM, Mortensen EL, Poulsen OM, Clausen T, Rugulies R, et al. Physical capability in midlife and risk of disability pension and long-term sickness absence: prospective cohort study with register follow-up. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2019;45(6):610–21. https://doi.org/10.5271/sjweh.3842.

Skelton DA, Mavroeidi A. How do muscle and bone strengthening and balance activities (MBSBA) vary across the life course, and are there particular ages where MBSBA are most important? J Frailty Sarcopenia Falls. 2018;3(2):74–84. https://doi.org/10.22540/JFSF-03-074.

Peeters G, Dobson AJ, Deeg DJH, Brown WJ. A life-course perspective on physical functioning in women. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91(9):661–70. https://doi.org/10.2471/BLT.13.123075.

Walston JD. Sarcopenia in older adults. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24(6):623–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0b013e328358d59b.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the co-workers from the Danish Health Care Worker Cohort (DHCWC) 2004 study group for their contribution to the data collection.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from the Danish Parliament (SATS-pulje). The funder had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LLA designed the present study aim and performed the analyses. RB wrote the draft before JV, SVS, RLB, JC, TC and LLA critically read and reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

According to the Danish legislation, research questionnaire- and register-based studies do not need approval from neither ethical and scientific committees nor informed consent. The study was notified to and registered at The Danish Data Protection Agency. All data were de-identified and analysed anonymously.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declared that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bláfoss, R., Vinstrup, J., Skovlund, S.V. et al. Musculoskeletal pain intensity in different body regions and risk of disability pension among female eldercare workers: prospective cohort study with 11-year register follow-up. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 22, 771 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04655-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-021-04655-1