Abstract

Background

Anterior cervical spine surgery is often associated with postoperative dysphagia, but chronic dysphagia caused by laryngo-vertebral synostosis is extremely rare. We report a case of chronic dysphagia caused by synostosis between the cricoid cartilage and cervical spine after anterior surgery for cervical spine trauma.

Case presentations

We present a case of a 39-year-old man who had sustained complex spine trauma at C5–6 associated with complete spinal cord injury at the age of 22; the patient presented with a 5-year history of chronic dysphagia. Computed tomography demonstrated posterior shift of the esophagus as well as calcification of the cricoid cartilage and its fusion to the right anterior tubercle of the C5 vertebra. A barium swallow study demonstrated significant barium aspiration into the airway and no laryngeal elevation. The patient underwent resection of the bony bridge and omohyoid muscle flap insertion. His symptoms ameliorated after surgery.

Conclusion

Synostosis between the cricoid cartilage and cervical spine may occur associated with cervical spine trauma and causes chronic dysphagia. Resection of the fused part can improve dysphagia caused by this rare condition and omohyoid muscle flap might be a good option to prevent recurrence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Anterior cervical spine surgery is often associated with postoperative dysphagia [1]. Most patients with dysphagia improve over time, but a significant proportion have persistent symptoms, with the incidence of chronic dysphagia reported to be 12.5–35% [2,3,4]. Previous reports suggest that adhesion and protrusion of instrumentation or grafts could potentially cause chronic postoperative dysphagia; however, synostosis of the laryngeal cartilages and cervical spine is extremely rare. We report a case of chronic dysphagia caused by synostosis between the cricoid cartilage and cervical spine after anterior surgery for cervical spine trauma.

Case presentation

A 39-year-old East Asian man visited our hospital with a 5-year history of progressive dysphagia. At the age of 22, the patient had sustained C5–6 complex fracture/dislocation and complete cervical spinal cord injury at the C7 level due to a motor vehicle accident. No intracranial injury had been recorded. A halo traction was applied on the first day of his hospitalization as a temporary fixation, but definitive treatment was delayed due to severe respiratory distress, which required mechanical ventilation. He underwent anterior C5–6 corpectomy and fusion with iliac crest bone autograft without instrumentation 23 days after the admission. No bone morphologic protein was used. During the initial hospital stay, he underwent tracheostomy because of prolonged respiratory distress due to associated injuries. The tracheostomy site was complicated with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, which was treated with antibiotics and repeated debridement. Since the time of injury, total non-oral nutrition had been continued for over 3 months, because of frequent aspiration and pain during swallowing due to inflammation of the tracheostomy site. No barium swallowing test was performed during the initial hospitalization. After swallowing rehabilitation, the patient could swallow liquid and solid food without aspiration. However, 12 years later, his dysphagia relapsed and gradually progressed. At the time of his 17-year visit, the patient aspirated frequently when he swallowed liquids or solids, to the extent that self-suctioning from the previous tracheostomy site was frequently required.

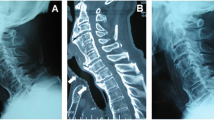

Computed tomography (CT) scans of the cervical spine revealed almost complete resorption of the bone graft and a posterior shifted esophagus. The injured spinal columns were fused via the posterior and remaining anterior parts of the vertebrae. A bony bridge of heterotopic ossification was observed between the right posterior part of the cricoid cartilage and the right anterior tubercle of the C5 vertebra (Fig. 1). A barium swallow study demonstrated significant barium aspiration into the airway and no laryngeal elevation (Fig. 2) (see Video, Supplemental Digital Content 1).

Computed tomography (CT) images at initial examination: a An axial image at C5 level showing synostosis between the right posterior part of the cricoid cartilage and the right anterior tubercle of C5 (arrow); total absorption of grafted bone was observed and the esophagus shifted markedly to the posterior side (arrowhead). b sagittal reconstruction of the CT showing the posteriorly shifted cricoid cartilage (arrow) and esophagus (arrowhead)

The patient underwent resection of the synostosis; the standard Smith-Peterson approach was utilized through the previous surgical scar. The resection was performed using a high-speed bar and small chisels. The ipsilateral omohyoid muscle (OM) was detached from the hyoid cartilage and the flap was inserted between the vertebral bone and cricoid cartilage to prevent recurrence. A laryngeal suspension procedure [5] was added by otorhinolaryngologists. After surgery, his dysphagia resolved and he could swallow liquid and solids without aspiration. A follow-up barium swallow on the 10th postoperative day demonstrated improved laryngeal elevation and no aspiration (Fig. 3) (see Video, Supplemental Digital Content 2). The patient has had no dysphagia or recurrence 5 years after the surgery.

Postoperative barium swallow study on the 10th postoperative day: a image of early pharyngeal phase showing interval between the cricoid cartilage and spine (double-headed arrow) (C3/4 anterior osteophyte was also removed). Solid line indicating height of top of the cricoid cartilage. b image of late pharyngeal-early esophageal phase showing no aspiration (arrowhead) and improved elevation of the larynges (solid line: top of the cricoid cartilage, dotted line: previous position of top of the cricoid cartilage)

Discussion

Laryngeal cartilages are often ossified. Among men, over 35% of thyroid and 20% of cricoid cartilages are ossified [6], but synostoses between laryngeal bony/cartilaginous structures and vertebrae were extremely rare. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of postoperative synostosis between the cricoid cartilage and cervical spine.

Among the published literature, we found only two cases of synostosis between the other laryngeal cartilaginous structure, thyroid cartilage, and vertebrae. Han et al. reported a case of synostosis between the thyroid cartilage and C5–7 [7]; their patient showed arrested laryngeal elevation, leading to severe dysphagia like our case. Moses et al. reported a case of posttraumatic synostosis between the thyroid cartilage and C3 [8]. Both cases had cervical spine fractures that were treated conservatively. (7, 8) The summary of previously reported cases is provided in Table 1.

The pathogenesis of laryngo-spinal synostosis is unclear. In Han’s report, the authors mentioned that small bony fragments were dispersed between the thyroid cartilage and vertebral bones on initial CT; they suggested these fragments might have formed a bony bridge [7]. Posttraumatic synostosis between two neighboring bones has been investigated mainly in the forearm and ankle [9, 10]. The risk factors for posttraumatic synostosis are classified into two main categories: trauma-related and treatment-related [10, 11]. A significant proportion of these risk factors are associated with systemic or local inflammation, which overlap with the general risk factors for posttraumatic heterotopic ossification (HO) (Table 2) [12,13,14]. Previous studies demonstrated that various inflammatory cytokines were increased in the blood and local tissue among patients with severe HO [15, 16]. In this case, infection around the tracheostomy site and almost total resorption of the grafted bone was observed. According to patient history, it is highly likely that the anterior cervical fusion surgical site was also infected. Another possibility is that the patient might have had an esophageal injury due to the spinal injury itself or ACF, although it was not mentioned in the previous hospitalization record and no workup for esophageal injury was performed. The presence of local inflammation due to surgical site infection or esophageal injury might have contributed to the incidence of cricoid-vertebral synostosis in our case. Moreover, our patient showed almost complete resorption of the grafted bone for possibly associated infection and a posterior shifted esophagus. This anatomical change pushed the laryngeal cartilages closer to the vertebra and might have contributed to synostosis formation, along with other factors mentioned earlier. Lastly, non-oral nutrition had continued for over 3 months in this case. This prolonged immobility of the larynx was one possible reason of synostosis. One interesting difference between laryngo-vertebral synostosis and radioulnar synostosis (tibiofibular synostosis usually does not show any symptoms [9]) were the intervals between the initial injury and synostosis symptom onset. Among patients with laryngo-vertebral synostosis, the intervals between the initial injury and onset of dysphagia were 20 months in Moses’s report [8], over 6 years in Han’s case [7], and 12 years in our case, whereas radioulnar synostosis cases showed earlier symptom onset, typically less than 12 months [10, 17, 18]. This might suggest that laryngo-vertebral synostosis demonstrates more gradual development of bridging bone than synostosis of the forearm, or there might be compensating mechanisms of laryngeal movement, which prevent the synostosis from becoming symptomatic.

Laryngo-vertebral synostosis likely impairs the dynamic coordinated movement of swallowing. In our case, synostosis resection yielded an excellent result; the follow-up barium swallow study demonstrated improved laryngeal elevation. Han et al. mentioned that laryngeal elevation improved after synostosis resection. Moses et al. treated their patient conservatively, but the reduced laryngeal elevation and delay in the pharyngeal swallowing phase persisted. For severe dysphagia, we believe that synostosis removal should be considered to ameliorate symptoms.

We used the OM flap as an interposition for preventing recurrence. For synostosis in the forearm, although the supporting evidence is limited, various materials are used for preventing recurrence [11]. Those include bone wax, artificial material sheets (silicon or Gore-Tex®), free or pediculed fat flap, and fascia. The OM flap was used for esophageal or pharyngeal perforation associated with anterior cervical spine surgery [19]. Surek et al. reported two cases of esophageal perforation treated with a superior OM flap; the flap can be easily mobilized during neck exploration and the omohyoid is thin, well-vascularized, and of adequate length to reach the mid-to-lower cervical spine [19]. An OM flap might be a good option for interposition after laryngo-vertebral synostosis resection.

Availability of data and materials

Data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ACF:

-

Anterior cervical fusion

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- HO:

-

Heterotopic ossification

- MRSA:

-

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- OM:

-

Omohyoid muscle

References

Joaquim AF, Murar J, Savage JW, Patel AA. Dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a systematic review of potential preventative measures. Spine J. 2014;14:2246–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spinee.2014.03.030.

Yue WM, Brodner W, Highland TR. Persistent swallowing and voice problems after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion with allograft and plating: a 5- to 11-year follow-up study. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:677–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00586-004-0849-3.

Bazaz R, Lee MJ, Yoo JU. Incidence of dysphagia after anterior cervical spine surgery: a prospective study. Spine. 2002;27:2453–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.brs.0000031407.52778.4b.

Winslow CP, Winslow TJ, Wax MK. Dysphonia and dysphagia following the anterior approach to the cervical spine. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127:51–5.

Goode RL. Laryngeal suspension in head and neck surgery. Laryngoscope. 1976;86:349–55. https://doi.org/10.1288/00005537-197603000-00004.

Mupparapu M, Vuppalapati A. Ossification of laryngeal cartilages on lateral cephalometric radiographs. Angle Orthodontist. 2005;75:196–201. https://doi.org/10.1043/0003-3219(2005)075<0192:OOLCOL>2.0.CO;2.

Han IH, Choi BK, Wang SG, Lee JC. Posttraumatic synostosis between the thyroid cartilage and the cervical spine causing dysphagia. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33:358–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2011.08.004.

Moses RL, Cavalli GI, Schmidt RJ, Rao VM, Cotler J, Cohn J, Spiegel JR. Posttraumatic synostosis of the cervical spine to the thyroid cartilage presenting as dysphagia. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:S84–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0194-59989770065-2.

Hinds RM, Lazaro LE, Burket JC, Lorich DG. Risk factors for posttraumatic synostosis and outcomes following operative treatment of ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int. 2014;35:141–7. https://doi.org/10.1177/1071100713510913.

Vince KG, Miller JE. Cross-union complicating fracture of the forearm. Part I: Adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am Vol. 1987;69:640–53.

Dohn P, Khiami F, Rolland E, Goubier JN. Adult post-traumatic radioulnar synostosis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2012;98:709–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.otsr.2012.04.018.

Barfield WR, Holmes RE, Hartsock LA. Heterotopic ossification in trauma. Orthop Clin North Am. 2017;48:35–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocl.2016.08.009.

Meyers C, Lisiecki J, Miller S, Levin A, Fayad L, Ding C, Sono T, McCarthy E, Levi B, James AW. Heterotopic ossification: a comprehensive review. JBMR Plus. 2019;3:e10172. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbm4.10172.

Slone HS, Walton ZJ, Daly CA, Chapin RW, Barfield WR, Leddy LR, Hartsock LA. The impact of race on the development of severe heterotopic ossification following acetabular fracture surgery. Injury. 2015;46:1069–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2015.01.039.

Forsberg JA, Potter BK, Polfer EM, Safford SD, Elster EA. Do inflammatory markers portend heterotopic ossification and wound failure in combat wounds? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2845–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-014-3694-7.

Forsberg JA, Pepek JM, Wagner S, Wilson K, Flint J, Andersen RC, Tadaki D, Gage FA, Stojadinovic A, Elster EA. Heterotopic ossification in high-energy wartime extremity injuries: prevalence and risk factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91:1084–91. https://doi.org/10.2106/jbjs.%20H.00792.

Failla J, Amadio PC, Morrey B. Post-traumatic proximal radio-ulnar synostosis. Results of surgical treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:1208–13.

Bauer G, Arand M, Mutschler W. Post-traumatic radioulnar synostosis after forearm fracture osteosynthesis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;110:142–5.

Surek CC, Girod DA. Superior omohyoid muscle flap repair of cervical esophageal perforation induced by spinal hardware. Ear Nose Throat J. 2014;93:E38–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/014556131409301203.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Kazunori Sato as well as the other staff in the Department of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, Ohta-Nishinouchi Hospital for their help with clinical evaluation and collaboration in surgical care of the patient.

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

IO conceptualized, collected and interpreted the clinical data, and wrote the manuscript. JO, YH, and YU collected and interpreted the clinical data, and revised the manuscript critically for important content. TT and KI revised the manuscript critically for important content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient. A statement of the ethics committee was not required for this anonymized case report in accordance with the legislation of the Institutional Review Committee of Ohta-Nishinouchi Hospital.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Supplemental Video Content 1. Preoperative barium swallow study

Additional file 2.

Supplemental Video Content 2. Follow-up barium swallow study on the 10th postoperative

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Okano, I., Omata, J., Hoshino, Y. et al. Chronic dysphagia caused by Laryngo-vertebral Synostosis after anterior fusion for cervical spine trauma: a case report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21, 143 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-3152-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-3152-5