Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to explore the feasibility of using a non-absorbable biocompatible polyester patch to augment open repair of massive rotator cuff tears (Patch group) and compare outcomes with other treatment options (Non-patch group).

Methods

Participants referred to orthopaedic clinics for rotator cuff surgery were recruited. Choice of intervention (Patch or Non-patch) was based on patient preference and intra-operative findings. Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS), Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), and Constant score were completed at baseline and 6 months. Shoulder MRI was performed at baseline and 6 months to assess fat fraction and Goutallier classification pre- and post- treatment. Feasibility outcomes (including retention, consent and missing data) were assessed.

Results

Sixty-eight participants (29 in the Patch group, 39 in Non-patch group) were included (mean age 65.3 years). Conversion to consent (92.6%), missing data (0% at baseline), and attrition rate (16%) were deemed successful feasibility endpoints. There was significant improvement in the Patch group compared to Non-patch at 6 months in OSS (difference in medians 9.76 (95% CI 2.25, 17.29) and SPADI: 22.97 (95% CI 3.02, 42.92), with no substantive differences in Constant score. The patch group had a higher proportion of participants improving greater than MCID for OSS (78% vs 62%) and SPADI (63% vs 50%) respectively. Analysis of the 48 paired MRIs demonstrated a slight increase in the fat fraction for supraspinatus (53 to 55%), and infraspinatus (26 to 29%) at 6 months. These differences were similar and in the same direction when the participants were analysed by treatment group. The Goutallier score remained the same or worsened one grade in both groups equally.

Conclusions

This study indicates that a definitive clinical trial investigating the use of a non-absorbable patch to augment repair of massive rotator cuff tears is feasible. In such patients, the patch has the potential to improve shoulder symptoms at 6 months.

Trial registration

ISRCTN, ISRCTN79844053, Registered 15th October 2014 (retrospectively registered).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the United Kingdom, 2.4% of all primary care consultations involve shoulder problems, and of these around 70% have rotator cuff pathology affecting their daily living [1, 2]. The prevalence of massive cuff tears ranges from 6.4–12% [3,4,5] with the management of symptomatic large and massive rotator cuff tears (RoCTs) presenting significant problems to the shoulder surgeon [6].

Repair of symptomatic RoCTs results in better clinical results compared to conservatively managed tears [7, 8]. Rates of re-rupture following repair vary significantly (7–46%) [9, 10] but for massive tears can be as high as 94% [8]. Commonly reported risk factors for failure are poor tendon quality, fatty atrophy, number of tendons involved, pre-operative tear size, tension on repair and patient age [11,12,13,14].

The management of large and massive RoCTs in shoulders with minimal arthritis remains a dilemma for shoulder surgeons [15, 16] . There are many options available, including specialised rehabilitation, simple arthroscopic surgery including debridement [17,18,19,20], long head of biceps tenotomy, bursectomy [21, 22], various tendon transfers [23, 24] through to formal repair of the tendon. This may be in the form of partial repair or complete repair where achievable. Current published outcomes for all these measures have been relatively successful, but re-tear rates are often high, and clinical outcomes can deteriorate after 2 years [25, 26]. This has therefore led to the development of further techniques, including use of patch to augment repair, subacromial spacer insertion and superior capsular reconstruction [27].

Surgeons have also investigated the use of patch grafts to bridge or augment larger tears in poor quality tendons with promising results [28,29,30]. However, these reports are predominantly case series with no attempt to compare the results with other, sometimes simpler, surgical options which may provide satisfactory outcomes [21, 31, 32]. The James Lind Alliance have also highlighted the need to examine different management options for repair of rotator cuff tears as a priority area of research [33].

We conducted a study to determine the feasibility of conducting a randomised controlled trial using patch-assisted surgery; and to compare the clinical outcomes and MRI findings of patients with massive RoCTs who were managed with patch-assisted surgery against patients managed with traditional options (non-surgical physiotherapy-based rehabilitation, arthroscopic repair, and arthroscopic debridement).

Methods

Design overview

The Shoulder Patch for Rotator Cuff (SPARC) study was a pragmatic, two-arm feasibility study. The study protocol was approved by Leeds West Research Ethics Committee (13/YH/0030) and registered on ISRCTN (ISRCTN79844053). Written informed consent was obtained for all participants prior to screening. Participants were recruited from 1st September 2013 to 20th October 2014. For the purposes of this feasibility study participants were followed up for 6 months (follow-up completed 20th October 2015).

Setting and participants

Participants were recruited through the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust orthopaedic clinics upon referral for rotator cuff surgery. Participants were eligible if they had ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings confirming massive rotator cuff full thickness tears (RoCT) (> 5 cm in size), with unacceptable pain and disability following conservative treatment or previous surgery that had failed and would be considered for patch surgery under routine clinical practice. Exclusion criteria were age < 18 years old; history of infection in the shoulder; neurological condition affecting the shoulder girdle; presence of rotator cuff arthropathy (secondary osteoarthritis of the glenohumeral joint as a result of a rotator cuff tear); current treatment for malignancy; pregnancy or lactation; currently participating in other research studies; or inability to give informed consent. Participants with contraindications to MRI were included but did not take part in the MRI component of the study.

Treatment allocation and interventions

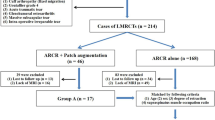

The particular intervention was determined in consultation between the surgeon and the participant (Fig. 1 and Additional file 1: Table 1). Management decisions were made at two stages. First, the surgeon and participant jointly made a decision between either conservative management (the anterior deltoid rehabilitation programme) or surgery. Second, an intraoperative decision on surgical management was made by the surgeon. If the torn tendon was mobile and could be pulled back to the tuberosity, arthroscopic repair was performed; if the torn tendon could be mobilised following release to within 1 cm of the tuberosity to allow attachment of a patch, repair was performed using a patch; and if the torn tendon could not be mobilised following release, a debridement was performed. In summary, participants in the ‘Patch’ group had elected surgical management and had massive cuff tears which could not be fully reduced at surgery but were suitable for repair by patch augmentation. The ‘Non-patch’ group had massive tears and elected for either non-surgical rehabilitation, or surgical intervention involving a procedure other than a patch.

Treatment allocation flowchart. Intervention was determined in consultation between the surgeon and the participant. Management decisions were made at two stages. First, the surgeon and participant jointly made a decision between either conservative management (the anterior deltoid rehabilitation programme) or surgery. Second, an intraoperative decision on surgical management was made by the surgeon: if the torn tendon was mobile and could be pulled back to the tuberosity, arthroscopic repair was performed; if the torn tendon could be mobilised following release enough to allow attachment of a patch, repair was performed using a patch; and if the torn tendon could not be mobilized following release, a debridement was performed

Patch properties

The Leeds Kuff Patch (Xiros, Leeds UK) is produced from polyethylene terephthalate (PET, polyester), a non-absorbable biocompatible material that has been in use for the reconstruction of ligaments and tendons for over 25 years. Early generations of artificial tissue contained polytetrafluorethylene and polypropylene, which resulted in inflammatory reactions within the surrounding tissues [34] . However, more modern techniques and materials promote new tissue ingrowth and minimize the occurrence of a foreign body reaction [35].

The design of the patch comprises a base component with an integral reinforcement component. This base component has an “open structure” that acts as a scaffold allowing tissue ingrowth. The polyester is rendered hydrophilic during the manufacturing process while the reinforcement provides enhanced strength for the patch.

Outcome measures and follow-up

Participants were followed up for 6 months with data collected using standardised case report forms at baseline (pre-treatment), 6 weeks and 6 months post-treatment. At all visits, clinical evaluations were performed. Baseline clinical data collection included age, gender, body mass index, duration of symptoms, range of movement, previous treatments for shoulder (including surgery), details of all therapies (including use of intraarticular therapies) in the previous 12 months. Participants completed a series of patient reported questionnaires at each visit to assess pain, function and patient satisfaction (Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) [36], Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) [37], and the Constant Score [38] and quality of life was assessed using the EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire (EQ-5D-5 L) [39]. An increase in the value of the OSS and Constant score at follow-up represents improvement, while for SPADI, a decreased score represents improvement in pain and function. Participants with no MRI contraindications had an MRI scan at baseline and 6 months.

MRI scans

MRI scans of the shoulder were performed using a pre-agreed protocol using a MAGNETOM Verio 3.0 T MRI system (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Fat and water images were generated from the Dixon images using the scanner vendor’s software. B0 variations due to changes in magnetic susceptibility at tissue interfaces were corrected for using a phase correction method [40]. Imaging analysis was performed using the OSIRIX system (Geneva, Switzerland). Images were contoured on the fat only images from the spinoglenoid notch medially to the first slice showing continuous bone marrow in the scapula laterally. This established a reproducible volume in patients, which did not suffer from signal drop off as previously described [41]. Regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn for the purpose of measuring fat fraction values. The 3 ROIs drawn outlined the supraspinatus fossa, bounded superiorly by the trapezius muscle (SSP), the suprapinatus remnant (SSP_RM) (defined as the muscle remnant within the SSP) and the infraspinatus muscle (Fig. 2). Fat fraction values were calculated for each ROI as the mean voxel value in the fat image ROI divided by the sum of the mean voxels values in the fat and the water images ROIs (fat/(fat+water)). Contouring was undertaken using the methods adopted by Zanetti et al. [41] by a single reader blinded to treatment allocation.

Muscles were also graded with the Goutallier Classification [42] using the 0–4 grading system.

Sample size

As no hypothesis testing was anticipated no formal power calculations were performed. Published evidence for pilot study sample size suggests that 30 patients per group represent a good balance between accuracy of effect size estimation and feasibility [43,44,45,46]. Therefore we aimed to recruit 60 patients in total. Early in the study the protocol was amended to enable over-recruitment in order to allow for the recruitment of participants who met study criteria but were ineligible for MRI whilst still ensuring a total of approximately 60 participants took part in the MRI component of the study.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using STATA software, version 13 (College Station, TX, USA 2013). To understand feasibility, methodological issues relevant to this study were reported according to the framework devised for feasibility studies by Shanyinde et al. [47, 48]. Recruitment and eligibility was assessed using rate of eligibility (%), the conversion of eligible to consent (%) and an assessment of whether required numbers sought were recruited. Adherence to the protocol was assessed qualitatively by broadly reviewing the study objectives against our findings, and the acceptability assessed using the attrition rate (%) [49]. The outcome data was assessed based on the amount of missing data (%) found in each case report form.

The patch and non-patch groups were compared descriptively at baseline. At 6 month follow-up, differences between the medians in each group and associated 95% confidence intervals were assessed using quantile regression, adjusting for baseline scores. The groups were also compared for the proportions in each group that had improvement greater than the previously-reported minimum clinically important difference (MCID) in each shoulder-specific outcome measure [50]. This was expressed as percentages and odds ratios with 95% CI and adjusted for the baseline score for each outcome. MCID for OSS was set at 5 units, SPADI at 15.4 [51] and Constant score at 10.4 [52]. No hypothesis testing was undertaken as the study did not aim to draw inferences from the data.

Exploratory sub-group analysis

To further understand outcomes, sub-group analyses were performed. The patch group was further sub-divided into a ‘Patch-better Group’, where the surgeon subjectively rated the patch repair to involve relatively good quality tendon as noted at surgery (i.e. little delamination, thick tendon), and a ‘Patch-poor Group’ with massive tears retracted to the level of the glenoid with poor quality tendons (i.e. frayed, delaminated thinned tendon). The control group was also sub-divided into those who underwent an arthroscopic repair (Non-patch arthroscopy Group) and those who underwent simple arthroscopic surgery, including debridement (Non-patch excluding arthroscopy Group). Comparisons were made between i) the patch poor group and the patch better group and ii) the non-patch arthroscopy and the non-patch excluding arthroscopy using quantile regression as described above.

Results

Feasibility outcomes

Recruitment & eligibility

A total of 81 patients were invited to participate, of whom 75 agreed to take part in the study (conversion to consent = 92.6%) and 72 met the eligibility criteria (rate of eligibility = 96.3%). Of the 72 recruited into the study four patients were withdrawn at baseline: 3 did not have a RoCT at baseline (2 on MRI and 1 on arthroscopy), and one patient asked to be withdrawn having undergone no surgical procedure. Therefore a total of 68 participants were allocated to an intervention arm: 29 to the patch group and 39 to the non-patch (control) group (Fig. 3).

Baseline characteristics were balanced across treatment arms (Table 1). Participants were on average (SD) 65.3 years old (9.18), 61% women, BMI of 28.8 (5.69) with symptom duration of a median 12 months.

Clinical outcome measures

There was a 100% completion rate for all questionnaires at baseline with respect to calculation of outcome scores, however 6 individuals (9%) (3 in each treatment arm) had missing data for the clinician-measured “range of motion” and “power” components of the Constant score (Table 2). At 6 months, completion rates to enable calculation of total scores across all questionnaires were high (90–97%), with slightly more missing data in the nonpatch group compared to the patch group.

Adherence & acceptability

The initial recruitment target of 60 participants (30 per arm) was achieved. Clinical data was collected using standardised outcome measures as set out in the protocol. The original protocol defined follow-up at 6 weeks and 6 months, however patients undergoing any form of surgery were struggling to perform the movement and strength elements of some of the outcome measures at 6 weeks. The 6 week follow-up visit was therefore stopped.

Overall attrition from the study at 6 months was moderate (16%), suggesting that the protocol was acceptable. A difference was observed in attrition between the patch and non-patch group (1 participant in the patch vs 10 in the non-patch group); half of the non-patch patients lost to follow-up were in the physiotherapy group. The mean follow up time from ‘date of procedure’ to 6 month follow-up was 227 days from an initial target of 180 days (6 months).

Clinical outcomes

Improvement was seen at follow-up for all clinical outcomes in both patch and control groups, except for the EQ-VAS which was slightly reduced in the control group (Table 3). Overall, improvements in the patch group were of a greater magnitude than for the non-patch control group. The median score was higher in the patch group compared to controls for the OSS (baseline-adjusted difference 9.76, 95% CI 2.25, 17.29, p = 0.01) and lower for SPADI (difference 22.97, 95% CI 3.0, 42.92, p = 0.03) but no substantive differences were seen for the total Constant score (p = 0.59). Compared to the non-patch group, the patch group had a greater proportion of participants demonstrating improvement (change greater than MCID) in two of the shoulder-specific patient reported outcomes, although not statistically significant: 78% vs 62% for OSS (Odds ratio 2.94, 95% CI 0.78, 11.02,p = 0.11); 63% vs 50% for SPADI (Odds ratio 2.66,95% CI 0.72,9.78, p = 0.15) but had a lower proportion of participants demonstrating improvement for the Constant score (50% vs 62% [Odds ratio 0.57,95% CI 0.18,1.90,p = 0.35)]. Quality of life scores (EQ-5D Index and EQ-VAS) were slightly improved in the patch group compared to the non-patch group.

Exploratory sub-group analysis

Results of the sub-analyses showed no substantive differences, all p > 0.05 (Table 4). All comparator groups showed improvement at 6-month follow up with slight variation in the magnitude between them. Compared to the patch-poor group, the patch-better group had better improvement in the Constant score (9.6 score difference between the groups) and less improvement in SPADI (2.4 score difference) having adjusted for their baseline scores; and no difference between the groups for OSS. The non-patch (excluding arthroscopy) group improved by a greater magnitude compared to the non-patch arthroscopy group in all 3 outcome scores although this was also not substantive.

MRI outcomes

Of the 68 patients eligible for the study, 58 underwent MRI at baseline. Of the patients who did not have a baseline MRI, eight had metallic implants contraindicated to MRI, while one suffered claustrophobia. Another patient attended the scan, but could not tolerate it so it was halted prematurely without sufficient images for analysis. At 6 month follow-up 54/58 underwent MRI, meaning 4 additional patients declining or not attending, alongside the still contraindicated 10 patients from baseline, totalling 14 who did not have the 6 month MRI. On analysis of the MRI scans, for 4 patients, the fat and water images could not be reconstructed from the “in” and “out of” phase images. One patient was imaged in the wrong plane: a technical error in MRI protocol. One patient subsequently withdrew from the study, so their data was not analysed. This resulted in 48 participants with paired MRI scores available: 22 in the Patch group, and 26 in the non-patch group. Complete paired Goutallier data was available for 41 participants.

In the full sample, there was only a slight increase in the fat fraction for supraspinatus (SSP; 53 to 55%) and the infraspinatus (ISP; 26 to 29%) while the supraspinatus remnant (SSP_RM) showed no change (Table 5). These differences were similar and in the same direction when the participants were analysed separately by treatment status (patch vs nonpatch).

A change in Goutallier classification was defined as a difference of at least 1 grade. For the SSP, 11 participants worsened over time (5 in the controls and 6 in the patch), while 30 remained the same and 1 improved. Results were similar for ISP and teres minor.

Discussion

The primary aim of this study was to determine the feasibility of conducting a randomised controlled trial using patch-assisted surgery. A definitive randomised control trial appears achievable in terms of recruitment, eligibility, acceptability and outcome measures. The secondary aim was to compare the clinical outcomes of patients with massive RoCTs who were managed with patch-assisted surgery against patients managed with traditional treatment options (non-surgical physiotherapy-based rehabilitation, arthroscopic repair, and arthroscopic debridement). Improvements in shoulder symptoms were found in both patch and control groups at 6 months, but a greater magnitude of improvement was observed in patients receiving patch repair.

To our knowledge this is the first study to compare synthetic patch repair with a number of common treatment modalities for large and massive rotator cuff tears, including conservative management. It is also novel to include MRI analysis of the rotator cuff before and after these treatment modalities. Previous studies investigating patch augmentation of large or massive rotator cuff repairs have mainly been case series [21, 31, 32] . Few studies comparing synthetic patch to other treatment methods for symptomatic rotator cuff tear have been reported. These generally involve similar patient numbers with massive RoCTs to the current study (ranging from 21 to 60 patients with patch repair), and include a comparison of the synthetic patch with no patch [53]; a comparison with biological collagen patch as well as standard repair group [54]; a comparison of patch plus bone marrow and arthroscopic cuff repair [55]; and patch Vs partial repair [56]. The synthetic patch demonstrated a lower retear rate, and improvement in various functional outcome measures and strength.

Feasibility outcomes

This feasibility study was designed as a pragmatic study, and thus randomisation and blinding was not assessed. A future larger scale study would likely compare patch-assisted surgery with non-patch assisted surgery, removing the non-surgical component within this feasibility study. As such, we would envisage the use of a standardised intra-operative decision system for surgeons, which would determine whether a participant was eligible for patch-assisted surgery and participants would be randomised at this point into one of two surgical treatment arms. Although the surgeon and potentially the patient (as a result of patch surgery requiring a larger opening, and therefore a larger scar, than non-patch arthroscopic surgery) would be aware of the treatment allocation, an independent assessor could conduct subsequent follow-up visits to reduce potential bias.

The moderate attrition rate at 6 months (11 lost to follow-up) suggests that the protocol was acceptable for participants; however, we did make the decision to remove the 6 week follow-up from the protocol early in the study due to the difficulty of patients in completing functional tests so early after any form of surgery. Missing data was minimal possibly due to the use of a number of routinely used shoulder questionnaires that were easy to complete. There was a noticeably lower completion rate/retention in the non-patch group, with half of these having received non-surgical management. It is possible that having made the decision not to proceed with surgery that these patients became disengaged from involvement in a ‘surgical’ study and there may also have been disengagement from the surgical team since these patients were no longer under their clinical care.

Various scoring systems are quoted in literature for post-operative assessment of rotator cuff surgery. In this current study we selected the OSS and Constant score, since they were the most well validated and frequently used to determine outcomes of RoCTs [9, 57]. In addition, we included the SPADI which has been shown to have reasonable validity and, although devised primarily as a rheumatological outcome score [37, 58], has been used to assess outcomes of RoCTs in the past [59]. We found that the Constant score had the most missing data fields of the three scores, which may reflect the multi-domain nature of the tool with functional tests which are difficult for some RoCT patients to complete and a mixture of patient-reported and clinician-reported outcomes. A recent systematic review of the psychometric properties of patient-reported outcomes in patients with rotator cuff disease found good evidence in support of the measurement properties of SPADI, limited overall evidence for OSS and mixed evidence for the Constant score, with positive evidence for responsiveness and reliability but negative evidence for hypothesis testing [60]. A recent international consensus process involving patients, clinicians and researchers, has defined the core outcome domains for shoulder disorder trials as ‘pain’, ‘physical functioning’, ‘global assessment of treatment success’ and ‘health-related quality of life’ [61]. Work to define a core outcome set based on these domains for clinical trials of people with shoulder pain is ongoing. A future study would therefore incorporate recommendations from this work to ensure alignment with international standards.

The level of MRI acceptability and attendance was high, despite ten patients with contraindications to such scans. In addition, the data available from the scans was of reasonable reliability and accuracy, with only 7 of the 48 paired scans having missing data for analysis of fat fraction and/or Goutallier Classification, which was due to technical errors with the protocols set for those patients’ scans.

Clinical outcomes

This study provides preliminary evidence that any standard shoulder intervention may provide improvement in outcome scores, but that patch repair provides greater improvement in all outcomes at 6 months. The differences between the patch group and controls were substantial (greater than MCID) for the Oxford Shoulder Score. On further subgroup analysis, no substantive differences were found between patch patients with good quality and poor quality tendons, although this finding may have been hampered by small numbers.

MRI outcomes at 6 months demonstrated little difference between the patch group and control group, with both groups demonstrating either similar or slightly worse (i.e. higher) fat fraction within the rotator cuff. It may be that 6 months is too early in the rehabilitation phase following any treatment method to note anatomical changes. To confirm our findings of clinically meaningful improvement using a patch, a definitive trial is needed.

Limitations

Due to the pragmatic, unblinded nature of the study, a patient’s treatment wishes were taken into consideration, which is common practice with surgical interventions. In this setting this was a feasible and ethical way to conduct the study but may potentially lead to bias.

This pragmatic nature allows assessment of a number of treatment measures for massive RoCTs, but this can lead to a heterogenous comparison group: the non-patch group of 39 patients included those undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, arthroscopic debridement of an irreparable tear, and non-operative physiotherapy management. However, in terms of participant demographic and baseline characteristics there were no substantive differences between groups.

The inclusion criteria for the study allowed patients to be eligible if they had ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings confirming massive rotator cuff full thickness tears (RoCT) (> 5 cm in size), with unacceptable pain and disability following conservative treatment or previous surgery that had failed and would be considered for patch surgery under routine clinical practice. This does mean there is a heterogeneous sample for both groups, (patch and non-patch) with some patients having primary massive tears, and others retears of previously repaired tendons. In this feasibility study, this was noted but did not form part of the outcome analysis. This factor could influence outcome measures, and in any subsequent trial following this feasibility study, this should be analysed.

The subgroup analysis into tendon quality and degree of retraction is subjective, and due to lower numbers compared in each group there was reduced power in those analyses. However, these analyses highlight important factors that could be could be useful for eligibility and stratification purposes in subsequent trials.

Of the baseline number of 68 participants, only 58 underwent MRI assessment prior to any intervention:, 8 participants did not have an MRI at baseline due to metallic implants, 1 due to claustrophobia and another became claustrophobic during the first scan. Therefore, although patients had legitimate reasons for failure to complete MRI assessment, this led to a reduction in the number of scans possible to assess. For this reason, we amended the protocol to allow additional recruitment to the study to compensate for those ineligible for the MRI. At 6 months, a further 4 declined or failed to attend. The drop-out rate for those eligible for MRI assessment was acceptable, suggesting that the MRI was an acceptable component of the protocol, although over a longer follow-up it is possible that this number would decrease further.

The two point Dixon imaging technique employed did not correct for T2* effects, eddy currents, noise related bias or the spectral complexity of fat.

Conclusion

Promising short-term results can be achieved using patch augmentation for massive RoCTs. This study suggests that a patch may be beneficial, and given the positive outcomes from this study, a larger trial to investigate patch surgery is feasible.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- EQ-5D-5 L:

-

EuroQol five dimensions questionnaire

- ISP:

-

Infraspinatus

- MCID:

-

Minimum clinically important difference

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- OSS:

-

Oxford Shoulder Score

- PET:

-

Polyethylene terephthalate

- RoCT:

-

Rotator cuff tear

- SPADI:

-

Shoulder Pain and Disability Index

- SSP:

-

Supraspinatus

- SSP_RM:

-

Supraspinatus remnant

- TS:

-

Tangent sign

- UCLA:

-

University of California at Los Angles

- VAS:

-

Visual analogue score

- VIBE:

-

Volumetric interpolated breath-hold examination

References

Linsell L, Dawson J, Zondervan K, Rose P, Randall T, Fitzpatrick R, et al. Prevalence and incidence of adults consulting for shoulder conditions in UK primary care; patterns of diagnosis and referral. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2006;45:215–21.

Mitchell C, Adebajo A, Hay E, Carr A. Shoulder pain: diagnosis and management in primary care. Bmj. 2005;331:1124–8.

Sakurai G, Ozaki J, Tomita Y, Kondo T, Tamai S. Incomplete tears of the subscapularis tendon associated with tears of the supraspinatus tendon: cadaveric and clinical studies. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 1998;7:510–5.

Aoki M, Okamura K, Fukushima S, Takahashi T, Ogino T. Transfer of latissimus dorsi for irreparable rotator-cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:761–6.

Moore DR, Cain EL, Schwartz ML, Clancy WG Jr. Allograft reconstruction for massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:392–6.

DeOrio JK, Cofield RH. Results of a second attempt at surgical repair of a failed initial rotator-cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:563–7.

Rees JL. The pathogenesis and surgical treatment of tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90:827–32.

Fuchs B, Gilbart MK, Hodler J, Gerber C. Clinical and structural results of open repair of an isolated one-tendon tear of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:309–16.

Carr A, Cooper C, Campbell MK, Rees J, Moser J, Beard DJ, et al. Effectiveness of open and arthroscopic rotator cuff repair (UKUFF). Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:107.

Gurnani N, van Deurzen DFP, van den Bekerom MPJ. Shoulder-specific outcomes 1 year after nontraumatic full-thickness rotator cuff repair: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Shoulder Elbow. 2017;9:247–57.

Bjorkenheim JM, Paavolainen P, Ahovuo J, Slatis P. Surgical repair of the rotator cuff and surrounding tissues. Factors influencing the results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988:148–53.

Gazielly DF, Gleyze P, Montagnon C. Functional and anatomical results after rotator cuff repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994:43–53.

Harryman DT 2nd, Mack LA, Wang KY, Jackins SE, Richardson ML, Matsen FA 3rd. Repairs of the rotator cuff. Correlation of functional results with integrity of the cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73:982–9.

Thomazeau H, Boukobza E, Morcet N, Chaperon J, Langlais F. Prediction of rotator cuff repair results by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997:275–83.

Duralde XA, Bair B. Massive rotator cuff tears: the result of partial rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2005;14:121–7.

Franceschi F, Papalia R, Vasta S, Leonardi F, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Surgical management of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2015;23:494–501.

Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic treatment of massive rotator cuff tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001:107–18.

Liem D, Lengers N, Dedy N, Poetzl W, Steinbeck J, Marquardt B. Arthroscopic debridement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:743–8.

Lo IK, Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic repair of massive, contracted, immobile rotator cuff tears using single and double interval slides: technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:22–33.

Berth A, Neumann W, Awiszus F, Pap G. Massive rotator cuff tears: functional outcome after debridement or arthroscopic partial repair. J Orthop Traumatology. 2010;11:13–20.

Castagna A, Garofalo R, Cesari E. No prosthetic management of massive and irreparable rotator cuff tears. Shoulder Elbow. 2014;6:147–55.

Delaney RA, Lin A, Warner JJ. Nonarthroplasty options for the management of massive and irreparable rotator cuff tears. Clin Sports Med. 2012;31:727–48.

Irlenbusch U, Bracht M, Gansen HK, Lorenz U, Thiel J. Latissimus dorsi transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: a longitudinal study. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2008;17:527–34.

Merolla G, Chillemi C, Franceschini V, Cerciello S, Ippolito G, Paladini P, et al. Tendon transfer for irreparable rotator cuff tears: indications and surgical rationale. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4:425–32.

Galatz LM, Ball CM, Teefey SA, Middleton WD, Yamaguchi K. The outcome and repair integrity of completely arthroscopically repaired large and massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-a:219–24.

Gerber C, Fuchs B, Hodler J. The results of repair of massive tears of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:505–15.

Senekovic V, Poberaj B, Kovacic L, Mikek M, Adar E, Markovitz E, et al. The biodegradable spacer as a novel treatment modality for massive rotator cuff tears: a prospective study with 5-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2017;137:95–103.

Badhe SP, Lawrence TM, Smith FD, Lunn PG. An assessment of porcine dermal xenograft as an augmentation graft in the treatment of extensive rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17:35s–9s.

Nada AN, Debnath UK, Robinson DA, Jordan C. Treatment of massive rotator-cuff tears with a polyester ligament (Dacron) augmentation: clinical outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92:1397–402.

Burkhead WZ Jr, Schiffern SC, Krishnan SG. Use of graft jacket as an augmentation for massive rotator cuff tears. Semin Arthroplast. 2007;18:11–8.

Kim SJ, Lee IS, Kim SH, Lee WY, Chun YM. Arthroscopic partial repair of irreparable large to massive rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2012;28:761–8.

Arrigoni P, Fossati C, Zottarelli L, Ragone V, Randelli P. Functional repair in massive immobile rotator cuff tears leads to satisfactory quality of living: results at 3-year follow-up. Musculoskelet Surg. 2013;97(Suppl 1):73–7.

Rangan A, Upadhaya S, Regan S, Toye F, Rees JL. Research priorities for shoulder surgery: results of the. James Lind Alliance patient and clinician priority setting partnership. BMJ Open. 2015;2016:6.

Legnani C, Ventura A, Terzaghi C, Borgo E, Albisetti W. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with synthetic grafts. A review of literature. Int Orthop. 2010;34:465–71.

Sinagra ZP, Kop A, Pabbruwe M, Parry J, Clark G. Foreign body reaction associated with artificial LARS ligaments: a retrieval study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6:2325967118811604.

Dawson J, Rogers K, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. The Oxford shoulder score revisited. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:119–23.

Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, Lertratanakul Y. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res. 1991;4:143–9.

Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987:160–4.

Herdman M, Gudex C, Lloyd A, Janssen M, Kind P, Parkin D, et al. Development and preliminary testing of the new five-level version of EQ-5D (EQ-5D-5L). Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1727–36.

Zanetti M, Gerber C, Hodler J. Quantitative assessment of the muscles of the rotator cuff with magnetic resonance imaging. Investig Radiol. 1998;33:163–70.

Goutallier D, Postel JM, Bernageau J, Lavau L, Voisin MC. Fatty muscle degeneration in cuff ruptures. Pre- and postoperative evaluation by CT scan. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994:78–83.

Billingham SAM, Whitehead AL, Julious SA. An audit of sample sizes for pilot and feasibility trials being undertaken in the United Kingdom registered in the United Kingdom clinical research network database. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:104.

Hertzog MA. Considerations in determining sample size for pilot studies. Res Nurs Health. 2008;31:180–91.

Whitehead AL, Julious SA, Cooper CL, Campbell MJ. Estimating the sample size for a pilot randomised trial to minimise the overall trial sample size for the external pilot and main trial for a continuous outcome variable. Stat Methods Med Res. 2016;25:1057–73.

Moore C, Nietert S. Recommendations for planning pilot studies in clinical and translational research. Clin Translational Sci. 2011;4:332–7.

Shanyinde M, Pickering RM, Weatherall M. Questions asked and answered in pilot and feasibility randomized controlled trials. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2011;11:117.

Bugge C, Williams B, Hagen S, Logan J, Glazener C, Pringle S, et al. A process for decision-making after pilot and feasibility trials (ADePT): development following a feasibility study of a complex intervention for pelvic organ prolapse. Trials. 2013;14:353.

Lee EC, Whitehead AL, Jacques RM, Julious SA. The statistical interpretation of pilot trials: should significance thresholds be reconsidered? BMC Med Res Methodol. 2014;14:41.

Dettori JR. Loss to follow-up. Evid Based Spine Care J. 2011;2:7–10.

Ekeberg OM, Bautz-Holter E, Keller A, Tveitå EK, Juel NG, Brox JI. A questionnaire found disease-specific WORC index is not more responsive than SPADI and OSS in rotator cuff disease. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:575–84.

Kukkonen J, Kauko T, Vahlberg T, Joukainen A, Äärimaa V. Investigating minimal clinically important difference for Constant score in patients undergoing rotator cuff surgery. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2013;22:1650–5.

Vitali M, Cusumano A, Pedretti A, Naim Rodriguez N, Fraschini G. Employment of synthetic patch with augmentation of the long head of the biceps tendon in irreparable lesions of the rotator cuff: our technique applied to 60 patients. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2015;19:32–9.

Ciampi P, Scotti C, Nonis A, Vitali M, Di Serio C, Peretti GM, et al. The benefit of synthetic versus biological patch augmentation in the repair of posterosuperior massive rotator cuff tears: a 3-year follow-up study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42:1169–75.

Yoon JP, Chung SW, Kim JY, Lee BJ, Kim HS, Kim JE, et al. Outcomes of combined bone marrow stimulation and patch augmentation for massive rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:963–71.

Mori D, Funakoshi N, Yamashita F. Arthroscopic surgery of irreparable large or massive rotator cuff tears with low-grade fatty degeneration of the infraspinatus: patch autograft procedure versus partial repair procedure. Arthroscopy. 2013;29:1911–21.

Piper CC, Hughes AJ, Ma Y, Wang H, Neviaser AS. Operative versus nonoperative treatment for the management of full-thickness rotator cuff tears: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2018;27:572–6.

Varghese M, Lamb J, Rambani R, Venkateswaran B. The use of shoulder scoring systems and outcome measures in the UK. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2014;96:590–2.

Roy JS, MacDermid JC, Woodhouse LJ. Measuring shoulder function: a systematic review of four questionnaires. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;61:623–32.

Huang H, Grant JA, Miller BS, Mirza FM, Gagnier JJ. A systematic review of the psychometric properties of patient-reported outcome instruments for use in patients with rotator cuff disease. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2572–82.

Page MJ, Huang H, Verhagen AP, Buchbinder R, Gagnier JJ. Identifying a core set of outcome domains to measure in clinical trials for shoulder disorders: a modified Delphi study. RMD Open. 2016;2:e000380.

Gagnier JJ, Page MJ, Huang H, Verhagen AP, Buchbinder R. Creation of a core outcome set for clinical trials of people with shoulder pain: a study protocol. Trials. 2017;18:336.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Mo Ismail, Anand Karmegan, Krishna Kumar, Ravi Putteswamiah and Simon Fogarty for support with participant recruitment and data collection.

Funding

This study was funded by a Leeds Teaching Hospitals Charitable Foundation Pilot Project Award (Ref R&D/PP/1305). PG, SRK and BD are supported by the Arthritis Research UK Experimental Osteoarthritis Treatment Centre (Ref 20083) and the UK NIHR Leeds Biomedical Research Centre. JDB is funded by a National Institute for Health Research and Health Education England, Clinical Lectureship. This paper presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and Health Education England. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the UK Department of Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RH – study concept and design, acquisition of data, drafting manuscript, final approval; BD – data analysis and interpretation of data, drafting manuscript, final approval; PC – acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation of data, drafting manuscript, final approval; AG, JDB, MS, DS - data analysis and interpretation of data, drafting manuscript, final approval; PGC - study concept and design, drafting manuscript, final approval; SRK - study concept and design, acquisition of data, data analysis and interpretation of data, drafting manuscript, final approval. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrolment into the study. The study was approved by Leeds West Research Ethics Committee (13/YH/0030).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

RH - consults for Xiros, Leeds UK, and received fees for each patch used by another surgeon. BD, PC, AJG, JDB, MS, DS, PGC, SRK declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Table S1.

Description of surgical interventions

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Cowling, P., Hackney, R., Dube, B. et al. The use of a synthetic shoulder patch for large and massive rotator cuff tears – a feasibility study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 21, 213 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03227-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-020-03227-z