Abstract

Background

A stress fracture (SF) is a highly debilitating injury commonly experienced in United States Army Basic Combat Training (BCT). Body fat (BF) may be associated with this injury but previous investigations (in athletes) have largely used SF self-reports and lacked sufficient statistical power. This investigation developed an equation to estimate %BF and used that equation to examine the relationship between %BF and SF risk in BCT recruits.

Methods

Data for the %BF predictive equation involved 349 recruits with BF obtained from dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. %BF was estimated using body mass index (BMI, weight/height2), age (yr), and sex in the entire population of BCT recruits over an 11-year period (n = 583,651). Medical information was obtained on these recruits to determine SF occurrence. Recruits were separated into deciles of estimated %BF and the risk of SFs determined in each decile.

Results

The equation was %BF = − 7.53 + 1.43 ● BMI + 0.13 ● age − 14.73 ● sex, with sex either 1 for men or 0 for women (r = 0.88, standard error of estimate = 4.2%BF). Among the men, SF risk increased at the higher and lower %BF deciles: compared to men in the mean %BF decile, the risk of a SF for men in the first (lowest %BF) and tenth (highest %BF) decile were 1.27 (95%confidence interval (95%CI) = 1.17–1.40) and 1.15 (95%CI = 1.05–1.26) times higher, respectively. Among women, SF risk was only elevated in the first %BF decile with risk 1.20 (95%CI = 1.09–1.32) times higher compared to the mean %BF decile.

Conclusions

Low %BF was associated with higher SF risk in BCT; higher %BF was associated with higher SF risk among men but not women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A stress fracture (SF) is a serious and debilitating injury commonly seen in United States (US) Army Basic Combat Training (BCT). Previous studies found medically diagnosed SF incidence in BCT to range from 0.8 to 5.1% for men and 1.1 to 18.0% among women [1,2,3,4,5,6,7]. SFs often require removal from BCT and supervised rehabilitation that lasts an average of 62 days [8]. Well researched factors increasing susceptibility to SFs in BCT include female gender [2, 3, 9, 10, 11], older age [9, 12, 13], and race/ethnicity other than black [2, 9, 12,13,14,15]. The association between SF risk and physical characteristics like height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) is not clear because results were mixed in the various investigations [9, 14, 16,17,18,19,20,21]. No study to date has examined the association between SF risk and body fat (BF) in BCT, but there have been several investigations examining this association in athletes [22,23,24,25]. However, in most of these investigations [22,23,24] SFs were self-reported and all [22,23,24,25] involved few athletes with SFs (n ≤ 31) suggesting low statistical power.

BMI is generally taken as a surrogate for BF since it has a close relationship to %BF with correlations on the order of 0.7 [26,27,28]. However, a particular absolute BMI level does not reflect the same level of body fat in men and women. Examination of the data in a previous BCT study showed that for the same BMI, women had 13 to 15% more BF [26]. Multiple regression equations that have included age, sex, and/or race/ethnicity in addition to BMI have shown improved ability to predict %BF with correlation ranging from 0.81 to 0.91 [28,29,30,31,32,33].

This investigation examines the ability of BMI, age, sex, and race to predict %BF in a cohort of recruits in BCT. After developing and validating a %BF predictive equation, this investigation uses that equation to examine the association between %BF and SF risk in the entire population of US Army recruits attending BCT over an 11-year period. A specific %BF equation developed using military recruits would appear to be the most appropriate to examine this relationship in BCT. Based on previous studies [28,29,30,31,32,33,34] it was hypothesized that an equation using BMI, age, sex, and race/ethnicity should produce a correlation with a direct measure of %BF in the range of 0.81 to 0.91. It was also hypothesized that both high and low %BF would increase the risk of SFs based on studies that have observed this relationship between BMI and %BF [9, 35].

Methods

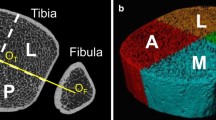

This study involved a secondary analysis of data from past investigations that was approved by Human Subjects Protection Office of the US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine. Four legacy databases were used, one to develop a %BF prediction equation and the others to apply this predictive equation to examine the relationship between %BF and SF risk. The database used to develop the %BF predictive equation contained date of birth, height, weight, sex, race/ethnicity, and percent body fat (%BF) on 180 male and 169 female BCT recruits. [36] Height was measured with a stadiometer (Model GPM, Seritex Inc., Carlstadt, NJ) and weight with a digital scale (Model 770, Seca Corp., Columbia MD) with subjects in T-shirts, shorts, underclothing, and socks. Date of birth, sex, and race/ethnicity were self-reported. Body fat (BF) was measured with dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA, Model DPXL, Lunar Corp., Madison WI) [36]. Scanning with the DXA began at the head and progressed in 1-cm segments to the feet with the machine set to the faster 10-min scanning speed. The Lunar software (version 3.6) was used to provide %BF for each participant. Coefficients of variation for measuring fat mass using DXA have ranged from 0.8 to 5.0% [37].

A database of all recruits attending BCT between 1997 and 2007 was compiled from three databases by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch (AFHSB) of the Defense Health Agency. The first of these databases was the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC) Master Personnel File which was searched from January 1997 to December 2007 (11-year period) to identify individuals based on their first demographic record (indicating entry into the Army), with a rank of private (E1) to specialist (E4), and 17 to 35 years of age. DMDC database also provided birth year and race/ethnicity. The second AFHSB database was the Defense Medical Surveillance System which provided the injury data on recruits identified in the DMDC database. Specific International Classification of Diseases, Version 9, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) codes were searched for the inclusive time from each recruit’s first DMDC record to 10 weeks after the first DMDC record. This covered the period of BCT plus time in the reception station (where recruits are initially in-processed). SF cases were recruits with the occurrence of an ICD-9 code for pathological fractures or SFs (ICD-9 codes 733.1–733.19 and 733.93–733.98). Pathological fracture codes were included because, prior to 2001, there was no ICD-9 code specifically for SFs and the 733.1–733.19 series contained the codes that clinicians in military facilities were instructed to use for this purpose. It was previously shown that use of the pathological fracture codes rapidly declined shortly after the SF codes were introduced, supporting the concept that clinicians were using the pathological fracture codes for SFs prior to having specific SF codes [38]. The third AFHSB database was that of the Military Entrance Processing Station which provided sex, height, and weight of the recruits. The AFHSC provided the investigators with a single de-identified database linking information from these three databases.

In all databases where available, age was calculated as year of entry into BCT minus birth year. BMI was calculated as weight/height2. In the database used to develop the %BF predictive equation, non-linear regression techniques were applied, but they accounted for little additional variance in %BF compared to linear techniques so the latter was used to develop the equation. Predictive residual sums of squares (PRESS) statistics were used to cross-validate the %BF predictive equation [39]. PRESS statistics compute residual errors based on successive removal and subsequent replacement of cases. These PRESS-residuals are summed and replace the residual sum of squares for the entire model to provide a modified correlation coefficient (r-value) and standard error of estimate (SEE).

SF incidence was calculated as: recruits with one or more SFs / total number of recruits X 1000 (cases/1000 recruits). Univariate logistic regression was performed to quantify risk of SFs at deciles of estimated %BF. Simple contrasts were used, comparing the risk at a baseline (referent) decile of %BF (defined with a risk ratio of 1.00) to other deciles of that variable. The baseline decile of %BF was selected such that it included the mean BF value. A multivariate logistic regression model was constructed with SF incidence as the dependent variable and race/ethnicity and %BF as independent variables to see if race/ethnicity modified the relationship between %BF and SF incidence. In both regression models, odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95%CI) were calculated comparing each decile to the referent decile. Statistical Software for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 24.0) was used to analyze all data.

Results

The addition of BMI, age, and sex to the regression model accounted for significant portions of the variance in DXA %BF (p < 0.05) but race/ethnicity did not (p = 0.94). The racial distribution of the BCD sample was 55.01% White, 28.65% Black, 12.32% Hispanic, 2.29% Asian, 1.43% American Indian, and 1 recruit without race specified. The resulting multiple linear regression equation was:

where BMI was in kg/m2, age in years, and sex coded as either 1 (men) or 0 (women). For this equation, the r = 0.88 and the SEE = 4.2 %BF. The PRESS estimated r-value was 0.84 and the SEE was 4.2 %BF. Adding interaction terms (age X BMI, age X sex, BMI X sex) accounted for little additional variance (r < 0.01). Age and physical characteristics of the men and women in the database used to develop the predictive equation are shown in Table 1.

The database containing all individuals in BCT between 1997 and 2007 included 614,606 recruits. Of these, 30,955 recruits (5.0%) were missing either birth year, gender, height, and/or weight and were not considered further in the analysis. The final dataset used for analysis contained 583,651 recruits, with 475,745 men and 107,906 women. Age and physical characteristics of these recruits are shown in Table 1.

The overall SF incidence was 1.9% for men and 8.0% for women as reported previously [38]. Table 2 shows the SF risk for men and women by deciles of estimated %BF. The men demonstrated a bimodal relationship with elevated SF risk in the lowest and highest %BF groups compared to the decile containing the mean %BF. The women had high SF risk at the lowest %BF decile compared to the mean %BF decile, but the SF risk at the higher BF deciles were similar to the mean decile.

Table 3 shows that the addition of race to the logistic regression model did little to modify the relationship between %BF and SF risk. Race was an independent risk factor in the multivariate model with black recruits having lower SF risk than other race/ethnic groups.

Discussion

The major finding of the study was that women and men in the lowest decile of body fatness had a 20–27% higher relative risk of developing a SF during BCT. Moreover, men in the upper most decile had a 15% greater risk of SFs compared to men in the mean BF decile. The same did not hold for women, however. Gender differences in fat mass and bioavailability of estrogens in young adults [40] may provide a partial explanation for the sex differences at the higher %BF levels. Estrogens have positive effects on bone formation [41] and adipocytes produce estrogens [42]. Thus, women with higher %BF may have similar SF risk to women with less BF because of higher estrogen levels. The increase in SF risk at the lowest BF deciles may be related to frame size. In previous studies, low BF was associated with smaller bone width, reflective of small frames size [43], and individuals with smaller tibia and femur widths were more likely to experience lower body SFs in basic training [16].

To examine the contribution of %BF to the risk of developing a SF during BCT, an equation was derived to predict %BF, as %BF is not routinely measured on recruits. Our hypothesis that there would be an acceptable strength of the association between predicted and actual %BF using BMI, age and sex was confirmed as the resulting equation had an r = 0.88 and a standard error of estimate of 4.2%BF, which was very similar to the strength of associations and errors of estimate derived by others [28,29,30,31,32,33] (see Table 3). Inclusion of race did little to improve the model. Initially it was assumed that race could contribute to the predictability of %BF because of known racial differences in body composition [34]. However, other investigations [29, 31] that have examined or included race/ethnicity in their %BF predictive equations also showed that this variable contributes little to the prediction of %BF when BMI, age and gender were included. The present study did find that individuals self-reporting as black had a lower risk of SFs than other racial groups, a finding that has been replicated in many other investigations [2, 9, 12,13,14,15]. The lower SF risk among blacks could be partly related to the higher bone mineral density and thicker bone cortical areas of blacks compared to other racial/ethnic groups [44,45,46,47]. The racial difference in bone mineral density between blacks and whites persists after adjustments for body composition, dietary history, sun exposure, biochemical bone markers, lifestyle characteristics, and other factors [47].

The PRESS statistic produced an r-value and SEE that were very similar to that obtained from the original data in the multiple linear regression model. This indicated that that the original model was consistent and that the equation produced an adequate prediction of %BF from BMI, age, and gender in our sample of male and female recruits. Future BCT studies that collect height, weight, age and gender may be able to use this equation to predict %BF.

Although no previous study has examined associations between SF risk and body fat in BCT, three studies have prospectively examined associations between BF and overall BCT injury risk [3, 5, 48]. Jones et al. [3] found a trend for a bimodal relationship between time-loss injuries and skinfold determined %BF in male recruits (n = 124) but not female recruits (n = 186). Knapik et al. [48] found a trend toward increasing risk of injuries of any type when the lowest DXA-determined %BF tertile was compared with the highest %BF tertile among both men (n = 169) and women (n = 164). Westphal et al. [5] actually found a trend indicating lower risk of any injury and time-loss injury among groups with the highest and lowest %BF groups compared to women in a mid %BF range (n = 156). These equivocal results may be partially explained by the relatively low sample sizes, few injury cases, and likely low statistical power. In the present study, we included 95% of recruits who attended BCT over an 11-year period which included a very large number of SFs (n = 17,811).

At least four investigations have examined the association between %BF and SFs in athletes. One study [22] of elite female runners (n = 19 reporting SFs and 19 not reporting SFs) found that DXA-determined %BF was lower but not significantly different among women self-reporting a previous history of SFs (16.6% vs 17.4%, p > 0.05). Another study [23] of university male and female lacrosse players (n = 5 men with and 30 men without SFs; n = 7 women with and 42 without SFs) also found no relationship between %BF (determined with a Tanita MC-190 body composition analyzer) and self-reported SFs. A third study of 54 female runners (n = 22 with SFs) found no difference in %BF between SF cases (17.0% BF) and non-SF cases (17.7% BF) (p > 0.05). Finally, the fourth study [25] matched 19 athletes with diagnosed SFs (by X-ray, bone scan, or magnetic resonance imaging) with 19 healthy athletes without SFs and found no significant difference in DXA-determined %BF between the two groups (p = 0.31). Most studies [22,23,24] relied on self-reports of SFs and all [22,23,24,25] had few SF cases, likely making them underpowered to detect a significant relationship between SF and %BF. Further, these studies [22,23,24,25] compared average %BF among those with and without SFs and did not compare risk at various %BF levels as reported in the present study.

Several previous studies have examined the ability of BMI, age, gender, and/or race to predict %BF [28,29,30,31,32,33] and data on these studies and the equations developed are shown in Table 4. Compared to the present investigation, these previous studies used samples that possessed more diversity in terms of age, BMI, and %BF. Yet the equation produced here has similar level of prediction strength as these other studies.

Limitations to this study should be noted. The %BF body fat equation developed here was based on a sample of Army recruits and the predictive equation is most appropriately applied to this population. Nonetheless, men and women entering the Army come from a wide-ranging cross-section of the US and are broadly representative of individuals of similar age within this national population. The most obvious limitation is that the %BF values in this study were estimated from a predictive equation. Studies should be conducted that measure actual BF in a large group of recruits and follow those recruits through BCT to obtain SF incidence and examine if the relationships established here are confirmed.

Conclusion

In summary, we developed a useful equation to predict %BF in US Army recruits and showed that this equation (using BMI, age, and sex) was consistent and produced an adequate prediction of %BF. We applied this equation to show that SF risk was higher among male and female recruits with low %BF and among male recruits with higher body fat.

Abbreviations

- %BF:

-

Percent body fat

- 95%CI:

-

95% Confidence interval

- AFHSB:

-

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch

- BCT:

-

Basic combat training

- BF:

-

Body fat

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- DMDC:

-

Defense Manpower Data Center

- DXA:

-

dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry

- ICD-9:

-

International Classification of Diseases

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PRESS:

-

Predictive residual sums of squares

- SEE:

-

Standard error of estimate

- SF:

-

Stress fracture

- US:

-

United States

References

Reinker KA, Ozburne S. A comparison of male and female orthopedic pathology in basic training. Milit Med. 1979;144:532–6.

Brudvig TGS, Gudger TD, Obermeyer L. Stress fractures in 295 trainees: a one-year study of incidence as related to age, sex, and race. Milit Med. 1983;148:666–7.

Jones BH, Bovee MW, Harris JM, Cowan DN. Intrinsic risk factors for exercise-related injuries among male and female Army trainees. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:705–10.

Bensel CK, Kish RN. Lower extremity disorders among men and women in Army basic training and effects of two types of boots. Natick: U.S. Army Natick Research and Development Laboratories Technical TR-83/026 TR-83/026; 1983.

Westphal KA, Friedl KE, Sharp MA, King N, Kramer TR, Reynolds KL, Marchitelli LJ. Health, performance and nutritional status of U.S. Army women during basic combat training. Natick: U.S. Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine Technical Report Number T96–2; 1995.

Pester S, Smith PC. Stress fractures of the lower extremities of soldiers in basic training. Orthop Rev. 1992;21:297–303.

Knapik JJ, Montain SJ, McGraw S, Grier T, Ely M, Jones BH. Stress fracture risk factors in basic combat training. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:940–6.

Hauret KG, Shippey DL, Knapik JJ. The physical training and rehabilitation program: duration of rehabilitation and final outcome of injuries in basic combat training. Milit Med. 2001;166:820–6.

Mattila VM, Niva M, Kiuru M, Pihlajmaki H. Risk factors for bone stress injuries: a follow-up study of 102,515 person-years. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:1061–6.

Macleod MA, Houston AS, Sanders I, Anagnostopoulos C. Incidence of trauma related to stress fractures and shin splints in male and female Army recruits: retrospective case study. Br Med J. 1999;318:29.

Protzman RR, Griffis CC. Comparative stress fracture incidence in males and females in equal training environments. Athl Train. 1977;12:126–30.

Lappe JM, Stegman MR, Recker RR. The impact of lifestyle factors on stress fractures in female Army recruits. Osteopros Int. 2001;12:35–42.

Gardner LI, Dziados JE, Jones BH, Brundage JF, Harris JM, Sullivan R, Gill P. Prevention of lower extremity stress fractures: a controlled trial of a shock absorbent insole. Am J Public Health. 1988;78:1563–7.

Kelly EW, Johnson SR, Cohen ME, Shaffer R. Stress fractures of the pelvis in female navy recruits: an analysis of possible mechanisms of injury. Milit Med. 2000;165:142–6.

Friedl KE. Body composition and military performance: origins of the Army standards. In: Marriott BM, Grumstrup-Scott J, editors. Body composition and military performance. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1992. p. 31–55.

Beck TJ, Ruff CB, Mourtada FA, Shaffer RA, Maxwell-Williams K, Kao GL, Sartoris DJ, Brodine S. Dual energy X-ray absorptiometry derived structural geometry for stress fracture prediction in male US marine corps recruits. J Bone Mineral Res. 1996;11:645–53.

Giladi M, Milgrom C, Simkin A, Danon Y. Stress fractures. Identifiable risk factors. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:647–52.

Finestone A, Shlamkovitch N, Eldad A, Laor A, Danon YL, Milgrom C. Risk factors for stress fractures among Israeli infantry recruits. Milit Med. 1991;156:528–30.

Shaffer RA, Rauh MJ, Brodine SK, Trone DW, Macera CA. Predictors of stress fractures in young female recruits. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:108–15.

Valimaki VV, Alfthan E, Lehmuskallio E, Loyttyniemi E, Sah T, Suominen H, Valimakii MJ. Risk factors for clinical stress fractures in male military recruits: a prospective cohort study. Bone. 2005;37:267–73.

Givon U, Friedman E, Reiner A, Vered I, Finestone A, Shemer J. Stress fractures in the Israeli defense forces from 1995 to 1996. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;373:227–32.

Duckham RL, Peirce N, Meyer C, Summers GD, Cameron N, Brooke-Wavell K. Risk factors for stress fractures in female endurance athletes: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e001920.

Wakamatsu K, Sakuraba K, Suzuki Y, Maruyama A, Tsuchiya Y, Shikakura J, El O. Association between stress fracture and bone metabolism/quality markers in lacrosse players. Open Access J Sports Med. 2012;3:67–71.

Bennell KL, Malcolm SA, Thomas SA, Ebeling PR, McCrory PR, Wark JD, Brukner PD. Risk factors for stress fractures in female track-and-field athletes: a retrospective analysis. Clin J Sports Med. 1995;5:229–35.

Schnackenburg KE, MacDonald HM, Ferber R, Wiley JP, Boyd SK. Bone quality and muscle strength in female athletes with lower limb stress fractures. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43:2110–9.

Knapik JJ, Burse RL, Vogel JA. Height, weight, percent body fat and indices of adiposity for young men and women entering the U.S. Army. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1983;54:223–31.

Roche AF, Siervogel RM, Chumlea WM, Webb P. Grading body fatness from limited anthropometric data. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:2831–8.

Deurenberg P, Weststrate JA, Seidell JC. Body mass index as a measure of body fatness: age- and sex-specific prediction formulas. Brit J Nutr. 1991;65:105–14.

Gallagher D, Visser M, Supulveda D, Pierson RN, Harris T, Heymsfield SB. How useful is body mass index for comparison of body fat across age, sex and ethnic groups. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;143(3):228–39.

Gallagher D, Heymsfield SB, Heo M, Jebb SA, Murgatroyd PA, Sakamoto Y. Healthy percent body fat ranges: an approach for developing guidelines on body mass index. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000;72:694–701.

Jackson AS, Stanforth PR, Gagnon J, Rankinen T, Leon AS, Rao DC, Skinner JS, Bouchard C, Wilmore JH. The effect of sex, age, and race on estimating percentage of body fat from body mass inde: the heritage family study. Int J Obes. 2002;26:789–96.

Pasco JA, Nicholson GC, Brennan SL, Kotowicz MA. Prevalence of obesity and the relationship between the body mass index and body fat: cross-sectional, population-based data. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29580.

Gomez-Ambrosi J, Silva C, Galofre JC, Escalada J, Santos S, Millan D, Vila N, Ibanez P, Gil MJ, Valenti V, et al. Body mass index classification misses subjects with increased cardiometabolic risk factors related to elevated adiposity. Int J Obes. 2012;36:286–94.

Fernandez JR, Heo M, Heymsfield SB, Pierson RN, Pi-Sunyer FX, Wang ZM, Wang J, Hayes M, Allison DB, Gallagher D. Is percent body fat differentially related to body mass index in Hispanic Americans, African Americans, and European Americans? Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:71–5.

Rauh MJ, Macera CA, Trone DW, Shaffer RA, Brodine SK. Epidemiology of stress fracture and lower-extremity overuse injuries in female recruits. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38:1571–7.

Sharp MA, Knapik JJ, Patton JF, Smutok MA, Hauret K, Chervak M, Ito M, Mello RP, Frykman PN, Jones BH. Physical fitness of soldiers entering and leaving basic combat training. Natick: US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine Technical Report Number T00–13; 2000.

Nana A, Slater GJ, Stewart AD, Burke LM. Methodological review: using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) for the assessment of body composition in athletes and active people. Int J Sports Nutr Exerc Metabol. 2014;24:196–215.

Knapik JJ, Montain SJ, McGraw SM, Grier T, Ely MR, Jones BH. Risk factors for stress fractures in basic combat training. Int J Sports Med. 2012;33:940–6.

Holiday DB, Ballard JE, Mckeown BC. PRESS-related statistics: regression tools for cross-validation and case diagnostics. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:612–20.

Cauley JA. Estrogen and bone health in men and women. Steroids. 2015;99:11–5.

Khosla S, Oursler MJ, Monroe DG. Estrogens and the skeleton. Trends Endrocriol Metab. 2012;23(11):576–81.

Li J, Papadopoulos V, Vihma V. Steroid biosynthesis in adipose tissue. Steroids. 2015;103:89–104.

Chumlea WC, Wisemandle W, Guo SS, Siervogel RM. Relations between frame size and body composition and bone mineral status. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;75:1012–6.

Trotter M, Broman GE, Peterson RR. Densities on bones of white and negro skeletons. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1960;42A:50–8.

Bachrach LK, Hastie T, Wang MC, Narssimhan R, Marcus R. Bone mineral acquisition in healthy Asian, hispanic, black and caucasian youth: a longitudinal study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:4702–12.

Nelson DA, Barondess DA, Hendrix SL, Beck TJ. Cross-sectional geometry, bone strength, and bone mass in the proximal femur in black and white postmenopausal women. J Bone Mineral Metabol. 2000;15:1992–7.

Ettinger B, Sidney S, Cummings SR, Libanati C, Bikle DD, Tekawa IS, Tolan K, Steiger P. Racial differences in bone mineral density between young adult black and white subjects persist after adjustment for anthropometric, lifestyle, and biochemical differences. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:429–34.

Knapik JJ, Sharp MA, Canham-Chervak M, Hauret K, Patton JF, Jones BH. Risk factors for training-related injuries among men and women in basic combat training. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001;33:946–54.

Jackson AS, Pollock ML, Ward A. Generalized equations for predicting body density of women. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1980;12:175–82.

Jackson AS, Pollock ML. Generalized equations for predicting body density of men. Brit J Nutr. 1978;40:497–504.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Angie Cost from the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch of the Defense Health Agency for providing us with the 11-year recruit data for analyses.

Funding

This study used internal funding from the US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine.

Availability of data and materials

Datasets used and analyzed during the current study may be available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JJK conceived the study, compiled and analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. SJM and MAS assisted in conceiving the study, collected the data, and assisted in manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Authors’ information

The views, opinions, and/or findings contained in this report are those of the author(s) and should not be construed as an official Department of the Army position, policy, or decision, unless so designated by other official documentation. In the conduct of research involving human subjects, the investigator(s) adhered to the policies regarding the protection of human subjects as prescribed by Department of Defense Instruction 3216.02 (Protection of Human Subjects and Adherence to Ethical Standards in DoD-Supported Research) dated 8 November 2011.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval for this investigation was provided by the Human Subjects Protection Office of the US Army Research Institute of Environmental Medicine after reviewing the research protocol. This was a secondary analysis of data for which written consent was obtained from participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Knapik, J.J., Sharp, M.A. & Montain, S.J. Association between stress fracture incidence and predicted body fat in United States Army Basic Combat Training recruits. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 19, 161 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2061-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-018-2061-3