Abstract

Background

Arthritis is a gendered disease where women have a higher prevalence and more disability than men with arthritis of the same age. Health survey data is a major source of information for monitoring of the burden of arthritis. The validity of self-reported arthritis and the determinants of its accuracy among women have not been thoroughly studied. The objectives of this study were to: 1) examine the agreement between self-report diagnosed arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms in community-living older women; 2) estimate the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of self-reported arthritis; and 3) assess the factors associated with the disagreement.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey of women was undertaken in 2012–13. The health survey asked women about diagnosed arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms. Agreement between self-reported arthritis and musculoskeletal signs symptoms was measured by Cohen’s kappa. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values of self-reported arthritis were estimated using musculoskeletal signs and symptoms as the reference standard. Factors associated with disagreement between self-reported arthritis and the reference standard were examined using multiple logistic regression.

Results

There were 223 participants self-reported arthritis and 347 did not. A greater number of participants who self-reported arthritis were obese compared to those who did not report arthritis. Those who reported arthritis had worse health, physical functioning, and arthritis symptom measures. Among the 570 participants, 198 had musculoskeletal signs and symptoms suggesting arthritis (the reference standard). Agreement between self-reported arthritis and the reference standard was moderate (kappa = 0.41). Sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive values of self-reported arthritis in older women were 66.7, 75.5, 59.2, and 81.0% respectively. Regression analysis results indicated that false-positive is associated with better health measured by the Short Form 36 physical summary score, the Health Assessment Questionnaire disability index, or the Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index total score; whereas false-negative is negatively associated with these variables.

Conclusion

While some women who reported diagnosed arthritis did not have recent musculoskeletal signs or symptoms, others with the signs and symptoms did not report diagnosed arthritis. Researchers should use caution when employing self-reported arthritis as the case-definition in epidemiological studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Arthritis is very common and a leading cause of pain and disability around the world [1–3]. A considerable amount of healthcare resources is dedicated by the governments to the management of arthritis [1, 4–6]. It is estimated that over 50 million people are living with arthritis in the USA [4], while over 10 million and three million people are affected by the disease in the UK and Australia respectively [1, 7]. Arthritis is also a gendered disease, where women are more likely to be affected than men [1, 3–5, 8]. For example, osteoarthritis (i.e. the most common form of arthritis) affects women more severely and at more sites [8–10]. Consequently, women with arthritis account for more healthcare utilisation than do men with arthritis at the same age [6, 9, 11]. The rate of joint replacements (knee replacements particularly) performed in women is also much higher than that for men, reflecting both the higher prevalence and the worse severity of arthritis in women [9, 11]. As managing arthritis poses a considerable challenge to the limited resources in the healthcare systems and affects the quality of life of millions of women, it is important to monitor the burden of arthritis.

Self-report heath survey data is a major source of information for epidemiological studies and other health research [12, 13]. Use of self-reported health data is feasible because health survey data are often routinely collected by government departments and/or agencies (especially in developed countries) and are readily available and accessible [12–14]. Self-reported diagnosed arthritis is among the most commonly used case-definition for prevalence and other epidemiological studies of arthritis burden [15–25]. Although it has been argued that self-reported diagnosis of chronic conditions may suffer from recall-bias, which could lead to underreporting of conditions and underestimation of prevalence [15, 26–28], some researchers have justified the use of self-reported arthritis as it has good agreement with medical records [18–20], and an adequate level of sensitivity and specificity in previous validation studies [22]. However, it is acknowledged that generalization of the findings of validation studies from one population to another may be inappropriate due to the differences in socio-demographic, lifestyle, and health characteristics which may affect the willingness of individuals to report medical conditions and/or seek healthcare [21–25]. For example, there is evidence indicating women tend to overreport (i.e. instead of underreport) arthritis in health survey compared to men [29]. Nonetheless, previous validation studies of self-reported arthritis have mostly been based on a non-gender specific sample and/or have not performed stratified analysis by gender [30–33]. Since women are most at risk of arthritis, a study with a particular focus on women represents an important step to the better understanding of the validity of self-reported arthritis and its application in large epidemiological studies.

The objective of this study is to examine the accuracy of self-reported arthritis as the case-definition in community-living women for the epidemiological study of arthritis. The specific aims are threefold: 1) to assess the agreement between self-reported diagnosed arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms suggesting arthritis in older women; 2) to assess the accuracy of self-reported arthritis based on the sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values using musculoskeletal signs and symptoms as the reference; and 3) to examine the factors associated with disagreement between self-reported arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms.

Methods

Participants

The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH) is a population-based survey of women that began in 1996 [34]. ALSWH participants were randomly selected from the national health insurance database [35]; they broadly represented the women in Australia at that time [36]. ALSWH is designed to investigate multiple factors that affect the health and well-being of women [35]. Since arthritis is a gendered disease and women are particularly at risk [1, 3–6, 8, 9], ALSWH provided an appropriate sampling frame for this study.

Data collection

A cross-sectional survey of a sample of women from the 1946–51 birth cohort of ALSWH was undertaken between December 2012 and March 2013. Postal self-administered questionnaires were sent to 350 randomly selected women who previously self-reported arthritis in Survey 3 (2001) and/or Survey 4 (2004), and another 350 women who had never reported arthritis in the ASLWH. Reminder leaflets were sent to non-respondents 30 days after the initial mail-out. Details of the protocol for this health survey have been published [37].

Self-reported diagnosed arthritis

In the survey questionnaire, participants were asked: “In the past 3 years, have you been diagnosed or treated for (a list of conditions)?” The forms of arthritis listed were osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, psoriatic arthritis, gout, and/or other form of arthritis. Self-reported diagnosed arthritis in the present study was defined as an answer of “Yes” to any form of arthritis.

Reference standard for arthritis

The reference standard definition of arthritis was based on the reported musculoskeletal signs and symptoms suggesting arthritis. A set of musculoskeletal signs and symptom questions were adapted from the Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Disease (COPCORD) Core Questionnaire (CCQ) [38]. The COPCORD-CCQ was originally designed by the WHO and the International League against Rheumatism (ILAR) as a screening tool for rheumatic symptoms and disabilities in the community [39]. COPCORD-CCQ has been applied to study the prevalence of rheumatic diseases among community-living individuals in Australia, [40] and other countries [38]. The CCQ has established high validity as rheumatic disease screening and diagnostic tools [41, 42]. Simplified versions of COPCORD type questionnaires have been proposed [42, 43], and four variables (i.e. pain in the last 7 days, high pain score, a Health Assessment Questionnaire score of greater than 0.80, and previous diagnosis) have been shown to perform well in the identification of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis cases in the community [43]. While another study has demonstrated that two questions: 1) “In the last 7 days (or ever) have you had any problem, that is pain, tenderness (pain on pressure), swelling or stiffness in your bones, joints and muscles?” and responding “Yes”; and 2) “Was there a traumatic event (such as strain or injury) that caused the pain, tenderness, swelling or stiffness?” and responding “No”; can be used to detect rheumatic disorders such as arthritis in the general population [42]. Thus, the reference case-definition of arthritis in the present study was defined as: 1) reported pain, tenderness, swelling or stiffness in bones, joints or muscles in the last week; 2) that this pain was not caused by a traumatic event; and 3) that the pain was at least mild in severity (i.e. level three or greater on the 0–10 scale). Confirmation of diagnosis based on signs and symptoms that include joint pain, tenderness, swelling, stiffness and reduced mobility also aligns with the recommendations made by the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP) about the clinical examination of osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis [44, 45].

Socio-demographic, lifestyle, and health variables

To describe characteristics of the sample, socio-demographic, lifestyle, and health variables were used. Inclusion of these variables was guided by the literature, where variables that were shown to be associated with arthritis or false-reporting of arthritis were included [22, 29–31, 33, 46]. The socio-demographic variables included were age, marital status, area of residence, and level of education. The lifestyle variables were current smoking status and obesity. Obesity was defined as a body mass index (BMI) equal to or greater than 30, i.e. according to the WHO criteria [47]. The health variables were the Short Form 36 (SF-36) quality of life measures [48], the Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) disability index [49], the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) [50], and a list of chronic conditions that are common in older women. The SF-36 measures included the physical (PCS) and mental (MCS) component summary scores, which range from 0 to 100, and higher scores represent better health [48]. The HAQ disability index assesses functional ability in eight categories including dressing, rising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip, and usual activities [49]. The WOMAC was developed to measure symptoms and physical disability for individuals with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee, and evaluates pain, stiffness, and physical functions, where higher score represents worse symptoms [50]. The list of chronic conditions included anxiety, asthma, bronchitis/emphysema, depression, diabetes, heart disease, hypertension, low iron levels, osteoporosis, and thrombosis.

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the participants who self-reported diagnosed arthritis and those who did not report arthritis in the survey questionnaire were compared using t-tests (for normally distributed continuous variables), Wilcoxon Mann–Whitney tests (for non-normally distributed continuous variables), and chi-square tests (for categorical variables) [51]. A priori two-tailed α level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests.

Agreement between self-reported diagnosed arthritis and the reference standard was measured by Cohen’s kappa (κ), which is a chance adjusted measure of agreement [52]. Sensitivity, specificity, and the predictive values of self-reported arthritis were also estimated. For this study, a true-positive was defined as a case identified by both self-reported arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms, whereas a false-positive was defined as a case identified by self-reported arthritis but not ascertained by the reference standard.

Logistic regression was used to assess the characteristics of women associated with disagreement between self-reported arthritis and the reference standard, with separate models for: 1) false-positives; and 2) false-negatives. The lifestyle and health variables were of particular relevance. Overweight and obesity have been linked to arthritis [8], and individuals who are obese has been shown to be associated with overreporting of arthritis [31]. Health variables including PCS and the number of activities of daily living (ADL) limitations have been linked to false-reporting of arthritis [30, 31]. However, the directions of association have not been consistent. For example, in one report, self-related health was found to be negatively associated with overreporting of arthritis [31]; whereas in another report, physical health was found to be positively associated with overreporting [30]. In another study, better physical health was identified as a factor also positively associated with underreporting while ADL limitations (i.e. can be linked to worse physical health) was found to be a significant factor of underreporting [30]. In the current study, both SF-36 PCS and MCS measures, the HAQ, WOMAC total score, and comorbidity were included in the analysis. Comorbidity was a count of chronic conditions listed above [30]. However, health measures may be strongly correlated to each other. To avoid multicollinearity in the multivariable regression models, correlations of the health variables were assessed in the preliminary analysis (see below).

Potential explanatory variables for false-positive and false-negative were first examined using univariate analyses. Then, multivariable regression analyses were used to examine: a) the effects of the lifestyle variables after controlling for the socio-demographics, and b) the effect of health variables after controlling for both socio-demographic and lifestyle variables. Preliminary analysis indicated that the SF-36 PCS, HAQ, and WOMAC are strongly correlated (correlation coefficients >0.75). Hence, four multivariable regression models (a-d) were constructed for false-positive and false-negative. The models were those included: a) the socio-demographic and lifestyle variables only; b) the socio-demographics, lifestyle variables, comorbidity, and the SF-36 summary scores; c) the socio-demographics, lifestyle variables, comorbidity, and HAQ; and d) the socio-demographics, lifestyle variables, comorbidity, and the WOMAC score. Statistical analyses were performed in Stata IC version 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

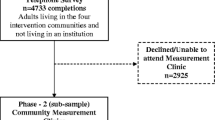

As at 22nd March 2013, 574 women had completed and returned the survey questionnaire; the response rate was 82.0%. Among them, 570 women answered the sign and symptom questions. Analysis was based on data from these 570 women (i.e. 81.4% of the 700 women originally approached). The flow from the recruitment stage to the classification of women is illustrated in Fig. 1. Overall, women with and without self-reported diagnosed arthritis are not significantly different in socio-demographic characteristics; but an increased proportion were obese, had more chronic conditions, worse quality of life (PCS and MCS), greater disability, and worse in the WOMAC total score compared to women without arthritis. Listed in Table 1 are the characteristics of the sample.

Crude prevalence of arthritis estimates based on self-reported arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms were not statistically significantly different; they were 39.1% (95% CI 35.1–43.3%) and 34.7% (95% CI 30.8–38.8%) respectively. The number of cases identified uniquely by either of the definitions and both case-definitions concurrently is depicted in the Venn diagram (Fig. 2). Agreement between self-reported arthritis and musculoskeletal symptoms was moderate (κ = 0.41, 95% CI 0.33–0.49). Sensitivity of self-reported arthritis was 66.7% (95% CI 60.0–73.3%), whereas specificity was 75.5% (95% CI 71.1–79.9%). Positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive values (NPV) of self-reported arthritis were 59.2% (95% CI 52.7–65.7%) and 81.0% (95% CI 76.8–85.1%) respectively. The contingency table is exhibited in Table 2.

An illustration of the number of cases identified by the two definitions among older women. Self-reported diagnosed arthritis identified 223 (=91 + 132) cases and 198 (=132 + 66) cases were confirmed using on musculoskeletal (MSK) signs and symptoms. There were 132 common cases identified by both definitions

When using musculoskeletal signs and symptoms as the reference standard, univariate analysis results indicated that false-positiveness of self-reported arthritis was associated with a higher level of education, being obese, or better physical health; and negatively associated with disability or a higher WOMAC score. They also indicated that false-negatives were associated obesity, disability or the WOMAC score; but negatively associated with physical health. Details of the univariate analysis results can be found in an additional file [see Additional file 1: Table S1].

Results of the multiple logistic regression models are illustrated in Tables 3 and 4. In Table 3, results show that after controlling for the socio-demographics, lifestyle variables including obesity were not significant predictors of false-positive (Model 1a). When controlling for both socio-demographic and lifestyle variables, better physical health (P < 0.001), a lower disability measure (P = 0.001) or WOMAC score (P = 0.003) is significantly associated with false-positive (Models 1b – 1d). Obesity is significantly associated with false-negative (P = 0.045) after controlling for socio-demographics (Model 2a in Table 4). However, when the health variables were simultaneously entered into the models, only comorbidity (P = 0.037) and physical health (P < 0.001, Model 2b), or greater disability (P < 0.001, Model 2c), or greater WOMAC scores (P = 0.001, Model 2d) were associated with false-negative.

Discussion

This study compared self-reported diagnosed arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms suggesting arthritis in a sample of geographically diverse older Australian women. Prevalence estimates based on the two case-definitions of arthritis were not statistically significantly different, but Cohen’s kappa shows that their agreement was only moderate. While two-fifths (91/223) of the self-reported arthritis cases did not have musculoskeletal signs and symptoms, two-thirds (132/198) of cases identified by signs and symptoms also reported diagnosed arthritis. Although it has been suggested that women are more likely to consult a doctor for their conditions and lead to an increased chance of diagnoses [22], our results indicate there were some women in our sample who had joint signs and symptoms (suggesting arthritis) have not had a diagnosis of arthritis. Possible contributing factors to this finding may include cultural beliefs and awareness of arthritis. Some individuals may have believed joint signs and symptoms are an inevitable result of ageing and hence did not seek help from their doctor [10], despite the fact that the effects of arthritis can be reduced through early treatment and appropriate management.

Our results also indicate that self-reported diagnosed arthritis has moderate sensitivity and specificity when using musculoskeletal signs and symptoms as the reference standard. These results are somewhat different to those in previous studies that included both women and men [31, 53]. One USA study involving an older sample from Georgia and using rheumatologists’ summary assessment as the reference standard, found that self-reported arthritis had substantial agreement with the reference standard [31]. Another study with a similar methodology found that self-reported arthritis had high sensitivity and moderate specificity in a population aged 65 or older living in Massachusetts [53]. Aside from the sample differences between the studies, the agreement and other performance measures in the current study might have been underestimated due to our adoption of the COPCORD questions. We did not use rheumatologist’s diagnosis because we do not think it is an appropriate case-definition of arthritis in the community. In Australia, general practitioners are the first point of contact for people with arthritis [1]. The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners recommends that confirmation of a diagnosis of osteoarthritis (i.e. far more common than any other form of arthritis) should be based on clinical presentations such as joint pain, swelling, stiffness and reduced mobility [44]. This is consistent with our first question, which assessed musculoskeletal signs and symptoms that include pain, tenderness, swelling or stiffness in the joints, bones, and muscles. However, our adoption of the COPCORD-CCQ also means we assessed only the signs and symptoms “in the last week” [42]. This is where it is incompatible with the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners guidelines. In the guideline for the general practitioners, there is a lack of specification of the timeframe of the signs and symptoms being assessed [44].

The timeframe in the COPCORD questions is similar to that in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) criteria for diagnosing osteoarthritis of the hip or knee, which examine case-ness based on joint pain experienced “on most days of the past month” [54, 55]. Both the COPCORD-CCQ and the ACR criteria require regular and frequent musculoskeletal symptoms for diagnosis. Yet, this definition may have been too restrictive for monitoring the burden of arthritis in community-living individuals [32]. It has been suggested that case-definitions that require frequent musculoskeletal symptoms can omit cases that have fluctuating symptoms, or whose symptoms (and/or signs) are controlled by regular medication [32]. Instead, questions about signs and symptoms “in the previous 6 months” [32], and/or a question about the use of arthritis-related medicines [29, 53], may better detect arthritis in the community. If we had used the above questions, then the reference standard would have included more cases, and the number of true-positives would have been higher and the number of false-negatives would have been lower. This would have a positive impact on the estimated agreement and the four performance measures (i.e. sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV) in our study.

Our results from the multiple regression models shed light to the possible reasons for disagreement between self-reported arthritis and reference standard. Recall that the results indicate better SF-36 physical component, and lower disability or WOMAC scores are associated with false-positive; while, obesity, lower PCS, and greater disability or WOMAC scores are associated with false-negative. Previously, Bombard et al. (2005) suggested that individuals with better health have better control of their conditions, making them less likely to report their musculoskeletal signs and symptoms [31]. Conversely, individuals with worse health are more aware of their signs and symptoms and more likely to report them [31]. Thus, women who had arthritis but had otherwise good health were less likely to report any sign and symptom and be classified as false-positive, whereas women who did not have arthritis but had worse overall health were more likely to report their musculoskeletal signs and symptoms and be classified as false-negative.

There are both limitations and strengths to this study. First, our reference standard is not the gold-standard case-definition of arthritis for epidemiological studies. A gold-standard case-definition of arthritis for epidemiological research does not exist [30, 56]. Our choice was based on: a) it allowed us to measure the agreement with clinical signs and symptoms instead of, for example, radiographic evidence which may not link to symptoms or treatment decisions [44]; b) the assessed musculoskeletal signs and symptoms aligned with those recommended in the general practitioner’s guidelines for the diagnosis of arthritis [44]; and c) COPCORD questions have been used to estimate the burden of musculoskeletal conditions in community-living individuals in Australia [40]. Second, our study did not include men. It has been reported that factors associated with the reporting of joint symptoms are different between women and men [57]. Hence, our results might not be generalizable to the male population. However, the present sample was specifically chosen because the research focus of this study was the accuracy of self-reported arthritis in older women. Arthritis is a gendered disease where women have a higher prevalence [1, 3, 5], and more disabilities [3, 9, 10]. This study provides important information about the accuracy of self-reported diagnosed arthritis in a population most affected by arthritis (i.e. older women). Concurrently, our sample represents a strength of this study because: a) survey participants were randomly drawn from an ALSWH cohort which is geographically diverse [36]; and b) the response rate in this study was very high. These factors contribute positively to both the external and internal validity of the findings.

Conclusion

Self-reported arthritis is one of the most common case-definitions in epidemiological studies. Our results show that the estimated prevalence of arthritis in older community-living women based on self-reported diagnosed arthritis and cases identified by musculoskeletal signs and symptoms were not statistically significantly different. However, our results also show that agreement between self-report diagnosed arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms was only moderate. Results indicate two-fifths of self-reported arthritis did not have musculoskeletal signs and symptoms in the previous week (false-positives), while one-third of cases identified by signs and symptoms did not report diagnosed arthritis (false-negatives). These findings may suggest that a combined case-definition that includes both reported arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms be more effectively capture the diagnosed cases that could have fluctuating symptoms as well as the individuals who have the signs and symptoms but have not received a diagnosis; the feasibility and validity of such hybrid case-definition should be examined in future studies. Regression analysis did not find any significant socio-demographic factor or lifestyle factor associated with disagreement once the health variables were included. The results indicate that better general physical health is associated with a false-positive while worse overall health is associated with a false-negative. Researchers who use self-reported diagnosed arthritis as the case-definition should consider these limitations when making interpretation of results and drawing conclusions.

Abbreviations

- ACR:

-

American College of Rheumatology

- ALSWH:

-

The Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CCQ:

-

Core Questionnaire

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- COPCORD:

-

Community Oriented Program for Control of Rheumatic Disease

- HAQ:

-

Health Assessment Questionnaire

- ILAR:

-

International League against Rheumatism

- MCS:

-

The SF-36 mental component summary

- MSK:

-

Musculoskeletal

- NPV:

-

Negative predictive value

- PCS:

-

The SF-36 physical component summary

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- RACGP:

-

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SF-36:

-

Short Form 36

- WHO:

-

The World Health Organization

- WOMAC:

-

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

References

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). A snapshot of arthritis in Australia 2010. Canberra: AIHW; 2010. Arthritis series no. 13. Cat. no. PHE 126.

Mariller MM, Santos-Eggimann B. The prevalence of rheumatic diseases in the elderly in developed countries and its evolution over time. Soz Praventivmed. 2005;50(1):45–51.

Theis KA, Helmick CG, Hootman JM. Arthritis burden and impact are greater among U.S. women than men: intervention opportunities. J Women's Health. 2007;16(4):441–53.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Arthritis-related statistics. 2014. http://www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/arthritis_related_stats.htm. Accessed 11 Oct 2014

Public Health Agency of Canada. Life with arthritis in Canada 2010. Canada: PHAC; 2010.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Use of health services for arthritis and osteoporosis. Canberra: AIWH; 2010. Arthritis series no. 14 Cat. no. PHE 130.

Arthritis Care. FAQs. 2014 https://www.arthritiscare.org.uk/what-is-arthritis/faqs/arthritis. Accessed 11 Oct 2014.

Gariepy G, Rossignol M, Lippman A. Characteristics of subjects self-reporting arthritis in a population health survey: distinguishing between types of arthritis. Can J Public Health. 2009;100(6):467–71.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Arthritis and osteporosis in Australia 2008. Canberra: AIHW; 2008. Arthritis series no. 8. Cat. no. PHE 106.

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). A picture of osteoarthritis in Australia. Canberra: AIHW; 2007. Arthritis series no. 5. Cat. no. PHE 93.

Rolfson O, Strom O, Karrholm J, Malchau H, Garellick G. Costs related to hip disease in patients eligible for total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1261–6.

Centers for Disease Control Prevention (CDC). About the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). 2013. http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/about/about_brfss.htm. Accessed 2 Apr 2014

Beland Y. Canadian community health survey–methodological overview. Health Rep. 2002;13(3):9–14.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. National Health Survey: User’s Guide. 2009. http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/ProductsbyReleaseDate/2851D0FD9C52AB56CA257ACC000E3DE1?OpenDocument. Accessed 7 Jan 2015

Busija L, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH. Quantifying the impact of transient joint symptoms, chronic joint symptoms, and arthritis: a population-based approach. Arthritis Care Res. 2009;61(10):1312–21.

Badley EM, Ansari H. Arthritis and arthritis-attributable activity limitations in the United States and Canada: a cross-border comparison. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010;62(3):308–15.

Dominick KL, Golightly YM, Jackson GL. Arthritis prevalence and symptoms among US non-veterans, veterans, and veterans receiving Department of Veterans Affairs Healthcare. J Rheumatol. 2006;33(2):348–54.

Stang PE, Brandenburg NA, Lane MC, Merikangas KR, Von Korff MR, Kessler RC. Mental and physical comorbid conditions and days in role among persons with arthritis. Psychosom Med. 2006;68(1):152–8.

van’t Land H, Verdurmen J, Ten Have M, van Dorsselaer S, Beekman A, de Graaf R. The association between arthritis and psychiatric disorders; results from a longitudinal population-based study. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68(2):187–93.

Globe DR, Varma R, Torres M, Wu J, Klein R, Azen SP. Self-reported comorbidities and visual function in a population-based study: the Los Angeles Latino Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123(6):815–21.

Ferucci ED, Schumacher MC, Lanier AP, Murtaugh MA, Edwards S, Helzer LJ, et al. Arthritis prevalence and associations in American Indian and Alaska native people. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59(8):1128–36.

Busija L, Hollingsworth B, Buchbinder R, Osborne RH. Role of age, sex, and obesity in the higher prevalence of arthritis among lower socioeconomic groups: a population-based survey. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(4):553–61.

Lee S, Tsang A, Huang Y-Q, Zhang M-Y, Liu Z-R, He Y-L, et al. Arthritis and physical-mental comorbidity in metropolitan China. J Psychosom Res. 2007;63(1):1–7.

Vuković D, Bjegović V, Vuković G. Prevalence of chronic diseases according to socioeconomic status measured by wealth index: health survey in Serbia. Croat Med J. 2008;49(6):832–41.

Lima MG, De Azevedo Barros MB, César CLG, Goldbaum M, Carandina L, Ciconelli RM. Impact of chronic disease on quality of life among the elderly in the state of Sao Paulo, Brazil: a population-based study. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2009;25(4):314–21.

Balluz LS, Okoro CA, Mokdad A. Association between selected unhealthy lifestyle factors, body mass index, and chronic health conditions among individuals 50 years of age or older, by race/ethnicity. Ethn Dis. 2008;18(4):450–7.

Ng TP, Niti M, Chiam PC, Kua EH. Prevalence and correlates of functional disability in multiethnic elderly Singaporeans. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(1):21–9.

Niti M, Ng TP, Kua EH, Ho RCM, Tan CH. Depression and chronic medical illnesses in asian older adults: the role of subjective health and functional status. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(11):1087–94.

Kriegsman DM, Penninx BW, van Eijk JT, Boeke AJ, Deeg DJ. Self-reports and general practitioner information on the presence of chronic diseases in community dwelling elderly. A study on the accuracy of patients’ self-reports and on determinants of inaccuracy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1407–17.

Singh JA. Discordance between self-report of physician diagnosis and administrative database diagnosis of arthritis and its predictors. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(9):2000–8.

Bombard JM, Powell KE, Martin LM, Helmick CG, Wilson WH. Validity and reliability of self-reported arthritis: Georgia senior centers, 2000–2001. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(3):251–8.

March LM, Schwarz JM, Carfrae BH, Bagge E. Clinical validation of self-reported osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1998;6(2):87–93.

Kvien TK, Glennas A, Knudsrod OG, Smedstad LM. The validity of self-reported diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis: results from a population survey followed by clinical examinations. J Rheumatol. 1996;23(11):1866–71.

Women’s Health Australia. Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health: Study overview. 2013. http://www.alswh.org.au/. Accessed: 21 Mar 2013

Brown WJ, Bryson L, Byles J, Dobson A, Manderson L, Schofield M, et al. Women’s health Australia: establishment of the Australian longitudinal study on women’s health. J Women's Health. 1996;5(5):467–72.

Brown WJ, Dobson AJ, Bryson L, Byles JE. Women’s Health Australia: on the progress of the main cohort studies. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 1999;8(5):681–8.

de Luca K, Parkinson L, Byles J. A study protocol for the profile of pain in older women: assessing the multi dimensional nature of the experience of pain in arthritis. Chiropr Man Therap. 2014;22(1):1–7.

Chopra A. COPCORD – an unrecognized fountainhead of community rheumatology in developing countries. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(12):2320–2.

Chopra A, Patil J, Billempelly V, Relwani J, Tandle HS. Rheumatology Community Oriented Program from Control of R, Diseases: prevalence of rheumatic diseases in a rural population in western India: a WHO-ILAR COPCORD Study. J Assoc Physicians India. 2001;49:240–6.

Minaur N, Sawyers S, Parker J, Darmawan J. Rheumatic disease in an Australian Aboriginal community in North Queensland, Australia. A WHO-ILAR COPCORD survey. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(5):965–72.

Al-Awadhi A, Olusi S, Moussa M, Al-Zaid N, Shehab D, Al-Herz A, et al. Validation of the Arabic version of the WHO-ILAR COPCORD Core Questionnaire for community screening of rheumatic diseases in Kuwaitis. World Health Organization. International League Against Rheumatism. Community Oriented Program for the Control of Rheumatic Diseases. J Rheumatol. 2002;29(8):1754–9.

Bennett K, Cardiel MH, Ferraz MB, Riedemann P, Goldsmith CH, Tugwell P. Community screening for rheumatic disorder: cross cultural adaptation and screening characteristics of the COPCORD Core Questionnaire in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. The PANLAR-COPCORD Working Group. Pan American League of Associations for Rheumatology. Community Oriented Programme for the Control of Rheumatic Disease. J Rheumatol. 1997;24(1):160–8.

Goycochea-Robles MV, Sanin LH, Moreno-Montoya J, Alvarez-Nemegyei J, Burgos-Vargas R, Garza-Elizondo M, et al. Validity of the COPCORD Core Questionnaire as a classification tool for rheumatic diseases. J Rheumatol. 2011;38 Suppl 86:31–5.

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners. Guideline for the non-surgical management of hip and knee osteoarthritis. Melbourne; 2009

The Royal College of General Practitioners. Clinical guideline for the diagnosis and management of early rheumatoid arthritis. Melbourne; 2009

Wright NC, Riggs GK, Lisse JR, Chen Z. Self-reported osteoarthritis, ethnicity, body mass index, and other associated risk factors in postmenopausal women - results from the women’s health initiative. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(9):1736–43.

World Health Organization. BMI classification. 2012. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/. Accessed 14 Dec 2014

Ware Jr JE. SF-36 Health Survey update. Spine. 2000;25(24):3130–9.

Bruce B, Fries JF. The Stanford health assessment questionnaire: dimensions and practical applications. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2003;1(1):20.

McConnell S, Kolopack P, Davis AM. The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC): a review of its utility and measurement properties. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;45(5):453–61.

Institute for Digital Research and Education (idre). What statistical analysis should I use? Statistical analyses using Stata. UCLA; 2013. http://www.ats.ucla.edu/stat/stata/whatstat/whatstat.htm. Accessed 6 Feb 2013

Viera AJ, Garrett JM. Understanding interobserver agreement: the kappa statistic. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):360–3.

Sacks JJ, Harrold LR, Helmick CG, Gurwitz JH, Emani S, Yood RA. Validation of a surveillance case definition for arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2005;32(2):340–7.

Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, Bole G, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Classification of osteoarthritis of the knee. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Criteria Committee of the American Rheumatism Association. Arthritis Rheum. 1986;29(8):1039–49.

Altman R, Alarcon G, Appelrouth D, Bloch D, Borenstein D, Brandt K, et al. The American College of Rheumatology criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis of the hip. Arthritis Rheum. 1991;34(5):505–14.

Rasooly I, Papageorgiou AC, Badley EM. Comparison of clinical and self reported diagnosis for rheumatology outpatients. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995;54(10):850–2.

Charles ST, Gatz M, Pedersen NL, Dahlberg L. Genetic and behavioral risk factors for self-reported joint pain among a population-based sample of Swedish twins. Health Psychol. 1999;18(6):644.

Acknowledgments

The research on which this paper is based was conducted as part of the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health (ALSWH), the University of Newcastle and the University of Queensland. We are grateful to the Australian Government Department of Health for support and to the women who provided the survey data. This research was also supported by infrastructure and staff of the Research Centre for Gender, Health and Ageing, who are members of the Hunter Medical Research Institute. Dr. Katie de Luca is acknowledged for her contribution towards the design and administration of the Profile of Pain in Older Women health survey.

Funding

The Profile of Pain in Older Women with Arthritis substudy was funded by the 2011 Hunter Medical Research Institute (HMRI) Lions Club of Adamstown Research Project Grant (No. G1200432). TL was supported by the University of Newcastle International Postgraduate Research Scholarship and the University of Newcastle Research Scholarship Central student scholarship.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and/or analysed during the current study can be made available upon approval of a formal request from the PSA Committee of ALSWH and substudy investigators. For more information, please refer to: http://www.alswh.org.au/for-researchers/sensitive-data-sharing.

Authors’ contributions

TL, LP, MC, and JB were involved in the study design, interpretation of the results and revising the paper critically for intellectual content. TL constructed the datasets, conducted the statistical analyses, and drafted the paper. LP, MC, and JB supervised the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

ALSWH surveys have approval from the University of Newcastle and the University of Queensland Human Research Ethics Committees (HRECs) (Reference No. H0760795). Permission to use the ALSWH data was granted to the substudy investigators by the Publication, Analyses, and Substudies (PSA) Committee of ALSWH. Permission to conduct the Profile of Pain in Older Women with Arthritis substudy was granted by the PSA Committee of ALSWH (No. W079). Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Newcastle and the University of Queensland HRECs (Reference No. H-2012-0144). All participants provided written informed consent.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Univariate analysis results for factors associated with false-positive and false-negative. (DOCX 16 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Lo, T., Parkinson, L., Cunich, M. et al. Discordance between self-reported arthritis and musculoskeletal signs and symptoms in older women. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17, 494 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1349-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1349-4