Abstract

Background

A tenosynovial giant cell tumor (T-GCT) is a benign synovial tumor arising from the synovium, bursae, or tendon sheath. It can be intra- or extra-articular and localized or diffuse. Diffuse T-GCT is considered as a locally aggressive. Positron emission tomography (PET) with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose with computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) is widely used to differentiate malignant from benign tumors and to detect distant metastasis. However, FDG PET/CT is limited by false-positive findings. In this study, we present two cases of T-GCT that developed in unusual locations and were confused with malignant tumors. The final diagnoses were histologically confirmed as T-GCTs.

Case presentation

Case 1. A 45-year-old Japanese female presented with a left choroidal melanoma and an abnormal lesion adjacent to the first cervical (C1) lamina confirmed by a PET scan (maximum standardized uptake value [SUVmax] = 9.9 g/ml). MRI of the neck also detected a soft tissue mass (14.6 × 7.7 × 7 mm) adjacent to the C1 lamina. The choroidal melanoma was treated by heavy carbon ion radiotherapy. Although the size of the C1 soft tissue tumor remained unchanged, a CT-guided biopsy confirmed the diagnosis of the neck mass as a T-GCT.

Case 2. A 15-year-old Japanese male with multiple type 1 neurofibromatosis presented with a soft tissue mass (26.1 × 24.7 × 11.5 mm) of the extra-articular hip joint that was coincidentally detected by FDG PET/CT during examination of a mediastinal soft tissue mass. SUVmax of the mediastinal lesion was 2.6 g/ml and of the hip lesion was 12.8 g/ml. Thus, differentiation from a malignant tumor, such as a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, was necessary. An open biopsy was performed, and the frozen section was diagnosed as T-GCT. The tumor was excised, and the final histological diagnosis confirmed T-GCT.

Conclusion

T-GCT can show high FDG uptake, which might be confused with malignancy. Although MRI findings and location might help in the diagnosis of a T-GCT, careful assessment is mandatory, especially in unusual locations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

A tenosynovial giant cell tumor (T-GCT) is a benign, synovial tumor arising from the synovium, bursae, or tendon sheath. It can be intra- or extra-articular and localized or diffuse. A localized extra-articular T-GCT is synonymous with a giant cell tumor of the tendon sheath; it usually occurs in the hand (other sites include the wrist, ankle/foot, and knee) and is more often seen in women than men [1], with a reported annual incidence of about one in 50,000 [2]. Diffuse T-GCT is considered as a locally aggressive and predominantly involves the knee, followed by the hip, ankle, elbow, and shoulder [3]; it has a reported annual incidence of approximately two cases per million, mostly younger than 40 years of age, with no gender predilection [4]. Unusual sites of T-GCTs include extra-articular neck and hip [5, 6].

Positron emission tomography (PET) with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) with computed tomography (FDG PET/CT) is widely used to differentiate malignant from benign tumors and to detect distant metastasis [7, 8]. However, as on FDG is not cancer-specific, false-positive findings of benign diseases have been reported in active inflammation or infection [9–11]. Schulte et al. reported a 15 % false-positive rate of malignancy among 200 tumor and tumor-like lesions of the bone [12]. The appearance of T-GCT in FDG PET/CT was not fully reported because this modality is not routinely used. However, there are reports of varied FDG uptake (maximum standardized uptake value [SUVmax] = 3.43–25 g/ml) in T-GCTs, which mimic malignant tumors [13–16].

In this article, we discuss two cases of T-GCT that developed in unusual locations and were initially thought to be malignant tumors on FDG PET/CT, but were histologically confirmed as T-GCT.

Case presentation

Case 1

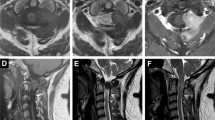

A 45-year-old Japanese woman presented with an abnormal lesion in her left eye (Fig. 1) in January 2015. FDG PET/CT detected mild FDG uptake in the left choroidal plexus lesion (SUVmax = 3.8 g/ml) and an intensely hypermetabolic extra-articular soft tissue density lesion adjacent to the first cervical (C1) lamina (SUVmax = 9.9 g/ml) (Fig. 2). N-isopropyl-p-123I-iodoamphetamine single-photon emission computed tomography showed high uptake in the left choroidal plexus lesion; thus, we arrived at a diagnosis of choroidal melanoma. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the neck detected a soft tissue mass (14.6 × 7.7 × 7 mm) adjacent to the C1 lamina, demonstrating an isointense signal on a T1-weighted image (WI), low signal on a T2WI, and enhanced gadolinium uptake (Fig. 3). She had no symptom related to the neck lesion. The choroidal melanoma was treated by heavy carbon ion radiotherapy from January to March 2015. The size of the soft tissue tumor of C1 remained unchanged, and we performed a CT-guided biopsy to confirm the diagnosis in mid-March 2015. Biopsy specimen showed small mononuclear stromal cells with stromal fibrosis, including formation of a hyalinized collagen matrix and a small area of multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells (Fig. 4a). Immunohistochemical analysis showed strong staining for CD68 (Fig. 4b). The final histological diagnosis was localized T-GCT. The tumor size remained stable for 6 months after biopsy, and no functional deficit was detected.

FDG PET/CT sagittal image (a) revealed two focal regions of increased uptake in the eye (white arrow) and posterior neck (black arrow). Axial image (b) showed increased FDG uptake in the eye (white arrow) and the choroid plexus of the left eye (SUVmax = 3.8 g/ml). Axial image (c) of the first cervical (C1) spine showed increased uptake (black arrow) adjacent to the C2 lamina (SUVmax = 9.9 g/ml)

Biopsy specimen showed small mononuclear stromal cells with stromal fibrosis, including formation of a hyalinized collagen matrix and a small area of multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells (hematoxylin and eosin staining; scale bar, 100 μm) (a). Immunohistochemical analysis showed strong staining for CD68 (b)

Case 2

A 15-year-old Japanese male was referred to our university hospital for evaluation of an abnormal lesion of the extra-articular hip joint in July 2015. He was previously diagnosed with multiple neurofibromatosis (neurofibromatosis type 1; NF-1) and had a history of cleft palate and hydronephrosis at the age of 7 years. A plain chest radiograph in 2014 had showed mediastinal widening. MRI revealed a soft tissue mass in the mediastinum. In May 2015, FDG PET/CT showed low FDG uptake (SUVmax = 2.6 g/ml) in the mediastinal mass and an intensely hypermetabolic extra-articular soft tissue density lesion in the left hip (SUVmax = 12.8 g/ml) (Fig. 5). MRI detected a soft tissue mass (26.1 × 24.7 × 11.5 mm) located along the proximal indirect tendon of the rectus femoris muscle, demonstrating isointense signals on T1- and T2WIs (Fig. 6). He had no symptom related to the hip soft tissue mass. Because of the previous diagnosis of NF-1, differentiation from a malignant tumor, such as a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor, was necessary. A percutaneous core needle biopsy was performed in June 2015 at the previous hospital, however the material was insufficient to define the diagnosis. An open biopsy was performed in July 2015, and the frozen section was diagnosed as T-GCT. Thus, we excised the tumor. Excised tumor specimen showed small mononuclear stromal cells and multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells (Fig. 7). The final histological diagnosis was localized T-GCT. He showed no functional deficit 2 months after the surgery.

Conclusions

T-GCT is a benign soft tissue tumor that arises from the synovium, bursae, or tendon sheath that typically contains areas of intermediate and/or low signal intensity on T1- and T2WIs. A T-GCT is usually diagnosed by MRI [17]. In our patients, the MRI findings were compatible with T-GCTs, even though the masses were located in unusual sites. Moreover, FDG PET/CT is not frequently employed for T-GCT, as the findings cannot be confirmed. Hamada et al. analyzed FDG PET/CT images of 56 soft tissue tumors (19 malignant and 37 benign tumors) and found statistically significant difference in the SUVmax between malignant and benign lesions in early scans (5.50 ± 5.32 g/ml versus 3.10 ± 2.64 g/ml). Moreover, the intensities of benign soft tissue lesions were <6.0 g/ml [18]. Broski et al. reported a mean SUVmax of 8.7 (range, 4.0–14.5) g/ml for FDG PET/CT imaging of 14 T-GCTs, and concluded that a T-GCT could be intensely hypermetabolic, mimicking musculoskeletal metastasis [15]. Selby et al. reported a pigmented villonodular synovitis of the shoulder mimicking a metastatic melanoma [16]. Lindkog et al. reported false-positive results of PDG PET/CT in five cases of benign soft tissue lesions, including two T-GCT lesions, and mentioned the importance of understanding the limitations of PET, including false-positive findings of benign lesions [11]. Hamada et al. reported a positive correlation of FDG SUVmax with the expression of GLUT-1 and hexokinase II in 49 musculoskeletal tumors [19]. However, the expression patterns of GLUT-1 and hexokinase II in T-GCTs have not been fully evaluated. Therefore, the mechanism of high uptake of FDG PET/CT in T-GCT remains uncertain. Although FDG PET/CT is a useful imaging modality for patients with a history of malignancy and the demand has been increasing, the chance of detecting benign lesions is also increased. When a T-GCT is detected in a typical location and MRI findings are compatible to T-GTC, careful observation without histological confirmation is reasonable. However, if a suspected T-GCT is detected in an unusual location, a biopsy should be performed for differentiation from a malignant tumor. Recently, there have been new developments in the medical treatment of T-GCT using a selective colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) kinase inhibitor [20]. FDG PET/CT might be a useful imaging modality in monitoring this treatment [21].

In conclusion, we encountered two cases of T-GCTs that developed in unusual locations, which were confused with malignant tumors. The final diagnoses of these cases were histologically confirmed as T-GCTs. It is important to realize that a T-GCT may show high FDG uptake, which can resemble from a malignant tumor. Although MRI findings and the location might help to diagnose a T-GCT, careful assessment is mandatory.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from Patient #1 and from the parents or legal guardians of Patient #2 for publication of these case reports and any accompanying images. Copies of the written consent forms are available for review from the Section Editor of this journal.

Availability of data and materials

All the data supporting our findings is contained within the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- T-GCT:

-

tenosynovial giant cell tumor

- FDG:

-

fluorodeoxyglucose

- PET:

-

positron emission tomography

- FDG PET/CT:

-

positron emission tomography with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose and computed tomography

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- SUVmax:

-

maximum standardized uptake value

- NF-1:

-

neurofibromatosis type 1

- CSF1R:

-

colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor

References

Jones FE, Soule EH, Coventry MB. Fibrous histiocytoma of synovium (giant cell tumour of tendon sheath, pigmented nodular synovitis). J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:76–86.

Monaghan H, Salter DM, Al-Nafussi A. Giant cell tumour of tendon sheath (localised nodular tenosynovitis): clinicopathological features of 71 cases. J Clin Pathol. 2001;54:404–7.

Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PCW, Mertens F. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone; World Health Organization; International Agency for Research on Cancer. 4th ed. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. p. 100–3.

de St. Aubain Somerhausen N, Dal Cin P. Diffuse-type giant cell tumour. In: Fletcher CDM, Unni KK, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and genetics of tumours of soft tissue and bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2002. p. 112–4.

Pillai G, Nicolas M, Lwin K, Pezzella F, Gatter K. An unusual presentation of diffuse tenosynovial giant cell tumour in the neck. Histopathology. 2003;43:393–6.

Rao AS, Vigorita VJ. Pigmented villonodular synovitis (giant-cell tumor of the tendon sheath and synovial membrane). A review of eighty-one cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:76–94.

Schrevens L, Lorent N, Dooms C, Vansteenkiste J. The role of PET scan in diagnosis, staging, and management of non-small cell lung cancer. Oncologist. 2004;9:633–43.

Lim HS, Yoon W, Chung TW, Kim JK, Park JG, Kang HK, et al. FDG PET/CT for the detection and evaluation of breast diseases: usefulness and limitations. Radiographics. 2007;27 Suppl 1:S197–213.

Goo JM, Im JG, Do KH, Yeo JS, Seo JB, Kim HY, et al. Pulmonary tuberculoma evaluated by means of FDG PET: findings in 10 cases. Radiology. 2000;216:117–21.

Kostakoglu L, Agress H, Goldsmith SJ. Clinical role of FDG PET in evalutaion of cancer patients. RadioGraphics. 2003;23:315–40.

Lindskog DM, Nikkhou K, Talusan P. False-positive positron emission tomography in patients with history of malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:e582–5.

Schulte M, Brecht-Krauss D, Heymer B, et al. Grading of tumors and tumorlike lesions of bone: Evaluation by FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 2000;41:1695–701.

Pallas A, Hagge R, Borys D, Hunter J. Intense FDG uptake in an intra-articular localized giant-cell tumor of the tendon sheath (pigmented villonodular synovitis) mimics metastatic melanoma. RCR. 2009;4:343.

Aoki J, Watanabe H, Shinozaki T, Takagishi K, Tokunaga M, Koyama Y, et al. FDG-PET for preoperative differential diagnosis between benign and malignant soft tissue masses. Skeletal Radiol. 2003;32:133–8.

Broski SM, Murdoch NM, Skinner JA, Wenger DE. Pigmented villonodular synovitis: potential pitfall on oncologic 18F-FDG PET/CT. Clin Nucl Med. 2015 Jul 7. [Epub ahead of print]

Selby L, Kukar M, Wang J, Beg M, Sullivan J. Pigmented villous nodular synovitis mimicking metastatic melanoma on PET-CT. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2014;5:231–3.

Jelinek JS, Kransdorf MJ, Utz JA, Berrey Jr BH, Thomson JD, Heekin RD, et al. Imaging of pigmented villonodular synovitis with emphasis on MR imaging. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1989;152:337–42.

Hamada K, Tomita Y, Ueda T, Enomoto K, Kakunaga S, Myoui A, et al. Evaluation of delayed 18 F-FDG PET in differential diagnosis for malignant soft-tissue tumors. Ann Nucl Med. 2006;20:671–5.

Hamada K, Tomita Y, Qiu Y, Zhang B, Ueda T, Myoui A, et al. 18 F-FDG-PET of musculoskeletal tumors: a correlation with the expression of glucose transporter 1 and hexokinase II. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22:699–705.

Tap WD, Wainberg ZA, Anthony SP, Ibrahim PN, Zhang C, Healey JH, et al. Structure-Guided Blockade of CSF1R Kinase in Tenosynovial Giant-Cell Tumor. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:428–37.

Cassier PA, Italiano A, Gomez-Roca CA, Le Tourneau C, Toulmonde M, Cannarile MA, et al. CSF1R inhibition with emactuzumab in locally advanced diffuse-type tenosynovial giant cell tumours of the soft tissue: a dose-escalation and dose-expansion phase 1 study. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:949–56.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hiroko Ikeda who helped to draft the manuscript. The authors also would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the English language review.

Funding

No funding has been received for this project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

No benefits in any form have been received or will be received from a commercial party directly or indirectly related to the subject of this article.

Authors’ contributions

AT was involved in data collection, case analysis, writing the manuscript, and performed the surgery and follow-up of Case 2. MT detected the T-GCT in Case 1 by FDG PET/CT. KF performed the needle biopsy of the T-GCT of Case 2. TO detected the T-GCT by FDG PET/CT in Case 2. NY, KH, and SM assisted in drafting the manuscript and reviewed the article. HT approved the final version of the paper. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Takeuchi, A., Yamamoto, N., Hayashi, K. et al. Tenosynovial giant cell tumors in unusual locations detected by positron emission tomography imaging confused with malignant tumors: report of two cases. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 17, 180 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1050-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12891-016-1050-7