Abstract

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a fatal progressive lung disease entailing significant impairment in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and high socioeconomic burden. The course of IPF includes episodes of acute exacerbations (AE-IPF) leading to poor outcomes. This study aimed to compare management, costs and HRQoL of patients with AE-IPF to patients without AE-IPF during one year in Spain.

Materials and methods

In a 12-month, prospective, observational, multicenter study of IPF patients, healthcare resource use was recorded and costs related to AE-IPF were estimated and compared between patients with and without AE-IPF. HRQoL was measured with the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), EuroQoL 5 dimensions 5 levels questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L), EQ-5D visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) and the Barthel Index.

Results

204 IPF patients were included: 22 (10.8%) experienced ≥ 1 acute exacerbation, and 182 (89.2%) did not. Patients with exacerbations required more primary care visits, nursing home visits, emergency visits, hospital admissions, pharmacological treatments and transport use (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Likewise, patients with exacerbations showed higher annual direct health AE-IPF-related costs. In particular, specialized visits, emergency visits, days of hospitalization, tests, palliative care, transport in ambulance and economic aid (p < 0.05 for all comparisons). Exploratory results showed that patients with AE-IPF reported a non-significant but substantial decline of HRQoL compared with patients without AE-IPF, although causality can be inferred.

Conclusion

We observed significantly higher resource use and cost consumption and lower HRQoL among patients suffering exacerbations during the study. Thus, preventing or avoiding AE-IPF is key in IPF management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a fatal, progressive fibrosing interstitial pneumonia of unknown cause characterized by progressive worsening of dyspnea, fibrosis and irreversible decline in lung function [1, 2].

IPF global prevalence ranges between 2 and 29 cases per 100,000 individuals [1], and may vary depending on the country. In Spain, it has an estimated prevalence of 13 cases per 100,000 in women and 20 per 100,000 in men, affecting a total of around 7,500 patients [3].

The clinical course of IPF is highly variable among patients, including slow/fast or stable progression patterns, and also episodes of acute exacerbations (AE-IPF) [4]. An AE-IPF is defined as an acute respiratory event, with or without an identifiable cause, which leads to a significant decline in lung function [5]. Suffering AE-IPF is associated with an important decline in forced vital capacity (FVC), almost 5-fold higher than in patients without exacerbations [6]. In turn, patients with a lower FVC at baseline are at higher risk of suffering AE-IPF [7].

Patients with acute exacerbations have poor outcomes, with rapid decrease in HRQoL [8, 9] and a short-term mortality rate between 50% and 85% [10, 11]. Similarly, FVC decline in IPF has been associated with significant HRQoL deterioration [12, 13] and higher mortality risk [14].

In terms of economic burden, episodes of AE-IPF are also associated with high costs and represent a high economic impact within the IPF-related costs [15, 16]. Likewise, statistically higher economic burden among patients with more impaired lung function has been described [16].

Management of AE-IPF is complex and no international guidelines addressing its prevention and management exist. In current clinical practice many patients receive systemic corticosteroids, although evidence-based international guidelines provide weak recommendations on their use [17, 18]. Results from clinical trials with currently approved treatments for IPF (nintedanib and pirfenidone) suggest that antifibrotics may help with AE-IPF prevention. Specifically, nintedanib has shown robust evidence of AE reduction vs. placebo in two phase 3 studies [19, 20]. Regarding pirfenidone, pivotal studies (CAPACITY and ASCEND) did not specifically assess IPF exacerbations [21, 22]. Additionally, one phase 2 study revealed significant reduction on AE-IPF vs. placebo after 9 months [23], and a phase 3 study did not demonstrate reduction in AE-IPF events after 12 months [24].

The main purpose of the OASIS study was to estimate the socio-economic impact of IPF based on the estimation of total annual healthcare resource use and costs associated with the disease, using the baseline FVC % predicted value in adult patients as a basis for categorization. Additionally, the study evaluated the evolution of HRQoL over the period of a year. Using data collected in the OASIS study we carried out a post-hoc analysis aimed to compare the clinical management, costs and HRQoL of IPF patients who suffered at least one AE-IPF throughout the study with patients who did not suffer AE-IPF.

Materials and methods

Study design

The OASIS study is a prospective, non-interventional, multicenter study based on newly collected data of IPF patients followed-up for one year in secondary care settings. Briefly, patients meeting the selection criteria were enrolled consecutively from 18 December 2017 to 19 July 2018. Key inclusion criteria Inclusion criteria were patients ≥ 40 years old with confirmed IPF diagnosis according to 2011 ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT IPF guidelines [1]. Key exclusion criteria were inability to understand Spanish, concomitant participation in a clinical trial, or inability to follow-up the study procedures. Written informed consent prior to participation was collected from all participants. Sociodemographic and clinical data was collected from medical records and self-administered study questionnaires. Data was collected at 3 visits: at baseline, after 6 and after 12 months. The study was approved by the Ethical Board (EB) of all participant hospitals. The EB of H. Fundación Jiménez Díaz in Madrid, Spain, acted as reference ethics committee. Detailed information about OASIS study can be found elsewhere [6].

Endpoints

In this post-hoc analysis, we aimed to compare the clinical management, costs and HRQoL of IPF patients who suffered at least 1 AE-IPF and those who did not suffer any AE-IPF episode. In this study, AE-IPF was defined as an acute, clinically significant respiratory deterioration characterized by evidence of new widespread alveolar abnormality [5].

Cost analysis

Average annual AE-IPF-related healthcare resource use per patient were collected at 6 and 12 months. Direct costs were calculated by multiplying the number of resources used (i.e., medical visits, ER visits, tests, treatments and hospitalizations) by their corresponding unit costs obtained from Spanish databases and described elsewhere [16]. The total annual costs were calculated as the sum of the direct health costs, direct non-health costs and indirect costs. Details for direct and indirect costs estimation are provided in the supplementary material. The costs were consulted at the time of the analysis, and all costs were expressed and inflated to 2019 euros. At the time of publication, results were updated to 2023 euros using the published cumulative consumer price index [25].

All costs were estimated per patient per year. Also, specific costs for AE-IPF events were estimated. Cost-evaluable population included those patients with at least 6 months of follow-up (with data at the T6 visit). A full description of cost analysis can be found elsewhere [16].

HRQoL measures

Patients’ self-perceived HRQoL was measured with the St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), the EuroQoL 5 dimensions 5 levels questionnaire (EQ-5D-5L), the EQ-5D visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS) and the Barthel Index (BI).

The SGRQ is a 50-item questionnaire covering three domains: respiratory symptoms (frequency and severity), activity (effects of shortness of breath on physical activities and vice versa) and psychological impact and social functioning. The final score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating poorer HRQoL. The Spanish validated version of the questionnaire was used in the present study [26]. SGRQ was chosen due to the extensive validation and comparability across different populations with different respiratory diseases.

The EQ-5D-5L covers five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. The EQ-5D-5L index score ranges from − 0.148 to 0.949 corresponding to “state worse than death” and “optimum quality of life”, respectively. Respondents also rated their overall health on a visual analogue scale (VAS), scored from 0 to 100, with the higher value reflecting a better HRQoL.

The Barthel Index evaluates performance in activities of daily living, and covers 10 domains: ‘feeding’, ‘transfers (bed to chair and back)’, ‘grooming’, ‘toilet use’, ‘bathing’, ‘mobility on level surfaces’, ‘stairs’, ‘dressing’, ‘bowel control’ and ‘bladder control’. The final score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher values reflecting a better personal autonomy and better HRQoL. In the present study the Spanish validated version of the BI was used [27].

Statistical analysis

Mean and standard deviation (SD) were calculated for all continuous variables recorded, and valid n are presented. Categorical variables were presented as number (n) and percentage.

The categorical variables were analyzed using the Chi-square or Fisher test, as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared between groups using Mann–Whitney U test, Kruskal-Wallis test or Wilcoxon signed-rank test, as appropriate.

A statistical significance level of 0.05 was applied in all the statistical tests. Statistical analysis was carried out using SAS® software, version 9.4 [28].

Results

Patient disposition

A total of 204 patients diagnosed with IPF from 28 Spanish sites were included in the study, with a mean follow-up of 12.40 (SD: 1.07) months. Patients were divided in 2 groups according to whether or not they suffered AE-IPF during the study. A total of 22 (10.8%) patients experienced at least one acute exacerbation (1.27 in average), and 182 (89.2%) did not. Thirty (14.7%) patients died during the study period, being mortality significantly higher among patients who had suffered at least 1 AE-IPF (p < 0.001) (Table A.1 in the Appendix). Similarly, study discontinuation was significantly higher among patients with at least one exacerbation during the study than in patients without exacerbations, both at 6 and 12 months (p < 0.0001 for both comparisons) (data not shown).

Baseline characteristics

Baseline sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of included patients are presented in Table 1. Patients who suffered at least 1 AE-IPF were mostly male (90.9%) with a mean age of 70 years. These patients showed a significantly impaired lung function, with higher values of predicted corrected diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide (DLCO-c) (%DLCO-c predicted 37.46% vs. 51.56%; p < 0.001) and they also achieved worse results in the 6MWT: reached a lower distance and demanded higher need for portable oxygen during the test (both, p < 0.05). Moreover, a lower proportion of patients with at least 1 AE-IPF were receiving antifibrotic treatment compared with those patients who did not experience any AE-IPF (p < 0.05) (Table 1).

Use of resources

The final evaluable population for use of resources and cost analysis with at least 6 months of follow-up included 180 subjects: 14 patients with ≥ 1 AE-IPF and 166 without AE-IPF.

Patients with ≥ 1 AE-IPF made significantly more primary care visits along the study compared with patients who did not suffer AE-IPF (57.1% vs. 28.3%; p < 0.05). No differences were observed in the need of specialized care visits between both groups, although nursing home visits were required more significantly among patients with AE-IPF (p < 0.01) (Table 2). All the patients (100%) who suffered ≥ 1 AE-IPF attended emergency visits compared with only 14.5% of patients without exacerbations (p < 0.0001) (Table 2).

Overall, 78.6% of patients suffered at least 1 AE-IPF and required hospital admissions compared with 6.0% of those who did not experience AE-IPF (p < 0.0001). In particular, 21 patients required 41 hospital admissions, with a mean of 8.15 days of hospitalization. In 12.2% of the admissions, patient was admitted at the ICU (Table 2).

No difference was observed with regard to the performance of laboratory tests, pulmonary function tests and other tests between groups.

A total of 180 patients specified 334 pharmacological treatments related to IPF along the study. Patients with AE-IPF reported a significant higher number of pharmacological treatments than patients without exacerbations (p < 0.01). No significant differences on the non-pharmacological treatments between groups were observed (Table 2 and Table A.2 in the Appendix).

Regarding direct non-health use of resources, transport use was required for 42.9% of patients with at least 1 AE-IPF compared with 6.6% of patients without exacerbations (p < 0.001). Up to 50% of patients who suffered at least 1 AE-IPF required help from a caregiver compared with the 19.9% of those without AE-IPF (p < 0.01). No differences with regard to the need of orthoprosthetic material, structural changes or economic aid between groups were observed (Table 2).

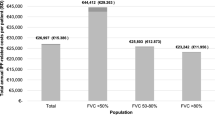

Annual direct and indirect costs

Table 3 shows the total annual costs of IPF per patient categorized by direct health-related, direct non-health related, and indirect costs. Patients who experienced at least one AE-IPF showed a significantly higher annual cost of IPF compared to patients who did not suffer AE-IPF during the study (€36,242 vs. €26,218; p < 0.05).

Direct health IPF-related costs differed between patients with and without exacerbations (p < 0.05), being higher in patients with at least one exacerbation than in patients without exacerbations (mean cost per patient per year €35,347 vs. €25,903) (Table 3).

Patients with exacerbations had significant higher costs in secondary care visits (p = 0.0041), emergency visits both at primary care (p = 0.0018) and hospital (p < 0.0001), days of hospitalization (p = 0.0003), outpatient tests (p = 0.0004), and palliative care (p < 0.0001) (Table 3).

In contrast, total direct non-health IPF-related costs and indirect costs did not differ between both groups. To note, patients with exacerbations had significant higher costs associated with transport in ambulance (p = 0.007) and economic aid (p = 0.0029) (Table 3).

Impact of AE-IPF on HRQoL

The impact of AE-IPF on HRQoL was investigated through the change in overall HRQoL scores at 12 months. Patients who suffered at least 1 AE-IPF experienced a substantial decline of HRQoL compared with patients without AE-IPF (3-fold to 5-fold in all the questionnaires). These differences only reached statistical significance in the EQ-VAS (Table 4).

Of relevance, IPF patients without AE-IPF also suffered statistically significant (p < 0.05) impairment of HRQoL along the study by means of all the measured HRQoL scores except for the BI overall score (Table 4).

Discussion

The outcomes of this project provide data on current clinical and economic burden of AE-IPF in Spain. The main results of the study show higher resource use, higher cost consumption and worse HRQoL in patients who suffered at least one exacerbation during the one year of follow-up.

Exacerbations are unpredictable events that can affect any patient with IPF. Although available data on AE-IPF epidemiology is limited, a meta-analysis from placebo-controlled trials revealed an average of 4.1 AE-IPF per 100 patient-year [29]. In the present work, 10.8% of participants suffered an acute exacerbation in 12 months. This is in line with previous published data, with reported incidence rates between 4.8% and 14.2% [7, 24].

At baseline, patients who later suffered AE-IPF had a significantly more impaired lung function by means of % DLCO-c, and achieved worse results in the 6MWT. Previous publications have also identified DLCO-c, and low 6-minute walk distance as a baseline risk factors for increased risk of exacerbations [7, 30, 31]. On the other hand, a lower FVC is a well-established risk factor for suffering AE-IPF [7, 32], but in the present study no differences in FVC% predicted at baseline between groups were observed. Moreover, although demographic factors such as BMI or never having smoked have been associated with higher risk of suffering AE-IPF [7, 32], no differences on demographics were observed between groups at baseline.

In contrast, baseline management was significantly different between patients: a lower proportion of patients with ≥ 1 AE-IPF received antifibrotics compared with patients without AE-IPF. This data suggests a protective effect of antifibrotics (nintedanib or pirfenidone) on future AE-IPF. Specifically, nintedanib has demonstrated a reduction in centrally adjudicated AE-IPF (confirmed or suspected) vs. placebo (5.7% vs. 1.9%; p = 0.01) in a clinical trial [19]. Furthermore, a combined-evidence publication from data of one phase 2 and two phase 3 clinical trials with nintedanib has demonstrated a significant reduction on the risk of suffering AE-IPF of 47% studies [20]. Pivotal studies for pirfenidone (CAPACITY and ASCEND) did not specifically assess IPF exacerbations, but demonstrated lower risk of hospital admissions and better outcomes [21, 22]. Additionally, pirfenidone has shown significant reduction on AE-IPF vs. placebo after 9 months in a phase 2 study [23], although did not demonstrate reduction in AE-IPF events after 12 months in a phase 3 study [24]. A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the impact of antifibrotics on AE-IPF observed that nintedanib appeared to reduce the risk of AE-IPF, but not pirfenidone [33]. Currently, there are no guidelines on AE-IPF prevention, but in a Delphi study among pulmonologists from 66 countries, antifibrotic drugs were stated as a common preventive strategy for AE-IPF, in particular among physicians in Europe (90%) [34]. Since AE-IPF can any affect any patient, even those with preserved FVC, entailing devastating consequences, preventive strategies are imperative.

When considering management of AE-IPF, International guidelines only provide weak recommendations for systemic corticosteroids use [17], in line with results of the present study, where 12.8% of patients with AE-IPF received systemic corticosteroids, vs. 4.7% of patients without exacerbations. Apart from this, antifibrotics were significantly more prescribed among patients without exacerbations along the study. Indeed, in a Delphi study most participants recommend initiating antifibrotic treatment at the time of AE-IPF in naïve patients and in patients already on antifibrotic therapy, 76% of respondents recommended its continuation [34]. In the present study, lower prescription patterns of antifibrotics were observed, maybe due to physician concerns on risk/benefit profile of antifibrotic treatment, price issues or restrictions due to public policies, among others [2, 35].

Suffering AE-IPF is associated to worse patients’ prognosis, such as higher mortality. Actually, suffering at least one acute exacerbation during one year is associated with a risk of death 10-fold higher than in patients without exacerbations [7, 14], with a median survival of around 3–4 months after the exacerbation [7, 30]. In the present study, significantly more patients who suffered at least 1 AE-IPF died compared with patients without AE-IPF. Moreover, suffering AE-IPF entails a higher decline in FVC%, and patients with a FVC decline > 10% are at higher risk of death than those with FVC decline < 5% [14]. In turn, declines in FVC also prompt to suffer AE-IPF. Thus, it is necessary to make all available therapeutic efforts to avoid AE-IPF and FVC decline to prevent the loop exacerbations/FVC decline to minimize the patient’s burden of the disease. Given the morbidity associated to AE-IPF, investment on effective treatment options is mandatory.

Our study shows that suffering AE-IPF is associated with higher healthcare resource use and subsequently higher economic impact on health systems, especially in terms of direct healthcare resources. Some studies on resource use and costs in IPF patients have been previously published [15, 36, 37], and higher healthcare resource use and costs have been associated to AE-IPF [38,39,40]. Here, emergency visits and hospitalizations were significantly higher in patients with AE-IPF. In this line, Diamantopoulus et al. reported that the odds of hospitalization are > 14 times higher in patients suffering at least 1 AE-IPF [41]. Our previous data also revealed that the cost of an AE-IPF was €10,372 [16]. Similarly, Morell et al. estimated through a Delphi panel that AE-IPF are one of the most important variables contributing to the total annual IPF-costs with a mean cost of 11,718€ per event [15].

The impact of AE-IPF is not only clinical and economical, but also impacts on society and patient’s HRQoL. Experiencing AE-IPF has been associated with greater deterioration in HRQoL [30, 42, 43]. In the present study, the decline in HRQoL determined by SGRQ, EQ-5D-5 L, EQ-VAS and BI scorings in patients with AE-IPF was more notable than in patients without exacerbations, however the progressive decline in QoL due to the nature of the disease was also seen in the population without exacerbations. During 12 months, the drop in terms of HRQoL was around 3 to 5-fold higher in patients with AE-IPF compared with patients without exacerbations, and similar patterns were obtained from phase III INPULSIS trial [42]. In the present study, differences were significant only for the EQ-VAS score, probably due to the small sample size in the group with exacerbations. Therefore, this faster HRQoL impairment observed among patients with exacerbations should be considered when planning their clinical management. Due to the exploratory nature of our research these HRQoL results do not imply direct causality and should be carefully interpreted.

Strengths and limitations

Sample size of patients with at least one exacerbation with > 6 months follow-up was limited and it may have affected statistically significant comparisons in some parameters. On the other hand, multiple comparisons are conducted in our study. Given the exploratory nature of our research, they are primarily intended to generate hypothesis rather than test predefined ones. Future research should be focused on testing and validating specific findings.

For cost analysis calculation, patients who died six months after baseline were not included in the analysis, since no data in terms of resource use could be collected. Moreover, clinical impairment of IPF patients during follow up may have impacted data for specific resource use (e.g. inability to perform respiratory function tests). In addition, estimation of resource use may have been affected by recall bias and/or incomplete medical records. To note, comorbidities that could impact resource utilization might not be fully captured in this study, since only treatments and resources related to IPF were collected. Besides, the particular impact of either nintedanib or pirfenidone on exacerbations cannot be elucidated because these agents were not studied separately. Lastly, the present study was carried out in Spain, and therefore, the results may not be valid for extrapolation to other countries, as the healthcare systems widely differ, especially concerning medicines cost.

Although we acknowledge these limitations and especially the small sample size, we believe that our findings provide valuable preliminary insights in areas with limited availability of literature coming from real-world data. Our study offers an in-depth analysis of the impact of AE-IPF in terms of use of resources, costs and HRQoL of patients suffering from them, and sheds light for a better management of a particularly frail population. Future research with larger sample sizes is necessary to validate these findings and expand on the insights gained from this study.

Future directions

The management of AE-IPF is a major unmet medical need that entails important consequences for patients with IPF. Given that AE-IPF affect patients with preserved FVC and are unforeseeable events, preventing AE-IPF is of paramount importance. Thus, it is crucial to continue working to obtain robust evidence through well-designed studies and to consolidate the results of the present investigation in other settings including higher sample sizes.

Moreover, due to the socioeconomic burden associated to AE-IPF, the results of the present cost study on AE-IPF may help Health Authorities to program planning and designing public policies to deal with IPF socioeconomic burden.

Conclusions

To our knowledge, this is the first study that compares resource use and associated costs of patients with and without AE-IPF, thus contributing to understand the economic burden associated with the disease in Spain.

Our results confirm the higher resource consumption and related costs associated to AE-IPF, together with the decline in HRQoL in patients suffering exacerbations. Thus, preventing or avoiding AE-IPF is important to reduce the use of health resources, as well as to slow the decline in patients’ HRQoL.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AE-IPF:

-

Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- BI:

-

Barthel Index

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- DLCO-c:

-

Carbon monoxide lung diffusion capacity (corrected for haemoglobin)

- EB:

-

Ethical Board

- EQ-5D-5L:

-

EuroQoL 5 dimensions 5 levels questionnaire

- EQ-VAS:

-

EQ-5D visual analogue scale

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- HRQoL:

-

Health related quality of life

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- N:

-

Number

- SD:

-

Standard Deviation

- SGRQ:

-

St. George’s Respiratory Questionnaire

References

Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, Martinez FJ, Behr J, Brown KK, Colby TV, Cordier J-F, Flaherty KR, Lasky JA, Lynch DA, Ryu JH, Swigris JJ, Wells AU, Ancochea J, Bouros D, Carvalho C, Costabel U, Ebina M, Hansell DM, Johkoh T, Kim DS, King TE, Kondoh Y, Myers J, Müller NL, Nicholson AG, Richeldi L, Selman M, Dudden RF, Griss BS, Protzko SL, Schünemann HJ. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:788–824.

Maher TM, Strek ME. Antifibrotic therapy for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: time to treat. Respir Res. 2019;20:205. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-019-1161-4

Xaubet A, Ancochea J, Bollo E, Fernández-Fabrellas E, Franquet T, Molina-Molina M, Montero MA, Serrano-Mollar A. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2013;49:343–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbr.2013.06.003

Ley B, Collard HR, King TEJ. Clinical course and prediction of survival in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:431–40. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201006-0894CI

Collard HR, Ryerson CJ, Corte TJ, Jenkins G, Kondoh Y, Lederer DJ, Lee JS, Maher TM, Wells AU, Antoniou KM, Behr J, Brown KK. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis an international working group report. 2016;194:265–75. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201604-0801CI

Cano-Jiménez E, Romero Ortiz AD, Villar A, Rodríguez-Nieto MJ, Ramon A, Armengol S. Clinical management and acute exacerbations in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Spain: results from the OASIS study. Respir Res. 2022;23:235. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02154-y

Song JW, Hong SB, Lim CM, Koh Y, Kim DS. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:356–63. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00159709

Kreuter M, Swigris J, Pittrow D, Geier S, Klotsche J, Prasse A, Wirtz H, Koschel D, Andreas S, Claussen M, Grohé C, Wilkens H, Hagmeyer L, Skowasch D, Meyer JF, Kirschner J, Gläser S, Kahn N, Welte T, Neurohr C, Schwaiblmair M, Held M, Bahmer T, Oqueka T, Frankenberger M, Behr J. The clinical course of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and its association to quality of life over time: longitudinal data from the INSIGHTS-IPF registry. Respir Res. 2019;20:59. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-019-1020-3

Rajala K, Lehto JT, Sutinen E, Kautiainen H, Myllärniemi M, Saarto T. Marked deterioration in the quality of life of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis during the last two years of life. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0738-x

Spagnolo P, Tzouvelekis A, Bonella F. The management of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Front Med. 2018;5:1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2018.00148

Juarez MM, Chan AL, Norris AG, Morrissey BM, Albertson TE. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis-a review of current and novel pharmacotherapies. J Thorac Disease. 2015;7:499–519. https://doi.org/10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.01.17

Kreuter M, Swigris J, Pittrow D, Geier S, Klotsche J, Prasse A, Wirtz H, Koschel D, Andreas S, Claussen M, Grohé C, Wilkens H, Hagmeyer L, Skowasch D, Meyer JF, Kirschner J, Gläser S, Herth FJF, Welte T, Neurohr C, Schwaiblmair M, Held M, Bahmer T, Frankenberger M, Behr J. Health related quality of life in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in clinical practice: insights-IPF registry. Respir Res. 2017;18:139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0621-y

Glaspole IN, Chapman SA, Cooper WA, Ellis SJ, Goh NS, Hopkins PM, Macansh S, Mahar A, Moodley YP, Paul E, Reynolds PN, Walters EH, Zappala CJ, Corte TJ. Health-related quality of life in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: data from the Australian IPF registry. Respirology. 2017;22:950–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.12989

Paterniti MO, Bi Y, Rekić D, Wang Y, Karimi-Shah BA, Chowdhury BA. Acute exacerbation and decline in forced vital capacity are associated with increased mortality in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Annals Am Thorac Soc. 2017;14:1395–402. https://doi.org/10.1513/AnnalsATS.201606-458OC

Morell F, Esser D, Lim J, Stowasser S, Villacampa A, Nieves D, Brosa M. Treatment patterns, resource use and costs of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Spain - results of a Delphi panel. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16:1–9.

Rodríguez-Nieto MJ, Cano-Jiménez E, Romero Ortiz AD, Villar A, Morros M, Ramon A, Armengol S. Economic burden of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in Spain: a prospective real-world data study (OASIS study). PharmacoEconomics. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40273-023-01278-3

Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, Thomson CC, Inoue Y, Johkoh T, Kreuter M, Lynch DA, Maher TM, Martinez FJ, Molina-Molina M, Myers JL, Nicholson AG, Ryerson CJ, Strek ME, Troy LK, Wijsenbeek M, Mammen MJ, Hossain T, Bissell BD, Herman DD, Hon SM, Kheir F, Khor YH, Macrea M, Antoniou KM, Bouros D, Buendia-Roldan I, Caro F, Crestani B, Ho L, Morisset J, Olson AL, Podolanczuk A, Poletti V, Selman M, Ewing T, Jones S, Knight SL, Ghazipura M. Wilson, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (an update) and progressive pulmonary fibrosis in adults: an official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;205:e18–47. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202202-0399ST

Farrand E, Vittinghoff E, Ley B, Butte AJ, Collard HR. Corticosteroid use is not associated with improved outcomes in acute exacerbation of IPF. Respirol (Carlton Vic). 2020;25:629–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/resp.13753

Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, Cottin V, Flaherty KR, Hansell DM, Inoue Y, Kim DS, Kolb M, Nicholson AG, Noble PW, Selman M, Taniguchi H, Brun M, Le Maulf F, Girard M, Stowasser S, Schlenker-Herceg R, Disse B, Collard HR. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2071–82. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402584

Richeldi L, Cottin V, du Bois RM, Selman M, Kimura T, Bailes Z, Schlenker-Herceg R, Stowasser S, Brown KK. Nintedanib in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: combined evidence from the TOMORROW and INPULSIS® trials. Respir Med. 2016;113:74–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2016.02.001

Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, Costabel U, Glassberg MK, Kardatzke D, King TE, Lancaster L, Sahn SA, Szwarcberg J, Valeyre D. Du bois, pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377:1760–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60405-4

King TEJ, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, Fagan EA, Glaspole I, Glassberg MK, Gorina E, Hopkins PM, Kardatzke D, Lancaster L, Lederer DJ, Nathan SD, Pereira CA, Sahn SA, Sussman R, Swigris JJ, Noble PW. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:2083–92. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1402582

Azuma A, Nukiwa T, Tsuboi E, Suga M, Abe S, Nakata K, Taguchi Y, Nagai S, Itoh H, Ohi M, Sato A, Kudoh S, Raghu G. Double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:1040–7. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200404-571OC

Taniguchi H, Ebina M, Kondoh Y, Ogura T, Azuma A, Suga M, Taguchie Y, Takahashi H, Nakata K, Sato A, Takeuchi M, Raghu G, Kudoh S, Nukiwa T, Betsuyaku T, Sugawara Y, Fujiuchi S, Yamauchi K, Konishi K, Munakata M, Kimura Y, Ishii Y, Sugiyama Y, Kudoh K, Saito T, Yamaguchi T, Mizoo A, Nagai A, Ishizaka A, Yamaguchi K, Yoshimura K, Oritsu M, Fukuchi Y, Takahashi K, Kimura K, Yoshizawa Y, Nagase T, Hisada T, Ohta K, Yoshimori K, Miyazawa Y, Tatsumi K, Sasaki Y, Taniguchi M, Sugita Y, Suzuki E, Saito Y, Nakamura H, Chida K, Kasamatsu N, Hayakawa H, Yasuda K, Suganuma H, Genma H, Tamura R, Shirai T, Shindoh J, Sato S, Taguchi O, Sasaki Y, Ibata H, Yasui M, Nakano Y, Ito M, Kitada S, Kimura H, Inoue Y, Yasuba H, Mochizuki Y, Horikawa S, Suzuki Y, Katakami N, Tanimoto Y, Hitsuda Y, Burioka N, Sato T, Kohno N, Yokoyama A, Nishioka Y, Ueda N, Kuwano K, Watanabe K, Aizawa H, Kohno S, Mukae H, Kohrogi H, Kadota J, Tokimatsu I, Miyazaki E, Sasaki T. M. Kawabata, Pirfenidone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:821–829. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00005209

Instituto Nacional de estadística. Cálculo de variaciones del Índice de Precios de Consumo (sistema IPC base 2021) – Enero 2019 a Enero 2023, (n.d.). https://www.ine.es/varipc/verVariaciones.do;jsessionid=3D690670881EC9EE56C25F8CBD0A524A.varipc03?idmesini=1&anyoini=2019&idmesfin=1&anyofin=2023&ntipo=1&enviar=Calcular (accessed April 10, 2023).

Capparelli I, Fernandez M, Saadia Otero M, Steimberg J, Brassesco M, Campobasso A, Palacios S, Caro F, Alberti ML, Rabinovich RA, Paulin F. Traducción Al español Y validación Del Cuestionario Saint George específico para fibrosis pulmonar idiopática. Arch Bronconeumol. 2018;54:68–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arbres.2017.09.004

Bernaola-Sagardui I. Validation of the Barthel index in the Spanish population. Enfermeria Clin (English Edition). 2018;28:210–1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2017.12.001

SAS Institute Inc., SAS® software, version 9.4. (2016).

Atkins CP, Loke YK, Wilson AM. Outcomes in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a meta-analysis from placebo controlled trials. Respir Med. 2014;108:376–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2013.11.007

Collard HR, Yow E, Richeldi L, Anstrom KJ, Glazer C. Suspected acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis as an outcome measure in clinical trials. Respir Res. 2013;14:73. https://doi.org/10.1186/1465-9921-14-73

Mura M, Porretta MA, Bargagli E, Sergiacomi G, Zompatori M, Sverzellati N, Taglieri A, Mezzasalma F, Rottoli P, Saltini C, Rogliani P. Predicting survival in newly diagnosed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a 3-year prospective study. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:101–9. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00106011

Kondoh Y, Taniguchi H, Katsuta T, Kataoka K, Kimura T, Nishiyama O, Sakamoto K, Johkoh T, Nishimura M, Ono K, Kitaichi M. Risk factors of acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis., sarcoidosis, vasculitis, and diffuse lung diseases. Official J WASOG. 2010;27:103–10.

Petnak T, Lertjitbanjong P, Thongprayoon C, Moua T. Impact of antifibrotic therapy on mortality and acute exacerbation in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest. 2021;160:1751–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHEST.2021.06.049

Kreuter M, Polke M, Walsh SLF, Krisam J, Collard HR, Chaudhuri N, Avdeev S, Behr J, Calligaro G, Corte T, Flaherty K, Funke-Chambour M, Kolb M, Kondoh Y, Maher TM, Molina Molina M, Morais A, Moor CC, Morisset J, Pereira C, Quadrelli S, Selman M, Tzouvelekis A, Valenzuela C, Vancheri C, Vicens-Zygmunt V, Wälscher J, Wuyts W, Wijsenbeek M, Cottin V, Bendstrup E. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: international survey and call for harmonisation. Eur Respir J. 2020;55:1901760. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01760-2019

Maher TM, Swigris JJ, Kreuter M, Wijsenbeek M, Cassidy N, Ireland L, Axmann J, Nathan SD. Identifying barriers to idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis treatment: a survey of patient and physician views., respiration. Int Rev Thorac Dis. 2018;96:514–24.

Farrand E, Iribarren C, Vittinghoff E, Levine-Hall T, Ley B, Minowada G, Collard HR. Impact of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis on longitudinal health-care utilization in a community-based cohort of patients. Chest. 2021;159:219–27.

Fan Y, Bender SD, Conoscenti CS, Davidson-Ray L, Cowper PA, Palmer SM, de Andrade JA. Hospital-based resource use and costs among patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis enrolled in the idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis prospective outcomes (IPF-PRO) registry. Chest. 2020;157:1522–30.

Collard HR, Ward AJ, Lanes S, Cortney Hayflinger D, Rosenberg DM, Hunsche E. Burden of illness in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. J Med Econ. 2012;15:829–35. https://doi.org/10.3111/13696998.2012.680553

Diamantopoulos A, Wright E, Vlahopoulou K, Cornic L, Schoof N, Maher TM. The burden of illness of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a comprehensive evidence review. PharmacoEconomics. 2018;36:779–807.

Yu YF, Macaulay DS, Reichmann WM, Wu EQ, Nathan SD. Association of early suspected acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis with subsequent clinical outcomes and healthcare resource utilization. Respir Med. 2015;109:1582–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rmed.2015.11.001

Diamantopoulos A, Maher TM, Schoof N, Esser D, LeReun C. Influence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis progression on healthcare resource use. PharmacoEconomics - Open. 2019;3:81–91. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41669-018-0085-0

Kreuter M, Kreuter M, Wuyts WA, Wijsenbeek M, Bajwah S, Maher TM, Maher TM, Stowasser S, Male N, Stansen W, Schoof N, Orsatti L, Swigris J. Health-related quality of life and symptoms in patients with IPF treated with nintedanib: analyses of patient-reported outcomes from the INPULSIS® trials. Respir Res. 2020;21:1–12.

Koyama K, Sakamoto S, Isshiki T, Shimizu H, Kurosaki A, Homma S. The activities of daily living after an acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Intern Med (Tokyo Japan). 2017;56:2837–43. https://doi.org/10.2169/internalmedicine.7875-16

Acknowledgements

Alba Gómez, PhD provided writing support and/or formatting assistance. Adelphi Targis, SL, which was contracted and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim España, provided editorial support.

Funding

This work was supported and funded by Boehringer Ingelheim España.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AR and SA were responsible for the original idea and study conceptualization, methodology and supervision, as well as manuscript writing (review and editing). MM contributed in the formal analysis of results, data interpretation and data visualization, and drafting the manuscript. EC, MJR, ADR and AV were involved in the study conceptualization, methodology and investigation, as well as the review and writing of the results (review and editing). All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethical Board (EB) of all participant hospitals. The EB of H. Fundación Jiménez Díaz in Madrid, Spain, acted as reference ethics committee. Detailed information about OASIS study can be found elsewhere [6]. Written informed consent prior to participation was collected from all participants.

Consent for publication

Consent for Publication Not Applicable.

Competing interests

AV has received consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche; fees for talks/lectures from Boehringer Ingelheim, GlaxoSmithKline and Roche; and funding for conferences attendances and courses from Boehringer Ingelheim, Chiesi, Novartis and Roche. MJRN has received funding for research (data monitoring boards), consulting fees and honoraria for presentations/lectures and for being an advisor from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche. ECJ has received funding for research and consulting fees for presentations/lectures and for being an advisor from Boehringer Ingelheim, Galapagos and Roche. ADRO has received funding for research and consulting fees for presentations/lectures and for being an advisor from Boehringer Ingelheim and Roche. MM is a full-time employee of Adelphi Targis. AR and SA are full-time employees of Boehringer Ingelheim España.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it.The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gómez, A.V., Rodríguez-Nieto, M., Cano-Jiménez, E. et al. Clinical and economic burden of acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a prospective observational study in Spain (OASIS study). BMC Pulm Med 24, 370 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-024-03186-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-024-03186-4