Abstract

Background

There is a need to develop and validate a widely applicable nomogram for predicting readmission of respiratory failure patients within 365 days.

Methods

We recruited patients with respiratory failure at the First People’s Hospital of Yancheng and the People’s Hospital of Jiangsu. We used the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator regression to select significant features for multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis. The Random Survival Forest algorithm was employed to construct a model for the variables that obtained a coefficient of 0 following LASSO regression, and subsequently determine the prediction score. Independent risk factors and the score were used to develop a multivariate COX regression for creating the line graph. We used the Harrell concordance index to quantify the predictive accuracy and the receiver operating characteristic curve to evaluate model performance. Additionally, we used decision curve analysiso assess clinical usefulness.

Results

The LASSO regression and multivariate Cox regression were used to screen hemoglobin, diabetes and pneumonia as risk variables combined with Score to develop a column chart model. The C index is 0.927 in the development queue, 0.924 in the internal validation queue, and 0.922 in the external validation queue. At the same time, the predictive model also showed excellent calibration and higher clinical value.

Conclusions

A nomogram predicting readmission of patients with respiratory failure within 365 days based on three independent risk factors and a jointly developed random survival forest algorithm has been developed and validated. This improves the accuracy of predicting patient readmission and provides practical information for individualized treatment decisions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Respiratory failure is a common medical emergency that leads to inadequate blood oxygen levels and/or an increase in blood carbon dioxide levels [1]. Patients with respiratory failure often have multiple cardiovascular and pulmonary complications or may be simultaneously suffering from multiple diseases, and therefore often require prolonged hospitalization, ventilatory support, and intensive care unit admission, resulting in high mortality and high readmission rates [2, 3]. To better address these issues, many experts and clinicians have been dedicated to identifying prognostic models for respiratory failure [4, 5]. We chose readmission as our research indicator because it might be expensive for the healthcare system [6], and it represented an economic and clinical burden for patients [7].

A report on specific disease readmission rates suggested that strategies to reduce readmission rates could be successful, such as with heart failure [8, 9]. However, there are few studies on readmission for respiratory failure. Currently, most research focuses on subtypes of respiratory failure or is limited to early readmission studies [10]. Studies also often include patients with respiratory failure who have other co-occurring conditions [11]. Because respiratory failure is a complex chronic disease caused by multiple risk factors, building a predictive model using Cox regression may not be very effective in predicting individual disease risk [12].

Therefore, the establishment of the readmission model for respiratory failure with complex diseases requires not only accurate risk assessment, but also the interpretation of results based on the importance of covariates to evaluate risk factors, with the ultimate goal of developing better diagnostic and treatment strategies [13]. In fact, important covariates may vary due to environmental factors, and from a clinical perspective, all selected covariates are meaningful [14]. In this case, it is necessary to ensure that the designed model has high prediction accuracy without overfitting, and is universally applicable in clinical diagnosis in the real world [15, 16].

In this study, we attempted to use the random forest model in machine learning to solve this problem, which has good processing capabilities for complex high-dimensional data. The purpose of this study was to establish a widely applicable line chart to predict the occurrence of readmission in patients with respiratory failure at 365 days.

Materials and methods

Study design

The flowchart of this experiment for a multi-center prospective cohort study was depicted in Fig. 1. The study event was respiratory failure. The start time of the study was when the patient was admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of respiratory failure based on blood gas analysis.The endpoint of the study were the occurrence of another respiratory failure event and the time point of hospitalization for the event.

First, the samples collected from the First People’s Hospital of Yancheng were divided into a modeling dataset and an internal validation dataset, and then a line chart was proposed for the study work. Second, the model was evaluated using the internal validation dataset. Third, external validation was performed using data provided by the People’s Hospital of Jiangsu Province. The current project followed the principles of the Helsinki Declaration. This study was approved by the ethics committees of the First People’s Hospital of Yancheng (No.2020-K062) and the People’s Hospital of Jiangsu Province (No. 2021-SR-346). In addition, participants from both hospitals provided written informed consent to support clinical research.

Participants and data collection

We selected 744 patients with respiratory failure who were hospitalized in the First People’s Hospital of Yancheng from October 2020 to September 2021. For external validation, we used a dataset of 223 respiratory failure patients who were hospitalized in Jiangsu Provincial People’s Hospital from October 2021 to December 2021.

The inclusion criteria for research patients were as follows: Arterial oxygen partial pressure (PaO2) was less than 8.0 kPa (60 mmHg) or arterial carbon dioxide partial pressure (PaCO2) was greater than 6.0 kPa (45 mmHg) based on blood gas analysis [17].

Patients with incomplete clinical data, age less than 18 years, death within 24 h, trauma, malignant tumors, malignant hematological diseases, or pregnancy were excluded.

Follow-up index

The primary indicator for respiratory failure patients was the time from discharge to readmission due to respiratory failure. The information was collected from the two centers mentioned above and followed up for 365 days after discharge. To better track patients, we conducted telephone interviews and used hospital systems to verify the patient’s condition further.

Model specification

Firstly, the variables with non-zero coefficients were screened using LASSO regression, followed by multivariate COX regression to identify significant variables. Secondly, the variables excluded by setting their LASSO regression coefficient to 0 and performing multiariable COX regression together were used to construct a new model using the RSF method for prediction. Finally, the meaningful variables identified through COX regression were combined with scores to establish a new multiariable COX regression model.

Statistical analysis

To ensure comparability between the two groups of patients, 744 respiratory failure patients were randomly divided into two groups, with 70% and 30% of patients in each group, respectively. One group (n = 520) was used to develop the Nomogram, while the other group (n = 224) was used to verify the predictive ability of the constructed model.

To test the balance between two groups, categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and their differences were compared using the Chi-square test. For continuous variables, if they followed a normal distribution, they were expressed as mean ± SD, and their differences were compared using the t-test. If they did not follow a normal distribution, they were expressed as median and quartiles, and their differences were compared using the Mann-Whitney test.

The LASSO regression method was utilized to select significant features from the modeling set for multivariate Cox proportional hazard analysis, screening independent risk factors. The Random Survival Forest (RSF) algorithm was employed to construct a model for the variables exhibiting a coefficient of 0 following LASSO regression, and subsequently compute the prediction Score. The predictive accuracy of the nomogram was quantitatively measured using the Harrell consistency index (C index), which calculated time-related receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and areas under the curve to evaluate the model’s performance. The accuracy of the nomogram prediction was evaluated using the calibration curve. Additionally, decision curve analysis (DCA) was used to assess the clinical utility of the nomogram.

Individual risk scores were obtained based on the established nomogram. Risk stratification was determined using the ROC curve to identify the optimal threshold for risk score. The critical value divided patients into high-risk and low-risk groups and provided the best difference for survival analysis between the risk groups. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using R (version 4.1.3).

Result

Baseline characteristics

In this study, we prospectively evaluated a total of 744 patients with respiratory failure who met the inclusion criteria. The evaluation data were summarized and randomly divided into two groups at a ratio of 7:3. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients in the modeling (n = 520) and validation (n = 224) cohorts. In the entire cohort, there were 487 males (65.46%) and 257 females (34.54%), with a median age of 74 years. Type 2 respiratory failure patients accounted for 68.15% of the cohort, while type 1 respiratory failure patients accounted for 31.85%. There were 448 (60.22%) smokers. The top three chronic diseases in terms of prevalence were COPD, with 536 (72.04%) patients, hypertension with 289 (38.84%) patients, and pneumonia with 169 (22.72%) patients. Additionally, 186 patients were readmitted, resulting in a readmission rate of 25%. The clinical characteristics between the two groups were well balanced and comparable. The external test set, which met the inclusion criteria, was obtained from the People’s Hospital of Jiangsu Province.

Feature selection and nomogram construction

We applied the LASSO regression algorithm to each feature for feature selection in the modeling queue. The biased binomial’s partial likelihood deviance reached its minimum, and the most suitable adjustment parameter λ for LASSO regression was 0.028. Figure 2A displayed the coefficient path generated by the logarithmic λ series values. The LASSO analysis retained 11 variables with non-zero coefficients (Fig. 2B): Glutamyltransferase, triglyceride, total cholesterol, myoglobin, lactic acid, carboxyhemoglobin, respiratory failure type, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, asthma, and pneumonia. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis was performed using eleven variables. Ultimately, three independent risk factors were retained: Myoglobin, Diabetes, and Pneumonia (Table 2). The RSF algorithm was utilized to establish a model for the variables with a coefficient of 0 following LASSO regression and compute the prediction score. Then, the three independent risk factors and prognostic scores were integrated into a multivariate Cox regression model to construct a nomogram based on nomogram, showing the probability of recurrence (Fig. 3). To make the prediction model easy to use, we also developed a web-based format(https://respiratory.shinyapps.io/DynNomapp/).

Evaluation and validation of nomogram

A model used to estimate the probability of readmission at 3, 6, and 10 months demonstrated good predictive ability. The C-index was 0.927 (95% CI: 0.910–0.944) in the development cohort, 0.924 (95% CI: 0.901–0.948) in the internal validation cohort, and 0.922 (95% CI: 0.898–0.946) in the external validation cohort.

ROC curve analysis of the line graph in the modeling queue showed excellent classification accuracy, with an AUC of 0.960 (95%CI: 0.942–0.978) at 3 months, 0.970 (95%CI: 0.957–0.983) at 6 months, and 0.963 (95%CI: 0.946–0.981) at 10 months(Fig. 4A). The ROC analysis of the internal validation set confirmed the classification performance, with an AUC of 0.949 (95% CI: 0.920–0.977) at 3 months, 0.961 (95% CI: 0.939–0.984) at 6 months, and 0.966 (95% CI: 0.946–0.986) at 10 months(Fig. 4B). In addition, the ROC analysis of the external test set also verified the classification performance, with an AUC of 0.952 (95% CI: 0.926–0.979) at 3 months, an AUC of 0.960 (95%CI: 0.937–0.983) at 6 months, and an AUC of 0.971 (95%CI: 0.945–0.997) at 10 months(Fig. 4C).The calibration curves for the modeling team, internal validation queue, and external validation queue demonstrate strong consistency between the predicted probability of readmission and the actual occurrence probability at 3, 6, and 10 months(Fig. 5).

Detection of receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. (A) the ROC curve of Modeling set. (B) the ROC curve of internal validation set. (C) the ROC curve of external validation set. The red, yellow, and blue AUC curves show the discrimination of the model at 3, 6, and 10 months. The corresponding 95% confidence interval estimates are highlighted in black text

Clinical application of nomogram

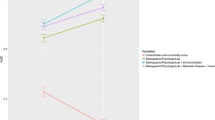

As shown in Fig. 6, the DCA algorithm demonstrated promising clinical value in predicting the probability of readmission at 3, 6, and 10 months. This was evident in the modeling queue, internal validation queue, and external validation queue, where the algorithm outperformed the COX regression model established using three independent risk factors. Specifically, the DCA algorithm utilized a calibration curve to achieve superior performance. The time-dependent AUC revealed consistently higher AUC values for the training set, internal validation set, and external validation set at different time points, indicating a robust and stable discriminative ability of the prediction model across various time intervals (Fig. 7). We used nomogram to calculate the risk value for each patient and then utilized the ROC curve to determine the optimal threshold. Based on this, patients were classified into high-risk (total score ≥ 38.33) and low-risk (total score < 38.33) groups for predicting readmission. The K-M curve illustrated that high-risk patients had a significantly higher readmission rate than low-risk patients across the training, internal validation, and external validation cohorts (Fig. 8).

Individual risk scores obtained from the established nomogram. In the modeling set (A), internal validation set (B) and external validation set (C), individual risk scores were obtained according to the established nomogram, and patients were divided into high-risk group and low-risk group according to the critical value to show the best difference in readmission analysis between risk groups

Discussion

Our study includes demographic data and clinical information such as body mass index, gender, age, various rating scales, smoking history, and laboratory data (e.g., complete blood count, blood biochemistry, blood gas, etc.). We also consider common and important comorbidities like diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and pneumonia. All the features mentioned above are used to predict outcome models.

Improving the predictive form of the RSF model can lead to more accurate individual patient prognoses when establishing a model [18]. The Random Survival Forest algorithm was employed to construct a model for the variables that obtained a coefficient of 0 following LASSO regression, and subsequently determine the prediction score. Additionally, we employed independent risk factors and the score to establish a multivariate COX regression, which was something that traditional scoring systems were unable to achieve.

In our study, we used the Cox model as a baseline predictive model due to its simplicity, allowing for reproducibility and universality [19]. Afterwards, we conducted a random forest survival analysis, in which all predictive factors were included in a single model, using variable importance measures to assess the contribution of each variable to predicting survival [20]. Through the predictive model of readmission risk at 3, 6, and 10 months for patients with respiratory failure, we found that the joint predictive model showed better calibration and discrimination than the single Cox regression model. This model can provide a basis for clinical decision-making. The predictive performance of the model was further validated by employing Time-dependent AUC curves. Our analysis provided insights into predictors of readmission for respiratory failure. We found that patients with acute respiratory failure often returned to the hospital, with pneumonia, diabetes, and myoglobin being identified as the most significant risk factors.

It has been confirmed that pneumonia is the most common cause of readmission for respiratory failure within a year, especially in subgroup analysis of patients undergoing invasive Home mechanical ventilation (HMV) [21]. According to the American Association of Respiratory Care practice guidelines, readmission is usually caused by the worsening of underlying diseases, respiratory tract infections, airway-related side effects, and ventilation failure [22]. In a previous study involving children, 40–70% of discharged patients experienced unplanned readmissions within a short period of approximately 1–3 months after starting HMV, mainly due to pneumonia and respiratory issues [23]. Pneumonia is the main cause of readmission for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease during a one-year period [24]. It can be seen that these reasons for readmission are preventable.

Additionally, patients with acute respiratory failure frequently have elevated blood sugar levels [25]. Diabetes is the most significant risk factor for respiratory failure [26]. Currently, there is no research on the relationship between diabetes and readmission of respiratory failure patients [27, 28]. However, diabetes is a risk factor for readmission of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [29]. This is mainly because patients with respiratory failure and diabetes are more prone to pulmonary infections, airway mucosal congestion, ciliary dysfunction, and airflow restriction, which can worsen respiratory failure and complicate treatment, necessitating timely intervention with ventilation measures [30].

Similarly, the association between myoglobin and readmission in patients with respiratory failure has not been studied. Myoglobin is an iron- and oxygen-binding protein that is involved in the regulation of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV [31]. Myoglobin plays an important role in oxygen storage in skeletal and cardiac muscles, especially in situations of hypoxemia [32]. Long-term hypoxia can cause non-specific damage to multiple organs. This can lead to increased myoglobin expression, which is related to the degree of hypoxia [33]. Elevated levels of myoglobin in critically ill patients with severe infections, burns, shock, and multiple traumas can predict survival rates and patient prognosis [34]. Studies have shown that myoglobin is a predictive indicator of mortality and risk of deterioration in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients with respiratory failure [35]. Moreover, it has been discovered that elevated levels of myoglobin may be due to other comorbidities, such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, and so on [36]. Myoglobin can rapidly be released into the bloodstream as a response to inflammatory stimuli [37]. It is negatively correlated with the percentage of predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients [38]. Our results confirm that serum myoglobin levels may be useful in understanding the progression of critical illness, particularly in predicting readmission due to respiratory failure.

Our research has several advantages. Firstly, we provide a simple and feasible tool for identifying patients who are at risk of readmission. By doing so, interventions can be targeted towards reducing readmissions. Secondly, patients with respiratory failure are at high risk for readmission and should be studied as a group to benefit from personalized plans that reduce readmissions.

There are some limitations to this study. First, there may be potential selection bias, such as sample selection bias and patient inclusion bias. Second, larger-scale studies are needed to confirm the predictive ability of the respiratory failure prediction model.

In summary, this study employed a random survival forest algorithm to merge three independent risk factors for respiratory failure. The resulting model provided a simple and user-friendly tool for predicting the probability of readmission within 365 days for patients with respiratory failure. Internal and external validation further demonstrated the broad applicability and reliability of this model in the classification and management of respiratory failure patients, thereby assisting in timely clinical decision-making.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Lamba TS, Sharara RS, Singh AC, et al. Pathophysiology and classification of respiratory failure [J]. Crit Care Nurs Q. 2016;39(2):85–93.

Fuller GW, Goodacre S, Keating S, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of pre-hospital assessment of acute respiratory failure [J]. Br Paramed J. 2020;5(3):15–22.

Dziadzko MA, Novotny PJ, Sloan J, et al. Multicenter derivation and validation of an early warning score for acute respiratory failure or death in the hospital [J]. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):286.

Cavalot G, Dounaevskaia V, Vieira F, et al. One-year readmission following undifferentiated Acute Hypercapnic Respiratory failure [J]. COPD. 2021;18(6):602–11.

Chu CM, Chan VL, Lin AW, et al. Readmission rates and life threatening events in COPD survivors treated with non-invasive ventilation for acute hypercapnic respiratory failure [J]. Thorax. 2004;59(12):1020–5.

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA. Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program [J]. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(14):1418–28.

Kash BA, Baek J, Davis E, et al. Review of successful hospital readmission reduction strategies and the role of health information exchange [J]. Int J Med Inform. 2017;104:97–104.

Gonseth J, Guallar-Castillon P, Banegas JR, et al. The effectiveness of disease management programmes in reducing hospital re-admission in older patients with heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published reports [J]. Eur Heart J. 2004;25(18):1570–95.

Hauptman PJ, Rich MW, Heidenreich PA, et al. The heart failure clinic: a consensus statement of the Heart Failure Society of America [J]. J Card Fail. 2008;14(10):801–15.

Chen R, Xing L, You C, et al. Prediction of prognosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients with respiratory failure: a comparison of three nutritional assessment methods [J]. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;57:70–5.

Kovalsky D, Roberts MB, Freeze B, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms after respiratory and cardiovascular emergencies predict risk of hospital readmission: a prospective cohort study [J]. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29(5):598–605.

Qian X, Keerman M, Zhang X, et al. Study on the prediction model of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the rural Xinjiang population based on survival analysis [J]. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):1041.

Pittman J, Huang E, Dressman H, et al. Integrated modeling of clinical and gene expression information for personalized prediction of disease outcomes [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(22):8431–6.

Bussy S, Veil R, Looten V, et al. Comparison of methods for early-readmission prediction in a high-dimensional heterogeneous covariates and time-to-event outcome framework [J]. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2019;19(1):50.

Taylor JM. Random Survival forests [J]. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6(12):1974–5.

Ambale-Venkatesh B, Yang X, Wu CO, et al. Cardiovascular Event Prediction by Machine Learning: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis [J]. Circ Res. 2017;121(9):1092–101.

Roussos C, Koutsoukou A. Respiratory failure [J]. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;47:3s–14s.

LIN J, YIN M, LIU L et al. The Development of a Prediction Model Based on Random Survival Forest for the Postoperative Prognosis of Pancreatic Cancer: A SEER-Based Study [J]. Cancers (Basel), 2022, 14(19).

Ji GW, Zhu FP, Xu Q, et al. Machine-learning analysis of contrast-enhanced CT radiomics predicts recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection: a multi-institutional study [J]. EBioMedicine. 2019;50:156–65.

Puterman E, Weiss J, Hives BA, et al. Predicting mortality from 57 economic, behavioral, social, and psychological factors [J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(28):16273–82.

Kim EY, Suh HJ, Seo GJ, et al. Predictors of early hospital readmission in patients receiving home mechanical ventilation [J]. Heart Lung. 2023;57:222–8.

Care Focus AARCRH. AARC clinical practice guideline. Long-term invasive mechanical ventilation in the home–2007 revision & update [J]. Respir Care. 2007;52(8):1056–62.

Kun SS, Edwards JD, Ward SL, et al. Hospital readmissions for newly discharged pediatric home mechanical ventilation patients [J]. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2012;47(4):409–14.

Hakim MA, Garden FL, Jennings MD, et al. Performance of the LACE index to predict 30-day hospital readmissions in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [J]. Clin Epidemiol. 2018;10:51–9.

Edriss H, Molehin AJ, Gavidia R, et al. Association between acute respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation and the production of advanced glycation end products [J]. J Investig Med. 2020;68(7):1235–40.

Edriss H, Selvan K, Sigler M, et al. Glucose levels in patients with Acute Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation [J]. J Intensive Care Med. 2017;32(10):578–84.

Roberts MH, Clerisme-Beaty E, Kozma CM, et al. A retrospective analysis to identify predictors of COPD-related rehospitalization [J]. BMC Pulm Med. 2016;16(1):68.

Barba R, De Casasola GG, Marco J, et al. Anemia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a readmission prognosis factor [J]. Curr Med Res Opin. 2012;28(4):617–22.

Lau CS, Siracuse BL, Chamberlain RS. Readmission after COPD Exacerbation Scale: determining 30-day readmission risk for COPD patients [J]. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2017;12:1891–902.

Sun JA, Wang X, Liu Y et al. An Analysis of the Effect of Noninvasive Positive Pressure Ventilation on Patients with Respiratory Failure Complicated by Diabetes Mellitus [J]. Dis Markers, 2022, 2022: 3597200.

Yamada T, Takakura H, Jue T, et al. Myoglobin and the regulation of mitochondrial respiratory chain complex IV [J]. J Physiol. 2016;594(2):483–95.

Collman JP, Boulatov R, Sunderland CJ, et al. Functional analogues of cytochrome c oxidase, myoglobin, and hemoglobin [J]. Chem Rev. 2004;104(2):561–88.

Olson JS. Kinetic mechanisms for O(2) binding to myoglobins and hemoglobins [J]. Mol Aspects Med. 2022;84:101024.

Yao L, Liu Z, Zhu J, et al. Higher serum level of myoglobin could predict more severity and poor outcome for patients with sepsis [J]. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(6):948–52.

Zhu F, Li W, Lin Q, et al. Myoglobin and troponin as prognostic factors in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia [J]. Med Clin (Engl Ed). 2021;157(4):164–71.

Ma C, Tu D, Gu J, et al. The predictive value of myoglobin for COVID-19-Related adverse outcomes: a systematic review and Meta-analysis [J]. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:757799.

Hendgen-Cotta UB, Kelm M, Rassaf T. Myoglobin functions in the heart [J]. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;73:252–9.

Loza MJ, Watt R, BaribauD F, et al. Systemic inflammatory profile and response to anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [J]. Respir Res. 2012;13(1):12.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhongxiang Liu and Bingqing Zuo designed the study. Zhixiao Sun, Hang Hu and Yuan Yin collected data on clinical patients. Zhongxiang Liu, Zhixiao Sun and Bingqing Zuo builded and validated disease modeling. Zhongxiang Liu and Zhixiao Sun wrote the main manuscript text. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethics committees of the First People’s Hospital of Yancheng (No.2020-K062) and the People’s Hospital of Jiangsu Province (No. 2021-SR-346). Participants from both hospitals provided written informed consent to support clinical research.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Sun, Z., Hu, H. et al. Development and validation of a prospective study to predict the risk of readmission within 365 days of respiratory failure: based on a random survival forest algorithm combined with COX regression modeling. BMC Pulm Med 24, 82 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-024-02862-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-024-02862-9