Abstract

Background

Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces, especially solitary multicystic lesion lung cancer, is a rare disease (a rare imaging performance of non-small cell lung cancer). It is difficult to diagnose owing to the lack of a clear definition; therefore, diagnosis of these neoplastic lesions remains challenging.

Case presentation

We outlined two cases of elderly Chinese men who were admitted to the hospital with a solitary multicystic lesion of the lung and subsequent surgical resection, confirming a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma.

Conclusions

For solitary pulmonary cystic airspaces (especially solitary multicystic lung lesions), it is important to properly recognise their imaging features. Due to the possibility of malignancies, timely surgery is an effective treatment strategy for early diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces (LCCA) is an uncommon manifestation, representing only 1–7% of all lung cancers [1]. Solitary multicystic lesion lung cancer is classified as an adenocarcinoma with the lowest incidence of LCCA [2, 3]. In contrast to the common imaging manifestations of masses or nodules in lung cancer, LCCA is mainly characterised by a cystic area (single or multicystic), with associated consolidation and/or ground-glass opacity [4].

After Womack and Graham first suggested that pulmonary cystic lesions are possibly associated with bronchogenic carcinoma in 1941, Anderson and Pierce reported on carcinoma of the bronchus presenting as thin-walled cysts for the first time in 1954 [2]. Since then, LCCA has been described as a rare disorder owing to the lack of a clear definition for this condition [5]. Coupled with the relatively small number of clinical cases, there is a risk of missed diagnosis or misdiagnosis in the early stage, resulting in a delayed treatment period [6]. Therefore, familiarisation with LCCA and diagnosis and treatment of this special type of lung cancer has become an important goal of our future research.

In this case report, we present two male patients admitted to the hospital with a solitary multicystic lung lesion who had undergone surgical resection, confirming a diagnosis of adenocarcinoma. A review of the conditions focusing on their diagnosis and treatment is also included.

Case presentation

Case 1

A 66-year-old man, who had smoked 20 cigarettes per day for 40 years, presented to the pulmonary department with sudden onset haemoptysis for 1 week. He had other concurrent symptoms, including a chronic wet cough for 20 years, with no associated dyspnoea, chest pain, or weight loss. The patient had no history of any other disease. On initial physical examination, he had a blood pressure of 154/105 mmHg, with a pulse rate of 77 beats per minute (bpm). He had normal heart sounds and clear lungs with no dry or wet rales on auscultation.

Routine laboratory investigations were normal, including complete blood count, serum urea, and electrolyte levels. Tumour markers (carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA], squamous cell carcinoma antigen [SCC-Ag], and neuron-specific enolase [NSE]) were all within normal limits. Chest computed tomography (CT) demonstrated a solitary multicystic lesion with a thin-wall measuring 24 mm × 12 mm in the right upper lobe (Fig. 1), with non-solid nodules along the cyst wall.

A pulmonary function test revealed a forced expiratory volume in 1 s as the percentage of the predicted value (FEV1%pred) of 61% and a ratio of FEV1/forced vital capacity (FVC) reduced to 58.6% (< 70%), suggesting an obstructive ventilatory disturbance due to smoking; this indicates that the patient has chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Two days later, flexible bronchoscopy revealed only blood clots, and bronchoalveolar lavage in the right upper lobe bronchus found neither malignant cells nor acid-fast bacilli (AFB). Noting that the patient already had haemoptysis and that other diseases commonly causing haemoptysis (i.e., bronchiectasis) were not initially considered, a percutaneous CT-guided biopsy of the solitary multicystic lesion was performed two days later. Since the cystic airspace was completely thin-walled, two small pieces of lung tissue were penetrated. Following tissue biopsy fixation, processing, sectioning and routine histochemical staining, histological examination showed alveolar epithelial hyperplasia (AEH) with an adherent growth pattern without excluding adenocarcinoma in situ, microinvasive adenocarcinoma, or invasive adenocarcinoma due to the lack of tissue.

Due to the small amount of tissue acquired with biopsy under transthoracic puncture, the pathological result did not present an exact diagnosis of LCCA. However, the presence of atypical AEH cells raised speculation regarding early LCCA. Surgery is one of the most reliable therapies for pulmonary adenocarcinomas. We subsequently performed a right upper lobectomy with lymph node dissection using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS). Grossly, the sliced resected specimen revealed a tan-whitish cystic tumour, 2.3 cm in length, scattered with small nodules. However, lung cancer was not identified in the frozen section, supporting the diagnosis of a benign mass.

Three days later, a histopathology report documented lepidic-predominant adenocarcinoma with 40% invasive acinar adenocarcinoma. (Fig. 1). The lesion was completely excised. Based on the above findings, the patient was diagnosed with stage IIB pulmonary adenocarcinoma according to the 8th edition of the tumour node metastasis (TNM) staging system for lung cancer. After the operation, the patient was treated with platinum-based adjuvant chemotherapy for four cycles. The postoperative course was uneventful, and there was no recurrence 24 months post-surgery.

Case 2

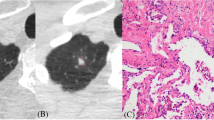

Patient 2 was a 56-year-old man who had no smoking history and presented to the pulmonary department with no symptoms. Radiological examination revealed a cyst measuring 10 mm × 8 mm in the left upper lung (Fig. 2). The doctor in our department included LCCA as a differential diagnosis due to the previous case and suggested that the patient undergo further diagnostic tests for clarification. Laboratory findings showed elevated serum levels of NSE (18.07 ng/mL, normal 0–16.30 ng/mL), CEA, and cytokeratin fragment 21-1 (CYFRA21-1), whereas other routine laboratory investigations and pulmonary function test results were normal. After the failure of percutaneous CT-guided biopsy of the solitary multicystic lesion, a left upper lobectomy was performed using video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS).

The pathological results showed that invasive adenocarcinoma was found in the cyst region, and almost all components were acinar (Fig. 2). The lesion was completely excised. After the operation, he did not receive any additional chemotherapy and recovered well.

Discussion and conclusions

Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces (LCCA) has been reported since the 1940s; however, it is still currently considered as a relatively rare tumour (a rare imaging performance of NSCLC). In 2017, Fintelmann et al. [7] showed that LCCA accounts for approximately 1% of NSCLC, with the majority classified as adenocarcinoma and found in former and current smokers with pulmonary emphysema.

As LCCA has an overall low prevalence, it is easy for radiologists and respiratory doctors to miss it [8]. Patients with LCCA tend to have a worse prognosis than those with non-cystic airspaces lung cancer. Early diagnosis may be challenging, and the condition may already be advanced at the time of detection.

Therefore, CT image features and possible carcinogenic mechanisms may help us understand and diagnose cystic airspace cancers [7, 9]. Currently, only a few retrospective studies have analysed radiological or pathological diagnostic criteria or the management of this condition [10, 11]. In the current radiological system categorising all LCCA, four morphologic types of pericystic cancers have been described by Mascalchi et al. [3, 12]: Type I represents a nodule outside the cystic airspace and abutting the wall. Type II is that of a nodule projecting into the cystic airspace from the wall. Type III is cyst wall thickening, which may not necessarily be circumferential and without an area of focal nodularity. Type IV is a multicystic lesion with focal soft-tissue elements. The two cases, which have been described, belong to this special type of classification system. In addition, Jung et al. [13] showed us the imaging morphological changes in LCCA at different developmental stages, reflecting the natural clinical course and clinicopathological features of LCCA. The true pathogenesis of the cystic airspace is not yet fully understood; however, the different causes have been described [14,15,16,17,18], including (1) central necrosis of tumour; (2) a check-valve mechanism of small airway dilatation with scar tissue; (3) direct destruction of alveolar walls by lung cancer cells; (4) lepidic growth of adenocarcinoma on emphysematous lung parenchyma; (5) cancer arising from clusters of mucinous cells in the walls of this type of congenital pulmonary airway malformation; (6) growth of adenocarcinoma along the wall of a preexisting bulla; (7) and autophagy of cancer cells.

Cystic airspaces are not always present. Most LCCA lesions have new or increased nodular components or thickening of the wall over time. Sheard et al. [5] reported some cases which showed thickening around the periphery of a bulla, and the bulla had progressed to an eccentric or solid nodule. CT scans showed a continued growth of the bulla that was initially misinterpreted as an inflammation, which later became multicystic before evolving into a solid lesion. Mascalchi [12] reported on the comparison of initial and subsequent CTs and revealed that as the solid component increased, the diameter of the cystic airspace decreased or became completely solid in most of his patients. This duration can explain why we misunderstood the initial CT images of the LCCA. In these patients, the risk of death was increased since we were not familiar with the early stages of the tumour, which is the cystic airspace. If we fully understand the CT image development process of the disease, early diagnosis and initiation of treatment in LCCA may alter disease outcomes [19]. The mortality rates of early stage lung cancer resection remain low. Fintelmann et al. [7] reported that the median time between the first observation of a cystic airspace and lung cancer diagnosis was 25.5 months. Thus, cystic airspaces with wall thickening and/or associated nodules of any attenuation warrant regular surveillance. Simultaneously, thoracoscopic surgery is indispensable as a minimally invasive approach for patients with highly suspicious lung cancer.

After a CT scan shows the initial examination of cystic airspaces, appropriate further radiological and invasive operations may be required for the diagnosis of LCCA. Normal clinical inspection such as transbronchial biopsy, percutaneous lung biopsy, and positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) are helpful but insufficient for special types such as type IV multicystic lesion, as mentioned in the two cases [20].

Mendoza et al. found that more than 300 cases of LCCA have been described [11] in the form of case reports or small case series; most cases have been diagnosed by surgery in the literature. Farooqi et al. [10] identified 26 cases of abutting lung cysts, and 25 cases were diagnosed by resection. Guo et al. [21] identified 15 cases of “lung cancer presenting as cysts”; all were from surgical resection cases. However, a different conclusion has been drawn by Mascalchi et al. [3, 12], who reported 24 cases of lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces, and the diagnosis of malignancy was based on cytologic examination on CT-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) (n = 18) or histologic diagnosis of the surgical specimen or core biopsy (n = 6) [5]. In clinical practice, FNAB has been shown to be a safe and effective method for establishing a diagnosis of pulmonary solid and subsolid lesions [22]. However, for LCCA, especially type IV, it often ends in failure due to the small size of the lesion and the difficulty of sampling, as shown in case 2. Therefore, we should recognise the limitations of preoperative biopsy in the diagnosis of these patients.

In contrast, PET-CT has a number of drawbacks in LCCA. Small and cystic air space lesions, multicystic type IV in particular, may reduce the overall density of metabolically active cells; hence, the uptake of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) in a small pericystic lesion can be difficult to measure, and a negative PET result does not reliably exclude malignancy [9, 12, 23, 24].

We report two cases of type IV LCCA that showed multicystic lesions. With increased physician suspicion and improved CT scan and puncture biopsy techniques, the diagnosis rate of LCCA has increased, but it is still often overlooked and misdiagnosed. The majority of cancers associated with cystic airspaces are of the adenocarcinoma type. Awareness of these CT features is important, and the limitations of preoperative biopsy and PET-CT should be recognised. Timely surgery is essential for early diagnosis.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- LCCA:

-

Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces

- NSCLC:

-

Non-small cell lung cancer

- bpm:

-

Beats per minute

- CEA:

-

Carcinoembryonic antigen

- SCC-Ag:

-

Squamous cell carcinoma antigen

- NSE:

-

Neuron-specific enolase

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FEV1:

-

A forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- AFB:

-

Acid-fast bacilli

- AEH:

-

Alveolar epithelial hyperplasia

- VATS:

-

Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery

- TNM:

-

Tumour node metastasis

- CYFRA21-1:

-

Cytokeratin fragment 21-1

- PET-CT:

-

Positron emission tomography-computed tomography

- FNAB:

-

Fine-needle aspiration biopsy

- FDG:

-

Fluorodeoxyglucose

References

Haider E, et al. Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces: characteristic morphological features on CT in a series of 11 cases. Clin Imaging. 2019;56:102–7.

Anderson HJ, Pierce JW. Carcinoma of the bronchus presenting as thin-walled cysts. Thorax. 1954;9(2):100–5.

Mascalchi M. Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces in the screening perspective. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(Suppl 3):960–1.

Watanabe Y, et al. Surgically resected solitary cavitary lung adenocarcinoma: association between clinical, pathologic, and radiologic findings and prognosis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99(3):968–74.

Sheard S, et al. Lung cancers associated with cystic airspaces: underrecognized features of early diease. Radiographics. 2018;38(3):704–17.

Wang X, et al. Solitary thin-walled cystic lung cancer with extensive extrapulmonary metastasis: a case report and review of the literature. Med (Baltim). 2018;97(43):e12950.

Fintelmann FJ, et al. Lung cancers associated with cystic airspaces: natural history, pathologic correlation, and mutational analysis. J Thorac Imaging. 2017;32(3):176–88.

Opoka LM, et al. CT imaging features of thin-walled cavitary squamous cell lung cancer. Adv Respir Med. 2019;87(2):114–7.

Shen Y, et al. Lung cancers associated with cystic airspaces: CT features and pathologic correlation. Lung Cancer. 2019;135:110–5.

Farooqi AO, et al. Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199(4):781–6.

Mendoza DP, et al. Clinicopathologic and longitudinal imaging features of lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2021;216(2):318–29.

Mascalchi M, et al. Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2015;39(1):102–8.

Jung W, Cho S, Yum S, et al. Stepwise disease progression model of subsolid lung adenocarcinoma with cystic airspaces. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27(11):4394–403.

Hurley P, Corbishley C, Pepper J. Bronchioloalveolar carcinoma arising in longstanding lung cysts. Thorax. 1985;40(12):960.

Guo J, et al. Thin-walled cystic lung cancer: an analysis of 24 cases and review of literatures. Zhongguo Fei Ai Za Zhi. 2014;17(7):553–6.

Zhang J, et al. The mechanism of formation of thin-walled cystic lung cancer. Med (Baltim). 2019;98(14):e15031.

Meng SS, et al. Lung cancer from a focal bulla into thin-walled adenocarcinoma with ground glass opacity—an observation for more than 10 years: a case report. World J Clin Cases. 2020;8(11):2312–7.

Snoeckx A, Reyntiens P, Pauwels, et al. Molecular profiling in lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces. Acta Clin Belg. 2021;76(2):158–61.

Penha D, et al. Lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces: a new radiological presentation of lung cancer. J Bras Pneumol. 2020;46(6):e20200156.

Kandathil A, et al. Role of FDG PET/CT in the eighth edition of TNM staging of non-small cell lung cancer. Radiographics. 2018;38(7):2134–49.

Guo J, et al. Lung cancer presenting as thin-walled cysts: an analysis of 15 cases and review of literature. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2016;12(1):e105-112.

Kiranantawat N, et al. Determining malignancy in CT guided fine needle aspirate biopsy of subsolid lung nodules: is core biopsy necessary? Eur J Radiol Open. 2019;6:175–81.

Ambrosini V, et al. PET/CT imaging in different types of lung cancer: an overview. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81(5):988–1001.

Snoeckx A, et al. Diagnostic and clinical features of lung cancer associated with cystic airspaces. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11(3):987–1004.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

Project of Chongqing Municipal Health Commission 2020FYYX045. Funding agency contribute to the publication of paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. XT1 and Dr. GL contributed equally to this work, including data collection, manuscript drafting and literature research. Dr. XT2 and Dr. JX contributed to the patient management. Dr. CL performed the operations of the patients. Dr. YJ contributed to the clinical treatment and manuscript revision for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from both the patients for publication of identifying images or other personal or clinical details of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, X., Liu, G., Tan, X. et al. Solitary multicystic lesion lung cancer: two case reports and review of the literature. BMC Pulm Med 21, 368 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01729-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01729-7