Abstract

Background

While lung transplant (LTX) can be an effective therapy to provide the survival benefit in selected populations, post-transplant outcome in LTX recipients with bronchiectasis other than cystic fibrosis (CF) has been less studied. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, often associated with exacerbations in bronchiectasis, is the most common micro-organism isolated from LTX recipients. We aimed to see the outcomes of patients with bronchiectasis other than CF after LTX and seek the risk factors associated with pre- and post-transplant Pseudomonas status.

Methods

Patients who underwent LTX at Tohoku University Hospital between January 2000 and December 2020 were consecutively included into the retrospective cohort study. Pre- and post-transplant prevalence of Pseudomonas colonization between bronchiectasis and other diseases was reviewed. Post-transplant outcomes (mortality and the development of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD)) were assessed using a Cox proportional hazards and time-to-event outcomes were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method.

Results

LTX recipients with bronchiectasis experienced a high rate of pre- and post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization compared to other diseases with statistical significance (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively). Nevertheless, long-term survival in bronchiectasis was as great as non-bronchiectasis (Log-rank p = 0.522), and the bronchiectasis was not a trigger for death (HR 1.62, 95% CI 0.63–4.19). On the other hand, the chance of CLAD onset in bronchiectasis was comparable to non-bronchiectasis (Log-rank p = 0.221), and bronchiectasis was not a predictor of the development of CLAD (HR 1.88, 95% CI 0.65–5.40).

Conclusions

Despite high prevalence of pre- and post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization, the outcome in LTX recipients with bronchiectasis other than CF was comparable to those without bronchiectasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Bronchiectasis is a heterogeneous airway disease characterized by irreversible dilatation of bronchial lumen leading to chronic respiratory symptoms and recurrent pulmonary infections with a reduction of lung function [1, 2]. Because of poor outcome in the severe form of bronchiectasis, lung transplant (LTX) is an effective therapy to prolong the survival in the selected population [3, 4]. Despite its heterogenous etiology, cystic fibrosis (CF) is a clinically relevant cause of bronchiectasis and a common indication for LTX worldwide and its outcome following LTX has been successively reported. However, the post-transplant outcomes from bronchiectasis other than CF has been less studied. This may be because bronchiectasis other than CF has been considered as having less favorable outcomes and more complicated postoperative courses due to older age compared to CF [5, 6]. Additionally, some studies combined two bronchiectasis subgroups in a single cohort [7, 8], resulting in fewer reports regarding bronchiectasis other than CF.

CF is a common inherited disorder among Caucasians with an estimated incidence of 1 in 4500 live births in Western Europe and 1 in 4000 in North America [9], while in Japanese populations it is extremely rare, reported 1 in 350,000 [10]. Thus, further understanding post-transplant outcomes in bronchiectasis other than CF is needed to provide LTX for patients with advanced bronchiectasis in Japan.

Progression of bronchiectasis can be caused by a variety of pathogenic micro-organisms [11]. While the clinical significance of non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) and Aspergillus is becoming recognized and their prevalence is increasing worldwide in bronchiectasis [12, 13], Pseudomonas aeruginosa is the most commonly isolated pathogen and related to a severe form as well as frequent exacerbations in bronchiectasis [1, 3, 14]. Similarly, Pseudomonas is the most frequently isolated pathogen from lung grafts as well as the sinus in LTX recipients with CF [15,16,17], which was currently considered as a risk factor for the worse post-transplant outcomes [18,19,20].

We thus hypothesized that the patients with bronchiectasis other than CF who underwent LTX likely harbor the more common Pseudomonas prior to transplantation and consequently the recipients could retain a high prevalence of Pseudomonas colonizing their airways after surgery, resulting in a higher incidence of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD) and mortality than other disorders. We therefore aimed to see the outcomes of patients with bronchiectasis other than CF after LTX and to seek the risk factors associated with pre- and post-operative Pseudomonas status.

Materials and methods

Patient population and study objectives

Patients who underwent LTX at Tohoku University Hospital (TUH) between January 1st, 2000 and December 31st, 2020 were consecutively included in the retrospective cohort, with follow-up extending to December 31st, 2020 (Fig. 1). LTX recipients who were younger than 18 years old or re-transplanted were excluded from the study. Baseline data were obtained at the time of LTX, and follow-up data were collected at month 1, 2, 3 and 6, and annually post-transplant, or when clinically indicated. Surveillance bronchoscopy was not routinely scheduled in our program but performed when clinically needed. Immunosuppression, histocompatibility testing and overall management after transplantation have been previously described [21,22,23]. All LTX recipients received valganciclovir 900 mg daily for CMV prophylaxis for 1 year after transplantation and have been on a life-long prophylaxis with trimethoprim 80 mg-sulfamethoxazole 400 mg and itraconazole 200 mg (transplanted between 2008 and 2018) or voriconazole adjusted to target a trough concentration between 1 and 2 µg/ml (transplanted after 2018).

Study objectives

The primary objective of the study was to see the mortality and the incidence of CLAD among LTX recipients with or without bronchiectasis and assess their risk factors. The secondary objective was to review the pre- and post-transplant prevalence of Pseudomonas colonization between bronchiectasis and other diseases, and seek the risk factors associated with its colonization after LTX. The tertiary objective was to observe the incidence of other pathogens including NTM and Aspergillus in those populations.

Definition of variables

Radiographic morphology of bronchiectasis was assessed by two experienced respirologists and categorized according to a previous report [24]. Chronic sinusitis was defined by at least two cardinal symptoms from the following: facial discomfort, hyposmia, nasal drainage, and nasal obstruction over 12 weeks and radiographic evidence of opacification in the paranasal sinuses through computed tomography (CT) [25]. CLAD was defined as ≥ 20% of irreversible drop in FEV1 from the baseline which was confirmed two times 3 months after LTX [26].

Microbiological assessment

Sputum, induced sputum, or bronchial washing fluid (sputum hereafter) was collected from LTX recipients at the monthly follow-up clinic or the annual hospital visit, or when respiratory symptoms were newly developed or pulmonary function was deteriorated. Sputum was sent to the microbiology laboratory at TUH, assessed for the morphologic characterization by Gram staining and acid-fast bacillus (AFB)- fluorescence microscopy, and cultured into 7 different media including sheep-blood, chocolate and Drigalski lactose for bacteria, Sabouraud and CHROMagar Candida™ (Kanto Kagaku CO. Inc., Tokyo, Japan) for fungus and AFB liquid broth and solid culture for mycobacteria. Bacteria were incubated for 48 h, filamentous fungus for 14 days and mycobacteria for 6 weeks. Microorganism was identified by the matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry. The threshold value for the positive culture of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was set for ≥ 103 colony forming units (CFU)/mL [27]. Pseudomonas was considered colonization when cultured twice at least 3 months apart over a 12-month period [14]. Non-aeruginosa Pseudomonas was excluded from Pseudomonas colonization. Two positive cultures of NTM from sputum was regarded colonization [28], while Aspergillus colonization was defined by one positive culture of Aspergillus species from sputum [29]. Cases of apparent or sub-clinical infection due to Pseudomonas, NTM or Aspergillus were included in the colonization.

Statistical analysis

The variables between bronchiectasis and non-bronchiectasis at the time of LTX were shown in percentage or medians (interquartile range (IQR)) as appropriate, and the difference in baseline data were assessed with chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categoric variables and Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables. The cross-sectional analysis for the post-transplant outcomes were carried out based on the date on December 31st, 2020. Risk factors associated with post-transplant events were assessed using a Cox proportional hazards model. Variables considered a priori to be clinically important (age, sex, LTX procedure, LTX indication and ischemic time) and known bronchiectasis risk factors (history of pre-transplant Pseudomonas colonization and chronic sinusitis) were selected for analysis. Only univariate analysis was shown in result due to the small sample size of patients with bronchiectasis, while multivariate analysis was shown in supplemental data. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to model time-to-event outcomes, and differences across groups were calculated with the log-rank test. Unadjusted survival analyses were performed to avoid overfitting due to the small sample size. p Values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses and graph generation were performed with GraphPad Prism 6.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA) and StatPlus:macLE (AnalystSoft; Walnut, California, US).

Results

Study population and characteristics of patients with bronchiectasis

One hundred and twenty-four patients who received a LTX between January 2000 and December 2020 were serially included for analysis (Fig. 1). Median age was 45 (IQR 34-51) and 38.7% were male (Table 1). Single lung transplant was the most common surgical procedure at 67/124 (54.0%), and obstructive lung disease was the major LTX indication in 51/124 (39.5%). Chronic sinusitis was found in 19/124 (15.3%) of the recipients, connective tissue disease in 14/124 (11.3%) and history of pre-transplant Pseudomonas colonization in 13/124 (10.5%). Patients were divided into bronchiectasis (n = 13) and non-bronchiectasis (n = 111) groups. There was no difference in age and gender between groups, yet a bilateral lung transplant procedure was the more common LTX procedure in bronchiectasis as compared to non-bronchiectasis (p < 0.0001). Chronic sinusitis and Pseudomonas colonization were more readily found in patients with bronchiectasis compared to those without bronchiectasis (p < 0.0001 and p < 0.0001, respectively). No other difference was found in pre-transplant comorbidities between the patients with and without bronchiectasis. According to LTX procedure, ischemic time in bronchiectasis was longer than non-bronchiectasis (p = 0.002). Suppurative lung disease, herein synonymously bronchiectasis, accounted for 10.5% (13/124) of LTX indication in our center, and its etiology is shown in Table 2. Diffuse pan-bronchiolitis (DPB) was the major underlying disease at 5/13 (38.5%), followed by unknown etiology at 4/13 (30.8%). Two patients had bronchiectasis due to systemic inflammatory diseases and both were diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis. No CF patients underwent LTX in our center. Bronchiectasis progressed up until the recipients received LTX, at which point the thoracic CT demonstrated cystic changes in most patients (11/13, 84.6%).

Outcomes of LTX recipients with bronchiectasis

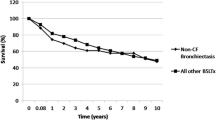

Time to event outcomes between bronchiectasis (n = 13) and non-bronchiectasis (n = 111) is shown in Fig. 2. There was no survival difference in the overall study cohort between groups (Log-rank p = 0.522). Although the probability of CLAD development in bronchiectasis was not statistically higher than non-bronchiectasis (Log-rank p = 0.221), there seemed to be numerical differences between groups. On the other hand, the incidence of Pseudomonas colonization was significantly greater in bronchiectasis group than non-bronchiectasis (Log-rank p < 0.001). The chances of NTM colonization were more likely in bronchiectasis (Log-rank p = 0.042) rather than non-bronchiectasis, while that of Aspergillus was not different between the groups (Log-rank p = 0.135). The same analysis using Kaplan–Meier method was performed for every LTX category, including restrictive lung disease (n = 30), vascular (n = 27), obstructive (n = 51) versus suppurative (n = 13), shown in Fig. 3. The survival rate in bronchiectasis was not significantly different among the four categories (Log-rank p = 0.157) despite the restrictive lung disease group seemingly having a lower rate. There was no difference in time to CLAD onset among transplant categories (Log-rank p = 0.250), yet the cumulative CLAD probability in the vascular group was apparently lower than the suppurative group. In contrast, the incidence of Pseudomonas colonization after LTX was more likely in the suppurative group than other categories (Log-rank p = 0.01). The chances of post-transplant NTM colonization were not remarkable among LTX categories (Log-rank p = 0.195), whereas Aspergillus colonization was more seen in the suppurative group than the others in a portion of the study periods (Log-rank p = 0.022). The post-transplant outcomes in bronchiectasis and non-bronchiectasis were cross-sectionally analyzed (Table 3). The fraction of death (38.5% vs 27.0%, p = 0.515) and time to death (25 months (IQR 3–85) vs 14 months (IQR 1–58), p = 0.775) were not significant between groups. The leading cause of death on LTX recipients at THU was infection, responsible for 60% (3/5) in bronchiectasis and 23.3% (7/30) in non-bronchiectasis without difference in groups (p = 0.643).

Kaplan–Meier analysis to model time-to-event outcomes in lung transplant recipients with/without bronchiectasis. A Percent survival, B cumulative incidence of CLAD probability, C cumulative prevalence of Pseudomonas colonization, D cumulative prevalence of NTM colonization and E cumulative prevalence of Aspergillus colonization. The number of patients at risk was depicted below the x-axis (post-transplant months). BE; bronchiectasis, CLAD; chronic lung allograft dysfunction, NTM; non-tuberculous mycobacteria

Kaplan–Meier analysis to model time-to-event outcomes in lung transplant recipients among 4 transplant categories. A Percent survival, B cumulative incidence of CLAD probability, C cumulative prevalence of Pseudomonas colonization, D cumulative prevalence of NTM colonization and E cumulative prevalence of Aspergillus colonization. The number of patients at risk was depicted below the x-axis (post-transplant months). BE; bronchiectasis, CLAD; chronic lung allograft dysfunction, NTM; non-tuberculous mycobacteria

Risk factors associated with outcomes

Risk factors for each outcome in univariable analysis using a Cox hazard model are shown in Table 4. As the two lobes were implanted into bilateral chest cavities, the living-donor transplant was categorized as bilateral transplant in the analysis. Bronchiectasis (n = 13), compared to non-bronchiectasis (n = 111), was not associated with mortality in the overall study cohort (HR 1.62, 95% CI 0.63–4.19), yet age was a risk factor to death (HR 1.03, 95% CI 1.01–1.08). Risk factors for the development of CLAD were also analyzed, showing the recipient age at the LTX (HR 1.04, 95% CI 1.01–1.08) and chronic sinusitis (HR 2.56, 95% CI 1.10–5.99) becoming predictors of CLAD onset but bronchiectasis was not associated with its development (HR 1.88, 95% CI 0.65–5.40). Similar to the finding shown in the Kaplan–Meier method, bronchiectasis was associated with post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization (HR 4.30, 95% CI 1.88–9.85). Additionally, the LTX procedure (bilateral vs single, HR 2.21, 95% CI 1.01–4.76), history of pre-transplant Pseudomonas colonization (HR 3.77, 96% CI 1.65–8.62) and chronic sinusitis (HR 2.75, 95% CI 1.21–6.28) demonstrated statistical significance for increased risk for post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization. There was a trend of NTM colonization in LTX recipients with bronchiectasis (HR 3.01, 95% CI 0.97–9.32) and chronic sinusitis (HR 2.69, 95% CI 0.94–97.69) in the univariable analysis but not a statistically higher chance. Although bronchiectasis was not a predictor of post-transplant Aspergillus colonization (HR 2.24, 95% CI 0.75–6.70), history of pre-transplant Pseudomonas colonization could be related to its isolation (HR 2.91, 95% CI 1.05–8.01).

Discussion

As previously reported that Pseudomonas is frequently isolated in patients with bronchiectasis and LTX recipients [1, 3, 18, 30, 31], our study demonstrated that LTX recipients with bronchiectasis other than CF experienced high rate of pre- and post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization with statistical significance. Nevertheless, long-term survival in the bronchiectasis group was as great as the non-bronchiectasis group or other disease categories, and bronchiectasis was not an independent risk for CLAD development. Our results were consistent with other analyses that survival rate was similar between bronchiectasis (n = 42) versus other diseases requiring bilateral LTX in UK [32] and between bronchiectasis with CF (n = 42) and non-CF (= 33) in Israel [6] although isolation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa was common in those populations. In view of these considerations, it is conceivable that bronchiectasis, despite high prevalence of pre- and post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization, is not a prominent risk factor for the post-transplant mortality and the development of CLAD. However, a contradictory outcome was reported from a LTX center in Australia [33], where lower 5-year survival and more hospital admission were shown in bronchiectasis other than CF. As numerous confounding factors affect the outcomes after transplantation in this population, multivariate analysis would be helpful for further understanding of the risks in those population. To this end, the study including a large number of patients should be planned to see which variables among the individuals with bronchiectasis would have an impact on the post-transplant outcomes.

Given their ubiquitous presence in many environments, both NTM and Aspergillus are also frequently identified from LTX recipients but considered more unfavorably due to their pathogenic roles, and currently regarded as probable risk factors for the poor outcomes among LTX recipients [34,35,36,37]. A higher cumulative incidence of post-transplant NTM colonization was found in bronchiectasis compared to other diseases (Log-rank 0.042), whereas the post-transplant prevalence of Aspergillus was high in the suppurative disease rather than the other categories (Log-rank p = 0.022). In view of the graft and native lungs that accompany anatomic abnormalities and are constantly exposed to ubiquitous environmental micro-organisms, superinfection or double- or triple-isolation of Pseudomonas, NTM and Aspergillus is an expected consequence after LTX. However, pathogenic roles of those organisms are not clearly defined because of complicated pathogen-host interactions especially under immune-suppressants and the heterogeneous pathogenesis of bronchiectasis. Furthermore, microbiological assessment of the pathogenic aspect of those organisms is challenging as there are no validated biomarkers to distinguish infection from colonization and also the majority of LTX recipients is routinely or repeatedly on anti-microbial agents for prophylaxis or treatment. With our analysis, the post-transplant prevalence of Pseudomonas, NTM and Aspergillus was high in LTX recipients with bronchiectasis. Nevertheless, an extended study to see how those micro-organisms influence the graft function and how anti-microbial agents, together with immunosuppression, play roles in such population are needed.

A prominent feature of bronchiectasis other than CF is an involvement of chronic sinusitis with little known etiology [38]. Sinusitis is considered a reservoir for allograft colonization of micro-organisms after LTX [16, 17]. In our assessment, chronic sinusitis was an independent risk factor for CLAD (HR 2.56, 95% CI 1.10–5.99) and post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization (HR 2.75, 95% CI 1.21–6.28). In previous studies, sinus surgery led to an improvement in pulmonary function in LTX recipients with sinusitis [39] and reduced Pseudomonas colonization in CF-LTX recipients [15]. Importantly, there was a high correlation between pre-transplant sinus and post-transplant BAL cultures for Pseudomonas [17] and the same isolates were found in nasal lavage and BAL performed on the same visit in CF patients [16]. With those features in mind, it should be reasonable to consider the early intervention of sinus surgery prior to LTX or in the early phase after LTX, which may be capable of preventing from the development of CLAD in the specific population with chronic sinusitis. Yet, different analyses demonstrated little impact of pre-transplant sinus surgery on post-transplant recolonization of Pseudomonas in a CF population [40]. Thus, our next challenge is to consider the clinical trial to prospectively intervene whether sinus surgery affect the transplant outcome in patients with sinusitis.

Nonetheless, our study must be interpreted with caution and a number of limitations should be considered. First, we have insufficient sample size for further analysis. In order to seek the risk factors for outcomes, there were variables that needed to be included for the analysis, such as bronchiectasis, pre-transplant Pseudomonas colonization and chronic sinusitis, with which multivariate analysis should be performed. Due to shortage of the bronchiectasis patients (n = 13), the multivariate cox hazard model showed a wide confidence interval (Additional file 1: Supplemental data) and was not worth documenting. Despite the univariate analysis that lacks adjustments for comparisons or power for multivariate analysis, comparable survival rates and a high rate of pre- and post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization in bronchiectasis were evident from our study. A multicenter study including a large number of patients with bronchiectasis for analysis would be beneficial in seeing the outcome calculated on the basis of a multivariate analysis. Second, we were unable to analyze whether the post-transplant Pseudomonas led to the CLAD onset, or vice versa. An etiology between post-transplant Pseudomonas colonization and CLAD development is a chicken-or-egg problem and remains unexplored, yet colonized Pseudomonas was partially or somewhat considerably associated with developing or worsening CLAD [18, 19, 30, 31]. To understand whether the duration of one variable is a risk factor for another variable is complicated when it may occur at some time after LTX. Apart from causality that has never been proven through observational studies, the recent study from clinical practice demonstrated Pseudomonas eradication after LTx improved CLAD-free and graft survival and maintained pulmonary function [31]. This kind of intervention is a means to prove its complicated relationship and a feasible approach to seek how best we could provide better outcome among individuals with bronchiectasis after LTX. In addition to those above analyses, it would be intriguing to see whether pre- and post-transplant Pseudomonas are the same strains by genotyping [41] and how multi-drug resistant strains affect the outcome [42]. Finally, additional analysis in the details of post-transplant complications will be needed for a better understanding those populations. CLAD was determined in 4 LTX recipients with bronchiectasis other than CF in the study period, of which 2 cases were obstructive and the others restrictive in CLAD phenotype. It cannot be conclusive from such a small number of CLAD cases whether they tended to show which phenotype of allograft loss. On the other hand, a recent study demonstrated bronchiectasis rather than CF had higher rate of CLAD with infectious features than other diseases [33]. Given higher prevalence of chronic sinusitis and chances of Pseudomonas colonization, infectious exacerbations could be more commonly seen in LTX recipients with bronchiectasis other than CF. As the lack of those data in our study, the next challenge is to investigate the post-transplant complications in those individuals in a large-scale analysis.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the long-term outcome in LTX recipients with the underlying disease of bronchiectasis other than CF, a representative of the suppurative lung disease in Japan, was comparable to those without bronchiectasis. Our investigation also demonstrated a similar ratio of CLAD development despite a higher chance of Pseudomonas colonization in bronchiectasis compared to other diseases or categories. Although multivariate analysis will be needed for the further understanding of risk factors for post-transplant outcomes, this study will be fundamental to future trials for individuals with bronchiectasis requiring LTX.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CF:

-

Cystic fibrosis

- CLAD:

-

Chronic lung allograft dysfunction

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- LTX:

-

Lung transplant

- NTM:

-

Non-tuberculous mycobacteria

References

Polverino E, Goeminne PC, McDonnell MJ, Aliberti S, Marshall SE, Loebinger MR, et al. European Respiratory Society guidelines for the management of adult bronchiectasis. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700629.

Bush A, Floto RA. Pathophysiology, causes and genetics of paediatric and adult bronchiectasis. Respirology. 2019;24:1053–62.

Hill AT, Sullivan AL, Chalmers JD, De Soyza A, Stuart Elborn J, Andres Floto R, et al. British thoracic society guideline for bronchiectasis in adults. Thorax. 2019;74(Suppl 1):1–69.

Weill D, Benden C, Corris PA, Dark JH, Davis RD, Keshavjee S, et al. A consensus document for the selection of lung transplant candidates: 2014—an update from the Pulmonary Transplantation Council of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2015;34:1–15.

Yusen RD, Edwards LB, Dipchand AI, Goldfarb SB, Kucheryavaya AY, Levvey BJ, et al. The registry of the international society for heart and lung transplantation: thirty-third adult lung and heart-lung transplant report—2016; focus theme: primary diagnostic indications for transplant. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2016;35:1170–84.

Rusanov V, Fridman V, Wille K, Kramer MR. Lung transplantation for cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a single-center experience. Transplant Proc. 2019;51:2029–34.

Hirama T, Singer LG, Brode SK, Marras TK, Husain S. Outcomes of a peri- and postoperative management protocol for non-TB mycobacteria in lung transplant recipients. Chest. 2020;158:523–8.

Raskin J, Vanstapel A, Verbeken EK, Beeckmans H, Vanaudenaerde BM, Verleden SE, et al. Mortality after lung transplantation: a single-centre cohort analysis. Transpl Int. 2020;33:130–41.

Scotet V, L’hostis C, Férec C. The changing epidemiology of cystic fibrosis: Incidence, survival and impact of the CFTRGene discovery. Genes (Basel). 2020;11:589.

Yamashiro Y, Shimizu T, Oguchi S, Shioya T, Nagata S, Ohtsuka Y. The estimated incidence of cystic fibrosis in Japan. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;24:544–7.

Richardson H, Dicker AJ, Barclay H, Chalmers JD. The microbiome in bronchiectasis. Eur Respir Rev. 2019;28:190048.

Chotirmall SH, Martin-Gomez MT. Aspergillus species in bronchiectasis: challenges in the cystic fibrosis and non-cystic fibrosis airways. Mycopathologia. 2018;183:45–59.

Máiz L, Girón R, Olveira C, Vendrell M, Nieto R, Martínez-García MA. Prevalence and factors associated with nontuberculous mycobacteria in non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a multicenter observational study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-016-1774-x.

Finch S, McDonnell MJ, Abo-Leyah H, Aliberti S, Chalmers JD. A comprehensive analysis of the impact of pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization on prognosis in adult bronchiectasis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1602–11.

Vital D, Hofer M, Benden C, Holzmann D, Boehler A. Impact of sinus surgery on pseudomonal airway colonization, bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and survival in cystic fibrosis lung transplant recipients. Respiration. 2013;86:25–31.

Morlacchi LC, Greer M, Tudorache I, Blasi F, Welte T, Haverich A, et al. The burden of sinus disease in cystic fibrosis lung transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2018;20:1–11.

Choi KJ, Cheng TZ, Honeybrook AL, Gray AL, Snyder LD, Palmer SM, et al. Correlation between sinus and lung cultures in lung transplant patients with cystic fibrosis. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2018;8:389–93.

Botha P, Archer L, Anderson RL, Lordan J, Dark JH, Corris PA, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization of the allograft after lung transplantation and the risk of bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Transplantation. 2008;85:771–4.

Verleden SE, Ruttens D, Vandermeulen E, Vaneylen A, Dupont LJ, Van Raemdonck DE, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and restrictive allograft syndrome: do risk factors differ? Transplantation. 2013;95:1167–72.

Glanville AR. Pseudomonas and risk factor mitigation for chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:22–4.

Kumata S, Hirama T, Watanabe Y, Oishi H, Niikawa H, Akiba M, et al. The fraction of sensitization among lung transplant recipients in a transplant center in Japan. BMC Pulm Med. 2020;20:256.

Katahira M, Hirama T, Eba S, Suzuki T, Notsuda H, Oishi H, et al. Impact of postoperative continuous renal replacement therapy in lung transplant recipients. Transplant Direct. 2020;6:e562.

Nikkuni E, Hirama T, Hayasaka K, Kumata S, Kotan S, Watanabe Y, et al. Recovery of physical function in lung transplant recipients with sarcopenia. BMC Pulm Med. 2021;21:124.

Juliusson G, Gudmundsson G. Diagnostic imaging in adult non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis. Breathe. 2019;15:190–7.

Sedaghat AR. Chronic Rhinosinusitis. In: Durand ML, Deschler DG, editors. Infections of the ears, nose, throat, and sinuses. Cham: Springer; 2018. p. 155–68.

Verleden GM, Glanville AR, Lease ED, Fisher AJ, Calabrese F, Corris PA, et al. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: definition, diagnostic criteria, and approaches to treatment—a consensus report from the Pulmonary Council of the ISHLT. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38:493–503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2019.03.009.

Woodhead M, Blasi F, Ewig S, Huchon G, Ieven M, Leven M, et al. Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:1138–80.

Daley CL, Iaccarino JM, Lange C, Cambau E, Wallace RJ, Andrejak C, et al. Treatment of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease: an official ATS/ERS/ESCMID/IDSA clinical practice guideline: executive summary. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:e1-36.

Ullmann AJ, Aguado JM, Arikan-Akdagli S, Denning DW, Groll AH, Lagrou K, et al. Diagnosis and management of Aspergillus diseases: executive summary of the 2017 ESCMID-ECMM-ERS guideline. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24:e1-38.

Vos R, Vanaudenaerde BM, Geudens N, Dupont LJ, Van Raemdonck DE, Verleden GM. Pseudomonal airway colonisation: risk factor for bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome after lung transplantation? Eur Respir J. 2008;31:1037–45.

De Muynck B, Van Herck A, Sacreas A, Heigl T, Kaes J, Vanstapel A, et al. Successful Pseudomonas aeruginosa eradication improves outcomes after lung transplantation: a retrospective cohort analysis. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001720.

Birch J, Sunny SS, Hester KLM, Parry G, Kate Gould F, Dark JH, et al. Outcomes of lung transplantation in adults with bronchiectasis. BMC Pulm Med. 2018;18:1–9.

Kennedy J, Walker A, Ellender CM, Steinfort K, Martin C, Smith C, et al. Outcomes of non-cystic fibrosis related bronchiectasis post lung transplantation. Intern Med J. 2021.

Friedman DZP, Cervera C, Halloran K, Tyrrell G, Doucette K. Non-tuberculous mycobacteria in lung transplant recipients: prevalence, risk factors, and impact on survival and chronic lung allograft dysfunction. Transpl Infect Dis. 2020;22:1–7.

Shah SK, McAnally KJ, Seoane L, Lombard GA, LaPlace SG, Lick S, et al. Analysis of pulmonary non-tuberculous mycobacterial infections after lung transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18:585–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/tid.12546.

Knoll BM, Kappagoda S, Gill RR, Goldberg HJ, Boyle K, Baden LR, et al. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial infection among lung transplant recipients: a 15-year cohort study. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14:452–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1399-3062.2012.00753.x.

Aguilar CA, Hamandi B, Fegbeutel C, Silveira FP, Verschuuren EA, Ussetti P, et al. Clinical risk factors for invasive aspergillosis in lung transplant recipients: Results of an international cohort study. J Hear Lung Transplant. 2018;37:1226–34.

Handley E, Nicolson CH, Hew M, Lee AL. Prevalence and clinical implications of chronic rhinosinusitis in people with bronchiectasis: a systematic review. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7:2004–12.

Ramos BF, De Rezende Pinna F, Campos SV, Afonso Júnior JE, De Oliveira Braga Teixeira RH, Carraro RM, et al. Assessment of pulmonary function before and after sinus surgery in lung transplant recipients. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2018;22:157–60.

Leung M-K, Rachakonda L, Weill D, Hwang PH. Effects of sinus surgery on lung transplantation outcomes in cystic fibrosis. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:192–6.

Syed SA, Whelan FJ, Waddell B, Rabin HR, Parkins MD, Surette MG. Reemergence of lower-airway microbiota in lung transplant patients with cystic fibrosis. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13:2132–42.

Aguado JM, Silva JT, Fernández-Ruiz M, Cordero E, Fortún J, Gudiol C, et al. Management of multidrug resistant Gram-negative bacilli infections in solid organ transplant recipients: SET/GESITRA-SEIMC/REIPI recommendations. Transplant Rev. 2018;32:36–57.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

The collection, analysis, and interpretation of data were supported in a part by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research C (20K08509) and Research Fellow (21J21515) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. No additional external funding was received for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TH is the guarantor of this manuscript, responsible for statistical analysis and has full access to all of the data in the study. FT, HN, TW, YW and HO gathered information from the medical chart and the database and contributed the data analysis and interpretation. YO had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. In light of the retrospective design, the requirement of informed consent was waived and the study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (Institutional Review Board number 2019-1-766). We disclosed information on the implementation of the research and ensured the opportunity for research subjects to refuse participation by posting the information disclosure materials approved by the Ethics Committee on the website of the Graduate School of Medicine, Tohoku University.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1

. Risk factors for mortality, development of CLAD and Pseudomonas colonization from multivariate Cox model.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hirama, T., Tomiyama, F., Notsuda, H. et al. Outcome and prognostic factors after lung transplantation for bronchiectasis other than cystic fibrosis. BMC Pulm Med 21, 261 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01634-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01634-z