Abstract

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic interstitial lung disease with unclear pathogenesis. IPF is considered as a risk factor for lung cancer. Compared to other lung cancers, small-cell lung cancer (SCLC) has a lower incidence, but has a more aggressive course. Patients with IPF and SCLC have a lower survival rate, more difficult treatment, and poorer prognosis.

Case presentation

Case 1 was of a 66-year-old man with IPF for 5 years, who was admitted to our hospital for dyspnea. Case 2 was of a 68-year-old woman, who presented with chest pains, cough, and dyspnea. Both patients had extremely poor lung function. High-resolution computed tomography and pathology revealed that both patients had IPF and SCLC. Chemotherapy comprising nedaplatin (80 mg/m2) and etoposide (100 mg for 5 days) was initiated for both patients. Antifibrotic agents were continued during the chemotherapeutic regimen. Both patients showed improvement in their condition after treatment.

Conclusion

The favorable outcomes in these 2 cases suggests that chemotherapy is worth considering in the management of patients having SCLC and IPF with poor lung function.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a chronic lung disease that causes irreversible decline in lung function [1]. The changes accompanying IPF severely affect the quality of life of the patients. Furthermore, IPF is associated with a high risk of lung cancer [2]. SCLC is a disease that is generally detected in its later stages, although it is sensitive to chemotherapy. However, in patients with IPF who subsequently develop SCLC, the prognosis is poor. Currently, limited data are available on the treatment of such patients and reports on the successful treatment of such cases are scarce. However, chemotherapy carries the risk of acute exacerbations in IPF patients and contributes to an increased risk of mortality. Therefore, the choice of chemotherapy should be made after careful consideration of the benefits and risks [3]. Herein, we describe two cases of successful treatment in patients with IPF as well as SCLC.

Case presentation

Case 1

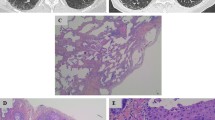

The patient was a 66-year-old man who presented with dyspnea and cough and was referred to the Second Hospital of Jilin University 5 years ago. The patient was a retired worker with a 40 pack-year history of smoking and no history of other diseases. HRCT scan of the chest revealed that the patient had masses in both lungs, with fibrous stripes and diffuse subpleural reticular pattern, which were indicative of IPF (Fig. 1a, b). Lung function tests showed a substantial decrease in the diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide (DLCO; < 60%), while blood gas analysis showed reduced levels of partial pressure of oxygen (PaO2). Treatment with glucocorticoids and pirfenidone led to improvement of the symptoms. With regular treatment, the patient’s condition continued to remain stable, as confirmed by a follow-up chest HRCT performed 5 years later. However, the follow-up scan revealed a newly developed, irregular mass in the right upper lobe and enlargement of the anterior trachea and posterior vena caval groups of lymph nodes; the lower lobes did not show any changes on either side (Fig. 1c, d). The patient then underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy for retrieval of a tissue sample. Pathological examination of the sample revealed SCLC in the superior lobe of the right lung (Fig. 1e, f).

a, b Chest HRCT scan showed a mass with fibrous stripes and patchy shadows in the lower lobe at the age of 61. c, d Follow-up Chest HRCT scan at the age of 66 years showed that there were no changes in both the lower lobes, but there was a new space-occupying lesion in the right lung. e, f Pathological examination (H&E staining, original magnification 100×, 400×) of bronchoscopy sample revealed small-cell lung cancer. G,H, Chest HRCT scan after chemotherapy showed reduction of the shadow in the upper lobe of the right lung

A chemotherapeutic regimen comprising nedaplatin (80 mg/m2) and etoposide (100 mg for 5 days) was then initiated. However, during the chemotherapy, the administration of antifibrotic agents was continued. After 4 courses of treatment, marked reduction of the tumor was observed. A repeat thoracic CT scan revealed reduction in the size of the shadow in the upper right lung and significant decrease in the size of the metastatic lymph nodes in the anterior tracheal and posterior vena caval groups of lymph nodes; however, there was no visible decrease in the severity of IPF (Fig. 1g, h). Thus, we concluded that the treatment was effective and safe, and we recommend that chemotherapy be continued, depending on whether the patient can tolerate and afford it. We followed up the patient three months later. The patient’s vital signs were stable, and there were no instances of subsequent infections or other complications. Therefore, we concluded that chemotherapy was relatively safe and the patient could benefit from chemotherapy.

Case 2

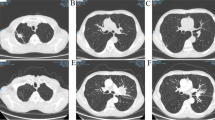

A 68-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital for the management of chest pains since eight days with no apparent causes. The patient had a 30 pack-year history of smoking and denied having a history of any other diseases. Chest pain was accompanied by cough and dyspnea, which were aggravated after exercise. She had poor lung function (DLCO; < 30%), and blood gas analysis revealed respiratory failure. Chest HRCT scans showed fibrotic changes in the lower lobes of both lungs and high-density shadows in the upper lobe of the left lung with obstructive atelectasis. Further, enlargement of the mediastinal lymph nodes was also noted (Fig. 2a, b). For the identification of the cause of atelectasis, the patient underwent fiberoptic bronchoscopy. The results of pathological examination of the extracted tissue sample were indicative of SCLC. Chemotherapy with intravenous nedaplatin (80 mg/m2) and etoposide (100 mg for 5 days) was initiated. During the chemotherapy, treatment with glucocorticoids and N-acetylcysteine was continued in order to control the symptoms and prevent the progression of fibrosis. After 6 cycles of chemotherapy, the patient’s symptoms were relieved. Follow-up CT scan revealed a reduction in the extent of atelectasis in the left upper lobe, reduction in the size of the mass shadow, and absence of mediastinal lymph node enlargement (Fig. 2c, d). IPF remained stable. The follow-up was conducted for one year. She was in good condition with no severe dyspnea and no complications such as infection. We conclude that the patient benefited greatly from the chemotherapy.

Discussion and conclusion

IPF is a severe pulmonary fibrotic disease that entails a high risk of LC; to date, its etiopathogenesis remains elusive [4]. The incidence of LC in IPF patients is relatively high, at 13.54% [5]. Therefore, it is imperative that IPF patients be monitored for the development of LC. Studies have shown some similarities in the pathological features of IPF and LC, including proliferation, immune dysregulation, cell senescence, and resistance to apoptosis [6, 7]. In addition, epithelial changes associated with pulmonary fibrosis may be involved in the development of lung cancer [8]. Smoking is an independent risk factor for lung cancer in IPF patients [9]. Therefore, smokers with IPF, in particular, should be closely monitored for signs of lung cancer. Since treatment measures such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy carry the risk of acute exacerbation of IPF and increased mortality, the management of LC in IPF patients is highly challenging. Therefore, the severity of IPF in each patient should be carefully assessed [10]. For patients with IPF, acute exacerbation is a life-threatening event [11]. Non-SCLC has been reported to be commonly associated with IPF, and it is generally treated with nintedanib and pirfenidone [12]. Compared to other cancer types, SCLC has a lower incidence in patients with IPF, but it has a more invasive course and shorter survival [13, 14]. A recent meta-analysis revealed that among IPF patients with lung cancer, the proportion of those with SCLC was 20.48% [5]. In the absence of treatment, patients with SCLC rapidly develop acute exacerbation and have poor survival [15]. However, SCLC is sensitive to chemotherapy. Therefore, chemotherapy may still be a good treatment option for IPF patients with SCLC. Since there have been no adequate clinical trials, the ideal chemotherapy regimen for patients with IPF and SCLC, which can destroy tumor cells without influencing IPF, is yet to be identified.

In Case 1, the patient had a history of IPF since 5 years and insisted on continuing his medication to maintain stability of his condition. In Case 2, IPF and SCLC were detected simultaneously, but the longer history of IPF could not be excluded. The coexistence of IPF and SCLC compromises pulmonary function and may lead to respiratory failure, as seen in Case 2. According to the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG), chemotherapy poses significant risk in patients with IPF. Therefore, before initiation of the treatment, both the patients as well as their family members were explained in detail about the risks and benefits of the treatment, and consent for the treatment was obtained. In both of our cases, the patients benefited from chemotherapy, without the exacerbation of IPF. Adverse events of chemotherapy were defined as low (i.e., grades 1–2), as per the CTCAE v5.0.

Etoposide, in combination with platinum, is a commonly used chemotherapeutic regimen with fairly good treatment outcomes. Nedaplatin is a second-generation cisplatin, with a mechanism of action similar to that of cisplatin, but lower nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity; additionally, it does not show complete cross-resistance with any other chemotherapeutic agents used in combination with platinum [16]. Etoposide, as a cycle-specific chemotherapeutic drug, is one of the first-line drugs used in the treatment of SCLC. Studies have shown that the objective rate of effectiveness of nedaplatin in combination with etoposide in the treatment of SCLC was 49.3% [17]. Despite these relatively high success rates, the risks associated with chemotherapy cannot be ignored. Etoposide has been shown to induce pulmonary toxicity, and IPF-SCLC is identified as a contraindication for the drug, as per the Japanese package insert [18]. Chemotherapy is likely to induce an acute exacerbation of IPF; therefore, risk–benefit analysis is very important whenever it is considered for patient management. However, currently, there are no other superior treatment options available. The performance status of both our patients was 2; therefore, we planned to initiate chemotherapy with nedaplatin and etoposide, while continuing the antifibrotic agents. Fortunately, the treatment plan resulted in improvement of the patients’ symptoms as well as reduction of the size of tumor shadow and lymph node enlargement evident on HRCT, without any change in the severity of fibrosis. However, despite the treatment success, residual shadows were still present in both patients. This suggested that the course of treatment may not have been adequate. Furthermore, there is also the possibility of other types of lung cancer co-existing, and bronchoscopy may be repeated if necessary.

In conclusion, individualized treatment is necessary for the management of patients with IPF and LC. However, it is necessary to ensure the safety of treatment. Chemotherapy can be considered in patients with poor lung function due to the presence of both IPF and SCLC; however, antifibrotic agents cannot be discontinued during the treatment [19]. Our findings highlight the need for studies on the development of new therapeutic agents that would enable the successful management of both SCLC and IPF.

Availability of data and material

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IPF:

-

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- ILD:

-

Interstitial lung disease

- LC:

-

Lung cancer

- SCLC:

-

Small cell lung cancer

- DLCO:

-

Diffusing capacity of the lungs for carbon monoxide

- HRCT:

-

High-resolution computed tomography

- CTCAE v5.0:

-

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events v5.0

- ECOG:

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group

References

Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):788–824.

Le Jeune I, Gribbin J, West J, Smith C, Cullinan P, Hubbard R. The incidence of cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and sarcoidosis in the UK. Respir Med. 2007;101(12):2534–40.

Kudoh S, Kato H, Nishiwaki Y, et al. Interstitial lung disease in Japanese patients with lung cancer: a cohort and nested case-control study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(12):1348–57.

Turner-Warwick M, Lebowitz M, Burrows B, Johnson A. Cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis and lung cancer. Thorax. 1980;35(7):496–9.

JafariNezhad A, YektaKooshali MH. Lung cancer in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(8):e0202360.

Antoniou KM, Tomassetti S, Tsitoura E, Vancheri C. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and lung cancer: a clinical and pathogenesis update. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2015;21(6):626–33.

Karampitsakos T, Tzilas V, Tringidou R, et al. Lung cancer in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45:1–10.

Vancheri C. Common pathways in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cancer. Eur Respir Rev. 2013;22(129):265–72.

Xu Y, Zhong W, Zhang L, Zhao J, Li L, Wang M. Clinical characteristics of patients with lung cancer and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis in China. Thorac Cancer. 2012;3(2):156–61.

Isobe K, Hata Y, Sakamoto S, Takai Y, Shibuya K, Homma S. Clinical characteristics of acute respiratory deterioration in pulmonary fibrosis associated with lung cancer following anti-cancer therapy. Respirology. 2010;15(1):88–92.

Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, et al. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176(7):636–43.

Fukunaga K, Yokoe S, Kawashima S, Uchida Y, Nakagawa H, Nakano Y. Nintedanib prevented fibrosis progression and lung cancer growth in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Respirol Case Rep. 2018;6(8):e00363.

Miyazaki K, Satoh H, Kurishima K, et al. Interstitial lung disease in patients with small cell lung cancer. Med Oncol. 2010;27(3):763–7.

Togashi Y, Masago K, Handa T, et al. Prognostic significance of preexisting interstitial lung disease in Japanese patients with small-cell lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer. 2012;13(4):304–11.

Demedts IK, Vermaelen KY, van Meerbeeck JP. Treatment of extensive-stage small cell lung carcinoma: current status and future prospects. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(1):202–15.

Berger C, Xia F, Maurer MH, Schwab S. Neuroprotection by pravastatin in acute ischemic stroke in rats. Brain Res Rev. 2008;58(1):48–56.

Fuentes B, Martinez-Sanchez P, Diez-Tejedor E. Lipid-lowering drugs in ischemic stroke prevention and their influence on acute stroke outcome. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;27(Suppl 1):126–33.

Suzuki H, Hirashima T, Kobayashi M, et al. Effect of topotecan as second-line chemotherapy for small cell lung cancer patients with interstitial lung disease. J Chemother. 2011;23(6):367–70.

Tzouvelekis A, Spagnolo P, Bonella F, et al. Patients with IPF and lung cancer: diagnosis and management. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(2):86–8.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to all the individuals who participated in the preparation of this case report.

Funding

This case was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China of the Second Hospital branch Center of Jilin University (Grant no. KA001030001) and National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 81672297). The Funding bodies had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XYZ designed the study, collected the clinical data and wrote the manuscript; WL drafted the manuscript and provided image data. CYL participated in collecting the data and drafting the manuscript. ZZS helped draft the manuscript and edited the pictures. JZ proof read the manuscript and revised the final version of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

We have obtained written consent from both the patients for publication of their case reports with accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, X., Li, W., Li, C. et al. Chemotherapy in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and small-cell lung cancer with poor lung function. BMC Pulm Med 21, 122 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01489-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01489-4