Abstract

Background

Intravesical instillation of bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) as a treatment for superficial bladder cancer rarely causes pulmonary complications. While published cases have been pathologically characterized by multiple granulomatous lesions due to disseminated infection, no case presenting as a solitary pulmonary nodule has been reported.

Case presentation

A man in his 70 s was treated with intravesical BCG for early-stage bladder cancer. After 1 year, he complained of productive cough with a solitary pulmonary nodule at the left lower lobe of his lung being detected upon chest radiography. His sputum culture result came back positive, with conventional polymerase chain reaction (PCR) identifying Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. However, tuberculosis antigen-specific interferon-gamma release assay came back negative. Considering a history of intravesical BCG treatment, multiplex PCR was conducted, revealing the strain to be Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG. The patient was then treated with isoniazid, ethambutol, levofloxacin, and para-aminosalicylic acid following an antibiotic susceptibility test showing pyrazinamide resistance, after which the size of nodule gradually decreased.

Conclusion

This case highlights the rare albeit potential radiographic presentation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG, showing a solitary pulmonary nodule but not multiple granulomatous lesions, after intravesical BCG treatment. Differentiating Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG from Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. tuberculosis is crucial to determine whether intravesical BCG treatment could be continued for patients with bladder cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) is synthesized from a weakened strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG originally developed for a tuberculosis (TB) vaccine in 1908 [1]. In 1976, Morales and coauthors published the first successful use of intravesical BCG for patients with bladder cancer [2], which has currently become the main intravesical immunotherapy for early-stage bladder cancer [3, 4]. Although BCG treatment is generally well tolerated due to its low virulence in immunocompetent patients, local and systemic complications may be observed in rare cases [5]. Indeed, studies have shown that severe adverse effects may occur in less than 5% of patients who received intravesical BCG treatment, with most of the symptoms resulting from disseminated BCG infection [6,7,8,9].

Among the severe adverse effects, lung involvement had been observed in 0.3–0.7% of patients [10,11,12]. While multiple granulomatous lesions due to miliary infection or interstitial lung diseases caused by hyperimmune responses have been previously documented as radiological features [3, 10], no other radiological patterns have been reported. We herein present the first case diagnosed with Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG infection who presented with a solitary pulmonary nodule after intravesical BCG treatment for superficial bladder cancer.

Case presentation

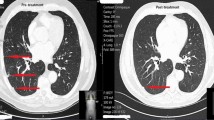

A man in his 70 s with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease had undergone transurethral resection for early-stage bladder cancer, after which he received monthly intravesical BCG of 80 mg treatments for 8 times [13]. After 1 year, he started to complain of productive cough, with physical examination revealing a body temperature of 36.8 °C, an SpO2 of 96%, a blood pressure of 126/63 mmHg, and a heart rate of 103 beats/min. Laboratory tests revealed a normal leukocyte count (7400 cells/μL) and slightly elevated serum levels of C-reactive protein (0.03 mg/dL), while chest X-ray detected a solitary pulmonary nodule in left middle lung field. Chest computed tomography showed a solitary nodule with a cavitary lesion in left lower lobe of the lung (segment 6) as shown in Fig. 1a and b. A tree-in-bud appearance characterized by a centrilobular branching structure was also found near the nodule.

Chest X-ray and computed tomography (CT). a Chest X-ray on admission showing a solitary nodule in the left middle lung field. b Chest CT on admission showing a 12-mm nodule with a cavitary lesion and a centrilobular branching structure (tree-in-bud appearance) in the lower lobe (S6) of the left lung. c Chest X-ray 9 months after treatment initiation showing decreased size of the solitary nodule in the left middle lung field. d Chest CT 9 months after treatment initiation showing a XX-mm nodule diminishing the tree-in-bud appearance

Although his sputum acid-fast bacilli smear came back negative, liquid culture (Mycobacteria Growth Indicator Tube, Becton Dickinson, Sparks, MD) revealed a positive result, with conventional PCR identifying Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Thereafter, he started receiving multiple anti-TB drugs, including isoniazid, rifampicin, ethambutol, and pyrazinamide as treatment for Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. tuberculosis infection. Two weeks later, rifampicin was replaced by levofloxacin due to fever and fatigue suspected to have been adverse effects of rifampicin.

Interestingly, we had a negative result for the TB-specific interferon-gamma release assay performed as an auxiliary diagnosis for active Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Considering a history of intravesical BCG treatment for bladder cancer, multiplex PCR was conducted, subsequently revealing the strain to be Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG [14]. Urinary acid-fast bacilli culture was confirmed to be negative. Given that routine antibiotic susceptibility test, the Kyokuto PZA test commercially available in Japan showed pyrazinamide resistance [15], the patient was started on ethionamide instead of pyrazinamide. Six weeks later, we observed liver injury, which was suspected to be induced by ethionamide because other potential causes including viral and alcoholic influence were excluded. Liver images using ultrasound and CT did not found abnormality, and we did not conduct liver biopsy. Consequently, ethionamide was replaced by para-aminosalicylic acid and then liver enzymes returned to normal range. Nine months after the treatment initiation, the size of the nodule significantly decreased, diminishing the surrounding tree-in-bud appearance, as shown in Fig. 1c and d. The treatment was planned to continue up to 12 months according to some previous reports [8], despite no official treatment guideline for Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG.

Discussion and conclusion

We herein present a case of Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG infection showing a solitary pulmonary nodule after intravesical BCG treatments for superficial bladder cancer. Pulmonary complications due to intravesical BCG treatment are quite rare. We searched cases of Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG infection using the search strategy (bladder cancer) AND [(BCG) OR (mycobacterium bovis)] AND [(lung) OR (pulmonary)] through the PubMed database assessed October 29, 2020 and summarized its clinical characteristics in Table 1 [9, 16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. Accordingly, most of the cases had multiple granulomatous lesions referred to as disseminated infection, with no report presenting a solitary pulmonary nodule.

Our case presented with a solitary pulmonary nodule without any other involvement. Although a tree-in-bud appearance, perhaps due to the inhalation of bacteria, was observed near the nodule, the patient had no history of being near cows carrying Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG or BCG powder inhalation. Thus, the tree-in-bud appearance may probably be attributed to the spread of bacteria from the nodule. Although Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG in the nodule can be suspected to have been transferred from the bladder through the bloodstream, it still remains uncertain why only a solitary nodule, instead of multiple granulomatous lesions, had formed. While an immunocompromised condition can be considered a risk factor for disseminated Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG infection [8], the patient in the current case had no underlying diseases apart from bladder cancer, which may perhaps have influenced the formation of the solitary nodule. However, even in immunocompetent hosts disseminated pattern has been observed. We are unable to provide clear reasons for the solitary formation in this case.

The purpose of distinguishing Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG from Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. tuberculosis in clinical practice warrants discussion. In Japan, TB-specific interferon-gamma release assay is allowed to test as an auxiliary diagnosis for active Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection by universal health insurance coverage. TB-specific interferon-gamma release assay results came back to negative in this case, which became a clue to suspect of Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG infection. However, because sensitivity of the test is reported approximately 80% [47], it should be noted that Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG cannot be suspected by the negative TB-specific interferon-gamma release assay results. While treatment regimens for Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG closely resemble those for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG is naturally resistant to pyrazinamide [48]. As far as drug susceptibility tests are concerned, discriminating between both strains in general practice may not always be required. Nevertheless, if Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG infection is diagnosed after intravesical BCG treatment, the aforementioned immunotherapy would no longer be appropriate. As such, even when a solitary pulmonary nodule is found among patients receiving intravesical BCG treatment for superficial bladder cancer, ruling out Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG infection is required.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available in this manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BCG:

-

Bacillus Calmette–Guérin

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

Abdallah AM, Behr MA. Evolution and strain variation in BCG. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1019:155–69.

Morales A, Eidinger D, Bruce AW. Intracavitary bacillus Calmette–Guérin in the treatment of superficial bladder tumors. J Urol. 1976;116(2):180–3.

Lamm DL. Efficacy and safety of bacille Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy in superficial bladder cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31(Suppl 3):S86-90.

Sarosdy MF, Lamm DL. Long-term results of intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin therapy for superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1989;142(3):719–22.

Rischmann P, Desgrandchamps F, Malavaud B, Chopin DK. BCG intravesical instillations: recommendations for side-effects management. Eur Urol. 2000;37(Suppl 1):33–6.

Lamm DL, van der Meijden PM, Morales A, Brosman SA, Catalona WJ, Herr HW, Soloway MS, Steg A, Debruyne FM. Incidence and treatment of complications of bacillus Calmette–Guérin intravesical therapy in superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1992;147(3):596–600.

Larsen ES, Nordholm AC, Lillebaek T, Holden IK, Johansen IS. The epidemiology of bacille Calmette–Guérin infections after bladder instillation from 2002 through 2017: a nationwide retrospective cohort study. BJU Int. 2019;124(6):910–6.

Pérez-Jacoiste Asín MA, Fernández-Ruiz M, López-Medrano F, Lumbreras C, Tejido A, San Juan R, Arrebola-Pajares A, Lizasoain M, Prieto S, Aguado JM. Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) infection following intravesical BCG administration as adjunctive therapy for bladder cancer: incidence, risk factors, and outcome in a single-institution series and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(17):236–54.

Steg A, Leleu C, Debré B, Boccon-Gibod L, Sicard D. Systemic bacillus Calmette–Guérin infection, “BCGitis”, in patients treated by intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin therapy for bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 1989;16(3):161–4.

Brausi M, Oddens J, Sylvester R, Bono A, van de Beek C, van Andel G, Gontero P, Turkeri L, Marreaud S, Collette S, et al. Side effects of Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) in the treatment of intermediate- and high-risk Ta, T1 papillary carcinoma of the bladder: results of the EORTC genito-urinary cancers group randomised phase 3 study comparing one-third dose with full dose and 1 year with 3 years of maintenance BCG. Eur Urol. 2014;65(1):69–76.

Caramori G, Artioli D, Ferrara G, Cazzuffi R, Pasquini C, Libanore M, Guardigni V, Guzzinati I, Contoli M, Rossi R, et al. Severe pneumonia after intravesical BCG instillation in a patient with invasive bladder cancer: case report and literature review. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2013;79(1):44–8.

Marques M, Vazquez D, Sousa S, Mesquita G, Duarte M, Ferreira R. Disseminated Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) infection with pulmonary and renal involvement: a rare complication of BCG immunotherapy. A case report and narrative review. Pulmonology 2020, 26(6):346–52.

Flaig TW, Spiess PE, Agarwal N, Bangs R, Boorjian SA, Buyyounouski MK, Chang S, Downs TM, Efstathiou JA, Friedlander T, et al. Bladder cancer, version 3.2020, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2020;18(3):329–54.

Pinsky BA, Banaei N. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for rapid identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex members to the species level. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46(7):2241–6.

Aono A, Hirano K, Hamasaki S, Abe C. Evaluation of BACTEC MGIT 960 PZA medium for susceptibility testing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis to pyrazinamide (PZA): compared with the results of pyrazinamidase assay and Kyokuto PZA test. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002;44(4):347–52.

Barankiewitz I, Manor H, Strauss S. Miliary lung disease induced by intravesical Bacillus Calmette–Guérin treatment. Eur Radiol. 1999;9(9):1933.

Böhle A, Kirsten D, Schröder KH, Knipper A, Fornara P, Magnussen H, Jocham D. Clinical evidence of systemic persistence of bacillus Calmette–Guérin: long-term pulmonary bacillus Calmette–Guérin infection after intravesical therapy for bladder cancer and subsequent cystectomy. J Urol. 1992;148(6):1894–7.

Calleris G, Marra G, Corcione S, Oderda M, Cardellino C, Audagnotto S, Frea B, De Rosa FG, Gontero P. Miliary pulmonary infection after BCG intravesical instillation: a rare, misdiagnosed and mistreated complication. Infez Med. 2017;25(4):366–70.

Chang H, Klein JS, Norotsky M, Cooper K. Granulomatous chest disease following intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy. J Thorac Imaging. 2004;19(1):60–2.

Cho JL, McDermott S, Tsibris AM, Mark EJ: CASE RECORDS of the MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL. Case 37–2015. A 76-Year-Old Man with Fevers, Leukopenia, and Pulmonary Infiltrates. N Engl J Med. 2015, 373(22):2162–72.

Clérigo V, Castro A, Mourato T, Gomes C. A rare case of granulomatous pneumonitis due to intravesical BCG for bladder cancer. Acta Med Port. 2019;32(4):316–20.

Dammert P, Boujaoude Z, Rafferty W, Kass J. Fever of unknown origin and pancytopenia caused by culture-proven delayed onset disseminated bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) infection after intravesical instillation. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;1:2013.

De Diego A, Rogado MC, Prieto M, Nauffal D, Perpiñá M. Disseminated pulmonary granulomas after intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy. Respiration. 1997;64(4):304–6.

Delimpoura V, Samitas K, Vamvakaris I, Zervas E, Gaga M. Concurrent granulomatous hepatitis, pneumonitis and sepsis as a complication of intravesical BCG immunotherapy. BMJ Case Rep. 2013; 1:2013.

Elkabani M, Greene JN, Vincent AL, VanHook S, Sandin RL. Disseminated Mycobacterium bovis after intravesicular bacillus calmette-Gu rin treatments for bladder cancer. Cancer Control. 2000;7(5):476–81.

Gupta RC, Lavengood R Jr, Smith JP. Miliary tuberculosis due to intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin therapy. Chest. 1988;94(6):1296–8.

Iantorno R, Nicolai M, Storto ML, Ciccotosto C, Cipollone G, Mastroprimiano G, Tenaglia RL. Miliary tuberculosis of the lung in a patient treated with bacillus Calmette–Guérin for superficial bladder cancer. J Urol. 1998;159(5):1639–40.

Jasmer RM, McCowin MJ, Webb WR. Miliary lung disease after intravesical bacillus Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy. Radiology. 1996;201(1):43–4.

Kesten S, Title L, Mullen B, Grossman R. Pulmonary disease following intravesical BCG treatment. Thorax. 1990;45(9):709–10.

Kirsten D, Rieger U, Schröder KH, Böhle A, Magnussen H. Pulmonary tuberculosis due to bacille Calmette–Guérin. Clin Investig. 1993;71(10):787–90.

Kristjansson M, Green P, Manning HL, Slutsky AM, Brecher SM, von Reyn CF, Arbeit RD, Maslow JN. Molecular confirmation of bacillus Calmette–Guérin as the cause of pulmonary infection following urinary tract instillation. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17(2):228–30.

LeMense GP, Strange C: Granulomatous pneumonitis following intravesical BCG. What therapy is needed? Chest. 1994, 106(5):1624–6.

Manfredi R, Dentale N, Piergentili B, Pultrone C, Brunocilla E. Tubercular disease caused by Bacillus of Calmette–Guérin as a local adjuvant treatment of relapsing bladder carcinoma. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2009;24(5):621–7.

McParland C, Cotton DJ, Gowda KS, Hoeppner VH, Martin WT, Weckworth PF. Miliary Mycobacterium bovis induced by intravesical bacille Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(5 Pt 1):1330–3.

Mehta AR, Mehta PR, Mehta RL: A cough conundrum in a patient with a previous history of BCG immunotherapy for bladder cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:1.

Naudžiūnas A, Juškaitė R, Žiaugrytė I, Unikauskas A, Varanauskienė E, Mašanauskienė E. Tuberculosis complications after BCG treatment for urinary bladder cancer. Medicina (Kaunas). 2012;48(11):563–5.

Nazir T, Talab SK, Kadir S. Systemic granulomatous disease and syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone. Br J Hosp Med (Lond). 2010;71(8):472–3.

Palayew M, Briedis D, Libman M, Michel RP, Levy RD. Disseminated infection after intravesical BCG immunotherapy. Detection of organisms in pulmonary tissue. Chest. 1993, 104(1):307–9.

Rabe J, Neff KW, Lehmann KJ, Mechtersheimer U, Georgi M. Miliary tuberculosis after intravesical bacille Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy for carcinoma of the bladder. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172(3):748–50.

Reinert KU, Sybrecht GW. T helper cell alveolitis after bacillus Calmette–Guérin immunotherapy for superficial bladder tumor. J Urol. 1994;151(6):1634–7.

Rosati Y, Fabiani A, Taccari T, Ranaldi R, Mammana G, Tubaldi A. Intravesical BCG therapy as cause of miliary pulmonary tuberculosis. Urologia. 2016;83(1):49–53.

Shimizu G, Amano R, Nakamura I, Wada A, Kitagawa M, Toru S. Disseminated Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (BCG) infection and acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonitis: an autopsy case report and literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2020;20(1):708.

Smith DM: BCG-osis following intravesical BCG treatment leading to miliary pulmonary nodules, penile granulomas and a mycotic aortic aneurysm. BMJ Case Rep 2016;2016:1.

Smith RL, Alexander RF, Aranda CP. Pulmonary granulomata. A complication of intravesical administration of bacillus Calmette–Guérin for superficial bladder carcinoma. Cancer 1993;71(5):1846–7.

Thupili CR, Chamarthi SK, Ghosh S. Bacillus Calmette–Guérin (osis). J Urol. 2014;191(6):1876–7.

Venn RM, Sharma N. Resolution without treatment of granulomatous pneumonitis due to intravesical BCG for bladder cancer. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:1.

Whitworth HS, Badhan A, Boakye AA, Takwoingi Y, Rees-Roberts M, Partlett C, Lambie H, Innes J, Cooke G, Lipman M, et al. Clinical utility of existing and second-generation interferon-γ release assays for diagnostic evaluation of tuberculosis: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(2):193–202.

Esteban J, Muñoz-Egea MC. Mycobacterium Bovis and other uncommon members of the mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. Microbiol Spectr. 2016, 4(6):1.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Ai Tanaka for clinical advice and the members of the Research Institute of Tuberculosis, Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association for the identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MI, ST and YT1 contributed to the data collection. YT2, YI and SM conducted multiplex PCR. MI, MY, ST, KK, YT1, KH, SM, and JK drafted the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable due to a case report not including personally identifiable information.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent to publish this report was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

All authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Itai, M., Yamasue, M., Takikawa, S. et al. A solitary pulmonary nodule caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis var. BCG after intravesical BCG treatment: a case report. BMC Pulm Med 21, 115 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01475-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-021-01475-w