Abstract

Background

The lectin-like domain of TNF-α can be mimicked by synthetic TIP peptides and represents an innovative pharmacologic option to treat edematous respiratory failure. TIP inhalation was shown to reduce pulmonary edema and improve gas exchange. In addition to its edema resolution effect, TIP peptides may exert some anti-inflammatory properties. The present study therefore investigates the influence of the inhaled TIP peptide AP318 on intrapulmonary inflammatory response in a porcine model of systemic sepsis.

Methods

In a randomized-blinded setting lung injury was induced in 18 pigs by lipopolysaccharide-infusion and a second hit with a short period of ventilator-induced lung stress, followed by a six-hour observation period. The animals received either two inhalations with the peptide (AP318, 2×1 mg kg−1) or vehicle. Post-mortem pulmonary expression of inflammatory and mechanotransduction markers were determined by real-time polymerase chain reaction (IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, COX-2, iNOS, amphiregulin, and tenascin-c). Furthermore, regional histopathological lung injury, edema formation and systemic inflammation were quantified.

Results

Despite similar systemic response to lipopolysaccharide infusion in both groups, pulmonary inflammation (IL-6, TNF-α, COX-2, tenascin-c) was significantly mitigated by AP318. Furthermore, a Western blot analysis shows a significantly lower of COX-2 protein level. The present sepsis model caused minor lung edema formation and moderate gas exchange impairment. Six hours after onset pathologic scoring showed no improvement, while gas exchange parameters and pulmonary edema formation were similar in the two groups.

Conclusion

In summary, AP318 significantly attenuated intrapulmonary inflammatory response even without the presence or resolution of severe pulmonary edema in a porcine model of systemic sepsis-associated lung injury. These findings suggest an anti-inflammatory mechanism of the lectin-like domain beyond mere edema reabsorption in endotoxemic lung injury in vivo.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sepsis is a frequent cause of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Sepsis-induced ARDS can be caused by a primary pulmonary focus or a systemic transmission, while isolated ARDS may also trigger a systemic response leading to multiple organ failure [1,2]. A key mediator of early pulmonary inflammation is tumor-necrosis-factor-alpha (TNF-α), which is known to exert pleiotropic effects [3,4]. The lectin-like domain of TNF-α, which is located at the tip of the pyramidal molecule, elicits edema resolution and endothelial barrier sealing effects independently from the pro-inflammatory main effects of the cytokine. The lectin-like domain therefore contributes to the dichotomal role of TNF-α in severe inflammatory conditions [4]. This domain can be mimicked by synthetic TIP peptides, which recently emerged as a novel approach for treatment of ARDS and are currently tested for clinical application [4-6]. Via activation of epithelial sodium channels (ENaC) in type II alveolar cells TIP peptides help to create an osmotic gradient leading to resolution of alveolar edema [7-9]. Edema formation through microvascular hyperpermeability can also be limited by the TIP peptide [8,10]. Furthermore, inhalative application was shown to limit inflammatory response in terms of leucocyte infiltration and reactive oxygen species generation [11]. In a recent porcine model of bronchoalveolar lavage induced ARDS inhalation of the TIP peptide AP301 (APEPTICO, Vienna, Austria) was effective in improving the overall pulmonary function, which was associated with edema reduction [12]. These findings have not been confirmed in vivo under conditions of systemic sepsis or severe inflammatory response. Based on previous in vitro data the synthetic peptide AP318 may represent a more potent variant of the initially synthesized TIP peptide [13,14], but only showed comparable effects to the first TIP peptide AP301 in a porcine model in vivo [15]. To further characterize the effects of the lectin-like domain on intrapulmonary inflammation, a porcine model of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced sepsis with an additional ventilator-induced lung injury (VILI) component was examined. Our primary hypothesis was that repetitive AP318 inhalation would lead to an attenuation of intrapulmonary inflammatory response, and secondary improve gas exchange and overall lung injury.

Methods

This study was approved by the state and institutional animal care committee (Landesuntersuchungsamt Rheinland-Pfalz, Koblenz, Germany; approval number 23 177-07/G12-1-058), and conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz, Germany. 18 juvenile pigs (weight 25–27 kg) were examined in a randomized, investigator-blinded setting.

Anesthesia and instrumentation

After sedation with intramuscular injection of ketamine (8 mg kg−1) and midazolam (0.2 mg kg−1) and vascular access by ear vein puncture, anesthesia was induced and maintained by intravenous propofol and fentanyl administration (8–12 mg kg−1 h−1 / 0.1-0.2 mg h−1). A single dose of atracurium (0.5 mg kg−1) was applied to facilitate orotracheal intubation. Ventilation (Respirator: AVEA®, CareFusion, USA) was started in pressure-controlled mode with a tidal volume of (Vt) of 8 mL kg−1, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5 cmH2O, fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) of 0.4 and a variable respiratory rate to maintain normocapnia. A balanced saline solution (Sterofundin iso, B. Braun, Germany) was continuously infused at a rate of 10 mL kg−1 h−1. Vascular catheters were placed ultrasound-guided in Seldinger’s technique and under sterile conditions: an arterial line, a pulse contour cardiac output catheter (PiCCO, Pulsion Medical Systems, Germany) and central venous line were inserted via femoral access. An introducer for a pulmonary artery catheter was placed via the right internal jugular vein. Ventilatory and extended hemodynamic parameters were recorded continuously (Datex S/5, GE Healthcare, Germany). Body temperature was measured by a rectal probe and normothermia was maintained by body surface warming.

Experimental protocol

Following instrumentation baseline parameters were assessed at healthy state. Figure 1 summarizes the experimental protocol: systemic inflammation was induced by continuous LPS infusion (Escherichia coli serotype O111:B4, Sigma-Aldrich, Switzerland) for one hour at 100 μg kg−1 h−1, followed by 10 μg kg−1 h−1 for the entire experiment. Initial high-dose infusion was combined with a non-protective ventilation setting (Vt 25 mL kg−1, zero PEEP, FiO2 1.0) to add a VILI component. Afterwards the ventilation mode was switched to a more lung protective setting: Vt of 8 mL kg−1, PEEP 5 cmH2O, FiO2 of 0.4, and a variable respiratory rate to maintain a pH > 7.2. The animals were monitored over six hours after sepsis induction. During the induction phase a non-participant randomized the animals into two groups and prepared the peptide solution for blinded endotracheal inhalation:

-

(1)

AP318 group (1 mg kg−1 AP318 at zero and three hours, n = 9)

-

(2)

Control group (CTRL; vehicle solution at zero and three hours, n = 9)

The cognate TIP variant AP318 was provided by APEPTICO (Vienna, Austria) and delivered as lyophilisate at – 20°C. For preparation and conduction of the inhalation by means of a clinical nebulizer (Aeroneb ProX, Aerogen Ltd, Ireland) a previously established, standardized protocol was applied [15]. To maintain hemodynamic stability (mean arterial pressure > 60 mmHg) additional fluid boli were administered (150 ml of balanced saline or hydroxyethyl starch once every hour). Persisting instability was treated by continuous central venous noradrenaline infusion. At the end of the experiments the animals were killed in deep general anesthesia by intravenous injection of propofol (200 mg) and potassium chloride (40 mval).

Gene expression analysis and immunoblotting

To determine intrapulmonary inflammation mRNA levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1β (IL-1β), interleukin-6 (IL-6), TNF-α, and enzymes prostaglandin G/H synthase-2 (COX-2) and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) were quantified. Amphiregulin and tenascin-c expression levels were examined as surrogates of mechanical stress and remodeling. Additionally, ENaC expression was analyzed by quantification of the channel’s β-subunit. Four representative samples from the left lung (upper/lower lobe, each dependent/non-dependent) were collected, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C. RNA extraction and quantification procedure by real-time polymerase chain reaction (Lightcycler 480 PCR System, Roche Applied Science, Germany) was conducted as previously described in detail [16-18]. mRNA expression data were normalized against peptidylprolyl isomerase A (PPIA) as control gene. The applied primer sequences are summarized in Table 1. To determine tissue protein content of COX-2, the homogenates were analyzed by Western blotting following standard protocols [19]. Lung tissue samples (~100 mg) were homogenized in 4 ml solubilization buffer [100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.4, 20% sucrose, 0.5% SDS, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail (P2714 from Sigma-Aldrich, USA)] at 4°C using an Ultra-Turrax dispersing device (IKA, Germany). Protein content in the obtained homogenates was determined by bicinchoninic acid protein assay (Pierce, USA). The employed polyclonal, rabbit anti-cyclooxygenase-2 antibody (1:200; ab15191 from Abcam, UK) detected a single, predominant band of ~70 kDa in these porcine samples. COX-2 signal intensity was normalized for Ponceau S staining intensity of the applied total protein between ~25 kDa and ~170 kDa. Densitometric quantification was achieved using the commercial image analysis software AIDA (Raytest, Germany).

Hematological parameters

Blood gas values were obtained using a Rapidlab 248 device (Bayer Healthcare, Germany). Hematological parameters were determined during baseline, at the end of sepsis/VILI induction, and after three and six hours. Lactate plasma levels, leucocyte and platelet counts were analyzed by the Institute of Laboratory Medicine, Medical Center of the Johannes Gutenberg-University. The plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-α were determined by quantifying enzyme linked immunosorbent assays (Porcine IL-6 Quantikine ELISA, Porcine TNF-a Quantikine ELISA, R&D Systems, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Histopathological and lung water content assessment

The lungs were removed en-bloc after thoracotomy and a macroscopic lung injury score [15] was applied: four ventral and dorsal segments (each upper/lower right, upper/lower left) of the lung surface were examined for hemorrhage and congestion (2 points > 50%, 1 point for < 50%, 0 points for no or minimal changes). The left lung was weighted immediately after removal and dried afterwards at 60°C for 72 hours to determine the dry weight and wet to dry ratio. From the right lung samples of the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were taken and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen to determine the alveolar protein content and cytokine levels by ELISA. The right lung was then fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Representative tissue samples were paraffin embedded and cut for hematoxylin-eosin staining. A blinded investigator under supervision of a senior pathologist performed the histopathological assessment. In different lung regions (non-dependent periphery and bronchial, dependent periphery and bronchial) morphological changes were rated for seven criteria (alveolar edema, interstitial edema, hemorrhage, inflammatory infiltration, epithelial damage, microatelectasis and overdistension). The severity of each parameter ranged from 0 (no occurrence) to 5 points (complete field). For every lung region we used the mean value of four non-overlapping fields of view. The sum of the regional scores in all lung regions adds to a maximum injury score of 140 points (7 parameters × 5 maximum points per parameter from 4 lung regions). Additionally, we assessed the regional distribution of each parameter by comparison of the dependent versus non-dependent lung regions. Similar scoring procedures were described previously [20,21].

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or box-plots. For intergroup comparisons of the primary parameters (pulmonary mRNA expression, Figures 2 and 3) the Mann–Whitney-U-Test was used. Intragroup time courses of repetitively measured parameters were analyzed by Friedman ANOVA on ranks and post-hoc SNK-Test. Differences of secondary parameters (Figures 4, 5 and 6) between the two groups were assessed by the Mann–Whitney-U-Test. If multiple testing was performed, P values were adjusted by the Bonferroni method. P values below 0.05 were regarded as significant. Comparisons of physiological data for each time point (Table 1) were analyzed in an explorative manner by one-way ANOVA. The statistical software SigmaPlot 12.5 (Systat Inc., USA) was used.

Systemic hematological parameters and inflammatory cytokines. Time courses of systemic TNF-α, IL-6, lactate, leucocytes, and platelets. *Indicates P < 0.05 vs. baseline value, # P < 0.05 vs. Sepsis/VILI and × P < 0.05 vs. 3 h value. No significant intergroup differences. Sepsis/VILI values of TNF-α exceed the detection capacities of the available assays.

Results

Pulmonary and systemic inflammatory markers

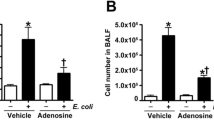

Intrapulmonary mRNA quantification yielded significantly lower overall expression of COX-2, TNF-α and IL-6 following AP318 inhalation, while the differences in IL-1β and iNOS expressions failed to reach significance (Figures 2 and 3). Additionally, a Western blot shows a significantly decreased COX-2 protein level in the lung tissue (Figure 3). ENaC expression was comparable in both groups (AP318 17.5 ± 9.2, CTRL 13.6 ± 7.4 [mRNA copies]; P = 0.12). Furthermore a decreased tenascin-c expression was detected after AP318 inhalation. No relevant locoregional variations were present. IL-6 and TNF-α levels from the bronchoalveolar lavage fluid were not different. Secondary, the systemic inflammatory response did not differ between the two groups. LPS infusion led to a sustained and persisting leucopenia. This was accompanied by decreases in platelet count and rising lactate levels. Plasma levels of IL-6 and TNF-α increased significantly in both groups with a peak within three hours (Figure 4).

Physiological data

Table 2 summarizes the time charts of hemodynamic and respiratory parameters. After sepsis/VILI induction the quotient of arterial partial pressure of oxygen and FiO2 (PaO2/FiO2) did not decrease. Afterwards PaO2/FiO2 and dynamic lung compliance (Cdyn) significantly decreased within three hours in both groups and persisted without recovery (Figure 5). The two groups showed no significant differences. Hemodynamic parameters were stable during baseline and sepsis/VILI induction, while over six hours continuous noradrenaline infusion was required in similar dosages (Table 1; AP318 8/9 animals, CTRL 7/9 animals). Hydroxyethyl starch was applied in all animals in comparable dosages.

Pathologic parameters

Post-mortem macroscopic and histologic evaluations yielded the presence of a sustained lung injury in both groups. The AP318 group shows lower scoring values, but fails to reach significance (Figure 6). The alveolar protein content was minimal in both groups. The most pronounced features of the histopathological scoring were inflammatory infiltration, overdistension, and atelectasis with edema formation playing a minor role. The CTRL group featured a higher grade of hemorrhage (Table 3). No relevant differences were detected regarding the ventral to dorsal distribution.

Discussion

The key results of the present porcine model of LPS/VILI-induced lung injury are: (1) AP318 significantly mitigates pulmonary mRNA expression of inflammatory mediators despite comparable systemic response to LPS exposition and (2) gas exchange or histopathological injury did not improve in the presence of low-grade pulmonary edema within six hours post insult.

Model characteristics

LPS is exposed as glycolipids of gram-negative bacteria in systemic bacteremia and can trigger inflammatory response to the point of septic shock and cardio-circulatory failure. Systemic effects of LPS in pigs include hemodynamic deterioration along with increased pulmonary arterial pressure and acute leucopenia [22], which is consistent with our findings. Intrapulmonary changes due to LPS infusion include accumulation of leucocytes and alveolar macrophages, as well as edema formation and endothelial injury [23]. In contrast to other models (i.e. bronchoalveolar lavage), no immediate atelectases and gas exchange impairment are generated [23]. In pigs LPS-induced lung changes measured by computer tomographic imaging and histopathologic scoring can develop over several hours without fulfillment of ARDS criteria [24]. Endotoxemic shock and therapy-refractory hemodynamic failure limit the maximum possible LPS infusion dosages in experimental models.

Regarding our primary hypothesis we designed this model to focus inflammatory response within the lung and not extensive edema formation or severe gas exchange impairment. The latter aspects were already assessed in our prior studies [12,15]. The present model causes a pulmonary lesion with a pronounced inflammatory response, which presents as significant worsening of PaO2/FiO2, respiratory mechanics, and post-mortem lung injury. Nevertheless, the complete pattern of ARDS according to the current criteria is not achieved despite addition of one-hour high Vt ventilation. This kind of short-term VILI does not induce sustained lung injury in healthy pigs [25]. However, synergistic effects of LPS infusion and VILI are used to achieve a full pattern human-like ARDS in experimental models [22].

Influence on inflammatory response

In response to LPS exposure TNF-α and IL-1β are released into the systemic circulation. In early ARDS alveolar macrophages are the main source of inflammatory cytokines that trigger inflammatory response by e.g. enhancing neutrophil accumulation [26,27]. We found high circulating plasma cytokine levels, which in comparison to their baselines values showed peaks immediately after sepsis/VILI induction (TNF-α) or three hours following induction (IL-6). Pathophysiological relevance is supported by data demonstrating that early and high circulating levels of IL-6 are associated with increased mortality [9]. Due to the strict local application of AP318 and ongoing LPS infusion a systemic effect appears unlikely, which is supported by our plasma cytokine levels. Interestingly, repetitive AP318 inhalation significantly attenuated pulmonary expression of several key inflammatory markers. Western blot analysis of the exemplarily chosen marker COX-2 demonstrated a significantly reduced content also on the protein level, indicating that the duration of the experiment (6 h) was sufficient to affect not only transcription, but also and in parallel direction translation. This observation authenticates the general use of real-time polymerase chain reaction to characterize the effects of AP318 on multiple markers in the described model.

The TIP peptide’s impact on lung inflammation was investigated previously in experimental ischemia and reperfusion–related lung injury, which demonstrated reduced neutrophil accumulation and reactive oxygen species generation, but failed to show differences in cytokine levels [11]. In contrast to the present study, the latter quantified cytokine levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, whereas we also determined inflammatory marker genes directly in lung tissue. Similar to these data, we found no differences in cytokine levels from the lavage fluid. Low level of edema formation in our study may have resulted in a limited effect (Figure 6, Table 3) on the alveolar cytokine levels. The level of expression is not dependent on the localization within the lung, which can be attributed to the systemic character of LPS infusion and the ventilation mode following the one-hour induction phase. Lung protective ventilation is known to avoid cyclical recruitment [28], whereas on-going VILI leads to regional differences in extend of inflammatory response [24]. The underlying molecular mechanisms of TIP have not been fully elucidated [11], and the present study was not design to clarify them. TIP directly activates ENaC by binding upon the channel’s α-subunit [29]. In the presence of LPS ENaC expression shows a biphasic curve with an upregulation within eight hours followed by a downregulation [30]. ENaC quantification yielded no significant differences between the two groups, which assumes that AP318 does not increase ENaC expression in the present model. Improvement of gas exchange and reduction of neutrophil invasion by TIP are linked, as both are inhibited by pharmacological ENaC blockade [11]. Our data, however, for the first time demonstrate an attenuation of pulmonary inflammatory response without significant edema reduction or improved gas exchange. Hence, edema absorption itself is hardly responsible for mitigation of inflammatory response despite being linked to ENaC. Furthermore, protein kinase C-α activation, which is induced upon Ca2+ influx by bacterial cytolysins like pneumolysin or listeriolysin, is inhibited by TIP [10,31]. This reduces permeability and reactive oxygen species release. Further studies, however, need to clarify, if mitigating of inflammatory response by a TIP peptide is a primary mechanism or occurs secondary to the mentioned mechanisms.

In order to differentiate between LPS and VILI-induced lung injury, we quantified markers for mechanical and inflammatory stress in amphiregulin and tenascin-c. Amphiregulin mRNA levels are induced exclusively following VILI, but not by LPS administration [25]. Tenascin-c, an extracellular matrix glycoprotein, is particularly involved in early inflammation and induced by inflammatory cytokines, lung remodeling, and fibroproliferation [32,33]. Tissue amphiregulin levels were not different between AP318 and CTRL group, indicating that mechanical stress was similar between both groups and that AP318 did not protect the lung from mechanical stress. Tenascin-c on the other hand was significantly lower in the AP318 group, suggesting that AP318 inhalation mitigates the activity associated with inflammation.

Influence on pulmonary function

In the present study gas exchange impairment and respiratory mechanics were not improved by AP318 inhalation. This is in contrast to previous data reporting a rapid [7,12,15] and lasting [11] amelioration of gas exchange or respiratory mechanics impairment after TIP peptide inhalation. The failure of compensatory mechanisms may contribute to the low efficacy of AP318 to improve gas exchange despite mitigation of inflammation: LPS significantly impairs pulmonary perfusion and inhibits hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction [34] and LPS-induced lung injury respond poorly to lung recruitment [35]. Recent data suggest that lung water content closely correlates with the ventilation/perfusion-distribution in non-septic experimental ARDS [36]. Pulmonary edema was not reduced by AP318, although the main effect of the TIP peptides is stimulation of ENaC and consequently edema resolution [9,14]. A porcine ARDS model of bronchoalveolar lavage and flooding as well as an ex vivo exo-/endotoxin rabbit model demonstrated that TIP inhalation rapidly resolved a preformed edema [8,12]. In contrast to these publications the present model was intentionally not accompanied with a relevant alveolar edema. Different model characteristics may therefore account for the lack of efficacy. Hence, the present data suggest that amelioration of gas exchange by the lectin-like domain appears to be linked rather to edema resolution and corresponding lung recruitment than to anti-inflammatory properties.

Implications and limitations of AP318 inhalation

Three key mechanisms need to be addressed to allow recovery from ARDS: resolution of the pulmonary edema, stabilization of the injured epithelial and endothelial structures and attenuation of the inflammatory response [1]. Therapeutic concepts primarily emphasize a strict adherence to lung protective ventilation and, if applicable, treatment of the underlying disease. Experimental data indicate that TIP peptide inhalation may target at least two of these pathomechanisms by stimulation of alveolar edema reabsorption and reversal of microvascular hyperpermeability [8,9,12]. The complex pattern of ARDS requires therapeutic strategies, which address multiple pathways. TIP peptides are therefore promising drugs to address endothelial barrier integrity, edema formation and inflammation simultaneously. Via inhalation the effects are locally restricted making systemic effects less likely [5,11]. Severe alveolar epithelial injury on the other hand may also limit beneficial pulmonary effects [37]. Hence, the lectin-like domain may be better suited for early states of edematous respiratory failure or ARDS rather than in severe or late fibroproliferative phases.

Conclusion

In a porcine model of systemic inflammatory response related lung injury with short-term VILI a repetitive inhalation of AP318 significantly attenuated the intrapulmonary expression of inflammatory marker genes. These findings provide new insights into the mechanisms of the TNF-α’s lectin-like domain beyond mere edema reduction and suggest for the first time an in vivo anti-inflammatory effect in endotoxemic lung injury.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Cdyn:

-

dynamic compliance

- COX-2:

-

prostaglandin G/H synthase-2

- CTRL:

-

control group

- ENaC:

-

epithelial sodium channels

- FiO2:

-

fraction of inspired oxygen

- IL-1β:

-

interleukin-1β

- IL-6:

-

interleukin-6

- iNOS:

-

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- LPS:

-

lipopolysaccharide

- PaO2:

-

arterial partial pressure of oxygen

- PEEP:

-

positive end-expiratory pressure

- PPIA:

-

peptidylprolyl isomerase A

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- TIP:

-

synthetic peptide mimicking the lectin-like domain of TNF-α

- TNF-α:

-

tumor-necrosis-factor-α

- VILI:

-

ventilator-induced lung injury

- Vt:

-

tidal volume

References

Matthay MA, Ware LB, Zimmerman GA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(8):2731–40.

Rubenfeld GD, Caldwell E, Peabody E, Weaver J, Martin DP, Neff M, et al. Incidence and outcomes of acute lung injury. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(16):1685–93.

Bhatia M, Moochhala S. Role of inflammatory mediators in the pathophysiology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Pathol. 2004;202(2):145–56.

Yang G, Hamacher J, Gorshkov B, White R, Sridhar S, Verin A, et al. The dual role of TNF in pulmonary edema. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2011;1(1):29–36.

Mascher D, Tscherwenka W, Mascher H, Fischer B. Sensitive determination of the peptide AP301–a motif of TNF-alpha–from human plasma using HPLC-MS/MS. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2012;908:18–22.

Schwameis R, Eder S, Pietschmann H, Fischer B, Mascher H, Tzotzos S, et al. A FIM study to assess safety and exposure of inhaled single doses of AP301-a specific ENaC channel activator for the treatment of acute lung injury. J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;54(3):341–50.

Elia N, Tapponnier M, Matthay MA, Hamacher J, Pache JC, Brundler MA, et al. Functional identification of the alveolar edema reabsorption activity of murine tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(9):1043–50.

Vadasz I, Schermuly RT, Ghofrani HA, Rummel S, Wehner S, Muhldorfer I, et al. The lectin-like domain of tumor necrosis factor-alpha improves alveolar fluid balance in injured isolated rabbit lungs. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(5):1543–50.

Tzotzos S, Fischer B, Fischer H, Pietschmann H, Lucas R, Dupre G, et al. AP301, a synthetic peptide mimicking the lectin-like domain of TNF, enhances amiloride-sensitive Na(+) current in primary dog, pig and rat alveolar type II cells. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2013;26(3):356–63.

Xiong C, Yang G, Kumar S, Aggarwal S, Leustik M, Snead C, et al. The lectin-like domain of TNF protects from listeriolysin-induced hyperpermeability in human pulmonary microvascular endothelial cells - a crucial role for protein kinase C-alpha inhibition. Vascul Pharmacol. 2010;52(5–6):207–13.

Hamacher J, Stammberger U, Roux J, Kumar S, Yang G, Xiong C, et al. The lectin-like domain of tumor necrosis factor improves lung function after rat lung transplantation–potential role for a reduction in reactive oxygen species generation. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(3):871–8.

Hartmann EK, Boehme S, Duenges B, Bentley A, Klein KU, Kwiecien R, et al. An inhaled tumor necrosis factor-alpha-derived TIP peptide improves the pulmonary function in experimental lung injury. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2013;57(3):334–41.

Hazemi P, Tzotzos SJ, Fischer B, Andavan GS, Fischer H, Pietschmann H, et al. Essential structural features of TNF-alpha lectin-like domain derived peptides for activation of amiloride-sensitive sodium current in A549 cells. J Med Chem. 2010;53(22):8021–9.

Shabbir W, Scherbaum-Hazemi P, Tzotzos S, Fischer B, Fischer H, Pietschmann H, et al. Mechanism of action of novel lung edema therapeutic AP301 by activation of the epithelial sodium channel. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;84(6):899–910.

Hartmann EK, Thomas R, Liu T, Stefaniak J, Ziebart A, Duenges B, et al. TIP peptide inhalation in experimental acute lung injury: effect of repetitive dosage and different synthetic variants. BMC Anesthesiology. 2014;14:42.

Luh C, Gierth K, Timaru-Kast R, Engelhard K, Werner C, Thal SC. Influence of a brief episode of anesthesia during the induction of experimental brain trauma on secondary brain damage and inflammation. PLoS One. 2011;6(5):e19948.

Spieth PM, Guldner A, Beda A, Carvalho N, Nowack T, Krause A, et al. Comparative effects of proportional assist and variable pressure support ventilation on lung function and damage in experimental lung injury. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(9):2654–61.

Timaru-Kast R, Luh C, Gotthardt P, Huang C, Schafer MK, Engelhard K, et al. Influence of age on brain edema formation, secondary brain damage and inflammatory response after brain trauma in mice. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e43829.

Fuhrmeister J, Tews M, Kromer A, Moosmann B. Prooxidative toxicity and selenoprotein suppression by cerivastatin in muscle cells. Toxicol Lett. 2012;215(3):219–27.

Spieth PM, Knels L, Kasper M, Domingues Quelhas A, Wiedemann B, Lupp A, et al. Effects of vaporized perfluorohexane and partial liquid ventilation on regional distribution of alveolar damage in experimental lung injury. Intensive Care Med. 2007;33(2):308–14.

Wang HM, Bodenstein M, Duenges B, Ganatti S, Boehme S, Ning Y, et al. Ventilator-associated lung injury superposed to oleic acid infusion or surfactant depletion: histopathological characteristics of two porcine models of acute lung injury. Eur Surg Res. 2010;45(3–4):121–33.

Matute-Bello G, Frevert CW, Martin TR. Animal models of acute lung injury. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;295(3):L379–99.

Wang HM, Bodenstein M, Markstaller K. Overview of the pathology of three widely used animal models of acute lung injury. Eur Surg Res. 2008;40(4):305–16.

Otto CM, Markstaller K, Kajikawa O, Karmrodt J, Syring RS, Pfeiffer B, et al. Spatial and temporal heterogeneity of ventilator-associated lung injury after surfactant depletion. J Appl Physiol. 2008;104(5):1485–94.

Dolinay T, Kaminski N, Felgendreher M, Kim HP, Reynolds P, Watkins SC, et al. Gene expression profiling of target genes in ventilator-induced lung injury. Physiol Genomics. 2006;26(1):68–75.

Mittal N, Sanyal SN. Cycloxygenase inhibition enhances the effects of surfactant therapy in endotoxin-induced rat model of ARDS. Inflammation. 2011;34(2):92–8.

Matthay MA, Zemans RL. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:147–63.

Hartmann EK, Boehme S, Bentley A, Duenges B, Klein KU, Elsaesser A, et al. Influence of respiratory rate and end-expiratory pressure variation on cyclic alveolar recruitment in an experimental lung injury model. Crit Care. 2012;16(1):R8.

Czikora I, Alli A, Bao HF, Kaftan D, Sridhar S, Apell HJ, et al. A novel tumor necrosis factor-mediated mechanism of direct epithelial sodium channel activation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(5):522–32.

Sheng SJ, Nie YC, Lin F, Li PB, Liu MH, Xie CS, et al. Biphasic modulation of alpha-ENaC expression by lipopolysaccharide in vitro and in vivo. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2014;10(2):773–7.

Lucas R, Czikora I, Sridhar S, Zemskov E, Gorshkov B, Siddaramappa U, et al. Mini-review: novel therapeutic strategies to blunt actions of pneumolysin in the lungs. Toxins. 2013;5(7):1244–60.

Chiquet-Ehrismann R, Chiquet M. Tenascins: regulation and putative functions during pathological stress. J Pathol. 2003;200(4):488–99.

Snyder JC, Zemke AC, Stripp BR. Reparative capacity of airway epithelium impacts deposition and remodeling of extracellular matrix. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2009;40(6):633–42.

Easley RB, Mulreany DG, Lancaster CT, Custer JW, Fernandez-Bustamante A, Colantuoni E, et al. Redistribution of pulmonary blood flow impacts thermodilution-based extravascular lung water measurements in a model of acute lung injury. Anesthesiology. 2009;111(5):1065–74.

Fernandez-Bustamante A, Easley RB, Fuld M, Mulreany D, Hoffman EA, Simon BA. Regional aeration and perfusion distribution in a sheep model of endotoxemic acute lung injury characterized by functional computed tomography imaging. Crit Care Med. 2009;37(8):2402–11.

Hartmann EK, Duenges B, Baumgardner JE, Markstaller K, David M. Correlation of thermodilution-derived extravascular lung water and ventilation/perfusion-compartments in a porcine model. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39(7):1313–7.

Hartmann EK, Bentley A, Duenges B, Klein KU, Boehme S, Markstaller K, et al. TIP peptide inhalation in oleic acid-induced experimental lung injury: a post-hoc comparison. BMC Research Notes. 2013;6(1):385.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Dagmar Dirvonskis und Dana Pieter for their excellent technical assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The study was funded in part by a Stage 1 grant of the Johannes Gutenberg-University Mainz to EKH. The authors further received a research grant by APEPTICO (Vienna, Austria), the patent holder of the peptide AP318. The funders had no influence on study design, data collection and analysis, manuscript preparation or decision to publish.

Authors’ contributions

EKH and MD coordinated and supervised the experiments. EKH, AZ, RT, TL and BD conducted the experiments. EKH, AZ, AS, MT, BM, JK and SCT performed the post-mortem assessment and data analysis. EKH drafted the manuscript. SCT and MD participated in the study design, supervision of laboratory and revision of the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hartmann, E.K., Ziebart, A., Thomas, R. et al. Inhalation therapy with the synthetic TIP-like peptide AP318 attenuates pulmonary inflammation in a porcine sepsis model. BMC Pulm Med 15, 7 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-015-0002-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-015-0002-6