Abstract

Background

Recognizing the established link between social determinants of health, such as social support, good governance, and perceived discrimination, and individual mental health, this study aims to delve deeper into the specific relationships within the Iranian adult population. It seeks to elucidate the potential mediating role of quality of life in the association between mental health disorders (MHDs) and these social factors.

Methods

This cross-sectional study employed path analysis to investigate the relationships between social determinants of health and MHDs among 725 Iranian adults in Tabriz, Northwest Iran. Data collection occurred between March and September 2022, utilizing a multi-stage and cluster sampling approach. Good governance, social support, perceived discrimination, MHDs, and quality of life were assessed using valid questionnaires. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS-24 and Lisrel-8 software, with a significance level set at p < 0.05.

Results

This study found that nearly 70.0% of the participants reported experiencing mental health problems. The path analysis showed that good governance had a significant indirect and negative effect on MHDs via quality of life (β = -0.05; P < 0.05). Major racial discrimination had a positive relationship in the direct and indirect paths (β = 0.24; P < 0.01). While, social support was a directly and indirectly significant predictor of decreased MHDs (β = -0.17, p < 0.01). Furthermore, quality of life had a negative relationship on the indirect path with MHDs (β = -0.24, P < 0.01).

Conclusions

This study reveals a significant burden of mental health issues among Iranian adults. It highlights the crucial role of social factors like good governance, social support, and perceived discrimination in shaping mental health through their impact on quality of life. Consequently, addressing these factors through improved governance, strengthened social support systems, and active efforts to reduce discrimination is essential for promoting mental well-being.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mental health has become a major public health issue in recent decades, reflecting society’s overall well-being. Global estimates from 2016 indicate that mental health disorders (MHDs) accounted for 13% of the global burden of disease in disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [1]. This figure rose to 16% in 2019, with an estimated economic cost of 5 trillion dollars [2]. Notably, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that depression and anxiety alone are prevalent in Iran at 3863.9 and 7268.1 cases per 100,000 people, respectively, with an age-standardized DALY of 2295.8 per 100,000 people [3]. Also, a systematic review estimated the prevalence of psychiatric disorders at 31.03% [4]. Beyond the significant economic burden, MHDs negatively impact quality of life (QoL) and can exacerbate other illnesses, increase disability rates, and ultimately elevate mortality risks [5].

While biological factors contribute to mental health, social and economic variables, known as the social determinants of health, also play a significant role. These determinants encompass the broader conditions in which individuals live, encompassing the circumstances of their birth, upbringing, work, and ultimately, death [6]. The prominent determinants such as good governance, perceived discrimination, and social support have been pointed out by previous studies. Effective governance emerges as a crucial factor influencing both individual and societal well-being [7]. Good governance fosters social capital, strengthens social support networks, expands employment opportunities, and ensures household security, directly impacting both mental and physical health [8]. In low- and middle-income countries, proficient management of mental health systems is particularly critical to addressing the high prevalence of mental disorders [9]. The government, together with its policies regarding health, the labor market, housing, employment, taxation, income distribution, and social welfare, plays a pivotal role in either exacerbating or ameliorating socio-economic disparities, perceived discrimination, and ultimately impacting health outcomes [10].

Perceived discrimination, encompassing unfair actions, judgments, or behaviors based on characteristics like age, gender, race, ethnicity, or religion, has a significant negative impact on individuals’ well-being [11]. The stress model posits that perceived discrimination triggers negative emotions, leading to psychological strain and impacting biological processes, ultimately influencing both mental and physical health [12, 13]. Additionally, research suggests that perceived discrimination disrupts sleep patterns [14]. Furthermore, conditions like heart disease, oral health issues, and detrimental behaviors such as smoking and alcohol consumption are negatively affected by perceived discrimination [11]. Existing literature extensively supports the correlation between perceived discrimination and adverse health outcomes, including mental health issues, among youth, elderly individuals, and immigrant populations [11, 15,16,17]. Social support, encompassing emotional, informational, and practical assistance from family, friends, and the community, plays a crucial role in promoting mental well-being and reducing the risk of illness, depression, and anxiety [13, 18, 19]. It influences health through both direct and protective mechanisms. The primary goal of healthcare systems worldwide is to enhance the well-being and the QoL of their populations. QoL, a relatively new concept gaining prominence in healthcare, focuses on individual well-being and societal responsibility [20, 21].

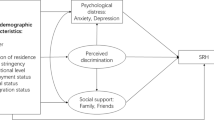

A scarcity of research exists on the association between perceptions of good governance and MHDs. Prior investigations examining the influence of social support, QoL, and perceived discrimination have largely concentrated on disadvantaged groups, such as immigrants and older adults. The current body of research regarding the interconnection between QoL and mental health is both inconclusive and methodologically flawed. Prior studies have established a reciprocal relationship between mental health and QoL, indicating that poor mental health can result in diminished QoL and vice versa [22]. The association between QoL and mental health is complex and may not be fully understood through basic correlations alone. The application of more intricate modeling techniques, such as mediation analysis, can aid in elucidating these intricate relationships. Therefore, this study aims to investigate the mediating role of QoL in the association between MHDs, good governance, perceived discrimination, and social support. Understanding these mediating factors can provide valuable insights for developing effective intervention strategies and improving mental health treatment pathways. The following hypotheses were tested in the current study (See Fig. 1):

H1: Good governance would be negatively associated with MHDs directly and indirectly through QoL.

H2: Perceived discrimination would be positively associated with MHDs directly and indirectly through QoL.

H3: Perceived social support would be negatively associated with MHDs directly and indirectly through QoL.

H4: QoL would be negatively associated with MHDs directly.

Methods

Study design and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted in Tabriz, Iran, from March to September 2022. The study targeted the general population attending primary healthcare centers in the city.

Setting

Tabriz, a major industrial city located in northwest Iran, served as the study location. With a population of approximately 1.64 million in 2022, the city is divided into 10 municipal districts, each containing numerous historic and culturally significant neighborhoods.

Study population

The study aimed to recruit participants from the general population residing in Tabriz, Iran. Individuals over 18 years old who resided within the city limits and were fluent in Persian were eligible to participate. Additional inclusion criteria included being registered with a healthcare centre and possessing the mental and physical capacity to complete the study. Individuals with intellectual disabilities and those diagnosed with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease according to the diagnosis of the family physician were excluded from the study.

Sample size and sampling method

To ensure sufficient statistical power for path analysis, the recommended ratio of 5–10 observations per parameter was considered [23]. In this study, employing path analysis to examine the relationships between variables involved multiplying the number of questionnaire items related to independent variables (79 parameters) by 9. To increase precision by 15% and account for potential sample attrition, the sample size was expanded to 817 participants. According to Wolf et al. [23], this sample is sufficient for the structural equation modeling technique used in the current research. A multistage stratified and cluster sampling strategy was adopted to recruit respondents. The process involved the following steps:

-

1.

District Selection: Three districts were randomly chosen from the 10 districts covered for primary healthcare by Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, ensuring representation of high, medium, and low socio-economic statuses.

-

2.

Cluster Identification: Within the selected districts, all primary healthcare centers were identified as clusters.

-

3.

Center Selection: Six primary healthcare centers were randomly chosen from each district.

-

4.

Quota Allocation: Based on the population served, a quota of participants was assigned to each selected center.

-

5.

Random Sampling: Finally, a random sampling approach was used to select residents referred to the centers for services. The study framework, sampling procedure, and response rate are further illustrated in Fig. 2.

Measures

Data were compiled using a self-reported questionnaire including sociodemographic variables, the General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28), WHOQOL-BREF, the Major Racial Discrimination Scale (MRDS), the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), and the Good Governance Scale (GGS).

Sociodemdemographic variables

The sociodemographic variables encompassed age, sex, marital status, education, job status, currency income, socioeconomic status, and housing situation.

Mental health disorders: general health questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) is a self-administered tool designed to assess mental health concerns in clinical settings. Participants reflect on their overall mental state in recent weeks by responding to 28 behavior statements on a 4-point scale ranging from “not at all” to “much more than usual” [24]. The survey comprises four main components: physical symptoms, anxiety and sleep problems, social impairment, and profound depression. Scores on the 28-item version can range from 0, indicating the lowest level of symptoms, to 84, symbolizing severe issues. According to Goldberg, individuals with cumulative scores of 23 or lower are considered non-psychiatric, while those scoring higher than 24 may fall into the psychiatric category based on the assessment [25]. The GHQ-28 has shown good internal consistency and test-retest reliability (0.90 and 0.58, respectively) in Iranian studies [26]. Internal consistency reliability in this study was excellent (α = 0.94).

Quality of life: WHOQOL-BREF

The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) was employed to measure QoL in this study. This widely-used instrument, available in over 40 languages, including Persian, comprises 26 items and two sub-scales: overall QoL and general health. To avoid redundancy, as some QoL questions overlapped with the mental health and social support questionnaire, we utilized seven specific items from the WHOQOL-BREF. These items include self-esteem, health services, transportation, living physical environment, security, leisure activity, and overall QoL. Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (an extreme amount). The total score ranges from 7 to 35, with higher scores indicating better QoL. The WHOQOL-BREF used in this study was translated and validated for Iranian use according to WHO guidelines [27]. The validity and reliability of the tool have been confirmed in previous Iranian studies [28, 29]. Additionally, the internal consistency reliability in our sample was excellent, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.87.

Discrimination: major racial discrimination scale

To assess the prevalence of significant discriminatory experiences among participants, we utilized the Multidimensional Racism and Discrimination Scale (MRDS) [30]. This instrument comprises 8 items with binary response options (“yes” or “no”), allowing participants to indicate whether they have encountered any of the following lifetime events based on their race or ethnicity, religion, age, or gender:

-

Denied employment opportunities (not hired for a job, denied a promotion, or fired).

-

Prevented from moving into a desired neighborhood.

-

Received lower-quality medical care.

-

Unfairly denied educational opportunities or discouraged by a teacher or advisor.

-

Stopped, searched, questioned, physically threatened, or abused by the police.

The MRDS has been employed in previous studies among women and adolescents in Iran [31, 32] and has demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.91). In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for the MRDS was 0.80.

Social support: multidimensional scale of perceived social support

Social support is often assessed using various tools. Among them, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS), developed by Zimet et al. in 1988, stands out as a widely used and reliable instrument [33]. The MSPSS comprises 12 items that measure perceived support from three key sources: family, friends, and a significant other (such as a spouse or best friend). Participants respond to these items on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (agree). The Persian version of the MSPSS has demonstrated good reliability and validity in previous research, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.82 [34]. In our study, the internal consistency of the MSPSS was further confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.90.

Good governance: good governance scale

To evaluate perceptions of good governance, we utilized the GGS adapted from Salminen and Norrbacka’s (2010) research on trust, good governance, and unethical behaviors in the Finnish public sector [35]. This questionnaire was designed to capture public citizens’ overall perspectives on the effectiveness of good governance practices. The scale comprises 23 items that assess five key dimensions of good governance including “rule of law”, “transparency”, “participation in decision-making”, “accountability”, “responsibility”, and “efficiency”. Participants responded to each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). The total score on the scale ranges from 23 to 115 points, with higher scores indicating a higher perceived level of good governance. The GGS has demonstrated good reliability in previous research, with a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.78 for the entire scale reported by Yousaf et al. [36]. In our study, the internal consistency of the Persian version of the scale was further confirmed with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.892.

Data collection

Following the acquisition of the necessary ethical approvals from Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, data collection commenced in March 2022. Two trained research assistants, one male and one female, administered the study questionnaires. Paper-based questionnaires were distributed in person at selected primary healthcare centers. After participants received healthcare services, they were invited to a private room to complete the questionnaires. Prior to participation, all individuals who provided written informed consent were briefed on the study aims and questionnaire completion procedures, and were assured of their anonymity and voluntary participation. Additionally, research assistants monitored questionnaire completion to minimize incomplete responses. The data collection period spanned from March 1st to September 25th, 2022, resulting in a high response rate of 92.9% (725 participants).

Data analysis

Data analysis was performed using SPSS-24.0 and Lisrel-7 software. Descriptive statistics such as frequency, percentage, mean, and standard deviation were initially employed to summarize all variables. Data normality was then verified through skewness and kurtosis values, and the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. To explore relationships between variables, a correlation matrix was constructed. All proposed measures were entered to identify significant bivariate relationships using two-tailed tests (p < 0.05). Direct correlations and significant associations with variables on the left-hand side informed the development of an initial hypothesized model. The subsequent main analysis involved a multiple mediator analysis using Lisrel Version 7. The model fit was evaluated using established criteria [37]:

-

Comparative Fit Index (CFI) ≥ 0.9.

-

Goodness of Fit Index (GFI) ≥ 0.9.

-

Bentler-Bonett Normed Fit Index (NFI) ≥ 0.9.

-

Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA) ≤ 0.05.

Results

Demographics of the study sample

A total of 817 questionnaires were distributed, resulting in 750 completed responses (a response rate of 91.8%). After excluding 25 participants who were below 15 years old or had incomplete questionnaires, the final sample consisted of 725 adults (50.2% men) aged between 18 and 87 years old (M = 42.82, SD = 14.43). The majority of the participants were married (77.4%). Further demographic details are presented in Table 1.

Descriptive of MHDs, discrimination, social support, QoL, and good governance

Table 2 presents the mean mental health, discrimination, social support, QoL, and good governance. The scoring system is designed such that higher values indicate poorer mental health, more frequent discrimination, lower QoL, and weaker good governance and social support. From the presented data, it can be noted that participants perceived low MHDs (mean = 32.11; SD = 13.54). Based on the Goldberg cut-off, 70.3% of the statistical population of this study suffers from psychiatric disorders. Regarding social support, they reported a moderate level of social support (mean = 36.33; SD = 6.15). Participants’ mean score of major racial discrimination is 3.94 ± 2.47, which indicates medium levels of discrimination among participants. Additionally, they had an average perception of good governance (mean = 55.69; SD = 19.54). Finally, the means of QoL were 18.80 out of 35.

Mental health disorders, discrimination, social support, QoL, and good governance associations

Prior to conducting path analysis, bivariate correlations were calculated to assess the relationships between the study variables (see Table 2). These analyses revealed a positive association between MHDs and major racial discrimination (r = 0.26, p < 0.001). Conversely, significant negative correlations were observed between MHDs and social support (r = -0.26, p < 0.001), QoL (r = -0.32, p < 0.001), and good governance scores (r = -0.11, p < 0.004).

To further investigate the hypothesized effects of good governance, social support, and major racial discrimination on MHDs, mediated by QoL, we employed structural equation modeling (SEM). Figure 3 displays the results of the model as fit, and Table 3 reports the full results of direct, indirect, and total effects. The model fit indices indicated a good overall fit (χ2/df = 2.71, p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.034, GFI = 0.98, NFI = 0.95, IFI = 0.98, CFI = 0.96).

The results revealed that good governance had no direct effect on MHDs. However, it displayed a significant negative indirect effect (β = -0.05, p < 0.01), partially supporting hypothesis 1. This suggests that good governance can contribute to improved mental health by 5% through its positive influence on QoL.

Supporting hypothesis 2, major racial discrimination had a positive direct and indirect effect on MHDs (β = 0.24). In other words, for every unit increase in the discrimination score, MHDs worsened by 0.24 units, partly mediated by a decrease in QoL. In line with hypothesis 3, social support significantly predicted lower MHDs directly (β = -0.17, p < 0.01) and indirectly through its positive impact on QoL (β = -0.06, p < 0.01). Furthermore, QoL exhibited a negative indirect effect on MHDs (β = -0.24, p < 0.01), indicating that a one-unit increase in QoL score was associated with a 0.24-unit decrease in MHDs.

Discussion

This study investigated the mediating role of QoL in the relationship between good governance, social support, perceived discrimination, and MHDs among residents of Tabriz, Iran. The findings suggest that QoL significantly mediates the impact of these factors on MHDs, highlighting its crucial role in mental health outcomes. These results provide valuable insights for developing targeted interventions aimed at improving the population’s mental health. By focusing on enhancing QoL through promoting good governance, fostering social support networks, and addressing discriminatory practices, we can contribute to a more mentally healthy community.

Prevalence of MHDs

This study identified a significantly higher prevalence of MHDs in Tabriz, Iran, compared to national averages [38, 39]. Participants in Tabriz exhibited a concurringly high mean score of 32.11 on the GHQ-28, with 70.3% classified as having MHDs. This contrasts sharply with the lower rates of 23.4% and 37.1% reported in previous nationwide Iranian studies [38, 39]. Several factors may explain this discrepancy. While all studies utilized the same GHQ-28 instrument, demographic differences in the study populations could be influential. Additionally, research suggests regional variations in mental disorder distribution, cultural influences on mental health perception, and discrepancies in measurement and diagnosis practices can impact prevalence rates [40,41,42]. Furthermore, data collection occurred after the second and third waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, potentially influencing the observed MHDs. Notably, Tabriz, as the capital of East Azerbaijan, experienced a high rate of divorce and domestic violence during the pandemic, potentially contributing to the elevated MHDs [43]. The significantly higher MHDs prevalence in Tabriz compared to the national average warrants further investigation. This finding highlights a serious public health concern that, if left unaddressed, could lead to significant problems for individuals. Future research is crucial to comprehensively understand the factors contributing to the high MHDs prevalence in Tabriz and develop effective strategies for intervention.

The impact of social support on MHDs and the mediation role of QoL

This study confirms the significant positive impact of social support on MHDs and QoL. The findings suggest that enhancing QoL through social support can lead to improved overall mental health. This aligns with extensive research demonstrating the link between social support and positive mental health outcomes and the utilization of mental health services [44,45,46,47]. Previous studies have highlighted the crucial role of diverse social support sources, including individuals and services, in fostering social connections and community integration for individuals experiencing mental health challenges [48, 49]. A study among Nepalese migrants in Japan, for example, found a negative correlation between perceived social support from family, friends, and significant others and psychological distress [50]. Furthermore, research conducted in developed countries has consistently shown that social support positively impacts QoL and improves overall health and mental status [51,52,53]. This aligns with the established role of social support in enhancing QoL across various populations [47]. Therefore, individuals facing mental health challenges are strongly encouraged to cultivate a strong social support network and actively utilize available social support resources to mitigate the detrimental effects of their condition.

The impact of perceived discrimination on MHDs and the mediation role of QoL

This study found a positive relationship between discrimination and MHDs, with QoL acting as a mediating factor. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating the detrimental impact of discrimination on mental health. Ayalon and Gum’s study (2011) in the United States revealed a link between everyday discrimination and negative mental health markers among older adults [54]. Similarly, a systematic review found that reported instances of discrimination are associated with poorer mental health, physical health outcomes (including early illness signs, health behaviors, healthcare utilization, and treatment adherence), and QoL [55]. Furthermore, research conducted among refugees and migrants in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic showed that perceived discrimination significantly impacted anxiety, depression, and hyper-arousal symptoms [56]. Additionally, studies in the United States have demonstrated that self-reported racial discrimination is associated with poor health-related QoL outcomes [57] and acts as a pathway to influence the mental health component of QoL [53]. Considering this body of evidence, developing interventions to reduce the perception of discrimination is crucial for promoting mental health and improving overall well-being.

The impact of good governance on MHDs and mediation role of QoL

This study revealed that good governance has an indirect negative relationship with MHDs, with QoL acting as a mediating factor. This finding aligns with existing research demonstrating the positive impact of effective governance on health and QoL. Previous studies have shown that countries with better governance standards tend to experience improved health outcomes for women, including lower mortality rates and higher QoL [8]. Additionally, Menon-Johansson (2005) [58] identified a significant association between weak governance and high HIV prevalence, highlighting the broader health implications of governance practices. However, Mikkelsen-Lopez et al. (2011) [59] caution that improvements in governance may not automatically translate to overall health system enhancements due to the influence of various non-governance factors. Furthermore, research conducted in Spain found a positive correlation between QoL and specific aspects of good governance, such as participation and financial accountability [53]. Recognizing the complex interplay between governance and health system operations is crucial for understanding the observed relationships. The present study emphasizes the importance of promoting good governance as a key step in enhancing mental health. This suggests that public health initiatives should address societal frameworks to establish a strong foundation for effective healthcare interventions.

The impact of QoL on MHDs

The path analysis indicated a direct positive relationship between QoL and MHDs. This suggests that an improvement in QoL leads to a decrease in MHDs, highlighting the influence of QoL on psychological well-being. This finding aligns with previous research demonstrating the positive association between QoL and mental health. Özabaci (2010) found a significant link between overall QoL assessments and depression scores among high school students in Turkey [60]. Similarly, a study among health professions students in Saudi Arabia revealed a strong correlation between higher QoL and lower perceived stress [61]. Furthermore, Bdier et al. (2023) reported a negative correlation between QoL and various mental health outcomes (depression, stress, and anxiety) in a sample of Palestinian adults [62]. This inverse relationship can be understood through the lens of individualistic QoL evaluations, where individuals subjectively assess their well-being across various domains, including social, physical, and emotional aspects [63]. Given the complex challenges faced by Iranians in different areas of their lives, such as social connections, psychological health, and financial stability, it is plausible that individuals experiencing a perceived decline in QoL may be at increased risk for developing MHDs like depression, stress, and anxiety.

Limitations of the study

This study acknowledges several limitations that require careful consideration when interpreting its findings. Firstly, the cross-sectional design employed in this research restricts the ability to establish causal relationships between the observed variables. While the study identifies associations, it cannot definitively determine cause and effect. Secondly, the sample population was recruited solely from Tabriz, Iran, which is predominantly of Turkish ethnicity. This raises concerns about generalizability, as the findings may not be directly applicable to other ethnicities. Further research involving diverse populations is recommended for a more comprehensive understanding. Thirdly, the reliance on self-reported questionnaires introduces the potential for recall bias. Participants’ responses may be influenced by their attitudes and memories, potentially impacting the accuracy of the data. Finally, the GHQ-28, while a valuable tool, is a self-report instrument and cannot substitute for standardized diagnostic assessments. Additionally, it is limited to evaluating the current state of mental health and cannot provide insight into past experiences with MHDs.

Conclusion

This study developed an empirical model that clarifies the relationships between MHDs and social determinants of health in the Iranian adult population. The model incorporates good governance, perceived discrimination, social support, and QoL as mediating factors. The findings reveal an unfavorable mental health status among the study participants. Additionally, the model suggests that good governance, social support, and reduced discrimination can positively impact mental health through improved QoL. Therefore, promoting good governance, fostering social support, and mitigating perceived discrimination are crucial public health priorities. Further research is warranted to evaluate the effectiveness of educational and counseling interventions in improving MHDs and QoL levels among adults.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- MDSs:

-

Mental health disorders

- DALYs:

-

disability-adjusted life years

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- QoL:

-

Quality of life

- GHQ-28:

-

General Health Questionnaire

- MRDS:

-

Major Racial Discrimination Scale

- MSPSS:

-

Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support

- GGS:

-

Good Governance Scale

References

Vigo D, Thornicroft G, Atun R. Estimating the true global burden of mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(2):171–8.

Arias D, Saxena S, Verguet S. Quantifying the global burden of mental disorders and their economic value. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;54:101675.

Collaborators GMD. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9(2):137–50.

Mirghaed MT, Gorji HA, Panahi S. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Iran: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Prev Med. 2020;11:1–7.

Choda N, Wakai K, Naito M, Imaeda N, Goto C, Maruyama K, et al. Associations between diet and mental health using the 12-item General Health Questionnaire: cross-sectional and prospective analyses from the Japan Multi-institutional Collaborative Cohort Study. Nutr J. 2020;19:1–14.

Prokosch C, Fertig AR, Ojebuoboh AR, Trofholz AC, Baird M, Young M, et al. Exploring associations between social determinants of health and mental health outcomes in families from socioeconomically and racially and ethnically diverse households. Prev Med. 2022;161:107150.

Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. WHO Document Production Services; 2010.

Mohammadzadeh Y. A study about the effect of good governance on the women’s health in upper-middle income countries with GMM approach. Q J Woman Soc. 2020;11(41):29–52.

Upadhaya N, Jordans MJ, Pokhrel R, Gurung D, Adhikari RP, Petersen I, et al. Current situations and future directions for mental health system governance in Nepal: findings from a qualitative study. Int J Mental Health Syst. 2017;11:1–12.

Williams JS, Cunich M, Byles J. The impact of socioeconomic status on changes in the general and mental health of women over time: evidence from a longitudinal study of Australian women. Int J Equity Health. 2013;12(1):1–11.

Pengpid S, Peltzer K. Perceived discrimination and health outcomes among middle-aged and older adults in India: results of a national survey in 2017–2018. BMC Geriatr. 2021;21:1–10.

Mouzon DM, Taylor RJ, Keith VM, Nicklett EJ, Chatters LM. Discrimination and psychiatric disorders among older African americans. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017;32(2):175–82.

Ra CK, Huh J, Finch BK, Cho Y. The impact of perceived discrimination on depressive symptoms and the role of differentiated social support among immigrant populations in South Korea. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18:1–9.

Sims M, Diez-Roux AV, Gebreab SY, Brenner A, Dubbert P, Wyatt S, et al. Perceived discrimination is associated with health behaviours among african-americans in the Jackson Heart Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(2):187–94.

Schunck R, Reiss K, Razum O. Pathways between perceived discrimination and health among immigrants: evidence from a large national panel survey in Germany. Ethn Health. 2015;20(5):493–510.

Yang T-C, Chen I-C, Choi S-w, Kurtulus A. Linking perceived discrimination during adolescence to health during mid-adulthood: self-esteem and risk-behavior mechanisms. Soc Sci Med. 2019;232:434–43.

Mougenot B, Amaya E, Mezones-Holguin E, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Cabieses B. Immigration, perceived discrimination and mental health: evidence from Venezuelan population living in Peru. Globalization Health. 2021;17:1–9.

Holden L, Lee C, Hockey R, Ware RS, Dobson AJ. Longitudinal analysis of relationships between social support and general health in an Australian population cohort of young women. Qual Life Res. 2015;24:485–92.

Hutten E, Jongen EM, Vos AE, van den Hout AJ, van Lankveld JJ. Loneliness and mental health: the mediating effect of perceived social support. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(22):11963.

Group W. Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):551–8.

Kalfoss MH, Reidunsdatter RJ, Klöckner CA, Nilsen M. Validation of the WHOQOL-Bref: psychometric properties and normative data for the Norwegian general population. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:1–12.

Eslam Parast N, Taştekin Ouyaba A. The impact of the demographic and migration process factors of refugee women on quality of life and the mediating role of mental health. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022;58(2):785–94.

Wolf EJ, Harrington KM, Clark SL, Miller MW. Sample size requirements for structural equation models: an evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educ Psychol Meas. 2013;73(6):913–34.

Goldberg DP, Hillier VF. A scaled version of the General Health Questionnaire. Psychol Med. 1979;9(1):139–45.

Goldberg D, Oldehinkel T, Ormel J. Why GHQ threshold varies from one place to another. Psychol Med. 1998;28(4):915–21.

Malakouti SK, Fatollahi P, Mirabzadeh A, Zandi T. Reliability, validity and factor structure of the GHQ-28 used among elderly iranians. Int Psychogeriatr. 2007;19(4):623–34.

Organization World Health. Programme on mental health: WHOQOL user manual. World Health Organization; 1998.

Nedjat S, Montazeri A, Holakouie K, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R. Psychometric properties of the Iranian interview-administered version of the World Health Organization’s quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF): a population-based study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):1–7.

Usefy A, Ghassemi GR, Sarrafzadegan N, Mallik S, Baghaei A, Rabiei K. Psychometric properties of the WHOQOL-BREF in an Iranian adult sample. Commun Ment Health J. 2010;46:139–47.

Williams DR, Yu Y, Jackson JS, Anderson NB. Racial differences in physical and mental health: Socio-economic status, stress and discrimination. J Health Psychol. 1997;2(3):335–51.

Googhary NS, Foroughan M, Mohammadi F, Farhadi A, Nazari S. Psychometric properties of persian version of everyday discrimination scale and correlation with physical health in Iranian older women. Crescent J Med Biol Sci. 2020;7(2):195–200.

Pazhouhi S. Online and offline Bullying/Harassment and perceived Racial/Ethnic discrimination among Iranian adolescents. Can J School Psychol. 2023;38(4):333–48.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41.

Bagherian-Sararoudi R, Hajian A, Ehsan HB, Sarafraz MR, Zimet GD. Psychometric properties of the Persian version of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support in Iran. Int J Prev Med. 2013;4(11):1277.

Salminen A, Ikola-Norrbacka R. Trust, good governance and unethical actions in Finnish public administration. Int J Public Sector Manag. 2010;23(7):647–68.

Yousaf M, Ihsan F, Ellahi A. Exploring the impact of good governance on citizens’ trust in Pakistan. Government Inform Q. 2016;33(1):200–9.

Byrne BM. Structural equation modeling with Mplus: basic concepts, applications, and programming. routledge; 2013.

Bahrami M, Jalali A, Ayati A, Shafiee A, Alaedini F, Saadat S, et al. Epidemiology of mental health disorders in the citizens of Tehran: a report from Tehran Cohort Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23(1):267.

Noorbala AA, Faghihzadeh S, Kamali K, Yazdi SAB, Hajebi A, Mousavi MT, et al. Mental health survey of the Iranian adult population in 2015. Arch Iran Med. 2017;20(3):0.

Weich S, Holt G, Twigg L, Jones K, Lewis G. Geographic variation in the prevalence of common mental disorders in Britain: a multilevel investigation. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(8):730–7.

Van Os J, Driessen G, Gunther N, Delespaul P. Neighbourhood variation in incidence of schizophrenia: evidence for person-environment interaction. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176(3):243–8.

Heim E, Wegmann I, Maercker A. Cultural values and the prevalence of mental disorders in 25 countries: a secondary data analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2017;189:96–104.

Khodavirdipour A, Samadi M. Pandemic consequences: an increase in divorce rate, domestic violence, and extramarital affairs at the time of COVID-19 pandemic: a sad persian story. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1100149.

Bjørlykhaug KI, Karlsson B, Hesook SK, Kleppe LC. Social support and recovery from mental health problems: a scoping review. Nordic Social work Res. 2022;12(5):666–97.

Terry R, Townley G. Exploring the role of social support in promoting community integration: an integrated literature review. Am J Community Psychol. 2019;64(3–4):509–27.

Wang J, Mann F, Lloyd-Evans B, Ma R, Johnson S. Associations between loneliness and perceived social support and outcomes of mental health problems: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):1–16.

Shen T, Li D, Hu Z, Li J, Wei X. The impact of social support on the quality of life among older adults in China: an empirical study based on the 2020 CFPS. Front Public Health. 2022;10:914707.

Salehi A, Ehrlich C, Kendall E, Sav A. Bonding and bridging social capital in the recovery of severe mental illness: a synthesis of qualitative research. J Mental Health. 2019;28(3):331–9.

Terry R, Townley G, Brusilovskiy E, Salzer MS. The influence of sense of community on the relationship between community participation and mental health for individuals with serious mental illnesses. J Community Psychol. 2019;47(1):163–75.

Khatiwada J, Muzembo BA, Wada K, Ikeda S. The effect of perceived social support on psychological distress and life satisfaction among Nepalese migrants in Japan. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(2):e0246271.

Shao B, Song B, Feng S, Lin Y, Du J, Shao H, et al. The relationship of social support, mental health, and health-related quality of life in human immunodeficiency virus-positive men who have sex with men: from the analysis of canonical correlation and structural equation model: a cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2018;97(30):e11652.

Kong L-N, Zhang N, Yuan C, Yu Z-Y, Yuan W, Zhang G-L. Relationship of social support and health-related quality of life among migrant older adults: the mediating role of psychological resilience. Geriatr Nurs. 2021;42(1):1–7.

Achuko O, Walker RJ, Campbell JA, Dawson AZ, Egede LE. Pathways between discrimination and quality of life in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2016;18(3):151–8.

Ayalon L, Gum AM. The relationships between major lifetime discrimination, everyday discrimination, and mental health in three racial and ethnic groups of older adults. Aging Ment Health. 2011;15(5):587–94.

Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA, Vu C. Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Serv Res. 2019;54:1374–88.

Spiritus-Beerden E, Verelst A, Devlieger I, Langer Primdahl N, Botelho Guedes F, Chiarenza A, et al. Mental health of refugees and migrants during the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of experienced discrimination and daily stressors. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(12):6354.

Bergeron G, De La Lundy N, Gould LH, Liu SY, Levanon Seligson A. Association between racial discrimination and health-related quality of life and the impact of social relationships. Qual Life Res. 2020;29:2793–805.

Menon-Johansson AS. Good governance and good health: the role of societal structures in the human immunodeficiency virus pandemic. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2005;5(1):1–10.

Mikkelsen-Lopez I, Wyss K, de Savigny D. An approach to addressing governance from a health system framework perspective. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2011;11(1):1–11.

Özabacı N. Quality of life as a predictor of depression. Procedia-Social Behav Sci. 2010;2(2):2458–63.

Alkatheri AM, Bustami RT, Albekairy AM, Alanizi AH, Alnafesah R, Almodaimegh H, et al. Quality of life and stress level among health professions students. Health Professions Educ. 2020;6(2):201–10.

Bdier D, Veronese G, Mahamid F. Quality of life and mental health outcomes: the role of sociodemographic factors in the Palestinian context. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):16422.

Shek DT. Protests in Hong Kong (2019–2020): a perspective based on quality of life and well-being. Appl Res Qual Life. 2020;15:619–35.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the PHC centers and participants for sharing their space and time with the researchers.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EK and SEK was involved in conceptualization, design, data analysis, and interpretation, and also drafted the full manuscript. MA, EM and MA participated in conceptualization, design, data collection, and data interpretation, and were involved in manuscript revisions. JS contributed in the data analysis and revising and editing the manuscript. All authors have given their approval for the final version.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This research followed the Declaration of Helsinki and has been submitted to the Ethics Committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences and has been approved (IR.TBZMED.REC.1401.063). Written informed consent for this study has been obtained from all participants. The participants learned about the study’s aim, data confidentiality, and voluntary involvement. All methods complied with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kakemam, E., Mohammadpour, E., Karimi, S.E. et al. The relationship between good governance, social support, and perceived discrimination with mental health through the mediation role of quality of life: a cross-sectional path analysis in Iran. BMC Public Health 24, 2306 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19806-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19806-x