Abstract

Background

The global public health issue of diminishing physical fitness among adolescents has gained increasing attention. The impact of parents’ negative emotions or pressure regarding adolescents’ educational aspirations may have a passive impact on the quality of life and adaptation of adolescents in and out of school, and ultimately harm their physical health. This study aims to explore whether parent-child discrepancies in educational aspirations influence physical fitness in adolescents through school adaptation and quality of life.

Methods

Participants consisted of 9,768 students, males 4,753(48.7%), females 5,015(51.3%), aged 11–19 years, males 14.3 ± 1.92, females 14.4 ± 1.93. The educational aspirations were gauged using a six-point scale for expectation scores. Physical fitness assessments were based on criteria from the National Student Physical Fitness and Health Survey. School adaptation was evaluated using the School Social Behaviors Scale-2. Quality of life for adolescents was measured using Chinese version of the Quality of Life Scale for Children and Adolescents. To analyze the multiple mediating effects, structural equation models were used, and 95% confidence intervals were determined through bootstrap methods.

Results

The results illustrated that school adaptation and quality of life played a significant mediating role in the effect of parent-child discrepancies in educational aspirations and physical fitness. There were three intermediary paths were confirmed: (1) discrepancies in educational aspirations → school adaptation → physical fitness (β=-0.088 SE = 0.021; p<0.01; 95% CI: -0.135, -0.05); (2) discrepancies in educational aspirations → quality of life → physical fitness (β=-0.025; SE = 0.011; p = 0.010; 95% CI: -0.050, -0.006); (3) discrepancies in educational aspirations → school adaptation→ quality of life → physical fitness (β=-0.032; SE = 0.014; p = 0.011; 95% CI: -0.061, -0.007).

Conclusion

This study suggests that parents should reduce negative emotions and pressure regarding adolescents’ academic aspirations may help their children get better physical fitness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The current decline in physical fitness (PF) among adolescents has emerged as a global public health concern. Levels of physical fitness during childhood and adolescence can affect their adult health [1] and serves as a predictive indicator for morbidity and mortality rates [2]. Poor PF in adolescents is associated with an increased risk of type 2 diabetes and obesity [3], and metabolic disorders [4]. It also contributes to a higher incidence of symptoms related to depression and anxiety [5, 6], which may persist into adulthood [7]. Although there has been an overall improvement in the PF levels of adolescents, the developmental trend remains less optimistic [8]. According to the results of the eighth National Students’ Physical Health Survey released by China’s Ministry of Education in 2021, only 17.7% of students, aged 13–22, attained a “good” or “excellent” level [9], only 33% of students met the national standards, which could yield critical impact on adolescents’ academic performance [10], physical and mental health [5, 11, 12].

Educational aspirations are defined as the level of education a person wants to attain [13]. Parental educational aspirations serve as both a source of academic support and a potential stressor for adolescents. Whether parental educational aspirations act as a motivating or a pressure factor depends on the discrepancies between adolescents’ own aspirations and those of their parents [14]. According to the Identity Control Theory [15], persistent and unresolved differences between environmental inputs and personal identity criteria can cause psychological distress in individuals. Parental educational expectations can be considered environmental inputs, while self-educational expectations can be seen as identity criteria. Regardless of whether the input is more positive or negative than the identity criteria, such differences can result in distress, and the greater the difference, the greater the distress [16]. Psychological distress caused by larger parent-child discrepancies in educational aspirations (PCDEA) may impact school adaptation (SA) and quality of life (QoL) of adolescents [17]. At the same time, increased perceived stress in adolescents is accompanied by declining PF, such as aerobic fitness [18]. Notably, perceived educational aspiration discrepancies among adolescents can have a more direct adverse impact on them than actual discrepancies. Therefore, this study primarily discusses adolescent perceived educational aspiration discrepancies.

School adaptation refers to the ability to adapt to the requirements and characteristics of the school environment, experiencing comfort, engagement, and acceptance, which is the integration of cognition, attitudes, and behaviors [19]. The understanding of adolescents’ school adaptation status typically involves examining two aspects: social competence and antisocial behavior [20, 21]. The bioecological model emphasizes the ongoing interaction between developing individuals and their surrounding environments [22], and adapting to school is foundational for their healthy growth [23]. Some studies found that currently, approximately 70% of Chinese adolescents experience varying degrees of study-weariness, highlighting the prevalent issue of poor SA among adolescents. Positive parent-child interactions and academic support can significantly predict SA [24]. Low self-esteem, poor communication, and insecure attachment [25] caused by PCDEA are associated with adolescents’ SA [24]. Poor SA, reflected by poor social competence [26] and antisocial behaviors [27], is correlated with adolescent obesity, which is an important indicator of adolescents’ PF. However, the relationship with overall PF levels remains to be explored. Meanwhile, poor SA can directly decrease adolescents’ sense of belonging [28], induce daytime sleepiness [29], reduce opportunities for social interactions, and diminish enthusiasm for participating in physical activities [30], this may be an important reason for affecting the QoL of adolescents.

QoL is defined as people’s perceptions of their position in life in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live, and in relation to their goals, expectation, standards, and concerns [31], which is a commonly used positive indicator applicable to all stages of human life [32]. Research on adolescents suggests that QoL involves initiating and maintaining a positive life healthy cycle of well-being, which heavily relies on stable family relationships and effective family functioning [33]. Previous studies showed that the impairment of family relationship and function caused by elevated PCDEA can negatively impact adolescents’ life satisfaction. The adverse effects on the functioning and mental health are also contributing factors to the reduction in the QoL among adolescents. Many studies have confirmed significant associations between QoL and adolescents’ muscular strength [34], cardiorespiratory endurance [35] and other factors related to PF [36], particularly highlighting strong associations between various dimensions of health-related QoL and PF [37].

Current research mainly focused on parental expectations or adolescents’ self-expectation, adolescents’ academic performance, academic outcomes [14], health risk behaviors [38], and mental health [39]. There was still little known to the association of PCDEA, PF, QoL and SA. The research hypothesized that PCDEA directly impacts PF of adolescents and indirectly affects the PF of adolescents through the mediating pathways of SA and QoL respectively. Moreover, PCDEA also impacts PF of adolescents through the chain mediation pathway of SA and QoL. Meanwhile, gender [40, 41], only-child status [42, 43], past experience as a student leader, and family economic status [44, 45] have been exposed to influence the relationship between variables, so they will be included as covariates in the model of this study. The purpose of this study is to examine whether PCDEA and PF associated with SA and QoL through the mediating pathways and construct a multiple mediating model. In addition, previous studies have shown intense interest in the gender differences concerning adolescent PF [46], SA [47], and QoL [48]. We will also conduct a simple gender difference analysis of the main variables and basic personal information in the descriptive statistics section to better understand the sample characteristics. Through a deep understanding of the relationships between multiple pathways, this research will provide insights and targeted recommendations for promoting adolescent health.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Data for this study were derived from the Database of Youth Health (DYH) in National Population Health Data Center, a longitudinal Database of Chinese adolescents’ health. DYH is the publicly shared dataset on the health and health-related behaviors of Chinese adolescents, comprising comprehensive data from several years of middle school and high school cohorts [49, 50]. Utilizing the population proportionate sampling (PPS) method, schools were randomly selected to be based on geographical, demographic, and socio-economic level in Shandong Province, China. A total of 9,768 adolescents (14.4 ± 1.93 years) were selected in the 2020–2021 semester from 62 middle schools and 32 high schools from 9 districts, including 4,753 males (14.3 ± 1.92 years) and 5,015 females (14.4 ± 1.93 years).

Measures

Parent-child discrepancies in educational aspirations

PCDEA among adolescents were measured by asking them about their own educational aspirations and the educational aspirations they perceived from their parents [16, 51]. PCDEA were categorized into six levels (1 = junior high school or below; 6 = doctoral degree). The absolute difference between these two values was calculated as the PCDEA score, 0 ≤ PCDEA ≤ 5.

Physical fitness

The National Student Physical Fitness and Health 2014 (NSPFH 2014) was used to evaluate [52]. (a) body mass index (BMI, unit: kg/m2); (b) vital capacity (unit: ml); (c) 50-m sprint (unit: minutes’ seconds’’); (d) sit and reach (unit: cm); (e)standing long jump (unit: cm); (f) pull-ups (unit: times; tested only for males); (g) bent-leg sit-ups (unit: times/minute; tested only for females); (h) 1000-m / 800-m running (unit: minutes’ seconds’’).

School adaptation

SA was measured using the School Social Behavior Scale-2 (SSBS-2), which was originally developed by Merrell [20, 21]. SSBS-2 was employed to screen and evaluate social competence and antisocial behavior in school students. In social competence subscale, peer relation (PR) dimension was used to assess the significant social skills and characteristics related to the establishment of positive relationships with classmates. Self-management (SM) dimension measured behaviors such as self-control, cooperation, adherence to school rules and expectations. Academic behavior (AB) dimension was used to measure adolescents’ academic performance and engagement in learning tasks, In antisocial behavior subscale. Hostile-irritable (HI) dimension encompassed behaviors characterized by self-centeredness, irritability and annoyance leading to rejection by classmates. Antisocial-aggressive (AA) dimension measured openly violating school rules, threatening or hurting others, which may evolve into conduct disorders and delinquent behaviors. Defiant-disruptive (DD) dimension reflected impulsive behaviors during school activities, or having excessive and inappropriate demands on others. SSBS-2 was testified by the Cronbach’s α = 0.897, KMO = 0.821, χ²=62326.379, demonstrating good reliability and validity.

Quality of life

QoL is a self-report questionnaire called Quality of Life Scale for Children and Adolescents (QLSCA), which designed by Kowalski et al. [53, 54] to assess QoL in children and adolescents. The 49-item Chinese version QLSCA has been proven to be suitable for Chinese adolescents [55]. QLSCA including social psychology function, physio-mental health, living environment and satisfaction of living quality. Social psychology function involved teacher-student relationships, peer relationships, parent-child relationships, learning abilities and attitudes, and self-concept. Physio-mental health encompassed physical sensations, negative emotions, and attitudes toward schoolwork. Living environment included the convenience of daily life, opportunities for activities, and physical activity. Satisfaction of living quality assessed self-satisfaction and other aspects of living quality. QoL was tested by the Cronbach’s α = 0.903, KMO = 0.904, Bartlett test χ²=58189.095, demonstrating good reliability and validity.

Statistical analyses

All data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or relevant statistical measures, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Structural equation model (SEM) was employed to explore the direct and indirect relationships among PCDEA, PF, SA, and QoL. The model was adjusted for gender, only-child status, past experience as a student leader, and family economic status. To validate the model’s applicability, SEM and bootstrapping methods were utilized to test the significance of the mediating effects. When the sample size was 2000, and the 95% confidence interval does not include 0, it indicates that there was a mediating effect. STATA 17.0, SPSS 26.0 and AMOS 24.0 were used for data processing and analysis.

Results

Participants characteristics

This study analyzed a sample of 9,768 participants (Table 1) and founded that the age of participants ranged from 11 to 19 years, with an average age of 14.37 years. Among them, there were 4753 males (48.66%) and 5015 females (51.34%). A total of 6120 participants were in middle schools (62.65%), and 3648 were in high schools (37.35%). Significant gender differences (p < 0.05) were observed in the current educational stage, only-child status, father and mother educational level, family economic status, PCDEA, SA, QoL, and PF. However, there were no significant gender differences in age. More than half of the parents had an education level at or below junior high school. Males were more likely to be only children than girls, and had significantly higher scores in PCDEA and QoL. Females had a higher proportion of families with a socio-economic status at a moderate level or above, and had significantly higher scores in SA and PF.

Preliminary analysis

Table 2 presents that PCDEA were significantly negatively correlated with SA (β=-0.111, p < 0.001) and QoL (β=-0.058, p < 0.001). SA was significantly positively correlated with QoL (β = 0.666, p < 0.001) and PF (β = 0.066, p < 0.001). QoL was significantly positively correlated with PF (β = 0.036, p = 0.014). These relationships indicated that adolescents with larger PCDEA were more likely to experience poor SA and QoL, poor SA and QoL were associated with worse PF. Additionally, poor SA was linked to lower QoL, exacerbating the adverse impact on the PF of adolescents.

Mediation analysis

Table 3 presents the chain mediating effects of SA and QoL on the relationship between PCDEA and PF. the result showed that there was no direct effect of PCDEA on PF. However, each indirect path’s confidence interval excluded zero, explaining the multiple mediating role of SA and QoL in the relationship between PCDEA and PF. PCDEA had an indirect effect on PF through SA, with a mediation effect of -0.088. There was also an indirect effect of PCDEA on PF through QoL, with a mediation effect of -0.025. Furthermore, PCDEA exerted a chained indirect effect on PF through both SA and QoL, with a mediation effect of -0.032. The total effect was − 0.145, with the sole mediation effect of SA accounting for 60.69%, the sole mediation effect of QoL accounting for 17.24%, and the continuous path through SA and QoL accounting for 22.07%.

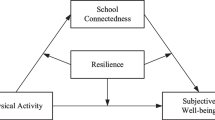

Using PCDEA as the independent variable, PF as the dependent variable, and SA and QoL as mediator variables, the path results are illustrated in Fig. 1. As a result, the structural model was verified as a good fit, and all the indices fulfilled the criteria: NFI = 0.927, GFI = 0.915, CFI = 0.928, RMSEA = 0.064, SRMR = 0.057.

Discussion

This study revealed that there was no direct effect of PCDEA on the PF of adolescents. However, PCDEA had indirect impacts on PF of adolescents through SA and QoL. Specifically, higher PCDEA directly negatively influenced both SA and QoL, and indirectly decreased PF of adolescents through the pathways of both SA and QoL. Additionally, poor SA negatively affected QoL for adolescents, thereby adversely impacting PF. This suggested that reducing PCDEA is a beneficial approach to improving SA, QoL, and PF among adolescents.

PCDEA in this study indirectly influenced PF of adolescents through SA, which suggests that discrepancies in educational aspirations between adolescents and their parents may lead to lesser SA, subsequently affecting PF. The intergenerational stake hypothesis states that parents and children always view the same interactions and behaviors from different perspectives [17]. Regardless of the sources of effective parenting or family processes, parent-child discrepancies can predict adolescents’ self-control abilities [56], which is a crucial factor influencing their social competence in the school environment. Additionally, these discrepancies often mean poor parent-child relationships, ineffective parental discipline, and coercive communication, which contribute to antisocial behaviors, a significant manifestation of school maladaptation in adolescents. The mechanism can be explained by Patterson’s Coercion Theory [57], which elucidated how parents unintentionally reinforce oppositional and aggressive behaviors in children through strict and inconsistent parenting, leading to the persistence of negative behaviors in children. The coercive cycle may stabilize and become a consistent pattern of interaction, extending into environments beyond the family, such as the school environment [58]. This may be an important reason for the PCDEA affecting adolescents’ SA. That is, adolescents learn how to handle conflicts with others at school by participating in social interactions within the family and observing the dialogue between their parents [59]. This can lead to adolescents triggering or intensifying conflicts in the school environment, making it challenging for them to adapt well to school, and it is difficult to establish and properly handle good relationships with school friends. School maladaptation can reinforce unhealthy behavior choices in adolescents, potentially leading to physical injuries such as trauma, fractures, internal injuries through involvement in intense physical conflicts and violent behaviors [60], as well as other behaviors that lead to high levels of chronic stress may increase susceptibility to related diseases [61].

PCDEA indirectly impacted PF of adolescents through their QoL in this study, which indicates that differences in educational aspirations between adolescents and their parents may lead to a decline in their QoL, subsequently affecting their PF. Adolescence is considered a crucial period for identity formation, as mentioned earlier in the Identity Control Theory [15], persistent and unresolved discrepancies between environmental inputs and personal identity standards lead to psychological distress. Regardless of whether the inputs are more positive or negative than the identity standards, such discrepancies cause suffering, with greater discrepancies resulting in more significant distress. Concerning educational identity, adolescents’ educational aspirations can be considered ideal self-identity standards, while parents’ aspirations for adolescents’ education serve as environmental inputs. As adolescents’ QoL relies on stable family relationships, the distress caused by PCDEA becomes a crucial factor influencing their QoL. From a socio-psychological adaptation and physio-mental health perspective, the tension and disharmony in the family atmosphere caused by such discrepancies may have a lasting and intense negative impact on the adolescents’ QoL. Studies indicated that discrepancies in aspirations between parents and children reflect both the autonomy support granted by parents and the autonomous development of adolescents [62]. Parental psychological control influences adolescent autonomy, leading them to question their abilities, ultimately resulting in reduced self-efficacy [63]. If parental expectations are excessively high or low, it implies a reduction in the autonomy granted to adolescents in their development, leading to confusion in self-perception and damage to self-esteem. This not only impairs the socio-psychological adaptation of adolescents but also becomes a crucial factor affecting their QoL. Research indicates that the QoL in adolescents is associated with PF [64]. In the study by Leibinger and colleagues [35], higher levels of health-related QoL were correlated with better cardiorespiratory health scores. Specifically, higher scores in domains such as physical and mental health, autonomy, and parental and school environments were associated with longer running distances. Additionally, higher level of PF, social support, peers, and school environment were linked to better sit-up performance. Moreover, poor QoL is associated with sleep issues [65], such as insomnia or irregular sleep patterns, which are crucial factors impacting adolescent growth, immune function, and cardiovascular health. Although current research on the directional relationship between QoL and PF is rare, we can reasonably infer based on existing studies that, adolescents with higher QoL tend to have more time, opportunities, and interest in participating in physical activities. They also have more scientifically informed means to monitor and maintain their health effectively. This may be an important reason for the influence of QoL on PF in the mediation path of this study.

PCDEA impacted adolescents’ PF through a chain mediating pathway involving SA and QoL. Adolescents spend a significant portion of their time at school, school is the most important place for their social interaction, and adapting to school is foundational for the health development of adolescents [23]. School maladaptation directly diminishes adolescents’ sense of belonging [28], reduces opportunities for social interaction, thereby impairing their QoL. The psychosocial development theory [66] emphasizes individuals’ experiences of identity exploration and crises at different stages. If adolescents encounter negative events in school, it may constitute a negative crisis in their psychosocial development stage. This crisis could impact their cognitive understanding of self and society, leading to persistent negative effects on individual psychosocial development, and even impeding adolescents’ enthusiasm for participating in other activities in their daily lives. For example, a negative experience in physical education class might serve as a hindrance to their active engagement in extracurricular sports activities. Consequently, school maladaptation can trigger negative emotions in adolescents, potentially reducing their satisfaction with the QoL.

Strengths and limitations

The advantages of this study are as follows: First of all, the utilization of a large sample obtained through sampling from 94 schools across nine districts in Shandong Province, enhancing the generalizability of the findings. Secondly, the results elucidate multiple indirect pathways through which PCDEA impact PF. This provides practical guidance for developing interventions and improving the PF of adolescents. Limitations of this study: Firstly, this study used a cross-sectional design and could not determine causality; Secondly, data collection for PCDEA, SA, and QoL relied on self-reports from participants, introducing the potential for subjectivity and recall bias.

Conclusion

The results of this study indicate that PCDEA did not have a direct effect on PF. However, they were found to influence adolescents’ PF through SA and QoL. Parents should aim to reduce the gap in academic aspirations with their children, thereby improving their SA and QoL, ultimately enhancing PF of adolescents. However, the more longitudinal studies are needed to confirm these findings and exploring the bidirectional relationship.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study will be available in the Database of Youth Health (DYH) in National Population Health Data Center. https://www.ncmi.cn/phda/dataDetails.do?id=CSTR:17970.11.A0031.202107.209.V1.0.

References

Masanovic B, Gardasevic J, Marques A, Peralta M, Demetriou Y, Sturm DJ, et al. Trends in physical fitness among school-aged children and adolescents: a systematic review. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:627529.

McGreevy KM, Radak Z, Torma F, Jokai M, Lu AT, Binder A, et al. DNAmFitAge: biological age indicator incorporating physical fitness. AGING-US. 2023;15:3904–38.

Soren H-L, Marie-Pierre Sylvestre A, Van Hulst TA, Barnett M-E, Mathieu M, Mesidor, et al. Estimating causal effects of physical activity and sedentary behaviours on the development of type 2 diabetes in at-risk children from childhood to late adolescence: an analysis of the QUALITY cohort. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2023;7:37–46.

Zaqout M, Michels N, Bammann K, Ahrens W, Sprengeler O, Molnar D, et al. Influence of physical fitness on cardio-metabolic risk factors in European children. The IDEFICS study. Int J Obes. 2016;40:1119–25.

Arrieta H, Rezola-Pardo C, Echeverria I, Iturburu M, Gil SM, Yanguas JJ, et al. Physical activity and fitness are associated with verbal memory, quality of life and depression among nursing home residents: preliminary data of a randomized controlled trial. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18:80.

Janssen A, Leahy AA, Diallo TMO, Smith JJ, Kennedy SG, Eather N et al. Cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular fitness and mental health in older adolescents: a multi-level cross-sectional analysis. Prev Med. 2020;132:105985

Lindgren C. Tracking opportunities and problems from infancy to adulthood; 20 years with the TOPP study. 2019.

Hamdani SMZH, Zhuang J, Hadier SG, Khurram H, Hamdani SDH, Danish SS, et al. Establishment of health related physical fitness evaluation system for school adolescents aged 12–16 in Pakistan: a cross-sectional study. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1212396.

Department of Physical Health and Art Education Ministry of Education. The eighth national student physique and health survey results released. Chin J School Health. 2021.

Santana CCD, de Barros MVG, de Medeiros FRC, Rangel JFLB Jr, Cantieri FP, Alarcon D, et al. Does physical fitness relate to academic achievement in high school students? J Phys Act Health. 2024;20:1018–26.

Hurtig-Wennlöf A, Ruiz JR, Harro M, Sjöström M. Cardiorespiratory fitness relates more strongly than physical activity to cardiovascular disease risk factors in healthy children and adolescents: the European youth heart study. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabilitation. 2007;14:575–81.

Petersen CB, Eriksen L, Dahl-Petersen IK, Aadahl M, Tolstrup JS. Self‐rated physical fitness and measured cardiorespiratory fitness, muscular strength, and body composition. Scandinavian Med Sci Sports. 2021;31:1086–95.

Cohen AK, Nussbaum J, Weintraub MLR, Nichols CR, Yen IH. Association of adult depression with educational attainment, aspirations, and expectations. Prev Chronic Dis. 2020;17:200098.

Schoon I, Burger K. Incongruence between parental and adolescent educational aspirations hinders academic attainment. Longitud Life Course Stud. 2022;13:575–95.

Burke PJ, Stets JE. Identity theory. Oxford University Press; 2009.

Guo X, Qin H, Jiang K, Luo L. Parent-child discrepancy in educational aspirations and depressive symptoms in early adolescence: a longitudinal study. J Youth Adolescence. 2022;51:1983–96.

Vrolijk P, Van Lissa CJ, Branje S, Keizer R. Longitudinal linkages between parent-child discrepancies in reports on parental autonomy support and informants’ depressive symptoms. J Youth Adolescence. 2023;52:899–912.

Douris PC, Hall CA, Jung M-K. The relationship between academic success and sleep, stress and quality of life during the first year of physical therapy school. J Am Coll Health. 2023;71:830–5.

Eoh Y, Lee E, Park SH. The relationship between children’s school adaptation, academic achievement, happiness, and problematic smartphone usage: a multiple informant moderated mediating model. Appl Res Qual Life. 2022;17:3579–93.

Merrell KW, Cedeno CJ, Johnson ER. The relationship between social behavior and self-concept in school settings. Psychol Schs. 1993;30:293–8.

Crowley SL, Merrell KW. The structure of the school social behavior scales: a confirmatory factor analysis. Assess Effective Intervention. 2003;28:41–55.

Hamwey M, Allen L, Hay M, Varpio L. Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological model of human development: applications for health professions education. Acad Med. 2019;94:1621–1621.

Bai M-Z, Yao S-J, Ma Q-S, Wang X-L, Liu C, Guo K-L. The relationship between physical exercise and school adaptation of junior students: a chain mediating model. Front Psychol. 2022;13:977663.

Yin H, Qian S, Huang F, Zeng H, Zhang CJP, Ming W-K. Parent-child attachment and social adaptation behavior in Chinese college students: the mediating role of school bonding. Front Psychol. 2021;12:711669.

Zhou X, Zhen R, Wu X. Insecure attachment to parents and PTSD among adolescents: the roles of parent–child communication, perceived parental depression, and intrusive rumination. Dev Psychopathol. 2021;33:1290–9.

Jackson SL, Cunningham SA. Social competence and obesity in elementary school. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:153–8.

Williams JW, Canterford L, Toumbourou JW, Patton GC, Catalano RF. Social development measures associated with problem behaviours and weight status in Australian adolescents. Prev Sci. 2015;16:822–31.

Renick J, Reich M. Best friends, bad food, and bullying: how students’ school perceptions relate to sense of school belonging. J Community Psychol. 2021;49:447–67.

Langberg JM, Dvorsky MR, Becker SP, Molitor SJ. School maladjustment and external locus of control predict the daytime sleepiness of college students with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2016;20:792–801.

Macdonald-Wallis K, Jago R, Page AS, Brockman R, Thompson JL. School-based friendship networks and children’s physical activity: a spatial analytical approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:6–12.

Saxena S, Orley J, WHOQOL Group. Quality of life assessment: the World Health Organization perspective. Eur Psychiatr. 1997;12:s263–6.

Lo HH-M. Quality of life among adolescents in Hong Kong: general and gender-specific effects of self-efficacy and mindfulness: a special issue on quality of life in Chinese societies in applied research in quality of life. Appl Res Qual Life. 2021;16:2311–34.

Jozefiak T, Wallander JL. Perceived family functioning, adolescent psychopathology and quality of life in the general population: a 6-month follow-up study. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:959–67.

Delgado-Floody P, Gómez-López M, Caamaño-Navarrete F, Valdés-Badilla P, Jerez-Mayorga D. The mediating role of the muscle quality index in the relation of screen time and abdominal obesity with health-related quality of life in Chilean schoolchildren. Nutrients. 2023;15:714.

Leibinger E, Åvitsland A, Resaland GK, Solberg RB, Kolle E, Dyrstad SM. Relationship between health-related quality of life and physical fitness in Norwegian adolescents. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:1133–41.

Evaristo S, Moreira C, Lopes L, Oliveira A, Abreu S, Agostinis-Sobrinho C, et al. Muscular fitness and cardiorespiratory fitness are associated with health-related quality of life: results from labmed physical activity study. J Exerc Sci Fit. 2019;17:55–61.

Da Costa B, Da Costa RM, De Mello GT, Bandeira AS, Chaput J-P, Silva KS. Independent and joint associations of cardiorespiratory fitness and weight status with health-related quality of life among Brazilian adolescents. Qual Life Res. 2023;32:2089–98.

Jarrin DC, Abu Awad Y, Rowe H, Noel NAO, Ramil J, McGrath JJ. Parental expectations are associated with children’s sleep duration and sleep hygiene habits. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2020;41:550–8.

Almroth M, László KD, Kosidou K, Galanti MR. Academic expectations and mental health in adolescence: a longitudinal study involving parents’ and their children’s perspectives. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64:783–9.

Guo J, Marsh HW, Parker PD, Morin AJS, Yeung AS. Expectancy-value in mathematics, gender and socioeconomic background as predictors of achievement and aspirations: a multi-cohort study. Learn Individual Differences. 2015;37:161–8.

Busing K, West C. Determining the relationship between physical fitness, gender, and life satisfaction. SAGE Open. 2016;6:215824401666997.

Rodrigues LP, Lima RF, Silva AF, Clemente FM, Camões M, Nikolaidis PT, et al. Physical fitness and somatic characteristics of the only child. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:324.

Tu S. Search of the ‘best’ option: American private secondary education for upper-middle-class Chinese teenagers. Curr Sociol. 2022;70:824–42.

Chen X, Allen JL, Hesketh T. The influence of individual, peer, and family factors on the educational aspirations of adolescents in rural China. Soc Psychol Educ. 2023;26:735–59.

Yi X, Fu Y, Burns RD, Bai Y, Zhang P. Body mass index and physical fitness among Chinese adolescents from Shandong Province: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:81.

Kumari R, Nath B, Singh Y, Mallick R. Health-related physical fitness, physical activity and its correlates among school going adolescents in hilly state in north India: a cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:401.

Sun J, Ban Y, Liu J. Relationship between bullying victimization and suicide ideation among Chinese adolescents: a moderated chain mediation model. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2024;156:107304.

Griffiths S, Murray SB, Bentley C, Gratwick-Sarll K, Harrison C, Mond JM. Sex differences in quality of life impairment associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61:77–82.

National Population Health Data Center. Database of youth health. 2021.

Shengfa Z, Wei L, Xiaosheng D, Wenxin C, Xiangren Y, Wei Z, et al. A dataset on the status quo of health and health-related behaviors of Chinese youth: a longitudinal large-scale survey in the secondary school students of Shandong Province. Chin Med Sci J. 2022;37:60.

Wang Y, Benner AD. Parent–child discrepancies in educational expectations: differential effects of actual versus perceived discrepancies. Child Dev. 2014;85:891–900.

Yi X, Fu Y, Burns R, Ding M. Weight status, physical fitness, and health-related quality of life among Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional study. IJERPH. 2019;16:2271.

Kowalski KC, Crocker PRE, Faulkner RA. Validation of the physical activity questionnaire for older children. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 1997;9:174–86.

Kent C, Kowalski, Peter RE, Crocker, Rachel M, Donen. The physical activity questionnaire for older children (PAQ-C) and adolescents (PAQ-A) manual. 2004.

Wu HR, Liu PL, Meng H. Norm, reliability and validity of children and adolescents’ QOL scale. Chin J School Health. 2006;(01):18–21.

Kim Y, Richards JS, Oldehinkel AJ. Self-control, mental health problems, and family functioning in adolescence and young adulthood: between-person differences and within-person effects. J Youth Adolescence. 2022;51:1181–95.

Moed A. An emotion-focused extension of coercion theory: emerging evidence and conceptualizations for parental experienced emotion as a mechanism of reinforcement in coercive parent–child interactions. Child Dev Perspect. 2024;18:82–7.

Li SD, Xia Y, Xiong R, Li J, Chen Y. Coercive parenting and adolescent developmental outcomes: the moderating effects of empathic concern and perception of social rejection. IJERPH. 2020;17:3538.

Feldman R, Masalha S, Derdikman-Eiron R. Conflict resolution in the parent–child, marital, and peer contexts and children’s aggression in the peer group: a process-oriented cultural perspective. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:310–25.

Oppong Asante K, Onyeaka HK, Kugbey N, Quarshie EN-B. Self-reported injuries and correlates among school-going adolescents in three countries in western sub-saharan Africa. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:899.

Van Loon AWG, Creemers HE, Okorn A, Vogelaar S, Miers AC, Saab N, et al. The effects of school-based interventions on physiological stress in adolescents: a meta‐analysis. Stress Health. 2022;38:187–209.

Legate N, Weinstein N, Przybylski AK. Parenting strategies and adolescents’ cyberbullying behaviors: evidence from a preregistered study of parent–child dyads. J Youth Adolescence. 2019;48:399–409.

Vrolijk P, Van Lissa CJ, Branje SJT, Meeus WHJ, Keizer R. Longitudinal linkages between father and mother autonomy support and adolescent problem behaviors: between-family differences and within-family effects. J Youth Adolescence. 2020;49:2372–87.

Shen B, Luo X, Bo J, Garn A, Kulik N. College women’s physical activity, health-related quality of life, and physical fitness: a self-determination perspective. Psychol Health Med. 2019;24:1047–54.

Cavalcanti LMLG, Lima RA, Silva CRDM, Barros MVGD, Soares FC. Constructs of poor sleep quality in adolescents: associated factors. Cad Saúde Pública. 2021;37:e00207420.

Erikson EH. Identity: youth and crisis. New York: NY: WW Norton; 1968.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate all adolescents, their parents and teachers who participated in this study voluntarily.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Population Health Data Center, NCMI202308GDN.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. HZ, CGG, BW and RZ performed material preparation and data collection. HZ, LYZ, YKY and YG cleaned and analyzed the data. HZ wrote the first draft of the manuscript. BW, CGG, XSD, RZ revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study involves human participants and was approved by Ethics Committee of Shandong University (20180517). The protocol has been performed with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1989 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Written informed consent to participate in this study was provided by the participants and their parents and/or legal guardians.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeng, H., Wang, B., Zhang, R. et al. Association of parent-child discrepancies in educational aspirations with physical fitness, quality of life and school adaptation among adolescents: a multiple mediation model. BMC Public Health 24, 2135 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19674-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19674-5