Abstract

Introduction

Scabies is a widespread issue in prisons due to overcrowded living conditions and limited healthcare resources. A recent study published in the Journal of Infection and Public Health discovered that the prevalence of scabies varies greatly among prisoners in different regions and facilities. This review aimed to determine the global prevalence and predictors of scabies among prisoners by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis.

Methods

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis checklist to report the findings of our systematic review and meta-analysis. Relevant databases including PubMed, Cochrane Library, ScienceDirect, and other grey literature databases were used to search and retrieve articles. The study included both published and unpublished research written in English languages for studies reporting the prevalence of human scabies among prisoners. This review has been registered on PROSPERO. The heterogeneity of the data was evaluated using the I2 statistic. A meta-analysis was conducted using STATA 17 software, with a 95% confidence interval. The researchers also conducted publication bias and sensitivity analysis.

Results

The review included 7 studies involving 1, 309,323 prisoners. All included studies involved cross-sectional study design. The prevalence of scabies among prisoners ranges from 0.72% in Italy to 41.01% in Cameroon. The global pooled prevalence of human scabies among prisoners was found to be 6.57% (95% CI; 2.16–19.94). According to subgroup analysis, the overall prevalence of scabies among African prisoners was 19.55% (95% CI; 9.44–40.45), while the prevalence among prisoners outside of Africa was 1.57% (95% CI; 0.77–3.19). The length of time spent in prison, sharing of clothing or beds, and hygiene practices were found to be factors that were significantly associated with the likelihood of prisoners developing human scabies.

Conclusion

The overall prevalence of human scabies is high among prisoners worldwide. Prisoners who spent more time in prison shared clothing or beds, and had poor hygiene practices were more likely to develop human scabies. Thus, efforts should be made by policymakers and program administrators to decrease the prevalence of scabies in prisons. The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis was registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews with registration number CRD42024516064.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sarcoptes scabiei, formerly known as Acarus scabiei, was originally classified under the genus Acarus. It was later reclassified under the genus Sarcoptes, which is part of the superfamily Sarcoptoidea and the family Sarcoptidae [1]. Different types of S. scabiei mites can infect various animals, including humans, dogs, rabbits, and red foxes [2]. Human scabies is an ectoparasitic infestation caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabies var. hominis which is an obligate parasite that completes its entire life cycle on humans. Female mites burrow into the skin and lay eggs, eventually triggering a host immune response that leads to intense itching and rash [3, 4]. These mites can survive for up to 24–36 h at temperatures of 21 °C and humidity levels of 40–80%, and can still infect others during this time [5]. These mites can remain contagious for up to a week at lower temperatures and higher humidity and can enter the skin when the temperature is above 20 °C [6]. Scabies are more likely to spread in environments where there is prolonged direct contact and overcrowding, such as prisons, military camps, and boarding schools [7, 8].

Different regions and countries have different standards for the amount of space allocated per person in prison cells, with Europe requiring 4 square meters per person, and Australia and New Zealand requiring 5.75 square meters per person. For single cells, the range of space recommendations is from 2.4 square meters in Korea to 16 square meters in Switzerland, while for multiple-occupancy cells, the range is from 1.25 square meters in Pakistan to 10 square meters in the Netherlands. Moreover, prison cell sizes in African countries vary, with Kenya having 3.7 square meters for double cells, Senegal with 3.55 square meters, Guinea with 2 square meters, Malawi with 2–4 square meters, Mauritius with 4.08 square meters, and South Africa with 5.5 square meters for single cells and 3.5 square meters for multiple cells [9].

The Global Prison Trends 2023 report by Non-Governmental Organization Penal Reform International reveals that the global prison population has reached a record high of 11.5 million, leading to overcrowding in approximately 120 countries [10]. Africa is particularly affected, with countries like the Republic of Congo experiencing overcrowding levels of over 600%. Other countries facing high occupancy rates include Haiti (401%), Uganda (374%), France (119%), the Philippines (375%), and Cambodia (350%) [10]. The number of women and girls in prison has also significantly increased, with a nearly 60% rise from 2000 to 2022, totaling over 740,000 individuals [10]. Studies have shown that the prison population, which is predominantly made up of young people and adults, is more likely to experience skin problems due to overcrowding and poor hygiene in prisons. Prisons are a potential reservoir for various skin diseases, particularly scabies. These may spread to the community through visitors, workers, or the released inmates [11, 12]. It can affect individuals from various socio-economic backgrounds, regardless of age, gender, or race [5]. Scabies can also be transmitted indirectly through objects like bedding, towels, and clothing [13]. Outbreaks frequently occur in institutions and enclosed communities like prisons, regardless of their income level [14]. These outbreaks can have significant health and economic consequences and are challenging to manage, especially in crowded settings [14].

Scabies symptoms typically appear 4–6 weeks after being infested, although sometimes there may be visible signs before symptoms manifest [15]. The main feature of scabies is generalized itching that is more intense during nighttime, which may lead to absenteeism from work, and sleep disturbance that affects the quality of life and causes stigma [16, 17]. A diagnosis of scabies can be confirmed, clinical, or suspected, but clinical or suspected diagnoses should only be made if other possible conditions are ruled out [18]. A confirmed diagnosis of scabies can be made by identifying the scabies mite, eggs, or fecal pellets through microscopic examination of skin samples, high-magnification devices, or dermoscopy [18, 19]. Moreover, clinical scabies can be diagnosed if at least one of the following criteria is present: scabies burrows, typical lesions on the male genitalia, typical lesions in a typical distribution, and two relevant history features [18]. Scabies are suspected if a person has typical lesions in a typical distribution along with one history feature, or if they have atypical lesions or distribution along with two history features. The history features include itching or a positive contact history [18]. Scabies lesions are typically found on the skin below the mid-upper arm and thigh in older children and adults, as well as in the groin, breast, and peri-umbilical areas. The hands, fingers, and wrists are common areas for lesions, while infants may have lesions on the trunk, scalp, palms, and soles [18].

In individuals with weakened immune systems, scabies can develop into a severe form known as crusted scabies, which is caused by an excessive infestation of the same mite responsible for scabies [20]. Scabies infestations typically involve 5 to 15 mites, but individuals with crusted scabies can have thousands to millions of mites [5], making them highly contagious and able to cause outbreaks. Crusted scabies can range from mild to severe [5, 21, 22] and can lead to bacterial infections, which can cause serious health issues such as glomerulonephritis, rheumatic heart disease, sepsis, and even death, due to the openings in the skin [23].

The primary recommended treatment for scabies is a topical medication, usually permethrin 5% cream or benzyl benzoate 25% lotion [7, 8, 24]. Ivermectin, which is taken orally, is recommended as a secondary option for treatment [25]. Scabies are a common infectious disease that can be easily treated with a scabicide such as 5% permethrin [8, 24]. It is crucial to also provide treatment for anyone who has come into contact with the infected patient and to properly clean clothing and furniture to prevent the spread of infection [26].

Scabies is a widespread neglected tropical disease, with approximately 450 million new cases each year worldwide [3, 27, 28]. While scabies is more common in developing countries [7, 29], outbreaks in developed countries also contribute significantly to the global burden of the disease [30]. The prevalence of scabies varies widely, with the highest prevalence recorded in Papua New Guinea (71%), Panama (32%), and Fiji (32%), according to a global systematic analysis of population-based surveys [27]. In developed countries, the prevalence of scabies was typically substantially lower, with very few estimates above 2–4% [27, 31, 32]. Moreover, a previous worldwide systematic review which was conducted in 2022 found that the occurrence of scabies varies, with rates as low as 0.18% in Uganda and as high as 76.9% in Indonesia [33]. Another systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that the pooled global prevalence of scabies was 14.0% [34]. It was also found that the prevalence of scabies among prisoners differs greatly among different countries. It ranges from 0.72% in Italy [35] to 41.1% in Cameroon [36]. Scabies was recently recognized by the WHO as an Neglected Tropical Disease and included as part of the WHO roadmap for Neglected Tropical Disease 2021–2030 [37]. Although there are effective treatments for scabies [38], preventing and controlling the spread of the infestation in the population is difficult due to frequent re-infestation through community and personal interactions [7]. Besides the World Health Organization (WHO), the International Alliance for the Control of Scabies (IACS) [18] and informal research groups like the Sarcoptic-World Molecular Network are dedicated to collaborating towards the worldwide eradication of scabies [39]. Scabies is often overlooked in health control programs and research, despite its high prevalence [40].

Previous studies on human scabies in prisoners have yielded inconsistent results worldwide. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to determine the overall prevalence of human scabies among prisoners globally, as it is a significant issue in many prisons. Understanding this prevalence can help inform strategies for controlling and reducing the burden of scabies in prison populations. Policymakers and program implementers need to understand the prevalence of scabies in these settings to implement effective strategies for prevention and control. This study is the first of its kind to systematically review and analyze the prevalence of scabies among prisoners globally.

Methods and materials

Search strategy

A search strategy was implemented using electronic databases (PubMed, Science Direct, Cochrane Library, Google Scholar, and Grey Literature) which were systematically searched online to retrieve related articles using keywords. A comprehensive database search was performed using the Boolean operators “OR”, “AND”, and keywords. The literature search technique was conducted by using the keywords (“prevalence” OR “magnitude’’ OR “burden” OR “epidemiology” OR “predictor” OR “determinants” OR “associated factors” OR “factors” OR “causes”) AND (“human scabies” OR “scabies” OR “Sarcoptes scabiei” OR “skin disease” OR “skin infection” OR “dermatosis” OR “ectoparasite”) AND (“penitentiary” OR “prison” OR “prisoner” OR “prisoners” OR “imprisonment” OR “jail” OR “criminals” OR “convicts” OR “confined area” OR “inmates” OR “detainees” OR “offenders” OR “incarcerated” OR “detention”). We searched all articles, whether they were published or unpublished, until March 17, 2024. Grey literature was searched in institutional repositories and ResearchGate. The search was conducted using search terms related to the prevalence of human scabies among prisoners. Searches were conducted from March 1, 2024, to March 17, 2024. All original articles concerning human scabies among prisoners were reviewed for eligible studies. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis(PRISMA) checklist to present the results of our systematic review and meta-analysis [41]. This systematic review and meta-analysis were performed by following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [42]. The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis is registered in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and obtained a registration number CRD42024516064.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All English-language, full-text, original research articles and doctoral dissertations with observational study design (cross-sectional, case-control, or cohort study design) conducted among prisoners with no limit to certain geographical areas with adults, children, or adolescents, that were published in peer-reviewed journals or filed as completed dissertations until March 17, 2024, were eligible for inclusion. In contrast, qualitative studies, surveys, editorials, reports, and studies in which their prevalence was computed among those patients who had skin lesions were excluded from this study.

Data extraction

After searching in relevant databases, articles was imported into Endnote version 20 and duplicates were removed. After initial screening, three reviewers (AMD, EKB, and TFA) downloaded abstracts to assess them for inclusion. If reviewers disagreed about whether a search result was relevant to the study, it was included for retrieval. Additionally, the abstracts’ compliance with the inclusion criteria was evaluated. At this stage, articles considered irrelevant or out of the scope of the study were excluded and the full text of the remainder was downloaded for a detailed review. In this review, if the reviewers were unsure about including or excluding an article based on the abstract, another author would decide. However, there were no disagreements or uncertainties between reviewers in this particular review regarding the inclusion or exclusion of articles based on their abstracts.

Data quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist was used to assess the quality of the studies. Using this tool as a protocol, four reviewers (AMD, MGT, and ETF, ) then assessed the quality of potentially eligible articles using the Joana Briggs Institute (JBI) criteria. Papers are screened for inclusion based on title, abstract, and other relevant information and then undergo a thorough evaluation before being included in the final review. The average of those independent reviewers’ scores was used to determine whether the articles should be included. Discrepancies in quality assessment scores were resolved with a third reviewer (OA), whenever appropriate. Those studies with scores of 5 or more in JBI criteria were considered to have good quality and were included in the review [43]. The study’s researchers attempted to get in touch with the authors of the articles twice in case more information was required, such as when patient outcome statistics were lacking (Table 1).

Data analysis

Information on the study characteristics (Name of author/s, publication year, study location, study design, sample size, prevalence, and significant factors associated with scabies) was extracted from each study using Microsoft Excel Version 2019 and the extracted data were exported to STATA version 17 software for analysis. Data were summarized by tables and forest plots. The standard error and 95% confidence interval for the prevalence of scabies patients were calculated for those studies in which estimates of standard error and 95% confidence interval for their proportion were not found in the full text of the article. The statistical heterogeneity was checked subjectively by using forest plots, and objectively by Cochrane Q-test and I2 statistics [49]. A meta-analysis based on a random effect model was applied to determine the pooled prevalence of human scabies infection in prison because significant and considerable heterogeneity exists between studies (I2 = 99.78%, Q = 390.33, p < 0.001). The presence of publication bias was checked by using a funnel plot and Egger’s and Begg’s statistical tests [50]. In this study, Egger’s and Begg’s tests at a 5% significant level were not significant for publication bias. However, the Doi plot revealed major asymmetry with an LFK index of 8.92, indicating the presence of publication bias. Subgroup analysis was also conducted based on the study setting.

Result

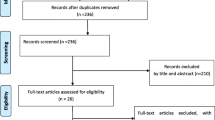

A total of 1479 records were identified through our initial database search. After duplicate records were removed, 1355 records were reviewed by title and abstract. Fifty-six articles were included for full-text review. After applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of seven studies were finally included in the review (Fig. 1). No additional studies were obtained after retrieving the references of the 7 included articles.

Study characteristics

A meta-analysis was conducted on seven studies published between 2014 and 2023. These studies were carried out in various countries, including Cameroon [36], Poland [45], Ethiopia [46], Iran [47], Italy [35], Hungary [51], and Niger [48]. All of the studies were cross-sectional [35, 36, 45,46,47,48, 51]. The total sample size for this review was 1,309,323 with a maximum sample size of 1,302,481 in Poland [45], and a minimum sample of 217 in Cameroon [36]. The highest occurrence of scabies infestation was found in Cameroon at a prevalence rate of 41% [36], while the lowest occurrence was in Italy at a rate of 0.72% [35] (Table 2).

Overall prevalence of scabies among prisoners

From the included studies in this systematic review, the lowest prevalence (0.72%) was found in a study conducted in Italy [35] whereas the highest prevalence of scabies (41.01%) was found in a study conducted in Cameroon [44]. In this review, the pooled prevalence of scabies among prisoners were found to be 6.57% (95% CI; 2.16–19.94) (Fig. 2).

Subgroup analysis based on study area

By considering the heterogeneity of included studies in our meta-analysis, we conducted subgroup group analysis based on the study setting. According to subgroup analysis, the overall prevalence of scabies among African prisoners was 19.55% (95% CI; 9.44–40.45), while the prevalence among prisoners outside of Africa was 1.57% (95% CI; 0.77–3.19) (Fig. 3).

Predictors of scabies among prisoners

A study conducted in Ethiopia [46] found that the length of time spent in prison is significantly associated with the occurrence of scabies. Prisoners who had been in prison for less than two months were 4.53 times [AOR: 4.53 (95% CI 1.51, 13.54)] more likely to develop scabies compared to those who had been there longer. Similar findings were observed in studies conducted in Iran [47] and Niger [48]. Based on a study conducted in Italy [35] also showed that there was a statistically significant association between the length of time spent in prison and the occurrence of human scabies.

This systematic review also found that hygienic practices were significantly associated with the occurrence of scabies among prisoners, based on included studies [44, 46, 48]. Based on a study conducted in Ethiopia [46], prisoners who did not use soap during hand washing had 5.53 times [AOR = 5.53; 95% CI: 1.45–21.17] higher odds of exhibiting scabies. A study conducted in Cameroon [44] also found that not bathing daily was associated with 1.23 times [AOR = 1.23; 95% CI: 2.10, 60.06] higher likelihood of developing scabies, while not doing laundry weekly was associated with 16.27 times [AOR = 16.27; 95% CI: 4.21, 62.84] higher likelihood. A study conducted in Niger [48] also found there was a significant association between hygiene factors, like toilet usage and soap usage, and the presence of scabies.

Sharing clothes or bedding with other inmates was also found to be significantly associated with scabies occurrence in studies conducted in Cameroon [36] and Ethiopia [46]. In Cameroon [36], inmates who shared clothes or bedding with other prisoners were 2.71 times [AOR = 2.71; 95% CI: 1.81, 4.06] more likely to develop scabies compared to those who did not share these items. Moreover, a study in Ethiopia [46] found that prisoners who did share clothes were 3.81 times [AOR = 3.81; 95% CI (1.09, 13.29)] more likely to develop scabies compared to those who did not share clothes.

Based on included studies [36, 47], overcrowding in prisons was found to be significantly associated with scabies, with a higher number of detainees per cell increasing the likelihood of scabies. A study in Cameroon [36] revealed that prisoners who had more than 10 people in their cell were 1.89 times [AOR = 1.89; 95% CI: 1.25–2.84] more likely to have scabies compared to prisoners with fewer people in their cell. A study conducted in Iran [47] revealed a statistically significant association between the number of roommates and the likelihood of experiencing scabies.

Publication bias assessment

The researchers checked for publication bias by visually inspecting a funnel plot, as well as using statistical tests. The funnel plot showed that the included studies were distributed asymmetrically. However, both Begg’s and Egger’s tests indicated the absence of publication bias in the global pooled prevalence of human scabies among prisoners. The tests showed no statistical evidence of publication bias with a p-value greater than 0.05 (P value; Eggers test = 0.21, Beggs test = 0.23), and the funnel plot was asymmetrical (Fig. 4). Funnel plots, Egger’s, and Begg’s tests are ineffective in detecting publication bias in a meta-analysis of proportions. Instead, Doi plots and the LFK index are suggested as better alternatives [52]. Accordingly, the Doi plot revealed a major asymmetry (LFK index = 8.92), indicating the presence of publication bias in the data (Fig. 5). Thus, it is crucial to be careful when interpreting the results of this systematic review and meta-analysis to account for the possibility of publication bias.

Sensitivity analysis

The result of sensitivity analyses revealed that none of the studies included influenced the overall estimate (Fig. 6).

Discussion

Although the WHO guideline recommends people who are in prison have the same right to health care as everyone else, the majority of prisoners in several countries have challenges easily accessing health services as compared to the community [53]. Many people come into prison with medical and mental health problems that, if left untreated, can spread within the prison and be carried back into the community upon their release [54].

This systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that the pooled global prevalence of human scabies among prisoners was found to be 6.57% (95% CI; 2.16–19.94). These findings might be due to the persistent overcrowding of prisons found all around the globe, leading to an increase in the number of prisoners per cell. Inmates being in physical contact with each other in cells (e.g., at meals, on walks, and at work in the prison) and with prison Staff, medical personnel, or visitors [55].This finding align with another systematic review and meta-analysis that looked at scabies prevalence in the general population, which found that 14% of people worldwide have scabies [34]. Based on subgroup analysis, the pooled prevalence of scabies among African prisoners was found to be 19.55% (95% CI; 9.44–40.45), while among prisoners outside of Africa, it was 1.57% (95% CI; 0.77–3.19). A subgroup analysis found a higher prevalence of scabies in African prisons compared to countries outside of Africa, likely due to poor hygiene and conditions in African detention centers [56]. This finding was also supported by previous global systematic reviews that found that the prevalence of scabies varied widely, but was generally higher than 10% in all regions except Europe and the Middle East [27, 33]. This variation in scabies prevalence could be attributed to factors such as the sociodemographic and behavioural traits of the individuals being studied, as well as the specific settings in which the research was conducted. Due to a limited number of studies from tropical countries being included in our review, and considering that scabies infections are more prevalent in tropical and impoverished regions with limited access to water, where overcrowding and high temperatures promote the spread of the scabies mite [7, 27], the actual prevalence of scabies among prisoners may be higher than reported.

This systematic review examined various factors associated with the likelihood of scabies among prisoners. The analysis found that the amount of time spent in prison, hygiene practices, sharing of clothes or bedding, and overcrowding in prison cells were all significant predictors of scabies among prisoners. Accordingly, prisoners who had been in prison for less than two months were five times [AOR: 4.53 (95% CI 1.51, 13.54)] more likely to develop scabies compared to those who had been there longer. The possible justification for this could be that prisoners who are relatively new to the prison environment may be more prone to contracting scabies and prisoners who have been incarcerated for a longer period may have built up immunity to the infestation.

Prisoners who did not practice good hygiene, such as not using soap when washing their hands or not bathing daily, were more likely to get scabies. Similar findings were also found in Nigeria [57] which showed the frequency of baths and frequency of soap usage were significantly associated with the presence or absence of scabies. If people in prisons don’t practice good hygiene, like bathing regularly, using soap while washing hands, and cleaning their clothes, the chances of scabies spreading can be increased. This is because prisons have crowded living conditions, which makes it easier for scabies mites to pass from one person to another through close contact.

Sharing clothes or beddings with other inmates was also found to be significantly associated with scabies occurrence. This can significantly increase the likelihood of scabies occurrence primarily transmitted through direct skin-to-skin contact with an infected individual. Sharing clothes or beddings increases the opportunities for this type of contact, allowing scabies mites to transfer from one person to another. The act of inmates sharing clothes or beddings can lead to the easy spread of scabies in prison. These findings were supported by a study conducted in Ethiopia [58]. A previous review conducted globally also revealed that scabies can be transmitted through beddings, towels, and clothing [13].

The review concluded that prisoners in overcrowded cells are at a higher risk of contracting scabies compared to those in less crowded cells. The close physical proximity of inmates in crowded spaces facilitates the spread of scabies mites through physical contact, making overcrowded environments more conducive to the transmission of the skin condition. This finding is also supported by previous studies conducted in the Fuji trial [59]. It was also found that scabies was significantly associated with poverty and overcrowding [7, 8].

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study was the first to investigate the worldwide prevalence of scabies among prisoners and its contributing factors, but this review only looked at those articles published in the English language. Besides, the results obtained from our systematic review and meta-analysis may not be fully representative on a global scale, as the included studies were limited to only six countries.

Conclusion and recommendations

The overall prevalence of scabies among prisoners was found to be high globally. Factors such as the length of time spent in prison, sharing of clothing or beddings, personal hygiene habits, and overcrowding were identified as associated factors for scabies occurrence among prisoners. Efforts to reduce this risk involve encouraging good personal hygiene habits, ensuring inmates have access to clean clothes and beddings, establishing effective laundry procedures, and educating people about the significance of not sharing personal belongings. Taking measures to alleviate overcrowding is also crucial for reducing the prevalence and transmission of scabies among incarcerated individuals. The WHO and the International Committee of the Red Cross focus on healthcare in prisons and should prioritize implementing effective prevention and control measures to control and eliminate scabies.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis

- WHO:

-

World health organization

References

Arlian LG, Morgan MS. A review of Sarcoptes scabiei: past, present and future. Parasites Vectors. 2017;10:1–22.

Schoch CL, Ciufo S, Domrachev M, Hotton CL, Kannan S, Khovanskaya R, et al. NCBI Taxonomy: a comprehensive update on curation, resources and tools. Database. 2020;2020:baaa062.

Engelman D, Cantey PT, Marks M, Solomon AW, Chang AY, Chosidow O, et al. The public health control of scabies: priorities for research and action. Lancet. 2019;394(10192):81–92.

Engelman D, Steer AC. Control strategies for scabies. Trop Med Infect Disease. 2018;3(3):98.

Heukelbach J, Feldmeier H, Scabies. Lancet. 2006;367(9524):1767–74.

Arlian L, Rapp C, Vyszenskimoher D, Morgan M. Sarcoptes scabiei: histopathological changes associated with acquisition and expression of host immunity to scabies. Exp Parasitol. 1994;78(1):51–63.

Hay R, Steer A, Engelman D, Walton S. Scabies in the developing world–-its prevalence, complications, and management. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18(4):313–23.

Idriss S, Levitt J. Malathion for head lice and scabies: treatment and safety considerations. J Drugs Dermatology: JDD. 2009;8(8):715–20.

Dahiya S, Simpson PL, Butler T. Rethinking standards on prison cell size in a (post) pandemic world: a scoping review. BMJ open. 2023;13(4):e069952.

https://www.penalreform.org/global-prison-trends-2023/imprisonment-and-prison-overcrowding/. Penal Reform International; 2023.

Chimphambano C, Komolafe I, Muula A. Prevalence of HIV, HepBsAg and Hep C antibodies among inmates in Chichiri Prison, Blantyre, Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2007;19(3):104–6.

Kazi AM, Shah SA, Jenkins CA, Shepherd BE, Vermund SH. Risk factors and prevalence of tuberculosis, human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus among prisoners in Pakistan. Int J Infect Dis. 2010;14:e60–6.

Walton SF, Currie BJ. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(2):268–79.

Cassell JA, Middleton J, Nalabanda A, Lanza S, Head MG, Bostock J, et al. Scabies outbreaks in ten care homes for elderly people: a prospective study of clinical features, epidemiology, and treatment outcomes. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(8):894–902.

WHO. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/scabies. 2023.

Swe P, Reynolds S, Fischer K. Parasitic scabies mites and associated bacteria joining forces against host complement defence. Parasite Immunol. 2014;36(11):585–93.

Jackson A, Heukelbach J, Filho AFS, Campelo Júnior EB, Feldmeier H. Clinical features and associated morbidity of scabies in a rural community in Alagoas, Brazil. Tropical Med Int Health. 2007;12(4):493–502.

Engelman D, Yoshizumi J, Hay R, Osti M, Micali G, Norton S, et al. The 2020 international alliance for the control of scabies consensus criteria for the diagnosis of scabies. Br J Dermatol. 2020;183(5):808–20.

Leung V, Miller M. Detection of scabies: a systematic review of diagnostic methods. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol. 2011;22:143–6.

Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Reviews. 2007(3).

Bouvresse S, Chosidow O. Scabies in healthcare settings. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23(2):111–8.

Strong M, Johnstone P. Interventions for treating scabies. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007(3):Cd000320.

Thornley S, Marshall R, Jarrett P, Sundborn G, Reynolds E, Schofield G. Scabies is strongly associated with acute rheumatic fever in a cohort study of Auckland children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;54(6):625–32.

Modamio P, Lastra CF, Sebarroja J, Mariño EL. Stability of 5% permethrin cream used for scabies treatment. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2009;28(7):668.

Organization WH. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. World Health Organization; 2019.

Sunderkötter C, Wohlrab J, Hamm H. Scabies: epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2021;118(41):695.

Romani L, Steer AC, Whitfeld MJ, Kaldor JM. Prevalence of scabies and impetigo worldwide: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15(8):960–7.

Lake SJ, Kaldor JM, Hardy M, Engelman D, Steer AC, Romani L. Mass drug administration for the control of scabies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;75(6):959–67.

Fuller LC. Epidemiology of scabies. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2013;26(2):123–6.

Engelman D, Kiang K, Chosidow O, McCarthy J, Fuller C, Lammie P, et al. Toward the global control of human scabies: introducing the International Alliance for the Control of Scabies. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(8):e2167.

Zhang W, Zhang Y, Luo L, Huang W, Shen X, Dong X, et al. Trends in prevalence and incidence of scabies from 1990 to 2017: findings from the global Burden of disease study 2017. Emerg Microbes Infections. 2020;9(1):813–6.

Bowen AC, Mahe A, Hay RJ, Andrews RM, Steer AC, Tong SY, et al. The global epidemiology of impetigo: a systematic review of the population prevalence of impetigo and pyoderma. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136789.

Schneider S, Wu J, Tizek L, Ziehfreund S, Zink A. Prevalence of scabies worldwide—An updated systematic literature review in 2022. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2023;37(9):1749–57.

Gupta S, Thornley S, Morris A, Sundborn G, Grant C. Prevalence and determinants of scabies: a global systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2024:2024.05. 06.24306963.

Mannocci A, Di Thiene D, Semyonov L, Boccia A, La Torre G. A cross-sectional study on dermatological diseases among male prisoners in southern L azio, I taly. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53(5):586–92.

Kouotou EA, Nansseu JRN, Sangare A, Moguieu Bogne LL, Sieleunou I, Adegbidi H, et al. Burden of human scabies in sub-saharan African prisons: evidence from the west region of Cameroon. Australas J Dermatol. 2018;59(1):e6–10.

El-Moamly AA. Scabies as a part of the World Health Organization roadmap for neglected tropical diseases 2021–2030: what we know and what we need to do for global control. Trop Med Health. 2021;49(1):1–11.

Hay RJ, Asiedu K. Skin-related neglected tropical diseases (skin NTDs)—a new challenge. MDPI; 2018. p. 4.

Alasaad S, Walton S, Rossi L, Bornstein S, Abu-Madi M, Soriguer RC, et al. Sarcoptes-world molecular network (Sarcoptes-WMN): integrating research on scabies. Int J Infect Dis. 2011;15(5):e294–7.

Takano K, De Hayr L, Carver S, Harvey RJ, Mounsey KE. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic considerations for treating sarcoptic mange with cross-relevance to Australian wildlife. Int J Parasitology: Drugs Drug Resist. 2023;21:97–113.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;134:103–12.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med 2009.

Masresha SA, Alen GD, Kidie AA, Dessie AA, Dejene TMJSR. First line antiretroviral treatment failure and its association with drug substitution and sex among children in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. 2022;12(1):18294.

Kouotou E, Nansseu J, Kechia F, Sieleunou I, Apasew H, Prevalence. Drivers and clinical features of human Scabies at the Mfou principal Prison, Centre Region of Cameroon. J Clin Exp Dermatol Res. 2016;7(349):2.

Bartosik K, Tytuła A, Zając Z, Buczek W, Jasztal-Kniażuk A, Błaszkiewicz PS, et al. Scabies and pediculosis in penitentiary institutions in poland—A study of ectoparasitoses in confinement conditions. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(17):6086.

Bogino EA, Woldegeorgis BZ, Wondewosen L, Dessu BK, Obsa MS, Hanfore LK, et al. Scabies prevalence and its associated factors among prisoners in southern Ethiopia: an institution-based analytical cross-sectional study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17(12):e0011826.

RAHMATI RM, Malekzad F, RAHMATI RS. Prevalence of scabies and pediculosis in Ghezel Hesar prison. 2007.

Harouna M, Mamadou AKI, Hamadou M, Ousmane S, Abdou KI, Ali I, PREVALENCE AND ASSOCIATED FACTORS OF HUMAN SCABIES IN PRISONS IN DOSSO, NIGER. Medecine tropicale et sante internationale. 2023;3(3):mtsi. v3i. 2023.398.

Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: cochrane book series. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: cochrane book series. 2008. John Wiley & Sons Location: Hoboken, New Jersy, USA; 2008.

Sterne JA, Egger MJJ. Funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. 2001;54(10):1046–55.

Vanya M, Szili K, Magori K, Krisztina V. Skin diseases and sexually transmitted infection in a Hungarian prison. Reviews Res Med Microbiol. 2017;28(3):95–6.

Furuya-Kanamori L, Barendregt JJ, Doi SA. A new improved graphical and quantitative method for detecting bias in meta-analysis. JBI Evid Implement. 2018;16(4):195–203.

Gatherer A. Health in prisons: a WHO guide to the essentials in prison health. WHO regional office Europe; 2007.

Redemske D. Providing healthcare in the prison environment. Omaha, NE: HDR; 2018.

Beaudry G, Zhong S, Whiting D, Javid B, Frater J, Fazel S. Managing outbreaks of highly contagious diseases in prisons: a systematic review. BMJ Global Health. 2020;5(11):e003201.

Van Hout M-C, Mhlanga-Gunda R. Prison health situation and health rights of young people incarcerated in sub-saharan African prisons and detention centres: a scoping review of extant literature. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2019;19:1–16.

Oninla OA, Onayemi O. Skin infections and infestations in prison inmates. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51(2):178–81.

Melese F, Malede A, Sisay T, Geremew A, Gebrehiwot M, Woretaw L, et al. Cloth sharing with a scabies case considerably explains human scabies among children in a low socioeconomic rural community of Ethiopia. Trop Med Health. 2023;51(1):52.

Romani L, Whitfeld MJ, Koroivueta J, Kama M, Wand H, Tikoduadua L, et al. The epidemiology of scabies and impetigo in relation to demographic and residential characteristics: baseline findings from the skin health intervention Fiji trial. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(3):845.

Funding

No specific funding was received for this research from any public, commercial, or not-for-profit organizations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AMD, EKB, AAT, TFA, OA, and MGT developed the protocol and were involved in the design, selection of the study, data extraction, and statistical analysis. The data quality assessment involved AMD, MGT, ETF, OA, AMD, and NK developing the initial drafts of the manuscript. Every author has reviewed and given their approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Delie, A.M., Bogale, E.K., Anagaw, T.F. et al. Global prevalence and predictors of scabies among prisoners: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 24, 1894 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19401-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-19401-0