Abstract

Background

Parental depression is a significant problem that negatively affects parents’ welfare and influences family dynamics, children’s academic and health behaviors, and mental health. However, there is limited evidence regarding the impact of the parental depression into the children’s’ psychological and physical wellbeing on Asian cultures. This study examined the psychological burdens and health behaviors of adolescent children with parents with depression in the Republic of Korea.

Methods

We conducted a cross-sectional study using data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) spanning 2013 to 2021 to compare health behaviors and mental health outcomes between 203 adolescent children with parents diagnosed with depression and 3,856 control adolescents aged 12–19 years.

Results

Following multivariate adjustments, the risk of depressive mood for more than two weeks was significantly increased in boys with parental depression (adjusted Odds Ratio [aOR] = 2.05, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 1.91–3.52) and adolescents with parents with moderate-to-severe depression (aOR = 2.60, 95% CI = 1.17–5.77). Adolescents with parental depression reported significantly worse subjective health status (aOR = 1.88, 95% CI = 1.05–3.36) and higher stress levels (aOR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.33–2.76). Additionally, when parental depression was present and the time since depression diagnosis was more than five years, adolescents with parental depression exhibited even poorer subjective health status and higher stress levels.

Conclusions

The study found that adolescents whose parents experienced depression had poorer mental health than those whose parents did not have mental health issues. These findings emphasize the importance of providing support for the mental health of adolescents in families affected by parental depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Depression is characterized by a persistently-low mood and an impairment of various aspects of one’s ability to function mentally — including thought content and process, sleep, concentration, energy levels, and physical activity [1]. The World Health Organization has reported that depression is gradually increasing worldwide and is expected to become the most burdensome disease across humanity by 2030 [2].

Parental depression is a significant problem that negatively affects parents’ welfare and influences family dynamics, children’s academic and health behaviors, and mental health. Studies have shown that parental depression increases stress in children [3], suicide rates [4], and depressive symptoms [5,6,7]. The severity and duration of parental depression, as well as its treatment status, may also affect children’s well-being [5, 8,9,10].

Adolescents are particularly vulnerable to the effects of parental depression [7]. This stage of life involves rapid physical and emotional development, and external factors such as changes in family structure, school stress, and peer relationships can contribute to emotional problems [11]. Therefore, depression in parents (who act as primary caregivers) affects parenting styles, family dynamics and emotional support, all of which can affect adolescent health [8, 11]. The chronicity of parental illness, family structure, income level, and other factors that affect family dynamics can also exacerbate the impact of parental depression on children [3, 12, 13].

Although studies on the physical and psychological well-being of children with parental depression have been conducted in Western countries [3, 5, 14], there is limited evidence regarding their impact on Asian cultures [15]. Specifically, parents in Asian countries exhibit higher parenting stress compared to Western parents [16]. The increasing prevalence of single-parent families in Asian countries, driven by rapid changes in family structure [17] and the burden of education expenses [18], contributes to the gradual rise in parental depression. Considering that East Asia exhibited the highest rates of parental depression compared that Europe showed the lowest rates [19], it becomes essential to explore how parental depression affects adolescnet children in Asian contries with reflecting the cultural context in Asia.

Korean adolescents already have the highest rates of suicide (23.6 per 100,000 population) and depressive mood among compared to other OECD countries [20,21,22]. In addition, through the COVID-19 pandemic period, physical activity of adolescents has been declining, and BMI is gradually increasing [23] even though there has been a decreasing trend in smoking and alcohol use among Korean adolescents’ health behaviors. These results highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between parental depression and the health and well-being of adolescent children is crucial for developing preventive strategies. Therefore, this study used data from the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) to investigate how parental depression affects the health behaviors and mental well-being of adolescent children.

Methods

Study design, settings and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study using data from the sixth (2013–2015), seventh (2016–2018), and eighth (2019–2021) waves of KNHANES [24]. The KNHANES is a nationwide survey that examines the nutritional and overall health statuses of the Korean population and provides comprehensive information on sociodemographic characteristics, health behaviors, and overall well-being. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB number E-2304-102-1425).

To account for family structure, the initial sample consisted of 4,695 adolescents (aged 12–19) from either single-parent or two-parent families who completed both the health examination and health interview surveys in three waves of KNHANES. From this initial group, 250 adolescents were excluded because their parents did not respond to questionnaires regarding depression and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Considering that chronic and severe parental illnesses can affect family dynamics and children’s health [25,26,27,28,29], we excluded 350 participants whose parents had a history of cardiovascular disease, renal failure, cirrhosis, or cancer. The final sample consisted of 4,059 adolescents (Fig. 1).

Associated factors

Adolescents’ variables

Participants’ demographic and socioeconomic characteristics — such as age, sex, education level, household income and family type — were obtained from the KNHANES surveys conducted between 2013 and 2021 [26, 30, 31] (Table 1). We selected participants’ weight for their age, smoking habits, alcohol consumption, and physical activity levels as health behavior factors for adolescents’s variables (Table 2). Three factors — subjective health status, stress levels, and depressive mood — were selected as the psychological well-being factors attributable to adolescents (Table 2).

For the health behaviors factors, participants’ weight for their age was classified into three groups (< 5th, 5th -95th, and ≥ 95th percentile) according to the Korean National Growth Chart in 2017 [32]. The KNHANES questionnaires on smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity levels were used to categorize the participants’ health behavior statuses. Participants were classified as “ever-smokers” or “never-smokers” based on smoking status (“yes” or “no”) for participants aged 12–18 years, and lifetime smoking status (less than 100 cigarettes, 100 or more cigarettes, or never) for participants aged 19 years or older. Lifetime alcohol consumption was determined by asking whether the participants had ever consumed more than one drink in their lives, with a “yes” or “no” answer. The researchers assessed participants’ annual physical activity levels by categorizing the data into binary variables. This categorization depended on whether the participants met the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM)’s exercise guidelines, which require at least 150 min per week of moderately-intensive physical activity, more than 75 min per week of vigorously-intensive physical activity, or a balanced combination of the two.

For the psychological well-being factors, the participants’ subjective health statuses were assessed using a single question: “How would you rate your general health?” The answers were divided into two groups: one group contained “very poor” or “poor” answers, with the other group containing “very good,” “good,” or “fair” answers. The adolescents’ stress levels were assessed by asking them about the amount of stress they experienced on a daily basis. Participants who answered “very high stress” or “high stress” were classified into the “high-stress” group, whereas those who answered with “very low stress” or “low stress” were classified into the “low-stress” group. Depressive mood was assessed using a single question: “In the past year, have you experienced a period of two weeks or longer when you felt sad or hopeless almost every day?”, with “yes” or “no” answers.

Parental depression variables

Information on the diagnosis, treatment, and current depression status of the parents was obtained using medical history questionnaires. Parents with depression were identified based on their response (yes or no) to the question regarding “diagnosis of depression by a doctor.”’ The current depression status of parents was determined by their response (yes or no) to the question about the “current presence of depression.” Additionally, confirmation of parents’ experience with depression treatment was based on their response (yes or no) to the question about “receiving treatment for depression.” To calculate the duration of parental depression, we subtracted the parents’ reported age at the first diagnosis of depression from their age at the time of the questionnaire.

The self-reported depression questionnaire did not include information on the severity of the depressive symptoms. Therefore, we used PHQ-9 scores to determine the severity of depressive symptoms among parents. The internal consistency of the Korean version PHQ-9 was assessed by using the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, and it was found to be 0.81 [33]. As the PHQ-9 scores were only collected in 2014, 2016, 2018, and 2020, we extracted a subpopulation of 1,714 participants who provided PHQ-9 scores from the final population. We categorized the severity of parental depression as follows: scores of 0–4 presented “none to minimal depression,” scores of 5–9 presented “mild depression,” and scores of 10 or more presented “moderate to severe depression.”

Data analysis

Descriptive statistical methods were used to provide an overview of the baseline characteristics of the study participants. Categorical variables were analyzed using the chi-squared test, whereas continuous variables were analyzed using the unpaired t-test. We performed univariate logistic regression analysis to assess the association between parental depression and adolescent factors such as heath behaviors factors (abnormal weight for age, smoking, alochol use, physical activity) and psychological factors (subjective health status, stress level, depressive mood). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, we included fourcovariates — sex of adolescent children, age of adolescent children, household income and family type— to calculate the adjusted odds ratios for adolescent health behaviors and mental health outcomes. Statistical significance was determined by a p-value of less than 0.05, and 95% confidence intervals were reported. All the statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1. The proportion of adolescents with parental depression was 5.00% (n = 203). Among participants with parental depression, there was a higher percentage of households with the lowest income level (< 2,000 — 30.1%) and a higher prevalence of single-parent family structures (26.4%) than those without parental depression (p < 0.05).

Adolescent health behaviors

In the study results, no significant differences were found in the risks of abnormal weight, smoking, alcohol consumption or physical activity based on parental depression (Table 2). However, boys had higher prevalence rates of smoking, alcohol consumption, and physical activity regardless of parental depression. In addition, no significant differences were observed in the risk of abnormal weight, smoking, alcohol consumption, or physical activity based on the severity of parental depression (Table 3). Although there were no statistically-significant differences in the proportions of abnormal weight, current smokers, alcohol drinkers, and recommended levels of physical activity between the two groups of adolescents with and without parental depression, Table 4 shows that the crude proportions of abnormal weight and alcohol consumption were higher when parents had been treated for depression, when depression was present, and when more than five years had elapsed since the diagnosis of parental depression. Additionally, adolescents with parents who were treated for depression and who were currently depressed had lower levels of physical activity.

Adolescent mental health

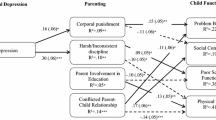

After multivariate adjustments, Table 2 shows that the increased risks of depressive mood were statistically significant in boys with parental depression (aOR = 2.46, 95% Confidential Interval (CI) = 1.22–4.96). The risks of very high and high stress levels for both boys and girls were significantly higher when adolescents had parental depression (stress levels for boys = aOR, 2.20, 95% CI = 1.35–3.58. Stress levels in girls: aOR = 1.66, 95% CI = 1.00–2.75). The risk of very poor or poor subjective health only increased in girls with parental depression (aOR = 2.54, 95% CI = 1.21–5.32).

When parents had moderate to severe depression, the risk of adolescent stress and depressive mood increased significantly after multivariate adjustments (stress: aOR = 1.81, 95% CI = 1.01–3.24; depressive mood: aOR = 2.6, 95% CI = 1.17–5.77 — Table 3). In addition, subjective health and distress were significantly higher among adolescents with parental depression (subjective health: aOR = 1.897, 95% CI = 1.05–3.36; distress: aOR = 1.91, 95% CI = 1.33–2.76 — Table 4). However, depressive mood did not differ significantly between adolescents with and without parental depression (aOR = 1.33, 95% CI = 0.77–2.28).

Among adolescents with parental depression, those with parents who were treated for depression and who currently had depression had significantly higher subjective health statuses and stress levels than.

those without parental depression (Table 4). The risk of very high or high stress levels was also significantly higher when parents were not treated for depression (aOR = 2.01, 95% CI = 1.25–3.22). If the duration of depression of parents exceeds 5 years, stress levels were significantly high (aOR = 2.29, 95% CI = 1.83–4.57).

Discussion

This study shows that parental depression can have the association of several aspects of adolescents’ mental health, including depressive mood, stress levels, and subjective health status. These effects were not only influenced by the adolescents’ gender, but also by factors such as parents’ current depression, treatment for depression, severity of depression, and time since diagnosis.

In the present study, boys whose parents were diagnosed with depression showed an higher risk of experiencing depressive mood and elevated stress than in girls. These findings differ from previous studies suggesting that girls are more vulnerable to parental depression [3, 34, 35], possibly due to their heightened sensitivity to interpersonal relationships and susceptibility to their parents’ emotional state [36,37,38]. Specifically, in Asian cultures, there is an expectation for children to financially support their caregivers, with male children, in particular, having significant responsibility for economic support [39]. Therefore, male children may face challenges in discussing their difficulties with caregivers due to these responsibility for supporting financial burdens. While previous research indicated that male children of parents with illness exhibit more externalizing problem behaviors compared to female children [40, 41], this study did not observe problematic behaviors, which is considered a limitation of the research. Consistent with reports indicating a higher suicide rate among Korean boys compared to girls [42], these findings underscore the need for careful management of boys with parental depression to address their mental health conditions.

Aligned with findings indicating that chronic and severe parental depression symptoms have more adverse effects on adolescents’ mental health [10, 43,44,45], this study confirms that severe parental depression symptoms, the duration of depression longer than 5 years, and current depression are associated with an increased risk of adverse adolescent mental health. These results in a Korean population-based study can be explained by the biopsychosocial model of depression [46, 47], referred to as thea association of parental depression on children’s mental health being a complex interaction of factors such as biological vulnerability, psychological factors, and social factors. First, as a biological vulnerability factor, children of parents with depression have a higher genetic vulnerability to depression [48]. For instance, Weissman et al. reported that, after following children for 20 years, those with depressed parents had more than three times the risk of developing depression and anxiety disorders compared to children without parental depression [6]. Second, as a psychological factor, severe and prolonged depressive symptoms in parents may interfere with their ability to fulfill their parenting role, leading to withdrawal or intrusiveness, which may exacerbate depression and stress in adolescents [49,50,51]. In addition, parental depression symptoms negatively affect parenting styles, worsen parent-child relationship interactions, and increase stress in children [52,53,54]. Third, as a social factor, parents with depression are more likely to experience unemployment and have lower household incomes [55]. Consequently, the deterioration of the economic situation for parents with depression can make it difficult for their children to find employment themselves or access educational opportunities, which may negatively impact their mental health and academic performance [56]. Especially, in light of the competitive social atmosphere prevalent in Asian cultures, the pressure of meeting parental expectations and parental interference in academic matters could serve as significant stressors for adolescents in Asian countries [57]. Therefore, our findings highlight the importance of comprehensive approach and earlier interventions in preventing parental depression from becoming more chronic and severe symptoms.

Contrary to previous research suggesting that treating depression in parents has a beneficial effect on the mental well-being of adolescents [8, 9], this study found that the stress levels and subjective health status of adolescents whose parents received treatment for depression were more vulnerable. Table s1 shows that the proportion of patients with mild and/or moderate to severe depression was higher in the treatment group (see Additional file 1). Despite South Korea being among the OECD countries with the highest annual outpatient visits and inpatient admissions, psychiatric clinic visits are relatively low due to the social stigma associated with mental illness [58]. Consequently, delayed treatment by parents with depression may lead to an increased severity of depressive symptoms, which may negatively affect their adolescent children. Therefore, efforts are required to improve negative perceptions about mental illness to ensure that parents with mental health conditions receive timely psychiatric treatment.

Although parental depression did not have a significant effect on adolescents’ negative health behaviors and physical activity, the results showed that adolescents with parental depression had a poorer subjective health status. While subjective health status serves as a factor reflecting how adolescents comprehensively perceive their health conditions and is linked to both mental and physical health [59, 60], it may not accurately represent the individual states of participants concerning variations in depressive symptoms and stress levels. However, consistent with parental depression potentially leading to adolescents’ anxiety or concerns about their own physical health [61], these findings suggest the possibility of hypochondriasis [62], considering that physical symptoms (loss of appetite, digestive problems, headaches, etc.) can manifest in individuals with depressive mood and psychological distress. Therefore, interventions that can help ensure the health status of adolescents should be considered along with the treatment of parental depression, as it may exacerbate adolescents’ concerns or anxiety about their subjective health status.

Our study has several strengths, including the use of nationwide data sources, which facilitates comparisons of outcomes within a wider adolescent population. In addition, the use of a community-based design enhanced the ability of the study to reflect the real-life circumstances of families dealing with depression, unlike a hospital-based study. Furthermore, we had comprehensive access to information regarding the physical and psychosocial welfare of adolescents with and without parental depression. The results of our study have significant implications for future interventions, emphasizing the importance of prioritizing the screening and management of adolescents’ mental health after diagnosing parental depression while also crucially evaluating their health behaviors. Future research should focus on exploring interventions that address the needs of families with parents with depression to reduce the psychological risks for their adolescent children.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations that need to be considered. First, the assessment of adolescents’ mental health status was limited to a single question, which posed challenges in accurately assessing and categorizing specific psychiatric diagnoses, such as anxiety disorder, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Second, although the clinical manifestations and hospitalization of parental depression may allow researchers to better confirm the difference between adolescents with parental depression and the general population, we did not consider the duration and frequency of parental symptoms of depression, hospitalization rates for depression, and treatment options for depression, which were not captured by the questionnaires. Finally, we encountered difficulties in obtaining relevant information about adolescents’ medical histories, including psychiatric conditions, other chronic illnesses, school absenteeism, and academic performance.

Conclusions

We concluded that Korean adolescents with parental depression have poorer mental health status than whose parents did not have mental health issues. Specifically, we identified that depressive mood over two weeks among adolescents with parental depression was more prevalent in boys and in cases where parents exhibited moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms. Additionally, when parental depression was present and the time since depression diagnosis was more than five years, adolescents with parental depression exhibited even poorer subjective health status and higher stress levels. However, adolescents with parental depression did not differ in their health behaviors compared to their general peers. These results highlight the need for tailored, community-based social support for adolescents with parental depression to promote their psychological well-being and encourage healthy behaviors as they transition into adulthood.

Data availability

The KNHANES database which support this study are available from the KNHANES website (knhanes.kdca.go.kr, Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency).

Abbreviations

- KNHANES:

-

Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- OR:

-

Odd Ratio

- aOR:

-

adjusted Odd Ratio

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- OECD:

-

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- ACSM:

-

American College of Sports Medicine

References

APA APA. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. The American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

Evans-Lacko S, et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1560–71.

Sieh DS, Visser-Meily JMA, Meijer AM. The relationship between parental depressive symptoms, family type, and adolescent functioning. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(11):e80699.

Lee YJ, Lee SI, Han K. Influence of parental stress, depressed mood, and suicidal ideation on adolescents’ suicidal ideation: the 2008–2013 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:571–7.

Brophy S, et al. Timing of parental depression on risk of child depression and poor educational outcomes: a population based routine data cohort study from born in Wales, UK. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(11):e0258966.

Weissman MM, et al. Offspring of depressed parents: 20 years later. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):1001–8.

Goodman SH, et al. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14:1–27.

van Loon LM, Granic I, Engels RC. The role of maternal depression on treatment outcome for children with externalizing behavior problems. J Psychopathol Behav Assess. 2011;33:178–86.

Weissman MM, et al. Treatment of maternal depression in a medication clinical trial and its effect on children. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(5):450–9.

Hammen C, Brennan PA. Severity, chronicity, and timing of maternal depression and risk for adolescent offspring diagnoses in a community sample. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(3):253–8.

Eaton DK, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. Morbidity Mortal Wkly Rep Surveillance Summaries (Washington DC: 2002). 2008;57(4):1–131.

Park H, Lee K-S. The association of family structure with health behavior, mental health, and perceived academic achievement among adolescents: a 2018 Korean nationally representative survey. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Glied S, Pine DS. Consequences and correlates of adolescent depression. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(10):1009–14.

Keijser R, et al. The influence of parenting styles and parental depression on adolescent depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional and longitudinal approach. Mental Health Prev. 2020;20:200193.

Chen C. The relationship between parental depression and child internalizing and externalizing problems: the roles of parenting stress and child maltreatment. Front Public Health. 2023;11:962951.

Liu F, et al. Brief report: parenting stress among Chinese and Dutch caregivers of children with autism. Res Autism Spectr Disorders. 2023;107:102224.

Kong KA, Choi HY, Kim SI. Mental health among single and partnered parents in South Korea. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(8):e0182943.

Oh BC, et al. Correlation between private education costs and parental depression in South Korea. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–10.

Shorey S, et al. Prevalence and incidence of postpartum depression among healthy mothers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;104:235–48.

Ahn S-Y, Baek H-J. Academic Achievement-Oriented Society and Its Relationship to the Psychological Well-Being of Korean Adolescents, in The Psychological Well-being of East Asian Youth. 2012. p. 265–279.

Park S, Jang H. Correlations between suicide rates and the prevalence of suicide risk factors among Korean adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2018;261:143–7.

Roh B-R, Jung EH, Hong HJ. A comparative study of suicide rates among 10–19-year-olds in 29 OECD countries. Psychiatry Invest. 2018;15(4):376.

Oh C-M et al. Changes in health behaviors and obesity of Korean adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a special report using the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Epidemiol Health, 2023. 45.

Kweon S, et al. Data resource profile: the Korea national health and nutrition examination survey (KNHANES). Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(1):69–77.

Smith SR, Soliday E. The effects of parental chronic kidney disease on the family. Fam Relat. 2001;50(2):171–7.

Kim KH, et al. Health behaviors and psychological burden of adolescents after parental cancer diagnosis. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):21018.

Bajaj JS, et al. The multi-dimensional burden of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy on patients and caregivers. Official J Am Coll Gastroenterology| ACG. 2011;106(9):1646–53.

Bell MF, et al. Developmental vulnerabilities in children of chronically ill parents: a population-based linked data study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2019;73(5):393–400.

Datta BK, et al. The influence of parent’s Cardiovascular morbidity on child Mental Health: results from the National Health interview survey. Children. 2023;10(1):138.

Cho YJ, et al. Parental smoking and depression, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2005–2014. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2018;10(3):e12327.

Kim CH, Kim SH, Lee JS. Association of maternal depression and allergic diseases in Korean children. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38(4):300–8.

Kim J, et al. Committee for the development of growth standards for Korean children and adolescents; Committee for school health and public health statistics, the Korean Pediatric Society; Division of health and nutrition survey, Korea centers for disease control and prevention. The 2017 Korean national growth charts for children and adolescents: development, improvement, and prospects. Korean J Pediatr. 2018;61(5):135–49.

Park S-J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9). Anxiety mood. 2010;6(2):119–24.

Chen M, et al. Parent and adolescent depressive symptoms: the role of parental attributions. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2009;37:119–30.

Connelly J, O’Connell M. Gender differences in vulnerability to maternal depression during early adolescence: girls appear more susceptible than boys. Psychol Sch. 2022;59(2):297–315.

Goodyer IM, Altham P. Lifetime exit events and recent social and family adversities in anxious and depressed school-age children and adolescents—I. J Affect Disord. 1991;21(4):219–28.

Rudolph KD. Gender differences in emotional responses to interpersonal stress during adolescence. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(4):3–13.

Shih JH, et al. Differential exposure and reactivity to interpersonal stress predict sex differences in adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2006;35(1):103–15.

Zi Y, Chengcheng S. Gender role attitudes and values toward caring for older adults in Contemporary China, Japan, and South Korea. J Asian Sociol. 2021;50(3):431–64.

Bongers IL, Koot HM, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. The normative development of child and adolescent problem behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112(2):179–92.

Vaalamo I, Pulkkinen L, Kinnunen T, Kaprio J, Rose RJ. Interactive effects of internalizing and externalizing problem behaviors on recurrent pain in children. J Pediatr Psychol. 2002;27(3):245–57.

Son JY, et al. Korean adolescent suicide and search volume for self-injury on internet search engines. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1186754.

Foster CE, et al. Course and severity of maternal depression: associations with family functioning and child adjustment. J Youth Adolesc. 2008;37:906–16.

Eckshtain D, et al. Parental depressive symptoms as a predictor of outcome in the treatment of child depression. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2018;46:825–37.

Brennan PA, et al. Chronicity, severity, and timing of maternal depressive symptoms: relationships with child outcomes at age 5. Dev Psychol. 2000;36(6):759.

Garcia-Toro M, Aguirre I. Biopsychosocial model in Depression revisited. Med Hypotheses. 2007;68(3):683–91.

Rice F, et al. Family conflict interacts with genetic liability in predicting childhood and adolescent depression. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(7):841–8.

Shadrina M, Bondarenko EA, Slominsky PA. Genetics factors in Major Depression Disease. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:334. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00334. PMID: 30083112; PMCID: PMC6065213.

Jaser SS, et al. Coping with the stress of parental depression II: adolescent and parent reports of coping and adjustment. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2005;34(1):193–205.

Jaser SS, et al. Cross-situational coping with peer and family stressors in adolescent offspring of depressed parents. J Adolesc. 2007;30(6):917–32.

Langrock AM, et al. Coping with the stress of parental depression: parents’ reports of children’s coping, emotional, and behavioral problems. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2002;31(3):312–24.

Gordon C, Beresin E, Herzog DB. The parents’ relationship and the child’s illness in anorexia nervosa. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1989;17(1):29–42.

Simons RL et al. Childhood experience, conceptions of parenting, and attitudes of spouse as determinants of parental behavior. J Marriage Fam, 1993: p. 91–106.

Jaser SS, et al. Maternal sadness and adolescents’ responses to stress in offspring of mothers with and without a history of depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2008;37(4):736–46.

Kinge JM, Øverland S, Flatø M, Dieleman J, Røgeberg O, Magnus MC, Evensen M, Tesli M, Skrondal A. Camilla Stoltenberg, Stein Emil Vollset, Siri Håberg, Fartein Ask Torvik, parental income and mental disorders in children and adolescents: prospective register-based study. Int J Epidemiol. October 2021;50(5):1615–27.

Shen H, Magnusson C, Rai D, Lundberg M, Le-Scherban F, Dalman C, Lee BK. Associations of parental depression with child school performance at age 16 years in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):239–46.

Yim EP-Y. Effects of Asian cultural values on parenting style and young children’s perceived competence: A cross-sectional study. 2022.

Hewlett E, et al. Tackling the mental health impact of the COVID-19 crisis: an integrated, whole-of-society response. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); 2021.

Hwang HR, Kim Y-J. Effects of sleep patterns on the subjective health status in older men from the 7th Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2016. Annals of geriatric medicine and research, 2020. 24(2): p. 107.

Niti M, et al. Depression and chronic medical illnesses in Asian older adults: the role of subjective health and functional status. Int J Geriatric Psychiatry: J Psychiatry late life Allied Sci. 2007;22(11):1087–94.

Scarella TM, et al. The relationship of hypochondriasis to anxiety, depressive, and somatoform disorders. Psychosomatics. 2016;57(2):200–7.

Noyes R Jr, et al. Childhood antecedents of hypochondriasis. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(4):282–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No financial support for the research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SIK formulated the research question, designed the study, analyzed the data, and drafted the paper. SMK, SJP, JS and JL contributed to the study’s design, data analysis, and paper revisions. KHK and SMP assisted with formulating the research question, interpreting the data, and supervising the paper’s writing quality. The final version of the manuscript was reviewed, feedback was provided, and confirmation was given by all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for the study protocol was granted by the Ethics Committee of Seoul National University Hospital (IRB number E-2304-102-1425). No consent to participate was used in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, SI., Kim, S.M., Park, S.J. et al. Association of parental depression with adolescent children’s psychological well-being and health behaviors. BMC Public Health 24, 1412 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18337-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18337-9