Abstract

Background

Adhering to varenicline has been shown to significantly improve the chances of successfully quitting smoking, with studies indicating a twofold increase in 6-month quit rates. However, despite its potential benefits, many individuals struggle with maintaining good adherence to varenicline; thus there is a need to develop scalable strategies to help people adhere. As a first step to inform the development of an intervention to improve adherence to varenicline, we conducted a rapid literature review to identify: 1) modifiable barriers and facilitators to varenicline adherence, and 2) behaviour change techniques associated with increased adherence to varenicline.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Embase, APA PsycINFO, CINAHL, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for relevant studies published between 2006 and 2022. Search terms included “varenicline,” “smoking cessation,” and "adherence," and their respective subject headings and synonyms. We screened and included studies reporting modifiable determinants of adherence to varenicline and then assessed quality, extracted modifiable determinants and mapped them to the Theoretical Domains Framework version 2 and the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1.

Results

A total of 1,221 titles were identified through the database searches; 61 met the eligibility criteria. Most of the studies were randomized controlled trials and predominantly focused on barriers to varenicline. Only nine studies explicitly mentioned behaviour change techniques used to help varenicline adherence. Eight domains were identified as barriers to varenicline adherence (behavioural regulation, memory, goals, intentions, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, optimism/pessimism, and environmental context) and five as facilitators (knowledge, behavioural regulation, beliefs about capabilities, social influences, and environmental context).

Conclusions

This study identifies barriers and facilitators that should be addressed when developing a complex adherence intervention tailored to patients’ needs based on modifiable determinants of medication adherence, some of which are under- used by existing adherence interventions. The findings from this review will inform the design of a theory-based healthbot planned to improve varenicline adherence in people undergoing smoking cessation treatment.

Systematic review registration

This study was registered with PROSPERO (# CRD42022321838).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tobacco use and exposure results in more than eight million deaths worldwide each year [1], prompting an urgent need to implement interventions to promote smoking cessation. There are currently three pharmacotherapies approved for smoking cessation by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA): varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) [2]. A Cochrane systematic review reported that, compared to bupropion or NRT, varenicline is the most effective pharmacotherapy for maintaining long-term smoking abstinence (at six months or more) [3]. A high-affinity partial agonist at the α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, varenicline decreases the rewarding effects of tobacco through its dual effects as an agonist by binding to the receptor to reduce craving and as an antagonist by competing with nicotine for the receptor [2, 4]. Despite varenicline being superior to other pharmacotherapy in the treatment of tobacco dependence, low adherence to varenicline is a significant obstacle to the success of this smoking cessation treatment [5]. Meta-analyses have demonstrated the association between varenicline and adverse effects such as nausea, constipation, flatulence [6], sleeping disorders, insomnia, abnormal dreams, and fatigue [7]. In a retrospective cohort study examining varenicline adherence, 55% of the study participants never began their 12-week treatment, 20% began but failed to complete their treatment, and only 25% of the participants adhered to and completed their treatment [5].

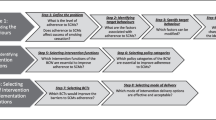

Studies have shown that providing behavioural supports and tailored interventions can increase adherence to smoking cessation medications [8].These studies have a large variability in the strengths of effects [9,10,11,12] which may be accounted for by the active ingredients in the behavioural supports the intervention offered. In addition, there is no review examining the behaviour change theory that could guide the design of the intervention targeting varenicline adherence. This is a significant shortcoming given that there is growing evidence, including the UK Medical Research Council's (MRC) framework for complex interventions [13] supporting the use of theory in complex interventions. Theory holds the potential to enhance researchers' comprehension of the behavior change process and provide guidance in the development and refinement of interventions [14]. For instance, theory can help identify theoretical constructs to target within the intervention (e.g. 'optimism.'). Therefore, before designing an intervention to help people adhere to their varenicline treatment, it is essential to conduct a review exploring modifiable determinants that influence varenicline adherence, grounded in a theoretical framework. The Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1 (BCTTv1) provides a practical taxonomy to describe the active content of an intervention [15]. Behaviour change techniques (BCTs) can be mapped to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [16], a framework that integrates 33 theories and 128 constructs into a single framework that contains 14 domains [17]. The TDF, in turn, can be mapped to a well-established model of behaviour change: the Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Model of Behaviour (COM-B). COM-B suggests that behaviour change results from an interaction between people’s capability, motivation, and opportunities for the behaviour [18].

The aim of this rapid review is twofold: 1) to identify the modifiable barriers and facilitators to varenicline adherence in people using varenicline for smoking cessation, and 2) to identify the behaviour change techniques associated with helping people adhere to their varenicline treatment.

The findings from this review will inform the design of a theory-based healthbot planned to improve varenicline adherence in people undergoing smoking cessation treatment.

Methods

We chose to conduct a rapid review since it is a timely, cost-effective and efficient way to gather high-quality evidence to inform health program decisions [19]. The rapid review was conducted in accordance with the Cochrane rapid review methods recommendations [20] and it is reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (see Additional file 1) [21]. The study was registered with PROSPERO (# CRD42022321838).

Eligibility criteria

The research question was developed using the PICO model.

-

Population: The population of interest were individuals using varenicline for smoking cessation.

-

Intervention: Studies were included if varenicline was used as an intervention for smoking cessation. We included studies using multiple smoking cessation medications, as long as they reported factors associated with only varenicline users separately.

-

Comparator: In studies with a comparator group, the comparator was either a placebo, an active control group, or no intervention

-

Outcome: The outcome of interest was reported modifiable factors associated with adherence to varenicline.

Exclusion criteria

-

1.

Publications such as commentaries, abstracts, conference papers, reviews, editorial letters, protocols, book chapters, thesis/dissertations, case reports, and case series.

-

2.

Studies that did not separately report barriers and/or facilitators associated directly with varenicline adherence.

-

3.

Studies in which varenicline was not administered for smoking cessation.

-

4.

Non-English language articles.

-

5.

Non-peer reviewed articles.

Information sources and search strategy

The search strategy was developed with a health sciences librarian (TR), who conducted all searches. The strategy was tested and finalized in MEDLINE (Ovid), then translated and run in the following bibliographic databases: MEDLINE, Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), APA PsycInfo, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

The search strategy was designed to identify the overlap between three concepts: tobacco smoking, varenicline, and treatment adherence (see Additional file 1). The smoking concept was kept broad (e.g. “smoking”, “nicotine”, “tobacco” and relevant subject headings) and functioned only to omit alternative uses of varenicline (i.e. treatment of dry eye syndrome) [22]. The varenicline concept included generic, and brand names (“varenicline”, “Chantix”, “Champix”) searched in the major record fields.

The treatment adherence concept used database-specific subject headings, natural language keywords, and advanced search operators such as truncation and adjacency operators to balance specificity and sensitivity. Variations of search terms such as “retention”, “dropout”, and “compliance” were searched in the title, subject heading, and keyword fields and were linked with “therapy” or “treatment” or “program” using an adjacency operator to search the abstract field. Terms such as “barrier” and “facilitator” were searched in the title, subject heading, and keyword fields and were linked with treatment or retention terms using an adjacency operator to search the abstract field.

The terms and concepts were combined using Boolean operators. Non-human animal studies were excluded [23], as were the following publication types when possible: book chapters, dissertations, conference abstracts, editorials, and letters. Year limit applied was 2006 to the date of the search (May 6, 2022) to reflect the FDA’s approval year of varenicline [24]. The core MEDLINE search strategy can be found in Additional file 2.

The studies located by the research librarian were imported into the reference manager, EndNote [25], and then uploaded into the systematic review software, Covidence [26]. Articles with duplicates were tagged and removed in Covidence [26].

Study selection process

All reviewers conducted a pilot exercise on Covidence to calibrate and evaluate the review forms used in the title and abstract screening, full-text screening, data extraction, and quality assessment. For the pilot screening, all reviewers conducted title and abstract screening on 39 studies and conducted full-text screening on five randomly selected studies that were included in the title and abstract screening stage [20].

Two reviewers independently screened 201 studies for the title and abstract screening, which included resolved conflicts. Afterwards, one reviewer screened the remaining abstracts while a second reviewer screened the abstracts deemed irrelevant by the first reviewer. Given that modifiable factors associated with varenicline adherence could not always be determined in the title and abstract, only the “yes” and “no” options on Covidence were used in the title and abstract screening, where “yes” was selected if the abstract was ambiguous or suggested the reporting of barriers and/or facilitators to varenicline adherence. Studies with missing abstracts also received a vote for “yes” and eligibility was determined in full-text screening. Two reviewers were required for full-text screening, where one reviewer screened all the included full-text articles (MW) while a second reviewer screened the full-text articles excluded by the first reviewer. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer or by consensus [20].

Data extraction

Utilizing the revised data extraction form from the pilot (see Additional file 3), data extraction was performed by two reviewers. One reviewer extracted data using the data extraction form and a second reviewer verified the accuracy and completeness of the data extracted by the first reviewer. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer or by consensus [20]. Missing data were obtained by contacting the corresponding authors of the included studies. Extracted data included:

-

1. Barriers and facilitators associated with varenicline adherence.

-

2. “Active ingredients” employed by the varenicline adherence intervention, defined as the components of a behaviour intervention that are needed for it to work and are observable, replicable and irreducible [25],

-

3. Study information including: sample size, location of intervention, study design, theories used to design the intervention, delivery of intervention, method of smoking cessation (e.g., abrupt cessation, gradual cessation via reduction), and type of tobacco product used.

-

4. Demographic information: gender proportion, target population of intervention, age, race, and any additional demographic information reported.

-

5. Information regarding varenicline adherence including: definition of varenicline adherence, adherence outcome measures (e.g., self-report, pill count), and degree of non-adherence (e.g. discontinuation, reduction). For studies in which adherence to varenicline was not the primary outcome, adherence was defined as adherence to the varenicline treatment. Participants who failed to adhere to their varenicline treatment (e.g., discontinued or stopped taking varenicline but were still in the study) were considered non-adherent.

Barriers and facilitators associated with varenicline adherence were extracted and defined according to the TDF, version 2 [27]. For studies that aimed at improving varenicline adherence, we used BCTTv1 [15] to extract data on the components of the intervention (active ingredients).

Methodological quality assessment

We used the Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools [28] to assess the quality of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental, analytical cross-sectional, case–control, cohort, and qualitative studies, and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 [29] to assess the quality of mixed methods studies. For studies using the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool, an overall score was calculated based on the percentage of “Yes” answered, and questions were excluded from the overall score if “Not applicable” was answered. Studies with an overall score of 70% and above were deemed low risk of bias, studies with a score between 40 and 70% were deemed moderate risk of bias, and studies with a score of 40% and below were deemed high risk of bias [30]. Secondary and pooled analyses were assessed using the RCT checklist, and reference was made to the parent study. Since the use of an overall score to determine the quality of a study is not recommended for the MMAT, a detailed presentation of the quality assessment was provided for all included studies using the methodological quality criteria from the MMAT to determine whether it was of high, moderate, or low risk of bias [31].

The quality assessment was performed by two reviewers. One reviewer rated all included studies using the quality assessment form and a second reviewer verified the appraisal made by the first reviewer [20]. Conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer or by consensus.

Data synthesis

We used a narrative synthesis of the included studies [20] to summarize the barriers and facilitators to varenicline adherence and the active ingredients in interventions that aim to help people adhere to varenicline. Barriers and facilitators were coded based on the 14 domains of the TDF (version 2). Active ingredients were coded based on the 16 groups of the BCTTv1. All reviewers were trained to code using the TDF and BCTTv1 (http://www.bct-taxonomy.com/). Discrepancies in coding were resolved by consensus or by an expert in TDF and BCTs (NM).

In order to understand which BCTs helped with adherence, we categorized the interventions into three simple categories: ‘effective’, ‘mixed results’ or ‘ineffective’. An intervention was categorized as ‘effective’ when improvements to medication adherence were reported to be statistically significant compared to the control group or baseline measures. Interventions were categorized as having ‘mixed results’ when the BCTs increased the participants’ knowledge, skills, or motivation but showed no sign of improving medication adherence. Interventions were categorized as ‘ineffective’ when the intervention did not significantly improve medication adherence compared to the control group or baseline measure.

Studies with low and moderate risk of bias were used to examine barriers and facilitators to varenicline adherence. In contrast, studies with high risk of bias were only used to confirm the patterns identified.

Results

A total of 1,221 titles were identified through the database searches; 61 met the eligibility criteria (see Fig. 1). Of these 61 studies, nine reported BCTs used to help participants adhere to varenicline.

Study characteristics

Most of the studies included in this review consisted of RCTs (n = 38) [32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69], followed by cohort (n = 17) [70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86], cross-sectional (n = 3) [87,88,89], quasi-experimental (n = 3) [90,91,92], and qualitative (n = 1) [93] studies, and one study (n = 1) [53] was a mediation analysis that examined an observational study and RCT. The majority of studies had a low to moderate risk of bias [27 studies were of low risk of bias [37,38,39, 42, 44, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56, 61, 65, 71,72,73, 75, 83, 84, 86, 88, 92, 93]; 28 studies were of moderate risk [32, 33, 35, 40, 41, 43, 45, 46, 59, 60, 62,63,64, 66,67,68,69,70, 77,78,79,80,81,82, 85, 87, 89, 90]; and six studies were of high risk of bias [36, 57, 58, 74, 76, 91]]. Studies were conducted in a multitude of countries across all continents except Antarctica.

All studies focused on adult populations, and most focused on the general public (n = 43) [32, 33, 35, 37, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45, 48,49,50,51,52,53, 55, 59, 60, 62, 63, 65, 67, 69,70,71,72,73,74, 76, 77, 79,80,81, 83, 85,86,87,88, 90, 91, 93]. A few studies investigated specific patient populations: cancer (n = 3) [34, 36, 82]; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (n = 3) [61, 75, 78]; human immunodeficiency viruses (n = 3) [54, 58, 66]; psychiatric conditions (n = 2) [46, 84]; and people undergoing substance use disorder treatment, including methadone treatment (n = 2) [47, 56]. There was a fairly even gender split among participants in the included studies, although 20 studies reported 30% or fewer female participants [71, 72, 38, 39, 77,78,79, 46, 48, 80, 81, 89, 54, 84, 55, 58, 92, 65, 66, 86]. Table 1 provides a summary of the included studies.

Barriers and facilitators – by Theoretical Domains

Most studies included in this review reported barriers as opposed to facilitators. Of the 61 studies, 51 studies [32, 33, 36,37,38,39,40, 42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65, 67,68,69, 71, 73,74,75,76,77,78, 80,81,82,83, 86,87,88,89,90,91,92] only mentioned barriers, while four studies [41, 58, 66, 85] only mentioned facilitators, and six studies mentioned both barriers and facilitators [35, 37, 70, 79, 84, 93]. Definitions of the theoretical domains according to Atkins, et al. [94] can be found in Table 2.

‘Belief about consequences’ was the most common barrier to varenicline adherence, reported by 53 of the included studies. Moreover, 52 of these studies reported side effects as a barrier to adherence (27 of the studies were of low/moderate risk of bias). The most frequently reported adverse effects contributing to varenicline non-adherence were nausea (n = 23; 20 low/moderate risk of bias) [32, 40, 45,46,47, 49,50,51, 53, 57, 60, 62, 63, 65, 73, 75,76,77, 81, 82, 86, 89, 91]; insomnia/sleep problems (n = 12; 8 low/moderate risk of bias) [36, 39, 47, 54, 56, 57, 63, 65, 73, 76, 86, 91]; headache (n = 8; 7 low/moderate risk of bias) [40, 47, 63, 65, 73, 76, 81, 89]; depression (n = 7; 4 low/moderate risk of bias) [32, 36, 43, 56, 62, 76, 91]; vomiting (n = 6; 5 low/moderate risk of bias) [36, 43, 46, 47, 65, 77]; and abnormal dreaming (n = 5; 4 low/moderate risk of bias) [57, 73, 82, 86, 89].

Another frequently cited domain mentioned as a barrier to varenicline adherence was optimism/pessimism, which was reported in 17 studies (n = 17; 15 low/moderate risk of bias) [33, 35, 43, 50, 51, 55, 57, 73, 74, 79,80,81, 84, 86,87,88,89]. In these studies, participants discontinued their varenicline treatments as their confidence that varenicline would help them quit smoking diminished.

Ten studies (n = 10; 9 low/moderate risk of bias) [35, 43, 68, 73, 74, 78, 79, 84, 87, 88] mentioned beliefs about capabilities as a determinant of varenicline adherence. These studies reported perceived competence and/or low willpower as contributors to varenicline discontinuation.

Nine studies mentioned environmental context and resources (n = 9; 8 low/moderate risk of bias) [43, 52, 68, 74, 75, 78,79,80, 90] as a barrier to varenicline adherence. The cost of the medication and lack of access to pharmacies were the most frequent barriers coded under this domain.

Other less frequently reported barriers to varenicline adherence include: behavioural regulation (n = 3; 2 moderate risk of bias) [74, 79, 81]; memory, attention, and decision processes (n = 2; 2 low/moderate risk of bias) [68, 92]; goals (n = 1; 1 low risk of bias) [84]; and intentions (n = 1; 1 moderate risk of bias) [78].

Facilitators that promoted adhering to varenicline include: social influences (n = 4; 4 low/moderate risk of bias) [37, 41, 70, 79]; knowledge (n = 3; 2 low/moderate risk of bias) [37, 41, 58]; beliefs about capabilities (n = 3; 2 moderate risk of bias) [35, 58, 66]; environmental context and resources (n = 3; 3 low/moderate risk of bias) [79, 84, 85]; and behavioural regulation (n = 1; 1 low risk of bias) [93].

There were few instances where modifiable determinants related to ‘goals’ and ‘intentions’ were reported. When they were reported it was always as barriers. On the other hand, “knowledge and “social influence” were only mentioned as facilitators (Figs. 2 and 3). Table 2 provides a summary of the barriers and facilitators to varenicline adherence according to the Theoretical Domains Framework.

Behaviour change techniques

Only nine studies included in this review reported on behaviour change techniques associated with varenicline adherence [37, 41, 43, 56, 58, 66, 89, 92, 93]. Among these studies, two studies reported statistical significance in regards to improving varenicline adherence [43, 58], two studies were not statistically significant [37, 66], and five studies did not report statistical significance [41, 56, 66, 89, 93].

The most common behaviour change techniques (BCTs) implemented in the studies for improving varenicline adherence were social support (n = 6) [37, 41, 43, 56, 66, 93]; feedback and monitoring (n = 5) [41, 43, 56, 66, 93]; and shaping knowledge (n = 4) [37, 41, 58, 89]. Other BCTs that were mentioned included goals and planning (n = 2) [56, 89]; regulation (n = 2) [56, 89]; and self-belief (n = 1) [58]. Given that so few studies reported statistical significance, we did not identify any trends indicating which BCTs were promising. Table 3 provides a summary of the BCTs used in these studies.

Discussion

The goals for this rapid review were to identify: (1) the facilitators and barriers to adhering to varenicline; and (2) the active ingredients utilized in the intervention for varenicline adherence. The results of the review will be used by the authors to help design a healthbot aimed at helping people adhere to their varenicline regimen.

The current review identified 61 studies that identified barriers and/or facilitators to varenicline adherence. Of the 61 studies, nine explicitly mentioned behaviour change techniques used to help with varenicline adherence. Similar to what other evidence syntheses have found on medication adherence [95], our review found a greater emphasis on the barriers than on the facilitators.

By using the TDF framework to extract and analyze the data, we saw that there are eight domains that act as barriers to varenicline adherence (behavioural regulation, memory, goals, intentions, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, optimism/pessimism, and environmental context) and five domains that act as facilitators (knowledge, behavioural regulation, beliefs about capabilities, social influences, and environmental context). In this review, side effects were coded under the domains of ‘beliefs about consequences’ since we assumed it is not the side effects per se that influence medication adherence but more of an individual’s acceptance that the medication may cause some unpleasant side effects (such as nausea, sleep disturbances). Under this assumption, the patient’s initial belief that varenicline will lead to side effects may discourage them from beginning their varenicline treatment.

Our results align with other studies, which identified side effects, especially nausea, as a major determinant to varenicline adherence [34, 52]. Additionally, our results are in line with a review investigating factors influencing adherence to Nicotine Replacement Therapy among individuals aiming to quit smoking [96]. This review also identified beliefs about consequences, behavioural regulation, memory, intentions, beliefs about capabilities and environmental context as a significant determinant to medication adherence [96]. Researchers studying different populations (i.e. people with bio-polar disorder, diabetes), have also found beliefs about consequences as a significant determinant to medication adherence [95, 97].

With the exception of the role of optimism/pessimism as a determinant, our findings are similar to other studies using the TDF to understand the determinant of medication adherence [95, 98,99,100]. In our review, we identified 17 studies reporting pessimism as a barrier to varenicline adherence, which contrasts with the results of other reviews which did not identify pessimism/optimism as a determinant to medication adherence [95, 101]. While it might be a unique case that pessimism is a determinant for varenicline adherence and not to other medications, it is more likely that the difference is due to decisions on how to code certain determinants. Several researchers (who did not use the TDF in their studies) have identified pessimism as an important domain for medication adherence [102,103,104].

Similar to what other researchers have shown, we found that providing social support, feedback and monitoring, and shaping knowledge were the most common BCTs used to help people adhere to their medication regimen [105,106,107].

Strengths and limitations

Our search strategy was comprehensive and was developed with the help of an experienced health sciences research librarian. The included studies were conducted in several countries, and there was representation from all continents, with the exception of Antarctica. In addition, the included studies used a variety of study designs, allowing for a comprehensive list of modifiable determinants of varenicline adherence to be identified. However, due to the nature of rapid reviews, some relevant studies may not have been captured (e.g., exclusion of non-English publications, proceedings and relevant information in the gray literature).

Utilizing the TDF to organize our data, we were able to focus on modifiable determinants and, at the same time, map them to a well-defined theory of behaviour change. However, as mentioned earlier, there were some levels of subjectivity in coding for a few determinants.

Given that very few studies reported BCTs, and of those that did, most did not report the statistical significance of their results, we were unable to examine trends on what BCTs are promising when targeting varenicline adherence.

Conclusion

Using the TDF framework, our analysis revealed eight domains as barriers (behavioral regulation, memory, goals, intentions, beliefs about capabilities, beliefs about consequences, optimism/pessimism, and environmental context) and five domains as facilitators (knowledge, behavioral regulation, beliefs about capabilities, social influences, and environmental context) to varenicline adherence. The insights into these barriers and facilitators provide valuable guidance for healthcare providers and decision-makers in shaping the design and delivery of smoking cessation services incorporating varenicline. Future work will explore how a healthbot [108, 109] could address the barriers identified in this review.

Availability of data and materials

Any data extracted during the rapid review process can be provided for review. The extracted data analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- NRT:

-

Nicotine Replacement Therapy

- MRC:

-

Medical Research Council

- BCTTv1:

-

The Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

- COM-B:

-

Capability, Opportunity, and Motivation Model of Behaviour

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature

- BCTs:

-

Behaviour Change Techniques

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- MMAT:

-

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- CASP:

-

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme

References

World Health Organization. 2019. Tobacco. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco Cited 2022 Nov 18

Rigotti NA, Kruse GR, Livingstone-Banks J, Hartmann-Boyce J. Treatment of Tobacco Smoking: A Review. JAMA. 2022;327(6):566–77.

Cahill K, Stevens S, Perera R, Lancaster T. Pharmacological interventions for smoking cessation An overview and network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(5):CD009329.

Tonstad S, Arons C, Rollema H, Berlin I, Hajek P, Fagerström K, et al. Varenicline: mode of action, efficacy, safety and accumulated experience salient for clinical populations. Curr Med Res Opin. 2020;36(5):713–30.

Liberman JN, Lichtenfeld MJ, Galaznik A, Mastey V, Harnett J, Zou KH, et al. Adherence to varenicline and associated smoking cessation in a community-based patient setting. J Manag Care Pharm. 2013;19(2):125–31.

Leung LK, Patafio FM, Rosser WW. Gastrointestinal adverse effects of varenicline at maintenance dose: A meta-analysis. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2011;11(1):15.

Thomas KH, Martin RM, Knipe DW, Higgins JPT, Gunnell D. Risk of neuropsychiatric adverse events associated with varenicline: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Online). 2015;350:7–9.

Hollands GJ, Naughton F, Farley A, Lindson N, Aveyard P. Interventions to increase adherence to medications for tobacco dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;8:CD009164.

Mooney M, Babb D, Jensen J, Hatsukami D. Interventions to increase use of nicotine gum: a randomized, controlled, single-blind trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2005;7(4):565–79.

Mooney ME, Sayre SL, Hokanson PS, Stotts AL, Schmitz JM. Adding MEMS feedback to behavioral smoking cessation therapy increases compliance with bupropion: a replication and extension study. Addict Behav. 2007;32(4):875–80.

Nollen NL, Cox LS, Nazir N, Ellerbeck EF, Owen A, Pankey S, et al. A pilot clinical trial of varenicline for smoking cessation in black smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(9):868–73.

Tucker JS, Shadel WG, Galvan FH, Naranjo D, Lopez C, Setodji C. Pilot evaluation of a brief intervention to improve nicotine patch adherence among smokers living with HIV/AIDS. Psychol Addict Behav. 2017;31(2):148–53.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n2061.

Michie S. ABC of behaviour change theories. Silverback Publishing; 2014. Available from: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130282273236722816 Cited 2023 Dec 22

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W, et al. The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Ann Behav Med. 2013;46(1):81–95.

Cane J, Richardson M, Johnston M, Ladha R, Michie S. From lists of behaviour change techniques (BCTs) to structured hierarchies: Comparison of two methods of developing a hierarchy of BCTs. Br J Health Psychol. 2015;20(1):130–50.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):1–17.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42.

Moons P, Goossens E, Thompson DR. Rapid reviews: the pros and cons of an accelerated review process. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;20(5):515–9.

Garritty C, Gartlehner G, Nussbaumer-Streit B, King VJ, Hamel C, Kamel C, et al. Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:13–22.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;29:372.

Wirta D, Vollmer P, Paauw J, Chiu KH, Henry E, Striffler K, et al. Efficacy and safety of OC-01 (Varenicline Solution) nasal spray on signs and symptoms of Dry Eye Disease: The ONSET-2 Phase 3 Randomized Trial. Ophthalmology. 2022;129(4):379–87.

McGill University Health Centre (MUHC) Libraries. 2019. Excluding Animal Studies. https://www.muhclibraries.ca/training-and-guides/excluding-animal-studies/ Cited 2022 Dec 30

Drug Approval Package: Chantix (Varenicline) NDA #021928. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2006/021928_s000_chantixtoc.cfm Cited 2022 Apr 12

The EndNote Team. EndNote. Philadelphia: Clarivate; 2013.

Covidence systematic review software. Melbourne: Veritas Health Innovation;

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical framework. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

The Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools Cited 2022 Jun 25

Hong QN, Pluye P, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, et al. Improving the content validity of the mixed methods appraisal tool: a modified e-Delphi study. J Clin Epidemiol. 2019;111:49-59.e1.

Struik L, Rodberg D, Sharma RH. The Behavior Change Techniques Used in Canadian Online Smoking Cessation Programs: Content Analysis. JMIR Mental Health. 2022;9(3):1–12.

Nha HONG Q, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers.

Aubin HJ, Bobak A, Britton JR, Oncken C, Billing CBJ, Gong J, et al. Varenicline versus transdermal nicotine patch for smoking cessation: results from a randomised open-label trial. Thorax. 2008;63(8):717–24.

Bolliger CT, Issa JS, Posadas-Valay R, Safwat T, Abreu P, Correia EA, et al. Effects of varenicline in adult smokers: A multinational, 24-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2011;33(4):465–77.

Carroll A.J., Veluz-Wilkins A.K., Blazekovic S., Kalhan R., Leone F.T., Wileyto E.P., et al. Cancer-related disease factors and smoking cessation treatment: Analysis of an ongoing clinical trial. Psycho-Oncology. 2017;((Carroll, Veluz-Wilkins, Kalhan, Hitsman) Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine Chicago, IL USA(Blazekovic, Leone, Wileyto, Schnoll) University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine Philadelphia, PA USA). http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/10.1002/(ISSN)1099-1611

Catz SL, Jack LM, McClure JB, Javitz HS, Deprey M, Zbikowski SM, et al. Adherence to varenicline in the COMPASS smoking cessation intervention trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(5):361–8.

Crawford G, Weisbrot J, Bastian J, Flitter A, Jao NC, Carroll A, et al. Predictors of Varenicline Adherence among cancer patients treated for tobacco dependence and its association with smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(8):1135–9.

Ebbert J, Jimenez-Ruiz C, Dutro MP, Fisher M, Li J, Hays JT. Frequently reported adverse events with smoking cessation medications: post hoc analysis of a randomized trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2021;96(7):1801–11.

Eisenberg MJ, Windle SB, Roy N, Old W, Grondin FR, Bata I, et al. Varenicline for smoking cessation in hospitalized patients with acute coronary syndrome. Circulation. 2016;133(1):21–30.

Fagerstrom K, Gilljam H, Metcalfe M, Tonstad S, Messig M. Stopping smokeless tobacco with varenicline: randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c6549.

Fouz-Roson N, Montemayor-Rubio T, Almadana-Pacheco V, Montserrat-Garcia S, Gomez-Bastero AP, Romero-Munoz C, et al. Effect of 0.5 mg versus 1 mg varenicline for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2017;112(9):1610–9.

Gong J, Baker CL, Zou KH, Bruno M, Jumadilova Z, Lawrence D, et al. A pragmatic randomized trial comparing telephone-based enhanced pharmacy care and usual care to support smoking cessation. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2016;22(12):1417–25.

Gray KM, Rubinstein ML, Prochaska JJ, DuBrava SJ, Holstein AR, Samuels L, et al. High-dose and low-dose varenicline for smoking cessation in adolescents: a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(11):837–45.

Halperin AC, McAfee TA, Jack LM, Catz SL, McClure JB, Deprey TM, et al. Impact of symptoms experienced by varenicline users on tobacco treatment in a real world setting. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;36(4):428–34.

Hays JT, Leischow SJ, Lawrence D, Lee TC. Adherence to treatment for tobacco dependence: association with smoking abstinence and predictors of adherence. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(6):574–81.

Jorenby DE, Hays JT, Rigotti NA, Azoulay S, Watsky EJ, Williams KE, et al. Efficacy of varenicline, an alpha4ß2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, vs placebo or sustained-release bupropion for smoking cessation: a randomized controlled trial [corrected] [published erratum appears in JAMA 2006 Sep 20;296(11):1355]. JAMA. 2006;296(1):56–63.

Meszaros ZS, Abdul-Malak Y, Dimmock JA, Wang D, Ajagbe TO, Batki SL. Varenicline treatment of concurrent alcohol and nicotine dependence in schizophrenia: A randomized, placebo-controlled pilot trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;33(2):243–7.

Nahvi S, Adams TR, Ning Y, Zhang C, Arnsten JH. Effect of varenicline directly observed therapy versus varenicline self-administered therapy on varenicline adherence and smoking cessation in methadone-maintained smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2021;116(4):902–13.

Nakamura M, Abe M, Ohkura M, Treadow J, Yu C-R, Park PW. Efficacy of Varenicline for cigarette reduction before quitting in Japanese smokers: a subpopulation analysis of the reduce to quit trial. Clin Ther. 2017;39(4):863–72.

Niaura R, Hays JT, Jorenby DE, Leone FT, Pappas JE, Reeves KR, et al. The efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation using a flexible dosing strategy in adult smokers: a randomized controlled trial. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24(7):1931–41.

Nides M, Oncken C, Gonzales D, Rennard S, Watsky EJ, Anziano R, et al. Smoking cessation with varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist: results from a 7-week, randomized, placebo- and bupropion-controlled trial with 1-year follow-up. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(15):1561–8.

Nides M, Glover ED, Reus VI, Christen AG, Make BJ, Billing CBJR, et al. Varenicline versus bupropion SR or placebo for smoking cessation A pooled analysis. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(6):664–75.

Peng AR, Morales M, Wileyto EP, Hawk LWJ, Cinciripini P, George TP, et al. Measures and predictors of varenicline adherence in the treatment of nicotine dependence. Addict Behav. 2017;75:122–9 (2gw, 7603486).

Peng AR, Swardfager W, Benowitz NL, Ahluwalia JS, Lerman C, Nollen NL, et al. Impact of early nausea on varenicline adherence and smoking cessation. Addiction. 2020;115(1):134–44.

Quinn MH, Bauer AM, Flitter A, Lubitz SF, Ashare RL, Thompson M, et al. Correlates of varenicline adherence among smokers with HIV and its association with smoking cessation. Addict Behav. 2020;102:106151 (2gw, 7603486).

Rigotti NA, Pipe AL, Benowitz NL, Arteaga C, Garza D, Tonstad S. Efficacy and safety of varenicline for smoking cessation in patients with cardiovascular disease: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2010;121(2):221–9.

Rohsenow DJ, Tidey JW, Martin RA, Colby SM, Swift RM, Leggio L, et al. Varenicline versus nicotine patch with brief advice for smokers with substance use disorders with or without depression: effects on smoking, substance use and depressive symptoms. Addiction (Abingdon, England). 2017;112(10):1808–20.

Scoville EA, Tindle HA, Wells QS, Peyton SC, Gurwara S, Pointer SO, et al. Precision nicotine metabolism-informed care for smoking cessation in Crohn’s disease: A pilot study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(3):e0230656.

Shelley D, Tseng TY, Gonzalez M, Krebs P, Wong S, Furberg R, et al. Correlates of Adherence to Varenicline Among HIV+ Smokers. Nicotine Tob Res. 2015;17(8):968–74.

Stein MD, Caviness CM, Kurth ME, Audet D, Olson J, Anderson BJ. Varenicline for smoking cessation among methadone-maintained smokers: a randomized clinical trial. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(2):486–93.

Swan GE, Javitz HS, Jack LM, Wessel J, Michel M, Hinds DA, et al. Varenicline for smoking cessation: Nausea severity and variation in nicotinic receptor genes. Pharmacogenomics J. 2012;12(4):349–58.

Tashkin DP, Rennard S, Hays JT, Ma W, Lawrence D, Lee TC. Effects of varenicline on smoking cessation in patients with mild to moderate COPD: A randomized controlled trial. Chest. 2011;139(3):591–9.

Tonstad S. Smoking cessation efficacy and safety of varenicline, an alpha4ß2 nicotinic receptor partial agonist. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2006;21(6):433–6.

Tonstad S, Tønnesen P, Hajek P, Williams KE, Billing CB, Reeves KR, et al. Effect of maintenance therapy with varenicline on smoking cessation a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2006;296(1):64–71.

Tonstad S, Lawrence D. Varenicline in smokers with diabetes: A pooled analysis of 15 randomized, placebo-controlled studies of varenicline. J Diabetes Investig. 2017;8(1):93–100.

Tsai ST, Cho HJ, Cheng HS, Kim CH, Hsueh KC, Billing CBJ, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of varenicline, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist, as a new therapy for smoking cessation in Asian smokers. Clin Ther. 2007;29(6):1027–39.

Tseng TY, Krebs P, Schoenthaler A, Wong S, Sherman S, Gonzalez M, et al. Combining text messaging and telephone counseling to increase varenicline adherence and smoking abstinence among cigarette smokers living with HIV: a randomized controlled study. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1964–74.

Tulloch HE, Pipe AL, Els C, Clyde MJ, Reid RD. Flexible, dual-form nicotine replacement therapy or varenicline in comparison with nicotine patch for smoking cessation: A randomized controlled trial. BMC Med. 2016;14(1):80.

Walker N, Smith B, Barnes J, Verbiest M, Parag V, Pokhrel S, et al. Cytisine versus varenicline for smoking cessation in New Zealand indigenous Māori: a randomized controlled trial. Addiction. 2021;116(10):2847.

Williams KE, Reeves KR, Billing CBJ, Pennington AM, Gong J. A double-blind study evaluating the long-term safety of varenicline for smoking cessation. Curr Med Res Opin. 2007;23(4):793–801.

Boudrez H, Gratziou C, Messig M, Metcalfe M. Effectiveness of varenicline as an aid to smoking cessation: results of an inter-European observational study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(4):769–75.

Chu S, Liang L, Jing H, Zhang D, Tong Z. Safety of varenicline as an aid to smoking cessation in professional drivers and its impact on driving behaviors: An observational cohort study of taxi drivers in Beijing. Tobacco Induced Diseases. 2020;18:120935 (Chu, Liang, Jing, Zhang) Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Tobacco Dependence Treatment Research, Beijing Chaoyang Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, China(Chu, Liang, Jing, Zhang, Tong) Beijing Institute of Respiratory Medicine, Beijin).

Ebbert JO, Croghan IT, North F, Schroeder DR. A pilot study to assess smokeless tobacco use reduction with varenicline. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12(10):1037–40.

Grassi MC, Enea D, Ferketich AK, Lu B, Pasquariello S, Nencini P. Effectiveness of varenicline for smoking cessation: a 1-year follow-up study. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41(1):64–70.

Harrison-Woolrych M, Ashton J. Utilization of the smoking cessation medicine varenicline: an intensive post-marketing study in New Zealand. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(9):949–53.

Hernandez Zenteno RJ, Lara DF, Venegas AR, Sansores RH, Pineda JR, Trujillo FF, et al. Varenicline for long term smoking cessation in patients with COPD. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2018;53:116–20 (Hernandez Zenteno, Lara, Trujillo) COPD Clinic, National Institute of Respiratory Diseases, Calzada de Tlalpan 4502 Seccion XVI, Mexico City, PC 14080, Mexico(Venegas, Pineda, Perez Padilla) Department of Research in Tobacco Smoking and COPD, National In).

Hodgkin JE, Sachs DPL, Swan GE, Jack LM, Titus BL, Waldron SJS, et al. Outcomes from a patient-centered residential treatment plan for tobacco dependence. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(9):970–6.

Jimenez-Ruiz CA, Barrios M, Pena S, Cicero A, Mayayo M, Cristobal M, et al. Increasing the dose of varenicline in patients who do not respond to the standard dose. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1443–5.

Jimenez-Ruiz CA, Garcia Rueda M, Martinez Muniz MA, Sellares J, Jimenez-Fuentes MA, Lazaro Asegurado L, et al. Varenicline in smokers with severe or very severe COPD after 24 weeks of treatment A descriptive analysis VALUE study. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2017;87(3):874.

Jung JW, Jeon EJ, Kim JG, Yang SY, Choi JC, Shin JW, et al. Clinical experience of varenicline for smoking cessation. Clin Respir J. 2010;4(4):215–21.

Ock M, Shin JS, Ra SW. Safety and Effectiveness of Varenicline in Korean Smokers: A Nationwide Post-Marketing Surveillance Study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:413–26 ((Ock) Department of Preventive Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, South Korea(Shin) Medical Affairs, Pfizer Korea, Seoul, South Korea(Ra) Department of Internal Medicine, Ulsan University Hospital, Univers).

Park PW, Casiano EM, Escoto L, Claveria AM. Observational study of safety and efficacy of varenicline for smoking cessation among Filipino smokers. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(10):1869–75.

Park ER, Japuntich S, Temel J, Lanuti M, Pandiscio J, Hilgenberg J, et al. A smoking cessation intervention for thoracic surgery and oncology clinics: a pilot trial. J Thor Oncol. 2011;6(6):1059–65.

Pozzi P, Munarini E, Bravi F, Rossi M, La Vecchia C, Boffi R, et al. A combined smoking cessation intervention within a lung cancer screening trial: A pilot observational study. Tumori. 2015;101(3):306–11.

Raich A, Ballbe M, Nieva G, Cano M, Fernandez T, Bruguera E, et al. Safety of varenicline for smoking cessation in psychiatric and addicts patients. Subst Use Misuse. 2016;51(5):649–57.

van Boven JFM, Vemer P. Higher adherence during reimbursement of pharmacological smoking cessation treatments. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(1):56–63.

Wang C, Cho B, Xiao D, Wajsbrot D, Park PW. Effectiveness and safety of varenicline as an aid to smoking cessation: results of an inter-Asian observational study in real-world clinical practice. Int J Clin Pract. 2013;67(5):469–76.

Balmford J, Borland R, Hammond D, Cummings KM. Adherence to and reasons for premature discontinuation from stop-smoking medications: data from the ITC Four-Country Survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2011;13(2):94–102.

Etter JF, Schneider NG. An internet survey of use, opinions and preferences for smoking cessation medications: nicotine, varenicline, and bupropion. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15(1):59–68.

Purvis TL, Mambourg SE, Balvanz TM, Magallon HE, Pham RH. Safety and effectiveness of varenicline in a veteran population with a high prevalence of mental illness. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43(5):862–7.

Heydari G. Is cost of medication for quit smoking important for smokers, experience of using champix in Iranian smoking cessation program 2016. Int J Prev Med. 2017;8:63 ((Heydari) Tobacco Prevention and Control Research Center, National Research Institute of Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases, Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, Islamic Republic of).

Ramon JM, Bruguera E. Real world study to evaluate the effectiveness of varenicline and cognitive-behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6(4):1530–8.

Skelton E, Lum A, Cooper LE, Barnett E, Smith J, Everson A, et al. Addressing smoking in sheltered homelessness with intensive smoking treatment (ASSIST project): A pilot feasibility study of varenicline, combination nicotine replacement therapy and motivational interviewing. Addict Behav. 2022;124:107074 (2gw, 7603486).

Gordon JS, Armin JS, Cunningham JK, Muramoto ML, Christiansen SM, Jacobs TA. Lessons learned in the development and evaluation of RxCoachTM, an mHealth app to increase tobacco cessation medication adherence. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(4):720–7.

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O’Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, et al. A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Sci. 2017;12(1):1–18.

Prajapati AR, Dima A, Mosa G, Scott S, Song F, Wilson J, et al. Mapping modifiable determinants of medication adherence in bipolar disorder (BD) to the theoretical domains framework (TDF): a systematic review. Psychol Med. 2021;51(7):1082–98.

Mersha AG, Gould GS, Bovill M, Eftekhari P. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to nicotine replacement therapy: a systematic review and analysis using the capability, opportunity, motivation, and behaviour (COM-B) Model. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(23):8895.

Vallis M, Jin S, Klimek-Abercrombie A, Bunko A, Kukaswadia A, Neish CS, et al. Understanding strategies to improve medication adherence among persons with type 2 diabetes: A scoping review. Diabet Med. 2023;40(1): e14941.

Crayton E, Fahey M, Ashworth M, Besser SJ, Weinman J, Wright AJ. Psychological determinants of medication adherence in stroke survivors: a systematic review of observational studies. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(6):833–45.

Easthall C, Taylor N, Bhattacharya D. Barriers to medication adherence in patients prescribed medicines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease: a conceptual framework. Int J Pharm Pract. 2019;27(3):223–31.

Rahman M, Judah G, Murphy D, Garfield SF. Which domains of the theoretical domains framework should be targeted in interventions to increase adherence to antihypertensives? Syst Rev J Hypertens. 2022;40(5):853–9.

Allemann SS, Nieuwlaat R, van den Bemt BJF, Hersberger KE, Arnet I. Matching adherence interventions to patient determinants using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:429.

Adewuya AO, Afolabi MO, Ola BA, Ogundele OA, Ajibare AO, Oladipo BF, et al. The effect of psychological distress on medication adherence in persons with HIV infection in Nigeria. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(1):68–73.

Milam JE, Richardson JL, Marks G, Kemper CA, Mccutchan AJ. The roles of dispositional optimism and pessimism in hiv disease progression. Psychol Health. 2004;19(2):167–81.

Reach G, Benarbia L, Benhamou PY, Delemer B, Dubois S, Gouet D, et al. An unsafe/safe typology in people with type 2 diabetes: bridging patients’ expectations, personality traits, medication adherence, and clinical outcomes. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2022;16:1333–50.

Kahwati L, Viswanathan M, Golin CE, Kane H, Lewis M, Jacobs S. Identifying configurations of behavior change techniques in effective medication adherence interventions: a qualitative comparative analysis. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):83.

Armitage LC, Kassavou A, Sutton S. Do mobile device apps designed to support medication adherence demonstrate efficacy? A systematic review of randomised controlled trials, with meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2020;10(1):e032045.

Long H, Bartlett YK, Farmer AJ, French DP. Identifying brief message content for interventions delivered via mobile devices to improve medication adherence in people with type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Rapid Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res. 2019;21(1):e10421.

Minian N, Mehra K, Rose J, Veldhuizen S, Zawertailo L, Ratto M, et al. Cocreation of a conversational agent to help patients adhere to their varenicline treatment: A study protocol. DIGITAL HEALTH. 2023;1(9):20552076231182810.

Minian N, Mehra K, Earle M, Hafuth S, Ting-A-Kee R, Rose J, et al. AI conversational agent to improve Varenicline Adherence: protocol for a mixed methods feasibility study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023;12(1):e53556.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank: Passang Regyal for her help with data extraction and quality assessment.

Funding

This research is funded by a Proof of Concept Intervention Grant in Primary Prevention of Cancer (Action Grant) of the Canadian Cancer Society and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research-Institute for Cancer Research (grant #707218) and a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Project Grant: Funding Reference Number: PJT 180405.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NM conceived the study and secured funding. NM and MW designed and supervised the study. The search strategy was further developed and executed by TR. MW, SH, AR, DG, NM conducted the data extraction and quality assessment, and MW and NM conducted the data analysis and significantly contributed to the manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors of this paper declare that ethical approval was not required for this review article. This research is a rapid review of primary studies and therefore did not require ethical approval as it did not involve human or animal participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Minian, N., Wong, M., Hafuth, S. et al. Identifying determinants of varenicline adherence using the Theoretical Domains framework: a rapid review. BMC Public Health 24, 679 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18139-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18139-z