Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic had socioeconomic effects in Africa. This study assessed the social and economic determinants of healthcare utilization during the first wave of COVID-19 among adults in Ghana.

Methods

Information about individuals residing in Ghana was derived from a survey conducted across multiple countries, aiming to evaluate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health and overall well-being of adults aged 18 and above. The dependent variable for the study was healthcare utilization (categorized as low or high). The independent variables were economic (such as financial loss, job loss, diminished wages, investment/retirement setbacks, and non-refunded travel cancellations) and social (including food scarcity, loss of financial support sources, housing instability, challenges affording food, clothing, shelter, electricity, utilities, and increased caregiving responsibilities for partners) determinants of health. A multinomial logistic regression was conducted to identify factors associated with healthcare utilization after adjusting for confounders (age, gender, access to medical insurance, COVID-19 status, educational background, employment, and marital status of the participants).

Results

The analysis included 364 responses. Individuals who encountered a loss of financial support (AOR: 9.58; 95% CI: 3.44–26.73; p < 0.001), a decrease or loss of wages (AOR: 7.44, 95% CI: 3.05–18.16, p < 0.001), experienced investment or retirement setbacks (AOR: 10.69, 95% CI: 2.60-43.88, p = 0.001), and expressed concerns about potential food shortages (AOR: 6.85, 95% CI: 2.49–18.84, p < 0.001) exhibited significantly higher odds of low healthcare utilization during the initial phase of the pandemic. Contrastingly, participants facing challenges in paying for basic needs demonstrated lower odds of low healthcare utilization compared to those who found it easy to cover basic expenses (AOR: 0.19, 95% CI: 0.06–0.67, p = 0.001).

Conclusion

Economic and social factors were associated with low healthcare utilization in Ghana during the first wave of the pandemic. Investment or retirement loss and financial support loss during the pandemic had the largest effect on healthcare utilization. Further research is needed to understand the connection between concerns about food shortages, welfare losses during pandemics and healthcare utilization during pandemics in Ghana.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic since its eruption in 2019 has had diverse social and economic impacts across the globe particularly in Africa [1, 2]. The COVID-19 pandemic has led to the disruption of the health system in Africa which is already weaker as compared to the healthcare systems in the global north. For instance, essential services related to HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and maternal and child health have faced significant disruptions in Africa [3,4,5]. The economic and financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Africa has been substantial, leading to a rise in poverty rates, heightened food insecurity, a decline in projected Gross Domestic Product, and a reversal of economic growth across most African nations [6]. This global crisis resulted in approximately one-third of workers losing their jobs, while two-thirds experienced a notable decrease in income ranging from 11.5 to 15.6% in 15 African countries [3]. These economic challenges have exacerbated the difficulties individuals face in accessing healthcare, a situation further complicated by the increased strain on health systems induced by the pandemic [6]. In response to these shocks, health systems underwent transformative changes aimed at saving lives and minimizing mortality rates [7, 8].

In Ghana, the government’s implementation of COVID-19 prevention measures during the initial two months of the pandemic led to disruptions in business operations, resulting in job cuts and losses [9]. Concurrently, the government increased spending to absorb economic shocks and address the social and economic needs of its citizens [10]. The populace also faced challenges related to delayed or limited access to health services, including access to antiretroviral therapy, newborn care diagnosis, and dental care services [11,12,13,14]. Additionally, Ghana had to manage a local outbreak of cerebrospinal meningitis [15].

While existing research acknowledges the negative impact of the pandemic on healthcare access in Ghana [16,17,18,19], there is limited understanding of the behavioral and socioecological determinants influenced by social and economic forces in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Building on previous studies that explored how socioecological factors shape healthcare utilization [20], this study emphasizes that an individual’s ability to seek and utilize healthcare during the pandemic is influenced by individual behavior and socioecological factors. Health behaviors, including healthcare-seeking, are intricately linked to beliefs and attitudes [20]. The study investigates economic and social determinants associated with healthcare utilization during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic among adults in Ghana.

Considering the severity of the pandemic and the implemented preventive measures such as lockdowns, social distancing, handwashing, and face mask usage, and guided by the socioecological model (SEM) of health behavior [20,21,22], the hypothesis posits that individuals facing significant social and economic losses amid the pandemic are less likely to utilize healthcare services. The study employed a behavioral and socioecological model to examine how social and economic factors shape population-level perceptions and access to healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic. The model emphasizes the dual role of financial insecurity as both an economic and social determinant of health and well-being, with potential repercussions on mortality rates and mental health, particularly among vulnerable groups. This approach is crucial as pandemics often prompt immediate investments to mitigate immediate mortality and morbidity outcomes, overlooking the broader determinants of health that persist beyond the pandemic’s duration.

Methods

Ethical approval

Approval for the online data collection in this study was granted by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Institute of Public Health, Obafemi Awolowo University, Ile-Ife, Nigeria (HREC No: IPHOAU/12/1557). Before engaging in the study, participants granted their consent by checking a designated box at the outset of the online survey.

Design

This study was a cross-sectional study using a quantitative data collection approach. An online survey link was generated on the Survey Monkey® platform for the data collection.

Sample size estimation

At the time of conducting the survey, there was a paucity of published evidence regarding the prevalence of healthcare utilization among specific groups or the general adult population in Ghana. To determine the required sample size, we employed the Cochrane formula [23]. Assuming a prevalence (p) of 0.5 for utilizing health care services during the first wave of the pandemic in Ghana, a 95% confidence level, and a margin of error of 0.0515, a sample size of 362 participants was deemed necessary. During survey administration, 364 individuals responded.

Study participants’ recruitment

The survey started in July 2020 and ended in December 2020. The survey targeted individuals aged 18 years and above. For the recruitment process, we utilized non-probability respondent-driven sampling approaches. An online survey link was generated on the Survey Monkey® platform and disseminated to eligible participants. Initial contacts were encouraged to widely share the survey links within their networks, leveraging various social media platforms (Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and WhatsApp) and email listservs. Detailed information on the study methodology has been previously reported in several publications [24,25,26,27].

Data collection tool

Information was gathered using a standardized questionnaire that has been validated for global applicability [28]. The survey tool exhibited a commendable overall content validity index of 0.83. To prevent duplicate submissions, each respondent could participate only once, monitored by their unique internet protocol address. However, respondents had the flexibility to review and modify their answers to the questions before final submission. It’s important to note that there was no obligation for respondents to answer every question, allowing for voluntary participation.

Independent variables

Economic determinants

A series of five questions were employed to assess the economic factors related to COVID-19. Respondents were queried about the financial repercussions they faced due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They were provided with options to mark any applicable losses from the listed categories, including “loss of other sources of financial support,” “job loss or laid off,” “lost or reduced wages,” “investment/retirement loss,” and “travel-related cancellations that were not refunded.” The coding system assigned “0” when a response was not chosen and “1” when a response was selected. The set of questions demonstrated an internal consistency reliability with a Cronbach alpha score of 0.579.

Social determinants

Responses to a cluster of five questions were extracted from the database we designed for the online survey (Monkey® platform) and scrutinized to evaluate the social indicators amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Respondents were queried with the question: “Has the COVID-19 pandemic led to any of the following?” They were provided with the option to indicate ‘yes’ or ‘no’ to specific circumstances, including “loss of food,” “loss of sources of financial support,” “loss of housing,” “difficulty paying for basic needs (food, clothing, shelter, electricity, utilities),” and “the need to spend more time taking care of partners.” Responses were coded as “0” for ‘no’ and “1” for ‘yes.’ The set of questions in this section exhibited high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.832.

Dependent variable

Effect of social and economic determinants on healthcare utilization during the pandemic

A set of three questions was employed to gauge healthcare utilization during the pandemic. Respondents were presented with the query: “Has the COVID-19 pandemic led to any of the following?” The individual response questions included “unable to attend a healthcare provider’s appointment,” “unable to obtain medications that you take,” and “unable to afford medical care.” Responses were coded as “0” for ‘No’ and “1” for ‘Yes.’ A composite variable termed “effect of the pandemic on health care utilization” was derived and coded as “0, 1, 2 and 3.” For binary categorization for the responses, scores equal to or greater than the median were categorized as high healthcare utilization during the pandemic, while scores below the median were classified as low healthcare utilization during the pandemic. The set of questions in this section demonstrated strong internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s alpha score of 0.940.

Confounders

These comprised demographic variables: “age at last birthday,” “sex at birth (male, female),” “highest educational level (secondary, university, and postgraduate),” “employment status (unemployed, employed, student, retired),” “marital status (single, married, others [divorced or widowed]),” and “have medical health insurance (yes, no).” Additionally, the COVID-19 status may influence the utilization of health care services. The participants’ COVID-19 status was assessed through the following questions: “had a COVID-19 test, and the test was positive,” “experienced COVID-19 symptoms but did not test,” and “had a relative or close friend who tested positive for COVID-19”.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using STATA version 16.0®. Frequencies and percentages for all variables were computed. The Chi-square test assessed associations between binary dependent (healthcare utilization) and independent variables such as socio-demographic (age, employment status, marital status, educational level etc.) COVID-19 status (tested positive for COVID-19), social and economic determinants (job loss or laying off, lost or reduced wages, investment/ retirement loss). Multinomial logistic regression gauged the strength of the association between the outcome and predictor variables, adjusting for confounding variables. The significance level was established at α < 0.05.

Results

Participants’ sociodemographic profile and COVID-19 experiences

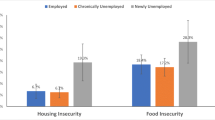

Table 1 shows that the respondents, numbering 364, had a mean (standard deviation) age of 31.6 (7.6) years, with 193 (53.0%) being male. COVID-19 positivity was reported by 18 participants (4.9%), while 22 (6.0%) faced job loss or layoffs, 65 (17.9%) experienced wage reduction or loss, 35 (9.6%) encountered investment/retirement loss, and 37 (10.2%) incurred losses from cancelled travel. Furthermore, 135 (37.1%) participants lost some financial support, 128 (35.2%) expressed concerns about potential food shortages, 8 (2.2%) experienced homelessness, and 97 (26.6%) struggled with paying for basic needs. A significant association was found between lost or reduced wages (p-value < 0.001), worry about food runouts (p-value < 0.001), loss of a source of financial support (p-value < 0.001) and difficulty paying for basic needs (p-value < 0.001) of the respondents and the healthcare utilization.

Table 2 shows that participants experiencing reduced or lost wages (AOR: 7.44, 95% CI: 3.05–18.16, p < 0.001), investment/retirement losses (AOR: 10.69, 95% CI: 2.60-43.88, p = 0.001), concerns about food shortages (AOR: 6.85, 95% CI: 2.49–18.84, p < 0.001), and loss of financial support (AOR: 9.58, 95% CI: 3.44–26.73, p < 0.001) exhibited significantly higher odds of low healthcare utilization during the first wave of the pandemic. In contrast, participants facing difficulties in paying for basic needs demonstrated lower odds of low healthcare utilization compared to those not encountering such challenges (AOR: 0.19, 95% CI: 0.06–0.67, p = 0.001).

Discussion

This study identified that encountering financial losses and facing the risk of food shortages significantly increased the likelihood of low healthcare utilization by 6.85 times during the COVID-19 pandemic. Conversely, participants experiencing difficulties in paying for basic needs demonstrated lower odds of low healthcare utilization during the pandemic. Predictive social factors such as lost or reduced wages and investment/retirement loss significantly heightened the odds of low healthcare utilization. These findings underscore the profound impact of broader economic and social determinants, such as financial losses and food scarcity, on individual access to and utilization of healthcare during the pandemic. Vulnerable individuals and those with lower socioeconomic status may have been disproportionately affected, facing challenges in accessing and utilizing healthcare services in Ghana during the pandemic.

We have established that financial insecurity acts as both an economic and social determinant influencing health and well-being. Specifically, experiences such as lost or reduced wages, investment/retirement loss, and loss of financial support during the pandemic were associated with an increased likelihood of low healthcare utilization among participants. In Ghana, instances of reduced wages [29], livelihood threats [30], and widespread job, financial, and investment losses [31] were frequently reported during the pandemic, driven by stay-at-home orders and business closures. Given that the private sector employs a significant proportion of permanent and temporary workers in Ghana [32], the pandemic’s disruptions to supply and demand chains resulted in extensive layoffs [33].

Our study findings underscore a pattern consistent with previous reports on global [34] and sub-Saharan African [35] levels, highlighting how financial insecurity exacerbates disparities in healthcare utilization in Ghana. Health needs can shift and escalate during pandemics [36, 37], and the inability to address underlying social and economic forces may contribute to reduced healthcare utilization. This has critical implications for population health, especially in communities already grappling with a substantial disease burden, potentially leading to a significant increase in mortality rates [38]. Moreover, it can impact the mental health and well-being of populations particularly vulnerable groups [39].

In a country like Ghana, where individual and household healthcare needs are primarily financed through out-of-pocket payments [40], the repercussions of financial losses such as lost or reduced wages and investment/retirement loss are significant for healthcare utilization [31]. This is directly tied to one’s capacity to afford and access healthcare services. Our study furnishes evidence suggesting that individuals experiencing financial insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic may have encountered unmet healthcare needs. Although cash transfer schemes were introduced in Ghana during the pandemic by the Government to provide relief to small-scale businesses [41], their effectiveness in mitigating the impact of extensive layoffs by businesses remains unverified. Conducting empirical studies on catastrophic expenditures and welfare loss during and post-COVID-19 could offer valuable insights into how financial losses influenced healthcare utilization in Ghana.

The potential threat of financial insecurity, as highlighted in this study, may also be associated with a social risk factor contributing to the observed low utilization of healthcare during the COVID-19 pandemic and difficulty in paying for basic needs. The inability to afford necessities signifies a lack of purchasing power for individuals and households, hindering their ability to meet crucial medical healthcare needs during the pandemic. This situation may arise from financial challenges faced by individuals and households amid the pandemic. As a result, it becomes crucial to incorporate efforts to reduce financial losses into the priority-setting for pandemic response. These efforts could involve enhancing primary healthcare outreach programs, especially targeting communities that are disproportionately affected by financial insecurity.

Moreover, the results of the study reveal an association between the perception of food insecurity, specifically concerns about food stock depletion during the pandemic and low healthcare utilization among adult Ghanaians. A previous study suggested that food insecurity serves as a proxy measure for financial insecurity [42]. Consequently, the linkage between food insecurity and reduced healthcare utilization during the pandemic may be explained by underlying financial insecurity. These findings align with previous research indicating that food insecurity, stemming from economic and livelihood disruptions during the COVID-19 pandemic, correlates with adverse health outcomes [40, 41, 43].

The challenges posed by the pandemic, encompassing social, environmental, and ecological factors, contribute to a surge in food prices due to disruptions in the global food supply chain [44]. Consequently, individuals and households may prioritize spending on food over healthcare during the pandemic when resources are scarce. Further empirical studies are essential to comprehensively grasp the connection between concerns about food stock depletion and healthcare utilization during the COVID-19 pandemic, providing valuable insights for long-term health planning purposes.

Strengths and weaknesses

One strength of this study lies in the diverse geographical distribution of participants across different residential locations in Ghana. The wide geographical distribution of participants has facilitated an understanding of the national impact of both social and economic determinants on healthcare utilization during the initial wave of the pandemic. Existing evidence published during this phase is scarce and often constrained in geographical scope [13, 30, 42, 45]. Although this study boasts a broader geographic representation, it is imperative to acknowledge that this study also has some limitations. For instance, the use of the convenience sampling method could have unintentionally excluded individuals lacking smartphones, internet access, or English proficiency from the study. This limitation hinders the generalizability of the study findings. Additionally, being a cross-sectional study, this study could not confidently establish causal relationships between the variables that were studied. Despite these inherent limitations, the study offers valuable insights that can inform pandemic response guidelines in the future.

This study, employing the socioecological model of health behavior, highlights the significant influence of broader economic and social determinants on individual healthcare access and utilization during the pandemic, with vulnerable populations and those of lower socioeconomic status disproportionately affected. It emphasizes the dual role of financial insecurity as both an economic and social determinant of health and well-being, with potential repercussions on mortality rates and mental health, particularly among vulnerable groups. In a context like Ghana, where out-of-pocket payments dominate healthcare financing, financial losses have profound implications for healthcare utilization. Efforts to address these challenges should be integrated into pandemic response priorities, including targeted outreach programs and initiatives to reduce financial losses. The study also underscores the association between food insecurity and reduced healthcare utilization, emphasizing the need for further empirical studies to elucidate this connection for effective long-term health planning.

Conclusion

The first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the pre-existing limited healthcare utilization in Ghana. Factors such as financial loss, reduced wages, investment loss, concerns about food shortages, and challenges in affording basic needs were predictive of decreased healthcare utilization among Ghanaian adults during the pandemic. These results underscore the significance of addressing financial and food insecurity during health emergencies, emphasizing the necessity for comprehensive national policies ensuring social, economic, and financial inclusion in pandemic control efforts. Further research is warranted to delve into the interplay between food shortages and welfare losses during the pandemic and their influence on healthcare utilization in Ghana.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

Adjusted Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

References

Adu-Gyamfi S, Brenya E, Gyasi RM, Abass K, Darkwa BD, Nimoh M, Tomdi L. A COVID in the wheels of the world: a contemporary history of a pandemic in Africa. Res Globalization. 2021;3:100043.

Mhlanga D, Ndhlovu E. Socio-economic implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on smallholder livelihoods in Zimbabwe.2020.

Holtz L. COVID-19’s impact on overall health care services in Africa (brookings.edu) Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/blog/africa-in-focus/2021/10/12/covid-19s-impact-on-overall-health-care-services-in-africa/, 2021 on 08/11/2023/.

Folayan MO, Arije O, Enemo A, Sunday A, Muhammad A, Nyako HY, Abdullah RM, Okiwu H, Undelikwo VA, Ogbozor PA, Amusan O, Alaba OA, Lamontagne E. Factors associated with poor access to HIV and sexual and reproductive health services in Nigeria for women and girls living with HIV during the COVID-19 pandemic. Afr J AIDS Res. 2022;21(2):171–82.

Assefa N, Sié A, Wang D, Korte ML, Hemler EC, Abdullahi YY, Lankoande B, Millogo O, Chukwu A, Workneh F, Kanki P. Reported barriers to healthcare access and service disruptions caused by COVID-19 in Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, and Nigeria: a telephone survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2021;105(2):323.

Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). COVID-19 and Africa: Socio-economic implications and policy responses. 2020. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/oecd-policy-responses-to-coronavirus-covid-19_5b0fd8cd-en/dateasc?page=3 on 08/11/2023.

Osei SA, Biney RP, Anning AS, Nortey LN, Ghartey-Kwansah G. Low incidence of COVID-19 case severity and mortality in Africa; could malaria co-infection provide the missing link? BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):1–1.

Lawal Y. Africa’s low COVID-19 mortality rate: a paradox? Int J Infect Dis. 2021;102:118–22.

Aduhene DT, Osei-Assibey E. Socio-economic impact of COVID-19 on Ghana’s economy: challenges and prospects. Int J Soc Econ. 2021;48(4):543–56.

Dzigbede KD, Pathak R. COVID-19 economic shocks and fiscal policy options for Ghana. J Public Budg Acc Financial Manage. 2020;32(5):903–17.

Morgan AK, Awafo BA. Lessons for averting the delayed and reduced patronage of non-COVID-19 medical services by older people in Ghana. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2020;63(6–7):728–31.

Abraham SA, Berchie GO, Doe PF, Agyare E, Addo SA, Obiri-Yeboah D. Effects of COVID-19 pandemic on ART Service delivery: perspectives of healthcare workers in a Teaching Hospital in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–0.

Abdul-Mumin A, Cotache-Condor C, Bimpong KA, Grimm A, Kpiniong MJ, Yakubu RC, Kwarteng PG, Fuseini YH, Smith ER. Decrease in admissions and change in the diagnostic landscape in a newborn care unit in northern Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Pead. 2021;9:642508.

Hewlett SA, Blankson PK, Konadu AB, Osei-Tutu K, Aprese D, Adjei M, Yawson AE, Donkor P, Nyako EA. COVID-19 pandemic and dental practice in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2020;54(4s):100–3.

Karpati J, Elezaj E, Cebotari V, de Neubourg C. Primary and secondary impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children in Ghana. 2020. https://orbilu.uni.lu/bitstream/10993/46437/1/UNICEF%202021.pdf. Accessed on 07/12/2023.

Ofori AA, Osarfo J, Agbeno EK, Manu DO, Amoah E. Psychological impact of COVID-19 on health workers in Ghana: a multicentre, cross-sectional study. SAGE open Medicine. 2021;9:20503121211000919.

Amewu S, Asante S, Pauw K, Thurlow J. The economic costs of COVID-19 in sub-saharan Africa: insights from a simulation exercise for Ghana. Eur J Dev Res. 2020;32(5):1353–78.

Abor PA, Abor JY. Implications of COVID-19 pandemic for health financing system in Ghana. J Health Manage. 2020;22(4):559–69.

Mensah D, Asampong R, Amuna P, Ayanore MA. COVID-19 effects on national health system response to a local epidemic: the case of cerebrospinal meningitis outbreak in Ghana. Pan Afr Med J. 2020;35(Suppl 2).

Ngwenya N, Nkosi B, Mchunu LS, Ferguson J, Seeley J, Doyle AM. Behavioural and socio-ecological factors that influence access and utilization of health services by young people living in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: implications for intervention. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231080.

Olaniyan A, Isiguzo C, Hawk M. The Socioecological Model as a framework for exploring factors influencing childhood immunization uptake in Lagos state, Nigeria. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–0.

Garney W, Wilson K, Ajayi KV, Panjwani S, Love SM, Flores S, Garcia K, Esquivel C. Social-ecological barriers to access to healthcare for adolescents: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4138.

Cochran WG. (1977) Sampling Techniques. 3rd Edition, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Ellakany P, Zuñiga RA, El Tantawi M, Brown B, Aly NM, Ezechi O, Uzochukwu B, Abeldaño GF, Ara E, Ayanore MA, Gaffar B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on student sleep patterns, sexual activity, screen use, and food intake: a global survey. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(1):e0262617.

Folayan MO, Ibigbami O, Brown B, El Tantawi M, Uzochukwu B, Ezechi OC, Aly NM, Abeldaño GF, Ara E, Ayanore MA, Ayoola OO. Differences in COVID-19 preventive behavior and food insecurity by HIV status in Nigeria. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(3):739–51.

Folayan MO, Ibigbami O, ElTantawi M, Abeldaño GF, Ara E, Ayanore MA, Ellakany P, Gaffar B, Al-Khanati NM, Idigbe I, Ishabiyi AO. Factors associated with COVID-19 pandemic induced post-traumatic stress symptoms among adults living with and without HIV in Nigeria: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):48.

Folayan MO, Ibigbami O, El Tantawi M, Brown B, Aly NM, Ezechi O, Abeldaño GF, Ara E, Ayanore MA, Ellakany P, Gaffar B. Factors associated with financial security, food security and quality of daily lives of residents in Nigeria during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):7925.

El Tantawi M, Folayan MO, Nguyen AL, Aly NM, Ezechi O, Uzochukwu BS, Alaba OA, Brown B. Validation of a COVID-19 mental health and wellness survey questionnaire. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1509.

Afriyie DK, Asare GA, Amponsah SK, Godman B. COVID-19 pandemic in resource-poor countries: challenges, experiences and opportunities in Ghana. J Infect Developing Ctries. 2020;14(08):838–43.

Asiamah N, Opuni FF, Mends-Brew E, Mensah SW, Mensah HK, Quansah F. Short-term changes in behaviors resulting from COVID-19-related social isolation and their influences on mental health in Ghana. Commun Ment Health J. 2021;57(1):79–92.

Olczyk M, Kuc-Czarnecka ME. Determinants of COVID-19 impact on the private sector: a multi-country analysis based on survey data. Energies. 2021;14(14):4155.

Asante LA, Mills RO. Exploring the socio-economic impact of COVID-19 pandemic in marketplaces in urban Ghana. Afr Spectr. 2020;55(2):170–81.

Amu H, Dickson KS, Adde KS, Kissah-Korsah K, Darteh EK, Kumi-Kyereme A. Prevalence and factors associated with health insurance coverage in urban sub-saharan Africa: multilevel analyses of demographic and health survey data. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(3):e0264162.

Antwi J, Abbey C, Ogbey P, Ofori R. Policy responses to fight COVID-19; the case of Ghana. Revista De Administração Pública. 2021;55:122–39.

Baah-Boateng W. Copyright© 2015 Ghana Statistical Service. Retrieved from https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/NATIONAL%20EMPLOYMENT%20REPORT_FINAL%20%2024-5-16.pdf on 10/12/2023.

Panchal N, Kamal R, Orgera K, Cox C, Garfield R, Hamel L, Chidambaram P. The implications of COVID-19 for mental health and substance use. Kaiser family foundation. 2020;21. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/the-implications-of-covid-19-for-mental-health-and-substance-use/ 16/11/2023.

Shadmi E, Chen Y, Dourado I, Faran-Perach I, Furler J, Hangoma P, Hanvoravongchai P, Obando C, Petrosyan V, Rao KD, Ruano AL. Health equity and COVID-19: global perspectives. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):1–6.

Muscatello DJ, Cretikos MA, MacIntyre CR. All-cause mortality during first wave of pandemic (H1N1) 2009, New South Wales, Australia, 2009. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16(9):1396.

Abdul-Mumin A, Cotache-Condor C, Bimpong KA, Grimm A, Kpiniong MJ, Yakubu RC, Kwarteng PG, Fuseini YH, Smith ER. Decrease in admissions and change in the diagnostic landscape in a newborn care unit in northern Ghana during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Pead. 2021;9.

Saah FI, Amu H, Seidu AA, Bain LE. Health knowledge and care-seeking behaviour in resource-limited settings amidst the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(5):e0250940.

Leddy AM, Weiser SD, Palar K, Seligman H. A conceptual model for understanding the rapid COVID–19–related increase in food insecurity and its impact on health and healthcare. Am J Clin Nutr. 2020;112(5):1162–9.

Niles MT, Wirkkala KB, Belarmino EH, Bertmann F. Home food procurement impacts food security and diet quality during COVID-19. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1–5.

Nekmahmud M. Food consumption behavior, food supply chain disruption, and food security crisis during the COVID-19: the mediating effect of food price and food stress. J Foodserv Bus Res 2022 Jun 30:1–27.

Stub T, Jong MC, Kristoffersen AE. The impact of COVID-19 on complementary and alternative medicine providers: a cross-sectional survey in Norway. Adv Integr Med. 2021;8(4):247–55.

Nayak A, Islam SJ, Mehta A, Ko YA, Patel SA, Goyal A, Sullivan S, Lewis TT, Vaccarino V, Morris AA, Quyyumi AA. Impact of social vulnerability on COVID-19 incidence and outcomes in the United States. MedRxiv. 2020 Apr 14:2020–04.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate all the participants who provided data and contributed their time to make this study possible.

Funding

The authors provided personal funds to conduct this study. A.L.N. was supported by a grant from the NIH/NIA (K01 AG064986-01).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.A.A conceived the study. Data analysis was conducted by M.A. and M.A.A. PA and MOF made inputs to the initial results and analysis. P.A., M.E.T, O.E., B.B., B.U., N.M.A., A. L. N., B.G., M.F.A.Q., B.O.P., A.O.I., P.E., M.A.Y., J.I.V., and F.B.L. all read the draft manuscript and made inputs prior to the final draft. All authors approved the final manuscript for submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval of the current study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee at the Institute of Public Health of the Obafemi Awolowo University Ile-Ife, Nigeria (HREC No: IPHOAU/12/1557) as the lead partner for this study. The protocol was by international and national research guidelines. All participants provided informed consent before taking the survey.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Martin Ayanore is an Associate Editor, at BMC Public Health while Morenike Oluwatoyin Folayan and Maha El Tantawi are Senior Board Members with BMC Oral Health. Jorma Virtanen is an Associate Editor, at BMC Oral Health. All other authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ayanore, M.A., Adjuik, M., Zuñiga, R.A.A. et al. Economic and social determinants of health care utilization during the first wave of COVID-19 pandemic among adults in Ghana: a population-based cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 24, 455 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17912-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-17912-4