Abstract

Background

Physical activity is important for all aspects of health, yet most university students are not active enough to reap these benefits. Understanding the factors that influence physical activity in the context of behaviour change theory is valuable to inform the development of effective evidence-based interventions to increase university students’ physical activity. The current systematic review a) identified barriers and facilitators to university students’ physical activity, b) mapped these factors to the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) and COM-B model, and c) ranked the relative importance of TDF domains.

Methods

Data synthesis included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research published between 01.01.2010—15.03.2023. Four databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, SPORTDiscus, and Scopus) were searched to identify publications on the barriers/facilitators to university students' physical activity. Data regarding study design and key findings (i.e., participant quotes, qualitative theme descriptions, and survey results) were extracted. Framework analysis was used to code barriers/facilitators to the TDF and COM-B model. Within each TDF domain, thematic analysis was used to group similar barriers/facilitators into descriptive theme labels. TDF domains were ranked by relative importance based on frequency, elaboration, and evidence of mixed barriers/facilitators.

Results

Thirty-nine studies involving 17,771 participants met the inclusion criteria. Fifty-six barriers and facilitators mapping to twelve TDF domains and the COM-B model were identified as relevant to students’ physical activity. Three TDF domains, environmental context and resources (e.g., time constraints), social influences (e.g., exercising with others), and goals (e.g., prioritisation of physical activity) were judged to be of greatest relative importance (identified in > 50% of studies). TDF domains of lower relative importance were intentions, reinforcement, emotion, beliefs about consequences, knowledge, physical skills, beliefs about capabilities, cognitive and interpersonal skills, social/professional role and identity, and behavioural regulation. No barriers/facilitators relating to the TDF domains of memory, attention and decision process, or optimism were identified.

Conclusions

The current findings provide a foundation to enhance the development of theory and evidence informed interventions to support university students’ engagement in physical activity. Interventions that include a focus on the TDF domains 'environmental context and resources,' 'social influences,' and 'goals,' hold particular promise for promoting active student lifestyles.

Trial registration

Prospero ID—CRD42021242170.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Physical activity (PA) has a powerful positive impact on all aspects of health. Regular PA can prevent and treat noncommunicable diseases [1, 2], build resilience against the development of mental illness [3], and attenuate cognitive decline [4]. Given these pervasive health benefits, increasing participation in PA is recognised as a global priority by international public health organisations. Indeed, a core aspect of the World Health Organisation’s action plan for a “healthier world” is to achieve a 15% reduction in the global prevalence of physical inactivity by 2030 [5].

Despite international efforts to reduce physical inactivity, university students frequently do not meet the recommended level of PA required to attain its health benefits. Approximately 40–50% of university students are physically inactive [6], many of whom attribute their inactivity to unique challenges associated with university life. For many students, the transition to university coincides with new academic, social, financial, and personal responsibilities [7], disrupting established routines and imposing additional barriers to the initiation or maintenance of healthy lifestyle habits such as regular PA [8]. Students’ PA tends to decline further during periods of high stress and academic pressure, such as exams and assignment deadlines [9]. This pattern has been observed across diverse university populations and cultural contexts [10,11,12], highlighting the importance of understanding the factors that contribute to physical inactivity among this cohort globally.

Understanding the barriers and facilitators to PA in the context of the university setting is an important step in developing effective, targeted interventions to promote active lifestyles among university students. A recently published systematic review found that lack of time, motivation, access to places to practice PA, and financial resources were primary barriers to PA for undergraduate university students [13]. A corresponding and complementary synthesis of the facilitators of PA, however, has not yet been conducted. Such a synthesis would be valuable in enabling a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence students' PA and identifying facilitators that could be leveraged in intervention design. Furthermore, applying theoretical frameworks to understand barriers and facilitators to PA can guide the development of theory-informed, evidence-based interventions for university students that purposely and effectively target factors that influence their participation in PA.

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [14,15,16] and the COM-B model of behaviour [17] are two robust, gold-standard frameworks frequently used to examine the determinants of human behaviour. The TDF is an integrated framework of 14 theoretical domains (see Additional file 1 for domains, definitions, and constructs) which provide a comprehensive understanding of the key factors driving behaviour. The TDF was developed through expert consensus, synthesising 33 psychological theories (such as social cognitive theory [18, 19] and the theory of planned behaviour [20, 21] and 128 theoretical constructs (such as ‘competence’, ‘goal priority’, etc.) across disciplines identified as most relevant to the implementation of behaviour change interventions. Identifying the relative importance of theoretical domains allows intervention designers to triage which behaviour change strategies should be prioritised in intervention development [22, 23]. The TDF has been widely applied by researchers and practitioners to systematically identify which theoretical domains are most relevant for understanding health behaviour change and policy implementation across a range of contexts, including education [24], healthcare [25], and workplace environments [26].

The 14 TDF domains map onto the COM-B model (Fig. 1), which is a broader framework for understanding behaviour and provides a direct link to intervention development frameworks. The COM-B model posits that no behaviour will occur without sufficient capability, opportunity, and motivation. Where any of these are lacking, they can be strategically targeted to support increased engagement in a desired behaviour, including participation in PA. Within the COM-B model, capability can be psychological (e.g., knowledge to engage in the necessary processes) or physical (e.g., physical skills); opportunity can be social (e.g., interpersonal influences) or physical (e.g., environmental resources); and motivation can be automatic (e.g., emotional reactions, habits) or reflective (e.g., intentions, beliefs). The COM-B model was developed through a process of theoretical analysis, empirical evidence, and expert consensus as a central part of a broader framework for developing behaviour change interventions known as the Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) [17].

The TDF domains linked to the COM-B model subcomponents

Note. Reproduced from Atkins, L., Francis, J., Islam, R., et al. (2017) A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science 12, 77. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

Using the TDF and COM-B model to understand the barriers and facilitators to university students’ participation in PA is valuable to inform the development of effective evidence-based interventions that are tailored to address the most influential determinants of behaviour change. As such, this systematic review aimed to: a) identify barriers and facilitators to university students’ participation in PA; b) map these factors using the TDF and COM-B model; and c) determine the relative importance of each TDF domain.

Methods

Study design

The systematic review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [27]. The review protocol was registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021242170).

Search strategy

Search terms and parameters were developed in collaboration with a Monash University librarian with expertise in systematic review methodology. The following databases were searched on 15.03.2023 to identify relevant literature: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and SPORTDiscus. Key articles were also selected for citation searching via Scopus. In consultation with a librarian, these databases were selected due to their unique scope, relevance, broad coverage, and utility. This process ensured the identified literature aligned with the aim and research topic of our systematic review. A 01.01.2010—15.03.2023 publication period was purposefully specified to account for the significant advancements in digital fitness support and tracking tools within the past decade [28], All available records were searched using the following combination of concepts in the title or abstract of the article: 1) barriers, facilitators, or intervention,Footnote 1 2) physical activity, 3) university, and 4) students. Each search concept was created by first developing a list of search terms relevant to each concept (e.g., for the ‘physical activity’ concept search terms included ‘physical exercise’, ‘physical fitness’, ‘sports’, ‘inactive’, ‘sedentary’, etc.). To create each concept, search terms were then searched collectively using the operator ‘OR’. Each search concept was then combined into the final search by using the operator ‘AND’. Search terms related to concepts 1, 2 and 3 included indexed terms unique and relevant to each database (i.e., Medical Subject Heading Terms for MEDLINE, Index Terms for PsycINFO, and Thesaurus terms for SPORTDiscus). The search was performed according to Boolean operators (e.g., AND, OR) (see Additional file 2 for the complete search syntax for MEDLINE). Unpublished studies were not sought.

Selection criteria

Articles were included if they: (a) reported university students’ self-reported barriers and/or facilitators to physical activity or exerciseFootnote 2; (b) were written in English; and (c) were peer-reviewed journal articles. Articles encompassed studies directly investigating barriers and/or facilitators to students’ participation in PA and physical exercise intervention studies, where the latter reported participants’ self-reported barriers and/or facilitators to intervention adherence (see Table 1 below for full criteria).

Study selection

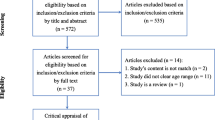

Identified articles were uploaded to EndNote X9 software [30]. A duplication detection tool was used to detect duplicates, which were then screened for accuracy by CB prior to removal. The remaining articles were uploaded to Covidence to enable blind screening and conflict resolution. Articles were screened at the title and abstract level against the inclusion and exclusion criteria by author CB, and 25% were independently screened by BP. The full text of studies meeting the inclusion criteria was then screened against the same criteria by CB, and 25% were again independently screened by BP. Differences were resolved by an independent author (KR). Inter-rater agreement in screening between CB and BP was high (0.96 for title and abstract screening, 0.83 for full-text screening). The decision to dual-screen 25% of studies was strategically chosen to balance thoroughness with efficiency, ensuring both the validity of the screening criteria and the reliability of the primary screener’s decisions. This approach aligns with the protocols used in similar systematic reviews in the field (e.g., [31, 32]).

Data extraction

Key article characteristics were extracted, including the author/s, year of publication, country of origin, participant characteristics (e.g., enrolment status, exercise engagement [if reported]), sample size, research design, methods, and analytical approach. Barriers and facilitators were also extracted for each article and subsequently coded according to the 14 domains of the TDF and six subcomponents of the COM-B model. Quantitative data were only extracted if ≥ 50% of students endorsed a factor as a barrier or facilitator. This cut-off criterion was applied to maintain focus on the most common variables of influence and aligns with other reviews synthesising common barriers and facilitators to behaviour change (e.g., [26, 33]).

A coding manual was developed to guide the process of mapping barriers and facilitators to the TDF and COM-B. All articles were independently coded by at least two authors (CB and BS, BP or KR). The first version of the manual was developed a priori, based on established guides for applying the TDF and COM-B model to investigate barriers and facilitators to behaviour [14, 34], and updated as needed via regular consultation with a co-author and TDF/COM-B designer LA to ensure the accuracy of the data extraction. Barriers and facilitators were only coded to multiple TDF domains if deemed essential to accurately contextualise the core elements of the barrier/facilitator, and when the data in individual papers was described in sufficient detail to indicate that more than one domain was relevant. For example, if ‘lack of time due to competing priorities’ was reported as a barrier to PA, this encompassed both the ‘environmental context and resources’ (i.e., time) and ‘goals’ (i.e., competing priorities) domains of the TDF. Coding conflicts were resolved via discussion with LA.

Data analysis

The following three-step method was utilised to synthesise quantitative and qualitative data:

-

1.

Framework analysis [35] was conducted to deductively code barriers and facilitators onto TDF domains and COM-B subcomponents. This involved identifying barriers and facilitators in each article, extracting and labelling them, and determining their relevance against the definitions of the TDF domains and COM-B subcomponents. This process involved creating tables to assist in the systematic categorisation of barriers and facilitators into relevant TDF domains and COM-B subcomponents.

-

2.

Within each TDF domain, thematic analysis [36] was conducted to group similar barriers and facilitators together and inductively generate summary theme labels.

-

3.

The relative importance of each TDF domain was calculated according to frequency (number of studies), elaboration (number of themes) and the identification of mixed barriers/facilitators regarding whether a theme was a barrier or facilitator within each domain (e.g., if some participants reported that receiving encouragement from their family to exercise was a facilitator, and others reported that lack of encouragement from their family to exercise was a barrier). The rank order was determined first by frequency, then elaboration, and finally by mixed barriers/facilitators.

This methodology follows previous studies using the TDF and COM-B to characterise barriers and facilitators to behaviour change and rank their relative importance [22, 23].

Results

Study characteristics

Following the removal of duplicates, 6,152 articles met the search criteria and were screened based on title and abstract. A total of 5,995 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (see Fig. 2 below for the PRISMA flowchart). After the title and abstract screening, 157 full-text articles were retrieved and assessed for eligibility. One additional article was identified and included following citation searching of selected key articles. Thirty-nine articles met the inclusion criteria (see Additional file 3 for a summary of these studies). Eight studies were conducted in the USA, seven in Canada, three in Germany, two each in Qatar, Spain, the United Arab Emirates, and the United Kingdom, and one each in Australia, Belgium, Columbia, Egypt, Ireland, Japan, Kuwait, Malaysia, New Zealand, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, and Uganda.

Relative importance of TDF domains and COM-B components

Twelve of the 14 TDF domains and all six subcomponents of the COM-B model were identified as relevant to university students' PA. The rank order of relative importance of TDF domains and associated COM-B subcomponents are presented in Table 2. The three most important domains were identified in at least 54% of studies.

Barriers and facilitators to student’s physical activity

Within the TDF domains, 56 total themes were identified, including 26 mixed barriers/facilitators, 18 facilitators and 12 barriers (Table 3). The barriers and facilitators identified within each TDF domain are summarised below (with associated COM-B subcomponent presented in parentheses), in order of relative importance:

-

1. Environmental context and resources (Physical Opportunity) (n = 90% studies)

The most frequent barrier to PA across all TDF domains was ‘lack of time’, most often in the context of study demands. Time constraints were exacerbated by long commutes to university, family responsibilities, involvement in co-curricular activities, and employment commitments. Students’ need for ‘easily accessible exercise options, facilities and equipment’ was a recurring theme. PA was deemed inaccessible if exercise facilities and other infrastructure to support PA, such as bike paths and running trails, were situated too far from the university campus or students’ residences, or if fitness classes were scheduled at inconvenient times. ‘Financial costs’ emerged as a theme. The costs associated with accessing exercise facilities, equipment and programs consistently deterred students from engaging in PA. The desire for ‘safe and enjoyable’, ‘weather appropriate’ environments for PA were frequently reported. Participating in outdoor PA in green spaces or near water increased enjoyment, provided the environment felt safe and weather conditions were suitable for PA. Factors related to students’ home, work, and university environment impacted their participation in ‘incidental PA’. Incidental PA was influenced by whether students engaged in domestic house chores, and manual work, and actively commuted to university and between classes on-campus. Students’ ‘access to a variety of physical activities’ and ‘information provision regarding on-campus exercise options’ impacted their PA. Students most often had access to a wide variety of physical activities, however, it could be difficult to access information about what types of activities were available on-campus and how to sign up to participate. The ‘lack of personalised physical activities to cater to individual fitness needs’ was a barrier, particularly for students with low levels of PA who required beginner-oriented programs. Another barrier was the ‘lack of university policy and promotion to encourage PA’, which led students to perceive that there was no obligation to participate in PA and that the university did not value it. ‘Health-concerning behaviours associated with university’, including poor diet, increased alcohol intake and sedentary behaviour, negatively impacted students’ PA. ‘Listening to music while exercising’ was a facilitator.

-

2. Social influences (Social Opportunity) (n = 72% studies)

Within social influences, ‘exercising with others’ emerged as the most frequent theme. Doing so increased students’ accountability, enjoyment and motivation, and helped them to overcome feelings of intimidation when exercising alone. Having a lack of friends to exercise with was a particular concern for students who were new to exercise or infrequently participated in PA. Receiving ‘encouragement from others to be physically active’, such as family members, friends, peers, and fitness instructors, shaped students’ values toward PA and enhanced their motivation and self-efficacy. Students’ family members, friends and teachers discouraged PA if it was not valued, or in favour of other priorities, such as academic commitments. Another recurrent theme was ‘competition or relative comparison to others’. While most students were motivated by competition, a minority felt demotivated if they compared themselves to others with higher PA standards, especially if they failed to achieve similar PA goals. Sociocultural norms influenced barriers/facilitators to PA across different cultures, and between various groups, such as international versus domestic students, and women versus men. Students from Japan and Hawaii viewed PA as an important part of their culture, in contrast to students from the Philippines who described the opposite. Participation in PA enabled international students to integrate with domestic students and learn about the local culture, however cultural segregation was a barrier to participation in university team sports. For female students from some middle-eastern countries, including Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Qatar, cultural norms made it impermissible for women to engage in PA, particularly compared to men. Religion also differentially impacted barriers/facilitators between women and men. Muslim women reported that Islamic practices, such as needing to engage in PA separately from men, be accompanied by a male family member while going outdoors, or dress modestly, posed additional barriers to PA. However, one study reported that Islamic teachings generally encouraged PA for both women and men by emphasising the importance of maintaining good health. Other gender-specific barriers were identified. Women often felt unwelcome or intimidated by men in exercise facilities, partly due to the perception that these facilities were tailored toward “masculine” sports and/or dominated by men. ‘Being stared at while engaging in PA’ was another barrier, impacting both women and students with a disability. A less common facilitator was the influence of both positive and negative ‘exercise role models’. For example, students practiced PA because they aspired to be like someone who was physically active, or because they did not want to be like someone who was not physically active.

-

3. Goals (Reflective Motivation) (n = 54%)

‘Prioritisation of PA compared to other activities’ was the most common theme within goals. Students frequently prioritised other activities, such as study, social activities, or work, over PA. However, those who played team sports or regularly practiced PA were more inclined to prioritise it for its recognised health benefits (i.e., stress management), and its role in enhancing confidence. Additional facilitators included ‘engaging in PA to achieve an external goal’, such as improving one’s appearance, and ‘setting specific PA-related goals’ as a means to enhance accountability.

-

4. Intentions (Reflective Motivation) (n = 44%)

Within intentions, ‘motivation to engage in PA’ was the most common theme. Students most often noted a lack of self-motivation for PA. Less frequent barriers included perceiving PA as an obligatory or necessary "chore", and ‘failing to follow through on intentions to engage in PA’. Conversely, ‘self-discipline to engage in PA’ emerged as a facilitator that assisted students in maintaining a regular PA routine.

-

5. Reinforcement (Automatic Motivation) (n = 38%)

The most frequent facilitator within reinforcement was ‘experiencing the positive effects of PA’ on their health and wellbeing. These included physical health benefits (i.e., maintaining fitness), psychological benefits (i.e., stress reduction), and cognitive health benefits (i.e., enhanced academic performance). Conversely, barriers arose from ‘experiencing discomfort during or after PA’ due to pain, muscle soreness or fatigue. ‘Past and current habits and routines’ was a theme. Students were more likely to participate in PA if they had established regular exercise routines, and that forming these habits at an early age made it easier to maintain them later in life. However, maintaining a regular PA routine was difficult in the context of inflexible university schedules. Students’ ‘sense of accomplishment in relation to PA’ was a theme. Students were less likely to feel a sense of accomplishment after participating in PA if it was not physically challenging. Consistent facilitators were ‘receiving positive feedback from others’ after engaging in PA, such as compliments, and ‘receiving incentives’, such as reducing the cost of gym memberships if students participated in more PA. ‘Experiencing a sense of achievement’ after reaching a PA-related goal or winning a sports match also served as a facilitator.

-

6. Emotion (Automatic Motivation) (n = 38%)

‘Enjoyment’ was the most frequently cited emotional theme. Most students reported that PA was fun and/or associated with positive feelings, however, a minority described PA as unenjoyable, boring, and repetitive. Students’ ‘poor mental health and negative affectivity’ (such as feeling sad, stressed or self-conscious, as well as fear of injury and pain), adversely impacted their motivation to be physically active.

-

7. Beliefs about consequences (Reflective Motivation) (n = 31%)

‘Beliefs about the physical health consequences of PA’ was the most recurrent barrier/facilitator. Most students understood that PA was essential for maintaining good health and preventing illness. However, some students who rarely or never engaged in PA believed they could delay pursuing an active lifestyle until they were older without compromising their health. Participating in PA to ‘maintain or improve one’s physical appearance’ acted as a facilitator. This motivation was most often cited in contexts such as increasing or decreasing weight, changing body shape or enhancing muscle tone. Beliefs about the positive environmental, occupational and psychological impacts of PA also served as facilitators. Students were motivated to participate in PA due to the environmental benefits of using active transport. They also acknowledged the importance of being physically fit for work and believed that being active was beneficial for mental health. ‘Receiving advice to participate in PA from a credible source’, such as a health professional, further facilitated students’ motivation to be active.

-

8. Knowledge (Psychological Capability) (n = 28%)

'Knowledge about the benefits of PA’, encompassing an understanding of the various types of benefits (i.e., physical, mental, or cognitive) and the biological mechanisms by which PA brings about these changes was identified as the most common knowledge theme. Being aware of these benefits positively influenced students’ motivation to be physically active. Conversely, students’ lack of knowledge about the gym environment and the programs available were barriers to PA. Regarding the gym environment, students’ ‘lack of knowledge about how to navigate through the gym, what exercises to do, and how to use exercise equipment’ amplified feelings of intimidation. Likewise, ‘lack of knowledge about the types of exercise programs and activities that were available on-campus, and how to sign up to participate’ were all barriers. A unique theme emerged concerning ‘knowledge about how to adapt physical activities for students with a disability’. Students with a disability described how fitness instructors often had a limited understanding of how to modify activities to enable them to participate. However, students with a disability were able to overcome this barrier if they possessed their own knowledge about how to tailor physical activities to meet their specific needs.

-

9. Physical skills (Physical Capability) (n = 21%)

The most prevalent theme within physical skills was ‘having the physical skills and fitness to participate in PA’. A lack of physical skills was most frequently a hindrance to PA. Additional obstacles to PA included being physically inhibited due to a ‘lack of energy’ or ‘physical injury’.

-

10. Beliefs about capabilities (Reflective Motivation) (n = 18%)

Within beliefs about capabilities, ‘self-efficacy to participate in PA’ was the most recurrent theme. Students who doubted their success in becoming physically active or who lacked confidence in their ability to initiate PA or participate in sport were less motivated to take part. A less frequent facilitator was students’ ‘self-affirmation to participate in PA’, often referring to positive cognitions about one’s own physical abilities.

-

11. Cognitive and interpersonal skills (Psychological Capability) (n = 15%)

‘Time-management’ was the only theme identified within cognitive and interpersonal skills. Students who struggled to manage their time effectively found it difficult to incorporate regular PA into their daily routine.

-

12. Social/professional role and identity (Reflective Motivation) (n = 8%)

The most frequent theme within social/professional role and identity was ‘perceiving PA as a part of one’s self-identity’. Students who engaged regularly in PA often considered it integral to their identity. Conversely, students who perceived they did not align with the aesthetic and superficial stereotypes commonly associated with the fitness industry felt less motivated to be active. A specific facilitator emerged among physiotherapy students, who were motivated to be active due to the emphasis on PA within their profession.

-

13. Behavioural regulation (Psychological Capability) (n = 3%)

Within the domain of behavioural regulation, two facilitators were equally prevalent: ‘self-monitoring of PA’ and ‘feedback on progress towards a PA-related goal’. By keeping track of their step count and receiving feedback on walking goals, students were motivated to exceed the average number of daily steps or achieve their personal PA targets.

-

14. Memory, attention, and decision process (Psychological Capability); Optimism (Reflective Motivation) (n = 0%)

No barriers or facilitators relating to the TDF domains of memory, attention and decision process, or optimism were identified.

Discussion

This systematic review used the TDF and COM-B model to identify barriers and facilitators to PA among university students and rank the relative importance of each TDF domain. It is the first review to apply these frameworks in the context of increasing university students’ participation in PA. Twelve TDF domains across all six sub-components of the COM-B model were identified. The three most important TDF domains were ‘environmental context and resources’, ‘social influences’, and ‘goals’. The most common barriers and facilitators were ‘lack of time’, ‘easily accessible exercise options, facilities and equipment’, ‘exercising with others’, and ‘prioritisation of PA compared to other activities’.

The most common barrier to PA was perceived lack of time. This is consistent with previous findings among university students [13, 74] and across other populations [24], For students, lack of time was frequently attributed to a combination of competing priorities and underdeveloped time management skills. Students predominantly prioritised study over PA, as performing well at university is a valued goal and there is a common perception that spending time exercising (at the expense of study) will impede their academic success [53, 58]. Evidence from cognitive neuroscience research, however, suggests that this is a mistaken belief. In addition to its broad physical and mental health benefits, a growing body of evidence demonstrates regular PA can change the structure and function of the brain.

These changes can, in turn, enhance numerous aspects of cognition, including memory, attention, and processing speed [4, 75,76,77], and buffer the negative impact of stress on cognition [78], all of which are important for academic success. However, students are typically unaware of the brain and cognitive health benefits of PA and its potential to improve academic performance, particularly compared to the physical health benefits [37, 40, 64]. Interventions that position participating in PA as a conduit for helping, rather than hindering, academic goals could increase the relative importance of PA to students and therefore increase their motivation to regularly engage in it. The impact that interventions of this nature have on students’ PA is yet to be empirically assessed.

Ineffective time management also contributed to students’ perceived lack of time for PA. Students reported tendencies to procrastinate in the face of overwhelming academic workloads, which left limited time for PA [53]. Additionally, students lacked an understanding of how to organise time for PA around academic timetables, social and family responsibilities, co-curricular activities, and employment commitments [9, 44, 53, 59]. To address these challenges, efforts to develop students’ time management skills will be useful for enabling students to regularly participate in PA. Goal-setting and action planning are two specific examples of such skills that can be integrated into interventions to help students initiate and maintain a PA routine [79]. For example, goal-setting could involve setting a daily PA goal, and action planning could involve planning to engage in a particular PA at a particular time on certain days.

While the most common determinants of university students’ PA levels were not influenced by specific demographic characteristics, several barriers disproportionately impacted women and students with a disability. These findings are in keeping with evidence that PA is lower among these equity-deserving groups compared with the general population [68, 80]. For women, particularly those from Middle Eastern cultures, restrictions were often tied to religious practices and sociocultural norms that limited their opportunities to engage in PA [45, 48, 66]. Additionally, a substantial number of women felt intimidated or self-conscious when exercising in front of others, especially men [48, 49]. They also felt that exercise facilities were more often tailored towards the needs of men, leading to a perception that they were unwelcome in exercise communities [45, 48]. Consequently, women expressed a desire for women-only spaces to exercise to help them overcome these gender-specific barriers to PA [47, 48, 66]. Furthermore, students with a disability faced physical accessibility barriers and perceived stigmatisation that deterred them from PA [50, 52]. The lack of accessible exercise facilities and suitable equipment, programs, and education regarding how to adapt physical activities to accommodate their needs limited their opportunity and ability to participate [52]. Moreover, students with a disability felt stigmatised by others for not fitting into public perceptions of ‘normality’ or the aesthetic values and beauty standards often portrayed by the fitness industry [50]. These barriers for both equity-deserving groups of students are deeply rooted in historical stereotypes that have traditionally excluded women and people with a disability from engaging in various types of PA [81, 82]. Despite growing awareness of these issues, PA inequalities persist due to narrow sociocultural norms, and a lack of diverse representation and inclusion in the fitness industry and associated marketing campaigns [83, 84]. A concerted effort to address PA inequalities across the university sector and fitness industry more broadly is needed. One approach for achieving this is to develop interventions that are tailored to the unique needs of equity-deserving groups, emphasise inclusivity, diversity, and empowerment, and feature women and people with a disability being active.

The “This Girl Can” [85] and “Everyone Can” [86] multimedia campaigns are two examples of health behaviour interventions that were co-developed with key stakeholders (i.e., women and people with a disability, respectively) to tackle PA inequalities. The “This Girl Can” campaign has reached over 3 million women and girls, projecting inclusive and positive messages that aim to empower them to be physically active. Following the widespread reach of the “This Girl Can” campaign, the “Everybody Can” campaign was launched to support the inclusion of people with a disability in the PA sector. Although not tailored for university students, these campaigns provide a useful example for developing interventions that are specifically designed to address key barriers preventing women and people with a disability from participating in PA.

Across the tertiary education sector globally, efforts to elevate opportunities and motivation to include PA as a core part of the student experience will be beneficial for promoting students’ PA at scale. Two intervention approaches that can be implemented to facilitate such an endeavour are environmental restructuring and enablement [17]. These intervention approaches should involve the provision of accessible low-cost exercise options, facilities, and programs, integrating PA into the university curriculum, and mobilising student and staff leadership to encourage students’ participation in PA [9]. Although there is evidence that these approaches can be effective in promoting sustained PA throughout students’ university years and beyond [87], implementation measures such as these are complex. Implementation requires aligning student activity levels with broader university goals and is further complicated by having to compete with other funding priorities and resource allocations. Notably, due to the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on university students’ physical and mental health [88, 89], the post-pandemic era has seen many universities prioritise enhancing student health and wellbeing alongside more traditional strategic goals like academic excellence and workforce readiness. Despite the potential for PA to be used as a vehicle for supporting these strategic goals there is an absence of data on the extent to which this is occurring in the university sector. The limited evidence in this area suggests that some universities have made efforts to support students’ mental health by referring students who access on-campus counselling services to PA programs [90]. However, the uptake and efficacy of such initiatives is rarely assessed, and even less is known about whether PA is being used to support other strategic goals, such as academic success. Therefore, while the potential is there for the university sector to use PA to support students’ mental health and academic performance, to be successful this needs to become a strategic university priority. Given that these strategic priorities are set at the senior leadership level, engaging senior university staff in intervention design and promotion efforts is important to enhance the value of PA in the tertiary education sector.

Implications for intervention development

The current findings provide a high-level synthesis of the most common barriers and facilitators to university students’ physical activity. These findings can be leveraged with behavioural intervention development tools and frameworks (e.g., the BCW [17], Obesity-Related Behavioural Intervention Trials model [91], Intervention Mapping [92], and the Medical Research Council guidelines for developing complex interventions [93, 94]) to develop evidence-based interventions and policies to promote PA. Given that the TDF and COM-B model are directly linked to the BCW framework, applying this process may be particularly useful to translate the current findings into an intervention.

Additionally, current findings can be triangulated with data directly collected from key stakeholders to assist in the development of context-specific interventions. Best practice principles for developing behavioural interventions recommend this approach to ensure a deep understanding of the barriers and facilitators that need to be targeted to increase the likelihood of behaviour change [17]. Consulting stakeholders directly (i.e., university students and staff) to understand their perspectives on the barriers and facilitators to students’ PA also enables an intervention to be appropriately tailored to the target population’s needs and implementation setting. Studies continue to demonstrate the effectiveness of this approach, especially when framed within the context of frameworks directly linked to intervention development frameworks, such as the TDF [95].

Strengths and limitations

The findings of this review should be considered with respect to its methodological strengths and limitations. The credibility and reliability of the research findings are supported by a systematic approach to screening and analysing the empirical data, along with the use of gold-standard behavioural science frameworks to classify barriers and facilitators to PA. The inclusion of qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies of both barriers and facilitators to students’ PA allowed for a comprehensive understanding of the factors that influence students’ PA that have not previously been captured.

While the present review elucidates students’ own perspectives of the factors that influence their activity levels, other stakeholders such as university staff, will also influence the adoption, operationalisation, and scale of PA interventions in a university setting. It will be important for future research to explore factors that influence university decision-makers in these roles to inform large-scale strategies for promoting students' PA.

Additionally, only one study included in the review used the TDF to explore barriers and facilitators to PA [47]. Therefore, it is possible that certain TDF domains may not have been identified because students were not asked relevant questions to assess the influence of those domains on their PA. For instance, domains such as ‘memory, attention, and decision process’, and ‘optimism’ are likely to play a role in understanding the barriers and facilitators to PA despite not being identified in this review.

Moreover, quantitative data were only extracted if ≥ 50% of students endorsed the factor as a barrier or facilitator to PA. This threshold was purposefully applied to maintain a focus on the TDF domains most universally relevant to the broad student population in the context of understanding their barriers and facilitators to PA. It is possible that less frequently reported barriers and facilitators, which may not be as prominently featured in the results, could be relevant to specific groups of students, such as those identified as equity-deserving.

Lastly, a quality appraisal of the included studies was not undertaken. This decision was informed by the aim of the review, which was to describe and synthesise the literature to subsequently map data to the TDF and COM-B rather than assess the effectiveness of interventions or determine the strength of evidence. However, this decision, combined with dual screening 25% of the studies and excluding unpublished studies and grey literature, may introduce sources of error and bias, which should be considered when interpreting the results presented.

Conclusion

PA is an effective, scalable, and empowering means of enhancing physical, mental, and cognitive health. This approach could help students reach their academic potential and cope with the many stressors that accompany student life, in addition to setting a strong foundation for healthy exercise habits for a lifetime. As such, understanding the barriers and facilitators to an active student lifestyle is beneficial. This systematic review applied the TDF and COM-B model to identify and map students’ barriers and facilitators to PA and, in doing so, provides a pragmatic, theory-informed, and evidence-based foundation for designing future context-specific PA interventions. The findings from this review highlight the importance of developing PA interventions that focus on the TDF domains ‘environmental context and resources’, ‘social influences’, and ‘goals’, for which intervention approaches could involve environmental restructuring, education, and enablement. If successful, such strategies could make a significant contribution to improving the overall health and academic performance of university students.

Availability of data and materials

The review protocol is available on PROSPERO. The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study and materials used are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

The term ‘intervention’ was included to identify student barriers and facilitators to engaging in implemented physical activity interventions.

Physical exercise is defined as “a subset of physical activity that is planned, structured, and repetitive”, and purposefully focused on the improvement or maintenance of physical fitness, whereas physical activity is defined as “any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in energy expenditure” [96].

Abbreviations

- BCW:

-

Behaviour Change Wheel

- COM-B:

-

Capability, Opportunity, Model-Behaviour

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- TDF:

-

Theoretical Domains Framework

References

Naci H, Ioannidis JPA. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: metaepidemiological study. BMJ. 2013;347:f5577.

Stensel D, Hardman A, Gill J. Physical Activity and Health: The Evidence Explained. 2021.

Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Hallgren M, Firth J, Veronese N, Solmi M, et al. EPA guidance on physical activity as a treatment for severe mental illness: a meta-review of the evidence and Position Statement from the European Psychiatric Association (EPA), supported by the International Organization of Physical Therapists in Mental Health (IOPTMH). Eur Psychiatry. 2018;54:124–44.

Hotting K, Roder B. Beneficial effects of physical exercise on neuroplasticity and cognition. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2013;37(9):2243–57.

World Health Organization. Global action plan on physical activity 2018–2030: more active people for a healthier world. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Keating XD, Guan J, Piñero JC, Bridges DM. A Meta-Analysis of College Students’ Physical Activity Behaviors. J Am Coll Health. 2005;54(2):116–26.

Worsley JD, Harrison P, Corcoran R. Bridging the Gap: Exploring the Unique Transition From Home, School or College Into University. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.634285

Romaguera D, Tauler P, Bennasar M, Pericas J, Moreno C, Martinez S, et al. Determinants and patterns of physical activity practice among Spanish university students. J Sports Sci. 2011;29(9):989–97.

Deliens T, Deforche B, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Clarys P. Determinants of physical activity and sedentary behaviour in university students: a qualitative study using focus group discussions. BMC Public Health. 2015;15(1):201.

Buckworth J, Nigg C. Physical activity, exercise, and sedentary behavior in college students. J Am Coll Health. 2004;53:28–34.

Nelson MC, Kocos R, Lytle LA, Perry CL. Understanding the perceived determinants of weight-related behaviors in late adolescence: a qualitative analysis among college youth. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2009;41(4):287–92.

Rouse PC, Biddle SJH. An ecological momentary assessment of the physical activity and sedentary behaviour patterns of university students. Health Educ J. 2010;69(1):116–25.

Ferreira Silva RM, Mendonça CR, Azevedo VD, Raoof Memon A, Noll P, Noll M. Barriers to high school and university students’ physical activity: A systematic review. Huertas-Delgado FJ, editor. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(4):e0265913.

Atkins L, Francis J, Islam R, O’Connor D, Patey A, Ivers N, et al. A guide to using the theoretical domains framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):77.

Michie S, Johnston M, Abraham C, Lawton R, Parker D, Walker A. Making psychological theory useful for implementing evidence based practice: a consensus approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(1):26.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7(1):37.

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011;6(1):42.

Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. 1986. xiii, 617–xiii, 617.

Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Educ Behav. 2004;31(2):143–64.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50(2):179–211.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Handbook Theor Soc Psychol. 2012;1:438–59.

Atkins L, Sallis A, Chadborn T, Shaw K, Schneider A, Hopkins S, et al. Reducing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators and strategic behavioural analysis of interventions. Implement Sci. 2020;15:1–22.

Chung OS, Dowling NL, Brown C, Robinson T, Johnson AM, Ng CH, et al. Using the theoretical domains framework to inform the implementation of therapeutic virtual reality into mental healthcare. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2023;50(2):237–68.

Weatherson KA, McKay R, Gainforth HL, Jung ME. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of a school-based physical activity policy in Canada: application of the theoretical domains framework. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):835.

Taylor N, Lawton R, Slater B, Foy R. The demonstration of a theory-based approach to the design of localized patient safety interventions. Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):123.

Garne-Dalgaard A, Mann S, Bredahl TVG, Stochkendahl MJ. Implementation strategies, and barriers and facilitators for implementation of physical activity at work: a scoping review. Chiropractic Manual Therapies. 2019;27(1):48.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021;18(3):e1003583.

Fritz T, Huang E, Murphy G, Zimmermann T. Persuasive technology in the real world: a study of long-term use of activity sensing devices for fitness. In: CHI '14 proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems: April 26–may 01, 2014; Toronto. Ontario: ACM; 2014. p. 487–96.

Tacconelli E. Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(4):226.

The EndNote Team. EndNote. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate; 2013.

O’Mahony B, Kerins C, Murrin C, Kelly C. Barriers and facilitators to the implementation of nutrition standards for school food: a mixed methods systematic review protocol. HRB Open Res. 2020;3:20.

Stuart G, D’Lima D. Perceived barriers and facilitators to attendance for cervical cancer screening in EU member states: a systematic review and synthesis using the Theoretical Domains Framework. Psychol Health. 2022;37(3):279–330.

Bouma SE, van Beek JFE, Diercks RL, van der Woude LHV, Stevens M, van den Akker-Scheek I. Barriers and facilitators perceived by healthcare professionals for implementing lifestyle interventions in patients with osteoarthritis: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2022;12(2):e056831–e056831.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014. Available from: www.behaviourchangewheel.com.

Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13(1):117.

Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101.

Diehl K, Fuchs AK, Rathmann K, Hilger-Kolb J. Students’ Motivation for Sport Activity and Participation in University Sports: a Mixed-Methods Study. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:1–7.

Bellows-Riecken K, Mark R, Rhodes RE. Qualitative elicitation of affective beliefs related to physical activity. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2013;14(5):786–92.

Ramírez-Vélez R. Prevalencia De Barreras Para La Práctica De Actividad Física En. Nutr Hosp. 2015;2:858–65.

Lerner J, Burns C, De Róiste Á. Correlates of physical activity among college students. Recreational Sports Journal. 2011;35(2):95–106.

Snyder K, Lee JM, Bjornsen A, Dinkel D. What gets them moving? College students’ motivation for exercise: an exploratory study. Recreational Sports Journal. 2017;41(2):111–24.

Walsh A, Taylor C, Brennick D. Factors that influence campus dwelling university students’ facility to practice healthy living guidelines. Can J Nurs Res. 2018;50(2):57–63.

Forrest CK, Bruner MW. Evaluating social media as a platform for delivering a team-building exercise intervention: a pilot study. Int J Sport Exercise Psychol. 2017;15(2):190–206.

Ranasinghe C, Sigera C, Ranasinghe P, Jayawardena R, Ranasinghe ACR, Hills AP, et al. Physical inactivity among physiotherapy undergraduates: exploring the knowledge-practice gap. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. 2016;8(1):39.

Othman MS, Mat Ludin AF, Chen LL, Hossain H, Abdul Halim II, Sameeha MJ, et al. Motivations, barriers and exercise preferences among female undergraduates: a need assessment analysis. Muazu Musa R, editor. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2):e0264158.

Leinberger-Jabari A, Al-Ajlouni Y, Ieriti M, Cannie S, Mladenovic M, Ali R. Assessing motivators and barriers to active healthy living among a multicultural college student body: a qualitative inquiry. J Am Coll Health. 2023;71(2):338–42.

Burton NW, Barber BL, Khan A. A qualitative study of barriers and enablers of physical activity among female Emirati university students. IJERPH. 2021;18(7):3380.

silver mp, easty lk, sewell km, georges r, behman a. perspectives on exercise participation among canadian university students. health educ j. 2019;78(7):851–65.

lacaille lj, dauner kn, krambeer rj, pedersen j. psychosocial and environmental determinants of eating behaviors, physical activity, and weight change among college students: a qualitative analysis. J Am Coll Health. 2011;59(6):531–8.

Monforte J, Úbeda-Colomer J, Pans M, Pérez-Samaniego V, Devís-Devís J. Environmental barriers and facilitators to physical activity among university students with physical disability—a qualitative study in Spain. IJERPH. 2021;18(2):464.

Brunette MK, Lariviere M, Schinke RJ, Xing X, Pickard P. Fit to belong: activity and acculturation of Chinese students. J Sport Behav. 2011;34(3):207.

Devine MA. Leisure-time physical activity: experiences of college students with disabilities. Adapt Phys Activ Q. 2016;33(2):176–94.

Kwan MYW, Faulkner GEJ. Perceptions and barriers to physical activity during the transition to university. 2011.

Pan J, Nigg C. Motivation for physical activity among hawaiian, japanese, and filipino university students in Hawaii. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2011;23(1):1–15.

Wilson OWA, Walters SR, Naylor ME, Clarke JC. University students’ negotiation of physical activity and sport participation constraints. Recreational Sports Journal. 2019;43(2):84–92.

Tong HL, Coiera E, Laranjo L. Using a mobile social networking app to promote physical activity: a qualitative study of users’ perspectives. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(12):e11439.

Marmo J. Applying SOCIAL COGNITIVE THEORY TO DEVELOP TARGETED MESSAGES: COLLEGE STUDENTS AND PHYSICAL ACTIVITY. West J Commun. 2013;77(4):444–65.

Hilger-Kolb J, Loerbroks A, Diehl K. ‘When I have time pressure, sport is the first thing that is cancelled’: a mixed-methods study on barriers to physical activity among university students in Germany. J Sports Sci. 2020;38(21):2479–88.

Nannyonjo J, Nsibambi C, Goon D, Amusa L. Physical activity patterns of female students of Kyambogo University, Uganda. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance. 2013;19(4:1):865–73.

El Gilany AH, Badawi K, El Khawaga G, Awadalla N. Physical activity profile of students in Mansoura University. Egypt East Mediterr Health J. 2011;17(08):694–702.

Goldstein SP, Forman EM, Butryn ML, Herbert JD. Differential programming needs of college students preferring web-based versus in-person physical activity programs. Health Commun. 2018;33(12):1509–15.

Griffiths K, Moore R, Brunton J. Sport and physical activity habits, behaviours and barriers to participation in university students: an exploration by socio-economic group. Sport Educ Soc. 2022;27(3):332–46.

King KA, Vidourek RA, English L, Merianos AL. Vigorous physical activity among college students: using the health belief model to assess involvement and social support. AEHD. 2014;4(2):267–79.

Miyawaki C, Ohara K, Mase T, Kouda K, Fujitani T, Momoi K, et al. The purpose and the motivation for future practice of physical activity and related factors in Japanese university students. jhse. 2019;14(1). Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/77873.

Pellerine LP, Bray NW, Fowles JR, Furlano JA, Morava A, Nagpal TS, et al. The influence of motivators and barriers to exercise on attaining physical activity and sedentary time guidelines among Canadian undergraduate students. IJERPH. 2022;19(19):12225.

Aljayyousi GF, Abu Munshar M, Al-Salim F, Osman ER. Addressing context to understand physical activity among Muslim university students: the role of gender, family, and culture. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1452.

Nolan VT, Sandada M, Surujlal J. Perceived benefits and barriers to physical exercise participation of first year university students. 2011.

Chaabna K, Mamtani R, Abraham A, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB, Cheema S. Physical activity and Its barriers and facilitators among university students in Qatar: a cross-sectional study. IJERPH. 2022;19(12):7369.

Awadalla NJ, Aboelyazed AE, Hassanein MA, Khalil SN, Aftab R, Gaballa II, et al. Assessment of physical inactivity and perceived barriers to physical activity among health college students, south-western Saudi Arabia. East Mediterr Health J. 2014;20(10):596–604.

Cooke PA, Tully MA, Cupples ME, Gilliland AE, Gormley GJ. A randomised control trial of experiential learning to promote physical activity. Educ Prim Care. 2013;24(6):427–35.

Musaiger AO, Al-Kandari FI, Al-Mannai M, Al-Faraj AM, Bouriki FA, Shehab FS, et al. Perceived barriers to weight maintenance among university students in Kuwait: the role of gender and obesity. Environ Health Prev Med. 2014;19(3):207–14.

Quintiliani LM, Bishop HL, Greaney ML, Whiteley JA. Factors across home, work, and school domains influence nutrition and physical activity behaviors of nontraditional college students. Nutr Res. 2012;32(10):757–63.

Von Sommoggy J, Rueter J, Curbach J, Helten J, Tittlbach S, Loss J. How does the campus environment influence everyday physical activity? A photovoice study among students of two German universities. Front Public Health. 2020;8:561175.

Pan M, Ying B, Lai Y, Kuan G. Status and Influencing Factors of Physical Exercise among College Students in China: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(20):13465.

Den Ouden L, Kandola A, Suo C, Hendrikse J, Costa RJS, Watt MJ, et al. The influence of aerobic exercise on hippocampal integrity and function: preliminary findings of a multi-modal imaging analysis. Brain Plast. 2018;4(2):211–6.

Maleki S, Hendrikse J, Chye Y, Caeyenberghs K, Coxon JP, Oldham S, et al. Associations of cardiorespiratory fitness and exercise with brain white matter in healthy adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Imaging Behav. 2022;16(5):2402–25.

Müller P, Duderstadt Y, Lessmann V, Müller NG. Lactate and BDNF: key mediators of exercise induced neuroplasticity? J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):1136.

Nicastro TM, Greenwood BN. Central monoaminergic systems are a site of convergence of signals conveying the experience of exercise to brain circuits involved in cognition and emotional behavior. Curr Zool. 2016;62(3):293–306.

Fleig L, Pomp S, Parschau L, Barz M, Lange D, Schwarzer R, et al. From intentions via planning and behavior to physical exercise habits. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2013;14(5):632–9.

Carroll DD, Courtney-Long EA, Stevens AC, Sloan ML, Lullo C, Visser SN, et al. Vital signs: disability and physical activity—United States, 2009–2012. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(18):407.

Ferez S. From women’s exclusion to gender institution: a brief history of the sexual categorisation process within sport. Int J History Sport. 2012;29(2):272–85.

Ferez S, Ruffié S, Joncheray H, Marcellini A, Pappous S, Richard R. Inclusion through sport: a critical view on paralympic legacy from a historical perspective. Social Inclusion. 2020;8(3):224–35.

Rasmussen K, Dufur MJ, Cope MR, Pierce H. Gender marginalization in sports participation through advertising: the case of Nike. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(15):7759.

Richardson EV, Smith B, Papathomas A. Disability and the gym: Experiences, barriers and facilitators of gym use for individuals with physical disabilities. Disabil Rehabil. 2017;39(19):1950–7.

Sport England. This Girl Can | This Girl Can | This girl can. 2015 [cited 2023 Aug 21]. Available from: https://www.thisgirlcan.co.uk/.

ukactive. Everyone Can. 2017 [cited 2023 Aug 21]. Available from: https://everyonecan.ukactive.com/.

Kim M, Cardinal BJ. A Review of How Physical Activity Education Policies in Higher Education Affect College Students’ Physical Activity Behavior and Motivation. In 2016. Available from: https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:210543192.

Ro A, Rodriguez VE, Enriquez LE. Physical and mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic among college students who are undocumented or have undocumented parents. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):1580.

Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e22817.

Brunton JA, Mackintosh CI. Interpreting university sport policy in England: seeking a purpose in turbulent times? Int J Sport Policy Politics. 2017;9(3):377–95.

Czajkowski SM, Powell LH, Adler N, Naar-King S, Reynolds KD, Hunter CM, et al. From ideas to efficacy: the ORBIT model for developing behavioral treatments for chronic diseases. Health Psychol. 2015;34(10):971.

Eldredge LKB, Markham CM, Ruiter RA, Fernández ME, Kok G, Parcel GS. Planning health promotion programmes: an intervention mapping approach. 4th ed. San Francisco (USA): Wiley; 2016.

Craig P, Dieppe P, Macintyre S, Michie S, Nazareth I, Petticrew M. Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2008;337(7676):979–83.

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374:n2061.

Ndupu LB, Staples V, Lipka S, Faghy M, Bessadet N, Bussell C. Application of theoretical domains framework to explore the enablers and barriers to physical activity among university staff and students: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2023;23(1):670–670.

Caspersen CJ, Powell KE, Christenson GM. Physical activity, exercise, and physical fitness: definitions and distinctions for health-related research. Public Health Rep. 1985;100(2):126–31.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their gratitude to the funder, the nib foundation, for its financial support, which was instrumental in facilitating this research. We are also indebted to the Wilson Foundation and the David Winston Turner Endowment Fund for their generous philanthropic contributions, which have supported the BrainPark research team and facility where this research was conducted. Special thanks are owed to the library staff at Monash University for their expertise in conducting systematic reviews, which helped inform the selection of databases and the development of the search strategy.

Funding

This research was supported by nib foundation. The nib foundation had no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the nib foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CB, KR, BP, LA and RS developed the review protocol. CB and BP conducted the search and screened articles, and KR resolved conflicts. CB, KR, BP, LA and RS extracted the barriers and facilitators, mapped barriers and facilitators to the TDF and COM-B model, and interpreted the results. CB drafted the paper. All authors read, revised, and approved the submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The current review contained no participants and did not require ethical approval.

Consent for publication

No individual person’s data in any form is contained in the current article.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Theoretical Domains Framework domains, definitions, and constructs.

Additional file 2.

Search syntax for Ovid MEDLINE.

Additional file 3.

Summary of study characteristics.

Additional file 4.

PRISMA Checklist.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Brown, C.E.B., Richardson, K., Halil-Pizzirani, B. et al. Key influences on university students’ physical activity: a systematic review using the Theoretical Domains Framework and the COM-B model of human behaviour. BMC Public Health 24, 418 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17621-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-17621-4