Abstract

Background

Although the ongoing epidemics of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) may have affected the mortality trend of the nation, the national level assessment of excess mortality (changes in overall mortality in the entire population) is still scarce in Korea. Therefore, this study evaluated the excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea using the certified mortality data.

Methods

Monthly mortality and population data from January 2013 to June 2022 was obtained from the National Health Insurance Service database and Statistics Korea. A quasi-Poisson interrupted time-series model adjusted for age structure, population, seasonality, and long-term trends was used to estimate the counterfactual projections (expected) of mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 to June 2022). The absolute difference (observed—expected) and ratio (observed / expected) of mortality were calculated. Stratified analysis based on pandemic years (years 2020, 2021, and 2022), sex, and age groups (aged 0–4, 5–19, 20–64, and ≥ 65 years) were conducted.

Results

An 8.7% increase in mortality was observed during the COVID-19 pandemic [absolute difference: 61,277 persons; ratio (95% confidence interval (CI)): 1.087 (1.066, 1.107)]. The gap between observed and estimated mortality became wider with continuation of the pandemic [ratio (95% CI), year 2020: 1.021 (1.003, 1.040); year 2021: 1.060 (1.039, 1.080), year 2022: 1.244 (1.219, 1.270)]. Although excess mortality across sex was similar, the adult [aged 20–64, ratio (95% CI): 1.059 (1.043, 1.076)] and elderly [aged 65-, ratio (95% CI): 1.098 (1.062, 1.135)] population showed increased excess mortality during the pandemic.

Conclusions

Despite Korea's successful quarantine policy response, the continued epidemic has led to an excess mortality. The estimated mortality exceeded the number of deaths from COVID-19 infection. Excess mortality should be monitored to estimate the overall impact of the pandemic on a nation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Backgrounds

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has become a global health issue since the first case was reported in Wuhan, China in December 2019 [1, 2]. As of August 14, 2022, 6.4 million deaths have occurred worldwide due to COVID-19, and 25,623 people have died in Korea [3].

In addition to mortality directly related to COVID-19 infection, changes in overall mortality in the entire population (excess mortality) including COVID-19 death have been reported [4]. Increase in overall mortality were reported in countries with rapid surge of COVID-19 cases, whereas decrease in overall mortality was observed in countries that minimized the epidemic [4,5,6,7,8,9]. These changes in excess mortality could be attributed to factors such as absolute and/or relative shortage in medical services for non-COVID-19 disease, changes in the incidence of infectious diseases due to increased public hygiene, and changes in healthcare seeking behavior of the public during the pandemic [10,11,12].

With rigorous contact tracing, testing of all contacts, and implementation of early quarantine strategies, Korea was regarded as one of the countries which successfully managed the COVID-19 pandemic [13, 14]. A previous interrupted time-series study in Korea showed stable mortality patterns during the early pandemic period [10]. No or minimum increase in the mortality of general population were reported in the year 2020 [4, 15].

However, since the third quarter of the year 2021, Korea is showing a rapid surge of COVID-19 patients. Delayed vaccination, emergence of delta variants, and governmental movement for the gradual restoration of normal life may be the causes for the continued increase of COVID-19 cases [16]. Inadequate or overwhelmed capacity to perform testing, contact tracing, isolation, and quarantine during major epidemics may be another reason [17].

With the rapid increase of COVID-19 patients, excess mortality may have been observed in Korea as in other countries. Disrupted emergency medical system and standard pathway for the non-COVID-19 disease management during epidemics [18,19,20,21] may have affected the nation’s overall mortality. An increase in response time and poorer prognosis were reported in patients seeking emergency care during the pandemic period in Korea [19,20,21]. In addition, delays in health screening and non-urgent medical visits were observed during the pandemic [18, 22,23,24,25,26].

On the other hand, non-pharmaceutical measures to manage COVID-19 such as social distancing, regular hand washing, and the use of facemasks may have reduced the spread of infectious disease, and eventually resulted in a decrease in the mortality rate in Korea [8, 27,28,29]. Decrease in air pollution levels during the pandemic period may contribute to decline in the mortality rate [30].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, above mentioned societal factors affecting the overall mortality of the nation have constantly emerged and changed. However, the national-level assessment of excess mortality during the pandemic is still scarce in Korea. With this perspective, this study aimed to investigate the excess mortality in Korea by investigating if the overall mortality rate of the general population in Korea deviated from the historical trend during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design

In addition to daily COVID-19 incidences and death counts, excess mortality compares the observed number of overall mortalities during the pandemic and expected mortalities based on trends during the pre-pandemic period [11]. It is a useful metric to estimate the direct and indirect impact of COVID-19 on the society and enables better comparison between countries with different COVID-19 diagnostic capacities and death registration systems.

The first epidemic of COVID-19 infection in Korea was reported between late February and early March 2020 [13]. The World Health Organization declared COVID-19 as pandemic on March 11, 2020 [31]. Therefore, the starting point of the pandemic in Korea was set as March 2020 as in previous study [10], and the observed and expected mortalities since March 2020 were compared in this study.

Data inputs

All-cause mortality (date of deaths; sex and age of the dead) data between January 2013 and June 2022 were obtained from National Health Insurance Service (NHIS) database. Information regarding causes of deaths were not opened to researchers due to the validity issue. Overall, information of 2,810,905 (men: 1,523,727, women: 1,287,178) deaths between January 2013 and June 2022 were analyzed in this study.

To adjust for population size of each age group (5-year intervals from 0–4 to 80–84, and 85 years or older) during the study period, the monthly registered population (from January 2013 to June 2022) was obtained from the Korean Statistical Office [32]. To adjust for different age structures across the study period, age-standardized rates were calculated [33, 34].

In addition to the all-cause mortality data from the NHID, the Korea Center for Disease Control (KCDC) provided information regarding COVID-19 patients (sex, age, date of diagnosis, and date of death). However, the information was only available from January 2020 to March 2022 due to the time required for the epidemiological investigation. To estimate the degree of COVID-19 epidemics in Korea, we age-standardized COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates and visually inspected the patterns.

Statistical analysis

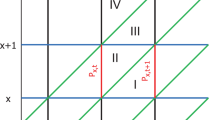

Monthly mortality data from January 2013 to February 2020 and a quasi-Poisson regression model was used to estimate the mortalities during the pandemic period (from March 2020 to June 2022):

The numbers of monthly mortality (\(\mu_{t,\ x}\): number of mortality on t year-month in x age group) were assumed to follow a quasi-Poisson distribution allowing overdispersion. \({T}_{t}\) is the time (in month unit) since January 2013; A is the categorical variable representing age groups. M is the month indicator variable and 4 degrees of freedom was used to adjust seasonality [10]. \(P_{t,\;x}\) is the monthly population in age group x in t year-month.

The counterfactual (without COVID-19 pandemic) monthly mortality for March 2020 to June 2022 were estimated. Absolute difference (observed—expected) and ratio (observed / expected) of mortality were calculated by comparing estimated and observed mortalities. The 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) for ratio was calculated based on the upper and lower projection values of expected mortalities. Stratified analysis based on pandemic years (2020, 2021, and 2022), sex, and age groups (aged 0–4, 5–19, 20–64, ≥ 65 years) were conducted.

To estimated the overall changes in the mortality patterns during the pandemic, a quasi-Poisson interrupted time-series analysis was conducted by introducing \({\upbeta }_{4}{(T}_{t}-{T}_{0})\cdot { I}_{t}\) term to the regression model. \({T}_{0}\) is the time when pandemic began in Korea (March 2020) and \({I}_{t}\) is the categorial variable representing the time before (\({I}_{t}=0,\) from January 2013 to February 2020) and after the pandemic (\({I}_{t}=1,\) from March 2020 to June 2022). Based on a previous study showing minimum changes in the mortality rate of the Korean population during the early pandemic [10], a slope change model was selected for the interrupted time series analysis [35]. \({\upbeta }_{4}\) refers to the changes of slope (relative risk) in mortality trend after the pandemic and robust standard errors were calculated [36, 37].

To determine the effects of COVID-19 deaths on excess mortality, we subtract the number of COVID-19 deaths from all-cause deaths and evaluate the monthly age-standardized mortality patterns of non-COVID-19. In addition, monthly COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 mortality rates for each 5-year age groups were evaluated from January 2020 to March 2022. SAS (version 9.4, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and R statistical software (version 4.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) were used. The level of statistical significance was set at a p-value < 0.05.

Results

Figure S1 shows the monthly age-standardized incidence and mortality rates of COVID-19 patients from January 2020 to March 2022 (see Additional file 1). After two waves of the epidemics in the year 2020 (March and December 2020), there has been a continuous increase in the number of COVID-19 patients and mortality since June 2021. The marked increase in COVID-19 incidence and mortality was observed in early 2022.

A total of 768,341 all-cause deaths occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020 to June 2022) in Korea (Table 1). Deviation from the historical age-standardized mortality trend was observed from the end of 2021 (Fig. 1). The slope change estimate [relative risk (95% confidence interval (CI))] for mortality trend after the pandemic (March 2020) was 1.007 (1.004, 1.010).

Overall 8.7% increase in mortality was estimated during the pandemic [absolute difference between observed – expected number of deaths: 61,277 persons; ratio (95% CI): 1.087 (1.066, 1.107)] (Table 1). The difference between observed and expected mortality became wider with the continuation of the pandemic [ratio (95% CI), year 2020: 1.021 (1.003, 1.040); year 2021: 1.060 (1.039, 1.080), year 2022: 1.244 (1.219, 1.270)].

Observed deaths exceeded the expected deaths during the pandemic among both men [absolute difference: 31,016 persons; ratio (95% CI): 1.081 (1.062, 1.100)] and women [absolute difference: 30,466 persons; ratio (95% CI): 1.094 (1.070, 1.118)]. Men and women both showed increased ratio of death in the year 2022 [ratio (95% CI): men: 1.210 (1.188, 1.233), women: 1.285 (1.256, 1.315)] compared to early pandemic years (years 2020 and 2021).

Table 2 shows the stratified analysis based on age groups. Although there were no differences between the number of observed and expected deaths during the pandemic in young age groups [ratio (95% CI), aged 0 to 4: 0.992 (0.929, 1.059), aged 5 to 19: 1.070 (0.989, 1.157)], observed mortality exceeded the expected mortality in older age groups [ratio (95% CI), aged 20–64 years: 1.059 (1.043, 1.076), aged ≥ 65 years: 1.098 (1.062, 1.135)]. In the year 2022, the estimated difference [ratio (95% CI)] between observed and expected deaths became wider in 0 to 4 [1.096 (1.018, 1.179)], 20 to 64 [1.116 (1.097, 1.135)], and ≥ 65 [1.291 (1.245, 1.339)] years age groups as compared to early pandemic years. However, greatest difference was observed in the year 2021 in 5 to 19 years age group [ratio (95% CI): 1.111 (1.025, 1.203)].

Figure S2 shows the mortality patterns of all-cause (COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 deaths) and non-COVID-19 mortalities (see Additional file 1). The contribution of excess mortality of COVID-19 deaths increased since December 2021. Figure S3 shows the COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 mortality patterns by each 5-year age groups. There was a marked increase in COVID-19 mortality rates in year 2022 and a larger increase in the older age group (aged over 65).

Discussion

This study estimated the excess mortality during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. Overall, an 8.7% increase in mortality was observed during the pandemic (March 2020 to June 2022). Although the monthly age-standardized mortality of the nation followed the historical trend during the early pandemic, a marked increase was observed since the third quarter of 2021. The increase was greater in the adult and elderly population as compared to adolescents and children.

Underlying mechanism of the excess mortality observed during the pandemic in this study can be speculated as follows. First, the delays and absence of timely and proper medical services since the start of the pandemic could have resulted in late increase in mortality [38]. In a Korean survey with nationally representative sample, 26% and 8% of respondents reported delays in health screening and non-urgent medical visits during the pandemic, respectively [22]. By analyzing the nationwide health insurance claim data which covers all the health facilities of the nation, significant changes in outpatient visits (-9.38%), inpatient admission (-3.82%), hospital visits for diabetes (-2.90%), hypertension (-3.48%), and mental health (-2.60%) were observed in the year 2020 as compared to the previous year [18]. Risk of nosocomial infections and strict implication of social distancing measures may be the reasons for avoiding medical services [10, 18]. Increased mortality can occur months to years after the misses and delays of proper medical services [22, 39].

Second, disruption in emergency medical system may result in immediate increase in mortality rates. Medical resources including emergency departments, ambulances, governmental healthcare officials, and paramedics were mobilized for COVID-19 management in Korea [13, 40]. Therefore, the medical system covering non-COVID-19 emergency patients may have weakened [10]. Since the early stage of the pandemic, the time from the onset of symptom to hospital arrival became longer, and the poor prognosis of the emergency patients were reported [19,20,21, 41]. Although the in-hospital mortality rate did not change, the out-of-hospital deaths (deaths at home, public facilities, on the way to hospital) increased in Korea in year 2020 [10]. Disruption of emergency medical system may have worsened during the unprecedented increase of COVID-19 patients during the delta and omicron variants epidemics, which began in the third quarter of 2021 (Figure S1).

Third, the capability of critical care management for non-COVID-19 patients may be disrupted. Shortages of intensive care beds, logistics, and trained personnel to manage severe patients were reported in countries with a rapid surge of COVID-19 cases [42,43,44]. The shortage of hospital beds was also reported in Korea during the first epidemic in early 2020 [45].

Although the Korean government mobilized infectious wards and intensive care beds to prepare for further epidemics, an unprecedented increase of COVID-19 patients since June 2021 (Figure S1) may induce a shortage in the capability for critical care management, which may eventually increase the mortality of emergent COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 disease patients [46, 47].

Fourth, the re-emergence of infectious respiratory disease other than COVID-19 might have attributed to increased mortality during the winter period of 2021–2022. Non-pharmaceutical measures (e.g. hand-washing, facemask use, social distancing) to control COVID-19 were effective in controlling other respiratory diseases worldwide [48, 49]. In 2020, Korea reported a decrease incidence of influenza and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infections, as well as overall respiratory mortality [10, 50]. However, the effect of non-pharmaceutical measures to prevent respiratory infectious diseases might have changed due to efforts by the government to gradually restore normal life and decreased participation in social distancing by the public.

For example, unlike the marked decrease in mobility during the early COVID-19 epidemic, there were minimal changes in mobility during the delta and omicron variant epidemics in year 2021 and 2022 in Korea [51]. RSV outbreak reappeared in Korea between November 2021 and January 2022, however, influenza infection remained minimum [51]. The re-emergence of respiratory infectious disease including RSV may have resulted in increased mortality in the winters of years 2021–2022, as observed in this study. However, this must be confirmed with further cause-specific mortality data analysis.

The adult and elderly population showed increased excess mortality during the year 2022. The excess mortality due to COVID-19 deaths increased from December 2021 (Figure S2). Age has been reported to be a significant risk factor for COVID-19 mortality and complications [52]. Therefore, increased infection during the delta and omicron variant epidemics (since June 2021) may have resulted in increased mortality rate in adult and elderly population with COVID-19 infection. The age-group specific COVID-19 mortality pattern in our study also showed a marked increase in the elderly population in year 2022 (Figure S3). In addition, an increased mortality in older age groups from the end of 2021 to 2022 might represent lagged health consequences which appears months or years after the delay or misses of proper medical services [22, 39].

Increase in mortality of ages 5 to 19 during the year 2021 coincides with rapid increase in COVID-19 patients of that particular age group [53]. Although COVID-19 vaccination for adults started in February 2021, the vaccination for adolescents (12 to 17 years) was delayed until October 2021 in Korea [54]. Until the adoption of vaccination, 12 to 17 years age group showed highest incidence since the second quarter of 2021 [53], and this may have resulted in higher excess mortality of that age group during year 2021. Age-specific mortality patterns of the younger age group in our study also showed an increase in COVID-19 mortality since July 2021 (Figure S3).

On the other hand, several studies have reported an increase in suicidal mortalities and a deterioration in mental health in the younger age group in Korea during the pandemic [55, 56]. Although the total number of suicides did not change from the pre-pandemic trends early in the pandemic [10], increasing patterns were seen in women and younger age group (aged ≤ 34 years) [55]. A nationwide cross-sectional survey on Korean adolescents showed increasing patterns of sadness and suicidalities in year 2021 compared to the 15 years of pre-pandemic trends [56]. Unprecedented changes during the pandemic such as school closures, social distancing, and changes in daily activities may have negatively impacted the metal health and its development in children and adolescents [57,58,59].

Excess mortality can be a useful marker for estimating the impact of COVID-19 pandemic on society [11]. Although absolute number of COVID-19 cases and deaths can be affected by factors like testing capacity, validity of death registration, and political pressure; excess mortality addresses both direct and indirect impacts of COVID-19 [60].

However, mortality represents the end stage health consequences of severe COVID-19 infection cases. COVID-19 patients experience a wide range of health outcomes including long COVID [61]. Therefore, not only the excess morbidity, but also metrics such as disability adjusted life years (DALYs) and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) should be addressed in the future studies to estimate the true health impact of COVID-19 [38, 61].

The Korean government eased on various policies and measures to prevent COVID-19 infection, such as lifting social distancing and mandatory quarantine of international arrivals, and allowing face-to-face visits for nursing hospitals and facilities since April 2022 [62,63,64]. This decision was based on high vaccination rate, low fatality rate of COVID-19 patients, and high reservoir of emergency beds [63].

However, Korea has been reporting the highest numbers of new COVID-19 patients in August 2022 [3]. Considering the high excess mortality observed in this study during the time period with marked increase in COVID-19 patients, the mortality rate of recent months would have deviated more severely from the historical trends. Therefore, diseases other than COVID-19 and general medical services for public should be monitored. In addition, eased non-pharmaceutical measures to prevent COVID-19 infection should be reconsidered until the excess mortality became minimum.

This study had some limitations. First, analyses to address which diseases caused the increase in excess mortality were not available due to data constraints. To ensure validity, Statistics Korea is releasing cause-specific mortality data with one year of time lag. Currently, only mortality count data for the years 2021 and 2022 was accessible through the NHIS database. We believed timely analysis for generating scientific evidence was crucial during the pandemic period and conducted this study based on available mortality data.

Second, due to the ecological nature of this study, we were not able to depict particular factors affecting mortality of the Korean. Diverse measures and strategies have been devised and introduced simultaneously in Korea and around the world to combat the pandemic. Since this study is conducted based on single time point distinguishing pandemic from pre-pandemic period (March 2020), the impact of single measures or factors on excess mortality could not be addressed.

Third, the estimation of excess mortality is influenced by several factors, such as the selection of models, definition of baseline and projection periods, and adjustments for potential confounders [4, 65, 66]. In this study, efforts were made to account for long-term mortality trends, and adjustment were made for monthly variations in population age structure and seasonality. The analysis models were selected based on a previous study that evaluated the changes in the overall mortality pattern in Korea during the early stages of the pandemic [10]. However, conducting sensitivity analyses using different analytical choices is crucial to comprehensively assess the mortality burden associated with COVID-19 [65].

Conclusions

The excess mortality was 8.7% (n = 61,277) during the COVID-19 pandemic (between March 2020 and June 2022) in Korea. Excess mortality increased with continuation of the pandemic, showing considerable increase in year 2022. In addition to reporting daily COVID-19 incidence and mortality count, periodic assessment of excess mortality should be conducted to estimate the indirect impact of COVID-19 on the society. Moreover, the government should closely monitor the medical system to manage diseases other than COVID-19 during the pandemic period.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the National Health Insurance Service, Korea. Restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for this study. Data are available from the authors (contact C.H.) with the permission of the National Health Insurance Service, Korea.

References

Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, Liang WH, Ou CQ, He JX, Liu L, Shan H, Lei CL, Hui DSC, et al. Clinical characteristics of Coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–20.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, Zhang L, Fan G, Xu J, Gu X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

World Health Organization. COVID-19 Weekly Epidemiological Update (Edition 105 published 17 August 2022). 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---17-august-2022.

Islam N, Shkolnikov VM, Acosta RJ, Klimkin I, Kawachi I, Irizarry RA, et al. Excess deaths associated with Covid-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ. 2021;373:n1137.

Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Sabo RT, Zimmerman EB. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes in the US, March 1, 2020, to January 2, 2021. JAMA. 2021;325(17):1786–9.

Weinberger DM, Chen J, Cohen T, Crawford FW, Mostashari F, Olson D, Pitzer VE, Reich NG, Russi M, Simonsen L. Estimation of excess deaths associated with the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States, March to May 2020. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1336–44.

Scortichini M, Schneider dos Santos R, De’Donato F, De Sario M, Michelozzi P, Davoli M, Masselot P, Sera F, Gasparrini A. Excess mortality during the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy: a two-stage interrupted time-series analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(6):1909–17.

Gregory G, Zhu L, Hayen A, Bell KJ. Learning from the pandemic: mortality trends and seasonality of deaths in Australia in 2020. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51(3):718–26.

Kung S, Doppen M, Black M, Hills T, Kearns N. Reduced mortality in New Zealand during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Lancet. 2021;397(10268):25.

Han C. Changes in mortality rate of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time series study in Korea. Int J Epidemiol. 2022;51(5):1396–407.

Beaney T, Clarke JM, Jain V, Golestaneh AK, Lyons G, Salman D, Majeed A. Excess mortality: the gold standard in measuring the impact of COVID-19 worldwide? J R Soc Med. 2020;113(9):329–34.

Kondilis E, Tarantilis F, Benos A. Essential public healthcare services utilization and excess non-COVID-19 mortality in Greece. Public Health. 2021;198:85–8.

Oh J, Lee J-K, Schwarz D, Ratcliffe HL, Markuns JF, Hirschhorn LR. National response to COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea and lessons learned for other countries. Health Syst Reform. 2020;6(1):e1753464.

The Government of the Republic of Korea: All about Korea's response to COVID-19. 2020. Available at: https://www.mofa.go.kr/eng/brd/m_22591/view.do?seq=35&srchFr=&srchTo=&srchWord=&srchTp=&multi_itm_seq=0&itm_seq_1=0&itm_seq_2=0&company_cd=&company_nm=&page=1&titleNm=. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

Shin MS, Sim B, Jang WM, Lee JY. Estimation of excess all-cause mortality during COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(39):e280.

Kwon SL, Oh J. COVID-19 vaccination program in South Korea: A long journey toward a new normal. Health Policy Technol. 2022;11(2):100601.

Oh J, Hwang S, Long KQ, Kim M, Park K, Kwon S, Artaza Barrios OE, Torres I, Kavanagh M, Kondo N. Real world evidence of trace, test, isolation, and quarantine impact on the COVID-19 pandemic response performance. 2021.

Arsenault C, Gage A, Kim MK, Kapoor NR, Akweongo P, Amponsah F, Aryal A, Asai D, Awoonor-Williams JK, Ayele W, et al. COVID-19 and resilience of healthcare systems in ten countries. Nat Med. 2022;28(6):1314–24.

Lee SH, Mun YH, Ryoo HW, Jin SC, Kim JH, Ahn JY, Jang TC, Moon S, Lee DE, Park H. Delays in the management of patients with acute ischemic stroke during the COVID-19 outbreak period: a multicenter study in Daegu. Korea Emerg Med Int. 2021;2021:6687765.

Ahn JY, Ryoo HW, Cho JW, Kim JH, Lee SH, Jang TC. Impact of the COVID-19 outbreak on adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes in Daegu, South Korea: an observational study. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2021;8(2):137–44.

Lim D, Park SY, Choi B, Kim SH, Ryu JH, Kim YH, Sung AJ, Bae BK, Kim HB. The comparison of emergency medical service responses to and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in an Area of Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(36):e255.

Kang E, Yun J, Hwang S-H, Lee H, Lee JY. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in the healthcare utilization in Korea: Analysis of a nationwide survey. J Infect Public Health. 2022;15(8):915–21.

Lee M, You M. Avoidance of healthcare utilization in South Korea during the Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(8):4363.

Helal A, Shahin L, Abdelsalam M, Ibrahim M. Global effect of COVID-19 pandemic on the rate of acute coronary syndrome admissions: a comprehensive review of published literature. Open Heart. 2021;8(1):e001645.

Kim S, Ro YS. Ko S-k, Kim T, Pak Y-S, Han S-H, Moon S: The impact of COVID-19 on the patterns of emergency department visits among pediatric patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;54:196–201.

Lee K, Lee YY, Suh M, Jun JK, Park B, Kim Y, Choi KS. Impact of COVID-19 on cancer screening in South Korea. Sci Rep. 2022;12(1):11380.

Liang M, Gao L, Cheng C, Zhou Q, Uy JP, Heiner K, Sun C. Efficacy of face mask in preventing respiratory virus transmission: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020;36:101751.

Jefferson T, Del Mar C, Dooley L, Ferroni E, Al-Ansary LA, Bawazeer GA, van Driel ML, Foxlee R, Rivetti A. Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses: systematic review. BMJ. 2009;339:b3675.

Fong MW, Gao H, Wong JY, Xiao J, Shiu EYC, Ryu S, Cowling BJ. Nonpharmaceutical measures for pandemic influenza in nonhealthcare settings-social distancing measures. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(5):976–84.

Han C, Hong YC. Decrease in ambient fine particulate matter during COVID-19 crisis and corresponding health benefits in Seoul, Korea. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(15):5279.

Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO Declares COVID-19 a Pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–60.

Statistics Korea. Statistical Database Website. 2021. Available at: https://kosis.kr/statHtml/statHtml.do?orgId=101&tblId=DT_1B040A3&vw_cd=MT_ETITLE&list_id=A_7&scrId=&language=en&seqNo=&lang_mode=en&obj_var_id=&itm_id=&conn_path=MT_ETITLE&path=%252Feng%252FstatisticsList. Accessed 14 Aug 2022.

Ahmad OB, Boschi-Pinto C, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Lozano R, Inoue M. Age standardization of rates: a new WHO standard. Geneva: WHO. 2001;9(10):1–14.

Jensen OM, Storm HH. Cancer registration: principles and methods. Reporting of results. IARC Sci Publ. 1991;(95):108–25.

Bernal JL, Cummins S, Gasparrini A. Interrupted time series regression for the evaluation of public health interventions: a tutorial. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(1):348–55.

Humphreys DK, Gasparrini A, Wiebe DJ. Evaluating the Impact of Florida’s “Stand Your Ground” Self-defense Law on Homicide and Suicide by Firearm: An Interrupted Time Series Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):44–50.

Donald WKA. Heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation consistent covariance matrix estimation. Econometrica. 1991;59(3):817–58.

Clarke JM, Majeed A, Beaney T. Measuring the impact of Covid-19. BMJ. 2021;373:n1239.

Maringe C, Spicer J, Morris M, Purushotham A, Nolte E, Sullivan R, Rachet B, Aggarwal A. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer deaths due to delays in diagnosis in England, UK: a national, population-based, modelling study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(8):1023–34.

Pak YS, Ro YS, Kim SH, Han SH, Ko SK, Kim T, Kwak YH, Heo T, Moon S. Effects of emergency care-related health policies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea: a quasi-experimental study. J Korean Med Sci. 2021;36(16):e121.

Choi H, Lee JH, Park HK, Lee E, Kim MS, Kim HJ, Park BE, Kim HN, Kim N, Jang SY. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on patient delay and clinical outcomes for patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37(21):e167.

Xie J, Tong Z, Guan X, Du B, Qiu H, Slutsky AS. Critical care crisis and some recommendations during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(5):837–40.

Moghadas SM, Shoukat A, Fitzpatrick MC, Wells CR, Sah P, Pandey A, Sachs JD, Wang Z, Meyers LA, Singer BH, et al. Projecting hospital utilization during the COVID-19 outbreaks in the United States. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2020;117(16):9122–6.

Tsai TC, Jacobson BH, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Association of community-level social vulnerability with US acute care hospital intensive care unit capacity during COVID-19. Healthcare. 2022;10(1):100611.

Her M. Repurposing and reshaping of hospitals during the COVID-19 outbreak in South Korea. One Health. 2020;10:100137.

Demoule A, Fartoukh M, Louis G, Azoulay E, Nemlaghi S, Jullien E, Desnos C, Clerc S, Yvin E, Mellati N, et al. ICU strain and outcome in COVID-19 patients—A multicenter retrospective observational study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(7):e0271358.

Dang A, Thakker R, Li S, Hommel E, Mehta HB, Goodwin JS. Hospitalizations and mortality from Non–SARS-CoV-2 causes among medicare beneficiaries at US hospitals during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(3):e221754–e221754.

van Summeren J, Meijer A, Aspelund G, Casalegno JS, Erna G, Hoang U, Lina B, de Lusignan S, Teirlinck AC, Thors V. Low levels of respiratory syncytial virus activity in Europe during the 2020/21 season: what can we expect in the coming summer and autumn/winter? Eurosurveillance. 2021;26(29):2100639.

Olsen SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Budd AP, Brammer L, Sullivan S, Pineda RF, Cohen C, Fry AM. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. Am J Transplant. 2020;20(12):3681–5.

Kim J-H, Roh YH, Ahn JG, Kim MY, Huh K, Jung J, Kang J-M. Respiratory syncytial virus and influenza epidemics disappearance in Korea during the 2020–2021 season of COVID-19. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;110:29–35.

Kim J-H, Kim HY, Lee M, Ahn JG, Baek JY, Kim MY, Huh K, Jung J, Kang J-M. Respiratory syncytial virus outbreak without influenza in the second year of the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: A National Sentinel Surveillance in Korea, 2021–2022 Season. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37(34):e258.

Gandhi RT, Lynch JB, Del Rio C. Mild or moderate Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(18):1757–66.

Lee H, Choi EH, Park YJ, Choe YJ. Short term impact of Coronavirus disease 2019 vaccination in children in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2022;37(17):e124.

June Choe Y, Yi S, Hwang I, Kim J, Park YJ, Cho E, Jo M, Lee H, Hwa Choi E. Safety and effectiveness of BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine in adolescents. Vaccine. 2022;40(5):691–4.

Ryu S, Nam HJ, Jhon M, Lee JY, Kim JM, Kim SW. Trends in suicide deaths before and after the COVID-19 outbreak in Korea. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(9):e0273637.

Woo HG, Park S, Yon H, Lee SW, Koyanagi A, Jacob L, Smith L, Cho W, Min C, Lee J, et al. National trends in sadness, suicidality, and COVID-19 pandemic-related risk factors among South Korean adolescents from 2005 to 2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2314838–e2314838.

Kauhanen L, Wan Mohd Yunus WMA, Lempinen L, Peltonen K, Gyllenberg D, Mishina K, et al. A systematic review of the mental health changes of children and young people before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32(6):995–1013.

Park B, Kim J, Yang J, Choi S, Oh K. Changes in mental health of Korean adolescents before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a special report using the Korea Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Epidemiol Health. 2023;45:e2023019.

Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–50.

Wang H, Paulson KR, Pease SA, Watson S, Comfort H, Zheng P, Aravkin AY, Bisignano C, Barber RM, Alam T, et al. Estimating excess mortality due to the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic analysis of COVID-19-related mortality, 2020–21. The Lancet. 2022;399(10334):1513–36.

Briggs A, Vassall A. Count the cost of disability caused by COVID-19. In.: Nature Publishing Group; 2021.

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. COVID-19 measures for infection-vulnerable facilities eased from June 20, Press Release (June 17 2022). 2022. Available at: https://www.mohw.go.kr/eng/nw/nw0101vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=1007&MENU_ID=100701&page=4&CONT_SEQ=371874. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Social distancing restrictions to be lifted starting April 18, Press Release (April 15 2022). 2022. Available at: https://www.mohw.go.kr/eng/nw/nw0101vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=1007&MENU_ID=100701&page=1&CONT_SEQ=371146. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency. Mandatory quarantine for international arrivals is lifted from June 8, Press Release (June 3 2022). 2022. Available at: https://www.mohw.go.kr/eng/nw/nw0101vw.jsp?PAR_MENU_ID=1007&MENU_ID=100701&page=1&CONT_SEQ=371711. Accessed 29 Aug 2022.

Levitt M, Zonta F, Ioannidis J. Excess death estimates from multiverse analysis in 2009–2021. Eur J Epidemiol. 2023:1–11.

Levitt M, Zonta F, Ioannidis JP. Comparison of pandemic excess mortality in 2020–2021 across different empirical calculations. Environ Res. 2022;213:113754.

Acknowledgements

This study is conducted as part of the public-private joint research on the COVID-19 issues jointly hosted by the National Health Insurance Service and the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Agency. This study used the database of the National Health Insurance Service for policy and academic research. The aim and conclusion of this study are irrelevant to the National Health Insurance Service, Republic of Korea and the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Agency. The research number of this study is KDCA-NHIS-2022-1-530.

Statement on guidelines

This study complies with relevant guidelines and regulations. All the data were provided by the National Health Insurance Service (NHIS). This study used the de-identified data provided by the Statistics Korea and the NHIS.

Funding

This research was supported by the research fund of Chungnam National University. The funding source had no role in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit for publication.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

C.H. conceived and designed the study. C.H. and H.J performed the statistical analysis and C.H interpreted the results and wrote the initial manuscript. J.O reviewed the manuscript. All authors provided input to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study used the de-identified secondary data provided by the Statistics Korea and the National Health Insurance Service with no direct involvement of the participants. The data used in this study were anonymized before provision to the authors. Therefore, the patient informed consent procedure is waived by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (E-2207–021-1337). All methods were carried out following relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Monthly age-standardized COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates in Korea (from January 2020 to March 2022). Data was provided from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Agency (KCDC). The time period used for COVID-19 incidence and mortality data is different from the all-cause mortality data used in the main analysis due to the time that was required for the epidemiological investigation to confirm COVID-19 deaths. Figure S2. Age standardized mortality rate of Korea from January 2013 to June 2022. Circled points and the solid line represent all-cause (COVID19 and non-COVID19) mortality rates. Crosshair points represent non-COVID-19 mortality rates (from January 2020 to March 2022). The dotted line represents expected all-cause mortality trends estimated based on the pre-COVID19 (Jan 2013 to Feb 2020) mortality trend. Figure S3. COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 death rates (number of deaths/number of population) by 5-year age groups.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Han, C., Jang, H. & Oh, J. Excess mortality during the Coronavirus disease pandemic in Korea. BMC Public Health 23, 1698 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16546-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16546-2