Abstract

Background

Universal recommendation for antiretroviral drugs and their effectiveness has put forward the challenge of assuring a chronic and continued care approach to PLHIV (People Living with HIV), pressured by aging and multimorbidity. Integrated approaches are emerging which are more responsive to that reality. Studying those approaches, and their relation to the what of delivery arrangements and the how of implementation processes, may support future strategies to attain more effective organizational responses.

Methods

We reviewed empirical studies on either HIV, multimorbidity, or both. The studies were published between 2011 and 2020, describing integrated approaches, their design, implementation, and evaluation strategy. Quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods were included. Electronic databases reviewed cover PubMed, SCOPUS, and Web of Science. A narrative analysis was conducted on each study, and data extraction was accomplished according to the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care taxonomy of health systems interventions.

Results

A total of 30 studies, reporting 22 different interventions, were analysed. In general, interventions were grounded and guided by models and frameworks, and focused on specific subpopulations, or priority groups at increased risk of poorer outcomes. Interventions mixed multiple integrated components. Delivery arrangements targeted more frequently clinical integration (n = 13), and care in proximity, community or online-telephone based (n = 15). Interventions reported investments in the role of users, through self-management support (n = 16), and in coordination, through multidisciplinary teams (n = 9) and continuity of care (n = 8). Implementation strategies targeted educational and training activities (n = 12), and less often, mechanisms of iterative improvement (n = 3). At the level of organizational design and governance, interventions mobilised users and communities through representation, at boards and committees, and through consultancy, along different phases of the design process (n = 11).

Conclusion

The data advance important lessons and considerations to take steps forward from disease-focused care to integrated care at two critical levels: design and implementation. Multidisciplinary work, continuity of care, and meaningful engagement of users seem crucial to attain care that is comprehensive and more proximal, within or cross organizations, or sectors. Promising practices are advanced at the level of design, implementation, and evaluation, that set integration as a continued process of improvement and value professionals and users’ knowledge as assets along those phases.

Trial registration

PROSPERO number CRD42020194117.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The practised universal recommendation for antiretroviral drugs and the transformative power of their effectiveness has put forward interdependent challenges to current health systems, which are now more focused on monitoring side effects from the treatment and preventing age related health problems [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The growing demand and the increasing number of individuals on treatment, pressured by aging and multimorbidity, challenge the systems on how to assure a chronic and continued care approach to People Living with HIV (PLHIV) [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10]. The management burden and system related barriers to access and navigation of services, increases the strain experienced by PLHIV, in addition to the issues of stigma and discrimination still prevalent in our societies [3, 4, 9, 10].

Acknowledging those challenges, the need for new models of care has been growing, and is now widespread at both national and international level [8, 11,12,13]. Health systems, backed by strong community-based resources, have pursued more integrated and people-centred care approaches. They incorporate principles of decentralization and proximity, coordination and flexibility, in order to provide services with more reach, which are adapted to national and local realities as well as evolving needs [1, 5, 14,15,16,17,18]. The main frameworks and models have been endorsed at a supranational level. They are supported by empirical evidence, and are referenced in strategic and health policy documents worldwide [13, 19,20,21]. There are several relevant frameworks and models, such as the chronic care model (CCM), the people-centred and integrated services and care, the shared care model, and the differentiated service delivery model (DSD). Each of these set a strategic structure of principles and mechanisms for responding to changing needs related to HIV and multimorbidity, but are no solution for all problems [16]. Integration and a people-centred organization of care and services should be looked at as dynamic and adaptive process. To maximize their effectiveness, interventions must employ robust implementation and change management strategies [3, 22]. Topics related to how these innovative approaches are put into practice have been emerging as a subject of research [3, 14, 18, 23]. Braithwaite et al. demand intersecting implementation science with complexity science as a means of putting attention on the dynamic properties of systems, and the need to manage multiple forces, variables and influences that interact within the process of change [23].

The International AIDS Society-Lancet Commission on the Future of Global Health and HIV Response, established in 2016, reinforce the real-world question of how [18]. An incremental step-based approach, as well as a learn by doing one, were proclaimed as a strategy to integrate HIV responses with the broader health system. Additionally, some determinants of success were highlighted. On the one hand, the need to preserve various features of the present HIV response, like the quality of care assured and respect for human rights, on the other hand, the need to include new features as participatory mechanisms for community inclusion and engagement in that change process [18]. That participatory element is linked, in the literature, to the identification of improvement opportunities and to the design of interventions, both resulting in access and acceptance gains [3, 8, 22].

Future strategies to reshape organizational models and new responses can be supported by reviewing the available published literature on approaches to integrated services and people-centred care, which describe delivery arrangements in the fields of HIV, multimorbidity, or both, as well as how to manage change and measure their implementation process and effectiveness. Motivated by this, we conducted a systematic review to identify how international trends in organizational models are being incorporated into practice. This focused on how high-income countries respond to PLHIV, multimorbidity, or both, as well as their implementation and evaluation processes. This review is part of a larger project to rethink the contemporary model for responding to PLHIV in the Portuguese context.

Methods

Study design

We aimed to identify models and components of integrated healthcare approaches to PLHIV, multimorbidity, or both, and how these models are evaluated and applied in context. Our focus was not restricted to specific outcomes or to a level of integrated care (micro, meso or macro), rather it was more inclusive by being on models and components of integrated delivery arrangements targeting the complexity of care needs for PLHIV, multimorbidity or both, and the available evidence [24, 25]. Thus, a qualitative and descriptive strategy was adopted to extract data on two main domains: delivery arrangements and implementation strategies.

This systematic review was applied according to the updated preferred items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA 2020) statement [26, 27], which follows a pre-defined protocol approved by the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO), whose identification number is CRD42020194117.

Search strategy

Where applicable, the search strategy followed the PICOS framework (see Table 1). We searched MEDLINE (PubMed), SCOPUS, and Web of Science. The search strategy (see Additional file 1) was applied consistently, though with minor modifications for fulfilling the specific requirements of different databases. Boolean operators were used, linking the three main parts: HIV infection, multimorbidity, and care integration. To ensure the best capture of the empirical evidence related to experiences with integrated healthcare approaches, we conducted searches on a wide variety of terms, which from our previous experience, are used interchangeably. However, we did recognize the relevant conceptual differences between them. Additionally, we searched institutional sites of interest using a simplified search strategy: Joint United Nations Program on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) publications, British HIV Association—HIV Medicine Journal, NICE Evidence, European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) iLibrary, Health Programme Database – European Commission, Institutional Repository for Information Sharing (IRIS) – World Health Organization. Searches were also conducted on the references cited in selected papers in order to expand the literature base and assure a more comprehensive approach to the available evidence.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined and aligned according to the PICOS framework. The inclusion criteria applied: (a) studies published from January 1st, 2011, to July 22nd, 2020, (b) empirical studies describing the design, implementation, and/or evaluation of programmes or interventions intended to integrate care and services at the micro, meso or macro levels, (c) targeting adults living with HIV, multimorbidity, or both, (d) use quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods approaches, and (e) studies from high-income countries (2020 world bank classification) and healthcare systems offering universal coverage or free HIV treatment. The exclusion criteria applied: (a) exclusively targeting individuals < 18 years, (b) theoretical studies focusing only on models or the concept of integrated care without reporting an actual intervention or practice, (c) studies focusing on a single disease approach for diseases other than HIV, (d) studies not written in English, (e) reports, conference abstracts, opinion pieces, editorials, dissertations, and research protocols, as well as (f) biomedicals studies.

Data selection and extraction

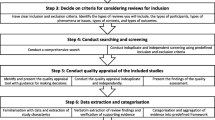

Three researchers (AE, DB, VN) have taken part of the title and abstract screening stage. A complete dual independent review was conducted to identify the relevant articles against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Eligibility criteria were pilot-tested, and no refinements appeared to be required. Where disagreements occurred, the third reviewer, was called in to resolve any issues if no consensus could be reached through discussion.

A second phase of screening was executed independently by two researchers (DB, VN) based on the full-text analysis of the papers previously selected as relevant. We were able to reach a consensus for all divergences and differences of opinion. As such, it was not necessary to call in a third reviewer (AE) to act as arbiter as originally planned. The Rayyan software was used to upload the identified references and to manage the screening phases. This PRISMA flow diagram (see Fig. 1) summarizes the identification and screening phases [27].

Two researchers (DB, VN) extracted data using a standardized form developed for aggregating quality and content analysis (narrative synthesis). The forms were cross-checked by both researchers, and discrepancies were discussed till a consensus could be reached. The Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) taxonomy of health systems interventions (2015) [28] was applied as a framework to extract data, focusing on two domains:

-

(1) Delivery arrangements—changes in how, when and where healthcare is organised and delivered, and who delivers it. This covers four categories: (a) Where care is provided and any changes to the healthcare environment; (b) Who provides the care and how the healthcare workforce is managed; (c) Coordination of care and management of care processes; and (d) Information and communication technology.

-

(2) Implementation strategies—Interventions designed to bring about changes in healthcare organizations, the behaviour of healthcare professionals or the use of health services by healthcare recipients. These cover three categories: (a) Interventions targeted at healthcare organisations; (b) Interventions that target healthcare workers; (c) Interventions targeted at specific types of practice, or conditions; and (d) user and community engagement.

Abstract information also included: the type of study, study design, context, referenced models/theoretical frameworks, primary and secondary objectives, level of integration, dimensions of lessons learned, and the type of measures extracted (see Additional files 2 and 3). Valentijn et al. classification was employed to categorize the level of integration: the macro level – system integration, the meso level – organizational and/or professional integration, and the micro level – clinical integration [25]. Type of measures followed the categorization: (a) process or intermediated outcomes of care – continuity, coordination, patient-centredness, management of lifestyle factors, management of specific diseases, medicine management, (b) use of health services, (c) experience of care and satisfaction, and (d) outcomes of care – patient-reported outcomes and adverse events [29]. An electronic spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) supported the synthesis and analyse of extracted data.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was conducted via a three-step process, applied by two reviewers (DN, VN). The first step is choosing the appropriate categories of studies to appraise. The second is giving an independent score for each criterion, where “met” is classified as “yes”, and “not met” is classified as “no”, while “not enough information” is classified as “can´t tell”. Step three aims to resolve any disagreements via discussion. Procedures were supported by the validated Mixed Method Appraisal Tool ( MMAT) consisting of 19 core criteria in a quality scoring system grouped into five methodological categories [30,31,32,33]. The analysis focused on a detailed presentation of the ratings for each criterion classified as “no” or “can´t tell”, signalling a possible risk of bias, but no studies were excluded based on the degree of assessed quality.

Results

Characteristics of included studies

Our final sample included 30 studies, that underwent the descriptive analysis, corresponding to 22 independent integrated healthcare interventions (see Table 3). Of those, 12 studies on HIV, describing eight interventions, and 18 studies on multimorbidity, describing 14 interventions. Different studies covering the same intervention, offered different perspectives on analysis, from the implementation process to the evaluation of results, with different methodological approaches, and following the same or a different time interval. One study described an experience of multiple settings applying a common framework, across six European regions. It is called the CareWell Program [34].

Eligible interventions came from 13 different geographical locations. Spain (n = 6) and Canada (n = 4) had the highest number of initiatives (see Table 2). Integrated initiatives on HIV were reported in higher number from Australia (n = 2), and on multimorbidity from Spain (n = 5).

Different types of studies were identified, and the quantitative approaches prevailed in frequency (n = 22), over the qualitative (n = 4), and mixed methods approaches (n = 4) (see Table 2). Quantitative approaches focused on evaluating the effect of an intervention, compared to treatment as usual or with a pre and post-intervention design. Mixed methods approaches brought the perspectives of health care teams and users to the evaluation process. Qualitative approaches focused most on the processes of intervention design and change management, exploring the identification of factors that could hinder or promote more successful interventions, and of areas for optimization (see Additional file 2).

Overview of integrated approaches

Overall, interventions were grounded and guided by models and frameworks, conceptual and/or empirical based (n = 18), exception made to four studies that do not make that information available (see Table 3).

Approaches responding to the challenges and complexity of chronic diseases, such as the chronic care model (n = 6) [36,37,38, 50, 52, 53, 58, 59] the chronic disease self-management model (n = 4) [40, 55, 58, 61], and the Kaiser Permanente model (n = 1) were more frequently reported [42]. Along with those, holistic approaches, patient, client, or person-centred care models were identified as a main guidance for developing interventions (n = 6) [35, 37, 38, 41, 43, 44, 50,51,52,53]. Complementarily, some interventions applied mechanisms of change supported by theoretical approaches, such as behaviour change theories (n = 6) [40, 55,56,57,58, 62, 63]. Less often, frameworks and models guiding the complex change process were identified. They offered a structure that promote system-level thinking and participatory approaches. Two interventions on HIV used the Precede-proceed model (n = 2) [58, 62, 63]. Three interventions on multimorbidity reported using frameworks and models with that purpose, the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) complex intervention development framework (n = 2) [40, 43, 44] and the International Association for Public Participation (IAP2) framework (n = 1) [37, 38].

Interventions mainly described initiatives targeting the primary process of care delivery (micro level) (n = 13). These initiatives were anchored in the introduction of more holistic approaches, the expansion of narrower disease-focused guidelines and the reinforcement of the role of individuals as co-creators in the care process (see Table 3). Self-management programs, case management programs, and individual multidisciplinary care plans are some examples of these initiatives.

Eleven interventions were identified at the meso-level, anchored in building professional partnerships, within or across organisations (n = 9), and/or in building inter-organizational relationships (n = 6), either supported by hierarchical or network-like governance mechanisms.

Interventions combining different levels and dimensions of integration were identified. Combining the micro and meso level (professional) there were one intervention, and the dimensions of professional and organizational integration there were five interventions. Initiatives at the micro level were more frequent than other levels on multimorbidity interventions (n = 9), in the case of HIV interventions, initiatives at the micro and meso level were equally frequent (n = 4).

Delivery arrangements and implementation strategies

Common to most studies, interventions described care in proximity through primary care, community care, online or telephone-based care (n = 15) (see Table 3). They invested in the role of users, their empowerment and capacity-building to self-manage health and well-being (n = 17); as well as in care coordination and the management process, by building and delivering care through multidisciplinary teams (n = 9) within or across organisations, and continuity of care (n = 8) (see Table 4). These investments had a point in common. That is, they were supported by enhanced communication between healthcare teams as well as between professionals and users. Also, these investments had a point of difference between HIV and multimorbidity interventions, which is expressed by the role assigned to primary care in endorsing solutions for proximity and continuity of care. HIV interventions were backed by strong community-based and hospital-based resources, rather than primary care-based resources.

Delivery arrangements mixed multiple integrated components per intervention. The dimension of care coordination and management process totalized 29 components among 16 independent interventions, and the dimension of who provides care, 21 elements among 18 independent interventions (see Table 4).

Information and communication technologies were predominantly used to support delivery management of integrated care processes, through technology-based methods and tools to transfer and share healthcare information and support care (n = 8). Examples put into practice enablers that support key functions and activities for multidisciplinary collaboration, continuity of care, shared decision making and empowerment of PLHIV, or multimorbidity. These were realized via information and communication technology platforms, communication channels, standard electronic communication and discharge routines, electronic data entry templates, shared personal health folders, and computerized decision support systems.

Strategies directed to support effective change are commonly described as investments in education and training activities (n = 9), and less often, as mechanisms of iterative and continuous approaches to reviewing and improving transformation (n = 3). Ten of the 22 interventions described were pilot tested as a strategy to optimize and refine interventions, or as a trial for scaling up. Two of these were on HIV (see Table 3).

Generally, interventions focused on specific subpopulations, or priority groups at increased risk of poorer outcomes, rather than a population-based approach. A range of inclusion or exclusion criteria were applied. On HIV, three studies broadly approached people who were HIV infected, while the other nine interventions looked at specific subpopulations of PLHIV, such as persons who inject drugs, men who have sex with men, or other priority groups. This was accomplished via matched criteria, such as being HIV infected with complex clinical management issues (see Table 3). Variation between the criteria applied to the definition of multimorbidity was also identified. Interventions commonly applied the counting criteria with different cut-off points, either two or more, or three or more, combined chronic conditions. The criterion of age was used to restrict interventions to older populations, 60 or 65 years or older (n = 5), or from older populations (n = 2). Combined criteria were used to target individuals with more complex cases, needing a more intense allocation of resources and support in managing their health (n = 10), such as higher severity, vulnerability, higher risk of hospitalization, and social complexity.

Collaborative processes—users and community engagement

Results profiled interventions supporting and promoting collaborative processes at the level of direct care delivery (n = 17) and the organizational design and governance level (n = 11) (see Table 4). At the level of direct care delivery three cross-cutting approaches were identified: 1) promoting and activating user skills for self-management (capacity building), 2) investing in tools and techniques for co-creation and shared decision-making with healthcare professionals (informing decisions), and 3) processes of trust-building within the relationship (strengthening relationships). At the level of organizational design and governance, users and community engagement followed two approaches, one where they performed as equal partners in planning and quality processes, by representation at boards, and committees, and the other where they performed as consultants, in needs assessment, validation processes, evaluation, and optimising interventions. The engagement arrangements designed were mainly based on samples of impacted people, where citizens more than stakeholders play an active role. These were on-site based and supported by deliberative processes.

HIV studies reported four independent interventions [36, 58, 60, 62, 63] combining direct care delivery, and organizational design and governance mechanisms, while for multimorbidity, there were seven [37, 38, 43,44,45, 50, 52,53,54, 61]. Solely targeting the level of direct care delivery, HIV reported two interventions [46, 47, 56, 57] and multimorbidity, four [40, 41, 51, 55].

Measures and indicators reported

Generally, results-focused data were collected at the individual level, and measures and indicators reported cover different domains, from process to outcomes of care. At the level of the domains reported there were variations between HIV and multimorbidity studies (see Table 5). HIV studies focused on disease-specific measures related to disease management and medicines management, such as antiretroviral therapy uptake and viral load suppression. Multimorbidity studies focused on patient-centredness measures, such as patient activation, self-efficacy, and individualised goal attainment. Multimorbidity studies also focused on use of health services measures (n = 13), such as emergency room visits, unplanned admissions, length of stay due to unplanned admissions; and outcomes of care (n = 13), mainly patient-reported outcome measures (PROM), such as health-related quality of life and functional status. HIV studies also invested in measuring outcomes of care (n = 7), like HIV-related quality-of-life and mortality/survival rates.

Discussion

This review summarized the empirical evidence published around approaches of integrated healthcare services for PLHIV, multimorbidity, or both. It focuses on the description of interventions, their implementation process and effectiveness measures.

Both points of difference and points of consensus were found in trends between interventions on HIV and on multimorbidity. Differences may represent divergences or varying rates of advance for integration. Two main differences were identified between HIV and multimorbidity interventions. For one, the role assigned to primary care in endorsing solutions for proximity and continuity of care. As to the other, the primacy attributed to measures and indicators monitoring and evaluating the care process, as well as the balance between disease specific and generic measures. Multimorbidity interventions assigned primacy to generic measures of the care process more in alignment with the vision of person-centred and integrated services and care. HIV studies focused on disease-specific measures related to disease management and medicines management.

Even though there are some points of difference in trends between HIV and multimorbidity interventions, consensus seem to prevail between strategies to attain integrated and people-centred services and care. From that, the data advance important considerations to take steps forward from disease or patient-focused care to integrated and people-centred care in response to the evolving needs and challenges of PLHIV throughout their life cycle. The analysis of the 30 studies that cover a total of 22 independent interventions support a discussion around three main themes: 1) delivery arrangements – levels and components implemented; 2) implementation processes – mechanisms and strategies implemented; and 3) coproduction – the role of users and communities, and mechanisms implemented.

Delivery arrangements

Overall, results focus on the proximity and fluidity of care and services, bringing solutions closer to users, and targeting clinical integration, to overcome the paradigm of a disease-focused approach. When arrangements surpass the micro level or crosscut levels, interconnections and interdependencies reinforce the challenges associated to the change management process and the governance mechanisms putted into practice. The literature highlight complexity in relation to the challenges posed to professional and organizational integration, in terms of effectiveness and sustainability [24, 25]. Integration consistency should be built upon common ground: a shared paradigm of care and language, competencies, roles, responsibilities; and upon common governance, accountability and trust [24, 25, 64]. In support of that common ground, frameworks and models seem to play an important role, by guiding a shared philosophy of care, practice, and language, and structuring collaborative work for teams, including competencies, functions, and accountability.

Delivery arrangements evidenced a combination of multiple components per intervention, such as the building blocks for integration. Multidisciplinary collaboration, continuity of care and meaningful participation of users seem crucial for comprehensive and more proximal care, established within an organization, cross organizations, or cross sectors. That pattern seems to be in alignment with studies targeting the state of the art of people-centred and integrated services and care for PLHIV or multimorbidity, applying methodological approaches, which may be closer or more distant [7, 13, 65]. Some evidence related to context specificity and the organic emergence of local solutions highlight particular challenges connected to HIV, such as stigma, confidentiality concerns and minimum case load, that should be taken into account at the level of design, implementation and evaluation of integrated healthcare approaches [13, 20, 22].

Data converge with European results reporting higher investments in technology-based methods to transfer healthcare information and support the delivery of care [65]. The tools and elements in our data that were not reported on as often, such as smart home technologies [34] and telemedicine [41], were specially reinforced and tested in relation to the experience of the covid-19 pandemic [66,67,68]. This has the potential to enable access and proximity of services, as well as comprehensive care and empowerment of users.

Implementation processes

Interventions reflect complexity, as a characteristic of the integrated healthcare approaches described, and as a feature of the context in which they are embedded. Acknowledging that assumption seems to impact the design, implementation, and research processes inherent to integrated healthcare approaches [23, 69,70,71].

Under that paradigm, Reed et al. set three main principles to guide practice and research: act scientifically and pragmatically, embrace complexity, and engage and empower [71]. Initiatives and mechanisms employed in the interventions under analysis crosscut those principles.

Near half of the approaches were grounded by a triangulation of conceptual basis, the available evidence, and the perspectives of professionals, the community and users, to attain a more context-specific problem-solving integrated approach [34, 36, 37, 43, 50, 52, 54, 56, 58, 60,61,62]. Strategies to adapt to system responses and generated learning were identified. Pilot testing was a common strategy linked to optimization and refinement of interventions [34, 38, 40, 41, 44, 56, 59,60,61,62]. Less commonly, continued improvement mechanisms [36, 50], and iterative monitoring delivery performance mechanisms were described [52]. Qualitative approaches were applied to deeply understand implementation processes [43, 53, 59, 61].

Multimorbidity approaches attributed primacy to the care process, through generic measures, more in alignment with the vision of person-centred and integrated services and care than HIV approaches. Both HIV and multimorbidity studies, invested in measure patient-reported outcomes, HIV-related, or generic, respectively. The perspective of users may contribute to decisions and actions acquainted with and linked to the vision of person-centred and integrated approaches, but may also work to empower users by making their preferences and needs heard [8, 72].

Overall, interventions recognised the agency power of the actors involved, from the side of supply to the side of demand. Meaningful engagement of users and professionals were reported [36, 43, 58, 59, 61], and support dedicated to opportunity and resources for that engagement were described [44, 45, 53, 61].

Coproduction

Our empirical data on engagement of users and communities transverse a basis of partnership, shared decision-making, and commitment between all the participants, at the level of direct care delivery and at the level of organizational design and governance. Those activities were supported by tools, behavioural techniques, and participatory mechanisms.

The relation between the compromise of engagement and the value created by it is discussed in the literature [73,74,75]. Direct, instrumental value is recognized by organizations as efficiency, effectiveness, and innovation; and by citizens as satisfaction, need fulfilment, and empowerment. The identified experiences of user engagement echoed this association [37, 38, 40, 41, 44, 50, 58, 61]. The literature also recognises a societal value, through social learning, and by promoting a culture change at the organizational and citizenship levels [73].

That literature matches different levels of engagement intensity, information exchange practices and weight of influence to more discrete or structural outcomes in service redesign [74]. More discrete products, such as educational or tool development, informed policy or planning documents, are associated with consultative unidirectional feedback experiences. More structural outcomes, such as enhanced care processes or service delivery and governance, are associated with highly collaborative engagement experiences, such as co-design and partnership strategies [74]. Both mechanisms were identified in the analysis, either as consultative mechanisms [44, 45, 53, 58, 61,62,63] or as highly collaborative mechanisms [36,37,38, 50].

In the literature, that association is mediated by contextual factors that qualify user participation during the phases of design, delivery, and evaluation. These factors interact with strategies of engagement design and sampling [74, 75]. The set of the most common strategies associated with optimal engagement was identified. Making use of deliberative spaces, external facilitation, including users in all phases of the process, flexible approaches to engagement, user training, clarity of roles and objectives, offering feedback, leadership by local champions, institutional and executive-level commitment, dedicated resources from local authorities, and continued contact with management and executives [74]. Leadership seems key, but some authors signal a rise in clinician and community-led initiatives [74]. Time opportunity is also critical for meaningful engagement and should be considered when designing participatory mechanisms [74, 75].

Practical lessons for designing, implementing and evaluating integrated care approaches

Results underlined two interdependent points for practical lessons, including methodological issues related to the scope of complex interventions research, their design, and evaluative strategy; as well as change management and implementation issues, related to the conceptualization of healthcare as a complex and adaptative system (see Additional file 3). Their elicitation recognizes that effectiveness can be impacted by intervention and by implementation deficiencies and failures.

Methodologically, the risks and biases highlighted can inform effective future integrated approaches. Results support the idea that interventions may not be suitable for all targeted individuals, and may not be effective in all contexts, highlighting the need to stratify interventions or adapt models to subpopulations and sub-groups specificities and consider sub-group analysis [35, 36, 42, 44, 47, 50,51,52, 54, 55]. Results also show that changes can be small and take a long time to show or reflect confounding effects, highlighting the need to determine the length of follow-up by weighing the rate and pattern of change, pondering the effect of the natural history of morbidity, and learning effects [39, 40, 45, 57, 62, 63]. Strategies need to consistently align the model of care with the underlying processes, the selected quality constructs, and their operationalization, resulting in measures that are robust in detecting and guiding change [36, 52, 60, 61]. Also, acknowledging interventions as a realm of variation in the number and combination of components and levels of integration, in the extent of behaviours targeted, in the required expertise and skills to perform accordingly, and in the number of practices and settings involved, adopting a whole practice approach in evaluation should be considered [45, 53].

Change management and implementation issues highlight the impact of the underlying organizational, social, political, and economic dimensions acting in the intervention context, and by that, strengthen the value of research dedicated to those processes [53, 58,59,60,61]. Investing in research for those processes produced evidence with regards to modifiable conditions linked to the success of interventions, impacting acceptancy, feasibility, scalability, and transferability across contexts [53, 61, 62]. Co-design strategies were implemented for developing and optimizing interventions in partnership with all key actors and stakeholders [37, 38, 43, 44, 58]. As enablers of a transformative environment at the practice level, they put education, training, and quality improvement tools into place [34]. Mechanisms to balance high fidelity to intervention design with adaptability to local conditions, were applied in some of the interventions under analysis, and should be putted into practice[34, 36, 53].

Limitations of the study

The review covered a 10-year period, identifying and selecting studies published between January 2011 and July 2020. The timeframe was set to a realistic interval to capture trends and illustrate changes related to the assimilation of chronicity into the language of HIV, and translation into integrated and people-centred models of care.

Aware of the potential limitation from not searching in Embase associated to PubMed, due to its unavailability, a search strategy was defined in conjunction with a librarian to mitigate this limitation. The strategy includes the use of three databases, along with an enlarging the range of nomenclature considered (to reach a greater percentage of available citations and journals).

Even after employing that wide search strategy, the evidence for trends related to organizational models in high-income countries seem scarce. The topic cross boundaries for different disciplines and some alternative nomenclature may not have been considered or the lack of publishing in scientific journals may exert some influence [2, 76]. Also, the boundaries set by the inclusion and exclusion criteria may have contributed to the small number of eligible studies.

Even though the authors believe that results reflect the reality of the published integrated approaches targeting HIV and multimorbidity, which is in alignment with the objective for this review.

The level of disagreement between the reviewers was measured by the inter-rater agreement, with a value of 98,4%.

Conclusion

Even with some points of difference in trends between HIV and multimorbidity interventions, the data advance important considerations to take steps forward from disease or patient-focused care, to integrated and people-centred care, in response to the evolving needs and challenges of PLHIV throughout their life cycle. Lessons learned focus initiatives at two critical levels: design and implementation.

Overall, results focus on the proximity and fluidity of care and services, bringing solutions closer to users and community facilities around clinical integration. Delivery arrangements mixed multiple elements per initiative, as building blocks for integration. Multidisciplinary collaboration, continuity of care and meaningful engagement of users seem crucial to attain comprehensive and more proximal care, within or across organizations, or sectors.

Interventions advance promising practices at the level of design, implementation, and evaluation, that set integration as a continued process of improvement and value professionals and users’ knowledge as assets along those phases.

Further research related to the conditions and strategies that work effectively for transformational change, sustained improvement, and scalability of people centred and integrated care is recommended in real-world conditions.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated or analysed that support the findings of this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files. Any other data or materials are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request (VN: vnicolau@ensp.unl.pt).

References

Roy M, Bolton Moore C, Sikazwe I, Holmes CB. A Review of Differentiated Service Delivery for HIV Treatment: Effectiveness, Mechanisms, Targeting, and Scale. Vol. 16, Current HIV/AIDS Reports. Current Medicine Group LLC 1; 2019 324–34. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31230342/. Cited 16 Feb 2021

Mapp F, Hutchinson J, Estcourt C. A systematic review of contemporary models of shared HIV care and HIV in primary care in high-income settings. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(14):991–7. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25804421/. Cited 23 Jul 2021.

Schiøtz ML, Høst D, Frølich A. Involving patients with multimorbidity in service planning: perspectives on continuity and care coordination. J comorbidity. 2016;6(2):95–102. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29090180/. Cited 21 Jul 2022

d’Arminio Monforte A, Bonnet F, Bucher HC, Pourcher V, Pantazis N, Pelchen-Matthews A, et al. What do the changing patterns of comorbidity burden in people living with HIV mean for long-term management? Perspectives from European HIV cohorts, HIV Medicine. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2020 21;3–16. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32881311/. Cited 8 Jun 2021

Rodriguez KM, Khalili J, Trevillyan J, Currier J. What is the best model for HIV primary care? Assessing the influence of provider type on outcomes of chronic comorbidities in HIV infection. J Infect Dis Oxford University Press. 2018;218:337–9 (Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6927866/. Cited 17 Jun 2021).

Watt N, Sigfrid L, Legido-Quigley H, Hogarth S, Maimaris W, Otero-Garcıa L, et al. Health systems facilitators and barriers to the integration of HIV and chronic disease services: A systematic review, Health Policy and Planning. Oxford University Press; 2017 32;iv13–26. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28666336/. Cited 16 Feb 2021

Liddy C, Shoemaker ES, Crowe L, Boucher LM, Rourke SB, Rosenes R, et al. How the delivery of HIV care in Canada aligns with the Chronic care model: A qualitative study. PLoS One. 2019;14(7):0220516.

Lazarus JV, Safreed-Harmon K, Kamarulzaman A, Anderson J, Leite RB, Behrens G, et al. Consensus statement on the role of health systems in advancing the long-term well-being of people living with HIV. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):4450 (Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8285468/. Cited 19 Jul 2022).

Engelhard EAN, Smit C, Van Dijk PR, Kuijper TM, Wermeling PR, Weel AE, et al. Health-related quality of life of people with HIV: An assessment of patient related factors and comparison with other chronic diseases. AIDS. 2018;32(1):103–12.

Yang HY, Beymer MR, Suen-Chuan S. Chronic disease onset among people living with HIV and AIDS in a large private insurance claims dataset. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):18514 (Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC6897968/. Cited 19 Jul 2022).

Kendall CE, Wong J, Taljaard M, Glazier RH, Hogg W, Younger J, et al. A cross-sectional, population-based study of HIV physicians and outpatient health care use by people with HIV in Ontario. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25884964/. Cited 23 Jul 2021.

Kendall CE, Manuel DG, Younger J, Hogg W, Glazier RH, Taljaard M. A population-based study evaluating family physicians’ HIV experience and care of people living with HIV in Ontario. Ann Fam Med 2015;13(5):436–45. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26371264/. Cited 23 Jul 2021.

Mapp F, Hutchinson J, Estcourt C. A systematic review of contemporary models of shared HIV care and HIV in primary care in high-income settings International Journal of STD and AIDS. SAGE Publications Ltd; 2015 26;991–7. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/https://doi.org/10.1177/0956462415577496Cited 8 Jun 2021

Duffy M, Ojikutu B, Andrian S, Sohng E, Minior T, Hirschhorn LR. Non-communicable diseases and HIV care and treatment: models of integrated service delivery. Tropical Medicine and International Health. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2017 22;926–37. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28544500/Cited 18 Jun 2021

Leblanc NM, Albuja L, Desantis J. The uses of self and space: Health providers’ approaches to engaging patients into the HIV care continuum. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(8):321–9. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30067407/Cited 16 Feb 2021

Geng EH, Holmes CB. Research to improve differentiated hiv service delivery interventions: Learning to learn as we do. PLoS Medicine. Public Library of Science; 2019 16. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31112546/Cited 9 Jun 2021

Duncombe C, Rosenblum S, Hellmann N, Holmes C, Wilkinson L, Biot M, et al. Reframing HIV care: Putting people at the centre of antiretroviral delivery. Tropical Medicine and International Health. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2015 20;430–47. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12460Cited 14 Jun 2021

Bekker LG, Alleyne G, Baral S, Cepeda J, Daskalakis D, Dowdy D, et al. Advancing global health and strengthening the HIV response in the era of the Sustainable Development Goals: the International AIDS Society—Lancet Commission, The Lancet. Lancet Publishing Group; 2018 392;312–58. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30032975/Cited 17 Jun 2021

Abdelhalim R, Grudniewicz A, Kuluski K, Wodchis W. A roadmap to assess patient experience with person-centered integrated care: when, what and how? Int J Integr Care. 2019;19(4):420. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.s3420Cited 7 Oct 2021

Hutchinson J, Sutcliffe LJ, Williams AJ, Estcourt CS. Developing new models of shared primary and specialist HIV care in the UK: a survey of current practice. Int J STD AIDS. 2016;27(8):617–24. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26113516/Cited 9 Jun 2021

World Health Organization. WHO global strategy on people-centred and integrated health services: interim report. 2015. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/155002Cited 16 Aug 2022

Kendall CE, Shoemaker ES, Boucher L, Rolfe DE, Crowe L, Becker M, et al. The organizational attributes of HIV care delivery models in Canada: A cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0199395. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0199395Cited 9 Jun 2021

Braithwaite J, Churruca K, Long JC, Ellis LA, Herkes J. When complexity science meets implementation science: a theoretical and empirical analysis of systems change. BMC Med 2018;16(1):1–14. Available from: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1057-zCited 23 Sep 2021

Valentijn PP. Rainbow of Chaos: A study into the Theory and Practice of Integrated Primary Care. Int J Integr Care. 2016 16(2);195. Available from: http://www.ijic.org/articles/https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.2465/Cited 9 Dec 2021

Valentijn PP, Schepman SM, Opheij W, Bruijnzeels MA. Understanding integrated care: a comprehensive conceptual framework based on the integrative functions of primary care. Int J Integr Care. 2013;13(JANUARY-MARCH 2):e010 (Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3653278/).Cited 8 Dec 2021

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ. BMJ Publishing Group; 2021 372. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33782057/Cited 11 Jun 2021

Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. The BMJ. BMJ Publishing Group; 2021 372. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160Cited 29 Jun 2021

EPOC Taxonomy | Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care. Available from: https://epoc.cochrane.org/epoc-taxonomyCited 13 Dec 2021

Valderas JM, Gangannagaripalli J, Nolte E, Boyd CM, Roland M, Sarria-Santamera A, et al. Quality of care assessment for people with multimorbidity. J Intern Med. 2019;285(3):289–300.

Guise JM, Chang C, Viswanathan M, Glick S, Treadwell J, Umscheid CA, et al. Agency for healthcare research and quality evidence-based practice center methods for systematically reviewing complex multicomponent health care interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(11):1181–91.

Petticrew M, Rehfuess E, Noyes J, Higgins JPT, Mayhew A, Pantoja T, et al. Synthesizing evidence on complex interventions: how meta-analytical, qualitative, and mixed-method approaches can contribute. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(11):1230–43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/23953082/Cited 23 Dec 2021

Campbell M, McKenzie JE, Sowden A, Katikireddi SV, Brennan SE, Ellis S, et al. Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: reporting guideline. BMJ. 2020;368:l6890 Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC7190266/.

Hong QN, Fàbregues S, Bartlett G, Boardman F, Cargo M, Dagenais P, et al. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ Inf. 2018;34(4):285–91.

Mateo-Abad M, Fullaondo A, Merino M, Gris S, Marchet F, Avolio F, et al. Impact Assessment of an Innovative Integrated Care Model for Older Complex Patients with Multimorbidity: The CareWell Project. Int J Integr Care. 2020;20(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32477037/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Ko NY, Lai YY, Liu HY, Lee HC, Chang CM, Lee NY, et al. Impact of the nurse-led case management program with retention in care on mortality among people with HIV-1 infection: a prospective cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2012;49(6):656–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22269137/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Tu D, Belda P, Littlejohn D, Pedersen JS, Valle-Rivera J, Tyndall M, et al. Adoption of the chronic care model to improve HIV care in a marginalized, largely aboriginal population. Can Fam Phys • Le Médecin Fam Can |. 2013;59:650–7.

Sampalli T, Dickson R, Hayden J, Edwards L, Salunkhe A. Meeting the needs of a complex population: a functional health- and patient-centered approach to managing multimorbidity. J comorbidity. 2016;6(2):76–84. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29090178/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Sampalli T, Fox RA, Dickson R, Fox J. Proposed model of integrated care to improve health outcomes for individuals with multimorbidities. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2012;6:757–64 Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC3484525/.

Tortajada S, Giménez-Campos MS, Villar-López J, Faubel-Cava R, Donat-Castelló L, Valdivieso-Martínez B, et al. Case Management for Patients with Complex Multimorbidity: Development and Validation of a Coordinated Intervention between Primary and Hospital Care. Int J Integr Care. 2017;17(2). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28970745/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Garvey J, Connolly D, Boland F, Smith SM. OPTIMAL, an occupational therapy led self-management support programme for people with multimorbidity in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25962515/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Pariser P, Thuy-Nga T, Brown JB, Stewart M, Charles J. Connecting People With Multimorbidity to Interprofessional Teams Using Telemedicine. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(Suppl 1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31405877/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Lanzeta I, Mar J, Arrospide A. Cost-utility analysis of an integrated care model for multimorbid patients based on a clinical trial. Gac Sanit. 2016;30(5):352–8. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27372221/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Mercer SW, Fitzpatrick B, Guthrie B, Fenwick E, Grieve E, Lawson K, et al. The CARE Plus study - a whole-system intervention to improve quality of life of primary care patients with multimorbidity in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation: exploratory cluster randomised controlled trial and cost-utility analysis. BMC Med. 2016;14(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27328975/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Mercer SW, O’brien R, Fitzpatrick B, Higgins M, Guthrie B, Watt G, et al. The development and optimisation of a primary care-based whole system complex intervention (CARE Plus) for patients with multimorbidity living in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation. Chronic Illn. 2016;12(3):165–81. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27068113/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Mateo-Abad M, González N, Fullaondo A, Merino M, Azkargorta L, Giné A, et al. Impact of the CareWell integrated care model for older patients with multimorbidity: a quasi-experimental controlled study in the Basque Country. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32620116/cited 6 Aug 2022

Vallecillo G, Mojal S, Roquer A, Samos P, Luque S, Martinez D, et al. Low Non-structured Antiretroviral Therapy Interruptions in HIV-Infected Persons Who Inject Drugs Receiving Multidisciplinary Comprehensive HIV Care at an Outpatient Drug Abuse Treatment Center. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(5):1068–75. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26427376/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Vallecillo G, Fonseca F, Marín G, Castillo C, Dinamarca F, Durán X, et al. Reaching the 90–90–90 UNAIDS treatment target for people who inject drugs receiving integrated clinical care at a drug-use outpatient treatment facility. J Public Heal 2020 302. 2020;30(2):481–6. Available from: https://link.springer.com/article/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-020-01298-9Cited 6 Aug 2022

Psichogiou M, Giallouros G, Pantavou K, Pavlitina E, Papadopoulou M, Williams LD, et al. Identifying, linking, and treating people who inject drugs and were recently infected with HIV in the context of a network-based intervention. AIDS Care. 2019;31(11):1376–83. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30939897/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Nikolopoulos GK, Pavlitina E, Muth SQ, Schneider J, Psichogiou M, Williams LD, et al. A network intervention that locates and intervenes with recently HIV-infected persons: The Transmission Reduction Intervention Project (TRIP). Sci Rep. 2016;6:38100.

Berntsen GKR, Dalbakk M, Hurley JS, Bergmo T, Solbakken B, Spansvoll L, et al. Person-centred, integrated and pro-active care for multi-morbid elderly with advanced care needs: A propensity score-matched controlled trial. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):682.

Elston J, Gradinger F, Asthana S, Lilley-Woolnough C, Wroe S, Harman H, et al. Does a social prescribing “holistic” link-worker for older people with complex, multimorbidity improve well-being and frailty and reduce health and social care use and costs? A 12-month before-and-after evaluation. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2019;20:e135. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31547895/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Salisbury C, Man MS, Bower P, Guthrie B, Chaplin K, Gaunt DM, et al. Management of multimorbidity using a patient-centred care model: a pragmatic cluster-randomised trial of the 3D approach. Lancet. 2018;392(10141):41–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31308-4. Cited 2021 Feb 23.

Mann C, Shaw ARG, Guthrie B, Wye L, Man MS, Chaplin K, et al. Can implementation failure or intervention failure explain the result of the 3D multimorbidity trial in general practice: Mixed-methods process evaluation. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e031438.

Panagioti M, Reeves D, Meacock R, Parkinson B, Lovell K, Hann M, et al. Is telephone health coaching a useful population health strategy for supporting older people with multimorbidity? An evaluation of reach, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness using a “trial within a cohort.” BMC Med. 2018;16(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29843795/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Reed RL, Roeger L, Howard S, Oliver-Baxter JM, Battersby MW, Bond M, et al. A self-management support program for older Australians with multiple chronic conditions: a randomised controlled trial. Med J Aust. 2018;208(2):69–74. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29385967/cited 6 Aug 2022

de Bruin M, Oberjé EJM, Viechtbauer W, Nobel HE, Hiligsmann M, van Nieuwkoop C, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a nurse-delivered intervention to improve adherence to treatment for HIV: a pragmatic, multicentre, open-label, randomised clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17(6):595–604.

Wijnen BFM, Oberjé EJM, Evers SMAA, Prins JM, Nobel HE, Van Nieuwkoop C, et al. Cost-effectiveness and Cost-utility of the Adherence Improving Self-management Strategy in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Care: A Trial-based Economic Evaluation. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68(4):658–67. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30239629/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Millard T, Dodson S, McDonald K, Klassen KM, Osborne RH, Battersby MW, et al. The systematic development of a complex intervention: HealthMap, an online self-management support program for people with HIV. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30509195/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Jauregui ML, Silvestre C, Valdes P, Gaminde I. Qualitative Evaluation of the Implementation of an Integrated Care Delivery Model for Chronic Patients with Multi-Morbidity in the Basque Country. Int J Integr Care. 2016;16(3). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28435420/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Anglada-Martínez H, Martin-Conde M, Rovira-Illamola M, Sotoca-Momblona JM, Sequeira E, Aragunde V, et al. Feasibility and Preliminary Outcomes of a Web and Smartphone-Based Medication Self-Management Platform for Chronically Ill Patients. J Med Syst. 2016;40(4):1–14. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26872781/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Irfan Khan A, Gill A, Cott C, Hans PK, Steele Gray C. mHealth tools for the self-management of patients with multimorbidity in primary care settings: Pilot study to explore user experience. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2018;6(8). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30154073/Cited 19 Feb 2021

Millard T, Mcdonald K, Girdler S, Slavin S, Elliot J. Online self-management for gay men living with HIV: a pilot study. Sex Health. 2015;12(4):308–14. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26093540/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Millard T, Agius PA, McDonald K, Slavin S, Girdler S, Elliott JH. The Positive Outlook Study: A Randomised Controlled Trial Evaluating Online Self-Management for HIV Positive Gay Men. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(9):1907–18. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26896121/Cited 6 Aug 2022

Charles A, Wenzel L, Kershaw M, et al. A year of integrated care systems: reviewing the journey so far. London: The King´s Fund; https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/sites/default/files/2018-09/Year-of-integrated-care-systems-reviewing-journey-so-far-full-report.pdf. 2018. Accessed 3 Aug 2022.

Melchiorre MG, Papa R, Rijken M, van Ginneken E, Hujala A, Barbabella F. eHealth in integrated care programs for people with multimorbidity in Europe: Insights from the ICARE4EU project. Health Policy (New York). 2018;122(1):53–63. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28899575/Cited 19 Feb 2021

Guaraldi G, Milic J, Martinez E, Kamarulzaman A, Mussini C, Waters L, et al. Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) Care Models During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Era. Clin Infect Dis. 2021;73(5):e1222–7. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/34492689Cited 13 Sept. 2022

Harsono D, Deng Y, Chung S, Barakat LA, Friedland G, Meyer JP, et al. Experiences with telemedicine for HIV care during the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods study. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(6):2099 Available from: /pmc/articles/PMC8782707/. Cited 23 Sep 2022.

Smith E, Badowski ME. Telemedicine for HIV Care: Current Status and Future Prospects. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2021;13:651–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34140812/Cited 23 Sept. 2022

Skivington K, Matthews L, Simpson SA, Craig P, Baird J, Blazeby JM, et al. A new framework for developing and evaluating complex interventions: update of Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ. 2021;374. Available from: https://www.bmj.com/content/374/bmj.n2061Cited 25 May 2022

Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018;16(1). Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29921272/Cited 3 Aug 2022

Reed JE, Howe C, Doyle C, Bell D. Simple rules for evidence translation in complex systems: A qualitative study. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):1–20. Available from: https://bmcmedicine.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1076-9Cited 3 Aug 2022

Wells S, McLean J. One way forward to beat the newtonian habit with a complexity perspective on organisational change. Systems. 2013;1(4):66–84.

Nabatchi T, Sancino A, Sicilia M. Varieties of Participation in Public Services: The Who, When, and What of Coproduction. Public Adm Rev. 2017;77(5):766–76. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/315912107_Varieties_of_Participation_in_Public_Services_The_Who_When_and_What_of_CoproductionCited 15 Jan 2022

Bombard Y, Baker GR, Orlando E, Fancott C, Bhatia P, Casalino S, et al. Engaging patients to improve quality of care: a systematic review. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):98. Available from: https://implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-018-0784-zCited 23 Jun 2021

Bobbio L. Designing effective public participation. Policy Soc. 2019;38(1):41–57. Available from: https://doaj.org/article/c3d3818b66f44b5d87059f7777577325Cited 23 Jun 2022

van der Heide I, Snoeijs S, Quattrini S, Struckmann V, Hujala A, Schellevis F, et al. Patient-centeredness of integrated care programs for people with multimorbidity. Results from the European ICARE4EU project. Health Policy. 2018;122(1):36–43. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29129270/. Cited 16 Sept 2021.

Acknowledgements

We thank Isabel Andrade for providing bibliographic support.

Funding

The systematic review was conducted as part of the project “Financiamento do VIH no continuum do percurso da pessoa com doença” [HIV financing in the continuum of the care path of the person with disease”] funded by the Gilead Sciences, Inc. The present publication was funded by Fundação Ciência e Tecnologia, IP national support through CHRC (UIDP/04923/2020).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VN, DB, TR and AE conceptualized the study and developed the research protocol. VN, DB and AE identified articles for full-text review. VN and DB extracted data from studies that met the inclusion criteria. VN synthesized and analysed the data. VN wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed comments to finalise the manuscript and approved the final submitted version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Search strategy detailing.

Additional file 2.

Summary of abstracted data per study: geographical location and characteristics of studies.

Additional file 3.

Summary of abstracted data per study: intervention design, implementation strategies, measures reported and lessons learned.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nicolau, V., Brandão, D., Rua, T. et al. Organisation and integrated healthcare approaches for people living with HIV, multimorbidity, or both: a systematic review. BMC Public Health 23, 1579 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16485-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16485-y