Abstract

Background

Racial and ethnic inequalities in all-cause mortality exist, and individual-level lifestyle factors have been proposed to contribute to these inequalities. In this study, we evaluate the extent to which the association between race and ethnicity and all-cause mortality can be explained by differences in the exposure and vulnerability to harmful effects of different lifestyle factors.

Methods

The 1997–2014 cross-sectional, annual US National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) linked to the 2015 National Death Index was used. NHIS reported on race and ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic/Latinx), lifestyle factors (alcohol use, smoking, body mass index, physical activity), and covariates (sex, age, education, marital status, survey year). Causal mediation using an additive hazard and marginal structural approach was used.

Results

465,073 adults (18–85 years) were followed 8.9 years (SD: 5.3); 49,804 deaths were observed. Relative to White adults, Black adults experienced 21.7 (men; 95%CI: 19.9, 23.5) and 11.5 (women; 95%CI: 10.1, 12.9) additional deaths per 10,000 person-years whereas Hispanic/Latinx women experienced 9.3 (95%CI: 8.1, 10.5) fewer deaths per 10,000 person-years; no statistically significant differences were identified between White and Hispanic/Latinx men. Notably, these differences in mortality were partially explained by both differential exposure and differential vulnerability to the lifestyle factors among Black women, while different effects of individual lifestyle factors canceled each other out among Black men and Hispanic/Latinx women.

Conclusions

Lifestyle factors provide some explanation for racial and ethnic inequalities in all-cause mortality. Greater attention to structural, life course, healthcare, and other factors is needed to understand determinants of inequalities in mortality and to advance health equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Long-standing and stark racial and ethnic inequalities in health and mortality are widespread in the United States (US) [1, 2]. It is established that mortality rates among Black Americans are higher throughout most of the life course, relative to White Americans [2, 3]. In contrast, mortality rates among Hispanic/Latinx Americans are lower despite lower socioeconomic status (SES), on average, relative to White Americans [4]. In recent decades, research has focused on delineating the causes and etiology of racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality. A multitude of factors and pathways have been proposed and evaluated including societal influences (e.g., government policies) [5], environmental and occupational hazards (e.g., residential segregation) [6, 7], individual-level factors (e.g., SES, lifestyle factors, health insurance, and access to quality health care) [1, 2, 8,9,10], genetic factors [11], and potential biases in study designs, such as those related to selective migration (e.g., the salmon bias) [12, 13]. However, the complex and interrelated relationships and pathways in which these variables affect health and mortality have not been systematically evaluated and a large proportion of the observed racial and ethnic inequalities remains unexplained.

Lifestyle factors (such as smoking, alcohol use, physical inactivity, and obesity) are an important driver of inequalities in health, explaining, for example, more than two thirds of the association between SES and all-cause mortality [14, 15]. Although some evidence suggests that lifestyle factors are important in explaining racial and ethnic disparities [2, 3, 16, 17], no studies have used a comprehensive approach that evaluates multiple lifestyle factors together and their mediating and/or moderating effects. Evaluating multiple lifestyle factors is important as lifestyle factors may cluster together in distinct ways that vary by race and ethnicity [18, 19]. Understanding the mediating or moderating effects is essential in delineating potential mechanisms such as differential exposure, whereby health-promoting or unhealthy lifestyle factors are unevenly distributed across racial and ethnic groups (a mediation hypothesis), and differential vulnerability, whereby the same lifestyle factor can be more deleterious to specific racial and ethnic groups (a moderation hypothesis). Disentangling these two mechanisms is important given that unique policy implications can arise from them [20, 21].

Overall, the extent and means by which lifestyle factors might explain racial and ethnic disparities is largely unknown. Using a comprehensive model (Fig. 1) and a large cohort from the US, the current study aims to delineate the extent to which racial and ethnic differences in all-cause mortality can be explained by (i) differential exposure to lifestyle factors, and (ii) differential vulnerability to the harmful effects of each lifestyle factors across different race and ethnicity groups. The lifestyle factors considered were smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, and body mass index (BMI).

Methods

Participants

Data came from the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) linked to the National Death Index (NDI) using probabilistic record matching [22]. NHIS is an annual, nationally representative, cross-sectional household survey of the civilian non-institutionalized US population (i.e., active duty members of the US military and individuals living in an institution such as residential care facilities or prisons were not sampled). NHIS utilized a complex, multistage sample design that involved stratification, clustering, and oversampling of specific population subgroups. Every year approximately 35,000 households are enrolled, from which one adult is randomly selected for a face-to-face interview. An annual assessment of all lifestyle factors in sufficient detail started in 1997, and NHIS data up to 2014 have been linked to the NDI. Therefore, this study included pooled NHIS data from 1997 to 2014. The NDI contains information on vital status, time of death, and time last presumed alive with follow-up to December 31, 2015. Our sample was comprised of the adults (ages ≥ 18 years) who were not missing data on the exposure, mediators, outcome, and covariates; those with complete and missing data were largely similar across a range of characteristics (Supplementary Table S1). Participants over 85 years of age at the time of NHIS administration were removed given that their exact age was not available through the public use data files.

Measures

The outcome was time to all-cause mortality, operationalized as the time from the NHIS survey to death or last presumed alive. Race and ethnicity, the independent variable of interest, was self-reported and categorized as non-Hispanic White (reference category; henceforth White), non-Hispanic Black/African American (henceforth Black), and Hispanic/Latinx. We further distinguished all other non-Hispanic racial and ethnic groups (hereafter, non-Hispanic Other) for descriptive analyses, though sample size was too small for inclusion in the main analyses.

Participants’ report of the frequency and quantity of alcoholic beverage consumed in the past 12 months was converted to grams of pure alcohol consumed per day, assuming 14 g of pure alcohol per drink. Alcohol use was categorized according to the standards of the World Health Organization [23] and included: (1) never drinkers (no drinks in the past year and less than 12 drinks in any one year or entire life), (2) former drinkers (no drinks in the past year but have had at least 12 drinks in any one year), (3) category I (men: (0, 40] grams per day; women: (0, 20] grams per day; reference category), (4) category II (men: (40, 60] grams per day; women: (20,40] grams per day), (5) category III (men: >60 g per day; women: >40 g per day). With respect to smoking, participants were asked to report whether they (1) have smoked at least 100 cigarettes over their entire life, and (2) whether they currently smoked cigarettes. Smoking cigarettes was categorized as never smokers (reference category), former smokers, current someday smokers, and current everyday smokers. Based on self-reported height and weight, BMI was calculated and categorized according to current WHO guidelines as underweight (< 18.5 kg/m2), normal weight (18.5-24.99 kg/m2; reference category), pre-obesity (25-29.99 kg/m2) or obese (≥ 30 kg/m2) [24]. With respect to physical activity, participants reported how often and for how long they performed vigorous and light-moderate leisure-time physical activities of at least 10 min. No timeframe (e.g., over the past year, or past month) was specified. The length of moderate physical activity per week was calculated, assuming that 1 min of vigorous physical activity is equivalent to 2 min of moderate physical activity [25]. Physical activity was categorized as sedentary (0 min/week), somewhat active (< 150 min) or active (≥ 150 min; reference category), given the WHO recommendations of 150–300 min of moderate-intensity physical activity per week [26].

The covariates used in all models were age (continuous), sex, educational attainment, marital status, and survey year (continuous). Educational attainment was categorized as low (high school diploma or less), medium (some college but no bachelor’s degree), or high (bachelor’s degree or more), and was treated as a proxy for socioeconomic status; given its ubiquity in the extant literature, stability over time, and completeness of data (e.g., relative to income) in the NHIS. Marital status was a binary variable indicating whether the individual was married or living with partner.

Statistical analyses

Causal mediation analysis using the marginal structural approach with Aalen’s additive hazard models was used, as described by Lange et al. [27,28,29]. Briefly, this flexible approach uses a counterfactual framework and allows for the direct parameterization of natural ‘direct’ and ‘indirect’ effects through multiple mediators and exposure-mediator interactions. The total effect of race and ethnicity on mortality was decomposed into three components (Fig. 1): (1) the average pure indirect effect through each mediator (indicating differential exposure), (2) the average indirect effect of the mediated interaction between race and ethnicity and each mediator (indicating differential vulnerability), and (3) the average ‘direct’ effect of race and ethnicity independent of mediators and covariates. The model simultaneously included all mediators (lifestyle factors: alcohol use, smoking, BMI, physical activity) and covariates (age, educational attainment, marital status, and survey year), and we fit separate models for men and women. Aalen’s additive hazard models have the advantage of directly estimating additive interactions (reflecting differential vulnerability), which are of greater importance (relative to multiplicative interactions) for public health [30].

All analyses were completed in R 4.1.3, using the timereg package (version 2.0.2) [31]; the statistical code is publicly available (see below). The timereg package does not allow for complex sampling designs and survey weights were not utilized given the analytical and computational complexity of the analyses.

In a sensitivity analysis, causal mediation models were repeated without education included as a covariate, recognizing that race and ethnicity are deeply tied to SES in the US [32], and prior research shows SES differences in effects of lifestyle factors on mortality [14, 15].

Results

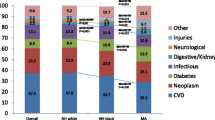

Participants were 465,073 adults (55% women, mean age 46.4 years [SD 17.3]), of whom 63% were non-Hispanic White, 15% non-Hispanic Black, 17% Hispanic/Latinx, and 5% non-Hispanic Other (of whom 12% were American Indian/American Natives, and 53% Asian and Pacific Islander Americans; see Table 1 for unweighted and Supplementary Table S2 for weighted data). Participants were followed an average of 8.9 years (SD 5.3) during which 24,296 and 25,508 deaths in men and women, respectively, were observed. At the time of survey completion, 22% of the men had never drunk alcohol, 50% had never smoked, 31% had a healthy weight, and 49% were physically active. In women, 39% had never drunk alcohol, 62% had never smoked, 42% had a healthy weight, and 40% were physically active. Relative to White adults, the prevalence of category II and III alcohol use and everyday smoking were lower among Black, Hispanic/Latinx, and non-Hispanic Other men and women (Fig. 2 for unweighted and Supplementary Figure S1 for weighted data). The opposite pattern was observed for obesity and sedentary physical activity, with a higher prevalence among Black and Hispanic/Latinx compared to White adults. Figure 3 presents the overall survival probability as a function of age, with the median survival probability being markedly lower in Black women (81 years, 95% confidence intervals [CI]: 80.5, 81.5) and men (74.8 years, 95%CI: 74.0, 75.5) than for other racial and ethnic groups (women: 84.5–86.5 years, men: 78.2–81.8 years).

Table 2 presents the results of the causal mediation analyses, controlling for all covariates and lifestyle factors. Relative to White adults, Black adults experienced 21.7 (men; 95%CI 19.9, 23.5) and 11.5 (women; 95%CI 10.1, 12.9) additional deaths per 10,000 person-years, whereas Hispanic/Latinx women experienced 9.3 (95%CI 8.1, 10.5) fewer deaths per 10,000 person-years after adjusting for covariates. Mortality was similar among White and Hispanic/Latinx men, after adjusting for covariates.

Table 2 further presents the effects of differential exposure and vulnerability to each lifestyle factor. The strongest effects were observed for smoking, finding that lower exposure to smoking resulted in 5.9 to 17.0 fewer deaths per 10,000 person years in Black and Hispanic/Latinx adults, relative to White adults (depending on the subgroup). However, Black men and Hispanic/Latinx adults were also more vulnerable to the adverse effects of smoking, which resulted in 2.2 to 11.7 additional deaths per 10,000 person years. The opposite pattern was observed for physical activity, finding that greater exposure to a sedentary lifestyle was associated with 4.6 to 7.8 additional deaths per 10,000 person years among Black and Hispanic/Latinx adults, relative to White adults, and that Black women and Hispanic/Latinx adults were less vulnerable to the adverse effects of physical inactivity, resulting in 1.7 to 5.0 fewer deaths per 10,000 person years. With respect to alcohol use, Hispanic/Latinx men were similar to White men. Among Black adults and Hispanic/Latinx women, exposure to alcohol use was associated with 1.4 to 5.1 additional deaths per 10,000 person-years, relative to White men and women. But this effect was partially offset by a greater resilience (differential vulnerability) to the adverse effects of alcohol use in these groups. Lastly, with respect to BMI, differential exposure and vulnerability effects were relatively small and offset each other.

Notably, the net indirect effect through lifestyle factors was not significant among Black men and Hispanic/Latinx women, and did not contribute overall to racial and ethnic inequalities in these racial and ethnic groups; different levels of physical activity were associated with additional deaths, whereas a lower prevalence of smoking was associated with fewer deaths. The results of the sensitivity analysis excluding education as covariate were consistent with our main analysis and did not change our conclusions (Supplementary Table S3). However, it is noteworthy that the total effect of race and ethnicity on mortality, as well as the net indirect effect were larger when not adjusting for education in our models.

Discussion

The current study sought to evaluate the mechanism and extent to which lifestyle factors contribute to racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality among US adults. Specifically, we examined whether these inequalities can be explained by indirect effects through differential exposure and differential vulnerability to harmful effects of different lifestyle factors.

First, and consistent with the extant literature [2,3,4], we found that relative to White adults, mortality rates were higher for Black men and women, and lower for Hispanic/Latinx women. Our key finding and the novel contribution of this study was that mechanisms of differential exposure and vulnerability to lifestyle factors help to explain the disparity in mortality rates between White and Black women, and the equivalent mortality rates of White and Hispanic/Latinx men. This was, however, not the case for Black men and Hispanic/Latinx women. In other words, lifestyle factors cannot explain the observed racial and ethnic inequalities in all-cause mortality in the latter groups. This is because the net indirect effect of race and ethnicity through differential exposure and vulnerability to lifestyle factors did not contribute to the observed inequalities among Black men and Hispanic/Latinx women given individual indirect effects canceled each other out. Specifically, additional deaths among Black men and Hispanic/Latinx women were attributed to a higher exposure to sedentary physical activity, while a lower prevalence of smoking resulted in fewer deaths, relative to White men and women. This finding that particularly highlights the differential exposure to different lifestyle factors across racial and ethnic groups is consistent with past studies [3, 16, 33, 34]. As for differential vulnerability, the observed effects were small overall and might be linked to unmeasured mortality risk factors associated with different lifestyle factors. For example, prior research has found that White alcohol users are at increased risk for alcohol-impaired driving [35] and for continuing to drink heavily following a diagnosis of a serious health condition compared to other racial and ethnic groups [36]. Such factors could result in White men and women being more vulnerable to the detrimental health effects of alcohol, as observed in our findings. The results of the current study help to advance the extant literature through our use of a comprehensive model to decompose the effects of differential exposure and vulnerability. Our results suggest that public health interventions targeting physical inactivity among Black and Hispanic/Latinx adults are important. However, targeting lifestyle factors alone, without consideration of more fundamental forces, such as poverty, structural racism, and limited opportunity [37], will not likely improve racial and ethnic disparities in mortality observed for Black men and women.

Our findings for the somewhat limited role of lifestyle factors in explaining racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality stand in contrast to research on socioeconomic disparities in mortality, which report that the latter inequalities are largely attributed to the net indirect effect of lifestyle factors [14, 15]. This difference in findings may be because lifestyle factors putting individuals at higher health risks were found to cluster among low SES groups [14, 15], in contrast to our finding of a lower prevalence of smoking among Black and Hispanic/Latinx adults which resulted in a relative protective effect. Taken together, these findings have important public health implications in highlighting that socioeconomic and racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality in the US may arise in unique ways (e.g., racial residential segregation is likely more relevant to the Black-White mortality gap) and likely require distinctive intervention approaches. Even so, past studies have shown that SES is an important mediator of racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality [3, 16, 38], and reducing socioeconomic inequalities in mortality potentially by targeting the root causes of socioeconomic health inequalities may in turn also reduce racial and ethnic disparities. The role of SES in racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality was further stressed in our sensitivity analysis, in which we have repeated the causal mediation models without adjusting for education, resulting in a higher total and net indirect effect of race and ethnicity on all-cause mortality in Black and Hispanic/Latinx adults. Lower racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality when adjusting for education appear plausible, as education is an important predictor of disease onset and progression, and racial and ethnic disparities in education exist [39]. This finding further suggests an intersectional dimension of both factors.

In interpreting the results presented above, limitations should be considered. First, the choice of covariates is important given that causal mediation models assume no unmeasured confounders for the exposure-outcome, exposure-mediator, and mediator-outcome relationships, and no mediator-outcome confounders caused by the exposure. Mediators are also assumed to have no causal effect on each other. Residual confounding by unmeasured risk factors in our analyses is possible. In particular, chronic health conditions and diet quality were not taken into account and might vary across racial and ethnic groups. Second, because the data arose from participants’ self-report from a single time point, reporting bias and changes in lifestyle factors over time may have introduced misclassification and underestimated the association between lifestyle factors and mortality. Third, the exclusion of the institutionalized population in the NHIS may have led to an underestimation of racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality, as well as the indirect effects of lifestyle factors, as racial and ethnic minorities are likely to be overrepresented in some of these populations [40]. Moreover, lifestyle factors linked to increased mortality risks, such as category II and III alcohol use, are expected to be higher in the institutionalized than in the non-institutionalized population [41]. Fourth, we were unable to account for migration dynamics, which may have impacted on survival probabilities, as movements vary across racial and ethnic groups. However, it needs to be acknowledged that the US has a positive net migration rate [42] and prior research on the impact of migration on lower mortality among Hispanics residing in the US concluded that out-migration appears to have only little impact on their mortality advantages [13]. Lastly, given the analytical and computational complexity of the analyses we could not account for the complex survey design of the NHIS, which may have affected estimates of the indirect effects through differential exposure in particular. However, comparing the prevalence of lifestyle factors in the weighted (Table 1) and unweighted data (Supplementary Table S2), only minor differences are observed, suggesting that not accounting for the complex survey design is unlikely to have substantially influenced our results concerning differential exposure to lifestyle factors. Given this analytical and computational complexity and due to sample size considerations, our analyses also did not separate US- and foreign-born Hispanic/Latinx adults, which is an important differentiator given that foreign born status and acclimatization in the US are important factors contributing to Hispanic/Latinx’s mortality [2, 12]. Similarly, a more detailed disaggregation and analysis of the non-Hispanic Other group was not possible.

Overall, our study of multiple lifestyle factors demonstrates that their net effect helps to explain some portion of the observed racial and ethnic inequalities in all-cause mortality. While differential exposure and vulnerability to multiple lifestyle factors contributed to the disparity in Black women’s all-cause mortality, in other groups, indirect effects of individual lifestyle factors canceled each other out. Importantly, lifestyle factors do not develop in isolation but are a product of more fundamental forces associated with structural and social determinants of health [37]. Future work should endeavour to understand the differential exposure and vulnerability effects of other factors potentially underlying racial and ethnic inequalities in mortality, including societal factors, environmental and occupational hazards, and other individual-level factors not necessarily related to lifestyle such as exposure to stress and resilience.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available from National Center for Health Statistics; the dataset was derived from sources in the public domain: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/1997-2018.htm and https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data-linkage/mortality-public.htm. The statistical code is available at https://github.com/yachenz1/SIMAH_Ethnicity_x_Lifestyle.

References

Williams DR, Collins C. US socioeconomic and racial differences in Health: patterns and explanations. Ann Rev Sociol. 1995;21:349–86.

Sudano JJ, Baker DW. Explaining US racial/ethnic disparities in health declines and mortality in late middle age: the roles of socioeconomic status, health behaviors, and health insurance. Soc Sci Med. 2006 Feb;62(4):909–22.

Beydoun MA, Beydoun HA, Mode N, Dore GA, Canas JA, Eid SM, Zonderman AB. Racial disparities in adult all-cause and cause-specific mortality among us adults: mediating and moderating factors. BMC Public Health. 2016 Dec;16(1):1113.

Ruiz JM, Steffen P, Smith TB. Hispanic Mortality Paradox: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of the longitudinal literature. Am J Public Health. 2013 Mar;103(3):e52–60.

Williams DR, Collins C. Racial residential segregation: a fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Rep. 2001 Sep;116(5):404–16.

LaVeist T, Pollack K, Thorpe R, Fesahazion R, Gaskin D, Place. Not race: disparities dissipate in Southwest Baltimore when Blacks and Whites live under similar conditions. Health Aff. 2011 Oct;30(10):1880–7.

Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health: Neighborhoods and health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010 Feb;1186(1):125–45.

Lillie-Blanton M, Hoffman C. The role of Health Insurance Coverage in reducing Racial/Ethnic disparities in Health Care. Health Aff. 2005 Mar;24(2):398–408.

Institute for Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care (with CD) [Internet]. Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press. 2003 [cited 2023 May 9]. Available from: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/12875.

Fiscella K, Sanders MR. Racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of Health Care. Annu Rev Public Health 2016 Mar 18;37(1):375–94.

Sankar P. Genetic Research and Health Disparities. JAMA. 2004 Jun;23(24):2985.

Fenelon A. Rethinking the Hispanic Paradox: the Mortality experience of mexican immigrants in traditional gateways and new destinations. Int Migrat Rev. 2017 Sep;51(3):567–99.

Turra CM, Elo IT. The impact of Salmon Bias on the hispanic mortality advantage: New evidence from Social Security Data. Popul Res Policy Rev 2008 Oct;27(5):515–30.

Puka K, Buckley C, Mulia N, Lasserre AM, Rehm J, Probst C. Educational Attainment and Lifestyle Risk factors Associated with all-cause mortality in the US. JAMA Health Forum 2022 Apr 8;3(4):e220401.

Nandi A, Glymour MM, Subramanian SV. Association Among Socioeconomic Status, Health Behaviors, and All-Cause Mortality in the United States: Epidemiology. 2014 Mar;25(2):170–7.

Krueger PM, Saint Onge JM, Chang VW. Race/ethnic differences in adult mortality: the role of perceived stress and health behaviors. Soc Sci Med. 2011 Nov;73(9):1312–22.

Thorpe RJ, Koster A, Bosma H, Harris TB, Simonsick EM, Van Eijk JThM, Kempen GIJM, Newman AB, Satterfield S, Rubin SM, Kritchevsky SB. Racial differences in mortality in older adults: factors beyond socioeconomic status. Ann behav med. 2012 Feb;43(1):29–38.

Meader N, King K, Moe-Byrne T, Wright K, Graham H, Petticrew M, Power C, White M, Sowden AJ. A systematic review on the clustering and co-occurrence of multiple risk behaviours. BMC Public Health. 2016 Dec;16(1):657.

Cook WK, Kerr WC, Karriker-Jaffe KJ, Li L, Lui CK, Greenfield TK. Racial/Ethnic variations in clustered risk behaviors in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2020 Jan;58(1):e21–9.

Diderichsen F, Hallqvist J, Whitehead M. Differential vulnerability and susceptibility: how to make use of recent development in our understanding of mediation and interaction to tackle health inequalities. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2019 Feb 1;48(1):268–74.

Blas E, Kurup AS, World Health Organization, editors. Equity, social determinants, and public health programmes. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. p. 291.

National Center for Health Statistics. Office of Analysis and Epidemiology. The linkage of National Center for Health Statistics Survey Data to the National Death index – 2015 linked mortality file (LMF): methodology overview and analytic considerations. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2019.

World Health Organization. International Guide for Monitoring Alcohol Consumption and related harm. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2001.

World Health Organization. A healthy lifestyle - WHO recommendations [Internet]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2010. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/a-healthy-lifestyle---who-recommendations.

U.S. Department of Health Human Services. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans (2nd edition). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health Human Services; 2018.

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S, Borodulin K, Buman MP, Cardon G, Carty C, Chaput JP, Chastin S, Chou R, Dempsey PC, DiPietro L, Ekelund U, Firth J, Friedenreich CM, Garcia L, Gichu M, Jago R, Katzmarzyk PT, Lambert E, Leitzmann M, Milton K, Ortega FB, Ranasinghe C, Stamatakis E, Tiedemann A, Troiano RP, Van Der Ploeg HP, Wari V, Willumsen JF. World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med. 2020 Dec;54(24):1451–62.

Lange T, Rasmussen M, Thygesen LC. Assessing Natural Direct and Indirect Effects through multiple pathways. Am J Epidemiol 2014 Feb 15;179(4):513–8.

Lange T, Vansteelandt S, Bekaert M. A Simple Unified Approach for Estimating Natural Direct and Indirect Effects. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2012 Aug 1;176(3):190–5.

Lange T, Hansen JV. Direct and Indirect Effects in a Survival Context. Epidemiology. 2011 Jul;22(4):575–81.

Rod NH, Lange T, Andersen I, Marott JL, Diderichsen F. Additive Interaction in Survival Analysis: Use of the additive hazards model. Epidemiology. 2012 Sep;23(5):733–7.

Scheike TH, Martinussen T. Dynamic regression models for survival data. New York, NY: Springer; 2006.

Williams DR, Race. Socioeconomic status, and Health the added Effects of racism and discrimination. Volume 896. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences; 1999 Dec. pp. 173–88. 1.

Jackson CL, Hu FB, Kawachi I, Williams DR, Mukamal KJ, Rimm EB. Black–white differences in the Relationship between Alcohol drinking patterns and mortality among US Men and Women. Am J Public Health. 2015 Jul;105(S3):534–43.

Caetano R, Vaeth PAC, Chartier KG, Mills BA. Chapter 37 - epidemiology of drinking, alcohol use disorders, and related problems in US ethnic minority groups. In: Sullivan EV, Pfefferbaum A, editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. Elsevier; 2014. pp. 629–48.

U.S. Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. Alcohol and Highway Safety: Special Report on Race/Ethnicity and Impaired Driving [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2023 May 23]. Available from: http://doi.apa.org/get-pe-doi.cfm?doi=10.1037/e728722011-001.

Cherpitel CJ, Ye Y, Kerr WC. Association of short-term changes in drinking after onset of a serious health condition and long-term heavy drinking. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022 Dec;241:109691.

Short SE, Mollborn S. Social determinants and health behaviors: conceptual frames and empirical advances. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015 Oct;5:78–84.

Blakely T, Disney G, Valeri L, Atkinson J, Teng A, Wilson N, Gurrin L. Socioeconomic and Tobacco Mediation of ethnic inequalities in mortality over time: repeated Census-mortality Cohort Studies, 1981 to 2011. Epidemiology. 2018 Jul;29(4):506–16.

Herd P, Goesling B, House JS. Socioeconomic position and health: the Differential Effects of Education versus Income on the onset versus progression of health problems. J Health Soc Behav. 2007 Sep;48(3):223–38.

Bui J, Wendt M, Bakos A. Understanding and addressing Health Disparities and Health needs of Justice-Involved populations. Public Health Rep. 2019 May;134(1suppl):3S–7S.

Shield KD, Rehm J. Difficulties with telephone-based surveys on alcohol consumption in high-income countries: the canadian example: difficulties with telephone-based surveys on alcohol consumption. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2012;21(1):17–28.

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World Population Prospects: The 2022 Revision: Crute rate of net migration in the US [Internet]. United Nations; 2023 [cited 2023 May 23]. Available from: https://population.un.org/dataportal/data/indicators/66,65/locations/840/start/1990/end/2023/line/linetimeplot.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health, awarded to CP (Award Number R01AA028009). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KP and CP conceptualized the study. KP curated the data and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KP and YZ conducted the statistical analyses and CK was responsible for the revision of the original manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and to the writing and revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval

All adult participants in the NHIS provided written informed consent. NHIS is approved by the Research Ethics Review Board of the National Center for Health Statistics and the U.S. Office of Management and Budget.

Consent for publication

not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Puka, K., Kilian, C., Zhu, Y. et al. Can lifestyle factors explain racial and ethnic inequalities in all-cause mortality among US adults?. BMC Public Health 23, 1591 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16178-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16178-6