Abstract

Background

Whether past disaster experiences affect the association between changes in social isolation and depressive symptoms is largely unknown. This study examined the association between changes in social isolation and depressive symptoms among survivors who experienced earthquake damage in the aftermath of the Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE).

Methods

We analyzed longitudinal data from 10,314 participants who responded to self-report questionnaires on the Lubben Social Network Scale-6 (LSNS-6) and the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depressive Scale (CES-D) in both the baseline survey (FY2013 to FY2015) and follow-up survey (FY2017 to FY2019) after the GEJE. According to changes in the presence of social isolation (< 12 of LSNS-6) at two time points, participants were categorized into four groups: “not socially isolated,” “improved socially isolated,” “newly socially isolated,” and “continuously socially isolated.” At the follow-up survey, a CES-D score of ≥ 16 indicates the presence of depressive symptoms. The adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using the logistic regression analysis to examine the influence of the change in social isolation over four years on depressive symptoms.

Results

Participants who were newly socially isolated had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who were not socially isolated (AOR = 1.89, 95% CI = 1.61 − 2.23). In addition, AORs were highest for those who were continuously socially isolated and had experienced house damage (AOR = 2.17, 95% CI = 1.73 − 2.72) and those who were newly socially isolated and had not experienced the death of family members due to the GEJE (AOR = 1.88, 95%CI = 1.60 − 2.22).

Conclusion

Our longitudinal findings suggest that being newly or continuously socially isolated is associated with a risk of depressive symptoms, not only among those who had experienced house damage or the death of a family member, but also those who had not, in the disaster-affected area. Our study underlines the clinical importance of social isolation after a large-scale natural disaster and draws attention to the need for appropriate prevention measures.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Natural disasters, such as large-scale earthquakes, can completely change the living environment and profoundly impact people’s minds and bodies [1, 2]. In the Great East Japan Earthquake (GEJE) of 2011, the massive earthquake and tsunami caused significant physical and personal damage, and those who were spared had to make drastic adjustments to their living conditions [3]. Moreover, due to the drastic changes in the living environment, social isolation occurred in the affected areas, and those who were socially isolated experienced deteriorating mental health [4,5,6].

Social isolation can negatively influence psychological health, leading to depressive symptoms [7, 8]. Oxman et al. reported that social isolation is among the most potent predictors of depressive symptoms among the elderly through data obtained from a probability sample of 2,806 individuals over the age of 65 living in the U.S. in Connecticut [9]. Santini et al. also found that social isolation predicted higher depressive symptoms in data from 3,005 adults aged 57–85 from the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) [10].

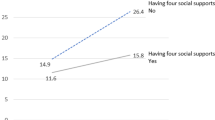

Only a few studies have examined longitudinal changes in social isolation after an earthquake [5, 11]. For instance, Sone et al. analyzed changes in social isolation between 2011 and 2014 using longitudinal data from 959 participants in a community-based survey in Miyagi Prefecture. They found that 11.1% of participants were “socially isolated,” 10.0% were “not socially isolated,” and 14.9% remained “socially isolated” [5]. In addition, among the participants who had psychological distress at the baseline, the rate of improvement of psychological distress was significantly higher in participants who “remained not socially isolated” [5]. Four to six years after the GEJE, Sekiguchi et al. used propensity score analysis to examine changes in social isolation based on whether or not people moved into publicly reconstructed housing. They reported a significant rise in the prevalence of social isolation among those who moved into newly constructed housing [11]. Meanwhile, longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms after the earthquake have been examined in several studies, but the findings are inconsistent [12,13,14]. For instance, Goenjian et al. reported that depression scale scores improved significantly over time based on data collected 1.5 and 4.5 years post-trauma from 29 individuals who had suffered mild earthquake trauma in the 1988 Spitak earthquake [12]. Kino et al. examined long-term trends in mental health disorders after the GEJE using data from 1,735 community residents of Iwanuma City, Miyagi Prefecture, and reported that the prevalence of depressive symptoms remained stable at approximately 29% in both 2013 and 2016 [13]. Meanwhile, Hikichi et al. reported that the mean scores of depressive symptoms increased slightly over time for 2.5 years and 5.5 years after the earthquake based on data from 2,664 community residents in Iwanuma City, Miyagi Prefecture, after the GEJE [14]. However, how disaster situations such as house damage and the death of family members affect the association between subsequent social isolation and depressive symptoms is largely unclear.

Thus, we aimed to examine the longitudinal change association between social isolation and depressive symptoms due to the experience of earthquake damage in the aftermath of the GEJE.

Methods

Study population

This study is part of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Community-Based Cohort Study (TMM CommCohort Study) [15, 16]. The baseline survey was conducted between 2013 and 2016 in Miyagi and Iwate Prefectures in Japan. This study employed data from individuals living in 20 municipalities, including 12 municipalities bordering the coast of Iwate Prefecture and eight surrounding areas in Iwate Prefecture. Study participants were recruited at municipal specific health check-up sites and at our facility. Recruitment was done by calling for participation in the cohort study at municipal specific health check-up sites in selected municipalities or using mass media such as newspapers and flyers to recruit participants [15, 16]. The inclusion criteria were persons aged 20 years or older who were registered in the basic resident register of all municipalities in Iwate Prefecture at the time of enrollment. This manuscript adheres to the STROBE guidelines (see Supplementary Table 1).

We followed 32,320 of the 32,919 participants in the baseline surveys, excluding six dual enrollees and 593 individuals who withdrew consent. Among these, 20,810 individuals participated in the second survey (FY2017 to FY2019). Of these participants, we excluded 210 participants who did not return the questionnaire, 1,500 with missing data on the Lubben Social Network Scale (LSNS-6), 971 with missing data on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression Scale (CES-D), and 1,424 with missing data in the covariate variables. We also referred to the study by Marx et al. [17] and excluded 6,381 participants who have co-morbid disease (anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, migraine, cerebrovascular disease, hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia), which was picked up in the medical history section of our questionnaire. Consequently, we analyzed 10,314 participants (3,144 men and 7,170 women; mean age at baseline survey 57.0 ± 11.8 years).

Measurements

Depressive symptoms in baseline and second survey

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the CES-D [18]. The reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the CES-D were confirmed [19]. Depressive symptoms were defined as a CES-D score of ≥ 16 [18, 19].

Social isolation in baseline and second survey

Social isolation was assessed using the LSNS-6 [20, 21]. The LSNS-6 contains six items on social connections (three questions about family ties and three questions about friendship ties). On a 6-point Likert scale, each item is ranked. The LSNS-6 scores range from 0 to 30. The reliability and validity of the LSNS-6’s Japanese version have been confirmed [22]. A score of < 12 [21, 22] indicates social isolation.

House damage and death of family members due to the GEJE in baseline survey

We used six options to assess house damage caused by the GEJE: (1) totally damaged (including all outflows), (2) seriously damaged, (3) half-damaged, (4) partially damaged, (5) no damage, and (6) non-residence. These options were further classified as damaged (totally damaged, seriously damaged, half-damaged, and partially damaged) or undamaged (no damage or non-residence). Participants responded affirmatively or negatively to questions regarding the death of family members due to the GEJE.

Covariates

The following demographic characteristics were used as covariates in the analysis. These factors are linked to depressive symptoms and social isolation [23,24,25]: age (continuous), sex, education level (junior high school, high school, college or university or higher, and other), marital status (unmarried or married), number of household members (living alone or ≥ 2), work status (unemployed or employed), smoking habits (nonsmoker or current smoker), drinking habits (nondrinker or current drinker), body mass index (BMI, < 18.5, 18.5 to < 25, or ≥ 25 kg/m2), and insomnia. Insomnia was defined as a score of ≥ 6 on the Athens Insomnia Scale [26, 27]. The educational level was asked only in the baseline survey. Other variables used were the values answered during the second survey.

Statistical analysis

First, McNemar’s test was used to compare the prevalence of depressive symptoms and social isolation in the baseline and second surveys. The participants were categorized into four groups based on their social isolation level (low: LSNS-6 < 12) in the baseline and second survey: (1) not socially isolated (low and low), (2) improved socially isolated (high and low), (3) newly socially isolated (low and high), and (4) continuously socially isolated (high and high). Second, we used the analysis of variance for continuous variables and the chi-square test for categorical variables to compare the characteristics of the four groups. Third, the association between social isolation and depressive symptoms was examined. We used logistic regression analysis to estimate the multivariate adjusted odds ratios (AORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after adjusting for covariates to indicate whether the change in social isolation was associated with depressive symptoms after four years. We also conducted stratified analyses by sex and age group (< 65 or ≥ 65 years) and by risks of the baseline depressive symptoms (higher or lower risk).

We hypothesized that the experience of damage from disasters, such as the house damage or the death of family members due to the GEJE, might be a potential risk for social isolation, which might influence depressive symptoms. To investigate how the disaster situation influences the relationship between social isolation and depressive symptoms, we also stratified house damage and the death of family members. In addition, to examine whether social isolation has different effects on depressive symptoms depending on the presence or absence of experiences such as house damage or the death of family members due to the GEJE, the main effect and interaction terms were simultaneously fed into the model. To examine the interaction between house damage (or death of family members due to the GEJE) and social isolation, the product term of house damage (or death of family members due to the GEJE) and social isolation was put into a model that was not stratified by house damage (or death of family members due to the GEJE). The results shows p values for the product term of house damage (or death of family members due to the GEJE) and social isolation.

Moreover, to avoid the possibility of reverse causalities, we performed the same analysis, excluding 2,730 participants who have depressive symptoms in the baseline survey.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25.0 for Windows (IBM, Tokyo, Japan). P values of < 0.05 indicated statistical significance.

Results

Table 1 presents the distribution of the changes in depressive symptoms. The prevalence of depressive symptoms did not differ significantly between the baseline and second surveys (26.5% and 25.7%, p = 0.10). Regarding the change in the prevalence of depressive symptoms during the same period, 10.7% of the participants showed an improvement, 9.9% showed deterioration, and 15.8% remained high in depressive symptoms. Meanwhile, Table 2 presents the distribution of changes in the prevalence of social isolation. The prevalence of social isolation differed significantly between the baseline and second survey (27.6% and 31.0%, p < 0.001).

Table 3 displays baseline characteristics according to changes in social isolation. Compared to other participants, those who are continuously socially isolated were more likely to be younger, men, unmarried, living alone, exhibiting depressive symptoms, and suffering from insomnia. In addition, newly socially isolated participants were more likely to be highly educated, current smokers, current drinkers, and thin compared with other participants.

The AORs (95% CI) for depressive symptoms according to changes in social isolation are shown in Table 4. Participants who are newly and continuously socially isolated had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who are not socially isolated. This tendency did not change in the stratified analysis by sex, age group, and risks of the baseline depressive symptoms (Supplementary Tables 2, 3, and 4).

Table 5 shows that participants who are newly and continuously socially isolated who had experienced house damage had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who not socially isolated [newly socially isolated: AOR (95% CI) = 1.92 (1.47–2.52); continuously socially isolated: AOR (95% CI) = 2.17 (1.73–2.72)]. In addition, participants who are newly socially isolated and those who continuously socially isolated who did not experienced house damage had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who are not socially isolated [newly socially isolated: AOR (95% CI) = 1.88 (1.53–2.30); continuously social isolated: AOR (95% CI) = 1.73 (1.45–2.30)]. There was no interaction between house damage and social isolation (p = 0.285).

Table 6 demonstrates that participants who fall into the improved socially isolated, newly socially isolated, and continuously socially isolated who had not the death of family members due to GEJE had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who no socially isolated [AOR (95% CI) = 1.23 (1.01 − 1.50), 1.88 (1.60 − 2.22), and 1.88 (1.63 − 2.16), respectively]. Participants who are improved socially isolated who had the death of family members due to the GEJE also had a significantly lower prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who are not socially isolated [AOR (95% CI) = 0.37 (0.14 − 0.97)]. There was no interaction between the death of family members due to the GEJE and social isolation (p = 0.079).

Moreover, we performed the same analysis, excluding 2,730 participants who had depressive symptoms in the baseline survey. Participants who are newly and continuously socially isolated had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who are not socially isolated after adjusting for all the covariates (Supplementary Table 5). The AORs (95% CI) for depressive symptoms according to social isolation change stratified by sex are shown in Supplementary Table 6. There was no interaction between age group and social isolation (p = 0.322). The AORs (95% CI) for depressive symptoms according to social isolation change stratified by age group are shown in Supplementary Table 7. There was no interaction between age group and social isolation (p = 0.346). The AORs (95% CIs) for depressive symptoms according to house damage and social isolation change are shown in Supplementary Table 8. Participants who are newly and continuously socially isolated who had experienced house damage had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who are not socially isolated [newly socially isolated: AOR (95% CI) = 2.02 (1.43–2.85); continuously socially isolated: AOR (95% CI) = 2.40 (1.74–3.30)]. Furthermore, participants who are new and continuously socially isolated who did not experienced house damage had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who are not socially isolated [newly socially isolated: AOR (95% CI) = 1.99 (1.55–2.57); continuously social isolated: AOR (95% CI) = 1.75 (1.39–2.20)]. There was no interaction between house damage and social isolation (p = 0.328). The AORs (95% CIs) for depressive symptoms according to the presence or absence of death of family members caused by the GEJE and social isolation change are shown in Supplementary Table 9. Participants in the category for improved, newly, and continuously socially isolated who had not the death of family members due to GEJE had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms than those who are not socially isolated [AOR (95% CI) = 1.34 (1.01 − 1.76), 1.98 (1.61 − 2.45), and 1.93 (1.60 − 2.34), respectively]. There was no interaction between the death of family members due to the GEJE and social isolation (p = 0.580).

Discussion

This study examined the longitudinal association between social isolation and depressive symptoms after the GEJE. Although the prevalence of depressive symptoms did not differ (26.5% and 25.7%, respectively), the prevalence of social isolation differed between the baseline and second surveys (27.6% and 31.0%, respectively). Our data for social isolation showed that 11.9% of participants changed from being not socially isolated to being socially isolated, and 19.2% remained socially isolated. Using the LSNS-6, Sone et al. examined changes in the prevalence of social isolation and found that 11.1% of participants changed from being not socially isolated to being socially isolated and 14.9% remained socially isolated [5]. In terms of trends, our findings were consistent with those of the previous report and may be applicable to the progression of social isolation among survivors of other natural disasters.

We showed that the prevalence of depressive symptoms was significantly higher in participants who are newly and continuously socially isolated than in participants who are not socially isolated. Certain social settings can foster social isolation [28], and depression can be caused by social isolation [29]. The participants in our study experienced the GEJE, and it is conceivable that the disaster altered their subsequent living conditions. We consider that changes in the living environment and income may have created or sustained conditions that increased the likelihood of people isolating themselves in the aftermath of the disaster, resulting in the manifestation of depressive symptoms.

We also showed that among those who had experienced house damage, participants who are newly and continuously socially isolated had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms. Within a few years, individuals whose homes were damaged had to change their living environments, moving from shelters to temporary housing and then to disaster recovery housing [30]. As a result of repeated changes in their living environments, they may have become isolated and unable to maintain connections with others. In addition, the same tendencies were observed even among those who did not experience house damage. Individuals who did not suffer house damage may have had their previous social networks changed, triggered by the fact that there was no damage. Although others around them were affected by the damage, they may feel sorry and guilt that they were not affected and began to distance themselves from their surroundings, isolating themselves. Thus, changes in environmental factors due to earthquakes may have affected changes in social networks [5]. As a result, we consider the possibility that some people may have developed mental health problems. Depressive symptoms can be triggered by life environmental changes [31, 32].

In our study, among those who has not death of family members due to the GEJE, participants who were improved, newly, and continuously socially isolated had a significantly higher prevalence of depressive symptoms. When we examined the damage to these people’s homes, we found that they had less damage than those who were never isolated. This may be because, while those around them were grieving the loss of their immediate family members in the earthquake, they felt remorse and guilt that they had not suffered the same fate [30]. Moreover, they distanced themselves from their surroundings and became or remained socially isolated, which may have caused mental health problems and depressive symptoms. Therefore, regarding those who were socially isolated and had not experienced house damage or the death of family members due to the disaster, we believe that even if a disaster does not directly damage houses or people, the experience of a large-scale natural disaster that threatens daily life may have a latent impact on social isolation, which may become apparent over time.

We also found that those who improved from social isolation and had not experienced the death of family members due to the GEJE had a significantly higher OR for depressive symptoms. Depending on the individual, it can take years to recover from depressive symptoms [33]. While their living conditions have improved as time has passed since the disaster, and the isolated situation has improved, it is possible that the depressive symptoms may still be lingering. Meanwhile, the OR of depressive symptoms was significantly lower in those who were in the category of improved socially isolated among those who had death of family members. We believe that post-traumatic growth may have occurred. Post-traumatic growth refers to the growth of the human mind in the wake of a traumatic event that is extremely painful and distressing [34]. Experiencing the death of a family member is difficult to accept even in normal times, but it can be said that sudden separation due to an accident or disaster can often be a distressing and painful experience for those left behind to accept the fact. Post-traumatic growth is the ability to recapture the meaning of life and connections with others, be open to new possibilities, and grow as a person [34]. Even those who have been isolated for a time after the earthquake, or who have not been able to connect with others, can overcome their sadness by reevaluating the meaning of life and their relationships with others as time passes. As a result, we believe that both the state of isolation and the depressive symptoms improved.

The present study has some limitations. First, participants in this study may have had greater health awareness and better health status than the target population because they had voluntarily participated in health surveys. Therefore, the prevalence of depressive symptoms may have been underestimated, and the generalization of results must be considered carefully. Second, causality reversal, such as isolation resulting from the inability to leave the house due to illness, may exist. Finally, because we lack data prior to the GEJE, it is impossible to determine the extent to which social isolation levels prior to the GEJE impacted disaster response preparedness, which would impact depressive symptoms. Nevertheless, because our results depict a significant association, we believe that they are robust. This study is significant because few known studies have reported an association between social isolation changes and depressive symptoms after an earthquake using a population-based cohort study design and a large sample size.

Conclusion

Our longitudinal findings suggest that newly or remained social isolation is associated with the risk of depressive symptoms only among those who had experienced house damage or death of family member but also among those who had not experienced house damage or death of family member among people who lived in the disaster-affected area. It is important to understand the long-term health status of residents who have experienced a life-threatening event such as a large-scale natural disaster, even if they did not suffer damage, such as house damage or the death of a family member.

Data Availability

The TMM cohort data are available for a fee to researchers in Japan who have been approved by the prescribed registration and review procedures. For more information, visit: http://www.dist.megabank.tohoku.ac.jp/.

Abbreviations

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

- CES-D:

-

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- GEJE:

-

Great East Japan Earthquake

- LSNS-6:

-

Lubben Social Network Scale 6

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- SPSS:

-

Statistical package for social science

- TMM CommCohort Study:

-

Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Community-Based Cohort Study

References

Cianconi P, Betrò S, Janiri L. The impact of Climate Change on Mental Health: a systematic descriptive review. Front Psychiatry 2020, 11(74).

McMichael AJ, Woodruff RE, Hales S. Climate change and human health: present and future risks. The Lancet. 2006;367(9513):859–69.

Mimura N, Yasuhara K, Kawagoe S, Yokoki H, Kazama S. Damage from the Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami - A quick report. Mitig Adapt Strat Glob Change. 2011;16(7):803–18.

Kotozaki Y, Tanno K, Sakata K, Takusari E, Otsuka K, Tomita H, Sasaki R, Takanashi N, Mikami T, Hozawa A, et al. Association between the social isolation and depressive symptoms after the great East Japan earthquake: findings from the baseline survey of the TMM CommCohort study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):925.

Sone T, Nakaya N, Sugawara Y, Tomata Y, Watanabe T, Tsuji I. Longitudinal association between time-varying social isolation and psychological distress after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Soc Sci Med. 2016;152:96–101.

Tsuboya T, Aida J, Hikichi H, Subramanian SV, Kondo K, Osaka K, Kawachi I. Predictors of depressive symptoms following the Great East Japan earthquake: a prospective study. Soc Sci Med. 2016;161:47–54.

Barnett PA, Gotlib IH. Psychosocial functioning and depression: distinguishing among antecedents, concomitants, and consequences. Psychol Bull. 1988;104:97–126.

Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urb Health. 2001;78(3):458–67.

Oxman TE, Berkman LF, Kasl S, Freeman DH Jr, Barrett J. Social Support and depressive symptoms in the Elderly. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;135(4):356–68.

Santini ZI, Jose PE, York Cornwell E, Koyanagi A, Nielsen L, Hinrichsen C, Meilstrup C, Madsen KR, Koushede V. Social disconnectedness, perceived isolation, and symptoms of depression and anxiety among older Americans (NSHAP): a longitudinal mediation analysis. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(1):e62–e70.

Sekiguchi T, Hagiwara Y, Sugawara Y, Tomata Y, Tanji F, Yabe Y, Itoi E, Tsuji I. Moving from prefabricated temporary housing to public reconstruction housing and social isolation after the Great East Japan Earthquake: a longitudinal study using propensity score matching. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e026354.

Armen K, Goenjian MD, Steinberg AM,, PhD, Najarian LM,, MD, Fairbanks LA,, PhD, Tashjian M, Ph.D.and, Pynoos RS. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress, anxiety, and depressive reactions after earthquake and political violence. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(6):911–6.

Kino S, Aida J, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Long-term Trends in Mental Health Disorders after the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(8):e2013437–7.

Hikichi H, Aida J, Kondo K, Kawachi I. Six-year follow-up study of residential displacement and health outcomes following the 2011 Japan Earthquake and Tsunami. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2021;118(2):e2014226118.

Kuriyama S, Yaegashi N, Nagami F, Arai T, Kawaguchi Y, Osumi N, Sakaida M, Suzuki Y, Nakayama K, Hashizume H, et al. The Tohoku Medical Megabank Project: design and mission. J Epidemiol. 2016;26(9):493–511.

Hozawa A, Tanno K, Nakaya N, Nakamura T, Tsuchiya N, Hirata T, Narita A, Kogure M, Nochioka K, Sasaki R et al. Study profile of the Tohoku Medical Megabank Community-Based Cohort Study. J Epidemiol 2020.

Marx P, Antal P, Bolgar B, Bagdy G, Deakin B, Juhasz G. Comorbidities in the diseasome are more apparent than real: what bayesian filtering reveals about the comorbidities of depression. PLoS Comput Biol. 2017;13(6):e1005487.

Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. 1977.

Shima S, Shikano T, Kitamura T. A new self-report depression scale. Psychiatry. 1985;27:717–23.

Lubben J, Blozik E, Gillmann G, Iliffe S, von Renteln Kruse W, Beck JC, Stuck AE. Performance of an abbreviated version of the Lubben Social Network Scale among three european community-dwelling older adult populations. Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):503–13.

Lubben JE, Gironda ME. Centrality of social ties to the health and well-being of older adults, Social work and health care in an aging world. NewYork: Springer Press; 2003.

Kurimoto A, Awata S, Ohkubo T, Tsubota-Utsugi M, Asayama K, Takahashi K, Suenaga K, Satoh H, Imai Y. [Reliability and validity of the japanese version of the abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai zasshi Japanese journal of geriatrics. 2011;48(2):149–57.

Glassman AH, Helzer JE, Covey LS, Cottler LB, Stetner F, Tipp JE, Johnson J. Smoking, Smoking Cessation, and Major Depression. JAMA. 1990;264(12):1546–6.

Greenfield SF, Weiss RD, Muenz LR, Vagge LM, Kelly JF, Bello LR, Michael J. The Effect of Depression on Return to drinking: a prospective study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55(3):259–65.

Taylor HO, Taylor RJ, Nguyen AW, Chatters L. Social isolation, Depression, and psychological distress among older adults. J Aging Health. 2018;30(2):229–46.

Okajima I, Nakajima S, Kobayashi M, Inoue Y. Development and validation of the japanese version of the Athens Insomnia Scale. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67(6):420–5.

Soldatos CR, Dikeos DG, Paparrigopoulos TJ. Athens Insomnia Scale: validation of an instrument based on ICD-10 criteria. J Psychosom Res. 2000;48(6):555–60.

Klinenberg E. Social isolation, loneliness, and living alone: identifying the risks for Public Health. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(5):786–7.

Cacioppo JT, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA. Perceived social isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychol Aging. 2010;25(2):453–63.

Gagné I. Dislocation, social isolation, and the politics of recovery in Post-Disaster Japan. Transcult Psychiatry. 2020;57(5):710–23.

Allen J, Balfour R, Bell R, Marmot M. Social determinants of mental health. Int Rev psychiatry. 2014;26(4):392–407.

Brown GW, Harris TO. Life events and illness. 1989.

Eaton WW, Shao H, Nestadt G, Lee BH, Bienvenu OJ, Zandi P. Population-Based study of First Onset and Chronicity in Major Depressive Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(5):513–20.

Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J Trauma Stress. 1996;9(3):455–71.

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the participants of the Iwate Tohoku Medical Megabank project. We would like to thank the staff of the Iwate Tohoku Medical Megabank Organization of Iwate Medical University for their encouragement and support. We deeply thank Yuko Funaba, Rin Sugimoto, Tomoko Niisato, and Mikiko Yoshida for their assistance with data collection, data cleaning, and dataset creation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Reconstruction Agency, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (MEXT), and the Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (grant no. JP20km0105003j0009 and JP21tm0124006). The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: Y.K. and K.T. Acquisition and analysis of data: Y.K. and K.T. Reviewed the analysis processes and data interpretation and edited the manuscript: Y.K., K.T., K.O., R.S., and M.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1991), written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Ethics Committee of Iwate Medical University (first approval: HG H25-2; most recent approval: HG 2018-004) approved all the study procedures. The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1991).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflicts of interest in association with this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kotozaki, Y., Tanno, K., Otsuka, K. et al. Longitudinal changes in depressive symptoms associated with social isolation after the Great East Japan Earthquake in Iwate Prefecture: findings from the TMM CommCohort study. BMC Public Health 23, 1154 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16082-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16082-z