Abstract

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic increases the risk of psychological problems, especially for the infected population. Sleep disturbance and feelings of defeat and entrapment are well-documented risk factors of anxiety symptoms. Exploring the psychological mechanism of the development of anxiety symptoms is essential for effective prevention. This study aimed to examine the mediating effects of entrapment and defeat in the association between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers in Shanghai, China.

Methods

A cross-sectional study was conducted from March to April, 2022. Participants were 1,283 asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers enrolled from the Ruijin Jiahe Fangcang Shelter Hospital, Shanghai (59.6% male; mean age = 39.6 years). Questionnaire measures of sleep disturbance, entrapment, defeat, anxiety symptoms, and background characteristics were obtained. A mediation model was constructed to test the mediating effects of entrapment and defeat in the association between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms.

Results

The prevalence rates of sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms were 34.3% and 18.8%. Sleep disturbance was positively associated with anxiety symptoms (OR [95%CI] = 5.013 [3.721–6.753]). The relationship between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms (total effect: Std. Estimate = 0.509) was partially mediated by entrapment (indirect effect: Std. Estimate = 0.129) and defeat (indirect effect: Std. Estimate = 0.126). The mediating effect of entrapment and defeat accounted for 50.3% of the association between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms.

Conclusion

Sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms were prevalent among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers. Entrapment and defeat mediate the association between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms. More attention is needed to monitoring sleep conditions and feelings of defeat and entrapment to reduce the risk of anxiety.

Highlights

A cross-sectional study was conducted among 1,283 asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers during the 2022 SARS-CoV-2 Omicron outbreak in Shanghai.

Asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers had a high risk of developing anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance during the pandemic.

Feelings of entrapment and defeat mediated the association between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) is widespread worldwide and has been defined by the World Health Organization as a severe public health emergency. The COVID-19 outbreak poses a great threat to public health, bringing with it a considerable burden of mental health problems. During the COVID-19 pandemic, there has been a significant increase in global mental health disorders, with depression and anxiety increasing by 27.6% and 25.6% respectively [1]. In addition, mental health problems were even more severe among those infected with COVID-19 compared to the general population [2]. A previous meta-analysis suggests that coronavirus infection can lead to a range of psychiatric disorders such as delirium, anxiety, depression, and insomnia [3]. In a cohort study among 68 million individuals in the USA, survivors of the COVID-19 had a higher risk of developing psychiatric sequelae [4]. Another survey in China at the beginning of the pandemic revealed the psychological impacts of the outbreak, with 28.8% of the population reporting moderate to severe anxiety symptoms [5]. In contrast, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms was higher in COVID-19 patients [6].

Several studies have focused on the etiology and risk factors of anxiety symptoms in people with COVID-19, finding that gender, age, marital status, COVID-19 disease duration, family infection, oxygen saturation levels, etc. were associated with anxiety symptoms [7, 8]. However, to facilitate effective psychological interventions in this population, there is a need to explore modifiable risk factors of anxiety symptoms. Sleep disturbance, another mental health problem prevalent in the context of the pandemic, could play a significant role in the development of anxiety symptoms [9]. Previous studies have demonstrated that sleep disturbance is a critical influencing factor of anxiety symptoms in people with COVID-19 [10, 11].

To better understand the relationship between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms, previous studies have explored the mediators linking these two disorders. Possible mediators included stress [12], personal sleep debt and daytime sleepiness [13], and cognitive complaints [14]. The Social Rank Theory proposes low mood and submissive behavior as involuntary adaptive responses to adverse situations. If the situations remain unchanged or inescapable, the adaptive responses will become maladaptive and eventually lead to serious pathology [15]. Entrapment (feelings of failed social struggle) and defeat (inability to escape from a situation) represent the key maladaptive stress responses in the process [16], which may underly the relationship between unfavorable sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms. First, perceptions of defeat and entrapment have been identified as important precursors of different types of psychiatric disorders [17]. Previous studies showed that entrapment and defeat are closely related to anxiety symptoms [18, 19]. Furthermore, according to the Cry of Pain model, disturbed sleep could act as a stressor, triggering feelings of entrapment and defeat [20]. Although the relationship among sleep disturbance, entrapment, defeat, and anxiety symptoms remains unclear, previous studies have investigated the mediating effects of entrapment and defeat on the associations between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation, a more severe type of mental disorder [21, 22]. Similarly, we hypothesized that sleep disturbance could also increase the risk of anxiety symptoms through the mediating effects of entrapment and defeat.

Compared to the general population, evidence is limited on the mental health problems of the people with COVID-19. To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet explored the psychological mechanisms underlying the development of anxiety symptoms in this population. Therefore, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of anxiety symptoms, sleep disturbance, defeat, and entrapment in a group of asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers during the 2022 SARS-CoV-2 Omicron outbreak in Shanghai, when the SARS-CoV-2 were highly infectious but caused significantly lower mortality than the first wave of the outbreak in 2020 [23]. The aims of this study were: (1) to investigate the prevalence of sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms in asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers in Shanghai, China; (2) to explore the mediating relationship between sleep disturbance, anxiety symptoms, defeat, and entrapment.

Methods

Participants and procedure

The study was conducted from March to April during the 2022 SARS-CoV-2 Omicron outbreak in Shanghai. Participants were asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers enrolled from the Ruijin Jiahe Fangcang Shelter Hospital, Shanghai via convenient sampling. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged 18 years and above; (2) have been diagnosed as asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers, which was confirmed by the threshold Cycle (Ct) value obtained from the real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) test (a Ct value < 35 is considered positive); (3) consent to participate in the study (4) able to use a smartphone to complete the questionnaire independently. Self-reported questionnaires were completed through the online survey platform “Questionnaire Star” and then distributed via Wechat.

Measurements

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI)

The PSQI is a 19-item self-rated scale that measures seven components of sleep quality over the past month: subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, habitual sleep efficiency, sleep disturbances, use of sleeping medication, and daytime dysfunction [24]. The summed component scores yield a global score ranging from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating poorer sleep quality. According to the recommended cut-off in the original study, a global score > 5 represents poor sleep quality [24]. The use of the PSQI in the Chinese adult population to assess sleep quality has been validated by previous studies with acceptable psychometric robustness and validated factor structure [25, 26].

Entrapment Scale (ES)

The 16-item ES was designed by Gilbert and Allan to evaluate the extent an individual feels imprisoned or trapped by unbearable thoughts, feelings, or circumstances [15]. The response of each item was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (“not at all like me”) to 4 (“extremely like me”). Total scores of the ES range from 0 to 64, and higher scores indicate greater feelings of entrapment. Previous studies have demonstrated that the Chinese version of the ES had good reliability with a one-dimensional structure among men who have sex with men [27] and a two-dimensional structure among migrant workers [28]. The scale has also exhibited good internal consistency among college students (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.93–0.94) [29]. Cronbach’s alpha value for the scale was 0.976 in the present study.

Defeat Scale (DS)

The 16-item DS was designed by Gilbert and Allan to measure the sense of failed struggle and low social rank [15]. The response of each item was assessed on a 5-point Likert scale from 0 (“never”) to 4 (“always”). Total scores of the DS range from 0 to 64, and higher scores indicate more easily feeling defeat in daily life. The Chinese version of the DS has exhibited good internal consistency among college students (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.933), preferring a two-dimensional structure including decadence and low sense of achievement [30]. Cronbach’s alpha value for the scale was 0.912 in the present study.

Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS)

The 20-item SAS is an instrument for assessing individuals’ subject feelings of anxiety responding [31]. The response of each item was rated on a 4-point Likert scale from 1 (“none or a little of the time”) to 4 (“most of the time”). Total raw scores of the SAS range from 20 to 80, with higher scores representing more severe anxiety symptoms. The standard scores are produced by the raw scores multiplied by 1.25 (range from 25 to 100). The presence of anxiety was defined as standard scores > 50 [31]. The Chinese version of the SAS is reliable and well-validated [32]. The scale has also exhibited good internal consistency among elderly caregivers and college students (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.820–0.896) [33, 34]. Cronbach’s alpha value for the scale was 0.821 in the present study.

Background characteristics

Background characteristics included gender (male; female), age (18 ~ 34 years, 35 ~ 49 years, 50 ~ 71 years), education level (junior high school and below, college and above), marital status (unmarried, married, divorced, or widowed), days since diagnosis (≤ 7 days, 8 ~ 14 days, ≥ 8 days), and whether they stayed with families (yes, no).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were first conducted for sociodemographic characteristics and the prevalence of sleep quality and anxiety symptoms. As the distribution of SAS scores was skewed, rank-sum tests were used to compare the SAS scores across different groups. Participants were categorized into two groups based on SAS scores: Anxiety and non-anxiety. Univariable logistic regressions were then performed to examine the associations between background variables and anxiety symptoms. Moreover, pairwise correlation analyses of the measurements (PSQI for sleep quality, entrapment scale for entrapment, defeat scale for defeat, and SAS for anxiety symptoms) were conducted to investigate the relationship among these variables.

Finally, the hypothetic mediation model for sleep quality, entrapment, defeat, and anxiety symptoms was tested using Preacher and Hayes’s method [35]. Bootstrapping analysis with 5000 resamples was conducted to derive bias-corrected 95% confidence intervals (CI). The weighted least squares and mean and variance estimator was used as the outcome was categorical. The significant background variables of anxiety symptoms were controlled in the mediation model. Goodness-of-fit of the model was evaluated by a series of model fit indices (root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA], comparative fit index [CFI], Tucker–Lewis index [TLI], standardized root mean square residual [SRMR]). RMSEA < 0.08, CFI > 0.90, TLI > 0.90, and SRMR < 0.08 indicated acceptable goodness-of-fit. P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Mplus.

Ethic

This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine. All subjects consented to participate in this study and provided their written informed consent.

Results

Descriptive analyses

As shown in Table 1, the final sample consisted of 765 males (59.6%) and 518 females (40.4%), ranging in age from 18 to 71 years (mean age = 39.6 ± 11.1 years). Most participants (73.9%, n = 948) were married, and 70.6% (n = 906) had an educational level of junior high school and below. Since the diagnosis of COVID-19, approximately half (50.4%, n = 646) of the participants had passed 8 ~ 14 days, and 65.9% (n = 846) did not stay with their family members. The prevalence rates of anxiety symptoms and sleep disturbance were 18.8% (n = 241) and 34.3% (n = 440), respectively.

Of these sociodemographic factors, education level (p = 0.007) and whether the participants stayed with their families (p = 0.035) were significantly associated with anxiety symptoms. In addition, poor sleepers had a higher risk of developing anxiety symptoms compared with good sleepers (OR [95%CI] = 5.013 [3.721–6.753]).

Correlation analyses

The median and upper and lower quartiles of the PSQI score, ES score, DS score, and SAS score were 4 (2–7), 17 (16–26), 28 (24–35), and 35 (29–37), respectively. The results of correlation analyses were presented in Table 2. There were positive and significant correlations among sleep disturbance, entrapment, defeat, and anxiety symptoms (p < 0.001).

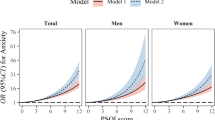

Mediation analyses

As shown in Table 3 and Fig. 1, there was a significant total effect of sleep disturbance on anxiety symptoms (Standardized estimate [Std. estimate] = 0.509, p < 0.001) after adjusting for education level and whether the participants stayed with their families. When mediated through entrapment and defeat, the indirect effect of sleep disturbance on anxiety symptoms remained significant (Std. estimate = 0.253, p < 0.001). In addition, the indirect effect of sleep disturbance on anxiety symptoms through entrapment (Std. estimate = 0.129, p = 0.001) and defeat (Std. estimate = 0.126, p < 0.001) were both significant. Overall, the mediating effect of entrapment and defeat accounted for 50.3% (0.256/0.509 [Std. estimate of indirect effect/Std. estimate of total effect]) of the association between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms.

The proposed mediation model showed acceptable goodness of fit (CFI = 0.991, TLI = 0.973, RMSEA = 0.058, SRMR = 0.069). All path coefficients in the model had p values < 0.05.

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the prevalence of sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers in Shanghai, China, as well as to elucidate the role of entrapment and defeat underlying the association between these two psychological disorders. In this study, the prevalence rates of sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms were 34.3% and 18.8%, respectively. Sleep disturbance could increase the risk of anxiety symptoms through the mediating effects of entrapment and defeat.

A total of 18.8% of the asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers experienced anxiety symptoms in the present study, which is similar to the prevalence rates (16.6%) previously reported in COVID-19 patients and healthcare workers who had a history of exposure [36, 37]. In contrast, moderate-to-severe anxiety was significantly less prevalent in the general population in China during the pandemic [38]. Although the severity of psychological problems varied across different stages of the pandemic, people with COVID are consistently vulnerable to anxiety symptoms. The high risk of anxiety symptoms in asymptomatic carriers, despite the absence of physical disorder, might be attributed to their fear of illness, experience of being stigmatized, and social isolation during quarantine [39]. A previous longitudinal study has shown that social isolation was among the determinants of widespread stress during the pandemic, which in turn resulted in impaired mental health [40].

Moreover, the prevalence of anxiety symptoms (35.7%) was even higher in the poor sleeper group. Compared to the asymptomatic carriers with normal sleep quality, the individuals with sleep disturbance had a higher risk of developing anxiety symptoms (OR [95%CI] = 5.013 (3.721–6.753)). This is consistent with previous findings that sleep disturbance is positively associated with the severity of anxiety symptoms during the pandemic [9]. Sleep disturbance could increase the risk of anxiety through a shared and mutually reinforcing neurocircuitry involving dopamine, serotonin, and adenosine [41]. Additionally, sleep could act as a moderator in the relationship between external stress and anxiety symptoms [37]. Therefore, as a modifiable factor, sleep conditions have significant potential in reducing anxiety symptoms, especially among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers who are exposed to a number of psychosocial risk factors [42].

We found that participants with an education level of college and above reported a lower level of anxiety symptoms (p = 0.007). This is similar to previous findings that education attainment plays a protective role in mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic [43]. Our result also indicated that individuals who stayed with their families after being diagnosed with COVID-19 had a lower risk of developing anxiety symptoms (OR [95%CI] = 1.395 [1.025–1.898]). In contrast, those without family companions have reduced social interactions and are more likely to feel helpless in response to the pandemic. Several previous studies have revealed that living alone during the pandemic is a significant risk factor for anxiety symptoms in the adult population [44, 45]. The present study further demonstrated the need for family support among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers to prevent anxiety symptoms.

After adjusting for education level and whether they stayed with families, feelings of entrapment and defeat mediated the association between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms in asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers. Although there is evidence regarding the mediating role of entrapment and defeat in the relationship between sleep disturbance and suicidal ideation [21, 22], no study has examined this psychological mechanism for less severe but more prevalent anxiety symptoms. Our results showed significant mediating effects of entrapment (25.3%) and defeat (24.8%) between the association of sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms. Although the nature of the association of sleep disturbance with defeat and entrapment remains unclear, individuals with disturbed sleep may tend to experience daily difficulties with cognitive, emotional, interpersonal, and physical functioning, resulting in poorer quality of life and stronger feelings of being defeated [21]. Meanwhile, the difficulties in initiating or maintaining sleep block the escape route from daily problems through sleep, causing poor sleepers to feel trapped by their own thoughts or external environment [46]. The feelings of entrapment and defeat could subsequently increase the risks of anxiety symptoms [47].

Currently, studies of the mediation model of the associations between sleep disturbance, entrapment, defeat, and anxiety symptoms are new in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. To the best of our knowledge, there is no study to examine the psychological mechanism underlying the development of anxiety symptoms in asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers, a vulnerable group at risk of psychological disorders during the pandemic. Our study identified sleep disturbance as a modifiable risk factor that could affect anxiety symptoms by increasing the feelings of defeat and entrapment. Therefore, interventions are needed for the asymptomatic carriers experiencing sleep disturbance. For example, cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBTi), a psychological treatment that can be delivered in non-clinical environment [48], can be used to reduce the potential risk of anxiety symptoms among poor sleepers. In addition, considering the mediating effects of entrapment and defeat in the relationship between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms, it’s necessary to monitor the levels of defeat and entrapment among those with sleep disturbance. Early identification and relief of defeat and entrapment may effectively block the effects of sleep disturbance on anxiety symptoms. Psychological counseling and support can benefit from boosting coping strategies that address the feelings of difficulties and frustration, preventing long-term mental health outcomes in poor sleepers [49].

The present study has several limitations. First, we should be cautious in drawing causal conclusions due to the cross-sectional study design. Longitudinal studies are needed to establish the temporal relationship between sleep disturbance, entrapment, defeat, and anxiety symptoms. Second, we relied on self-reported measures, which may be affected by recalling bias or socially desirable responses. However, given the sample size and the research setting of the present study, it’s acceptable to use the validated and frequently used self-reported scale (i.g. PSQI, ES, DS, and SAS) to measure the studied variables. In addition, we ensured information confidentiality to maximize the reliability and accuracy of the responses as possible. Third, in addition to the two mediators investigated in this study, other factors may also be critical in linking sleep disturbance to anxiety symptoms. For example, resilience was found to mediate the association between sleep disturbance and mental health problems [50]. Further exploration of multiple mediating effects could contribute to a better understanding of the pathway.

Conclusions

This study is the first to explore the relationship among sleep disturbance, entrapment, defeat, and anxiety symptoms in asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers. In the present study, sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms were prevalent among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers. We also found that entrapment and defeat mediate the association between sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms. We recommend that monitoring of sleep conditions and feelings of defeat and entrapment be strengthened to prevent anxiety in vulnerable populations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Change history

15 June 2023

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-16064-1

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease-19

- PSQI:

-

Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index

- ES:

-

Entrapment Scale

- DS:

-

Defeat Scale

- SAS:

-

Self-rating Anxiety Scale

- RMSEA:

-

Root mean square error of approximation

- CFI:

-

Comparative fit index

- TLI:

-

Tucker–Lewis index

- SRMR:

-

Standardized root mean square residual

References

COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398(10312):1700–12.

Wu T, Jia X, Shi H, Niu J, Yin X, Xie J, et al. Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;281:91–8.

Rogers JP, Chesney E, Oliver D, Pollak TA, McGuire P, Fusar-Poli P, et al. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: a systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):611–27.

Taquet M, Luciano S, Geddes JR, Harrison PJ. Bidirectional associations between COVID-19 and psychiatric disorder: retrospective cohort studies of 62 354 COVID-19 cases in the USA. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8(2):130–40.

Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, Tan Y, Xu L, Ho CS, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(5):1729.

Li L, Wu MS, Tao J, Wang W, He J, Liu R, et al. A follow-up investigation of mental health among discharged COVID-19 patients in Wuhan. China Front Public Health. 2021;9: 640352.

Li T, Sun S, Liu B, Wang J, Zhang Y, Gong C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for anxiety and depression in patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan. China Psychosom Med. 2021;83(4):368–72.

Saidi I, Koumeka PP, AitBatahar S, Amro L. Factors associated with anxiety and depression among patients with Covid-19. Respir Med. 2021;186: 106512.

Eleftheriou A, Rokou A, Arvaniti A, Nena E, Steiropoulos P. Sleep quality and mental health of medical students in greece during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2021;9: 775374.

Fu L, Fang Y, Luo D, Wang B, Xiao X, Hu Y, et al. Pre-hospital, in-hospital and post-hospital factors associated with sleep quality among COVID-19 survivors 6 months after hospital discharge: cross-sectional survey in five cities in China. BJPsych Open. 2021;7(6): e191.

Scarpelli S, Nadorff MR, Bjorvatn B, Chung F, Dauvilliers Y, Espie CA, et al. Nightmares in people with COVID-19: Did Coronavirus infect our dreams? Nat Sci Sleep. 2022;14:93–108.

Zhang WJ, Yan C, Shum D, Deng CP. Responses to academic stress mediate the association between sleep difficulties and depressive/anxiety symptoms in Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2020;263:89–98.

Dickinson DL, Wolkow AP, Rajaratnam SMW, Drummond SPA. Personal sleep debt and daytime sleepiness mediate the relationship between sleep and mental health outcomes in young adults. Depress Anxiety. 2018;35(8):775–83.

Toyoshima K, Ichiki M, Inoue T, Shimura A, Masuya J, Fujimura Y, et al. Cognitive complaints mediate the influence of sleep disturbance and state anxiety on subjective well-being and ill-being in adult community volunteers: a cross sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):566.

Gilbert P, Allan S. The role of defeat and entrapment (arrested flight) in depression: an exploration of an evolutionary view. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):585–98.

Wetherall K, Robb KA, O’Connor RC. Social rank theory of depression: a systematic review of self-perceptions of social rank and their relationship with depressive symptoms and suicide risk. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:300–19.

Sloman L, Gilbert P, editors. Subordination and Defeat: an evolutionary approach to mood disorders and their therapy. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2000.

Taylor PJ, Gooding P, Wood AM, Tarrier N. The role of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety, and suicide. Psychol Bull. 2011;137(3):391–420.

Gilbert P, Allan S, Brough S, Melley S, Miles JN. Relationship of anhedonia and anxiety to social rank, defeat and entrapment. J Affect Disord. 2002;71(1–3):141–51.

Littlewood DL, Gooding PA, Panagioti M, Kyle SD. Nightmares and suicide in posttraumatic stress disorder: the mediating role of defeat, entrapment, and hopelessness. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(3):393–9.

Russell K, Rasmussen S, Hunter SC. Insomnia and nightmares as markers of risk for suicidal ideation in young people: investigating the role of defeat and entrapment. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(5):775–84.

Bradford DRR, Biello SM, Russell K. Defeat and entrapment mediate the relationship between insomnia symptoms and suicidal ideation in young adults. Arch Suicide Res. 2022;26(3):1632–43.

Chen X, Yan X, Sun K, Zheng N, Sun R, Zhou J, et al. Estimation of disease burden and clinical severity of COVID-19 caused by Omicron BA.2 in Shanghai. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11(1):2800–7.

Buysse DJ, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Berman SR, Kupfer DJ. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: a new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28(2):193–213.

Zhang C, Zhang H, Zhao M, Li Z, Cook CE, Buysse DJ, et al. Reliability, validity, and factor structure of pittsburgh sleep quality index in community-based centenarians. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11: 573530.

Ho KY, Lam KKW, Xia W, Chung JOK, Cheung AT, Ho LLK, et al. Psychometric properties of the Chinese version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) among Hong Kong Chinese childhood cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19(1):176.

Xu C, Yu X, Tsamlag L, Zhang S, Chang R, Wang H, et al. Evaluating the validity and reliability of the Chinese entrapment scale and the relationship to depression among men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):328.

Long R, Chen H, Hu T, Chen Y, Cao B, Wang R, et al. The association between entrapment and depression among migrant workers in China: a social rank theory based study. BMC Psychiatry. 2022;22(1):17.

Gong R, Liu J, Wang Y, Cai Y, Wang S. Validity and reliability of the Chinese vision of the entrapment scale in medical students. Chin Ment Health J. 2019;33(5):393–7.

Tang H, Wang S, Gong R, Wang Z, Cai Y. Reliability and validity of defeat scale on anxiety and depression in medical students. J Shanghai Jiao Tong Univ (Medical Science). 2019;39(1):84–8.

Zung WW. A rating instrument for anxiety disorders. Psychosomatics. 1971;12(6):371–9.

Self-rating Anxiety Scale. In: Wang XD, Wang XL, Ma H, editors. Handbook of psychological mental health assessment (supplement). Beijing: Chinese Mental Health Periodical Agency; 1999. p. 210–1.

Yang Z, Jia H, Lu Y, Liu S, Dai M, Zhang H. Prevalence and related factors of depression and anxiety in a cohort of Chinese elderly caregivers in the nursing home. J Affect Disord. 2021;295:1456–61.

Zhang G, Yang X, Tu X, Ding N, Lau JTF. Prospective relationships between mobile phone dependence and mental health status among Chinese undergraduate students with college adjustment as a mediator. J Affect Disord. 2020;260:498–505.

Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40(3):879–91.

Dong F, Liu HL, Dai N, Yang M, Liu JP. A living systematic review of the psychological problems in people suffering from COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2021;292:172–88.

Magnavita N, Tripepi G, Di Prinzio RR. Symptoms in health care workers during the COVID-19 epidemic. A cross-sectional survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(14):5218.

Shi L, Lu ZA, Que JY, Huang XL, Liu L, Ran MS, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors associated with mental health symptoms among the general population in China during the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(7):e2014053.

Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–20.

Magnavita N, Soave PM, Antonelli M. Prolonged stress causes depression in frontline workers facing the COVID-19 pandemic-a repeated cross-sectional study in a COVID-19 hub-hospital in Central Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(14):7316.

Chellappa SL, Aeschbach D. Sleep and anxiety: From mechanisms to interventions. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;61: 101583.

Chen H, Chen Y, Zhang Y, Wang Z, Shi D, Liu J, et al. Social stigma and depression among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers in Shanghai, China: the mediating role of entrapment and decadence. LID - https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013006 [doi] LID - 13006. (1660–4601 (Electronic)).

Kunzler AM, Röthke N, Günthner L, Stoffers-Winterling J, Tüscher O, Coenen M, et al. Mental burden and its risk and protective factors during the early phase of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic: systematic review and meta-analyses. Global Health. 2021;17(1):34.

Qi T, Hu T, Ge QQ, Zhou XN, Li JM, Jiang CL, et al. COVID-19 pandemic related long-term chronic stress on the prevalence of depression and anxiety in the general population. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):380.

Watkins-Martin K, Orri M, Pennestri MH, Castellanos-Ryan N, Larose S, Gouin JP, et al. Depression and anxiety symptoms in young adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: evidence from a Canadian population-based cohort. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):42.

Winsper C, Tang NK. Linkages between insomnia and suicidality: prospective associations, high-risk subgroups and possible psychological mechanisms. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2014;26(2):189–204.

Siddaway AP, Taylor PJ, Wood AM, Schulz J. A meta-analysis of perceptions of defeat and entrapment in depression, anxiety problems, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicidality. J Affect Disord. 2015;184:149–59.

Espie CA, Emsley R, Kyle SD, Gordon C, Drake CL, Siriwardena AN, et al. Effect of digital cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia on health, psychological well-being, and sleep-related quality of life: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiat. 2019;76(1):21–30.

Gooding P, Tarrier N, Dunn G, Shaw J, Awenat Y, Ulph F, et al. The moderating effects of coping and self-esteem on the relationship between defeat, entrapment and suicidality in a sample of prisoners at high risk of suicide. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(8):988–94.

Zhao L, Yang F, Sznajder KK, Zou C, Jia Y, Yang X. Resilience as the mediating factor in the relationship between sleep disturbance and post-stroke depression of stroke patients in China: a structural equation modeling analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12: 625002.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all the patients who participated in this study and Pro. Liping Qiu and all the members of the Ruijin Jiahe Fangcang Shelter Hospital for their hard work.

Funding

This work was support by the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission [grant numbers GWV-10.1-XK18] and the Science and Technology Commission Shanghai Municipality (No. 20JC1410204) for the Seroepidemiological Study of Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia in Key Populations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design: YC, JL; Data collection: JL, XY; Data curation: XY, SW, DS; Writing – original draft: YL, XG, JZ; Formal analysis: YL, FH; Writing – review and editing: LX, YC, DS. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration. This study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Ruijin Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (LL202270). All subjects consented to participate in this study and provided their written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article has been updated to correct the funding information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Y., Ge, X., Zhang, J. et al. Sleep disturbance and anxiety symptoms among asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers in Shanghai, China: the mediating role of entrapment and defeat. BMC Public Health 23, 993 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15803-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15803-8