Abstract

Background

Men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men are disproportionately affected by health conditions associated with increased risk of severe illness due to COVID-19 infection.

Methods

An online cross-sectional survey of men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men in the UK recruited via social networking and dating applications from 22 November-12 December 2021. Eligible participants included self-identifying men, transgender women, or gender-diverse individuals assigned male at birth (AMAB), aged ≥ 16, who were UK residents, and self-reported having had sex with an individual AMAB in the last year. We calculated self-reported COVID-19 test-positivity, proportion reporting long COVID, and COVID-19 vaccination uptake anytime from pandemic start to survey completion (November/December 2021). Logistic regression was used to assess sociodemographic, clinical, and behavioural characteristics associated with SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) test positivity and complete vaccination (≥ 2 vaccine doses).

Results

Among 1,039 participants (88.1% white, median age 41 years [interquartile range: 31-51]), 18.6% (95% CI: 16.3%-21.1%) reported COVID-19 test positivity, 8.3% (95% CI: 6.7%-10.1%) long COVID, and 94.5% (95% CI: 93.3%-96.1%) complete COVID-19 vaccination through late 2021. In multivariable models, COVID-19 test positivity was associated with UK country of residence (aOR: 2.22 [95% CI: 1.26-3.92], England vs outside England) and employment (aOR: 1.55 [95% CI: 1.01-2.38], current employment vs not employed). Complete COVID-19 vaccination was associated with age (aOR: 1.04 [95% CI: 1.01-1.06], per increasing year), gender (aOR: 0.26 [95% CI: 0.09-0.72], gender minority vs cisgender), education (aOR: 2.11 [95% CI: 1.12-3.98], degree-level or higher vs below degree-level), employment (aOR: 2.07 [95% CI: 1.08-3.94], current employment vs not employed), relationship status (aOR: 0.50 [95% CI: 0.25-1.00], single vs in a relationship), COVID-19 infection history (aOR: 0.47 [95% CI: 0.25-0.88], test positivity or self-perceived infection vs no history), known HPV vaccination (aOR: 3.32 [95% CI: 1.43-7.75]), and low self-worth (aOR: 0.29 [95% CI: 0.15-0.54]).

Conclusions

In this community sample, COVID-19 vaccine uptake was high overall, though lower among younger age-groups, gender minorities, and those with poorer well-being. Efforts are needed to limit COVID-19 related exacerbation of health inequalities in groups who already experience a greater burden of poor health relative to other men who have sex with men.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) was first detected in the United Kingdom (UK) in January 2020. Through December 2021, the number of cases surpassed 13.5 million [1], as the UK experienced multiple COVID-19 waves [2]. Intermittent national lockdowns were put into place from March 2020 with substantial easing of public health measures in July/August 2021.

The national COVID-19 vaccination programme began in December 2020, where roll-out of two-dose vaccination schedules were prioritised for older adults and those with clinical vulnerability, which included people living with HIV (PLWHIV) if immune function was weakened [3]. By June 2021, all adults aged ≥ 18 had access to a first dose, while booster doses (i.e. a third vaccine dose) were available to select priority groups from September 2021, with wider availability to all adults from December 2021 [4].

In England, the age-standardised percentage of double-vaccinated adults peaked at 86.9% from December 2021 through May 2022 (85.4% in men) [5]. Despite high vaccination levels, national surveillance suggests inequalities in vaccination uptake where, among men, vaccination remains highest in those of White British ethnicity (88.0% by May 2022), and lowest in men of Black African (68.3%) and Black Caribbean (56.3%) ethnicities.

To date, increased COVID-19 related clinical severity and mortality in the UK have been described among men, people of Black or Asian ethnicity, and PLWHIV [6,7,8,9]. The prevalence of long COVID, described as the continuation or development of new symptoms following initial COVID-19 infection [10] and considered an emerging public health challenge, was estimated in 2% of UK men in January 2022 [11].

As COVID-19 continues to widen health inequalities in the UK [7], it is unclear to what extent COVID-19 has impacted men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men. Despite being disproportionately affected by health conditions associated with increased risk of severe illness due to COVID-19 infection [12, 13], available COVID-related literature for men who have sex with men has primarily focused on changing sexual risk and behaviours following COVID-associated lockdowns.

Given this lack of evidence and the opportunity to examine further intersectional inequalities, we used data from the most recent round of the “Reducing inequalities in Sexual Health (RiiSH)-COVID” survey, part of a series of large, online UK-based community surveys, to assess self-reported COVID-19 test positivity and prevalence of long COVID, as well as self-reported COVID-19 vaccination uptake in men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men.

Methods

The RiiSH-COVID surveys are a series of four, online, cross-sectional surveys assessing the impact of COVID-19 and related restrictions on health and wellbeing, sexual behaviour, and service-use among a community sample of men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men in the UK. Each round was fielded during different stages of the pandemic, where the fourth round, and data source for this paper, was deployed from 22 November–12 December 2021. Survey methodology and recruitment through social networking and geospatial dating applications have been previously described [14, 15]. Briefly, eligible participants included self-identifying men (cisgender/transgender), transgender women, or gender-diverse individuals assigned male at birth (AMAB), aged ≥ 16, UK residents, who self-reported having had sex with a man (cisgender/transgender) or gender-diverse individual AMAB in the last year. Online consent was obtained from all participants and no incentive was offered to participate.

Statistical analyses

COVID-19 positivity and long COVID history

COVID-19 test positivity was calculated among those who, from pandemic start through survey completion (November/December 2021), ever self-reported having a swab (PCR [virus] or lateral flow test [antigen]) or blood (antibody) test (where an antibody test was prior to vaccination in those vaccinated). Recent positivity was defined as having a positive test from August-December 2021.

Given differential testing availability over the course of the epidemic in the UK, we undertook a sensitivity analysis examining the prevalence of a COVID-19 infection history based on 1) a self-reported prior positive swab or blood test, or 2) a self-perceived COVID-19 infection in those without a prior positive test or testing history (note, 1 and 2 mutually exclusive).

We calculated the prevalence of self-reported long COVID in all participants, irrespective of COVID-19 test history, modelled on UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimates of self-reported long COVID in representative national surveys [11, 16].

In the cohort of participants asked whether they had experienced long COVID (those with COVID-19 infection history, i.e., self-reported COVID-19 test positivity or self-perception) (Appendix 1), we examined differences (p < 0.05) in sociodemographic, clinical, behaviour and personal well-being characteristics by long COVID self-report using Pearson’s chi-squared and Fisher’s exact tests.

COVID-19 vaccine offer and uptake

COVID-19 vaccine offer and uptake, self-reported anytime during pandemic start through survey completion, was assessed in all participants. Vaccine uptake was defined as the percentage of participants reporting ≥ 1 vaccine dose from pandemic start to survey completion. Complete vaccination (hereafter, complete vaccination) was defined as reporting ≥ 2 vaccine doses.

All calculated percentages in COVID-19 positivity, long COVID, and vaccination uptake outcomes are reported with associated 95% confidence intervals (CI) (Clopper-Pearson).

Factors associated with COVID-19 test positivity and complete COVID-19 vaccination

Using Pearson’s chi-squared test and binary logistic regression, we used separate models to assess factors associated with COVID-19 test positivity and complete COVID-19 vaccination, respectively. Multivariable models were adjusted for covariates where bivariate association was p < 0.10. Evidence of association in multivariable models was considered where p < 0.05. Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios, 95% CIs, and p-values derived from the likelihood ratio test are presented. A sensitivity analysis assessing factors associated with COVID-19 infection history (i.e., test positivity or self-perceived infection) was also carried out.

Covariates used for bivariate and multivariable analyses included sociodemographic characteristics (age-group, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, country of birth, UK country of residence, education-level, employment, household composition [living alone or not], relationship status) and clinical history (HIV status, having a medical condition identified as placing someone at greater risk of severe illness from COVID-19 based on national guidelines [hereafter, known COVID-19 shielding] [3]). Mental health and personal well-being indicators derived from the UK ONS ‘Opinions and Lifestyle Survey’, a weekly survey assessing well-being through the COVID period, were integrated into RiiSH-COVID surveys, and used across analyses. Likert-scale responses (11 point) (“Overall, how anxious did you feel yesterday?” and “Overall, to what extent do you feel the things you do in your life are worthwhile”) were dichotomised to create a measure of high anxiety and low self-worth as per ONS standardisation [17, 18].

Additional covariates included: number of male physical sex partners in the preceding 3–4 month lookback period and PrEP use since first lockdown (i.e. after 23 March 2020), considered transmission risk/behavioural confounders in COVID-19 test positivity and vaccination analyses; self-reported COVID-19 infection history (self-reported test positivity or self-perceived infection) and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination history (self-report of ≥ 1 HPV vaccine doses) used as clinical history and vaccine acceptance indicators in COVID-19 vaccination analyses.

Covariate selection aimed to limit collinearity where multiple covariates were thought to contribute to similar measures (e.g., transmission risk, mental health and well-being, vaccine acceptance indicators). Age and ethnicity were selected a priori for multivariate model inclusion.

Due to limited numbers of participants in gender minority groups (transgender and nonbinary individuals), sexual minority groups (straight and bisexual-identifying individuals), and minority ethnic groups (Black, Asian, other minority ethnic groups), these participants were grouped in analyses.

All analyses were conducted using Stata v.15.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

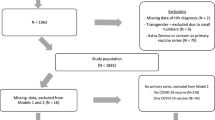

Between 22 November-12 December 2021, 1,039 men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men took part in the fourth RiiSH-COVID survey (Appendix 1, 2). Missing data were limited as most responses were compulsory.

Participants had a median age of 41 (interquartile range [IQR] 31–51). Most were of White ethnicity (88.1%), resided in England (85.6%), and reported current employment (75.7%). Nearly all self-identified as cisgender male (95.7%). Known COVID-19 shielding was reported in 17.8% of participants (43.3% [52/120] in PLWHIV); further description of RiiSH-COVID participants is found in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

COVID-19 positivity and long COVID

Most participants (95.0%) reported having had at least one COVID-19 test from pandemic start through survey completion, where 18.6% (95% CI: 16.3%-21.1%) reported test positivity (median age 37 [IQR: 30–48]) (Table 1, Appendix 1). Nearly half of those reporting a positive test (41.5% [80/193]) reported recent positivity (7.7% of all participants). In our sensitivity analysis, 32.9% (95% CI: 30.0%-35.8%) of all participants reported a COVID-19 infection history (Appendix 1).

Long COVID was self-reported in 8.3% (95% CI: 6.7%-10.1%, n = 86) of all participants. Among the subgroup of participants reporting a COVID-19 infection history (n = 341), those self-reporting long COVID (median age 40 [IQR: 32–53]) were more likely to report prior hospitalisation due to COVID symptoms (8.1% [7/86] vs 2.8% [7/255], p = 0.029) and educational qualifications below degree-level (48.8% [42/86] vs 35.7% [91/255], p = 0.031) relative to those without self-reported long COVID. There were no differences in complete vaccination by self-reported long COVID (90.7% [78/86] vs 92.9% [237/255], p = 0.498) (Table 2).

COVID-19 vaccine offer and uptake

Nearly all participants received a vaccine offer (98.2% [1020/1039]). Complete vaccination was reported by 985 participants (94.8% [95% CI: 93.3%-96.1%]) (Table 3, Appendix 2). Nearly half of all participants reported having had a booster (42.6% [443/1039]; 70.8% [85/120] in PLWHIV).

Factors associated with COVID-19 infection and complete COVID-19 vaccination

Bivariate and multivariable associations with COVID-19 test positivity and complete vaccination are found in Tables 1, 3. For both outcomes, we found no bivariate association by HIV status or country of birth.

Following adjustment in multivariable models, evidence of an association with COVID-19 test positivity was found by UK country of residence (aOR: 2.22 [95% CI: 1.26–3.92], England vs outside England) and employment (aOR: 1.55 [95% CI: 1.01–2.38], current employment vs not employed). There was no evidence of independent association to COVID-19 test positivity by age, ethnicity, or COVID-19 vaccination, though those reporting incomplete vaccination (0–1 doses) were twice as likely to report COVID-19 test positivity relative to those having received 3 vaccine doses (aOR: 2.18 [95% CI: 1.07–4.42]).

The likelihood of complete COVID-19 vaccination increased with age (aOR: 1.04 [95% CI: 1.01–1.06], per increasing year), degree-level or higher educational qualifications (aOR: 2.11 [95% CI: 1.12–3.98], vs below degree-level), current employment (aOR: 2.07 [95% CI: 1.08–3.94], vs not employed), and having a known HPV vaccination (aOR: 3.32 [95% CI: 1.43–7.75]) in adjusted multivariable analysis. Lower likelihood of complete vaccination was seen for gender minority groups (aOR: 0.26 [95% CI: 0.09–0.72], vs cisgender), those with a single relationship status (aOR: 0.50 [95% CI: 0.25–1.00], vs in a relationship), a COVID-19 infection history (aOR: 0.47 [95% CI: 0.25–0.88], vs no history), and the report of low self-worth (aOR: 0.29 [95% CI: 0.15–0.54]).

Discussion

In this large, community sample of men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men, a fifth of participants self-reported testing positive for COVID-19 over the 18 months from pandemic start through late 2021. Across this period, nearly one in ten participants self-reported experiencing long COVID. Complete COVID-19 vaccination was near ubiquitous, as most reported vaccine offer and uptake.

To date, these are the only examinations of COVID-19 positivity outcomes and COVID-19 vaccination uptake among men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men in the UK, important populations who are disproportionately affected by poor health outcomes. While extensive, there was no disaggregate data by gender identity or sexual orientation for our study populations found in UK COVID-19 surveillance outputs. We found few descriptions of COVID-19 outcomes in gender and sexual minorities [19, 20], despite concerted acknowledgement in recognising gender identity as a social health determinant and the need for improved visibility of gender minorities in research and health-reporting [21, 22]. Our study population is broadly representative of prior RiiSH-COVID survey rounds, where fluctuating levels of sexual risk behaviour through the pandemic were reported [15]. Though not wholly comparable, the proportion of participants who self-reported long COVID in this study exceeded the most recently available self-reported estimates in UK men in July 2022 (< 3%) [16].

In our study, those who had ever tested positive for COVID-19 were more likely to live in England and report current employment. Our results likely reflect higher absolute COVID-19 case numbers in England [1], though test positivity varied in the UK through the pandemic [23], and increased case ascertainment facilitated through greater testing accessibility as the pandemic progressed [1]. Higher transmission risk due to greater social mixing, increased in-person working and workplace associated testing as lockdowns had eased, may underpin association to employment. We have no insight as to our survey respondents’ employment type (e.g. public-facing vs working from home), which has been described as a key driver to infection inequalities [7]. To limit misclassification in COVID-19 outcomes, COVID-19 test positivity was utilised in multivariable models given wider circulating respiratory pathogens following lifting of lockdown restrictions [24]. Results from sensitivity analyses incorporating self-perceived infection, show similar direction and magnitude of age and employment related effect estimates, where those with higher educational qualifications and ≥ 2 vaccine doses also had a higher likelihood of an infection history (Appendix 3).

On examining long COVID among the subgroup of participants with a COVID-19 infection history, a higher proportion of those with long COVID self-report, compared to those without, had a prior hospitalisation due to COVID symptoms which may be indicative of infection severity. We found no differences in long COVID by vaccination status, where a recent systematic review suggests reduced risk of long COVID in those vaccinated prior to COVID-19 infection [25]. Given our study design we cannot establish whether reported vaccination preceded infection, a key limitation to interpretation. Unlike a UK-based cohort study of non-hospitalised adults with COVID-19 [26], we found no association between long COVID and age or ethnicity but did find similar socioeconomic inequalities, as those reporting long COVID were less likely to be degree-educated.

Encouragingly, COVID-19 vaccination uptake across participants was high and surpassed population-level estimates of UK men. While our study sample was comprised of younger men relative to the national population [27], complete vaccination exceeded 90% across all age groups. Despite high engagement, age and socioeconomic-related vaccination inequalities were consistent to those nationally reported [5, 28], where participants who were younger, unemployed, and with lower educational qualifications were less likely to report full vaccination despite widespread availability at the time, again suggesting lower levels of deprivation and high health literacy in our sample. We found similar results to an Australian cross-sectional study of gay and bisexual men [29], where COVID-19 vaccination was independently associated with older age and university education in the 28% (358/1280) reporting at least partial vaccination. Unlike this study, however, we found no association to complete COVID-19 vaccination by HIV status, which may be due to differences in vaccination implementation progress in respective study countries. Though age-related uptake differences may reflect the staggered roll-out prioritising older adults, age inequalities have persisted in national surveillance over time following our study period [5].

Our study suggested that HIV status was not associated with COVID-19 test positivity, long COVID, or COVID-19 vaccination in our study population, however, these findings are limited by the relatively small sample size of PLWHIV. Other studies have shown higher likelihood of adverse COVID-related outcomes in PLWHIV [9, 30]. COVID-related restrictions throughout the pandemic may have also affected accessibility to care [31]. In the UK, PLWHIV were considered a priority group for COVID-19 vaccination and a population recommended to shield if immune function was compromised [3]. Among RiiSH-COVID participants living with HIV, we saw a higher proportion of reporting COVID-19 booster vaccine doses, relative to those not known to be HIV positive during the early stages of booster roll-out in the UK. Nearly half of PLWHIV reported shielding, which could have overestimated self-reported shielding in our study sample given high viral suppression noted in the UK [32]; however other co-morbidities experienced by PLWHIV may have contributed to shielding self-report [33].

Similarly, known COVID-19 shielding was not found to be associated with COVID-19 vaccination uptake, COVID-19 test positivity or long COVID outcomes. A national shielding programme was introduced in the UK at the start of the pandemic [3]. We have limited insights to shielding reported in men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men, but levels in our study (17.8%) were similar to those reported in a nationally representative sample of English general practice survey respondents in 2021 (16.9%) [34]. While recommended to minimise infection risk in the extremely clinical vulnerable, studies suggest shielding may have amplified feelings of isolation and contributed to negative effects on mental and physical health [35, 36]. The impact of shielding in men and other gender-diverse individuals should be examined given the risk of compounding mental health inequalities already reported in these groups [37, 38]. Despite their relatively small numbers, further intersectional uptake inequalities, not previously described, were seen in gender minority groups, who also reported the lowest levels of complete vaccination (77.8%). Studies suggest common features of COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy among sexual and gender minority groups that include prior medical trauma, medical mistrust, fear of violence, stigma, and discrimination [39, 40].

Throughout the pandemic, national COVID-19 vaccination efforts sought to minimise structural barriers to uptake, signalling the success of an active, universal vaccination offer with continued accessibility. This contrasts with targeted, often stigma-associated vaccination drives directed to men who have sex with men, where infrequent offer by healthcare staff and infection-associated and population-based stigma have been described as barriers to vaccine uptake [41]. Though our analyses suggest a higher likelihood of COVID-19 vaccination in those reporting HPV vaccination, this should not discount the high levels of complete vaccination in those without. The components underpinning the UK’s COVID-19 vaccination programme, including political will, public buy-in and widespread accessibility, may provide some insights to vaccination efforts for emerging health threats such as mpox [42, 43].

Lastly, we found relationships between mental health and well-being to COVID-19 outcomes. Those reporting low self-worth were less likely to report complete COVID-19 vaccination. While we cannot establish directionality, it is plausible that underlying poor mental health and well-being may have affected vaccination uptake as seen in influenza vaccination studies [44]. However, improvements to mental distress have been reported in adults receiving a first vaccine dose [45]. In longitudinal European analyses, restrictive pandemic policies were associated with poorer mental health [46]. Men who have sex with men have been negatively impacted by the pandemic and related restrictions, with higher levels of anxiety and loneliness reported in those practicing physical distancing, and exacerbated economic, health, and service-use related vulnerabilities [47, 48]. There are similar impacts in transgender and nonbinary individuals as cross-sectional studies suggest disrupted access to gender-affirming care and economic instability brought on by pandemic restrictions has driven poor mental health outcomes [49,50,51]. While qualitative work in the UK [52] indicates that living with a partner a protective factor of well-being, we found no association to COVID-19 vaccination by household composition but see a lower likelihood of vaccination in those reporting a single relationship status. Where possible, longitudinal exploration of upstream and downstream mental health indicators relative to severe COVID-19 outcomes should be explored considering known mental health inequalities among men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men [37] and in absence of vaccine hesitancy guidance for those with mental health difficulties [53].

Limitations

This study adds to the limited data characterising the COVID-19 experience among men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men in the UK, however, there are several limitations. Due to its cross-sectional design, we cannot establish the temporality between survey responses and outcomes and have limited information on the timing of COVID-19 positivity, or potential re-infection, and COVID-19 vaccination, as the recall period for COVID-related outcomes spans the pandemic. Because of this, we are unable to assess the impact of vaccination on COVID-19 infections in our study sample. Responses were self-reported and subject to recall and social desirability bias, though we expect anonymity to have limited this. COVID-19 test positivity could be reflective of symptomatic cases as testing availability and COVID-19 presentation evolved through the pandemic and sensitivity analyses indicate high levels of self-perceived infection (though this is also subject to misclassification given the rapid resurgence of other respiratory pathogens as restrictions eased in the UK). While long COVID outcomes exceeded national estimates, results must be interpreted with caution given the likelihood of differences arising from sampling bias. However, given the disproportionate burden of health conditions associated with the increased risk of severe COVID-19 reported in men who have sex with men, results are plausible, but warrant further examination. Though RiiSH-COVID sought to recruit from across the community in contrast to recruiting from sexual health clinics, it nonetheless may not be generalisable to the wider UK populations of men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men (of which we already have limited insight). For all COVID-19 outcomes, further disaggregate, population-level data by gender (beyond binary norms) and sexual orientation were not available through national COVID-19 surveillance outputs, limiting more refined comparisons.

Survey recruitment was exclusively online to allow rapid data collection across the UK. As such, participants may not include those without internet, though most adults (94%) were estimated to have home-based access in 2021 [54] and cross-sectional work has highlighted the use of online social media for socialisation in men who have sex with men adhering to physical distancing restrictions [47]. Our sample may represent those who may have been more socially active through the recent pandemic, as over two-thirds reported ≥ 2 male physical sex partners in the preceding lookback period. However, this could also be attributable to changes in sexual behaviour following vaccination [55], though studies also suggest higher sexual risk in geospatial dating app users [56].

We found no evidence of age-related inequalities in COVID test positivity and long COVID history, however, further studies assessing intersectional inequalities are needed given variation in COVID-related morbidity and mortality reported in the general population. Analyses in minority ethnic groups, and gender and sexual minorities are limited due to small sample sizes and disaggregate analyses in multivariable models were not possible. We acknowledge the differing health needs and COVID-19 experience among these groups but have included estimates for transparency and future review though they may not be representative of wider groups. However, a strength of this study is the rich insights that RiiSH-COVID provides for these key populations not readily represented in national COVID-19 data outputs. This bolsters the need for regular and enhanced surveys of the community, in parallel to national surveillance, to ensure, equitable, and if needed, targeted pandemic responses.

Conclusions

Findings illustrate high engagement with COVID-19 prevention efforts in our large, community-based sample of men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men, where universal offer and sustained vaccine availability through the pandemic should inform efforts for prevention planning due to the risk of emerging health threats. In the context of mpox prevention, investment in vaccine and clinical services are crucial to reach key populations in need [57]. This study adds insight to the reach and success of the UK’s COVID-19 vaccination programme and a glimpse of COVID-19 infection and long COVID outcomes reported in groups experiencing disproportionate health inequalities. Data collected from RiiSH-COVID are an integral complement to available COVID-19 surveillance.

As the pandemic continues, a systems-level approach should continue to address COVID-19 related knowledge gaps, including vaccine hesitancy, in those engaging with health services and outreach as accessibility rebounds following lifted lockdown restrictions. Among gender minorities, efforts are needed to limit COVID-related exacerbation of health inequalities in those already experiencing greater burden of poor health and service-related stigma relative to other men who have sex with men. Tailored and targeted interventions may be needed to close COVID-19 vaccination uptake gaps to prevent the widening of existing health inequalities due to COVID-19.

Further exploration of COVID-related health outcomes, including long COVID, in men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men are required to identify continued COVID-related impacts and emergence of related health inequalities. The lack of data on these populations in national COVID-19 surveillance and inability to meaningfully benchmark comparisons highlight the importance of integrating sexual orientation and gender identity, where possible, to ensure equitable monitoring and response in the face of new and continuing public health threats.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from University College London (UCL) on reasonable request and with permission from the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA). Requests can be directed to Dr Hamish Mohammed (hamish.mohammed@ukhsa.gov.uk).

Abbreviations

- AMAB:

-

Assigned male at birth

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus Disease 2019

- ONS:

-

Office for National Statistics

- PrEP:

-

HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis

- RiiSH-COVID:

-

‘Reducing inequalities in Sexual Health-COVID’ (survey)

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

References

UK Health Security Agency. Coronavirus (COVID-19) in the UK: Cases in the United Kingdom 2022 [Available from: https://coronavirus.data.gov.uk/details/cases?areaType=overview&areaName=United%20Kingdom.

UK Health Security Agency. COVID-19 variants: genomically confirmed case numbers 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-variants-genomically-confirmed-case-numbers#full-publication-update-history [cited 2022 01 August].

NHS England. COVID-19: guidance for people whose immune system means they are at higher risk 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/covid-19-guidance-for-people-whose-immune-system-means-they-are-at-higher-risk/covid-19-guidance-for-people-whose-immune-system-means-they-are-at-higher-risk [cited 2022 01 August] .

UK Health Security Agency. COVID-19 vaccination programme 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/covid-19-vaccination-programme [cited 2022 01 August].

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. COVID-19 Health Inequalities Monitoring in England tool (CHIME) 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/covid-19-health-inequalities-monitoring-in-england-tool-chime [cited 2022 01 August].

Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) and the different effects on men and women in the UK, March 2020 to February 2021 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19andthedifferenteffectsonmenandwomenintheukmarch2020tofebruary2021/2021-03-10#:~:text=There%20was%20an%20almost%2018,2021%20in%20England%20and%20Wales [cited 2022 01 August].

Public Health England. Disparities in the risk and outcomes of COVID-19 2020. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/908434/Disparities_in_the_risk_and_outcomes_of_COVID_August_2020_update.pdf [cited 2022 01 August].

Takahashi T, Ellingson MK, Wong P, Israelow B, Lucas C, Klein J, et al. Sex differences in immune responses that underlie COVID-19 disease outcomes. Nature. 2020;588(7837):315–20.

Brown AE, Croxford SE, Nash S, Khawam J, Kirwan P, Kall M, et al. COVID-19 mortality among people with diagnosed HIV compared to those without during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in England. HIV Med. 2021;23(1):90–102.

World Health Organization. Post COVID-19 condition (Long COVID) 2022. Available from: https://www.who.int/europe/news-room/fact-sheets/item/post-covid-19-condition [cited 2023 10 January].

Office for National Statistics. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 3 February 2022 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/prevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk/3february2022 [cited 2022 01 August].

Mercer CH, Prah P, Field N, Tanton C, Macdowall W, Clifton S, et al. The health and well-being of men who have sex with men (MSM) in Britain: Evidence from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). BMC Public Health. 2016;16:525.

Heslin KC, Hall JE. Sexual Orientation Disparities in Risk Factors for Adverse COVID-19-Related Outcomes, by Race/Ethnicity - Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2017–2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(5):149–54.

Howarth AR, Saunders J, Reid D, Kelly I, Wayal S, Weatherburn P, et al. ’Stay at home horizontal ellipsis ’: exploring the impact of the COVID-19 public health response on sexual behaviour and health service use among men who have sex with men: findings from a large online survey in the UK. Sex Transm Infect. 2022;98(5):346–52.

Brown JR, Reid D, Howarth AR, Mohammed H, Saunders J, Pulford CV, et al. Changes in STI and HIV testing and testing need among men who have sex with men during the UK’s COVID-19 pandemic response. Sex Transm Infect. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2022-055429.

Office for National Statistics. Prevalence of ongoing symptoms following coronavirus (COVID-19) infection in the UK: 4 August 2022 2022. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/datasets/alldatarelatingtoprevalenceofongoingsymptomsfollowingcoronaviruscovid19infectionintheuk [cited 2022 01 August].

Office for National Statistics. Personal wellbeing harmonised standard 2020. Available from: https://gss.civilservice.gov.uk/policy-store/personal-well-being/ [cited 2022 01 August].

Office for Health Improvement and Disparities. Wider Impacts of COVID-19 on Health (WICH) monitoring tool 2022. Available from: https://analytics.phe.gov.uk/apps/covid-19-indirect-effects/ [cited 2022 01 October].

McGowan VJ, Lowther HJ, Meads C. Life under COVID-19 for LGBT+ people in the UK: systematic review of UK research on the impact of COVID-19 on sexual and gender minority populations. BMJ Open. 2021;11(7): e050092.

Phillips Ii G, Xu J, Ruprecht MM, Costa D, Felt D, Wang X, et al. Associations with COVID-19 Symptoms, Prevention Interest, and Testing Among Sexual and Gender Minority Adults in a Diverse National Sample. LGBT Health. 2021;8(5):322–9.

Pega F, Veale JF. The Case for the World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health to Address Gender Identity. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(3):E58–62.

Logie CH, van der Merwe LLA, Scheim A. Measuring sex, gender, and sexual orientation: one step to health equity. Lancet. 2022;400(10354):715–7.

Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey, UK: 19 August 2022 2022. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/bulletins/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveypilot/19august2022 [cited 2022 25 August].

UK Health Security Agency. National flu and COVID-19 surveillance reports: 2021 to 2022 season 2022. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/national-flu-and-covid-19-surveillance-reports-2021-to-2022-season [cited 2022 01 October].

Notarte KI, Catahay JA, Velasco JV, Pastrana A, Ver AT, Pangilinan FC, et al. Impact of COVID-19 vaccination on the risk of developing long-COVID and on existing long-COVID symptoms: a systematic review. Eclinicalmedicine. 2022;53.

Subramanian A, Nirantharakumar K, Hughes S, Myles P, Williams T, Gokhale KM, et al. Symptoms and risk factors for long COVID in non-hospitalized adults. Nat Med. 2022;28(8):1706–14.

Office for National Statistics. Population estimates 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates [cited 2022 25 September].

Office for National Statistics. Coronavirus (COVID-19) Infection Survey technical article: Analysis of characteristics associated with vaccination uptake 2021. Available from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/conditionsanddiseases/articles/coronaviruscovid19infectionsurveytechnicalarticleanalysisofcharacteristicsassociatedwithvaccinationuptake/2021-11-15 [cited 2022 01 August].

Holt M, MacGibbon J, Bavinton B, Broady T, Clackett S, Ellard J, et al. COVID-19 vaccination uptake and hesitancy in a national sample of Australian gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(8):2531–8.

Bhaskaran K, Rentsch CT, MacKenna B, Schultze A, Mehrkar A, Bates CJ, et al. HIV infection and COVID-19 death: a population-based cohort analysis of UK primary care data and linked national death registrations within the OpenSAFELY platform. Lancet HIV. 2021;8(1):e24–32.

Prabhu S, Poongulali S, Kumarasamy N. Impact of COVID-19 on people living with HIV: A review. J Virus Erad. 2020;6(4): 100019.

UK Health Security Agency. HIV testing, PrEP, new HIV diagnoses, and care outcomes for people accessing HIV services: 2022 report 2022 [Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hiv-annual-data-tables/hiv-testing-prep-new-hiv-diagnoses-and-care-outcomes-for-people-accessing-hiv-services-2022-report.

Morales DR, Moreno-Martos D, Matin N, McGettigan P. Health conditions in adults with HIV compared with the general population: a population-based cross-sectional analysis. eClinicalMedicine. 2022;47:101392.

Ipsos MORI, NHS England. GP Patient survey 2021. Available from: https://www.gp-patient.co.uk/surveysandreports2021 [cited 2023 20 April].

Di Gessa G, Price D. The impact of shielding during the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health: evidence from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Br J Psychiatry. 2022;221(4):637–43.

Lasseter G, Compston P, Robin C, Lambert H, Hickman M, Denford S, et al. Exploring the impact of shielding advice on the wellbeing of individuals identified as clinically extremely vulnerable amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a mixed-methods evaluation. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):2145.

Hickson F, Davey C, Reid D, Weatherburn P, Bourne A. Mental health inequalities among gay and bisexual men in England, Scotland and Wales: a large community-based cross-sectional survey. J Public Health. 2016;39(2):266–73.

Saunders CL, Berner A, Lund J, Mason AM, Oakes-Monger T, Roberts M, et al. Demographic characteristics, long-term health conditions and healthcare experiences of 6333 trans and non-binary adults in England: nationally representative evidence from the 2021 GP Patient Survey. BMJ Open. 2023;13(2): e068099.

Azucar D, Slay L, Valerio DG, Kipke MD. Barriers to COVID-19 vaccine uptake in the LGBTQIA community. Am J Public Health. 2022;112(3):405–7.

Garg I, Hanif H, Javed N, Abbas R, Mirza S, Javaid MA, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy in the LGBTQ plus Population: A Systematic Review. Infectious Disease Reports. 2021;13(4):872–87.

Forster AS, Gilson R. Challenges to optimising uptake and delivery of a HPV vaccination programme for men who have sex with men. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(7–8):1541–3.

Wise J. Monkeypox: UK to run out of vaccine doses by next week. BMJ. 2022;378: o2053.

Bragazzi NL, Khamisy-Farah R, Tsigalou C, Mahroum N, Converti M. Attaching a stigma to the LGBTQI+ community should be avoided during the monkeypox epidemic. J Med Virol. 2023;95(1): e27913.

Lorenz RA, Norris MM, Norton LC, Westrick SC. Factors Associated with influenza vaccination decisions among patients with mental illness. Int Journal of Psychiatr Med. 2013;46(1):1–13.

Perez-Arce F, Angrisani M, Bennett D, Darling J, Kapteyn A, Thomas K. COVID-19 vaccines and mental distress. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(9): e0256406.

Aknin LB, Andretti B, Goldszmidt R, Helliwell JF, Petherick A, De Neve JE, et al. Policy stringency and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a longitudinal analysis of data from 15 countries. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(5):E417–26.

Holloway IW, Garner A, Tan D, Ochoa AM, Santos GM, Howell S. Associations between physical distancing and mental health, sexual health and technology use among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men during the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Homosex. 2021;68(4):692–708.

Santos GM, Ackerman B, Rao A, Wallach S, Ayala G, Lamontage E, et al. Economic, mental health, hiv prevention and hiv treatment impacts of COVID-19 and the COVID-19 response on a global sample of cisgender gay men and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2021;25(2):311–21.

Jarrett BA, Peitzmeier SM, Restar A, Adamson T, Howell S, Baral S, et al. Gender-affirming care, mental health, and economic stability in the time of COVID-19: A multi-national, cross-sectional study of transgender and nonbinary people. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(7): e0254215.

Kia H, Rutherford L, Jackson R, Grigorovich A, Ricote CL, Scheim AI, et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on trans and non-binary people in Canada: a qualitative analysis of responses to a national survey. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1284.

Kidd JD, Jackman KB, Barucco R, Dworkin JD, Dolezal C, Navalta TV, et al. Understanding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of transgender and gender nonbinary individuals engaged in a longitudinal cohort study. J Homosex. 2021;68(4):592–611.

Edelman NL, Witzel TC, Samba P, Nutland W, Nadarzynski T. Mental well-being and sexual intimacy among men and gender diverse people who have sex with men during the first UK COVID-19 lockdown: a mixed-methods study. Int J Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022;19(12):6985.

Smith K, Lambe S, Freeman D, Cipriani A. COVID-19 vaccines, hesitancy and mental health. Evid Based Ment Health. 2021;24(2):47–8.

OFCOM. Online Nation 2022: report 2022. Available from: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/research-and-data/online-research/online-nation [cited 2022 01 October].

Prestage G, Storer D, Jin F, Haire B, Maher L, Philpot S, et al. COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake and Its Impacts in a Cohort of Gay and Bisexual Men in Australia. Aids Behav. 2022;26(8):2692–702.

Wang H, Zhang L, Zhou Y, Wang K, Zhang X, Wu J, et al. The use of geosocial networking smartphone applications and the risk of sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1178.

Reyes-Uruena J, D’Ambrosio A, Croci R, Bluemel B, Cenciarelli O, Pharris A, et al. High monkeypox vaccine acceptance among male users of smartphone-based online gay-dating apps in Europe, 30 July to 12 August 2022. Euro Surveill. 2022;27(42):2200757.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the participants who took part in this study. We acknowledge members of the National Institute for Health and Care Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Blood Borne and Sexually Transmitted Infections (BBSTI) Steering Committee: Professor Caroline Sabin (HPRU Director), Dr John Saunders (UK Health Security Agency Lead), Professor Catherine Mercer, Dr Hamish Mohammed (previously Professor Gwenda Hughes), Professor Greta Rait, Dr Ruth Simmons, Professor William Rosenberg, Dr Tamyo Mbisa, Professor Rosalind Raine, Dr Sema Mandal, Dr Rosamund Yu, Dr Samreen Ijaz, Dr Fabiana Lorencatto, Dr Rachel Hunter, Dr Kirsty Foster and Dr Mamooma Tahir. The authors would like to thank Takudzwa Mukiwa and Ross Purves from the Terrence Higgins Trust for their help with participant recruitment.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Institute for Health and Care Research Health Protection Research Unit (NIHR HPRU) in Blood Borne and Sexually Transmitted Infections at University College London in partnership with the UK Health Security Agency. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care or the UK Health Security Agency.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study design, data collection and data management were carried out by ARH, CHM, GH, JS, HM, DR, JB, and CVP. DO, HA, and HM conceived secondary analysis design with review and contributions from CHM, GH, JS, DR, and JB. DO conducted analyses and wrote the first manuscript draft with contributions from all authors in successive drafts. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval of this study was provided by the UCL Research Ethics Committee (ref: 9155/001). Online informed consent was received from all participants and all methods were performed in accordance with guidelines and regulations set by the UCL Research Ethics Committee.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ogaz, D., Allen, H., Reid, D. et al. COVID-19 infection and vaccination uptake in men and gender-diverse people who have sex with men in the UK: analyses of a large, online community cross-sectional survey (RiiSH-COVID) undertaken November–December 2021. BMC Public Health 23, 829 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15779-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15779-5