Abstract

Background

The persistently high rates of maternal mortality and morbidity among historically marginalised social groups, such as adolescent Scheduled Castes (SCs) and Scheduled Tribes (STs) in India, can be attributed, in part, to the low utilisation of full antenatal healthcare services. Despite efforts by the Indian government, full antenatal care (ANC) usage remains low among this population. To address this issue, it is crucial to determine the factors that influence the utilisation of ANC services among adolescent SC/ST mothers. However, to date, no national-level comprehensive study in India has specifically examined this issue for this population. Our study aims to address this research gap and contribute to the understanding of how to improve the utilisation of ANC services among adolescent SC/ST mothers in India.

Data and methods

Data from the fourth round of the National Family Health Survey 2015–16 (NFHS-4) was used. The outcome variable was full antenatal care (ANC). A pregnant mother was considered to have ‘full ANC’ only when she had at least four ANC visits, at least two tetanus toxoid (TT) injections, and consumed 100 or more iron-folic acid (IFA) tablets/syrup during her pregnancy. Bivariate analysis was used to examine the disparity in the coverage of full ANC. In addition, binary logistic regression was used to understand the net effect of predictor variables on the coverage of full ANC.

Results

The utilisation of full antenatal care (ANC) among adolescent SC/ST mothers was inadequate, with only 18% receiving full ANC. Although 83% of Indian adolescent SC/ST mothers received two or more TT injections, the utilisation of the other two vital components of full ANC was low, with only 46% making four or more ANC visits and 28% consuming the recommended number of IFA tablets or equivalent amount of IFA syrup. There were statistically significant differences in the utilisation of full ANC based on the background characteristics of the participants. The statistical analysis showed that there was a significant association between the receipt of full ANC and factors such as religion (OR = 0.143, CI = 0.044–0.459), household wealth (OR = 5.505, CI = 1.804–16.800), interaction with frontline health workers (OR = 1.821, CI = 1.241–2.670), and region of residence in the Southern region (OR = 3.575, CI = 1.917–6.664).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the study highlights the low utilisation of full antenatal care services among Indian adolescent SC/ST mothers, with only a minority receiving the recommended number of ANC visits and consuming the required amount of IFA tablets/syrup. Addressing social determinants of health and recognising the role of frontline workers can be crucial in improving full ANC coverage among this vulnerable population. Furthermore, targeted interventions tailored to the unique needs of different subgroups of adolescent SC/ST mothers are necessary to achieve optimal maternal and child health outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

The Indian population can be divided into two broad groups: the mainstream and indigenous populations. The caste system, a rigid and discriminatory social stratification system, primarily governs the mainstream population. This caste system divides society into distinct hierarchical castes, including Brahmins (priests and scholars), Kshatriyas (warriors and rulers), Vaishyas (merchants and traders), and Shudras (peasants and labourers) [1, 2]. The caste system, which is determined by birth and restricts social mobility, has perpetuated discrimination and exclusion of lower castes, particularly the Shudras and Dalits, for centuries [3,4,5]. This, in turn, has resulted in socioeconomic disadvantages, limited access to education and employment opportunities, and limited political representation for these communities [3,4,5,6,7,8].

The mainstream Indian population is currently divided into Scheduled Castes (SCs), Other Backward Classes (OBCs), and Others. Those at the bottom of the social hierarchy, who have been subjected to centuries of discrimination, oppression, and abuse from those higher up in the hierarchy, are known as Scheduled Castes [6, 9, 10]. Other Backward Classes (OBCs) are socioeconomically and educationally disadvantaged communities, but their position in the social hierarchy is slightly higher than SCs. The remaining caste groups, which form the hierarchy’s top order, are grouped into a residual category called ‘Others’ [6, 8,9,10,11].

The indigenous population of India, primarily composed of tribal communities, is officially referred to as Scheduled Tribes (STs). Their categorisation is based on their unique cultural practices and geographical isolation rather than their placement in the caste hierarchy [12]. STs continue to be one of India’s most marginalised and disadvantaged communities, having faced several social, economic, and political challenges throughout history [2, 10, 11, 13]. SCs and STs comprise approximately 25% of India’s population, according to the 2011 Census of India [14]. Thus, the entire population of India is officially divided into four social groups: SC, ST, OBC, and Other.

The lasting impacts of past discrimination, restricted access to resources and opportunities, and current socioeconomic and economic disparities are reflected in the socioeconomic, demographic, and health outcomes of SC/ST communities [15]. SC/ST population frequently experience higher rates of preventable diseases, lower life expectancy, and higher maternal and infant mortality rates than other population groups. [16]. For instance, life expectancy at birth demonstrates a significant disparity across social groups, with SCs having the lowest life expectancy of 63.1 years and Others having the highest life expectancy of 68 years [17]. Additionally, SC/ST women are more likely to experience maternal morbidity and mortality than women from other social groups [16]. These maternal deaths are largely preventable if adequate and timely antenatal, delivery, and postpartum care is provided to mothers.

Antenatal care (ANC) is an essential aspect of maternal healthcare as it enables providers to identify and manage potential risks to the mother and foetus. It also offers an opportunity for women to receive information on healthy pregnancy practices and facilitates the early detection and treatment of pregnancy-related health issues [2, 18,19,20]. However, there is a debate about the optimal number of ANC visits for a pregnant woman. The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s, and Adolescents’ Health (2016–2030) Monitoring Framework recommends a minimum of four ANC visits [21], while the World Health Organization (WHO) suggests at least eight visits to lower perinatal mortality and enhance the quality of care for women [22]. Generally, a woman is considered to have received “full” ANC if she has had four or more ANC visits, at least two tetanus toxoid (TT) injections, and 100 iron-folic acids (IFA) tablets or an equivalent amount of IFA syrup during her pregnancy. While this definition is not exhaustive, it is widely recognised and utilised [2, 18, 23,24,25,26,27]

Despite the availability of publicly-funded antenatal care services in India, the utilisation of these services among pregnant women remains dismally low. Notably, a nationwide cross-sectional survey conducted in 2015–16 found that only 21% of pregnant women received the recommended full antenatal care [28]. Despite significant improvements in maternal health outcomes in India in the last thirty years, certain states and subgroups of the population still seem to be off track in meeting the Sustainable Development Goal of reducing maternal mortality to below 70 by 2030 [29]. To tackle this pressing public health challenge, it is imperative to identify pregnant women at risk of missing full antenatal care and discern the underlying factors contributing to this issue. This critical information can then be leveraged to develop targeted and effective public health interventions to improve maternal health and reduce maternal mortality.

The literature indicates that the low utilisation of maternal healthcare services is a multifaceted issue influenced by various factors [18, 20, 23, 27]. These include limited access to healthcare facilities, particularly in rural areas, poverty, and low income, as well as inadequate awareness regarding maternal healthcare, including the significance of prenatal care and the potential risks associated with childbirth [30, 31]. Additionally, the lack of female empowerment and decision-making authority can adversely impact maternal healthcare utilisation [32]. Furthermore, cultural beliefs, attitudes, social stigma, and discrimination have been found to be influential factors [33]. Socioeconomic and educational status are also significant contributors to maternal healthcare utilisation. Studies show that women from higher socioeconomic backgrounds and those with higher education levels are more likely to access maternal healthcare services [19, 20, 27]. Moreover, limited transportation availability poses a challenge, particularly in geographically challenging areas, hindering access to care services. On the supply side, inadequate infrastructure and a shortage of trained staff can lead to suboptimal care and may discourage women from seeking care [30, 31, 34].

Adolescence is a critical period of physical, social, and emotional development, and pregnancy during this time can profoundly impact a young woman’s health and future. In addition, adolescent pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality, making access to quality ANC services particularly important for this population [26]. However, adolescent girls are often subjected to discrimination and marginalisation in several societies, making accessing health services, including ANC, challenging [35]. This challenge can be further compounded by factors such as poverty, limited education, and lack of access to transportation, which can act as barriers to seeking care [35,36,37]. Furthermore, cultural norms and beliefs may discourage adolescent girls from seeking care, or they may feel embarrassed or ashamed to attend ANC visits [38,39,40].

Given the paramount importance of antenatal care (ANC) in mitigating the health risks associated with adolescent pregnancy, it is imperative to investigate the factors that affect the utilisation of full ANC services among adolescent women. This is particularly critical for SC/ST women, who have historically faced disadvantages in various aspects of life. However, despite the abundant literature on the utilisation of full ANC services in India, no studies have specifically examined the utilisation of these services among adolescent SC/ST women. Thus, this study aims to address this gap by investigating the utilisation of full ANC services among adolescent SC/ST women in India, using nationally representative data from the National Family Health Survey-4.

Data and methods

Data source

The data for this study came from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), the fourth round of a large-scale, multi-round survey covering the whole country. It was conducted in 2015 and 2016. The NFHS is India’s version of the DHS and provides reliable estimates of national, state, and regional indicators, including maternal and child health care services. NFHS-4 was approved by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare and conducted by the International Institute of Population Sciences (IIPS), Mumbai [41]. NFHS-4 employed a systematic multistage stratified sampling design. The survey’s sampling methodology is described in detail in the NFHS-4 national report.

The survey conducted face-to-face interviews with 699,686 ever-married mothers aged 15–49 from 601,509 sampled households in India, yielding an overall response rate of 96.7%. Of these women, 17.84% (124,878) belonged to the 15–19 age group. After excluding 118,979 of these women (95.27%) who had not given birth in the five years preceding the survey, the study obtained a sample of 5,899 adolescent mothers, of which 43% (2,549) belonged to the SC and ST social groups. Furthermore, 3.7% (95) of the mothers were removed from the sample because they were not currently married. Therefore, the analysis in this paper is based on a sample of 2,454 SC/ST adolescent mothers (see Fig. 1).

Dependent variable

In this study, the dependent variable used was “full ANC,” which comprised of three main components: having at least four ANC visits, receiving at least two tetanus toxoid (TT) injections, and consuming iron-folic acid (IFA) tablets or an equivalent amount of IFA syrup for 100 days during pregnancy. A pregnant mother was considered to have received “full ANC” only if she met all three criteria [42]. The “full ANC” indicator is recommended by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, the Government of India, and the World Health Organization [43], and is also used in the National Family Health Survey’s national and state level reports.

Independent variables

We considered a range of socioeconomic and demographic predictors such as woman’s education, mothers’ occupation, religion, exposure to mass media, meeting with frontline worker, economic status, meeting with ASHA worker, parity, region of residence, and place of residence. The choice of these variables is guided by existing literature available from low- and middle-income developing countries on antenatal care utilisation [23, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. The model of the utilisation of maternal health services used in this analysis is based on the previous studies and models. (See Appendix A Table).

Statistical analysis

We used both bivariate and multivariate analysis in order to identify factors associated with full ANC use among SC/ST adolescent mothers in India. Contingency table was used to understand how the utilisation of full ANC varied by socioeconomic and demographic characteristics of SC/ST adolescent mothers. Binary logistic regression was used to understand the net effect of predictor variables on the use of full ANC. We chose binary logistic regression because our response variable was dichotomous (i.e., binary) in nature. Before the final regression model was run with all independent variables included, we evaluated the relationship between the dependent variable and each individual independent variable through the use of a logistic regression. The odds ratios obtained from this analysis were referred to as “unadjusted” odds ratios since the models did not control for other variables. Those independent variables which did not turn out to be statistically significant were not included in the final regression model. Those variables that were found to have a statistically significant relationship were included in the final regression model and the odds ratios obtained from this analysis were referred to as “adjusted” odds ratios. These adjusted odds ratios were then utilised to conclude the effect of the independent variables on the dependent variable. The likelihood of multicollinearity impacting the results of our regression analysis was assessed using the variance inflation factor (VIF). The VIF is a measure of how much the variance of a regression coefficient is increased due to multicollinearity within the model. A general guideline suggests that VIF values above four warrant further examination, while VIF values exceeding ten indicate significant multicollinearity that requires correction. However, none of the VIF values for our regression model were above four indicating that multicollinearity was not a concern [54]. The results of the logistic regression models were presented in the form of odds ratios with p-values and 95% confidence intervals (CI). To accommodate the intricate survey design of NFHS-5, we incorporated the ‘svyset’ command in Stata16 [55].

Results

Altogether, the sample for the entire country consisted of 5899 adolescent mothers, with approximately 43% (2549) belonging to the SC/ST social categories. This figure was slightly higher than the representation of SC/ST in the overall population, which is estimated to be around 25%. The increased fertility among SC/ST adolescent women as compared to non-SC/ST women may account for this discrepancy. Table 1 provides details regarding the distribution of the sampled SC/ST adolescent mothers based on their background characteristics.

Utilisation of full ANC and different components of full ANC

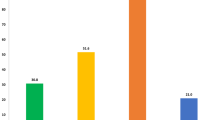

Figure 2 shows that the utilisation of full ANC among Indian adolescent SC/ST mothers was inadequate, with only about 18% utilising the full ANC. Among the three components of full ANC, the coverage of two or more TT injections was relatively high, with 83% of adolescent SC/ST mothers reporting to have received them. In contrast, the utilisation of other two key components of full ANC was found to be low, with only 46% of adolescent SC/ST mothers having made four or more ANC visits, and only 28% consuming the recommended number of IFA tablets or equivalent amount of IFA syrup.

Differentials in the utilisation of full antenatal care (ANC)

Table 2 displays the proportion of adolescent SC/ST mothers who reported receiving full ANC, categorised by their background characteristics. The results reveal significant discrepancies in full ANC utilisation across diverse categories of socioeconomic status, religion, region of residence, and maternal education. For instance, mothers in the poorest quintile were far less likely to receive full ANC, with only 10% reporting utilisation, compared to their counterparts in the richest quintile, where 40% reported utilisation. Furthermore, there was a notable gap in full ANC utilisation between Hindu and Muslim women, as only 17% of Hindu mothers received full ANC in comparison to a meagre 2% of Muslim mothers. The difference was most marked between adolescent SC/ST mothers residing in the central region (coverage of full ANC at 4%) versus those residing in the southern region (coverage of full ANC at 40%). Lastly, mothers who had met with a frontline worker reported almost twice the coverage of full ANC (21%) compared to those who had not (12%). Full ANC utilisation showed minor variation across other variables.

Determinants of full antenatal care (ANC) utilisation

A multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the individual influence of various factors on SBI. The outcomes were presented as odds ratios. The unadjusted odds ratios showed that the mother’s age and parity were not significant predictors and were therefore not included in the final (adjusted) regression model (see Table 3). The final model revealed the wealth index, religion, place of residence, and interaction with a frontline worker were the statistically significant factors that determine the utilisation of full ANC services among adolescent SC and ST mothers, while mother’s education and mass media exposure turned insignificant (see Table 4).

Mothers from the richest wealth quintile were more than five times (OR = 5.505, CI = 1.804–16.800) more likely to receive full ANC than those belonging to the poorest wealth quintile. Mothers who had met with a frontline worker were nearly two times more likely (OR = 1.821, CI = 1.241–2.670) to receive full ANC than mothers who had not met with a frontline worker. Muslim mothers were far less likely (OR = 0.143, CI = 0.044–0.459) to receive full ANC than their Hindu counterparts. Adolescent SC and ST mothers residing in the South had almost four times higher odds of receiving full ANC (OR = 3.575, CI = 1.917–6.664) compared to their counterparts in the North. On the other hand, those living in the Central region had lower odds of receiving full ANC (OR = 0.331, CI = 0.168–0.652).

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to examine the coverage of full ANC among SC/ST adolescent mothers and the factors associated with it. The study’s results indicate that the coverage of full utilisation of ANC services among adolescent mothers from these marginalised groups remains inadequate [56] The coverage of four or more ANC and sufficient intake of IFA tablets or syrup among the three components of full ANC was significantly lower than the coverage of TT injection. Several factors were found associated with the utilisation of full ANC services among SC/ST adolescent mothers. These included household wealth, religion, parity, region of residence, and interaction with frontline workers.

Among the three full ANC components, the uptake of IFA was considerably lower than other two components. Only 3 out of 10 mothers had adequate uptake of IFA supplementation. This situation exists even when the Government of India has been making efforts to improve IFA intake among mothers under the Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child plus Adolescent Health (RMNCH + A) program [57], Anaemia Mukt Bharat [58], and the National Iron + Initiative [59]. Previous research from Rajasthan and Odisha has shown that adverse effects, unpleasant smell and taste, forgetfulness, and a lack of information about IFA from frontline health workers restrict the usage of IFA among pregnant women [60]. In addition to these demand-side obstacles, supply-side obstacles, such as stock-outs, hinder access to IFA supplements [61]. There is an immediate need to rethink the strategy to boost the use of IFA supplementation among adolescent SC/ST mothers.

Furthermore, the current study indicates that religion plays a significant role in determining the utilisation of full ANC services among adolescent SC/ST mothers, which is consistent with earlier research conducted in India [31, 62]. Specifically, the study found that Muslim women were less likely to utilise full ANC services in comparison to their Hindu counterparts. It is likely that religious beliefs and traditional practices specific to Muslim women may contribute to their lower utilisation of antenatal care services. Additionally, the lower levels of autonomy and awareness among adolescent Muslim and SC/ST women may be associated with their inadequate utilisation of full ANC services [12, 63, 64]. Adolescent SC/ST mothers belonging to the Muslim community may encounter various hurdles such as cultural stigma, discrimination, and socioeconomic constraints that impede their access to adequate maternal health care services. These findings underscore the significance of addressing religious and cultural barriers that obstruct Muslim women’s ability to utilise full ANC services. To overcome these challenges, there is a need for culturally sensitive and inclusive maternal health programs that cater to the specific needs of adolescent Muslim SC/ST women.

The study findings indicate a significant discrepancy in the utilisation of full antenatal care services among adolescent SC/ST mothers from distinct economic backgrounds. Mothers from wealthier households are more likely to receive full ANC as compared to those from poor households. This disparity between the rich and poor is consistent with earlier research studies conducted in India [25, 56, 65,66,67,68] and elsewhere [32, 69, 70]. Adolescent SC/ST mothers from poor households face numerous obstacles in accessing full antenatal care services. They are often less educated, unemployed, and socially isolated, which makes it challenging for them to avail of such care. Due to their limited resources, they also tend to overlook the significance of maternal health care services, including full ANC. As a result, they prioritise spending their limited resources on daily basic needs over maternal health care. This is particularly true for poor adolescent SC/ST women, who are often uneducated, unemployed, and detached from social networks, thus making them more challenging to reach with full ANC [71, 72].

This study those women who had met with a frontline worker were more likely to utilise full ANC services. This is in line with many previous studies [31, 51]. Auxiliary Nurse Midwife (ANM), Accredited Social Health Activist (ASHA), and Anganwadi workers are key in improving maternal healthcare utilisation [31]. These frontline providers offer health education, counselling, and services, especially in rural areas with limited access to healthcare. ANMs and ASHAs are trained professionals responsible for prenatal and postpartum care, regular check-ups, and essential maternal health services. Anganwadi workers, serving in rural communities, offer maternal and child health services, nutrition, and health education, raising awareness about maternal health issues and encouraging proper antenatal care [9, 26]. These frontline workers help improve maternal healthcare utilisation, reduce maternal and infant mortality rates, and ensure quality maternal healthcare for marginalised mothers [31, 51]. The low coverage of full ANC among SC/ST mothers calls for a rethinking of the strategies employed by ANM, ASHA, and Anganwadi workers to increase utilisation of full ANC.

This study also highlights disparities in the full ANC coverage among adolescent SC/ST mothers in different regions. Adolescent mothers from the South region are more likely to receive full ANC, which aligns with findings from previous studies conducted in India [23, 67, 73, 74]. The reason for this disparity may be due to various factors such as differences in maternal healthcare infrastructure, healthcare access, awareness of maternal health issues, cultural beliefs, and health-seeking behaviours among the mothers in the southern states compared to other regions of India. Further research is needed to determine the specific factors that contribute to this disparity and how it can be addressed to improve maternal healthcare access and utilisation of full antenatal care services across India.

This study has several limitations that must be taken into consideration when interpreting the results. Firstly, certain important variables were not incorporated into the analysis due to a high number of missing values. Secondly, the study only analysed the association between explanatory factors and full utilisation of ANC services and did not examine any causal relationships. Additionally, the decision-making process of both spouses regarding the use of healthcare services was not included due to the lack of available data in the study. The sample size of this study did not allow to examine the utilisation of full ANC among SC/ST women at state and district level which could be useful for policymakers. Lastly, it should be noted that conclusions about causality cannot be drawn from this study as the data used is cross-section in nature. The study relies solely on self-reported data from the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) and does not use additional objective sources to validate the information provided. While self-reported data raises some concerns, it is less likely to be biased in maternal healthcare-related events than in other sensitive topics like sexual behaviour.

Conclusion

Despite various government initiatives, the utilisation of full ANC among adolescent SC/ST mothers remains inadequate and leaves much to be desired. This population of mothers has been largely neglected in maternal health policies and programs, despite being one of the most vulnerable groups of reproductive age mothers. The results of the study demonstrate that socioeconomic factors, including household wealth, religion, place of residence, and interaction with frontline workers, have an impact on the utilisation of full ANC among adolescent SC/ST mothers. These findings emphasise the importance of addressing social determinants of health to enhance full ANC utilisation among adolescent SC/ST mothers. Additionally, the critical role of frontline workers such as ANM, ASHA, and Anganwadi worker in improving full ANC coverage must be recognised. Furthermore, targeted interventions are needed to improve full ANC utilisation among specific subgroups of adolescent SC/ST mothers in India.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset analysed during the current study is available in the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) repository, https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm, and can be obtained for free by sending an online request. Codes used in the analysis can be made available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- NFHS:

-

National Family Health Survey

- OR:

-

Odds Ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence Interval

- SC:

-

Scheduled Caste

- ST:

-

Scheduled Tribe

- ANC:

-

Antenatal Care

- MMR:

-

Maternal Mortality Ratio

- RCH:

-

Reproductive and Child Health

References

Ganapathy K. Distribution of neurologists and neurosurgeons in India and its relevance to the adoption of telemedicine. Neurol India. 2015;63:142.

Kumar A, Singh A. Explaining the gap in the use of maternal healthcare services between social groups in India. J Public Heal. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdv142.

Vaid D. Caste in contemporary India: flexibility and persistence. Annu Rev Sociol. 2014;40:391–410.

Dumont L. Homo Hierachicus- The caste system and its implications. 1980. p. 12.

Desai S, Dubey A. Caste in the 21st century: competing narratives. Econ Polit Wkly. 2012;46:40–9.

Saroha E, Altarac M, Sibley LM. Caste and maternal health care service use among Rural Hindu Women in Maitha, Uttar Pradesh. India J Midwifery Womens Health. 2008;53:e41–7.

Subramanian S, Ackerson L, Subramanyam M, Sivaramakrishnan K. Health inequalities in India: the axes of stratification. Brown J World Aff. 2008;14:127–38.

Subramanian SV, Nandy S, Irving M, Gordon D, Lambert H, Smith GD. The mortality divide in India: the differential contributions of gender, caste, and standard of living across the life course. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:818–25.

Patel P, Das M, Das U. The perceptions, health-seeking behaviours and access of Scheduled Caste women to maternal health services in Bihar. India Reprod Health Matters. 2018;26:114–25.

Bango M, Ghosh S. Social and Regional disparities in utilization of maternal and child healthcare services in India: a study of the post-national health mission period. Front Pediatr. 2022;10:1–11.

Baru R, Acharya A, Acharya S, Kumar AKS, Nagaraj K. Inequities in access to health services in India: Caste, class and region. Econ Polit Wkly. 2010;45(38):49-58.

Nayar KR. Social exclusion, caste & health: a review based on the social determinants framework. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:355–63.

Uddin J, Acharya S, Valles J, Baker EH, Keith VM. Caste differences in hypertension among Women in India: diminishing health returns to socioeconomic status for lower caste groups. J Racial Ethn Heal Disparities. 2020;7:987–95.

National Commission on Population. Population projections for India and states 2011–2036. New Delhi: Government of India; 2019.

Thapa R, van Teijlingen E, Regmi PR, Heaslip V. Caste exclusion and health discrimination in South Asia: a systematic review. Asia-Pacific J Public Heal. 2021;33:828–38.

Radkar A, Parasuraman S. Maternal deaths in India: an exploration. Econ Polit Wkly. 2007;42:3259–63.

Kumari M, Mohanty SK. Caste, religion and regional differentials in life expectancy at birth in India: cross-sectional estimates from recent National Family Health Survey. BMJ Open. 2020;10:1–10.

Singh A. Supply-side barriers to maternal health care utilization at health sub-centres in India. PeerJ. 2016;4:1–23.

Jat TR, Ng N, San Sebastian M. Factors affecting the use of maternal health services in Madhya Pradesh state of India: a multilevel analysis. Int J Equity Health. 2011;10:1–11.

Hamal M, Hamal M, Hamal M, Dieleman M, Dieleman M, De Brouwere V, et al. Social determinants of maternal health: a scoping review of factors influencing maternal mortality and maternal health service use in India. Public Health Rev. 2020;41:1–24.

World Health Organization. The Global Strategy for Women’s, Children’s and Adolescents’ Health. 2015.

Zainur RZ, Loh KY, Fammed M. Postpartum morbidity - What We Can Do. Med J Malaysia. 2006;61:651–7.

Navaneethama K, Dharmalingam A. Utilization of maternal health care services in Southern India. Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:1849–69.

Singh A, Mukherjee S, Chandra R. Inter-district variation in socio-economic inequalities in maternal healthcare utilisation in rural Assam, 2007–08. J North East India Stud. 2012;2:94–103.

Pathak PK, Singh A, Subramanian SV. Economic inequalities in maternal health care: prenatal care and skilled birth attendance in India, 1992–2006. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13593.

Singh A, Kumar A, Pranjali P. Utilization of maternal healthcare among adolescent mothers in urban India: evidence from DLHS-3. PeerJ. 2014;2:e592.

Singh R, Neogi SB, Hazra A, Irani L, Ruducha J, Ahmad D, et al. Utilization of maternal health services and its determinants: a cross-sectional study among women in rural Uttar Pradesh. India J Health Popul Nutr. 2019;38:13.

International Institute for Population Sciences (IIPS) and ICF. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4), 2015–16. India: IIPS; 2017.

Meh C, Sharma A, Ram U, Fadel S, Correa N, Snelgrove JW, et al. Trends in maternal mortality in India over two decades in nationally representative surveys. BJOG. 2022;129:550.

Kumar S, Dansereau E, World B, Adamson P, Krupp K, Niranjankumar B, et al. Supply-side barriers to maternity-care in India: a facility-based analysis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e103927.

Singh A. Supply-side barriers to maternal health care utilization at health sub-centers in India. PeerJ. 2016. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2675.

Ahmed S, Creanga AA, Gillespie DG, Tsui AO. Economic status, education and empowerment: implications for maternal health service utilization in developing countries. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11190.

Alderdice F, Kelly L. Stigma and maternity care. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 2019;37:105–7.

Varghese JS, Swaminathan S, Kurpad AV, Thomas T. Demand and supply factors of iron-folic acid supplementation and its association with anaemia in North Indian pregnant women. PLoS One. 2019;14:e0210634.

Erasmus MO, Knight L, Dutton J. Barriers to accessing maternal health care amongst pregnant adolescents in South Africa: a qualitative study. Int J Public Health. 2020;65:469–76.

Hokororo A, Kihunrwa AF, Kalluvya S, Changalucha J, Fitzgerald DW, Downs JA. Barriers to access reproductive health care for pregnant adolescent girls: a qualitative study in Tanzania. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:1291–7.

Nambile Cumber S, Atuhaire C, Namuli V, Bogren M, Elden H. Barriers and strategies needed to improve maternal health services among pregnant adolescents in Uganda: a qualitative study. Glob Health Action. 2022;15(1):2067397.

Honkavuo L. Women’s experiences of cultural and traditional health beliefs about pregnancy and childbirth in Zambia: an ethnographic study. Health Care Women Int. 2021;42:374–89.

Shahabuddin A, Nöstlinger C, Delvaux T, Sarker M, Delamou A, Bardají A, et al. Exploring maternal health care-seeking behavior of married adolescent girls in bangladesh: a social-ecological approach. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0169109.

Omer S, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. The influence of social and cultural practices on maternal mortality: a qualitative study from South Punjab. Pakistan Reprod Health. 2021;18:1–12.

International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) 2015–16 India. India: Mumbai; 2017.

UNICEF. Antenatal Care. UNICEF; 2021.

WHO. Guideline: daily iron and folic acid supplementation in pregnant Women. Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2012.

NC Saxena, N Chandhiok, BS Dhillon IK, Saxena NC, Chandhiok N, Dhillon BS KI. Determinants of antenatal care utilization inrural areas of India: A cross-sectional study of 28 districts. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2006;56:47–52.

Zuhair M, Roy RB. socioeconomic determinants of the utilization of antenatal care and child vaccination in India. Asia-Pacific J Public Heal. 2017;29:649–59.

Javali R, Wantamutte A, Mallapur M. Socio-demographic factors influencing utilization of Antenatal Health Care Services in a rural area - A cross sectional study. Int J Med Sci Public Heal. 2014;3:308–12.

Joshi C, Torvaldsen S, Hodgson R, Hayen A. Factors associated with the use and quality of antenatal care in Nepal: a population-based study using the demographic and health survey data. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14:1–11.

Kakati R, Barua K, Borah M. Factors associated with the utilization of antenatal care services in rural areas of Assam, India. Int J Community Med Public Heal. 2016;3:2799–805.

Kumar P, Gupta A. Determinants of Inter and Intra caste Differences in Utilization of Maternal Health Care Services in India: evidence from DLHS-3 survey. Int Res J Soc Sci. 2015;4:27–36.

Salam A, Siddiqui S. Socioeconomic inequalities in use of delivery care services in India. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2006;56:123–7.

Saxena NC, Chandhiok N, Dhillon BSKI. Determinants of antenatal care utilization inrural areas of India: a cross-sectional study of 28 districts. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2006;56:47–52.

Simkhada B, Teijlingen ER, Porter M, Simkhada P. Factors affecting the utilization of antenatal care in developing countries: Systematic review of the literature. J Adv Nurs. 2008;61(3):244-60.

Varma GR, Kusuma YS, Babu BV. Antenatal care service utilization in tribal and rural areas in a South Indian district: an evaluation through mixed methods approach. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2011;86:11–5.

Miles J. Tolerance and Variance Inflation Factor. In: Wiley StatsRef: Statistics Reference Online. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2014.

StataCorp LLC. Stata Statistical Software. 2019. p. 1–401.

Singh PK, Rai RK, Alagarajan M, Singh L. Determinants of maternity care services utilization among married adolescents in rural India. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31666.

Ministry of Health & Family Welfare. A Strategic Approach to Reporoductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child and Adolescent Health (RMNCH+A) in India. Government of India; 2013.

Bhatia PV, Sahoo DP, Parida SP. India steps ahead to curb anemia: Anemia Mukt Bharat. Indian J Community Health. 2018;30:312–6.

MoHFW. National Iron+ Initiative: Guidelines for control of Iron deficiency Anaemia. 2013.

Sedlander E, Long MW, Mohanty S, Munjral A, Bingenheimer JB, Yilma H, et al. Moving beyond individual barriers and identifying multi-level strategies to reduce anemia in Odisha India. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1–16.

Varghese JS, Swaminathan S, Kurpad AV, Thomas T. Demand and supply factors of iron-folic acid supplementation and its association with anaemia in North Indian pregnant women. PLoS One. 2019;14:1–13.

Singh A, Kumar A, Pranjali P. Utilization of maternal healthcare among adolescent mothers in urban India: evidence from DLHS-3. PeerJ. 2014. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.592.

Basant R. Social, economic and educational conditions of Indian muslims. In: Economic and Political Weekly. 2007. p. 828–32.

Mistry R, Galal O, Lu M. Women’s autonomy and pregnancy care in rural India: a contextual analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:926–33.

Mohanty SK, Pathak PK. Rich-Poor gap in utilization of reproductive and child health services in India, 19922005. J Biosoc Sci. 2009;41:381–98.

Kesterton AJ, Cleland J, Sloggett A, Ronsmans C. Institutional delivery in rural India: the relative importance of accessibility and economic status. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10:30.

Paul P, Chouhan P. Socio-demographic factors influencing utilization of maternal health care services in India. Clin Epidemiol Glob Heal. 2020;8:666–70.

Kumar G, Choudhary TS, Srivastava A, Upadhyay RP, Taneja S, Bahl R, et al. Utilisation, equity and determinants of full antenatal care in India: analysis from the National Family Health Survey 4. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:327.

Banke-Thomas OE, Banke-Thomas AO, Ameh CA. Factors influencing utilisation of maternal health services by adolescent mothers in Low-and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17:1–14.

Gebre E, Worku A, Bukola F. Inequities in maternal health services utilization in Ethiopia 2000–2016: magnitude, trends, and determinants. Reprod Health. 2018;15:1–9.

Rani M, Lule E. Exploring the socioeconomic dimension of adolescent reproductive health: a multicountry analysis. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30:110–7.

Rai RK, Tulchinsky TH. Addressing the sluggish progress in reducing maternal mortality in India. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27:NP1161-9.

Ogbo FA, Dhami MV, Ude EM, Senanayake P, Osuagwu UL, Awosemo AO, et al. Enablers and barriers to the utilization of antenatal care services in India. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:3152.

Barman B, Saha J, Chouhan P. Impact of education on the utilization of maternal health care services: an investigation from National Family Health Survey (2015–16) in India. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;108:104642.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) for providing the dataset for this study. We acknowledge the support provided by Banaras Hindu University’s Institute of Eminence (IoE) Seed Grant No. R/Dev/D/IoE/Equipment/Seed Grant-II/2022-23/48726.

Funding

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AS: conceptualization, design, data analysis, interpretation of data, visualization, supervision, writing – review and editing. VK: data analysis, interpretation of data, writing – original draft. HS, SC & SS: writing – review and editing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The present study used secondary data, which is available in the public domain. The dataset has no identifiable information about the survey participants.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Appendix Table A. Operational definitions and categorization of variables used in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Singh, A., Kumar, V., Singh, H. et al. Assessing the coverage of full antenatal care among adolescent mothers from scheduled tribe and scheduled caste communities in India. BMC Public Health 23, 798 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15656-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15656-1