Abstract

Background

This meta-analysis aimed to explore the epidemiological characteristics of alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) in China.

Methods

Studies published between January 2000 and January 2023 were searched from 3 databases in English and 3 databases in Chinese. DerSimonian-Laird’s random-effects model was adopted to calculate the pooled prevalence.

Results

A total of 21 studies were included. The pooled prevalence of ALD was 4.8% (95% CI, 3.6%-6.2%) in the general population, 9.3% (95% CI, 4.4%-16.0%) in males, and 2.0% (95% CI, 0.0%-6.7%) in females. The prevalence was the highest in western China (5.0% [95% CI, 3.3%-6.9%]) and the lowest in central China (4.4% [95% CI, 4.0%-4.8%]). The prevalence among people with different drinking histories (less than 5 years, 5 to 10 years, and over 10 years) was 0.9% (95% CI, 0.2%-1.9%), 4.6% (95% CI, 3.0%-6.5%), and 9.9% (95% CI, 6.5%-14.0%), respectively. The prevalence in 1999–2004 was 4.7% (95% CI, 3.0%-6.7%) and then changed from 4.3% (95% CI, 3.5%-5.3%) in 2005–2010 to 6.7% (95% CI, 5.3%-8.3%) in 2011–2016.

Conclusions

The prevalence of ALD in China has increased in recent decades, with population-related variations. Targeted public health strategies are needed, especially in high-risk groups, such as male with long-term alcohol drinking.

Trial registration

The registration number on PROSPERO is CRD42021269365.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) is a chronic liver disease related to long-term excessive drinking. ALD is often manifested as alcohol-related fatty liver in the early stage, which may progress to alcohol-related hepatitis, liver fibrosis, cirrhosis, and even liver cancer [1]. Among the annual two million deaths related to liver disease, 50% die from ALD [2]. According to epidemiological data, alcohol intake (volume or history) is closely associated with the risk of liver damage [3].

As reported by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2], the annual per capita alcohol consumption in China is 7.2 L, above the global level (6.4 L) and still on the rise (estimated to reach 8.1 L by 2025 for Chinese people aged 15 and above). Regional epidemiological surveys have shown an increase in the proportion of alcoholics in the general Chinese population, with the prevalence of ALD ranging from 0.50% to 8.55% in some provinces [2, 4,5,6]. The proportion of ALD in hospitalized patients with liver disease has doubled from 2002 to 2013 [7]. ALD has brought serious health hazards and economic burdens to individuals, families and society.

In China, ALD is diagnosed and treated according to the guidelines established by the Chinese Society of Hepatology [2]. Alcohol abstinence and nutritional supplementation are cornerstones in ALD management, sometimes supported by pharmacological interventions [2, 8, 9]. However, the efficacy and safety of some medications need further evaluation. Critical cases even need liver transplantation (LT). Considering the challenges in treating ALD, early prevention should be carried out based on a full understanding of its epidemiological characteristics.

In China, the prevalence of ALD has been analyzed at the regional level, but never at the national level [10]. Therefore, in this study, we meta-analyzed the epidemiological characteristics of ALD in China.

Methods

This meta-analysis was performed conforming to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11], and pre-registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) with a registration number of CRD42021269365.

Search strategy

We searched PubMed, Web of Science, Embase, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Wanfang, and Chinese Biomedicine Literature Database (CBM-SinoMed) for articles published from January 2000 to January 2023 and written in English or Chinese. The keywords included “alcoholic liver disease”, “alcohol liver disease”, “alcohol-related liver disease”, “alcoholic hepatitis”, “alcoholic cirrhosis”, “prevalence”, “epidemiology”, “China”, “Chinese mainland”, “Hong Kong”, “Taiwan”, and “Macao”. The searching strategy is described in Supplement A. We also examined the references in the included studies to enrich the data.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All observational studies were selected if they fulfilled all of the following inclusion criteria: (1) being original articles; (2) including Chinese populations; (3) providing original data on the prevalence of ALD; (4) describing the diagnostic criteria for ALD; (5) existing in a full text; (6) based on a general population rather than patients from one hospital. When duplicate studies were carried out based on the same population, the one with the richest data was selected. Studies were excluded if they: (1) were not published in English or Chinese; (2) were published at least 20 years before; (3) focused on specific groups, such as elderly people, teenagers, or a certain occupation.

After removing the duplicates, two researchers reviewed the titles, abstracts, and full texts of selected articles independently to determine those to be included. Any discrepancy between them was resolved by discussion.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers independently checked the risk of bias in included studies according to The Joanna Briggs Institute Prevalence Critical Appraisal Tool [12]. The possible bias was evaluated in nine domains, including sample frame, sampling method, sample size, study subjects and setting, data analysis, etc. The details can be found in Supplement B. Each item was rated as “yes”, “no”, “unclear” or “not applicable” according to information available in each study, with a maximum score of nine points. A third reviewer solved disagreements regarding the quality of studies between the two reviewers.

Data extraction

Data were extracted independently by two researchers. A consensus was reached for any discrepancy through discussion. We used a pre-determined data collection form to extract and record data in excel spreadsheets. The data were about author (s), time of publication, region, residence (urban/rural/mixed), time of study, sampling strategy, sample size, cases, age range, and sex ratio. For articles without providing the time of study, we replaced it with a date subtracting the time of publication by 2 years, based on the average interval between the dates of investigation and publication.

Statistical analysis

We utilized OpenMeta (Analyst) software and Stata (version 15.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX) to perform meta-analysis. Pooled prevalence of ALD and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were considered as the measures of effect. Due to the small prevalence of ALD in each study (0 < P < 0.2), the data were subjected to double arcsine transformation. Heterogeneity of the eligible studies was evaluated according to Cochrane Q and I2 statistics. A p-value less than 0.1 indicated heterogeneity, and I2 values of 25%, 50%, and 75% were considered to represent low, moderate, and high heterogeneity, respectively. A DerSimonian-Laird’s random-effects model was used for studies with significant heterogeneity; otherwise, a fixed-effects model was conducted. A sensitivity analysis was performed to remove studies at a high risk of bias. To detect the source of heterogeneity, subgroup analysis was conducted on sex, region, drinking duration and study year. The region was defined according to the proposal of the National Bureau of Statistics of China: (1) Northeastern China covers Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang; (2) Eastern China covers Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, Hainan, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau; (3) Western China covers Shaanxi, Sichuan, Yunnan, Guizhou, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, Gansu, Qinghai, Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region, Tibet Autonomous Region, Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region and Chongqing; (4) Central China covers Shanxi, Henan, Anhui, Hubei, Jiangxi and Hunan. We first used a funnel chart to visualize the bias, then Egger’s test and Begg’s test to evaluate the significance. The statistical significance was set at P = 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of studies selected

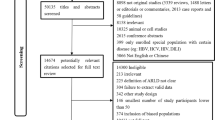

As shown in Fig. 1, we initially obtained 4099 results, and 112 were excluded as duplicates. After screening the abstracts and titles in these publications, we retained 86 articles. Then, 62 of them were excluded for incomplete texts, 3 for low-quality. Finally, 21 articles were included, including 6 articles published in English and 15 articles in Chinese.

Their characteristics are summarized in Table 1. The 21 articles were published between 2001 and 2022, of which 7 (33.3%) were published before 2010; 18 articles were conducted in urban–rural settings, 2 in urban regions and 1 in rural regions. In addition, we observed that the prevalence of ALD in both men and women was reported in 13 included articles. Moreover, the populations in these 21 articles were selected from 16 provinces in China. Given this wide coverage, we conducted a subgroup analysis according to four regions introduced by the National Bureau of Statistics of China. The quality of all included articles met the research requirement. The quality assessment is presented in Supplement B.

Pooled prevalence and stratified prevalence of ALD in China

The pooled prevalence of ALD in China was 4.8% (95% CI, 3.6%-6.2%), as shown in random-effects meta-analysis (Fig. 2).

The prevalence was analyzed in subgroups (Table 2) set according to the following categories: sex (male, female), study region (Northeastern, Eastern, Western, and Central China), drinking duration (below 5 years, 5–10 years, above 10 years), and time of study (1999–2004, 2005–2010, 2011–2016, 2017–2022). The higher prevalence of ALD was observed in men, West China, and people with more than 10 years of drinking history. Sex was closely associated with ALD prevalence (9.3% [95% CI, 4.4%-16.0%] in men vs. 2.0% [95% CI, 0.0%-6.7%] in women). The prevalence of ALD did not show a trend related to study time: 4.7% (95% CI, 3.0%-6.7%) in 1999–2004, 4.3% (95% CI, 3.5%-5.3%) in 2005–2010, 6.7% (95% CI, 5.3%-8.3%) in 2011–2016, and 2.4% in 2017–2022.

The prevalence of ALD varied evidently across four Chinese geographical regions (Table 2). The prevalence of ALD was the highest (5.0% [95% CI, 3.3%-6.9%]) in West China and the lowest (4.4% [95% CI, 4.0%-4.8%]) in Central China. The prevalence in East China was similar (5.0% [95% CI, 3.3%-6.9%]) to that in West China, while higher than that in Northeast China (4.8% [95% CI, 3.3%-6.5%]). More evident regional difference in ALD prevalence was seen between provinces of China (Fig. 3).

Also noticed in Table 2, the prevalence of ALD was higher in the subgroup with a longer drinking history than in the subgroup with a shorter drinking history. The prevalence of ALD in the subgroups with a drinking history of less than 5 years, 5–10 years, and more than 10 years was 0.9% (95% CI, 0.2%-1.9%), 4.6% (95% CI, 3.0%-6.5%), and 9.9% (95% CI, 6.5%-14.0%), respectively.

Analysis of heterogeneity and publication bias

Significant overall heterogeneity was noted in the included studies (P < 0.001, I2 = 99.30%). Therefore, we conducted a subgroup analysis, and unfortunately observed that the heterogeneity was not reduced in most subgroups. The sensitivity analysis showed that the pooled prevalence of ALD varied from 4.7% (95% CI, 3.5%-6.0%) to 5.1% (95% CI, 4.3%-5.9%) as each study was serially excluded, and no single study had a substantial influence on the pooled prevalence (Supplement C). Despite the apparent asymmetry of the funnel plot (Supplement D), no significant publication bias was identified by the Begg’s test (P = 0.365) with double arcsine transformation. However, Egger’s test revealed a significant publication bias (P < 0.001) (Supplement D).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis comprehensively described the prevalence of ALD in China based on data published from 2001 to 2022. We analyzed 21 epidemiological surveys covering 16 provincial regions in China. The pooled prevalence of ALD in China was 4.8% (95%CI, 3.6%-6.2%), which is consistent with that reported by authoritative institutions (range 2.3% to 6.1%, median 4.5%) [4]. Previous studies have shown that the prevalence in European countries was estimated at 6%, which is comparable to our finding [5, 34]. Furthermore, the prevalence of ALD in China is obviously higher than that in Japan (1.56% to 2.34%) [34] and South Korea (about 1.7%) [35].

Alcohol consumption pattern has undergone continuous change around the world [36]. China has become a country with the highest per-capita consumption of pure alcohol [5]. The proportion of regular drinkers among Chinese adults rose from 27.0% in 2000 to 66.2% in 2015, and the proportion of heavy drinkers rose from 0.21% in 1982 to 14.8% in 2000 [5]. In the present study, the prevalence of ALD in 2011–2016 (6.7%) was higher than that in 1999–2004 (4.7%) and 2005–2010 (4.3%), with an upward trend similar to that of proportion of drinkers. Interestingly, the ALD prevalence in 2017–2022 was only 2.4%, which was markedly lower than that in other subgroups. The combined prevalence in this subgroup may be associated with the small number of included studies. Besides, this result cannot be explained by the rise of alcohol desire and consumption in the Chinese population during the COVID-19 epidemic [37,38,39]. Studies have shown that during the COVID-19 epidemic, some individuals relieve mental stress and negative emotions through drinking alcohol, which may lead to or exacerbate problems such as alcohol abuse or dependence, further impairing their physical and mental health [40, 41]. Therefore, the impact of the epidemic on the prevalence of ALD deserves concern. However, investigations of ALD in China during the epidemic are still sporadic. It is important to note that two studies included in this subgroup were conducted in 2017–2020 and 2018–2020, and the detailed data in different years were not provided, so it is not rigorous to equate this prevalence to that of ALD during the COVID-19 epidemic. Considering the delay in the occurrence of ALD induced by drinking behavior [1], the impact of epidemic on ALD cannot be reflected by its prevalence. In the future, we hope that more studies on the epidemiological characteristics of ALD patients in the post-epidemic era will fill this gap. Meanwhile, previous studies have shown that drinking history is a risk factor for ALD [6, 42], which is supported by our research results: the prevalence of those with a drinking history of more than 10 years was notably higher than those with a drinking history of less than 5 years.

The prevalence of ALD varied prominently across geological regions in China. The pooled prevalence in West China was 5.0%, higher than the overall prevalence and that in Central China. There is a lack of studies on the association between geographical region and ALD in China, but a recent study [43] has pointed out that liver function indicators, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), is related to geographical factors. In the above study, the ALT level showed a spatial trend: high in the west and low in the east; high in the north and low in the south. Considering that ALD can increase laboratory ALT [44], we speculate that the prevalence of ALD may be influenced by geographical factors, but this requires the verification in more studies. Besides, the alcohol drinking habits across China probably also contribute to the region-related difference in ALD prevalence.

Another major finding of this study is that the prevalence of ALD was remarkably different between men (9.3%) and women (2.0%) in China. Numerous studies [45,46,47,48,49] have shown that men drink much more alcohol than women in China and many other countries [35, 50, 51], which can explain the sex-related difference in ALD prevalence. Actually, the alcohol consumption and ALD prevalence have both increased among women in recent years. As reported by the WHO, the proportion of female drinkers in the Western Pacific Region has gradually increased from 39.3% in 2000 to 40.7% in 2016, with an obvious upward trend [46]. Besides, a study [52] based on the Global Burden of Disease database states that from 2000 to 2017, the sex-related difference in ALD prevalence has become less prominent in the Nordic countries. Few studies have been conducted to analyze alcohol consumption and alcohol-related liver disease in Chinese women; thus, the gender-related trends in ALD prevalence over time should be further explored.

To date, this is the first meta-analysis to describe the total prevalence of ALD in China. Besides, we strictly controlled the quality of included articles. Moreover, double arcsine transformation of data was conducted before implementing robust statistical methods, thereby improving the reliability of the results [53].

Several limitations also exist. First, the results of the study are highly heterogeneous, limited by the nature of the meta-analysis of single-group rates. We had already attempted to avoid the potential publication bias in study screening, quality evaluation and data processing. Sensitivity analysis allowed us to obtain more stable results. We also adopted methods such as stratified analysis to reduce study heterogeneity. After subgroup analysis, the heterogeneity remains unexplained. In this study, various diagnostic methods for ALD may bring about high heterogeneity between included studies. Even if statistical heterogeneity may be excluded, the heterogeneity between clinical research cannot be eliminated. Second, we only collected data from some provinces of China, which may have a potential impact on the representativeness of the results. Third, most of included studies were carried out before 2010, and recent epidemiological studies lack.

Conclusions

This is the first meta-analysis to explore the total prevalence of ALD in China. The prevalence of ALD is relatively high and has increased slightly in China over the past few decades. More research is needed in the future to validate our results from this study.

Availability of data and materials

All datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current research are included in this article and its supplementary information file.

Abbreviations

- ALD:

-

Alcohol-related liver disease

- CNKI:

-

Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure

- CBM-SinoMed:

-

Chinese Biomedicine Literature Database

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- LT:

-

Liver transplantation

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

References

References used in the meta-analysis are marked with an asterisk next to them.

Fatty Liver and Alcoholic Liver Disease Study Group of the Chinese Liver Disease Association. Guidelines of prevention and treatment for alcoholic liver disease: a 2018 update. Chin J Hepatol. 2018;26(03):188–94.

WHO. Global status report on alcohol and health 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/274603. Accessed 10 Feb, 2021.

Rehm J, Taylor B, Mohapatra S, Irving H, Baliunas D, Patra J, et al. Alcohol as a risk factor for liver cirrhosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2010;29(4):437–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00153.x.

Fan JG. Epidemiology of alcoholic and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in China. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl 1):11–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12036.

Xiao J, Wang F, Wong NK, He J, Zhang R, Sun R, et al. Global liver disease burdens and research trends: analysis from a Chinese perspective. J Hepatol. 2019;71(1):212–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhep.2019.03.004.

Yan L, Lin S. Guideline for primary care of alcoholic liver disease (2019). Journal of Clinical Hepatology. 2021;37(01):36–40.

Huang A, Chang B, Sun Y, Lin H, Li B, Teng G, et al. Disease spectrum of alcoholic liver disease in Beijing 302 Hospital from 2002 to 2013: a large tertiary referral hospital experience from 7422 patients. Medicine. 2017;96(7):e6163. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000006163.

Chuanfeng L, Yunfeng P, Xiang Q. Current treatment of alcoholic liver disease. J Clin Hepatol. 2003;06:333–4.

Guotao L, Yucui Z, Tao Z, Jing W, Tao Y, Wei L, et al. Advances in research of alcoholic liver disease. World Chin J Digestol. 2017;25(15):1382–8.

Fatty Liver and Alcoholic Liver Disease Study Group of the Chinese Liver Disease Association. Guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of alcoholic liver disease. Chin J Liver Dis (Electronic Version). 2010;2(04):49–53.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2021;372:n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and cumulative incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–53. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054.

* Weixing C. Molecular Epidemiological Survey and Mechanism Study on Alcoholic Liver Disease [PhD dissertation]: Zhejiang University; 2001.

* Jinglian W, Linyan F, Xueyan Q. Prevalence of alcoholic liver disease in some residents of Daur nationality. Chin J Gen Pract. 2003;01:55–6.

* Shengqi W, Junjie W, Jing W. The prevalence survey of liver diseases induced by alcohol in personnel left the country in Henan port. Port Health Control. 2003;04:12–3.

* Youming L, Weixing C, Chaohui Y, Min Y, Youshi L, Genyun X, et al. An epidemiological survey of alcoholic liver disease in Zhejiang province. Chin J Hepatol. 2003;11:9–11.

* Xiaolan L, Jinyan L, Ming T, Ping Z, Hongli Z, Xiaodong Z, et al. Analysis of risk factors for alcoholic liver diseases. Chin J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;02:172–4.

* Shuiqi D, Shunlin H, Xuehong Z, Youjun Y, Meilian T, Changgeng Y. Epidemiological analysis of alcoholic liver disease in Hunan Province. Chin J Integr Tradit West Med Liver Dis. 2005;02:105–6.

* Zhou YJ, Li YY, Nie YQ, Ma JX, Lu LG, Shi SL, et al. Prevalence of fatty liver disease and its risk factors in the population of South China. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(47):6419–24. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v13.i47.6419.

* Jie S. The Status of Epidemiological Investigation and Analysis of Relevant Factors about Drinking and Alcoholic Liver Disease in DeHui City [PhD dissertation]: Jilin University; 2008.

* Lei C, Yang H, Li Z, Xiaoqian Z, Xu Y. Epidemiological investigation of alcoholic liver disease in adult physical examination population in Guiyang. Guizhou Med J. 2010;34(07):645–7.

* Shilin C, Xiaodan M, Bingyuan W, Guoqing X. An epidemiologic survey of alcoholic liver disease in some cities of Liaoning Province. J Clin Hepatology. 2010;13(06):428–30+35.

* Jinghui Y, Qiudong Z, Pengfen X, Dongmei H, Lixian Y, Yanping Z, et al. Investigation of alcoholic liver disease in ethnic groups of Yuanjiang county in Yunnan. Chinese Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2011;20(12):1137–9.

* Xiaodong S, Qi W, Shumei H, Yuchun T, Jie S, Junqi N. Epidemiology and analysis on risk factors of non-infectious chronic diseases in adults in northeast China. Journal of Jilin University(Medicine Edition). 2011;37(02):379–84.

* Yan J, Xie W, Ou WN, Zhao H, Wang SY, Wang JH, et al. Epidemiological survey and risk factor analysis of fatty liver disease of adult residents, Beijing. China Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology. 2013;28(10):1654–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgh.12290.

* Wang H, Ma L, Yin Q, Zhang X, Zhang C. Prevalence of alcoholic liver disease and its association with socioeconomic status in north-eastern China. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(4):1035–41.

* Yan H, Lu X, Gao Y, Luo J. Epidemiological investigation of fatty liver disease in Northwest China. Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi. 2015;23(8):622–7. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1007-3418.2015.08.013.

* Huan S, Hao X, Sun X, Ren Q, Zhu W. Prevalence and risk factors of fatty liver disease in urban adult residents of qingdao: An epidemiological survey. 2016.

* Baima KZ, Ouzhu LB, YZ C. Prevalence and risk factors of alcoholic liver disease among Tibetan native adults in Lhasa. Chin J Public Health. 2016;32(03):295–8.

* Qiannan L, Jianbo C, Yanxia B, Yan W, Jianhong B, Guangrong D. An epidemiological survey of alcoholic liver disease among staff of Yanchang Oilfield. J Clin Hepatol. 2017;33(09):1769–73.

* Huang C, Lv XW, Xu T, Ni MM, Xia JL, Cai SP, et al. Alcohol use in Hefei in relation to alcoholic liver disease: a multivariate logistic regression analysis. Alcohol (Fayetteville, NY). 2018;71:1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.alcohol.2017.08.001.

* Wang H, Gao P, Chen W, Yuan Q, Lv M, Bai S, et al. A cross-sectional study of alcohol consumption and alcoholic liver disease in Beijing: based on 74,998 community residents. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):723. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-13175-z.

* Pi JT, Wang C, Zhang JM, Zhang ZW, Li B, Lu Y, et al. Epidemiologic investigation of alcohol consumption and alcoholic liver disease among residents in the Tongzhou District of Beijing. Chronic Pathematol J. 2022;23(05):712–6. https://doi.org/10.16440/J.CNKI.1674-8166.2022.05.20.

Wong T, Dang K, Ladhani S, Singal AK, Wong RJ. Prevalence of alcoholic fatty liver disease among adults in the United States, 2001–2016. JAMA. 2019;321(17):1723–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.2276.

Park SH, Kim CH, Kim DJ, Park JH, Kim TO, Yang SY, et al. Prevalence of alcoholic liver disease among Korean adults: results from the fourth Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2009. Subst Use Misuse. 2011;46(14):1755–62. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2011.620053.

Rumgay H, Shield K, Charvat H, Ferrari P, Sornpaisarn B, Obot I, et al. Global burden of cancer in 2020 attributable to alcohol consumption: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22(8):1071–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(21)00279-5.

Dong P, Yi JL, Wu F, Ni ZJ, Zhao KQ, Sun GQ, et al. The related factors of increased drinking desire and alcohol consumption among drinkers during the COVID-19 epidemic. Chinese Journal of Drug Dependence. 2021;30(01):38–44. https://doi.org/10.13936/j.cnki.cjdd1992.2021.01.008.

Hepatology TLG. Alcohol-related harm during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6(7):511. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-1253(21)00185-0.

Sun FW, Yang M. Drinking behavior and drinking-related problems among populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Chin J Drug Dependence. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3920.R.20221227.1347.001.html.

Becker HC. Influence of stress associated with chronic alcohol exposure on drinking. Neuropharmacology. 2017;122:115–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2017.04.028.

Hogarth L, Hardy L, Mathew AR, Hitsman B. Negative mood-induced alcohol-seeking is greater in young adults who report depression symptoms, drinking to cope, and subjective reactivity. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;26(2):138–46. https://doi.org/10.1037/pha0000177.

Mitra S, De A, Chowdhury A. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:16. https://doi.org/10.21037/tgh.2019.09.08.

Li P. Spatial distribution characteristics of two liver function indicators reference values in healthy individuals [MA thesis]. Shaanxi Normal University; 2018.

Subramaniyan V, Chakravarthi S, Jegasothy R, Yuanseng W, Fuloria NK, Fuloria S, et al. Alcohol-associated liver disease: a review on its pathophysiology, diagnosis and drug therapy. Toxicol Rep. 2021;8:376–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.toxrep.2021.02.010.

Zhonghua S, Wei H, Hongxian C, country Cgftssodifrot. Alcohol patterns, alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems in five areas in China:1. Alcohol patterns and annual consumption collaborate group for 2nd survey on alcohol drinking in five areas in China. Chin Mental Health J. 2003;08:536–9.

Wang WJ, Xiao P, Xu HQ, Niu JQ, Gao YH. Growing burden of alcoholic liver disease in China: a review. World J Gastroenterol. 2019;25(12):1445–56. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v25.i12.1445.

Qiumao C, Yanjun X, Xiaojun X, Zhenglu H, Zhiyao Z. Investigation on drinking behaviors among residents aged over 18 Years in Guangdong Province. Modern Prevent Med. 2014;41(10):1818–21.

Shengqiong G, Tao L, Liangxian S, Ling L, Dan L, Jie Z. Research on status of alcohol consumption among adult residents in Guizhou Province. Modern Prevent Med. 2016;43(04):658–62+73.

Guansheng M, Danhong Z, Xiaoqi H, Dechun L, Lingzhi K, Xiaoguang Y. The drinking practice of people in China. Acta Nutri Sin. 2005;05:16–9.

Liangpunsakul S, Haber P, McCaughan GW. Alcoholic liver disease in Asia, Europe, and North America. Gastroenterology. 2016;150(8):1786–97. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.043.

Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Shield KD. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2013;59(1):160–8.

Agardh EE, Allebeck P, Flodin P, Wennberg P, Ramstedt M, Knudsen AK, et al. Alcohol-attributed disease burden in four Nordic countries between 2000 and 2017: are the gender gaps narrowing? A comparison using the Global Burden of Disease, Injury and Risk Factor 2017 study. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2021;40(3):431–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13217.

Tiansong Z. Applied methodology for evidence-based medicine. Changsha: Central South University Press; 2014.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members who participated in this work.

Funding

This work was supported by the Six Talent Peaks Project in Jiangsu Province, China (2019, WSN-049), “333 Project” of Jiangsu Province, Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (Nursing Science, 2018, No.87), Research and Innovation Team Project of School of Nursing, Nanjing Medical University, and Graduate Research and Innovation Projects in Jiangsu Province, China (KYCX21_1553), Advantages of general practice in Pudong New Area (PWYq2020-03).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ZZT, YJD and JW contributed to the conception and designing of the study. RZ, MXW, MW, WZ and YC contributed to data collation, statistical analysis, and quality control. ZZT, YJD, LXZ, YC and JW wrote and critically revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Supplement A. Search strategies of different databases. Supplement B. The quality assessment for the included studies. Supplement C. Forest plot of sensitivity analysis. Supplement D. The publication bias for the included studies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, Z., Ding, Y., Zhang, W. et al. Epidemiological characteristics of alcohol-related liver disease in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 23, 1276 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15645-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15645-4