Abstract

Background

Mistrust in science and scientists may adversely influence the rate of COVID-19 vaccination and undermine public health initiatives to reduce virus transmission.

Methods

Students, staff and faculty responded to an email invitation to complete an electronic survey. Surveys included 21-items from the Trust in Science and Scientists Inventory questionnaire. Responses were coded so higher scores indicated a higher trust in science and scientists, A linear regression model including sex, age group, division, race and ethnicity, political affiliation, and history of COVID-19, was used to determine variables significantly associated with trust in science and scientists scores at the p < 0.05 level.

Results

Participants were mostly female (62.1%), Asian (34.7%) and White (39.5%) and students (70.6%). More than half identified their political affiliation as Democrat (65%). In the final regression model, all races and ethnicities had significantly lower mean trust in science and scientists scores than White participants [Black (\(B\)= -0.42, 95% CI: -0.55, -0.43, p < 0.001); Asian (\(B\)= -0.20, 95% CI: -0.24, -0.17, p < 0.001); Latinx (\(B\)= -0.22, 95% CI: -0.27, -0.18, p < 0.001); Other (\(B\)= -0.19, 95% CI: -0.26, -0.11, p < 0.001)]. Compared to those identifying as Democrat, all other political affiliations had significantly lower mean scores. [Republican (\(B\) =-0.49, 95% CI: -0.55, -0.43, p < 0.0001); Independent (\(B\) =-0.29, 95% CI: -0.33, -0.25, p < 0.0001); something else (\(B\) =-0.19, 95% CI: -0.25, -0.12, p < 0.0001)]. Having had COVID-19 (\(B\)= -0.10, 95% CI: -0.15, -0.06, p < 0.001) had significantly lower scores compared to those who did not have COVID-19.

Conclusion

Despite the setting of a major research University, trust in science is highly variable. This study identifies characteristics that could be used to target and curate educational campaigns and university policies to address the COVID19 and future pandemics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Misinformation about COVID-19 and mitigation practices including vaccination has proliferated throughout the pandemic, potentially increasing distrust of science and scientists [1, 2]. Conflicting guidelines and practices for mitigating the spread of the virus (e.g., changing mask mandates) at the state and federal levels in the U.S. produced confusion among the population often resulting in poor health outcomes [3,4,5,6,7]. Wariness of the science surrounding COVID-19 has sparked controversy over safety of the COVID-19 vaccine and increasing hesitancy among certain subgroups in the population [8,9,10,11]. Vaccine hesitancy and denial are likely responsible for a large portion of the estimated 319,000 excess COVID-19 deaths (as of April 30, 2022) that vaccinations could have been prevented in the U.S. [12].

Mistrust in science and scientists is embedded in history especially among certain racial and ethnic groups [9] as a product of structural racism and health disparities [13,14,15]. While public health messaging around the COVID-19 vaccine has targeted underserved communities in the U. S. [16, 17], the percentage receiving at least one dose of the vaccine among those who identified as Black (57%) is less than those identifying as White (63%) and those identifying as Hispanic (65%).[18] Religious beliefs and political affiliation have been associated with suspicion surrounding COVID-19.[19,20,21,22] Furthermore, political affiliation influences individuals’ selection of health information sources, leaving room for misinterpretation of scientific recommendations on mitigation practices [23]. Few studies have investigated trust in science and scientists among students, staff and faculty within a university [24, 25]. Completing more college level science based courses (8 or more) is associated with greater trust in science compared to taking fewer courses (2 or less). [26] Better understanding of science is considered a factor in greater trust in science and scientists [24], however, it is not clear whether characteristics of individuals attending and working in an academic environment reflect similar characteristics associated with trust in science among populations in the U.S. Furthermore, data is lacking whether trust differs among students and faculty based on academic interests for example political science and religious studies. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate characteristics associated with trust in science and scientists among students, staff, and faculty attending or working at a large, diverse, urban university.

Methods

Participants

Participants were students, staff, and faculty at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles, California, a major R-1 research-intensive University. Participants were eligible if they were currently employed or enrolled at USC, were at least 18 years of age, and provided informed consent completed online.

Procedure

This study was approved by the USC Institutional Review Board. Methods and procedures have been published elsewhere [8]. Briefly, all graduate and undergraduate students enrolled at the university in addition to staff and faculty were invited by email to participate in a brief COVID-19 survey. All student, faculty and staff with an institutional email received survey invitations. Duplications were removed based on participant university identification number and date of birth. Participants with completed online consent forms were enrolled. Survey responses from enrolled students, staff and faculty with a university email and completed online consent form were included. Responses were collected from 4/29/2021 to 4/22/2022.

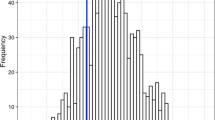

Outcome variable

Trust in science and scientists scores were calculated using responses to the Trust in Science and Scientists Inventory, a validated 21-item questionnaire [2, 26,27,28,29]. Responses to each item ranged from 1” strongly disagree” to 5 “strongly agree”. Items were coded so that a higher score indicated a higher trust in science and scientists, and the 21 items were averaged together to form a single Trust in Science and Scientists score (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.86).[26] Of the number of survey respondents (N = 9684), only participants who completed the Trust in Science and Scientists Inventory were included in the analyses (N = 4237) since this was the outcome variable of interest.

Covariates

Demographic variables included self-reported sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (Black, Asian, Latinx, Other race and ethnicities and White), division (student, staff, and faculty) and age. “Other” race and ethnicity category included participants identifying as multi-racial or as a race/ethnicity other than Black, Asian, Latinx or White. Greater than 80% of students were between ages 18 and 24 years, and ages among staff and faculty ranged between 18 and 85 years. To further investigate whether age is associated with trust in science and scientists, age was categorized into quartiles. Political affiliation (Republican, Democrat, Independent or something else) and self-reported COVID-19 infection status was categorized as “yes” or “no”.

Data analysis

All analyses were performed using STATA version 17.0 (StataCorp, USA). P-values for all analyses were two-sided with a significance level of \(\alpha =0.05\). A multiple linear regression model including all covariates (race and ethnicity, age category, sex, division, political affiliation, and previous COVID-10 status) were entered in a stepwise manner to determine which variables were associated with trust in science and scientists scores. Multicollinearity was checked using the Variance Inflation Factor for each independent variable inputted into the model. Beta coefficients and 95% confidence intervals associated with mean trust in science and scientists score are reported.

Results

Demographic characteristics and mean trust in science and scientist scores are displayed in Table 1. The sample was primarily female (62.1%), Asian (34.7%) and White (39.5%) and were students (70.6%). More than half identified their political affiliation as Democrat (65%). Participants identifying as Black had the lowest mean trust compared to other races and ethnicities (p < 0.0001). Males (v. females; p = 0.002) and those reporting having had COVID-19 (v. not reporting COVID; p < 0.0001) also had lower mean trust in science and scientist scores. Participants reporting political affiliation as Republican had lower scores compared to other affiliations (p < 0.0001).

Multivariate linear regression results are shown in Table 2. All races and ethnicities were significantly lower than White participants [Black (\(B\)= -0.42, 95% CI: -0.55, -0.43, p < 0.001); Asian (\(B\)= -0.20, 95% CI: -0.24, -0.17, p < 0.001); Latinx (\(B\)= -0.22, 95% CI: -0.27, -0.18, p < 0.001); Other (\(B\)= -0.19, 95% CI: -0.26, -0.11, p < 0.001)]. In a post hoc analysis, trust in science and scientists scores among Black participants were significantly lower than Asian (p = 0.002); Latinx (p = 0.009) and Other races and ethnicities (p = 0.012).

All political affiliations [Republican (\(B\) =-0.49, 95% CI: -0.55, -0.43, p < 0.0001); Independent (\(B\) =-0.29, 95% CI: -0.33, -0.25, p < 0.0001); something else (\(B\) =-0.19, 95% CI: -0.25, -0.12, p < 0.0001)] compared to Democrat, and having COVID-19 (\(B\)= -0.10, 95% CI: -0.15, -0.06, p < 0.001) were associated with lower mean trust in science and scientist scores. Only ages 21–24 years had lower scores compared to those in the oldest quartile for age ((\(B\) =-0.07, 95% CI: -0.13, -0.01, p = 0.01). Sex and division were not significant correlates of trust.

Discussion

This study investigated characteristics associated with trust in science and scientists among a sample of students, staff, and faculty at a large diverse university. Results from the analyses identified sex, race and ethnicity, age, political affiliation, and COVID-19 infection status are significantly associated with trust in science and scientists. Previous studies suggested university students are more inclined to value science compared to the general population and therefore have greater trust in science and scientists [27, 30]. Conversely, results from this study suggest characteristics associated with trust in science and scientists may be more aligned with results published in the literature which are based on general population characteristics, and affiliation with an academic institution may be less influential.

In the present study race and ethnicity was significantly associated with trust in science and scientists. These results are consistent with studies highlighting the effect of historical and structural racism against African American and Native American populations in the United States [15, 31,32,33]. Higher education institutions must be considerate of mistrust in science due to structural racism among various ethnic groups on campus.

Only scores among participants ages 21–24 were significant compared to older and younger adults. These results differ from those published by Dohle et al. who conducted a cross-sectional study (N = 962 adults) investigating the association between trust in science and acceptance of COVID-19 preventive measures during spring of 2020. The authors did not find a significant association between age and trust in science; however, the authors included age as a continuous variable rather than categorizing age to determine difference among age groups. We included division in the adjusted model since greater than 80% of student ages were between 18 and 24 years, yet, found lower trust scores among this age group. Because university campuses are highly interactive communities, understanding characteristics associated with complying with COVID-19 mitigation measures to needs further investigation.

Several studies have found political affiliation is a strong predictor of adopting COVID-19 prevention measures such as social distancing and mask wearing [2, 8, 22, 23, 34, 35]. COVID-19 misinformation delivered through different social and news media platforms aligning with certain political ideations have been found to influence acceptance of government public health messaging regarding mitigation measures including vaccination [9, 13, 22]. Despite being a public health crisis, COVID-19 has been politicized negatively impacting new infection and vaccination rates in the United States. This study found trust in science and scientists scores significantly differed among political affiliations with Democrats having the highest scores. Over 60% of the sample in this study identified as Democrats which is greater than reported Democratic political party affiliation, 46.5%, among registered voters in California in 2021 [36]. Further research on health outcomes related to the association of public health messaging and political ideation is needed to improve public health initiatives among individuals with lower trust in scientific based interventions.

Having COVID-19 was observed as a significant factor influencing lower trust scores. Perceived risk level to the virus may have influenced whether individuals were adherent to COVID-19 prevention measures. It is possible those who perceived themselves at higher risk may have adopted prevention measures compared to those who considered themselves to be less at risk. We did not include self-reported COVID-19 prevention behaviors in these analyses; therefore, it is unclear whether trust scores may have been moderated by perceived risk.

The current study adds to the literature in several ways. Survey responses were obtained from a large, diverse sample of students, staff, and faculty from a large research-intensive university in Southern California. Furthermore, our findings suggest trust in science and scientists are influenced by several factors including race and ethnicity, having COVID, and political affiliation. Although results correspond with other published literature, to our knowledge this is the first study to investigate trust in science and scientists among university students, staff, and faculty.

Limitations

This analysis was based on a non-random sample of university students, staff, and faculty who responded to an online survey, and results may not generalize to the larger population. Future studies are needed to investigate correlates of trust in science and scientists among students, staff, and faculty who chose not to participate. Another limitation is self-reported data including COVID-19 infection status. Although we did ask about international student status, greater than 80% of the respondents were domestic students; therefore, we are unable to determine whether scores differed among domestic and international students.

Conclusions

This study identifies factors associated with trust in science and scientists among university students, staff, and faculty including race and ethnicity, age, division within the university (student versus staff and faculty) and political affiliation. Furthermore, this study provides insight into characteristics influencing trust in science and scientists and identify populations that may benefit from targeted education and outreach campaigns. Additionally, these findings may help generate university policies and programs to address future pandemics. More research on the influence of public health messaging and political ideation on health outcomes especially among those with decreased trust in science is needed.

References

Agley J, Xiao Y. Misinformation about COVID-19: evidence for differential latent profiles and a strong association with trust in science. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):89.

Agley J. Assessing changes in US public trust in science amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health. 2020;183:122–5.

Hatcher W. A failure of political communication not a failure of bureaucracy: the danger of presidential misinformation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am Rev Public Adm. 2020;50(6–7):614–20.

DeSalvo K, Hughes B, Bassett M, Benjamin G, Fraser M, Galea S et al. Public health COVID-19 impact assessment: lessons learned and compelling needs. NAM perspectives. 2021;2021.

Hale T, Atav T, Hallas L, Kira B, Phillips T, Petherick A, et al. Variation in US states responses to COVID-19. Blavatnik School of Government; 2020.

Bergquist S, Otten T, Sarich N. COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Health Policy and Technology. 2020;9(4):623–38.

Lyu W, Wehby GL. Community Use of Face Masks and COVID-19: evidence from a natural experiment of State Mandates in the US: study examines impact on COVID-19 growth rates associated with state government mandates requiring face mask use in public. Health Aff. 2020;39(8):1419–25.

Nicolo M, Kawaguchi ES, Ghanem-Uzqueda A, Kim AE, Soto D, Deva S, et al. Characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccination status among staff and faculty of a large, diverse University in Los Angeles: the Trojan Pandemic Response Initiative. Prev Med Rep. 2022;27:101802.

Best AL, Fletcher FE, Kadono M, Warren RC. Institutional distrust among African Americans and building trustworthiness in the COVID-19 response: implications for ethical public health practice. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32(1):90.

Latkin CA, Dayton L, Yi G, Konstantopoulos A, Boodram B. Trust in a COVID-19 vaccine in the US: A social-ecological perspective. Social science & medicine (1982). 2021;270:113684.

Lee RC, Hu H, Kawaguchi ES, Kim AE, Soto DW, Shanker K, et al. COVID-19 booster vaccine attitudes and behaviors among university students and staff in the United States: the USC Trojan pandemic research Initiative. Prev Med Rep. 2022;28:101866.

Health BSoP. Vaccine Preventable Deaths Analysis. 2022.

Willis DE, Andersen JA, Bryant-Moore K, Selig JP, Long CR, Felix HC, et al. COVID‐19 vaccine hesitancy: Race/ethnicity, trust, and fear. Clin Transl Sci. 2021;14(6):2200–7.

Bogart LM, Dong L, Gandhi P, Klein DJ, Smith TL, Ryan S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine intentions and mistrust in a national sample of black Americans. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;113(6):599–611.

Dickinson KL, Roberts JD, Banacos N, Neuberger L, Koebele E, Blanch-Hartigan D, et al. Structural racism and the COVID-19 experience in the United States. Health Secur. 2021;19(S1):14–s26.

Torres C, Ogbu-Nwobodo L, Alsan M, Stanford FC, Banerjee A, Breza E, et al. Effect of physician-delivered COVID-19 public health messages and messages acknowledging racial inequity on black and white adults’ knowledge, beliefs, and Practices related to COVID-19: a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(7):e2117115.

Woko C, Siegel L, Hornik R. An investigation of low COVID-19 vaccination intentions among Black Americans: the role of behavioral beliefs and trust in COVID-19 information sources. J health communication. 2020;25(10):819–26.

Foundation KF. 2022.

Berg MB, Lin L. Predictors of COVID-19 vaccine intentions in the United States: the role of psychosocial health constructs and demographic factors. Transl Behav Med. 2021;11(9):1782–8.

Levin J, Bradshaw M. Determinants of COVID-19 skepticism and SARS-CoV-2 vaccine hesitancy: findings from a national population survey of U.S. adults. BMC Public Health. 2022;22(1):1047.

Luna DS, Bering JM, Halberstadt JB. Public faith in science in the United States through the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2021;2:100103.

Milligan MA, Hoyt DL, Gold AK, Hiserodt M, Otto MW. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance: influential roles of political party and religiosity. Psychol Health Med. 2021:1–11.

Haytko DL, Mai ES, Taillon BJ. COVID-19 information: does political affiliation impact consumer perceptions of trust in the source and intent to comply? Health Mark Q. 2021;38(2–3):98–115.

Schoor C, Schütz A. Science-utility and science-trust associations and how they relate to knowledge about how science works. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(12):e0260586.

Qiao S, Friedman DB, Tam CC, Zeng C, Li X. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among college students in South Carolina: do information sources and trust in information matter? J Am Coll Health. 2022:1–10.

Nadelson L, Jorcyk C, Yang D, Jarratt Smith M, Matson S, Cornell K, et al. I just don’t trust them: the development and validation of an assessment instrument to measure trust in science and scientists. School Sci Math. 2014;114(2):76–86.

Nadelson LS, Hardy KK. Trust in science and scientists and the acceptance of evolution. Evolution: Educ Outreach. 2015;8(1):1–9.

Krüger JT, Höffler TN, Parchmann I. Trust in science and scientists among secondary school students in two out-of-School learning activities. International Journal of Science Education, Part B. 2022:1–15.

Plohl N, Musil B. Modeling compliance with COVID-19 prevention guidelines: the critical role of trust in science. Psychol health Med. 2021;26(1):1–12.

Qiao S, Friedman DB, Tam CC, Zeng C, Li X. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance among college students in South Carolina: do information sources and trust in information matter? Journal of American College Health. 2022:1–10.

Cunningham-Erves J, Mayer CS, Han X, Fike L, Yu C, Tousey PM, et al. Factors influencing intent to receive COVID-19 vaccination among black and white adults in the southeastern United States, October - December 2020. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(12):4761–98.

María Nápoles A, Stewart AL, Strassle PD, Quintero S, Bonilla J, Alhomsi A, et al. Racial/ethnic disparities in intent to obtain a COVID-19 vaccine: a nationally representative United States survey. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101653.

Marrett CB. Racial disparities and COVID-19: the Social Context. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2021;8(3):794–7.

Hamilton LC, Safford TG. Elite cues and the rapid decline in trust in science agencies on COVID-19. Sociol Perspect. 2021;64(5):988–1011.

Young DG, Rasheed H, Bleakley A, Langbaum JB. The politics of mask-wearing: political preferences, reactance, and conflict aversion during COVID. Soc Sci Med. 2022;298:114836.

California PPIo. California Voter and Party Profiles. 2021.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research has been funded by the University of Southern California Office of the Provost and the Keck Medicine Foundation. M. Nicolo is funded by NIH 5T32CA229110-03.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. MN analyzed and interpreted the data and was a major contributor to writing the manuscript. EK assisted with data analyses and interpretation and contributed to the editing of the manuscript. AGU contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. DS was involved in participant recruitment and contributed to writing and editing the manuscript. SD was involved in participant recruitment and editing the manuscript. KS was involved in participant recruitment and editing the manuscript. RL was involved in participants recruitment, database management and editing the manuscript. FG is a co-primary investigator overseeing the study and was involved in supervising the project, manuscript development and editing. JK is a co-primary investigator overseeing the study and was involved in supervising the project, manuscript development and editing. LBG is a co-primary investigator overseeing the study and was involved in supervising the project, manuscript development and editing. AK is a co-primary investigator supervising the study and was involved in overseeing the project, manuscript development and editing. SVO is a co-primary investigator overseeing the study and was involved in supervising the project, manuscript development and editing. HH is a co-primary investigator overseeing the study and was involved in supervising the project, manuscript development and editing. JU is a co-primary investigator overseeing the study and was involved in supervision the project data analyses and interpretation, manuscript development and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Research involving human participants, human material, or human data, must have been performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Review Board. All participants received and signed an informed consent to participate in the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable Availability of data and materials: The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nicolo, M., Kawaguchi, E., Ghanem-Uzqueda, A. et al. Trust in science and scientists among university students, staff, and faculty of a large, diverse university in Los Angeles during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Trojan Pandemic Response Initiative. BMC Public Health 23, 601 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15533-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15533-x