Abstract

Background

Unsafe sex is one of the main morbidity and mortality risk factors associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in young people. Behavioral change interventions for promoting safe sex have lacked specificity and theoretical elements about behavior in their designs, which may have affected the outcomes for HIV/AIDS and STI prevention, as well as for safe sex promotion. This study offers an analysis of the barriers and facilitators that, according to the university students who participated in the focus groups, impede or promote the success of interventions promoting healthy sexuality from the perspective of the actions stakeholders should undertake. In turn, this study proposes intervention hypotheses based on the Behavior Change Wheel which appears as a useful strategy for the design of intervention campaigns.

Methods

Two focus groups were organized with students from Universidad de Santiago de Chile (USACH). The focus groups gathered information about the perceptions of students about sex education and health, risk behaviors in youth sexuality, and rating of HIV/AIDS and STI prevention campaigns. In the focus groups, participants were offered the possibility of presenting solutions for the main problems and limitations detected. After identifying the emerging categories related to each dimension, a COM-B analysis was performed, identifying both the barriers and facilitators of safe sex behaviors that may help orient future interventions.

Results

Two focus groups were organized, which comprised 20 participants with different sexual orientations. After transcription of the dialogues, a qualitative analysis was performed based on three axes: perception about sex education, risk behaviors, and evaluation of HIV/AIDS and STI prevention campaigns. These axes were classified into two groups: barriers or facilitators for safe and healthy sexuality. Finally, based on the Behavior Change Wheel and specifically on its ‘intervention functions’, the barriers and facilitators were integrated into a series of actions to be taken by those responsible for promotion campaigns at Universidad de Santiago. The most prevalent intervention functions are: education (to increase the understanding and self-regulation of the behavior); persuasion (to influence emotional aspects to promote changes) and training (to facilitate the acquisition of skills). These functions indicate that specific actions are necessary for these dimensions to increase the success of promotional campaigns for healthy and safe sexuality.

Conclusions

The content analysis of the focus groups was based on the intervention functions of the Behavior Change Wheel. Specifically, the identification by students of barriers and facilitators for the design of strategies for promoting healthy sexuality is a useful tool, which when complemented with other analyses, may contribute improving the design and implementation of healthy sexuality campaigns among university students.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Unsafe sex is one of the main morbidity and mortality risks in young people [1] as it is associated with sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). The main prevention mechanism is behavioral, through safer sexual practices like the use of condoms. Therefore, understanding this behavior and the context where it takes place is essential for designing theory- and evidence-based behavioral interventions [2] And although there is evidence on combined interventions that promote HIV/STI interventions (biomedical, behavioral and structural) [3] [4], our work will center on behavioral interventions.

These behavioral change interventions require that young people take specific actions to achieve this change, for example, using condoms, gathering information about health consequences, requesting the support of their partners and peer groups, and even redesigning the environment to facilitate access to condoms and HIV testing [5]. These actions are different for each individual, community or context, and thus it is necessary to know the barriers that impede or encourage these specific actions to perform interventions that enhance skill acquisition, increase the motivation to carry out these actions, and make sure that both the physical and social environment are open to them [6].

The prevalence of HIV in the world is heterogeneous; 60% of cases are concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa, with 4.000 new infections each day. Of these, 51% affect women and 31% young people aged 15 to 24. Currently, 37.7 million people are living with HIV in the world. In 2020, there were 1.5 million new cases of HIV in the world and 680,000 deaths associated with AIDS [7].

UNAIDS’ 2020 goals for reducing the number of new cases and deaths associated with HIV were not met [8]. This is partly related to the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). In Latin America, the percentage change of new infections from 2010 to 2020 was 0%, i.e., there was no reduction in new infections; they have remained the same. However, there was a 63% increase in Chile during the same period [7].

According to the 2021 UNAIDS report, Chile has a 0.6 prevalence in the adult population aged 15 to 49, i.e., 6 in 1,000 people live with HIV. The risk of becoming infected with an STI or HIV is not always considered by young people, and their knowledge does not always lead to preventive practices. According to UNAIDS, at the regional level, Chile presents the highest incidence of STI/HIV in Latin America, and young people present a particularly high risk of infection. At the national level, the age brackets with the highest rate of HIV, gonorrhea, hepatitis B, and syphilis are the 5-year brackets of 20–24 and 25–29, where most of the university population is categorized [9].

Regarding prevention, the WHO recommends a comprehensive set of health services for the prevention of STI/HIV, among which are voluntary male circumcision, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and the use of condoms as the main method for this, reducing by 94% the possibility of transmission [10]. However, according to the last data reported in the 2016–2017 National Health Survey, only 1 of 5 young people would use condoms in Chile [11]. Joint and multidisciplinary efforts are needed in terms of prevention to tackle the obstacles faced by university students in the acquisition of behaviors for safe sex.

Among the preventive strategies generated by different organizations and/or governments, individual, group, and community interventions are identified. Regardless of the level of intervention, all share a common goal: to modify the behavior of individuals, identifying both the barriers to achieving health goals, as well as the facilitators based on the positive outcomes of the campaigns.

Aims and objectives

This study has two objectives: first, to analyze the barriers and facilitators that, according to students, impede or favor the success of interventions for the promotion of healthy sexuality; and second, to propose a series of actions based on the analysis of barriers through the Behavior Change Wheel model [12]. Through the latter, we aim to offer structured intervention proposals for health promotion directly based on feedback from young people, who are their potential receptors.

Methods

Behavior change wheel

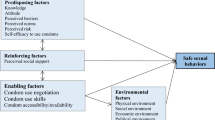

The Behavior Change Wheel (BCW, hereinafter) defines behavior as an interaction between three necessary conditions: (1) Capacity to perform the behavior; (2) Physical or social opportunity to perform the behavior, and; (3) Motivation to perform the behavior. The three variables form the COM-B model (Fig. 1).

Around its nucleus, there is a second layer that comprises 9 intervention functions. Intervention functions are broad categories of means through which an intervention may change behavior. Intervention functions are the following: education, persuasion, incentivization, coercion, training, enablement, modeling, environmental restructuring, and restrictions.

In turn, these functions are linked to the dimensions of COM-B, generating more or less psychological and physical capacities, external or automatic motivation, or physical and/or social opportunity, as seen in Table 1.

The last layer of the wheel, the most external, comprises seven policy categories (environmental/social planning, communication, legislation, service provision, regulation, fiscal measures, and guidelines) that can be used to support the realization of the intervention functions, but that we will not address in this study. The interaction of these layers may provoke a behavior change, and therefore the behavioral wheel model can be employed as a tool for both designing and evaluating interventions.

Design

A descriptive qualitative design was applied, based on collecting information from the target population. Then, focus groups were organized and the information gathered from them was analyzed using content analysis. Finally, the content was classified into three categories or thematic axes: (a) Perceptions about sex education and sexual health; (b) risk behaviors in sexuality; (c) evaluation of STI/HIV prevention campaigns. The script of the focus groups is presented in Appendix 1.

Participants

The target population in our study were students from Universidad de Santiago de Chile (USACH) who attended the programs of Obstetrics, International Studies, English Teaching, Mathematical Engineering, Chemical Engineering and Industrial Design. A group of 40 students were invited to participate in the focus groups. Student representation organizations from USACH and representatives from Student Gender and Sexuality Society (VGS hereinafter) from the same university collaborated with the recruitment process. VGS representatives met the research team several times to learn the fundamentals and scope of the study in detail. These actions enabled the formation of a good rapport and the incorporation of the groups into the study as a specific advisory board, participating in future co-created interventions.

This study used a purposive sample. VGS reached out to students via social networks and e-mails. In a meeting, VGS informed the students who responded to the terms of the research. The research team offered VGS guidelines for participant selection, seeking the highest levels of diversity and complementariness in the approach to the main theme axes and information given. To establish the sample, the saturation principle was employed following Mayan [13]. In this way, saturation was conceived as an analytical instance of an intersubjective approach between the research team and the population participating in the study. Saturation was understood as well as an appraisal of the experience that was aimed at elucidating most aspects of the studied matter from varied significant perspectives. Saturation was achieved from an analytical and procedural perspective, as well as the density and veracity of the information. [14] [15].

Participants did not know the researchers nor the research lines of the study.

Procedure

Two focus groups were organized, both were conducted on the premises of Universidad de Santiago de Chile (USACH) [16]. The groups were led by researchers from USACH, Giuliano Duarte Anselmi, midwife and public health professional, and Eduardo Leiva Pinto, medical anthropologist and expert in qualitative methodologies, while members of the Ethics Committee of USACH participated as observers. Participants, students of the USACH, signed an informed consent prior to the session, and sociodemographic data were collected for sample characterization. The procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of USACH.

The focus groups were conducted considering the following thematic axes: (a) Perceptions about sex education and sexual health; (b) risk behaviors in sexuality; (c) evaluation of STI/HIV prevention campaigns. The script was piloted with students from USACH and VGS members.

Data collection

The sessions were recorded in audio and then transcribed. Transcripts were presented to the VGS members. Subsequently, two researchers (OF, FV) performed an iterative thematic analysis based on the two initial categories:

-

Behavioural Barriers for young people to have safe sex.

In this study, barriers are understood as those aspects related to the perceptions about sex education and sexual health, risk behaviors in sexuality and evaluations of STI/HIV prevention campaigns that according to participants made healthy sex education and sexuality difficult.

-

Behavioural Facilitators for young people to have safe sex.

In this study, facilitators are understood as those aspects related to the perceptions about sex education and sexual health, risk behaviors in sexuality and evaluations of STI/HIV prevention campaigns that according to participants would facilitate healthy sex education and sexuality.

Two researchers (OF and FV) analyzed the transcribed qualitative data collected in the two focus groups, and made a deductive classification for “barriers” and “facilitators”. The work of both was blinded and independent. Both classifications were then put together and if both matched the classification, they were included as such.

Then, a third researcher (MA) identified the inconsistencies between the classifications of the two researchers who coded the data and solved them in a meeting with them, integrating the work of both OF and FV into a single document that was validated through a second meeting with them.

The analysis was conducted manually by the researchers, without support from any specialized software.

Once all interventions were classified into one of the two categories, a specific table was created for each, namely for barriers (Table 2) and facilitators (Table 3). It should be noted that the “facilitators” table contains actions that, according to individuals, contributed to neutralize some of the barriers detected, whether these are coincident or not with the barriers in Table 1.

Actions were classified by researchers NR and MA, into the three dimensions based on the description of the dimensions of the COM-B model included in the Behaviour Change Wheel: capacity, opportunity and motivation.

Results

Out of the 40 students reached, 20 participated in the study. Students who did not show up (8) and those who refused to participate (12) were removed from the sample.

Participants were aged 18 to 25 years. Most of the sample consisted of women (n=14), followed by men (n=5), and 1 participant who reported having a non-conformant gender (n=1). Regarding sexual preferences, participants reported being heterosexual (12), lesbian (4), homosexual (3), and bisexual (1).

The main results of the focus groups are presented following the COREQ criteria [17]. We include an overview of the full COREQ criteria in Appendix 2.

Once all interventions were classified into one of the two categories (barriers and facilitators), a specific table was created for each, namely for barriers (Table 2) and facilitators (Table 3) grouped by the three systematization axis: perceptions about sex education and sexual health, risk behaviors in sexually and evaluation of STI/HIV prevention campaigns.

In order to offer some concrete recommendations about actions to be taken in future sexual health promotion campaigns, a specific table was created (Table 4). In this table all the facilitator actions from Table 3, were integrated; in addition to Table 2 barriers, that were rewritten as positive and specific actions to be potentially taken in Table 4, and linked by the intervention functions of Behaviour Change Wheel Framework. (op. cit.)

The selection of the different «function interventions» was based on the link matrix between COM-B and intervention functions created by Michie, Atkins and West [18]. The researchers OF, FV and MA discussed the classification of the different facilitators and barriers to the COM-B categories (capability, opportunity, or motivation) so those responsible for the health promotion campaigns could perform the behaviors.

Actions were classified by researchers NR and MA, into the three dimensions based on the description of the dimensions of the COM-B model included in the Behaviour Change Wheel: capacity, opportunity, and motivation.

Grouping the results by intervention functions, following the recommendations of Michie et al. (op. cit.) and represented in Fig. 2; Table 5 shows the distribution, in increasing order, of actions and interventions that young people believe should be maintained (facilitators) or should be improved (barriers transformed into actions to be taken) in the intervention campaigns for the promotion of healthy sexuality. As Table 5 shows, Education is by far the most commonly used Intervention function (46.9%), followed by Persuasion (19.64%) and Training (13.63%). Other interventions such as Incetivation, Coercion and Restriction were never used.

Of the 66 actions presented, which should be incorporated in the interventions for promoting healthy and safe sex among young people according to students, 31 (46.9%) were interventions related to the ‘Education’ intervention function, which according to the Behavior Change Wheel (op. cit.), are related to the increase in knowledge and understanding about a specific topic. This result is consistent with this type of study and the structure of its focus groups, which inquired directly about the evaluation of campaigns, perceptions about sexuality, and risky sex behaviors.

Regarding the intervention function of education, it should be noted that participants believe that campaigns should be oriented differently from what has been done in the past and that these should be designed based on quality information, tailored to different groups and their needs. Campaigns should also be delivered by technically trained professionals who hold no prejudices. In addition, campaigns should not be centered only on the biological aspects of sexuality but also address the different expressions of the same, going beyond the description of the possible risks of sex, as this often makes campaigns center on HIV instead of other STIs according to the participants. Furthermore, it is essential to emphasize that sexual relations are a source of pleasure and offer practical rather than only theoretical information.

The second intervention function emerges from the analysis of ‘persuasion’ (19.64%). In the Behavior Change Wheel, persuasion is used as a communicative strategy that induces positive or negative emotions, or even action. In this study, persuasion is related to the need to sometimes influence the trainers themselves so they do not transmit prejudices—for example, about the use of the female condom, or some male-chauvinist attitudes towards the use of condoms during sexual relations—to campaigns. It is also considered vital to influence women’s empowerment in terms of prophylactic measures such as the female condom or even to convince the community that there is no relationship between sexual practices and sexual orientation. Additionally, campaigns should break away from the heteronormative approach to sex and address the topic from a social responsibility perspective. Finally, campaigns should also have elements that promote adherence, for example, gamification, i.e., they should generate positive experiences among people who follow campaigns to promote future adherence.

The intervention function of ‘training’ is the performance of actions aimed at the acquisition of specific competencies according to the BCW.

In the results, this intervention function accounts for 13.63% of the proposed actions (13 actions). This intervention function applies to the proposal of participants for campaigns to have a marked practical nature in terms of offering young people strategies for talking with their friends about the importance of preventive screenings, the capability of verbalizing an HIV + status, and the assertiveness to ask for potential sexual partners negative test results. Participants also indicate the need for enabling the learning of competencies for their own care, and that workshops should be practical in terms of demonstration of the use of female and male condoms, and the creation of materials that show in the most practical way how to use protective devices against STIs.

The intervention function of ‘environmental restructuring’ (with 6 possible actions) accounts for 9.09% of proposals. In this sense, this result is interesting because it reinforces the idea of identifying concrete actions to take in the physical space.

The actions related to ‘environmental restructuring’ refer to aspects such as enabling physical points to deliver condoms safely, reducing barriers, and improving the access and location of condom dispensers, as well as enhancing the conditions for preventive screenings at the university both in terms of location and friendliness of the staff.

Other intervention functions like ‘enablement’ represent 6% of all actions indicated by students (concretely 4). It is noteworthy that ‘enablement’ in the BCW comprises the creation of services and devices that “enable” access to services. Some students indicate that there should be spaces for dialogue with the family, for pre- and post-STI tests follow-ups, and for the generation of specific mobile apps that students can use.

Discussion

The fact that the analysis of barriers and facilitators identified by the students and subsequently processed through the Behavior Change Wheel incorporate such basic intervention functions as education (46.9%), persuasion (19.64%), and training (13.63%) reinforces the idea that students perceive sex education, the addressing of sex risks and especially the campaigns launched as having much space for improvement in terms of both their content and the way it is transmitted. In fact, students emphasize the need for going beyond knowledge, focusing on avoiding stereotypes and giving interventions a more practical approach. In other words, not centering “what” is explained so much as “how”.

Discussing our findings we found coincidences about what function intervention can address the need for sexual health promotion actions in college students in the work of Cassidy et al. [19], who identify the same functions interventions that our study informs (education, environmental restructuring, enablement, modeling, persuasion,) in a study in Canada.

Relating to education and environmental restructuring such function interventions to overcome barriers, we coincide with Bersamin et al. [20] that found that the combination between education (through a specific course) and the opportunity to attend university sexual health services highlight universities as uniquely position to reduce perceived barriers between studies.

Related to sexual health promotion, our study offers a new participative approach, based on BCW, that allows professionals and university actors to not only identify barriers to healthy sexuality, but also to detect opportunities for improvement for the entire community, making young students the main source of knowledge and specific ideas to overcome those barriers.

In the same way, going beyond the classical approach of providing information to students, they themselves identify specific ‘functions interventions’, such as training and persuasion, which offer us new ways of designing a life of healthy sexual promotion.

Chile has the highest incidence of STIs/HIV in Latin America. This is particularly worrying in young people. Interventions in sexual health have failed to address the experiential aspects of youth sexuality, valuing ideal and stereotyped behavior models, discarding first-person narratives and their complexity. Therefore, it is imperative to innovate in the design and implementation of STI/HIV prevention strategies, formulating interventions based on a multidisciplinary, integrative, and situated design that values the experience of the target populations, the reported evidence, and theory.

Our work has some limitations. The first one is related to the fact that the leaders of the focus groups were members of the research team.

This could introduce some bias in the response, which could have been avoided by having external researchers. The second limitation is that the dynamic of the focus group was based on previous categories from the experience of researchers, but not directly on the dimensions of the «sources of behavior» of the BCW (capacity, motivation and opportunity) [12].

Despite these limitations, this study is the first to be carried out in Latin America, with a representative sample of university students and where a topic has been addressed in a replicable framework and from an interdisciplinary perspective. In that sense, this research sought to capture the subjectivity of the target population of the prevention campaigns to give a voice to the people who should benefit from this type of health initiative.

Conclusion

Through this study, we have confirmed that the COM-B methodology like a component of the whole Behaviour Change Wheel, allows for obtaining a series of concrete action proposals to implement at a first decision-making level. We used the BCW to identify which functions interventions can better address the barriers identified by students in sexual health promotion campaigns.

The strengh of our study is not only related with the specific result but with the use of a framework such Behavioural Change Wheel. Authors like Cassidy [19] used before the BCW to improve sexual health service use among university undergraduate students and in our study we confirm that BCW can be a useful tool to asses, monitor and design new intervention. And in addition, to find a new way to identify patterns of lacks, both in capacity, motivation and opportunity, and explore how these needs are adressing with different interventions.

Additionally, we consider that BCW offers both researchers and professional a set of tools, that allow to co-design interventions combining not only barriers detections but identifying facilitators from themselves and not imposed by expert criteria, improving the meaningful involvement of stakeholders in creating new knowledge and mobilising and transferring existing knowledge to support long-term solutions [21].

However, and in future work, our approach should be complemented with other sources of information, both in terms of the APEASE criteria from the Behavioural Change Wheel framework: (affordability, practicability, effectiveness/cost-effectiveness, acceptability, safety, and equity) [18] related with each intervention function to explore its appropriateness for the sexual health promotion campaigns. Additionally, further research can be useful to compare barriers and facilitators, and related functions intervention with the view of other community stakeholders such as doctors, nurses, academic staff, etc.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are publicly available (in Spanish) here.

https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1fM0J-TaXMyl9678kAODgXTCw54CZzrxs?usp=sharingdue.

Futher information are available by the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Murray CJL, Aravkin AY, Zheng P, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi-Kangevari M et al. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet. 17 de octubre de 2020;396(10258):1223–49.

WHO. Behavioural Insights [Internet]. 2021 [citado 19 de noviembre de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.who.int/our-work/science-division/behavioural-insights

OPS/OMS. Prevención Combinada de la Infección por el VIH - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud [Internet]. 2020 [citado 29 de noviembre de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/es/temas/prevencion-combinada-infeccion-por-vih

Combination AIDS, Prevention HIV. Tailoring and Coordinating Biomedical, Behavioural and Structural Strategies to Reduce New HIV Infections. [Internet]. 2010 [citado 29 de noviembre de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2010/20101006_JC2007_Combination_Prevention_paper

Michie S, Richardson M, Johnston M, Abraham C, Francis J, Hardeman W et al. The Behavior Change Technique Taxonomy (v1) of 93 Hierarchically Clustered Techniques: Building an International Consensus for the Reporting of Behavior Change Interventions. Ann Behav Med. 1 de agosto de 2013;46(1):81–95.

Michie S, Johnston M. Theories and techniques of behaviour change: developing a cumulative science of behaviour change. Health Psychol Rev 1 de marzo de. 2012;6(1):1–6.

UNAIDS, Global HIV. & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet [Internet]. 2021 [citado 22 de noviembre de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet

UNAIDS. Implementación de la hoja de ruta de prevención del VIH para 2020 — Cuarto informe de progreso, noviembre de 2020. noviembre de 2020;116.

Cáceres-Burton K. Informe: Situación epidemiológica de las infecciones de transmisión sexual en Chile, 2017. Rev Chil Infectol abril de. 2019;36(2):221–33.

OPS/OMS. Programas Integrales de Distribución de Preservativos y Lubricantes - OPS/OMS | Organización Panamericana de la Salud [Internet]. 2021 [citado 29 de noviembre de 2021]. Disponible en: https://www.paho.org/es/temas/prevencion-combinada-infeccion-por-vih/programas-integrales-distribucion-preservativos

MINSAL, Encuesta Nacional de. Salud 2016–2017. Ministerio de Salud de Chile. Informe Primeros resultados. [Internet]. 2017 [citado 22 de noviembre de 2021]. Disponible en: http://www.encuestas.uc.cl/ens/

Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 23 de abril de. 2011;6(1):42.

Mayan MJ. Essentials of qualitative Inquiry. New York: Routledge; 2016. p. 172.

Denzin NK, Moments. Mixed methods, and paradigm dialogs. Qual Inq 1 de julio de. 2010;16(6):419–27.

Morse JM. The significance of Saturation. Qual Health Res 1 de mayo de. 1995;5(2):147–9.

Duarte-Anselmi G, Leiva-Pinto E, Vanegas-López J, Thomas-Lange J. Experiencias y percepciones sobre sexualidad, riesgo y campañas de prevención de ITS/VIH por estudiantes universitarios. Diseñando una intervención digital. Ciênc saúde coletiva [Internet]. 2022Mar;27(Ciênc. saúde coletiva, 2022 27(3)):909–20. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232022273.05372021.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care J Int Soc Qual Health Care diciembre de. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Michie S, Atkins L, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a guide to designing interventions Susan Michie; Lou Atkins; Robert West. London: Silverback Publishing; 2014. p. 329.

Cassidy C, Steenbeek A, Langille D, Martin-Misener R, Curran J. Designing an intervention to improve sexual health service use among university undergraduate students: a mixed methods study guided by the behaviour change wheel. BMC Public Health 26 de diciembre de. 2019;19(1):1734.

Bersamin M, Fisher DA, Marcell AV, Finan LJ. Reproductive Health Services: barriers to Use among College Students. J Community Health febrero de. 2017;42(1):155–91.

Iniesto F, Charitonos K, Littlejohn A. A review of research with co-design methods in health education. Open Educ Stud 1 de enero de. 2022;4(1):273–95.

Acknowledgements

Concurso Apoyo a la Investigación Clínica DICYT/Facultad de Ciencias Médicas, code 021903 DA_MED, Vicerrectoría de Investigación, Desarrollo e Innovación. Universidad de Santiago de Chile, Usach.

Funding

This manuscript was not commissioned by any organization and received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The corresponding author is the guarantor and declares that all authors meet the criteria for authorship and that no other author who meets the criteria has been omitted.

• A and NR participated in the generation of the original idea and design, elaboration, data analysis and drafting of the document.

• EL-DL-GD participated in the data collection, critical correction of the manuscript and final draft.

• EL-GD participated in data collection, contributed to compliance with the research protocol, data analysis and final draft.

• OF-FV participated in the iterative thematic analysis (barriers and facilitators), critical correction of the manuscript and final draft.

• NR participated in the methodological correction of the manuscript and final draft.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no financial relationship with any organization that may have a real or apparent interest in this work. There are no other relationships or activities that may have influenced the submitted work.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study on which the manuscript is based was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Universidad de Santiago de Chile on May 14, 2020, ethics report No. 177/2020. In addition, written informed consent was obtained from all focus group participants.

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations or all methods were performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Ethics approval attached.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Armayones Ruiz, M., Pinto, E.L., Figueroa, O. et al. Barriers and facilitators for safe sex behaviors in students from universidad de Santiago de Chile (USACH) through the COM-B model. BMC Public Health 23, 677 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15489-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15489-y