Abstract

Background

Out of pocket payment for healthcare remains a barrier to accessing health care services in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Women’s decision-making autonomy may be a strategy for healthcare access and utilization in the region. There is a dearth of evidence on the link between women’s decision-making autonomy and health insurance enrollment. We, therefore, investigated the association between married women’s household decision making autonomy and health insurance enrollment in SSA.

Methods

Demographic and Health Survey data of 29 countries in SSA conducted between 2010 and 2020 were analyzed. Both bivariate and multilevel logistic regression analyses were carried out to investigate the relationship between women’s household decision-making autonomy and health insurance enrollment among married women. The results were presented as an adjusted odds ratio (AOR) and the 95% confidence interval (CI).

Results

The overall coverage of health insurance among married women was 21.3% (95% CI; 19.9-22.7%), with the highest and lowest coverage in Ghana (66.7%) and Burkina Faso (0.5%), respectively. The odds of health insurance enrollment was higher among women who had household decision-making autonomy (AOR = 1.33, 95% CI; 1.03–1.72) compared to women who had no household decision-making autonomy. Other covariates such as women’s age, women’s educational level, husband’s educational level, wealth status, employment status, media exposure, and community socioeconomic status were found to be significantly associated with health insurance enrollment among married women.

Conclusion

Health insurance coverage is commonly low among married women in SSA. Women’s household decision-making autonomy was found to be significantly associated with health insurance enrollment. Health-related policies to improve health insurance coverage should emphasize socioeconomic empowerment of married women in SSA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) emphasize that every individual must have access to quality health services without financial hardship [1]. Since the adoption of the SDGs, there has been a renewed interest in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) to increase efforts towards universal health coverage to ensure equal access to quality health care [2]. More specifically, SDG Goal 3.8 is dedicated to protecting people from the financial risks of catastrophic health care expenditures by minimizing individuals’ out of pocket healthcare-related costs; this has the broader goal of improving population health and promoting socioeconomic well-being and national development [2,3,4]. Estimates by the World Health Organization and the World Bank, show that in 2010, 179 million people worldwide (2.6% of the population) suffered catastrophic healthcare payments greater than 25% of total income or consumption [5]. These estimates revealed that the African region had the fastest increase in catastrophic payments [5].

In LMICs, more than 150 million people endure out of pocket costs related to health-related diseases. Furthermore, over two-thirds suffer from chronic poverty and related problems [6, 7]. While health expenditure per capita in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) has increased by an annualized 3.2% over the last two decades (1995–2014) [8], approximately 36% of healthcare spending in the region continues to be made through direct out of pocket payments, compared to only 22% for the rest of the world [9]. Moreover, existing evidence indicates that catastrophic health expenditures within SSA vary widely - ranging from 1% in Botswana to 25% in Nigeria [10, 11]. Unfortunately, out of pocket financing for healthcare is the main approach to payment for healthcare in SSA, leading to low utilization of and access to healthcare services [5, 12,13,14].

There are inequitable impacts of out of pocket payments on vulnerable sub-groups in LMICs which deters both seeking of and access to healthcare services, and leads to unmet health care needs and inequities. This is especially true for married women, whose autonomy to seek or access health services, make decisions about their own healthcare or how to spend household or personal income, is complicated by patriarchal gender and cultural norms [15,16,17]. Challenges of traditional male authority and control in a marriage lead to tension, conflict, and higher likelihood of domestic violence [18, 19]. Subsequently, the ability to seek or utilize health care facilities is linked to women’s household decision-making autonomy [20]. A recent study in Nigeria by Ifelunini et al. suggested that autonomy in household decisions (i.e., deciding on women’s income and household healthcare services expenditures) increased the likelihood for uptake of maternal healthcare services [21]. Alternatively, when the husband/partner makes the sole or joint decision, the demand is reduced. One such way is having health insurance. Ensuring that women have access to health insurance is one effective way to mitigate the power imbalances that exist due to patriarchal gender and cultural norms.

Another key dimension in seeking and accessing health care is women’s ability to access their own finances, such as employment, income, and health insurance. When investigating issues faced by women in SSA when accessing healthcare, it was found that getting money needed for treatment (50.1%) emerged as the predominant barrier [15]. Indeed, studies have shown that women with access to finances were able to make decisions about seeking health services without consulting others, such as their husband or family members [20, 22].

Since the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, many LMICs have strategically attempted to implement health insurance schemes to provide universal access to health services without undue financial hardships as they work towards universal health coverage [23]. Health Insurance schemes are platforms created and operated by organizations or companies that can be community-based, government-only, or private-for-profit; they offer a shared risk to cover the cost of healthcare services [2]. Ultimately, the purpose of health insurance is to reduce the financial burden of paying out of pocket for health care by pooling resources and sharing the risk of unexpected health events [24,25,26]. Risk-sharing mechanisms are particularly important in SSA, where most countries devote insufficient resources to healthcare and associated commodities, including medications, consequently resulting in out-of-pocket payments [24,25,26]. A study by Ataguba and McIntyre demonstrated the regressive impact of out of pocket payments, noting that using progressive health financing mechanisms (i.e., direct taxes and private health insurance medical schemes) allows the poorest quintiles to pay less as a proportion of their ability to pay [27]. Consequently, groups who face healthcare seeking inequities – particularly women - have a higher likelihood of seeking or accessing healthcare with medical insurance schemes. In Nigeria, Ugbor et al. found that women who participated in community health insurance schemes improved health seeking behaviour by 17% compared to women who did not participate [28], demonstrating the progressive impact of having health-insurance.

Given the importance of women’s decision-making autonomy [20] as well as the relevance of health insurance enrollment in accessing or seeking health care in SSA [29], it is important to consider how the two intersect. Several studies have examined health insurance coverage in SSA, investigating inequality in health insurance coverage in addition to the prevalence and factors associated with coverage in urban regions. Some of these studies have focused on health seeking behaviours of reproductive aged women across a number of SSA countries [3, 28, 30,31,32]. Other literature has also examined women’s decision-making power in the household and its positive influence on the use of health services, particularly in SSA [33, 34]. However, no study to date has assessed the relationship between women’s household decision-making autonomy and health insurance enrollment in SSA. In this study, we investigated determinants, both at the individual/household and community levels, of married women’s health insurance enrollment, with a focus on household decision making autonomy in SSA. Findings from this work will help understand the key determinants of health insurance enrollment, particularly the role of women’s decision-making autonomy, to inform strategies to encourage their participation in health insurance schemes. Additionally, this work focuses on married women who tend to face higher health inequities in seeking or accessing health services. We aim to provide evidence to inform creation of national policies that promote gender equity and women’s empowerment for voiceless and disadvantaged groups, such as women facing domestic violence [20].

Methods

Data source

We pooled data from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) of 29 countries in SSA, conducted between 2010 and 2020. Studied countries were selected based on the availability of the outcome variable and key explanatory variables. The surveys were nationally representative and include data on a wide range of public health related issues including women’s autonomy and health insurance coverage [35]. Details of the sampling procedure and data collection methods are outlined elsewhere [36]. Studied countries were selected based on the availability of the outcome variable (health insurance enrollment), key explanatory variable (women’s household decision-making autonomy) and covariates in their datasets. A total of 226,734 married women in the reproductive age group were included in the analysis. The DHS datasets are available in the public domain and can be accessed at http://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm. Table 1 provides detailed information about selected countries, year of survey, and samples.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable of interest was health insurance status, which included both public and private insurance of participants at the time of interview. If they were covered by either public or private, they were coded “yes” (insured), and individuals not insured were coded “no” [37, 38].

Explanatory variable

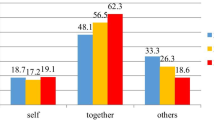

The explanatory variable was women’s household decision-making autonomy. In the DHS, married women were asked three decision-making questions: who decides about (i) “own (respondent’s) health?” (ii) “large household purchases?” and (iii) “family or relatives’ visits?” These variables were used to create the outcome measure of women’s decision-making autonomy. The variables were coded as binary. Married women who made decisions either alone or together with their husbands on all three aforementioned decision-making parameters were considered as empowered and coded as “1”, whereas married women who did not make decision either alone or together with husband on all three decision-making parameters or made decision on one or two decision-making parameters were considered as not empowered and coded “0”, as conceptualized by some previous studies [39, 40]).

Covariates

Based on previous studies [3, 10, 14, 24, 30,31,32], we identified potential individual/household and community level variables as covariates. The individual level variables were women’s age in years (15-19, 20-24, 25-29, 30-34, 35-39, 40-44, 45-49), women’s educational level (no formal education, primary school, secondary school, higher), husband’s educational level (no formal education, primary school, secondary school, higher) and wealth status (poorest, poorer, middle, richer, richest), currently employed (yes, no). The rest were media exposure (no, yes), sex of household head (male, female), parity (less than 5, 5 and above), media exposure (no, yes). The community level variables were place of residence (urban, rural), distance to health facility (big problem, not a big problem), community literacy level (low, medium, high) and community socioeconomic status (low, medium, high).

Statistical analyses

First, descriptive analysis was performed using frequency and percentage distributions to examine respondents’ sociodemographic characteristics and health insurance enrollment. Second, bivariate logistic regression was applied to select the explanatory variable and covariates that had a significant association with health insurance enrollment with p-value less than 0.05 as a cut-off point. Results were presented as crude odds ratios (COR). Third, a multicollinearity test was performed using variance inflation factor (VIF) to check for collinearity among selected variables. The test found no evidence of collinearity among the explanatory variables (Mean VIF = 2.35, Min VIF = 1.0, Max VIF = 5.39). VIF less than 10 are tolerable [41]. In the final step, four different models were constructed using multilevel logistic regressions (MLLR) to assess whether individual/household and community level factors had significant associations with the outcome variables (health insurance enrollment). The first model was a null/empty model (Model 0), which did not have the explanatory variable or covariates, attributed to the primary sampling unit (PSU). The second model (Model I) comprised individual-level factors and the third model (Model II) comprised community-level factors. The last model (Model III) was the complete model that included both the individual/household and community-level factors. Results were presented as adjusted odds ratios (AOR).

All four MLLR models included fixed and random effects [42]. The fixed-effects model showed the association between all included variables and the outcome variable, and the random effects showed the measure of variation in the outcome variable based on PSU, which was measured by Intra-Cluster Correlation Coefficient (ICC) [43]. The model fit was assessed using Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC) [44]. We used the “melogit” command to run the MLLR models. The “svyset” command was used to account for survey weight, cluster and strata. The analyses were performed using Stata version-14 software (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA). We also followed the guidelines for Strengthening Observational studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) [45].

Ethical clearance

We used publicly available secondary data for this study (available at: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm). Ethical procedures were ensured by the institutions that funded, commissioned, and managed the surveys. No further ethical clearance was required. Additional details about data and ethical standards are available at http://goo.gl/ny8T6X.

Results

Background characteristics of respondents

A total of 226,734 married women aged 15–49 were included in this study. One fifth (20.2%) were young between the ages of 15 to 24 years. More than three-fourth (76.3%) of the respondents were from male headed households. About 30.5% and 13.3% of respondents were not currently employed and had no media exposure, respectively. About 60.5% of respondents were rural residents, and 24.4% reported they encountered a big problem when visiting a health facility. About 55.9% of the respondents had decision-making autonomy either alone or together with their husbands on all three decision-making parameters: their own health, to make large household purchases, and to visit families/relatives (Table 2).

Coverage of health insurance

The pooled results showed that about 21.3% of married women were covered by health insurance (Table 2). The lowest coverage was observed in Burkina Faso (0.5%), Chad (0.9%) and Benin (1.1%) respectively, while the highest coverage was seen in Ghana (66.7%), Gabon (43.9%) and Burundi (27.0%) respectively (Fig. 1).

Distribution of health insurance across explanatory variable and covariates

Health insurance coverage varied from 15.7% among women who had no decision-making autonomy to 25.8% among those who had decision-making autonomy. Coverage also varied from 4.9 to 26.0% between adolescent women (15–19 years) and older women (40–44 years). We observed significant difference in health insurance coverage across subgroups of educational level among women and their husbands. For instance, health insurance coverage was 2.7% among women who had no formal education and about 68.1% among women who had higher education. Similarly, health insurance coverage varied from 2.4% among women whose husbands had no formal education to 58.9% among women whose husbands had higher education. The coverage of health insurance also varied from 3.0 to 44.3% between women from the poorest and richest households respectively. Health insurance coverage was 3.7% among women who had no media exposure and 24.0% among those who had media exposure. We further observed that coverage varied from 15.7 to 29.8% between women who lived in rural and urban areas, respectively (Table 2).

Fixed effect (measure of association)

The odds of health insurance coverage was higher among women who had decision-making autonomy (AOR = 1.33, 95% CI; 1.03–1.72) compared to women who had no decision-making autonomy. Women in the age groups of 35–39 years (AOR = 3.02, 95% CI; 1.01–9.05) and 40–44 years (AOR = 3.78, 95% CI; 1.22–11.71) had higher odds of health insurance coverage compared to adolescents aged 15–19 years. The results showed higher odds of health insurance coverage among women who had secondary (AOR = 3.29, 95% CI; 1.48–7.35) and higher education (AOR = 10.62, 95% CI; 4.37–25.81) compared to those who had no formal education. Similarly, women whose husbands had higher education (AOR = 4.32, 95% CI; 1.40-13.33) were more likely to have health insurance coverage compared to those whose husbands had no formal education. We observed higher odds of health insurance coverage among women who were from the middle (AOR = 3.57, 95% CI; 2.01–6.33), richer (AOR = 6.19, 95% CI; 3.37–11.36) and richest (AOR = 11.64, 95% CI; 5.68–23.82) households compared to woman from the poorest households. Women who were employed (AOR = 2.19, 95% CI; 1.60-3.00) had higher odds of health insurance coverage than women who were not employed. Women who were exposed to media (AOR = 1.77, 95% CI; 1.05-3.00) were more likely to be covered than women who were not. We further found higher odds of health insurance coverage among women from female headed household (AOR = 1.48, 95% CI; 1.13–1.94) compared to those from male headed households. Regarding community level, higher odds of health insurance coverage was observed among women who belonged to medium community socioeconomic status (AOR = 1.79, 95% CI; 1.27–2.54) compared to those belonging to low community socioeconomic status (Table 3).

Random effect (measure of variation)

The random effect models of married women’s decision-making autonomy and health insurance are shown in Table 4. We observed that the values of the AIC decreased across the models, indicating a best-fitted model. The ICC in the null model (ICC = 0.59) showed that the odds of health insurance varied across clusters (σ2 = 4.81, 4.14–5.58). The between-cluster variations decreased by 7% in Model I, from 59% in the null model to 52% in Model I. From Model I, the ICC decreased again by 2% in Model II (ICC = 0.50) and then again increased by 2% in the complete model (Model III, ICC = 0.52). These estimates showed that the variations in the likelihood of health insurance can be attributed to the variances in the clustering at the primary sampling units (Table 4).

Discussion

In this study, we examined the association between women’s decision-making autonomy and health insurance coverage among married women in SSA using Demographic and Health Survey datasets of 29 countries in Africa. The pooled results showed that health insurance coverage was approximately 21.3%. The lowest coverage was seen in Burkina Faso (0.5%), Chad (0.9%) and Benin (1.1%) respectively, while highest coverage was observed in Ghana (66.7%), Gabon (43.9%) and Burundi (27.0%) respectively.

Our study found that women with decision-making autonomy had a higher chance of obtaining health insurance than women without decision-making autonomy. This finding is consistent with prior studies where highly autonomous women were noted to have high self-esteem and may not accept gender power differences [46]. There is evidence that health care is critical in reducing maternal and child morbidity and mortality [46,47,48,49]. Although women often make decisions regarding primary health care, a majority do not have health insurance to cover their families [47]. Increasing healthcare costs combined with slow income growth have led to losses in health insurance for women and an increased rate of barriers to accessing needed care and paying medical bills [50]. Educational programs and awareness-raising initiatives aimed at women as informed healthcare users and decision-makers are becoming increasingly important [51]. According to the Pew Internet Project, more and more, women are turning to social media for health care information, to share their health care experiences, as well as make decisions and recommendations, connecting with other women in similar situations [52]. Additionally, women in decision-making positions in health care are known to be trusted sources of health information [51].

Achieving gender equality and empowering all women and girls is the main focus under the seventeen “Sustainable Development Goals” set for transforming the world and improving quality of life [53].

In order to achieve the proposed “Sustainable Development Goals” through appropriate interventions, there is no doubt about the importance of focusing on the position of women in decision-making to address the issue of gender inequality through design of strategies and adoption of immediate intervention measures to empower women [54,55,56].

Married women in older age groups had a higher chance of health insurance coverage compared to adolescents; this is consistent with prior studies in Ghana [57, 58], Nigeria [59], Kenya, Nigeria and Tanzania [3] and Ethiopia [31, 60]. Evidence suggests that older women believe they are more susceptible to diseases as they age [31]. As older age groups become more concerned with their health - and because they are more likely to be employed - they will be more likely to afford or pay for insurance [31].

The findings revealed higher odds of health insurance coverage for married women who had secondary and tertiary education compared to those who had no formal education. Studies in Western Ethiopia and Senegal [61, 62], Nigeria [63], and Ethiopia [29, 64] had similar findings. A possible explanation may be that educated people may understand the principles of health insurance systems and benefit packages [29]. Educated people may be well informed about services and gain a better understanding of their benefits, which drives them to sign up with health insurance schemes. This further suggests that raising women’s awareness through education campaigns can contribute to the successful implementation of health insurance schemes [29].

Likewise, we also found that husband’s educational level associated with coverage of health insurance as seen in prior studies in Nepal and Nigeria [65, 66]. This may be because an educated person understands the principles of health insurance and benefits package [65]. Evidence shows that respondents with higher awareness of health insurance had more chance to be enrolled into health insurance [67]. This is because informed individuals are likely to seek more information about the service, and a better understanding of the benefits of encouraging participation in the CBHI community can contribute to the success of the program [68].

In contrast with previous studies in Ethiopia suggesting that low- and moderate-wealth households were more likely than high-wealth households to enroll in health insurance systems [29, 69, 70], our study showed higher odds of health insurance coverage among women from the wealthiest households compared to the poorest ones. A plausible explanation may be the poor implementation of health care policies which leads wealthy households to prefer to pay -out of pocket for immediate health care services instead of waiting for care through services covered by health insurance [3, 71].

The odds of having health insurance coverage were higher for married women who were employed. This might be due to employment opportunities which enable women to meet specific health needs [72, 73]. It might also be due to employed women being insured by their employer [74]. Women reinvest up to 90% of their income in the health and education of their families, so considering women’s needs and preferences is not only a social investment, but also makes economic sense [74]. Women, especially working mothers, want their parents, spouses, and children to be insured [74]. This finding suggests that encouraging women to take up jobs may improve their socioeconomic status, which may be beneficial to their health and well-being [75].

As previously observed in SSA women exposed to media were more likely to have health insurance compared to those with no media exposure [3]. Evidence suggests that people who listen to radio, watch television, or read newspapers are more likely to sign up for public health insurance because they know and understand the benefits and importance of having coverage [3]. This highlights a central role that the media plays in the dissemination of health-related knowledge and strategies since media is recognized as a powerful tool for successful dissemination and acceptance of health measures [76, 77].

This study further revealed higher odds of health insurance enrollment by the women in female-headed households compared to male-headed households. Preliminary insights into the relationship between gender and healthcare decision-making can be gleaned from the literature on healthcare-seeking behavior, in which several reviews have examined the intersection between home and family roles [78, 79]. A systematic review by Colvin et al. (2013) on health-oriented behavior found that the timely treatment of sick household members is inextricably linked to the degree of influence that the mother has on the final decision to seek external help [79]. Health risk assessments have been shown to manifest differently in male and female householders due to their unique household roles in the study setting. Therefore, it is postulated that women prioritize their direct knowledge of household health needs when deciding to join a health insurance scheme [78]. Existing literature recognizes that the burden of care falls primarily on women, a dynamic that is particularly pronounced when disease occurs in the home setting [79, 80]. This underlying knowledge of the physical, psychological, and economic costs of illness makes the female voice a necessity for understanding and assessing health risks in the household [79].

Higher odds of health insurance enrollment were seen among women of medium community socioeconomic status compared to those of low socioeconomic status. This underscores the impact of systems that provide opportunities for people from a better socioeconomic community to contribute and enroll in health insurance [32].

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has several strengths. First, the study contributes to the body of knowledge by filling in the gaps on the relationship between women’s decision-making ability and health insurance enrollment in SSA. Second, the study was a cross-country analysis with a large and nationally representative sample. Therefore, the results of this study are generalizable to several sub-Saharan African countries and can be used by policy makers and program planners to improve health insurance coverage. However, our results must be interpreted in the context of the following limitations. First, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow the conclusion of a cause-and-effect relationship. Second, since the study was based on self-reported information, memory bias could affect the results. Third, the present study was limited to married women only and therefore cannot be generalized for all women of childbearing age. Finally, and due to data limitations, this study relied on surveys that were collected at different points in time, however, evaluation studies suggest that these differences do not affect the comparability of the data [81].

Conclusion

This study revealed that health insurance coverage is low among married women in SSA. The findings suggest that enhancing women’s autonomy and socioeconomic status, as well as improving media exposure and community socioeconomic conditions, are crucial in promoting health insurance enrollment. Given the critical role of health insurance in ensuring access to healthcare services, it is imperative for policymakers to prioritize the empowerment of women in SSA through various interventions such as education, financial support, and community development programs. Our study highlights the need for targeted health policies aimed at improving health insurance coverage among married women in SSA. By addressing the identified factors that influence health insurance enrollment, these policies can lead to improved health outcomes, reduced healthcare costs, and ultimately, sustainable development in the region.

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available in DHS Program – available datasets [82].

References

World Health Organization (WHO). Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage: 2019 monitoring report [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240029040

Fenny AP, Yates R, Thompson R. Social health insurance schemes in Africa leave out the poor. International Health. 2018 Jan 1;10(1):1–3.

Amu H, Dickson KS, Kumi-Kyereme A, Darteh EKM. Understanding variations in health insurance coverage in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania: Evidence from demographic and health surveys. PLoS One. 2018 Aug 6;13(8):e0201833.

Aryeetey GC, Jehu-Appiah C, Spaan E, Agyepong I, Baltussen R. Costs, equity, efficiency and feasibility of identifying the poor in Ghana’s National Health Insurance Scheme: empirical analysis of various strategies. Trop Med Int Health. 2012 Jan;17(1):43–51.

World Health Organization, International Bank of Reconstruction and Development/World Bank. Tracking universal health coverage: 2017 global monitoring report [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. ; 2017 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259817

Bump J, Cashin C, Chalkidou K, Evans D, González-Pier E, Guo Y et al. Implementing pro-poor universal health coverage. The Lancet Global Health. 2016 Jan 1;4(1):e14–6.

Maeda A, Araujo E, Cashin C, Harris J, Ikegami N, Reich MR. Universal Health Coverage for Inclusive and Sustainable Development: A Synthesis of 11 Country Case Studies [Internet]. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2014 Jun [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/18867

Dieleman J, Campbell M, Chapin A, Eldrenkamp E, Fan VY, Haakenstad A, et al. Evolution and patterns of global health financing 1995–2014: development assistance for health, and government, prepaid private, and out-of-pocket health spending in 184 countries. The Lancet. 2017 May;20(10083):1981–2004.

McIntyre D, Obse AG, Barasa EW, Ataguba JE. Challenges in Financing Universal Health Coverage in Sub-Saharan Africa [Internet]. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Economics and Finance. 2018 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://

Ssewanyana S, Kasirye I. Estimating Catastrophic Health Expenditures from Household surveys: evidence from living standard measurement surveys (LSMS)-Integrated surveys on Agriculture (ISA) from Sub-Saharan Africa. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2020;18(6):781–8.

World Health Organization (WHO). The World Health Report 2005. Make every mother and child count [Internet]. 2005 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9241562900

Garg CC, Karan AK. Reducing out-of-pocket expenditures to reduce poverty: a disaggregated analysis at rural-urban and state level in India. Health Policy Plan. 2009 Mar;24(2):116–28.

Binnendijk E, Dror DM, Gerelle E, Koren R. Estimating willingness-to-pay for health insurance among rural poor in India by reference to Engel’s law. Soc Sci Med. 2013 Jan;76(1):67–73.

Shewamene Z, Tiruneh G, Abraha A, Reshad A, Terefe MM, Shimels T, et al. Barriers to uptake of community-based health insurance in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review. Health Policy Plan. 2021 Nov;11(10):1705–14.

Seidu AA. Mixed effects analysis of factors associated with barriers to accessing healthcare among women in sub-saharan Africa: insights from demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(11):e0241409.

Dominic A, Ogundipe A, Ogundipe O, Determinants of Women Access to Healthcare Services in Sub-Saharan Africa. The Open Public Health Journal [Internet]. 2019 Dec 31 [cited 2023 Feb 8];12(1). Available from: https://openpublichealthjournal.com/VOLUME/12/PAGE/504/FULLTEXT/

Ojanuga DN, Gilbert C. Women’s access to health care in developing countries. Soc Sci Med. 1992 Aug;35(4):613–7.

Kaye DK, Mirembe F, Ekstrom AM, Bantebya G, Johansson A. The Social Construction and Context of domestic violence in Wakiso District, Uganda. Culture. Health & Sexuality. 2005;7(6):625–35.

Pambé MW, Gnoumou B, Kaboré I. Relationship between women’s socioeconomic status and empowerment in Burkina Faso: A focus on participation in decision-making and experience of domestic violence. 2013 Aug 1 [cited 2023 Feb 8]; Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-wp99-working-papers.cfm

Osamor PE, Grady C. Women’s autonomy in health care decision-making in developing countries: a synthesis of the literature. IJWH. 2016 Jun 7;8:191?202

Ifelunini IA, Agbutun AS, Ugwu SC, Ugwu MO. Women autonomy and demand for maternal health services in Nigeria: Evidence from the Nigeria Demographic and Health Survey. African Journal of Reproductive Health [Internet]. 2022 May 3 [cited 2023 Feb 8];26(4). Available from: https://www.ajrh.info/index.php/ajrh/article/view/3290

Nigatu D, Gebremariam A, Abera M, Setegn T, Deribe K. Factors associated with women’s autonomy regarding maternal and child health care utilization in Bale Zone: a community based cross-sectional study.BMC Women’s Health. 2014 Jul3;14(1):79.

Ly MS, Bassoum O, Faye A. Universal health insurance in Africa: a narrative review of the literature on institutional models. BMJ Global Health. 2022 Apr 1;7(4):e008219.

Ekman B. Community-based health insurance in low-income countries: a systematic review of the evidence. Health Policy Plan. 2004 Sep;19(5):249–70.

Musgrove P, Zeramdini R, Carrin G. Basic patterns in national health expenditure. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(2):134–42.

Regional Committee for Africa 56. Health Financing: a Strategy for the African Region Report of the Regional Director [Internet]. WHO. Regional Office for Africa. ; 2006 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Report No.: AFR-RC56-10. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/92642

Ataguba JE, McIntyre D. The incidence of health financing in South Africa: findings from a recent data set. Health Econ Policy Law. 2018 Jan;13(1):68–91.

Ugbor KI, Agbutun AS, Ugbor-Kalu UJ. Investigating the influence of community health insurance on health seeking behaviors and demand for maternal healthcare services in Nigeria. J Public Affairs. 2022;22(4):e2708.

Fite MB, Roba KT, Merga BT, Tefera BN, Beha GA, Gurmessa TT. Factors associated with enrollment for community-based health insurance scheme in western Ethiopia: case-control study. PLoS ONE. 2021 Jun;10(6):e0252303.

Mebratie AD, Sparrow R, Yilma Z, Abebaw D, Alemu G, Bedi AS. The impact of Ethiopia’s pilot community based health insurance scheme on healthcare utilization and cost of care. Soc Sci Med. 2019 Jan;220:112–9.

Terefe B, Alemu TG, Techane MA, Wubneh CA, Assimamaw NT, Belay GM, et al. Spatial distribution and associated factors of community based health insurance coverage in Ethiopia: further analysis of ethiopian demography and health survey, 2019. BMC Public Health. 2022 Aug;10(1):1523.

Barasa E, Kazungu J, Nguhiu P, Ravishankar N. Examining the level and inequality in health insurance coverage in 36 sub-Saharan African countries. BMJ Global Health. 2021 Apr 1;6(4):e004712.

Zegeye B, Ahinkorah BO, Idriss-Wheelr D, Oladimeji O, Olorunsaiye CZ, Yaya S. Predictors of institutional delivery service utilization among women of reproductive age in Senegal: a population-based study. Archives of Public Health. 2021 Jan;11(1):5.

Tiruneh FN, Chuang KY, Chuang YC. Women’s autonomy and maternal healthcare service utilization in Ethiopia.BMC Health Services Research. 2017 Nov13;17(1):718.

Calvès AE. «Empowerment»: généalogie d’un concept clé du discours contemporain sur le développement. Revue Tiers Monde. 2009;200(4):735.

The DHS Program - Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). DHS Overview [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey-Types/dHs.cfm

The DHS Program - Demographic and Health Survey (DHS). Guide to DHS Statistics DHS-7: Analyzing DHS Data [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/Analyzing_DHS_Data.htm

Aboagye RG, Okyere J, Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Zegeye B, Amu H, et al. Health insurance coverage and timely antenatal care attendance in sub-saharan Africa. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Feb;11(1):181.

Croft TN, Marshall AMJ, Allen CK. Guide to DHS Statistics [Internet]. Rockville, Maryland, USA:ICF; 2018 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/index.cfm

Zegeye B, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Seidu AA, Olorunsaiye CZ, Yaya S. Women’s decision-making power and knowledge of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Women’s Health. 2022 Apr 12;22(1):115.

Zegeye B, Anyiam FE, Ahinkorah BO, Ameyaw EK, Budu E, Seidu AA, et al. Women’s decision-making capacity and its association with comprehensive knowledge of HIV/AIDS in 23 sub-saharan african countries. Archives of Public Health. 2022 Apr;6(1):111.

HIS Markit. Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://onlinehelp.ihs.com/Energy/AnalyticsExplorer/AE_6.0/Webhelp/content/analyticsexplorer/VIF.htm

Austin PC, Merlo J. Intermediate and advanced topics in multilevel logistic regression analysis. Stat Med. 2017 Sep;10(20):3257–77.

Perinetti G, StaTips Part IV. Selection, interpretation and reporting of the intraclass correlation coefficient. sejodr [Internet]. 2018 May 14 [cited 2023 Feb 8];5(1). Available from: http://aseestant.ceon.rs/index.php/sejodr/article/view/17434

de-Graft Acquah H. Comparison of Akaike information criterion (AIC) and bayesian information criterion (BIC) in selection of an asymmetric price relationship. J Dev Agricultural Econ. 2010 Feb;1:2:1–6.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies.BMJ. 2007 Oct18;335(7624):806–8.

Kassahun A, Zewdie A. Decision-making autonomy in maternal health service use and associated factors among women in Mettu District, Southwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022 May 2;12(5):e059307.

Mullany BC, Becker S, Hindin MJ. The impact of including husbands in antenatal health education services on maternal health practices in urban Nepal: results from a randomized controlled trial. Health Educ Res. 2007 Apr;22(2):166–76.

Allendorf K. The quality of Family Relationships and maternal Health Care Use in India. Stud Fam Plann. 2010 Dec;41(4):263–76.

Budu E, Ahinkorah BO, Seidu AA, Hagan JE, Agbemavi W, Frimpong JB, et al. Child marriage and sexual autonomy among women in Sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from 31 demographic and health surveys. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Apr;3(7):3754.

Robertson R, Collins SR. Women at Risk: Why Increasing Numbers of Women Are Failing to Get the Health Care They Need and How the Affordable Care Act Will Help | Commonwealth Fund [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2023 Feb 8] p. 24. Available from: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2011/may/women-risk-why-increasing-numbers-women-are-failing-get-health

Matoff-Stepp S, Applebaum B, Pooler J, Kavanagh E. Women as health care decision-makers: implications for health care coverage in the United States. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2014 Nov;25(4):1507–13.

Duggan M, Brenner J. The Demographics of Social Media Users — 2012 [Internet]. Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech. 2013 [cited 2023 Feb 9]. Available from: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2013/02/14/the-demographics-of-social-media-users-2012/

United Nations (UN) Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development | Department of Economic and Social Affairs [Internet]. New York. ; 2015 [cited 2023 Feb 9]. Available from: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda

Kabeer N. Gender equality and women’s empowerment: A critical analysis of the third millennium development goal 1. Gender & Development. 2005 Mar 1;13(1):13–24.

Pratley P. Associations between quantitative measures of women’s empowerment and access to care and health status for mothers and their children: a systematic review of evidence from the developing world. Soc Sci Med. 2016 Nov;169:119–31.

Upadhyay UD, Gipson JD, Withers M, Lewis S, Ciaraldi EJ, Fraser A, et al. Women’s empowerment and fertility: a review of the literature. Soc Sci Med. 2014 Aug;115:111–20.

Badu E, Agyei-Baffour P, Ofori Acheampong I, Preprah Opoku M, Addai-Donkor K. Households Sociodemographic Profile as Predictors of Health Insurance Uptake and Service Utilization: A Cross-Sectional Study in a Municipality of Ghana. Advances in Public Health. 2018 Mar 14;2018:e7814206.

Duku SKO. Differences in the determinants of health insurance enrolment among working-age adults in two regions in Ghana. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018 May;29(1):384.

Aregbeshola BS, Khan SM. Predictors of Enrolment in the National Health Insurance Scheme Among Women of Reproductive Age in Nigeria.Int J Health Policy Manag. 2018 Aug6;7(11):1015–23.

Kebede SA, Liyew AM, Tesema GA, Agegnehu CD, Teshale AB, Alem AZ, et al. Spatial distribution and associated factors of health insurance coverage in Ethiopia: further analysis of Ethiopia demographic and health survey, 2016. Archives of Public Health. 2020 Mar;16(1):25.

Jütting J. Health Insurance for the Poor?: Determinants of Participation in Community-Based Health Insurance Schemes in Rural Senegal [Internet]. Paris: OECD; 2003 Jan [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/health-insurance-for-the-poor_006580410672

Negash B, Dessie Y, Gobena T, Tefera B. Community Based Health Insurance Utilization and Associated Factors among Informal Workers in Gida Ayana District, Oromia Region, West Ethiopia. 2019 Jan 1;13–22.

Ogben C, Ilesanmi O. Community based health insurance scheme: Preferences of rural dwellers of the federal capital territory Abuja, Nigeria. J Public Health Afr. 2018 Jul 11;9(1):540.

Taddesse G, Atnafu DD, Ketemaw A, Alemu Y. Determinants of enrollment decision in the community-based health insurance, North West Ethiopia: a case-control study.Globalization and Health. 2020 Jan6;16(1):4.

Paudel DR. Factors Affecting Enrollment in Government Health Insurance Program in Kailali District.J Nepal Health Res Counc. 2019 Nov14;17(3):388–93.

Adewole DA, Akanbi SA, Osungbade KO, Bello S. Expanding health insurance scheme in the informal sector in Nigeria: awareness as a potential demand-side tool. The Pan African Medical Journal [Internet]. 2017 May 19 [cited 2023 Feb 8]; Available from: https://www.scienceopen.com/document?vid=533e92a1-4a8440b2-ab6b-a3a6f2cf126c

Kebede KM, Geberetsadik SM. Household satisfaction with community-based health insurance scheme and associated factors in piloted Sheko district; Southwest Ethiopia. PLoS ONE. 2019 May;13(5):e0216411.

Acharya D, Devkota B, Gautam K, Bhattarai R. Association of information, education, and communication with enrolment in health insurance: a case of Nepal.Archives of Public Health. 2020 Dec14;78(1):135.

Derseh A, Sparrow RA, Debebe ZY, Alemu G, Bedi AS. Enrolment in Ethiopia’s Community Based Health Insurance Scheme. ISS Working Papers - General Series [Internet]. 2013 Dec 20 [cited 2023 Feb 8]; Available from: https://ideas.repec.org//p/ems/euriss/50221.html

Kado A, Merga BT, Adem HA, Dessie Y, Geda B. Willingness to pay for community-based Health Insurance Scheme and Associated factors among Rural Communities in Gemmachis District, Eastern Ethiopia. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2020;12:609–18.

Kotoh AM, Van der Geest S. Why are the poor less covered in Ghana’s national health insurance? A critical analysis of policy and practice.International Journal for Equity in Health. 2016 Feb25;15(1):34.

Zegeye B, El-Khatib Z, Ameyaw EK, Seidu AA, Ahinkorah BO, Keetile M, et al. Breaking barriers to Healthcare Access: a multilevel analysis of individual- and community-level factors affecting women’s Access to Healthcare Services in Benin. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jan;17(2):750.

Zegeye B, Adjei N, Ahinkorah B, Ameyaw E, Budu E, Seidu AA, et al. Barriers and facilitators to Accessing Health Care Services among Married Women in Ethiopia: a multi-level analysis of the Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey. Int J Translational Med Res Public Health. 2021 Oct;26:5:184.

Louat N, Women. and insurance – a promising combination [Internet]. World Bank Blogs. 2015 [cited 2023 Feb 8]. Available from: https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/women-and-insurance-promising-combination

Shao L, Wang Y, Wang X, Ji L, Huang R. Factors associated with health insurance ownership among women of reproductive age: A multicountry study in sub-Saharan Africa. PLOS ONE. 2022 Apr 12;17(4):e0264377.

Naveena N. Importance of Mass Media in communicating health messages: an analysis. IOSR J Humanit Social Sci. 2015;20(2):36–41.

Saraf RA, Balamurugan J. The Role of Mass Media in Health Care Development: A Review Article.JoARJMC. 2018 Feb27;05(01):39–43.

Oraro T, Ngube N, Atohmbom GY, Srivastava S, Wyss K. The influence of gender and household headship on voluntary health insurance: the case of North-West Cameroon. Health Policy Plan. 2018 Mar 1;33(2):163–70.

Colvin CJ, Smith HJ, Swartz A, Ahs JW, de Heer J, Opiyo N, et al. Understanding careseeking for child illness in sub-saharan Africa: a systematic review and conceptual framework based on qualitative research of household recognition and response to child diarrhoea, pneumonia and malaria. Soc Sci Med. 2013 Jun;86:66–78.

Richards E, Theobald S, George A, Kim JC, Rudert C, Jehan K, et al. Going beyond the surface: gendered intra-household bargaining as a social determinant of child health and nutrition in low and middle income countries. Soc Sci Med. 2013 Oct;1:95:24–33.

Robinson J, Godbey G. Time for life: the surprising Ways Americans Use their time. Penn State Press; 2010. p. 428.

The DHS Program. The DHS Program - Available Datasets [Internet]. 2023 [cited 2023 Feb 9]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the Demographic and Health Surveys Program for making the DHS data available, and we thank the women who participated in the surveys.

Funding

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SY and BZ contributed to the conception and design of the study, interpreted the data, prepared the manuscript, and led the paper. DIW, BOA, EKA, AS and NKA helped with data analysis, provided technical support in interpretation of results and critically reviewed the manuscript for its intellectual content. SY had final responsibility to submit. All authors read and revised drafts of the paper and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval was not required since the data is available to the public domain.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zegeye, B., Idriss-Wheeler, D., Ahinkorah, B.O. et al. Association between women’s household decision-making autonomy and health insurance enrollment in sub-saharan Africa. BMC Public Health 23, 610 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15434-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15434-z