Abstract

Background

Evidence has demonstrated that excess sodium intake is associated with development of several non-communicable diseases. The main source of sodium is salt. Therefore, reducing salt intake in foods is an important global public health effort to achieve sodium reduction and improve health. This study aimed to model salt intake reduction with 'umami' substances among Japanese adults. The umami substances considered in this study include glutamate or monosodium glutamates (MSG), calcium diglutamate (CDG), inosinate, and guanylate.

Methods

A total of 21,805 participants aged 57.8 years on average from the National Health and Nutrition Survey was used in the analysis. First, we employed a multivariable linear regression approach with overall salt intake (g/day) as a dependent variable, adjusting for food items and other covariates to estimate the contribution of salt intake from each food item that was selected through an extensive literature review. Assuming the participants already consume low-sodium products, we considered three scenarios in which salt intake could be reduced with the additional umami substances up to 30%, 60% and 100%. We estimated the total amount of population-level salt reduction for each scenario by age and gender. Under the 100% scenario, the Japan’s achievement rates against the national and global salt intake reduction goals were also calculated.

Results

Without compromising the taste, the 100% or universal incorporation of umami substances into food items reduced the salt intake of Japanese adults by 12.8–22.3% at the population-level average, which is equivalent to 1.27–2.22 g of salt reduction. The universal incorporation of umami substances into food items changed daily mean salt intake of the total population from 9.95 g to 7.73 g: 10.83 g to 8.40 g for men and 9.21 g to 7.17 g for women, respectively. This study suggested that approximately 60% of Japanese adults could achieve the national dietary goal of 8 g/day, while only 7.6% would meet the global recommendation of 5.0 g/day.

Conclusions

Our study provides essential information on the potential salt reduction with umami substances. The universal incorporation of umami substances into food items would enable the Japanese to achieve the national dietary goal. However, the reduced salt intake level still falls short of the global dietary recommendation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main text

Background

The latest Global Burden of Disease Study 2019 (GBD) highlighted that the global prevalence of non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and inadequate public health efforts to control risk factors may have spurred the pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [1]. In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed the NCDs Global Monitoring Framework, in which nine NCDs prevention targets were set [2]. Of the nine targets, the only target specifically related to nutrients is a 30% relative reduction in mean population intake of salt/sodium between 2011 and 2025 [2]. Since then, many campaigns aiming at reducing salt, the main source of sodium, have been initiated around the world [3], and the global salt reduction movement has been accelerated [4,5,6]. However, no country has yet to achieve the 30% reduction goal [7]. In the GBD 2019, high salt intake was listed as one of the top dietary risks contributing to the global burden of disease [8] highlighting the need for an urgent approach.

Japan is one of the countries that are globally recognized for prolonged longevity [9]. However, a high salt intake is a major dietary risk factor for both mortality and morbidity of its population [8, 10]. Japan's nationwide population-based campaign for salt reduction started in 1960s and successfully reduced the population's salt intake and mortality resulting from stroke over time [11]. According to the National Nutrition Survey (NNS), which was renamed to the National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHNS) in 2013, the daily salt intake has steadily decreased from 14.5 g in 1973 to 9.5 g in 2017 [12]. However, the Japanese generally consume more salt than people in other countries [13]. For instance, the population average sodium intake in 2010 was 4.89 g/day (12.23 g/day of salt intake) in Japan, whereas those in the United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) were 3.61 g/day (9.03 g/day of salt intake) and 3.60 g/day (9.00 g/day of salt intake), respectively [13]. The government aims to reduce the daily salt intake of Japanese adults to 8 g by 2023 in their 10-year national health promotion plan, titled the Second Term of National Health Promotion Movement in the Twenty-First Century, also known as "Health Japan 21 (the second term)" [14]. Another dietary guideline is called the Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese (DRIs), which proposes reference values for the intake of energy and nutrients to prevent lifestyle-related diseases and extend healthy life expectancy [15]. The DRIs recommend daily salt intake of 7.5 g/day for men and 6.5 g/day for women. However, the average salt intake among Japanese adults remains higher than the recommendations made by both guidelines. The targets set for the Japanese is unlikely to be attained if current trends persist [16, 17].

Sodium replacement in foods is one of the most widely used approaches to reduce salt intake. The technical challenge is to ensure that the sodium alternative is palatable and safe to eat [18]. Umami is a common and familiar taste in Japanese cuisine, and perhaps globally better known as the fifth flavour, in addition to the classic four tastes: saltiness, sweetness, bitterness, and sourness, discovered by the Japanese scientist in 1908 [19]. Umami substances, including glutamate or monosodium glutamates (MSG), calcium diglutamate (CDG), inosinate and guanylate, have been proposed as enhancers of savory taste when combined with sodium chloride (NaCl) [20,21,22]. A large number of studies have suggested the potential use of umami substances as a healthy and natural solution for salt intake reduction [23,24,25]. In recent years, academic institutions, such as the Institute of Medicine in the United States, have identified umami substances as candidates for practical salt intake reduction alternatives [18]. Wallace et al. (2019) estimated that incorporating MSG into a savoury seasoning of processed foods in the United States could reduce salt intake of the population by at least 3 to 8% [26]. However, given the fact that the source of salt intake is highly dependent on the dietary habits and the cooking processes in each country [27], the effectiveness of the umami substances for reducing salt intake at the population level in the context of other cultures is not well known. Therefore, our study aims to investigate the effects of umami substances on the daily salt (NaCl) intake reduction among Japanese adults using the NHNS data.

Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a cross-sectional study using the de-identified national data from the 2016 NHNS. The NHNS is a nationally representative household survey conducted annually by the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare (MHLW) to collect data on the population's dietary habits, nutrition intake and lifestyle [28]. Residents above the age of one were selected from the census enumeration areas using a stratified single-stage cluster sample design. The 2016 survey, the latest large-scale survey data available from the NHNS at the time of the study, is comprised of 24,187 households randomly selected from 475 districts. The response rate of the survey was 44.4%. The NHNS consists of three parts: 1) physical examination, 2) an in-person survey and weighted single-day dietary record of households, and 3) a self-reported lifestyle questionnaire. Details of the survey design and the procedures are available elsewhere [16, 28]. In the present analysis, we included persons aged 20 years or older as Health Japan 21 requires the age group to complete the dietary intake data. We further excluded participants who reported daily consumption of less than 1.5 g of salt, the minimum physiological requirement for survival, assuming that the data may not reflect their diet accurately or may be measurement error.

This study was performed under the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, the University of Tokyo (authorization number 11964). The ethical committee waived the need for informed consent because this study conducted a secondary analysis using anonymized data routinely collected by the MHLW.

Dietary assessment

The dietary intake survey was conducted on a single designated day for household representatives, who were usually responsible for food preparation. Trained interviewers, mainly registered dietitians, instructed household representatives on how to measure the food and beverages consumed by members of the household and checked their compliance with the survey. The proportion of shared dishes, food waste, and foods eaten out were recorded by the household representatives. The nutrient intake and food consumption were estimated by experts using the dietary record and the corresponding food composition list of the Japanese Standard Tables of Food Composition (7th revised edition) [29]. In addition, food intake (g/day) and overall sodium intake (mg/d) were recorded. Salt intake (g) was defined as sodium (mg) × 2.54/1,000. NHNS did not measure urine sodium.

Salt intake modelling

We have conducted an extensive review of the scientific literatures, and found that umami substances, such as glutamate or MSG, CDG, inosinate, and guanylate, have been used to reduce salt in various mainstream products. Table 1 shows the percentage reduction of salt intake in each food item estimated by previous studies using one or more umami substances. The food items listed in Table 1 were then matched with the predetermined 13 NHNS food groups, and assumed the salt reduction rate for each NHNS food group to be used in our analyses, in consultation with food and nutrition experts (co-authors). In addition, we assumed that the study participants already consume some low-sodium food items containing umami substances in their diet. Therefore, the market share of low-sodium food products was used as a proxy indicator of the baseline consumption of low-sodium foods [30]. This market share was estimated from data of the total sales and the sales of low-sodium foods acquired from the surveys conducted in 2017 by Fuji Keizai Management Co., Ltd. (a Japanese market research company). Low-sodium food products were defined as products labelled with “reduced salt,” “salt cut,” “salt off,” or “no salt” on the package. The market share of low-sodium food products for each food group was also summarized in Table 1. We considered three scenarios in which consumers could potentially reduce their salt intake with the additional umami substances from the baseline to 30% (30-percent scenario), 60% (60-percent scenario) and 100% (100-percent scenario or universal incorporation scenario).

Statistical analysis

We first constructed a linear regression model with overall daily salt intake (g/day, continuous) as a dependent variable. To estimate the salt intake contribution from the 13 food groups (continued) to the overall salt intake, we included age (continuous), sex (dichotomous) and food intake (g/day) from the 13 food groups and the food items (continuous) in the following model (1).

where \({Y}_{i}\) and \({X}_{ji}\) (for j = 1, …,13) are the overall daily salt intake and the food intake (g/day) from each of the 13 food groups for the ith individual, respectively. \({Z}_{i}\) is the covariate vector for the remaining 35 food items, sex and age for the ith individual. \(\alpha , {\beta }_{j}, \gamma\) are regression coefficients and \({\epsilon }_{i}\) is a gaussian error term. The regression coefficients are estimated by ordinary least squared method.

The food group-specific upper and lower changes in salt intake by umami substance incorporation were estimated using the current market share of low-sodium products for the jth food group (denoted as \({M}_{j}\)), the upper and lower salt intake reduction rates for the jth food group (denoted as \({U}_{j}\) and \({L}_{j}\), respectively), as well as the scenario-based increased consumption (denoted as \({S}_{k}\)= 30, 60 or 100% increase (k = 1, 2, 3)), as follows.

The first term indicates the original salt intake contribution of the jth food group to the overall salt intake. In the second term, \({U}_{j}\) indicates how much salt intake we can reduce by incorporating umami substances into food groups. Finally, \(\left({S}_{k}-{M}_{j}\right)\) indicates how much salt intake we can change into that from low-sodium products.

The baseline and reduced salt intakes among consumers of each food group, and the proportion of salt intake from each food group to the total salt intake were estimated for the total population, men, and women in the three scenarios.

The achieving rate of the salt intake reduction goals when umami substances are universally incorporated into all the food groups were then calculated by age groups and sex. Health Japan 21’s dietary goal is defined as a daily mean salt intake of less than 8 g [14], while that of the DRIs is 7.5 g for men and 6.5 g for women [15]. The WHO, on the other hand, recommends a daily salt intake of 5.0 g [59]. We used STATA version 16 for all analyses (Stata Corp LLC).

Results

A total of 30,820 people joined the NHNS survey in 2016. We excluded ineligible subjects who were younger than 20 years old (n = 4,595) and consumed less than 1.5 g of salt per day (n = 46). 4,374 subjects had missing values on dietary intake. Finally, a sample of 21,805 Japanese persons with an average age of 57.8 (standard deviation [SD] 17.6) years were used in our analysis. Overall, the daily mean salt intake among the Japanese population was 9.95 g, which is higher than the daily salt intake recommended by Health Japan 21, the DRIs or the WHO.

The sex- and age-specific daily mean salt intake and the achieving rate of the salt intake reduction goals are shown in Table 2. Salt intake was likely to be higher among older persons than younger persons. Of the total population, 28.7% has already achieved the dietary goal of Health Japan 21, while 15.3% and 2.8% have achieved the dietary goals of the DRIs and the WHO, respectively. Men had higher salt intake than women in all age groups. The daily mean salt intake was the highest among men aged 60–69 years (11.43 g) and women aged 70–79 years (9.72 g), while the lowest among men (10.37 g) and women (8.60 g) both aged 20–29 years. The difference in daily mean salt intake between the highest and the lowest groups was 2.83 g. The rate of achieving the dietary goals was higher in women than men across all age groups.

The sex-specific salt intake and potential reduction of salt intake estimated for each food group in three scenarios are presented in Table 3. The consumption of food items in each food group by the participants on any given day during the survey varied. The percentages of the participants who consumed the food items in each food group, i.e., “consumers,” were high for other seasonings (97.9%), soy sauce (85.9%), seasoning salt (83.1%), and miso paste (69.3%), and low for beef (24.71%), cheese (17.3%), butter (14.9%), margarine (14.4%) and other confectionery (15.2%). Compared to women, men were more likely to consume salt, soy sauce, spices and other, ham and sausage, beef, and pickled vegetable, and less likely to consume cheese and other confectionery. The consumers of soy sauce, seasoning salt, and miso paste took more than one gram of salt daily from each food group, and all participants consumed food items from at least one food group.

In the universal incorporation scenario where consumers could potentially reduce their salt intake up to 100% with the additional umami substances, the highest amount of expected salt reduction was found in soy sauce (0.45–0.68 g), followed by cheese (0.28–0.51 g), pickled vegetable (0.50 g), ham and sausage (0.11–0.49 g), seasoning salt (0.23–0.44 g) and miso paste (0.19–0.45 g). Negligible reductions in salt intake could be expected for spice and others, beef, and other confectionery (< 0.1 g).

Table 4 presents proportion of salt intake from each food group to overall salt intake, and potential salt intake reduction with the additional umami substances in the universal incorporation scenario by sex. Among all participants, soy sauce (12.5%), miso paste (9.7%), and seasoning salt (8.9%) were the major contributors to the overall daily salt intake. In contrast, spice and others, beef, cheese, butter, margarine, and other confectionery were the minor sources of salt intake (< 1%). Although high reduction of salt intake was found in cheese among the cheese consumers (0.28–0.51 g), there was less impact at the population level (0.05–0.09 g) because there were few cheese consumers among the participants. The total daily mean salt intake from all the food groups was 5.06 g for all the participants, resulting in a 48.0% salt intake contribution to the overall salt intake. Thus, by universally incorporating umami substances into the food groups, salt intake could be reduced by an average of 1.27–2.22 g among the total population (with an average reduction rate of 12.0–21.1%). This corresponds to a reduction of 12.8–22.3% in the average salt intake among the total population (not shown in the table).

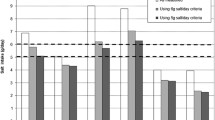

Figure 1 describes distributions of daily salt intake among the total and sex-specific population before and after the universal incorporation of umami substances into food items. It is obvious that higher proportions of the population in both sexes came to consume less amount of salt intake after the universal incorporation of umami substances into food groups. Table 5 shows sex- and age-specific daily mean salt intake estimated after umami substances are universally incorporated into the food items and their achieving rates of the salt reduction goals set by Health Japan 21, the DRIs and the WHO. While the salt intake still varied by sex and age groups, the difference in the mean salt intake between the highest and the lowest groups was slightly smaller when umami substances were universally incorporated into food items. The daily mean salt intake of all the participants in the universal incorporation scenario was 7.73–8.68 g; thereby, suggesting a possibility to achieve Health Japan 21’s goal of consuming less than 8 g of daily salt intake by 2023. Moreover, the rate of those who achieve Health Japan 21’s dietary goal increased from 19.6% to 31.2–46.6% for men and 36.9% to 53.6–70.8% for women under the scenario. While approximately 23.9–36.7% of men and 25.6–39.2% of women could achieve the recommended daily salt intake outlined by the DRIs, only 2.2–3.8% of men and 6.4–10.8% of women were expected to achieve the WHO’s dietary goal: 5 g of daily salt intake, in the universal incorporation scenario.

Distributions of daily salt intake among the total and sex-specific population before and after the universal incorporation of umami substances into food items in (A) the total population, by sex of (B) men, and (C) women, NHNS 2016. The grey bars indicate the distributions of daily salt intake before the universal incorporation of umami substances into food items. The blue bars indicate the distributions of daily salt intake after the universal incorporation of umami substances into food items

Discussion

Excess salt intake reduction is now a global public health challenge [60]. Reducing salt intake has been identified as one of the most cost-effective measures to improve population health outcomes [59]. High sodium intake is a crucial risk factor for chronic diseases, and it has posed a high burden in Japan for decades [8, 10]. The current daily mean salt intake in Japan exceeds public recommendations across all ages and in both sexes. This study shows that it is possible to reduce the Japanese population’s salt intake by up to 2.22 g (21.1%) on average without compromising the taste of food by substituting salt with umami substances, which corresponds to a 22.3% reduction in the average salt intake of the population. In addition to reducing the salt intake among consumers, this study demonstrates that the universal incorporation of umami substances into the some foods can effectively reduce salt intake at the population level.

The previous study, using the data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2013–2016 in the US, focused solely on MSG as a solution for salt reduction [26]. However, global recognition of MSG as an effective and practical solution for salt intake reduction remains a major challenge. In a widely reported study published in 1968, MSG in Chinese food was suggested to be the cause behind numbness and palpitations in the neck and arms and linked to various health problems, known as the Chinese restaurant syndrome [61]. Following this study, several studies also reported the association between MSG and various health effects, including asthma, urticaria, atopic dermatitis, dyspnea, tachycardia, metabolic syndrome, obesity and blood pressure increase [62,63,64,65,66]. However, other studies, including a double-blind placebo-controlled trial, have evaluated the reported reactions to MSG and confirmed a lack of plausible evidence between MSG intake and the development of such symptoms [67,68,69,70]. Furthermore, major scientific committees and regulatory bodies, such as the Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA), the European Commission Scientific Committee on Food (SCF), and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), have assessed the safety of MSG and all separately came to a conclusion that MSG is safe to consume at a normal intake level and there is no evidence linking the use of MSG to long-term medical problems for the general public [71]. The more recent evidence-based safety reviews of MSG also came to the same conclusions, addressing that some studies speculatively linked animal pharmacology to human food use of MSG, and many are based on excessive dosing that does not meet with levels normally consumed in food products [72, 73].

The previous US study focusing solely on MSG reported that the overall salt intake reduction among the population was 7.3% [26]. Meanwhile, reduction of sodium can also be achieved with sodium-free glutamates, such as CDG, inosinate, and guanylate [74]. Accordingly, the scope of our study has been expanded from MSG to the wider range of umami substances. As such, our findings suggested that umami substances could potentially make a greater impact on reducing salt intake than MSG in the previous study. On the other hand, we selected food items that are widely consumed by the Japanese, such as seasoning salt, soy sauce, miso paste, other seasonings, and processed fish. Indeed, soy sauce is one of the most highly consumed food items in Japan, and this study showed the largest impact of daily salt reduction in soy sauce, up to 0.68 g among its consumers and 0.37 g among the total population. On the other hand, cheese, spices and other, beef, margarine, and other confectionery had less impact on reducing salt intake at the population level because they are less consumed in Japan.

To reduce the Japanese population’s daily salt intake, the Japanese government took steps to enforce the new food labelling system and the nutrition labelling system in April 2020 [75, 76]. These systems made it mandatory for food companies to disclose the amount of salt/sodium in their products to ensure that their consumers are aware of the nutritional contents in their foods. However, these measures alone may not be sufficient in addressing the problem because reducing salt intake is not a priority among consumers [77]. Furthermore, reducing the salt in foods may lower the quality of food. For example, a 75% reduction of salt in sausages decreases the sausages' hardness, chewiness, and cohesiveness [52]. Hence, food companies often provide low-sodium alternatives that give their consumers the taste and the quality they seek without the harmful amounts of sodium [78]. Potassium chloride, calcium chloride, and magnesium sulfate are also commonly used as substitutes for table salt. However, their bitter taste has repelled the consumers and resulted in their limited use. In contrast, umami substances, which are naturally present in various foods, are widely accepted by consumers [79]. As umami substances enhance the original flavor in foods, incorporation of umami substances into food items will reduce the salt intake more effectively [18, 80].

The food industry should take action to raise consumer awareness on the benefits of eating low-sodium foods while reducing the salt in their products, so that consumers can adapt to the changes in the taste over time [74]. Accordingly, the food industry's role is essential in reducing the daily salt intake of Japanese population and reducing their health risks [11]. Moreover, reducing salt intake through food science and technological advance is an appropriate method to make the most impactful salt intake reduction at the population level [60]. Our study has provided the essential data on the distribution of the selected food consumers, the market shares of the selected food items with low-sodium alternatives, and its impact on public health by showing the potential salt intake reduction. This information may instruct and inspire the food industry to develop more low-sodium products and distribute them in the market.

This study has some strengths. This is the first study to show the impact of salt reduction by replacing NaCl with umami substances in the selected Japanese food products. The use of the nationally representative data has guaranteed the study's generalisability to the Japanese population. The modelling assumptions of salt reduction were made based on scientific evidence, consultation with food scientists and consideration of market distributions of low-sodium products.

This study is subject to similar limitations found in other studies concerning dietary patterns [81, 82]. First, the dietary data we used in our analysis may have some biases. Because the dietary data from the NHNS were based on the weighted single-day dietary record, the analysis may not have captured the long-term dietary patterns. In dietary surveys, participants' self-reports tend to be associated with social desirability and recall bias. Moreover, reliance on dietary intake records made by household representatives may lead to biased estimates of dietary intake, particularly for those meals taken outside the home. Additionally, NHNS's stratified two-cluster sampling design may have caused selection bias, leading to biased estimates. Second, the data on food-specific salt intake were not publicly available. Therefore, an individual's food-specific salt intake was estimated by regression method which may not have accurately reflected the actual amount of salt intake from each food item. Third, age-specific preferences of food which may affect the potential overall salt reduction were not considered [83]. Fourth, we did not consider possible changes in food intake as a result of umami substance incorporation to reduce salt intake. Umami flavour may increase overall food intake or decrease vegetable intake as the previous studies suggested that vegetable intake is associated with salt intake [84,85,86]. The changes in food intake could change the effects of umami substances on salt intake reduction. Fifth, we did not include the low-sodium products using sodium replacers, other than umami substances, such as potassium chloride, mineral salts and yeast extracts in Japan [87,88,89] in our modelling, as we assessed the effects of umami substances on salt intake reduction. Thus, we may have underestimated the market share of low-sodium products. Finally, we did not consider the Japanese population’s current MSG intake and its association with health outcomes due to unavailability of data. Hence, caution is needed when the salt intake reduction is pursued by using MSG which may cause the long-term health effects on the population.

Conclusions

Our study has suggested that the incorporation of umami substances into the selected food items could potentially reduce the average daily salt intake of the Japanese population by 22.3%, which is equivalent to 2.22 g of daily salt reduction. The universal incorporation of umami substances into the selected food items might enable the Japanese to achieve the national dietary goals. However, the level of salt intake reduction still falls short of 5.0 g/day recommended by WHO. Along with the public health efforts, collaboration with experts in food science should be pursued. Further investigation, innovation, and distribution of low-sodium food products are needed to help reduce the adult Japanese population's salt intake and consequently reduce their chances of developing NCDs.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from MHLW, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data. The data were used with an approval from MHLW to be utilized for the current study without making it publicly available. Further information on application and use of data can be obtained by contacting the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- CDG:

-

Calcium diglutamate

- CVDs:

-

Cardiovascular diseases

- DRIs:

-

Dietary Reference Intakes

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- GBD:

-

Global Burden of Disease

- JECFA:

-

Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives

- MHLW:

-

Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare

- MSG:

-

Monosodium glutamates

- NaCl:

-

Sodium chloride

- NCDs:

-

Non-communicable diseases

- NHNS:

-

National Health and Nutrition Survey

- NNS:

-

National Nutrition Survey

- SCF:

-

European Commission Scientific Committee on Food

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- US:

-

Unites States

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

IHME: The Lancet: latest global disease estimates reveal perfect storm of rising chronic diseases and public health failures fuelling COVID-19 pandemic. http://www.healthdata.org/news-release/lancet-latest-global-disease-estimates-reveal-perfect-storm-rising-chronic-diseases-and (2020). Accessed 31 Aug 2022.

WHO. NCD Global Monitoring Framework. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

Santos JA, Tekle D, Rosewarne E, Flexner N, Cobb L, Al-Jawaldeh A, et al. A Systematic Review of Salt Reduction Initiatives Around the World: A Midterm Evaluation of Progress Towards the 2025 Global Non-Communicable Diseases Salt Reduction Target. Adv Nutr. 2021;12:1768–80.

Santos JA, Sparks E, Thout SR, McKenzie B, Trieu K, Hoek A, et al. The Science of Salt: A global review on changes in sodium levels in foods. J Clin Hypertens. 2019;21:1043–56.

Ding J, Sun Y, Li Y, He J, Sinclair H, Du W, et al. Systematic Review on International Salt Reduction Policy in Restaurants. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:9570.

Bhat S, Marklund M, Henry ME, Appel LJ, Croft KD, Neal B, et al. A Systematic Review of the Sources of Dietary Salt Around the World. Adv Nutr. 2020;11:677–86.

Initiatives Development. Global Nutrition Report: Action on equity to end malnutrition. Bristol: Development Initiatives; 2020.

GBD 2019 Risk Factors Collaborators. Global burden of 87 risk factors in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1223–49.

GBD 2019 Demographics Collaborators. Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950–2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1160–203.

Nomura S, Sakamoto H, Glenn S, Tsugawa Y, Abe SK, Rahman MM, et al. Population health and regional variations of disease burden in Japan, 1990–2015: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;390:1521–38.

Miura K, Ando K, Tsuchihashi T, Yoshita K, Watanabe Y, Kawarazaki H, et al. Report of the Salt Reduction Committee of the Japanese Society of Hypertension(2) Goal and strategies of dietary salt reduction in the management of hypertension [Scientific Statement]. Hypertens. 2013;36:1020–5.

Tsugane S. Why has Japan become the world’s most long-lived country: insights from a food and nutrition perspective. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2021;75:921–8.

Powles J, Fahimi S, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Shi P, Ezzati M, et al. Global, regional and national sodium intakes in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis of 24 h urinary sodium excretion and dietary surveys worldwide. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e003733.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare Japan. A basic direction for comprehensive implementation of National Health Promotion. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Japan; 2012.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare Japan. Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2020.

Ministry of Health Labour and Welfare Japan. The National Health and Nutrition Survey in Japan, 2016. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2017.

Nomura S, Yoneoka D, Tanaka S, Ishizuka A, Ueda P, Nakamura K, et al. Forecasting disability-adjusted life years for chronic diseases: reference and alternative scenarios of salt intake for 2017–2040 in Japan. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1475.

Henney JE, Taylor CL, Boon CS, editors. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. Washington DC: The National Academies Press; 2010.

Beauchamp GK. Sensory and receptor responses to umami: an overview of pioneering work. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;90:723S-727S.

Mueller E, Koehler P, Scherf KA. Applicability of salt reduction strategies in pizza crust. Food Chem. 2016;192:1116–23.

Yamaguchi S, Takahashi C. Interactions of Monosodium Glutamate and Sodium Chloride on Saltiness and Palatability of a Clear Soup. J Food Sci. 1984;49:82–5.

Nishimura T, Goto S, Miura K, Takakura Y, Egusa AS, Wakabayashi H. Umami compounds enhance the intensity of retronasal sensation of aromas from model chicken soups. Food Chem. 2016;196:577–83.

Buechler AE, Lee SY. Drivers of liking for reduced sodium potato chips and puffed rice. J Food Sci. 2020;85:173–81.

Kongstad S, Giacalone D. Consumer perception of salt-reduced potato chips: Sensory strategies, effect of labeling and individual health orientation. Food Qual Prefer. 2020;81:103856.

Wang S, Tonnis BD, Wang ML, Zhang S, Adhikari K. Investigation of Monosodium Glutamate Alternatives for Content of Umami Substances and Their Enhancement Effects in Chicken Soup Compared to Monosodium Glutamate. J Food Sci. 2019;84:3275–83.

Wallace TC, Cowan AE, Bailey RL. Current Sodium Intakes in the United States and the Modelling of Glutamate’s Incorporation into Select Savory Products. Nutrients. 2019;11:2691.

Anderson CA, Appel LJ, Okuda N, Brown IJ, Chan Q, Zhao L, et al. Dietary sources of sodium in China, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States, women and men aged 40 to 59 years: the INTERMAP study. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110:736–45.

Ikeda N, Takimoto H, Imai S, Miyachi M, Nishi N. Data Resource Profile: The Japan National Health and Nutrition Survey (NHNS). Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44:1842–9.

Office for Resources Policy Division Science and Tethnology Policy Bureau Japan. Standards tables of food composition in Japan ― 2015 (seventh revised edition). https://www.mext.go.jp/en/policy/science_technology/policy/title01/detail01/sdetail01/sdetail01/1385122.htm (2015). Accessed 31 Aug 2022.

Fuji Keizai Management Co., Ltd. Future outlook for the wellness food market 2019. Tokyo: Fuji Keizai Management Co., Ltd. Japan; 2019.

Takagaki H. Low-salt composition. Japan patent JPA01-304860. Japan; 1989.

Ninomiya K. Nutrition-fortified low-sodium food. Japan patent JPA58-198269. Japan; 1983.

Kao Corporation. Liquid seasoning. Japan patent JPA2006-141226. Japan; 2006.

Ishida M, Tezuka H, Hasegawa T, Cao L, Imada T, Kimura E, et al. Sensory evaluation of a low-salt menu created with umami, similar to savory, substance. Nippon Eiyo Shokuryo Gakkaishi. 2011;64:305–11.

Kameda seika Co., Ltd. Low-salt, low-protein, low-phosphorus, low-potassium soy sauce-like seasoning. Japan patent JPA09-275930. Japan; 1997.

Yamasa Corporation. Low-salt bean miso with excellent taste. Japan patent JPA5523618. Japan; 2014.

Chi SP, Chen TC. Predicting optimum monosodium glutamate and sodium chloride concentrations in chicken broth as affected by spice addition. J Food Process. 1992;16:313–26.

Manabe M. Saltiness Enhancement by the Characteristic Flavor of Dried Bonito Stock. J of Food Sci. 2008;73:S321–5.

Goh FXW, Itohiya Y, Shimojo R, Sato T, Hasegawa K, Leong LP. Using naturally brewed soy sauce to reduce salt in selected foods. J Sens Stud. 2011;26:429–35.

Huynh HL, Danhi R, Yan SW. Using Fish Sauce as a Substitute for Sodium Chloride in Culinary Sauces and Effects on Sensory Properties. J Food Sci. 2016;81:S150-155.

Kremer S, Mojet J, Shimojo R. Salt Reduction in Foods Using Naturally Brewed Soy Sauce. J Food Sci. 2009;74:S255–62.

Ogasawara Y, Mochimaru S, Ueda R, Ban M, Kabuto S, Abe K. Preparation of an Aroma Fraction from Dried Bonito by Steam Distillation and Its Effect on Modification of Salty and Umami Taste Qualities. J Food Sci. 2016;81:C308–16.

Leong J, Kasamatsu C, Ong E, Hoi JT, Loong MN. A study on sensory properties of sodium reduction and replacement in Asian food using difference-from – control test. Food Sci Nutr. 2015;4:469–78.

Jinap S, Hajeb P, Karim R, Norliana S, Yibadatihan S, Abdul-Kadir R. Reduction of sodium content in spicy soups using monosodium glutamate. Food Nutr Res. 2016;60:30463.

Carter BE, Monsivais P, Drewnowski A. The sensory optimum of chicken broths supplemented with calcium di-glutamate: A possibility for reducing sodium while maintaining taste. Food Qual Prefer. 2011;22:699–703.

Ball P, Woodward D, Beard T, Shoobridge A, Ferrier M. Calcium diglutamate improves taste characteristics of lower-salt soup. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:519–23.

Roininen K, Lähteenmäki L, Tuorilla H. Effect of umami taste on pleasantness of low-salt soups during repeated testing. Physiol Behav. 1996;60:953–8.

Rodrigues JF, Junqueira G, Gonçalves CS, Carneiro JD, Pinheiro AC, Nunes CA. Elaboration of garlic and salt spice with reduced sodium intake. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2014;86:2065–75.

Ichikawa Chemical Institution. Low-salted processed meat. Japan patent JPA59-118038. Japan; 1984.

Quadros DAd, Rocha IFdO, Ferreira SMR, Bolini HMA. Low-sodium fish burgers: Sensory profile and drivers of liking. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2015;63:236–42.

Woodward DR, Lewis PA, Ball PJ, Beard TC. Calcium glutamate enhances acceptability of reduced-salt sausages. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2003;12:S35.

dos Santos BA, Campagnol PCB, Morgano MA, Pollonio MAR. Monosodium glutamate, disodium inosinate, disodium guanylate, lysine and taurine improve the sensory quality of fermented cooked sausages with 50% and 75% replacement of NaCl with KCl. Meat Sci. 2014;96:509–13.

Myrdal Miller A, Mills K, Wong T, Drescher G, Lee SM, Sirimuangmoon C, et al. Flavor-enhancing properties of mushrooms in meat-based dishes in which sodium has been reduced and meat has been partially substituted with mushrooms. J Food Sci. 2014;79:S1795-1804.

Tampei Pahrmaceutical Co., Ltd. Low sodium instant pickles. Japan patent JPA60-153751. Japan; 1985.

Rodrigues JF, Goncalves CS, Pereira RC, Carneiro JD, Pinheiro AC. Utilization of temporal dominance of sensations and time intensity methodology for development of low-sodium Mozzarella cheese using a mixture of salts. J Dairy Sci. 2014;97:4733–44.

da Silva TLT, de Souza VR, Pinheiro ACM, Nunes CA, Freire TVM. Equivalence salting and temporal dominance of sensations analysis for different sodium chloride substitutes in cream cheese. Int J Dairy Technol. 2014;67:31–8.

de Souza VR, Freire TVM, Saraiva CG, de Deus Souza Carneiro J, Pinheiro ACM, Nunes CA. Salt equivalence and temporal dominance of sensations of different sodium chloride substitutes in butter. J Dairy Res. 2013;80:319–25.

Goncalves C, Rodorigues J, Junior H, Carneiro J, Freire T, Freire L. Sodium reduction in margarine using NaCl substitutes. An Acad Bras Cienc. 2017;89:2505–13.

WHO. Guideline: Sodium intake for adults and children. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

Brown IJ, Tzoulaki I, Candeias V, Elliott P. Salt intakes around the world: implications for public health. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:791–813.

Schaumburg H. Chinese-restaurant syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1968;278:1122.

Gann D. Ventricular tachycardia in a patient with the “Chinese restaurant syndrome.” South Med J. 1977;70:879–81.

Ratner D, Eshel E, Shoshani E. Adverse effects of monosodium glutamate: a diagnostic problem. Isr J Med Sci. 1984;20:252–3.

He K, Zhao L, Daviglus ML, Dyer AR, Horn LV, Garside D, et al. Association of monosodium glutamate intake with overweight in Chinese adults: the INTERMAP Study. Obesity. 2008;16:1875–80.

Insawang T, Selmi C, Cha’on U, Pethlert S, Yongvanit P, Areejitranusorn P, et al. Monosodium glutamate (MSG) intake is associated with the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in a rural Thai population. Nutr. 2012;9:1–6.

Shi Z, Yuan B, Taylor AW, Dai Y, Pan X, Gill TK, et al. Monosodium glutamate is related to a higher increase in blood pressure over 5 years: findings from the Jiangsu Nutrition Study of Chinese adults. J Hypertens. 2011;29:846–53.

Geha RS, Beiser A, Ren C, Patterson R, Greenberger PA, Grammer LC, et al. Multicenter, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multiple-challenge evaluation of reported reactions to monosodium glutamate. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106:973–80.

Brosnan JT, Drewnowski A, Friedman MI. Is there a relationship between dietary MSG and [corrected] obesity in animals or humans? Amino Acids. 2014;46:2075–87.

Nakamura H, Kawamata Y, Kuwahara T, Smriga M, Sakai R. Long-term ingestion of monosodium L-glutamate did not induce obesity, dyslipidemia or insulin resistance: a two-generation study in mice. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol. 2013;59:129–35.

Williams AN, Woessner KM. Monosodium glutamate “allergy”: menace or myth? Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:640–6.

Walker R, Lupien JR. The safety evaluation of monosodium glutamate. J Nutr. 2000;130:1049s–52s.

Zanfirescu A, Ungurianu A, Tsatsakis AM, Nițulescu GM, Kouretas D, Veskoukis A, et al. A review of the alleged health hazards of monosodium glutamate. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2019;18:1111–34.

NonyeHenry-Unaeze H. Update on food safety of monosodium l-glutamate (MSG). Pathophysiology. 2017;24:243–9.

WHO. Salt reduction. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020.

Okuda N, Nishi N, Ishikawa-Takata K, Yoshimura E, Horie S, Nakanishi T, et al. Understanding of sodium content labeled on food packages by Japanese people. Hypertens. 2014;37:467–71.

Okada C, Takimoto H. Development of a screening method for determining sodium intake based on the Dietary Reference Intakes for Japanese, 2020: A cross-sectional analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Survey. Japan PloS One. 2020;15:e0235749–e0235749.

The LM, Conundrum S. Evolving Recommendations and Implications. Nutr. 2019;54:31–41.

Hoppu U, Hopia A, Pohjanheimo T, Rotola-Pukkila M, Mäkinen S, Pihlanto A, et al. Effect of Salt Reduction on Consumer Acceptance and Sensory Quality of Food. Foods. 2017;6:103.

Ninomiya K. Science of umami taste: adaptation to gastronomic culture. Flavour. 2015;4:13.

Prescott J. Effects of added glutamate on liking for novel food flavors. Appetite. 2004;42:143–50.

Kurotani K, Akter S, Kashino I, Goto A, Mizoue T, Noda M, et al. Quality of diet and mortality among Japanese men and women: Japan Public Health Center based prospective study. BMJ. 2016;352:i1209.

Oba S, Nagata C, Nakamura K, Fujii K, Kawachi T, Takatsuka N, et al. Diet based on the Japanese Food Guide Spinning Top and subsequent mortality among men and women in a general Japanese population. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109:1540–7.

Koga M, Fujii M. Sodium intake from seasonings by dish category and age group: An analysis of the 2014 Yamanashi Prefecture Nutrition Survey results. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 2021;68:320–30.

Ahern SM, Caton SJ, Bouhlal S, Hausner H, Olsen A, Nicklaus S, et al. Eating a Rainbow. Introducing vegetables in the first years of life in 3 European countries. Appetite. 2013;71:48–56.

Feng Y, Tapia MA, Okada K, Lazo NBC, Chapman-Novakofski K, Phillips C, et al. Consumer Acceptance Comparison between Seasoned and Unseasoned Vegetables. J Food Sci. 2018;83:446–53.

Nomura S, Ishizuka A, Tanaka S, Yoneoka D, Uneyama H, Shibuya K. Umami: an alternative Japanese approach to reducing sodium while enhancing taste desirability. Health. 2021;13:629–36.

Tsuchihashi T. Dietary salt intake in Japan - past, present, and future. Hypertens. 2022;45:748–57.

Kawasaki T, Itoh K, Kawasaki M. Reduction in blood pressure with a sodium-reduced, potassium- and magnesium-enriched mineral salt in subjects with mild essential hypertension. Hypertens. 1998;21:235–43.

Vidal VAS, Santana JB, Paglarini CS, da Silva MAAP, Freitas MQ, Esmerino EA, et al. Adding lysine and yeast extract improves sensory properties of low sodium salted meat. Meat Sci. 2020;159:1–9.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This article was partially supported by a joint research grant from Ajinomoto Co., Inc. H.U. is employed by the commercial founder, Ajinomoto Co., Inc. The commercial funder provided support in the form of salaries for H.U. but did not have any additional role in the decision to publish or the preparation of this manuscript. This article was also partly funded by a research grant from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (19H01074).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.N. and K.S. led the study. All authors conceived and designed the study. S.T., D.Y., and S.N. took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. S.T., D.Y., and S.N. acquired the data. S.T., D.Y., and S.N. analysed and interpreted the data. S.T. and D.Y. conducted the statistical analysis. S.T., D.Y., A.I. and S.N. drafted the article. All authors made critical revisions to the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the manuscript. The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this paper are those of the authors and are independent of the funding bodies.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Committee of the Graduate School of Medicine, The University of Tokyo approved this study (authorization number 11964) and waived the need for informed consent as this study was a secondary analysis of anonymised data that is collected routinely by the MHLW. This study was conducted according to the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

S.N. and K.S. report a grant from the Ajinomoto Co., Inc. H.U. declares that he is employed by Ajinomoto Co., Inc. and has no other competing interests. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, S., Yoneoka, D., Ishizuka, A. et al. Modelling of salt intake reduction by incorporation of umami substances into Japanese foods: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 23, 516 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15322-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15322-6