Abstract

Background

Previous studies, predominantly in Western individuals, have reported weight gain or weight loss are related to the increased depressive symptoms at all ages, but no study of depressive symptoms has examined its relation to actual (not just self-reported) weight changes in the middle-aged and older adults. Evidence of the relationship in older Asian individuals remains sparse. The study aimed to examine the relationship between weight changes and incidence of depressive symptoms in a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling older Asians.

Method

Data were obtained from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), which included 17,284 adults aged 45 years. Participants were followed every two years using a face-to-face, computer-aided personal interview (CAPI) and structured questionnaire. We excluded participants with no follow-up data. The numbers of individuals who completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys were 3118 for the short-term (two years from 2011–2013) and the long-term (four years from 2011–2015). Additionally, to associate weight change with subsequent depressive symptoms, we also included 2472 participants without depressive symptom in 2013 and observed the incidence of depressive symptom in 2015 (subsequent term from 2013–2015). Finally, weight changes were classified as loss > -3%, stable-3–3%, gain3-6%, gain6-9%, and gain > 9%. Multivariable-adjusted cox regression in the study were used to assess the hazard ratios (HRs) of each weight change category.

Results

The incidence of depressive symptoms was 20.72% in the 2011–2013, 27.04% in the 2011–2015, and 23.02% in 2013–2015. Weight loss > 3% for all intervals was associated with higher depressive symptoms than stable weight during the 2011–2013 [1.305(1.031,1.651)] among the total populations. When stratified by sex, the results in males and females were different from those in the total population [females:1.389(0.997, 1.935); males:1.263(0.902, 1.767)]. Weight loss > 3% for intervals was associated with higher depressive symptoms than stable weight during the 2013–2015[1.643(1.140, 2.368)] among the males and its effect was also stronger for the total in 2011–2013. Moreover, there was no significant association between weight gain and incident depressive symptom, and no significant interaction effect in terms of the sex*weight changes.

Conclusion

Our findings could inform health promotion interventions to body-weight management aimed at improving the health of the middle-aged and older adults, particularly in the total people with short-term weight loss and males with subsequent term weight loss.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The depressive symptom is a common psychological disorder condition that represents a serious burden worldwide. Approximately 322 million people worldwide suffer from depressive symptom [1]. Weight change over the course of several years is often a good predictor of depressive symptom in adolescence [2] and adult [3]. It has been shown to predict the incidence of depressive symptom better than a single weight assessment, particularly in old age [4,5,6]. However, previous studies findings on the association between weight change and depressive symptom have been inconsistent. Moreover, the effect of weight change on depressive symptom can be influenced by several factors such as demographic characteristics, living habits, health status, and baseline body mass index.

A recent meta-analysis [7] conducted with 53 studies including 12 cohort studies and 41 cross-sectional studies showed that underweight and obesity increased the risk of depression, and the relationship between overweight and depression differed by sex. Furthermore, the cohort studies showed a significant increase overall hazard ratios (HRs) of depression in underweight, while those showed no statistically significant relationship with depression in overweight. In subgroup analyses, it was found different results according to sex (men: HR = 0.84, 95%CI 0.72–0.97, women: HR = 1.16, 95%CI 1.01–1.25). In cross-sectional studies, obesity with BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 (OR = 1.18, 95%CI 1.11–1.26) showed a greater pooled odds ratio (OR) than obesity with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2(OR = 1.59, 95%CI 1.12–2.24). Although the meta-analysis included cohort studies and cross-sectional studies and highlighted the potential adverse effect of weight change on depression, particularly weight loss, no considerations of the weight change over the course of several years in different studies were made.

In addition, the other meta-analysis performed for the 15 studies by Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, et al. [8] found that obesity increased the risk of depression among Americans and Europeans, yet the meta-analysis only included Western participants, and no considerations of other ethnicities, such as Asians. Moreover, there was no analysis focusing on underweight participants. It was uncertain whether underweight affects depression in nationwide cohort participants or whether obesity was associated with depression. Thus, further studies among the middle-aged and older adults in Asian nations are needed to identify whether the relationship between weight change and incidence of depression in Asian participants differs from that observed in Western participants.

To address these gaps, we used four years of longitudinal data from the nationally representative sample of community-dwelling Chinese participants aged45 years and explored to examine the relationship between weight changes, including loss and gain, and incidence of depressive symptom during short–term (two years), long-term (four years), and subsequent term (two years) internals. Furthermore, our study explores the stability of the association between weight changes and depressive symptom by sex on Asians.

Materials and methods

Study participants

We obtained the data from The China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS). The CHARLS began in 2011 with a cohort of 17,284 participants ≥ 45 years (Wave1). Subsequently, data collection was conducted in 2013(Waves2), 2015(Waves3), and 2018(Wave4). CHARLS was a nationally representative longitudinal survey of the mid-aged and older adults in China along with their spouses. The respondents will be followed every two years using a face-to-face, computer-aided personal interview (CAPI) and structured questionnaire. The current study used data from participants who participated in Wave1, Waves2, and Waves3. We excluded individual who met any of the following criteria at baseline (1) CESD-10 scores 10, (2) no BMI data, (3) no age/sex/educational levels/marital status/smoking status/alcohol consumption/exercise/diseases/live place/activities data. In addition, we excluded participants with no follow-up data. The numbers of individuals who completed both the baseline and follow-up surveys were 3118 for the short-term (2011–2013) and the long-term (2011–2015). Additionally, to associate weight change with subsequent depressive symptoms [associate the weight changes between 2011 and 2013 (exposure) with development of depression between 2013 and 2015(outcome)], we also included 2472 participants without depressive symptom in 2013 and observed the incidence of depressive symptom in 2015 (subsequent term 2013–2015). Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study individuals, follow-up, and lost to follow-up.

Definition of depressive symptom

Based on the Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D), we used CES-D to define depressive symptom. It consists of 10 items, the total score ranges from 0 to 30, with a higher total score indicating more severe depressive symptoms. We used harmonized criteria cutoff values (total scores ≥ 10) to define depressive symptom. In our study, the Cronbach alpha coefficient was 0.86 and the construct validity was 0.62 [9, 10]. The Chinese version of the CES-D has shown good reliability and validity in the middle-aged and older adults.

Weight changes

Height was measured by the vertical height meter, and weight was measured with a digital weight scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared in our study. We used three weight changes indicators according to the interval over which the changes were assessed: short-term (two years from 2011 to 2013), long-term (four years from 2011 to 2015) and subsequent term (two years from 2013 to 2015). The percentages of weight changes between the baseline and the follow-up surveys, based on the baseline body mass index, was calculated. We classified the percentages of weight changes into five categories [4]: loss > -3%, stable-3–3%, gain3-6%, gain6-9%, and gain > 9%.

Covariates

Covariates included age, sex, education, marital status, current residence, smoking status, alcohol consumption, exercise, diseases, activities at baseline, and entry wave (Wave 1, 2, 3) were incorporated as covariates in our study. Age was categorized into four groups: 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, and ≥ 75 years old. Sex was classified into two categories: male and female. Education was defined as illiterate, or less than elementary school, or high school, or above vocational school. Marital status was defined as the married or the single (divorced, and never married, widowed, or separated). Current residence was categorized into the rural and urban. Smoking status was defined as never smoker or former-smoker or current smoker. Alcohol consumption was categorized into the never drinker, less than once a month drinker, and more than once a month drinker. Exercise was categorized three groups: no exercise, less than regular exercises, and regular exercises. Taking activities including (1) communicating with friends or providing help to neighbors, friends, or family, or (2) doing a sport, social, or other kind of club or playing Ma-jong, or (3) playing played cards, chess, or going to community club, or (4) taking part in a community-related organization, or (5) doing voluntary or charity work, or (6)caring for a sick or disabled adult, or (7) attending an educational or training course, or (8) stock investment, or (9)using the Internet were dichotomized as ever (at least once a month) or never. Diseases included (1) cancer or malignant tumor, (2) dyslipidemia, (3) hypertension, (4) chronic lung diseases, (5) diabetes or high blood sugar, (6) liver disease, (7) kidney disease, (8) asthma were reported by the respondents, (9) arthritis or rheumatism, (10) stomach or other digestive disease, (11) heart attack, coronary heart disease, angina, congestive heart failure, or other heart problems, (12) emotional, nervous, or psychiatric problems, (13) memory-related disease, (14) stroke. According to our previous standard [5], a continuous variable was used to reflect presence of chronic health conditions which ranged from 0 to 14. Numbers of the diseases condition were classified into three categories: 0, 1–2, and 3–14. The categories have been widely used in our studies [11,12,13,14,15,16].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version21.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages and compared using the 2 test. Multivariable-adjusted cox regression was conducted using the hazard ratio (HR), and 95% confidence interval (CI) for the association of body mass index (BMI) changes categories with the incident depressive symptom. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

3118 participants who completed the questionnaires effectively were included in the short-term (2011–2013) and the long-term (2011–2015). 2472 participants without depressive symptom were included in 2013(2013–2015). The characteristics of the study participants were shown in Table 1. At baseline, 54.49% of the participants were males in the 2011–2013 and 2011–2015, and 56.59% was males in the 2013–2015. The mean age was 59.15 years (standard deviation [SD] = 8.50) in the 2011–2013 and 2011–2015, and was 60.12 years (standard deviation [SD] = 8.66) in the 2013–2015. The mean BMI was 23.80 kg/m2 (standard deviation [SD] = 3.85) in the 2011–2013 and 2011–2015, and 24.15 kg/m2 (standard deviation [SD] = 3.60) in the 2013–2015.

Baseline characteristics classified according to subsequent onset of depressive symptoms were illustrated in Table 2. Participants who developed depressive symptoms were more likely to be female, to have lower educational levels, and be never drinking in the three different sets. They tended to take activities, live in rural, and have 0–2 diseases in the 2011–2013 and 2011–2015. Additionally, they also tended to be never smoking in the 2011–2015 and 2013–2015.

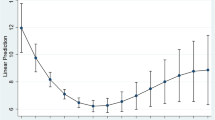

The association between weight changes and incidences of depressive symptoms by baseline BMI were shown in Table 3. Firstly, depressive symptoms risk was increased for BMI loss > 3% during the 2011–2013 [1.329(1.053,1.676)] among the total people. After adjusting for age, educational levels, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, exercise, diseases, live place, and activities, similar results were found in the total population [1.305(1.031,1.651)]. Secondly, depressive symptoms risk was increased for BMI lost > 3% during 2013–2015[1.654(1.153,2.373)] among males, and its effect was stronger for the 2011–2013. After adjusting for age, sex, educational levels, marital status, smoking status, alcohol consumption, exercise, diseases, live place, and activities, depressive symptoms risk was also increased for BMI lost > 3% during the 2013–2015[1.643(1.140,2.368)], and its effect was also stronger than the 2011–2013. Lastly, there was no significant association between weight gain and incident depressive symptom, and no significant interaction effect in terms of the sex*weight changes.

Discussion

Previous studies have reported differences in the relationship between weight change and the incidence of depressive symptom. Further, the results in the association among the mid-aged and older adults in China have been sparse. Our study used a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling mid and older adults followed for up to four years and explored the relationship between weight change and incidence of depressive symptom with an improved methodology.

The analyses were limited to participants who attended both the 2-year and the 4-year follow-up session, and 3118 individuals for the short-term (2011–2013) and the long-term (2011–2015) were included. We found that weight loss of > -3% during short-term was related to an increased risk of incidence of depressive symptom among total participants. However, this was not completely observed in the subgroup analysis by sex. The reason may be that the statistical power was lower in sex-stratified analyses. Additionally, we have failed to find the associations between weight changes and the incidence of depressive symptom in others subgroups, especially the weight gain groups. Furthermore, in order to associate weight change with subsequent depressive symptoms [associate the weight changes between 2011 and 2013 (exposure) with development of depression between 2013 and 2015(outcome)], we also included 2472 participants without depressive symptom in 2013 and observed the incidence of depressive symptom in 2015 (subsequent term 2013–2015). It was suggested that depressive symptoms risk was increased for BMI loss > 3% during the 2013–2015 among males. However, it was found that weight gain was not associated with the incident depressive symptom. Several clinical trials [17,18,19] found that unhealthy weight control targeting weight loss increased depression incidence in participants. These associations can be explained, in part, by mental stress triggered by unsuccessful weight control. As weight is considered as an individual and controllable responsibility, difficulty weight loss may be misattributed to personal failure rather than the behavioral weight-loss interventions. Societal pressures with respect to slender body can also moderate associations between weight loss and depressive symptom [20, 21]. Moreover, evidences [22, 23] have supported relative associations of overvaluation, body dissatisfaction, disordered, eating and preoccupation with psychological distress and eating disorder behaviors. In the meta-analysis [7], it has been reported that underweight at baseline increased the risk of incidence depression [1.16(1.08–1.24)]. In contrast to a large number of studies [24,25,26,27,28,29] that focused on the mechanisms that underlie the relationship between body mass index and depression, there are relatively few studies that investigated the association between weight change and the incidence of depression. Previous studies [30,31,32] reported that people who were may have low self-esteem. Low self-esteem may portray them as helpless and incapable to cope with the world, and lead to depression [33,34,35,36,37]. In modern society, being underweight may express a poor body image and increase the incidence of depression in males. However, underweight people also increased the incidence of depressive symptom in our study (the 2011–2013 among the total and 2013–2015 among males), and there may be due to leptin in the association during those terms. Leptin [38] can influence the relationship between body weight and depressive symptom. Leptin levels are decreased in participants with low body mass index. In addition, leptin is regarded as an effective antidepressant, and there is a significant correlation between low leptin levels and depressive symptoms [39]. Though several studies [40,41,42,43,44] have found that obesity increased the risk of depression and the result is consistent with meta-analysis [7, 8]. However, Goes VF, Wazlawik E, D'Orsi E, et al. [45] conducted a population-based cohort study including 1,702 older adults in Southern Brazil evaluated between 2009/10 and 2013/14 and found that older adults with obesity had a higher prevalence odds ratio of being depressed than individuals with normal weight while overweight individuals had no significant association with incident depression. The different results reflect that the association between weight and the incidence of depressive symptom may be influenced by the cultural background and related social pressures. Partial results in our study were not in accord with the results of other studies, but those provided insight into associations between weight changes and the incidence of depressive symptom during different terms in the middle-aged and older adults.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study has several strengths. First, the weight change was measured by BMI, and the BMI was calculated by the body weight and height which was measured by vertical height meter and digital weight scale when it was objectively measured. Second, the study was based on a nationwide cohort survey, which included participants aged 45 years. Third, it compared the effect of weight changes across two different intervals on the depressive symptom. Previous studies used only set single interval to identify the relationship between weight changes and depressive symptom. It helped us to understand the short- and long-term effects of weight change on the incidence of depressive symptom. At last, we conducted the analysis according to sex, which allowed us to identify sex-specific patterns of relationship between weight change and depressive symptom, and we separately assessed depressive symptom which was related with the loss (> -3%) and gain (3–6%, 6–9%, > 9%) groups. This analysis based on different weight changes provided evidence that the association between weight change and depressive symptom may depend on the sex- and term- patterns in Asia.

Several limitations in our study should be noted. Firstly, the depressive symptom was self-reported in the three waves, when it was subjectively measured. This may have a reporting bias. It is known that people tend to underreport their mental illness in the research. Secondly, we did not consider body composition which was associated with depression [22,23,24] in several studies. More research should investigate the relationship using indicators of body composition to more fully understand the potential mechanisms linking to weight changes over different time ranges to the incidence of depressive symptom. Thirdly, statistical power was lower in sex-stratified analyses. Fourthly, it was aimed to examine the relationship between weight changes and incidence of depressive symptoms. This will help us to explore the relationship between the depressive symptom and incidence of the weight changes in the next step. Finally, although we have fully adjusted the potential confounders, there was still a chance of residual confounders in the study.

Conclusions

Our study using a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling older Chinese participants found that weight loss > 3% for intervals was associated with higher depressive symptoms than stable weight during the 2011–2013 [1.329(1.053,1.676)] among the total populations and the 2013–2015[1.643(1.140,2.368)] among the males. Moreover, there was no significant association between weight gain and incident depressive symptom. The result highlights the importance of health promotion interventions to body-weight management aimed at improving the health of older adults, particularly in the total people with short-term weight loss and males with subsequent term weight loss.

Availability of data and materials

Data can be accessed via http://opendata.pku.edu.cn/dataverse/CHARLS.

Abbreviations

- CHARLS:

-

China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study

- CAPI:

-

Computer-aided personal interview

- HRs:

-

Hazard ratios

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- M:

-

Mean

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- CIs:

-

Confidence intervals

- CESD:

-

Chinese version of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale

- NSFC:

-

The National Natural Science Foundation of China

- NIA:

-

National Institute on Aging

- WB:

-

World Bank

References

Toenders YJ, Schmaal L, Harrison BJ, Dinga R, Berk M, Davey CG. Neurovegetative symptom subtypes in young people with major depressive disorder and their structural brain correlates. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1):108.

Felton J, Cole DA, Tilghman-Osborne C, Maxwell MA. The relation of weight change to depressive symptoms in adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2010;22(1):205–16.

DiPietro L, Anda RF, Williamson DF, Stunkard AJ. Depressive symptoms and weight change in a national cohort of adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1992;16(10):745–53.

Roberts RE, Deleger S, Strawbridge WJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective association between obesity and depression: evidence from the Alameda County Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(4):514–21.

Sachs-Ericsson N, Burns AB, Gordon KH, Eckel LA, Wonderlich SA, Crosby RD, Blazer DG. Body mass index and depressive symptoms in older adults: the moderating roles of race, sex, and socioeconomic status. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(9):815–25.

Vogelzangs N, Kritchevsky SB, Beekman AT, Newman AB, Satterfield S, Simonsick EM, Yaffe K, Harris TB, Penninx BW. Depressive symptoms and change in abdominal obesity in older persons. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(12):1386–93.

Jung SJ, Woo HT, Cho S, Park K, Jeong S, Lee YJ, Kang D, Shin A. Association between body size, weight change and depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2017;211(1):14–21.

Luppino FS, de Wit LM, Bouvy PF, Stijnen T, Cuijpers P, Penninx BW, Zitman FG. Overweight, obesity, and depression: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(3):220–9.

Zhang L, Liu K, Li H, Li D, Chen Z, Zhang LL, Guo LL. Relationship between body mass index and depressive symptoms: the “fat and jolly” hypothesis for the middle-aged and elderly in China. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):1201.

Liu H, Yang X, Guo LL, Li JL, Xu G, Lei Y, Li X, Sun L, Yang L, Yuan T, et al. Frailty and Incident Depressive Symptoms During Short- and Long-Term Follow-Up Period in the Middle-Aged and Elderly: Findings From the Chinese Nationwide Cohort Study. Front Psych. 2022;13: 848849.

Zhang L, Li JL, Guo LL, Li H, Li D, Xu G. The interaction between serum uric acid and triglycerides level on blood pressure in middle-aged and elderly individuals in China: result from a large national cohort study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20(1):174.

Zhang L, Li JL, Zhang LL, Guo LL, Li H, Li D. Association and interaction analysis of body mass index and Triglycerides level with blood pressure in elderly individuals in China Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:8934534.

Zhang L, Li JL, Zhang LL, Guo LL, Li H, Li D. No association between C-reactive protein and depressive symptoms among the middle-aged and elderly in China: Evidence from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. Medicine. 2018;97(38): e12352.

Zhang L, Li JL, Zhang LL, Guo LL, Li H, Li D. Body mass index and serum uric acid level: Individual and combined effects on blood pressure in middle-aged and older individuals in China. Medicine. 2020;99(9): e19418.

Zhang L, Li JL, Zhang LL, Guo LL, Li H, Yan W, Li D. Relationship between adiposity parameters and cognition: the “fat and jolly” hypothesis in middle-aged and elderly people in China. Medicine. 2019;98(10): e14747.

Zhang L, Liu K, Li H, Li D, Chen Z, Zhang LL, Guo LL. Relationship between body mass index and depressive symptoms: the “fat and jolly” hypothesis for the middle-aged and elderly in China. Biomed Res Int. 2016;16(1):1201.

Kim DS, Kim HS, Cho Y, Cho SI: The effects of actual and perceived body weight on unhealthy weight control behaviors and depressed mood among adult women in Seoul, Korea. Journal of preventive medicine and public health = Yebang Uihakhoe chi 2008, 41(5):323–330.

Chaitoff A, Swetlik C, Ituarte C, Pfoh E, Lee LL, Heinberg LJ, Rothberg MB. Associations Between Unhealthy Weight-Loss Strategies and Depressive Symptoms. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(2):241–50.

Doan N, Romano I, Butler A, Laxer RE, Patte KA, Leatherdale ST. Weight control intentions and mental health among Canadian adolescents: a gender-based analysis of students in the COMPASS study. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Ca. 2021;41(4):119–30.

Tiggemann M, Kuring JK. The role of body objectification in disordered eating and depressed mood. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43(Pt 3):299–311.

Schaefer LM, Thompson JK. Self-objectification and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Int J Eat Disord. 2018;51(6):483–502.

Brown AW, Allison DB. Unintended consequences of obesity-targeted health policy. The virtual mentor : VM. 2013;15(4):339–46.

Ramos Salas X: The ineffectiveness and unintended consequences of the public health war on obesity. Canadian journal of public health = Revue canadienne de sante publique 2015, 106(2):e79–81.

Revah-Levy A, Speranza M, Barry C, Hassler C, Gasquet I, Moro MR, Falissard B. Association between Body Mass Index and depression: the “fat and jolly” hypothesis for adolescents girls. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:649.

Bjørngaard JH, Carslake D, Lund Nilsen TI, Linthorst AC, Davey Smith G, Gunnell D, Romundstad PR. Association of Body Mass Index with Depression, Anxiety and Suicide-An Instrumental Variable Analysis of the HUNT Study. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(7): e0131708.

Martin-Rodriguez E, Guillen-Grima F, Aubá E, Martí A, Brugos-Larumbe A: Relationship between body mass index and depression in women: A 7-year prospective cohort study. The APNA study. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists 2016, 32:55–60.

Tashakori A, Riahi F, Mohammadpour A. The Relationship between Body Mass Index and Depression among High School Girls in Ahvaz. Advances in medicine. 2016;2016:3645493.

Lee JH, Park SK, Ryoo JH, Oh CM, Choi JM, McIntyre RS, Mansur RB, Kim H, Hales S, Jung JY. U-shaped relationship between depression and body mass index in the Korean adults. Eur Psychiatry. 2017;45:72–80.

Oh J, Chae JH, Kim TS. Age-specific association between body mass index and depression: The Korea National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2014. Int J Obes. 2018;42(3):327–33.

Lipowska M, Lipowski M. Narcissism as a moderator of satisfaction with body image in young women with extreme underweight and obesity. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(5): e0126724.

Choi JS, Kim JS. Mediating Effect of Body Image Distortion on Weight Loss Efforts in Normal-Weight and Underweight Korean Adolescent Girls. J Sch Health. 2017;87(3):217–24.

Hijji TM, Saleheen H, AlBuhairan FS. Underweight, body image, and weight loss measures among adolescents in Saudi Arabia: is it a fad or is there more going on? Int J Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2021;8(1):18–24.

Orth U, Robins RW, Widaman KF, Conger RD. Is low self-esteem a risk factor for depression? Findings from a longitudinal study of Mexican-origin youth. Dev Psychol. 2014;50(2):622–33.

Zhou J, Li X, Tian L. Longitudinal association between low self-esteem and depression in early adolescents: the role of rejection sensitivity and loneliness Psychol Psychother. 2020;93(1):54–71.

Nguyen DT, Wright EP, Dedding C, Pham TT, Bunders J. Low Self-Esteem and Its Association With Anxiety, Depression, and Suicidal Ideation in Vietnamese Secondary School Students: A Cross-Sectional Study. Front Psych. 2019;10:698.

Orth U, Robins RW, Roberts BW. Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2008;95(3):695–708.

Rieger S, Göllner R, Trautwein U, Roberts BW. Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in the transition to young adulthood: A replication of Orth, Robins, and Roberts (2008). J Pers Soc Psychol. 2016;110(1):e16-22.

Jéquier E. Leptin signaling, adiposity, and energy balance. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;967:379–88.

Lawson EA, Miller KK, Blum JI, Meenaghan E, Misra M, Eddy KT, Herzog DB, Klibanski A. Leptin levels are associated with decreased depressive symptoms in women across the weight spectrum, independent of body fat. Clin Endocrinol. 2012;76(4):520–5.

Almeida OP, Calver J, Jamrozik K, Hankey GJ, Flicker L. Obesity and metabolic syndrome increase the risk of incident depression in older men: the health in men study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17(10):889–98.

Liao W, Luo Z, Hou Y, Cui N, Liu X, Huo W, Wang F, Wang C. Age and gender specific association between obesity and depressive symptoms: a large-scale cross-sectional study BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1565.

Zhou A, Power C, Hyppönen E, Luo H, Li J, Zhang Q, Cao P, Ren X, Fang A, Liao H, et al. Obesity and the onset of depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults in China: evidence from the CHARLS. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):909.

Slater N, Rowley C, Venables RH, White S. Evaluating associations between metabolic health, obesity and depressive symptoms: a prospective analysis of data from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) with a 2-year follow-up. BMC Public Health. 2018;8(12): e025394.

Frisher M, Mulugeta A. Obesity and depressive symptoms in mid-life: a population-based cohort study. BMJ Open. 2018;18(1):297.

Goes VF, Wazlawik E, D’Orsi E, González-Chica DA. Severe obesity increases the prevalence but not the incidence of depressive symptoms in the elderly-population-based cohort in Southern Brazil. International psychogeriatrics / IPA. 2017;29(8):1307–16.

Acknowledgements

We thank the members of the research as well as all participants for their contribution.

Funding

CHARLS was supported by the NSFC (70910107022, 71130002) and National Institute on Aging (R03-TW008358-01; R01-AG037031-03S1), and World Bank (7159234) and the Support Program for Outstanding Young Talents from the Universities and Colleges of Anhui Province for Lin Zhang (gxyqZD2021118).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the research: LZ. Wrote the paper: LZ. Analyzed the data: LZ. Revised the paper: LZ, J-l L, L-l G, L Y, C-z W, TY, Dm Z, JL, Y-x L, LS, X-p L, YH, and H-y C. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All data are openly published as microdata at http://charls.pku.edu.cn/index/zh-cn.html with no direct contact with all participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, L., Li, Jl., Guo, Ll. et al. Weight changes and the incidence of depressive symptom in the middle-aged and older adults: findings from the Chinese nationwide cohort study. BMC Public Health 22, 2282 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14624-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14624-5