Abstract

Background

Female genital circumcision (FGC) is still a challenge in reproductive health. This study investigated socioeconomic disparities in FGC in the Kurdish region of Mahabad, Iran.

Methods

A case-control study was conducted in three comprehensive health centers on 130 circumcised girls as the case group and 130 girls without a history of circumcision as the control group, according to the residential area and the religious sect. The participants completed a previously validated demographic and circumcision information questionnaire. A multivariate logistic regression model with a backward method at a 95% confidence level was used to determine the relationship between socioeconomic variables and FGC.

Results

Multivariate logistic regression showed that a family history of FGC (AOR 9.90; CI 95%: 5.03–19.50), age ranging between 20 and 30 years (AOR 8.55; CI 95%: 3.09–23.62), primary education (AOR 6.6; CI 95%: 1.34–33.22), and mothers with primary education (AOR 5.75; CI 95%: 1.23–26.76) increased the chance of FGC.

Conclusion

The present study provided evidence on socioeconomic factors related to FGC in girls. A family history of FGC, age ranging between 20 and 30 years, and girls’ and their mothers’ education level were strong predictors of FGC. The findings indicate the need to design effective interventions to address these factors to help eradicate FGC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The World Health Organization defines female genital circumcision (FGC) as all methods that harm or remove all or a part of female genital organs for non-medical reasons [1]. FGC is mainly performed in Africa and some parts of the Middle East and Asia. However, FGC prevalence and type vary widely among countries [2]. By 2050, approximately one in every three births will occur in 30 countries in Africa and the Middle East, where FGC is widespread [3, 4]. All this is while short-term consequences of FGC including severe pain, bleeding, genital infection, difficulty in urination, and sepsis, as well as its long-term consequences, including chronic pain and infections, menstrual problems, psychological issues, social isolation, and sanitation problems, are well known [5,6,7,8]. There are various reasons for FGC, but the main reasons are to be found in strong gender discrimination against women, lack of awareness of the negative consequences of circumcision, and cultural traditions and beliefs. Sexual (controlling or reducing women’s sexual desire), social (girl’s entry into womanhood), health (increasing female fertility), and religious beliefs are commonly associated with FGC [8,9,10]. FGC is sometimes such a powerful social norm that forces families to circumcise their daughters, even if they are aware of its consequences, in order not to put their marriage at risk [10].

Many studies have examined socioeconomic and demographic factors influencing FGC prevalence [9, 11, 12]. Although place of residence, education level, religion, and ethnicity appear to be associated with FGC prevalence in a given country, the nature of this relationship varies from country to country. For example, in a recent systematic review by El-Dirani et al., a working mother was found to be protective against FGC in one study, a risk factor of FGC in another study, and statistically insignificant in seven studies. Moreover, higher paternal education was protective against FGC in three studies, while two studies showed no association between paternal education and FGC [11]. Significant changes in the religious arrangement of countries, the interaction between religion with place of residence, local customs, and cultural traditions, and even fear of legal consequences or anti-FGC activities can be the main reasons for the lack of continuous relationship between socioeconomic variables and FGC prevalence [12,13,14].

In Iran, FGC is performed in some southern and western regions [15,16,17]. It should be noted that FGC is commonly carried out in the eastern part of Kurdistan, Iraq [18], along the border with Kurdistan, Iran. Due to the proximity of these two regions and cultural similarities, FGC is also performed in Kurdistan, Iran. It seems that besides ethnic factors, in cities such as Kurdistan with fewer development indicators, the probability of girls undergoing FGC may be related to some socioeconomic factors. Low literacy level and, consequently, low health knowledge level, and living in deprived areas become an essential obstacle for women and their daughters to achieve full health [19].

According to UNICEF, there has been a significant overall decline in FGC prevalence over the last three decades [20]. In some countries, various steps have been taken, such as restricting and banning this practice and increasing public awareness. Iran’s law does not mention FGC specifically; however, there are no statistics on anti-FGC activities in Iran [21]. Efforts to end the tradition have come primarily from activists who speak to families door-to-door, while officials are silent on the matter. Research on FGC is essential to international, national, and local efforts to end the practice. Given the sensitive nature of the practice, conducting these studies in different regions of Iran can be challenging. Research on FGC in Iran is scarce; hence, there is no reliable data about FGC in the country. The first authoritative study adopting the UNICEF approach has found that FGC is being carried out in at least four major provinces of Iran: West Azerbaijan, Kurdistan, Kermanshah in the west, and Hormozgan in the south [22]. Other studies have also reported varying FGC prevalence rates in different regions. Dehghankhalili et al. (2015), in a cross-sectional study on 780 women in Hormozgan, a southern province of Iran, found that 68.5% of women had undergone FGC [15]. Two other cross-sectional studies in the west of Iran by Pashaei et al. (2012) in Ravansar and Bahrami et al. (2018) in Kamyaran reported FGC prevalence of 55.7% and 50.5%, respectively. However, research, especially case-control studies, on disparities related to FGC is scarce. Identifying socioeconomic factors associated with FGC can help decision-makers and health planners design and implement evidence-based interventions to eradicate FGC. This study investigated socioeconomic disparities that determine FGC in a Kurdish region of Iran.

Methods

Study design and participants

The present case-control study was conducted on girls living in Mahabad, a Kurdish region in Iran, in 2018. Mahabad is a green city with a chilly climate in northwest Iran and is about 300km far from the Iran-Iraq border. It has a population of about 133,324 people, and Kurdish is the language predominantly spoken in this region. Muslims living in the Kurdish regions of Iran are mainly “Sunni” in religion and belong to the two sects of Shafi’i and Hanafi.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (IR.UMSHA.REC.1397.379), and performed according to the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all participants, and for girls under 18 years, parent’s or guardian’s consent was obtained prior to the girl’s assent. The participants were assured of the confidentiality of their information. Considering that girls are circumcised at any age, even after puberty and in some cases just before marriage, no age limit was considered in the present study. Accordingly, girls who were not married at the time of sampling and were living in their parents’ house under their support and guardianship were included in the study. Other inclusion criteria were satisfaction with participating in the study, residence in Mahabad City, lack of mental illness, literacy, and ability to understand and speak. Samples not completing more than 10 percent of the questionnaire were excluded from the study.

Sample size

The G*Power software version 3.1.9.7 was used to calculate the sample size. The G*Power software automatically provides the conventional effect size values suggested by Cohen [23]. In this study, considering the medium effect size (odd = 0.5), type I error (α) = 0.05, and power (1-β) = 0.95, total sample size for each group was calculated to be 130 people.

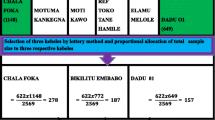

Sampling

In the present study, the research environment was comprehensive health centers, and samples were girls referred for routine check-ups, vaccination, or accompanying others. The samples were drawn through cluster sampling across Mahabad City. In this method, each health center was considered a cluster. First, Mahabad City was divided into three geographical regions (north, south, and center), and sampling was carried out according to the number of health centers in these three regions. We reached a total of six clusters, and three clusters (health centers) were randomly selected. Then, 100 eligible subjects were selected from each health center (50 circumcised girls as the case group and 50 uncircumcised girls as the control group). The information of the case group (circumcised girls) was collected consecutively using a non-probability consecutive sampling method until the required number of cases was obtained. The control group consisted of uncircumcised girls matched for the residential area and the religious sect. Data were gathered by trained local interviewers. Informed consent was obtained from each participant, and the socioeconomic and circumcision information questionnaires were completed by self-report in an appropriate room for this purpose in the health centers.

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable of this study was FGC, defined as cutting and removing all or a part of the clitoris up to the removal of the labia majora. The participants were asked which parts of their genital organs were removed to determine the type of FGC. Since girls are emotional and sensitive, information about the circumcision of girls under 18 was asked from the mother or a reliable companion. It should be noted that all circumcised girls in our study had first-grade genital circumcision, in which the external part of the clitoris is cut.

Independent variables

The independent variables were designed by reviewing previous quantitative studies that examined factors associated with FGC or compared factors between women or girls with FGC to those without FGC [11, 12, 24,25,26]. Associated factors in the individual, parental/household, and community levels were designed as demographic characteristics and circumcision information in a researcher-made questionnaire described below.

Study instrument

The researcher-made questionnaire had two sections:

-

1.

Demographic characteristics included age, education level, occupation, number of family members, birth order, parent’s education, parent’s occupation, family income, and housing status.

-

2.

Circumcision information included age at the time of circumcision, circumciser, place of circumcision, a family history of circumcision, knowledge about female circumcision, and source of information.

The questionnaire items were revised and approved by six reproductive health professionals regarding content validity.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS/18. The chi-square test was used to assess the relationship between the independent variables and FGC. Variables that showed a significant relationship with FGC at the chi-square level were entered in the univariate and then multivariate regression logistic models with the backward method at a 95% confidence level. In the multivariate model, all demographic and socioeconomic variables were entered into the model. Then, each variable was excluded using the backward method, and the model was finalized in step 9. P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographic characteristics

The majority of participants in the case group were 20–30 years old (63.1%), had academic education (43.8%), and were unemployed (45.4%). The cases’ fathers were self-employed (50%), and their mothers were unemployed (66.9%). Both parents had primary education, with a rate of 50% and 66.9%, respectively. The cases belonged to families of 1–5 people (50.6%), had relatively adequate income (49.2%), and were landlords (81.5%). Also, 77.7% of the participants had a history of FGC in their family.

The majority of the participants in the control group were 20–30 years old (53.8%), had academic education (66.2%), and were students (55.4%). The participants’ fathers were self-employed (47.7%), and their mothers were unemployed (73.8%). Also, the participants’ fathers had secondary education (31.5%), and their mother’s had primary education (38.5%). They belonged to families of 1–5 people (56.2%), had relatively adequate income (48.5%), and were landlords (73.1%). Also, 30% of the controls had a history of FGC in their family (Table1).

FGC related characteristics

45% of the girls had been circumcised under five years, and about half of them were the first child in the family. Also, circumcision was performed on more than half of the girls by local women, and more than 90% of them were circumcised at home. 60% of the circumcised girls had information about circumcision, with the Internet being their most common source of information. Most of the girls did not have pain in their circumcision area (Table2).

Socio-economic predictive factors of FGC

The relationship between each demographic and socioeconomic variable with the circumcision status was investigated using the univariate regression model. The results showed that the variables of age, education, occupation, parents’ education, mother’s occupation, and previous history of circumcision in their family were related to an increase in the chance of circumcision. Accordingly, the chance of circumcision was 2.87 [CI 95%; 1.33–6.21] times higher in girls aged 20 to 30 than in those over 30. This chance was 5.28 [CI95%; 1.65–16.85] times higher in girls with primary education than in those with academic education. The probability of circumcision was 0.41 [CI 95%; 1.25–4.69] times more in students than in unemployed women. The chance of circumcision was also 6.96 [CI 95%; 1.87–25.84] and 0.48 [CI 95%; 0.25–0.95] times higher in girls circumcised with mothers with primary education and employed mothers than in girls with academic education and unemployed mothers, respectively. Furthermore, this probability in participants whose fathers had primary education was 5.48 [CI 95%; 2.31–12.97] times. A family history of circumcision increased the odds of female circumcision by 8.12 [CI 95%; 4.65–14.19] times (Table2).

The participants were adjusted regarding occupation, father’s job, father’s education, mother’s job, number of family members, monthly family income, and housing status. Multivariate logistic analysis using the backward method showed that age, education level, mother’s education, and the family history of circumcision were the predictive variables of circumcision. Accordingly, the chance of circumcision was respectively 5.77 [CI 95%; 1.86–17.84] and 8.55 [CI 95%; 3.09–23.62] times higher in girls under 20 and in the age group of 20 to 30 years than in those over 30 years. This change was 6.6 [CI 95%; 1.34–33.22] times higher in girls with primary education than in those with academic education. Also, the chance of circumcision was 5.75 [CI 95%; 1.23–26.76] times higher in girls with mothers with primary education than in girls with mothers with academic education. Also, the family history of circumcision increased the probability of female circumcision by 9.90 [CI 95%: 5.03–19.50] times (Table3).

Circumcision performance related factors

The socioeconomic-related factors, including age at the time of FGC, circumciser, and place of circumcision, were examined. The results showed that age at the time of circumcision was significantly related to the family’s housing status. Thus, circumcision was more prevalent in girls under five years in families who were landlords than in other groups (P = 0.034). Circumcision by local women was also significantly higher in those whose fathers had primary education (P = 0.003) and whose family income was relatively adequate (P = 0.011). The place of the circumcision was significantly related to the father’s occupation and education status. Thus, girls whose fathers had primary education (P = 0.034) and were retired (P = P = 0.024) were more likely to be circumcised at home. The mother’s occupation and education level had no significant relationship with the three circumcision performance-related variables (P > 0/05).

Discussion

About 200million women suffer from mutilation in 30 countries, and more girls are being exposed to circumcision per year due to the increasing rate of population in such countries [2]. According to the results of the present study, a family history of circumcision increased the probability of girls being circumcised by almost ten times. This suggests that FGC is passed from generation to generation within families. A family history of circumcision has had a strong relationship with female circumcision in Kurdistan, Iraq [27]. Also, the systematic review of El-Dirani et al. showed that this variable was a risk factor for FGC in most of the studies [11].

The majority of circumcised girls in our study (45.4%) were circumcised under age five. FGC is usually performed between ages 8 and 14. However, female circumcision cannot be restricted to a specific age, and girls are constantly exposed to circumcision from birth to puberty. EDHS 2008 stated that all female circumcisions were performed before age 15. While the age of circumcision varies between tribes and countries, it seems that Muslims circumcise their daughters at a younger age [28]. Using data for 7,620 women interviewed in the 2003 NDHS, Kandala et al. found that the rate of female circumcision at about five years of age is similar in both urban and rural areas, but circumcision over five years of age seems to be more common in urban areas [29]. A cross-sectional study on 492 people in three refugee camps in Somalia showed that circumcision prevalence increased with age, with 52% and 95% of girls being circumcised at 7–8 and 11–12 years of age, respectively [30]. In our study, FGC was performed by rural women in more than half of the cases and at home in more than 90% of the cases. Consistent with our findings, Pashaei et al., in a cross-sectional study in Ravansar (Iran), found that 96.4% of girls were circumcised by local women at home [15]. Numerous studies have shown that FGC is usually performed by indigenous people with rudimentary tools [31, 32]. However, in some countries, such as Sudan and Egypt, trained midwives and physicians have replaced traditional circumcisers as a way of harm reduction [33, 34]. Al Awar et al., in their cross-sectional study conducted in the United Arab Emirates, reported that 73.7% of circumcision in girls was performed by health professionals/at private clinics [32]. However, the involvement of medical specialists in female circumcision can help prevent the spread of infectious diseases by preventing the use of non-sterile instruments and unnecessary FGC procedures.

In the present study, girls with primary education were circumcised nearly seven times more than those with academic education. The lack of formal education was significantly associated with an increased risk of FGC in several studies [30, 31, 35]. The Egyptian Demographic Health Survey 2008 (EDHS) showed that the probability of circumcision decreased with increasing education level and was higher among women belonging to lower social classes [28]. Also, in a study conducted by Gebremariam et al. (2016) on 679 young female students from Somali, participants’ educational level was a significant independent predictor of circumcision [14]. Other studies have shown that education and self-empowerment are associated with circumcision rejection [36,37,38,39]. For example, a community-based cross-sectional study conducted in Ethiopia showed that uncircumcised women examined in high school or at higher levels did not want to continue circumcision compared to those who were illiterate [40]. In general, education can be interpreted as a form of women’s empowerment that can equalize the balance between them and men [41]. Since circumcision is performed before formal education begins, many believe that the mother’s education level is a more significant variable for assessing the relationship between FGC and education [19]. Mothers’ education is an essential predictor of FGC in young girls, as several studies have reported that as women’s education increases, the incidence of female circumcision decreases and vice versa [19]. In a cross-sectional study by Ali et al. on 3353 young women in Egypt, girls with illiterate parents reported significantly higher rates of circumcision [42]. Gajaa et al. (2014), in a cross-sectional study, determined associated factors of circumcision among daughters in Nigeria. They found that daughters of uneducated mothers were 3.5 times more likely to be circumcised than daughters of educated mothers [43].

Another noteworthy point in the present study is that fathers’ education and occupation, as well as family income, were correlated with the circumciser and the place of circumcision. Thus, girls whose fathers had primary education and were retired and whose family incomes were lower were mostly circumcised by a rural midwife at home. It seems that while low-educated mothers are more likely to circumcise their daughters, low-educated fathers and the low socioeconomic status of the family affect how circumcision is performed. These results show the impact of the socioeconomic level of families on the quantity and quality of female circumcision. Our results highlighted the importance of modifiable variables, such as girls’ and parents’ education (primarily mothers’ education), as predictors of FGC. It is assumed that educated women are primarily aware of their rights and are more capable of demanding and defending these rights for themselves and their daughters. Also, education may reduce women’s dependence and give them greater economic stability.

The main limitation of this study is that the participants were only Kurdish girls living in a Kurdish region in Iran, which impedes the generalization of the study results to other ethnic groups and nationalities. Another limitation of this study is the use of a self-reported questionnaire that increases the chance of recall and social desirability bias. The inclusion criterion of “literacy” may have excluded girls at higher risk of circumcision. In addition, a wide confidence interval is noted in some variables due to the small sample size. Further studies with a larger sample size from different settings are needed to increase the accuracy and generalizability of the findings obtained from this study.

Conclusion

The present study has provided evidence on socioeconomic factors associated with FGC in a Kurdish region of Iran and can help design effective interventions to eradicate this harmful practice. A family history of FGC, age of 20–30 years, and education level of girls and their mothers were found as predictors of FGC. Considering these strong predictive factors, we recommend targeted interventions based on addressing the modifiable variable. Accordingly, empowering women by creating education opportunities can lead to the success of global efforts to fight and eradicate FGC.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed for this study are available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- FGC:

-

Female Genital Circumcision

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- UNICEF:

-

United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund

References

Shafaati Laleh S, Maleki A, Samiei V, Roshanaei G, Soltani F. The comparison of sexual function in women with or without experience of female genital circumcision: A case-control study in a Kurdish region of Iran. Health Care Women Int. 2021;2:1–13.

World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation. Fact sheet No 241. Updated January; 2022. http:// www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs241/en/.

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A global concern. New York: UNICEF; 2016.

Muteshi JK, Miller S, Belizán JM. The ongoing violence against women: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. Reprod Health. 2016;13:44.

Berg RC. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting. In: The Encyclopedia of Women and Crime; 2019. p.1–6.

Obiora OL, Maree JE, Mafutha N. Female genital mutilation in Africa: scoping the landscape of evidence. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2019; 1–12.

Klein E, Helzner E, Shayowitz M, Kohlhoff S, Smith-Norowitz TA. Female Genital Mutilation: Health Consequences and Complications-A Short Literature Review. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2018 Jul 10; 2018:7365715.

Rushwan H. Female genital mutilation: a tragedy for women’s reproductive health. Afr J Urol. 2013;19(3):130–3.

Ahinkorah BO. Factors associated with female genital mutilation among women of reproductive age and girls aged 0–14 in Chad: a mixed-effects multilevel analysis of the 2014–2015 Chad demographic and health survey data. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):286.

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Female genital mutilation/cutting. 2015. http://www.unicef.org/protection/57929_58002.html. Accessed February, 7, 2016.

El-Dirani Z, Farouki L, Akl C, Ali U, Akik C, McCall SJ. Factors associated with female genital mutilation: a systematic review and synthesis of national, regional and community-based studies. BMJ Sex Reprod Health. 2022;48(3):169–78.

Geremew TT, Azage M, Mengesha EW. Hotspots of female genital mutilation/cutting and associated factors among girls in Ethiopia: a spatial and multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):186.

The United Nations International Children’s Emergency Fund. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: A Statistical Exploration 2005. New York: The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF); 2005. http://www.unicef.org/publications/files/FGM-C_final_10_October.pdf.

Gebremariam K, Assefa D, Weldegebreal F. Prevalence and associated factors of female genital cutting among young adult females in Jigjiga district, eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional mixed study. Int J Womens Health. 2016;8:357–65.

Van Rossem R, Meekers D. The decline of FGM in Egypt since 1987: a cohort analysis of the Egypt Demographic and Health Surveys. BMC Womens Health. 2020;20(1):100.

World Health Organization. Violence info Islamic Republic of Iran 2014. Available from: https://apps.who.int/violence-info/ country/IR.

Dehghankhalili M, Fallahi S, Mahmudi F, Ghaffarpasand F, Shahrzad ME, Taghavi M, et al. Epidemiology, Regional Characteristics, Knowledge, and Attitude Toward Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting in Southern Iran. J Sex Med. 2015;12(7):1577–83.

Pashaei TA, Rahimi A, Ardalan A, Felah A, Majlessi F. Related factors of female genital mutilation (FGM) in Ravansar (Iran). J Women’s Health Care. 2012;1(2):108.

Bahrami M, Ghaderi E, Farazi E, Bahramy A The prevalence of female genital mutilation and related factors among women in Kamyaran, Iran. Chorionic Disease Journal. 2018;6(3):113–119. Available from: https://www.sid.ir/en/journal/ViewPaper.aspx?id=658368.

Shabila NP. Changes in the prevalence and trends of female genital mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan Region between 2011 and 2018. BMC Women’s Health 2021; 21 (137). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01282-9.

Soltani F, Shafaati S, Aghababaei S, Samiei V, Roshanaei G. The effectiveness of group counseling on prenatal care knowledge and performance of pregnant adolescents in a Kurdish region of Iran. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2018;33(2). doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/ijamh-2018-0108.

Ahmady K. Prevalence of female genital mutilation/cutting in Iran. SJSSH. 2015;1(3):28–42.

Kang H. Sample size determination and power analysis using the G*Power software. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2021;18:17.

Pashaei T, Ponnet K, Moeeni M, Khazaee-pool M, Majlessi F. Daughters at Risk of Female Genital Mutilation: Examining the Determinants of Mothers’ Intentions to Allow Their Daughters to Undergo Female Genital Mutilation. PLoS One. 2016 Mar;31(3):e0151630.

Andualem M. Determinants of Female Genital Mutilation Practices In East Gojjam Zone, Western AmharaMHARA, ETHIOPIA. Ethiop Med J. 2016 Jul;54(3):109–16.

Sakeah E, Debpuur C, Oduro AR, Welaga P, Aborigo R, Sakeah JK, Moyer CA. Prevalence and factors associated with female genital mutilation among women of reproductive age in the Bawku municipality and Pusiga District of northern Ghana. BMC Womens Health. 2018 Sep;18(1):150.

Yasin BA, Al-Tawil NG, Shabila NP, Al-Hadithi TS. Female genital mutilation among Iraqi Kurdish women: a cross-sectional study from Erbil city. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:809.

El-Zanaty F, Way AA. Egypt demographic and health survey 2008. Calverton, Maryland, USA: Ministry of Health and Population [Arab Republic of Egypt], National Population Council [Arab Republic of Egypt], and ORC Macro; 2009.

Kandala NB, Nwakeze N, Kandala SN. Spatial distribution of female genital mutilation in Nigeria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81(5):784–92.

Mitike G, Deressa W. Prevalence and associated factors of female genital mutilation among Somali refugees in eastern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:264.

Ali S, de Viggiani N, Abzhaparova A, Salmon D, Gray S. Exploring young people’s interpretations of female genital mutilation in the UK using a community-based participatory research approach. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1132.

Al Awar S, Al-Jefout M, Osman N, Balayah Z, Al Kindi N, Ucenic T. Prevalence, knowledge, attitude and practices of female genital mutilation and cutting (FGM/C) among United Arab Emirates population. BMC Womens Health. 2020 Apr;22(1):79.

Shell-Duncan B, Njue C, Moore Z. Evidence to End FGM/C: Research to Help Women Thrive. New York: P. Council; 2017. The Medicalization of Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: What do the Data Reveal.

Shell-Duncan B. The medicalization of female “circumcision”: harm reduction or promotion of a dangerous practice? Soc Sci Med. 2001;52(7):1013–28.

Gholami A, Moghadami N. Possible Crimes in Female Circumcision and the Need for its Criminalization. Med Law J. 2018;12(45):59–85.

Waigwa S, Doos L, Bradbury-Jones C, Taylor J. Effectiveness of health education as an intervention designed to prevent female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): a systematic review. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):62.

Abathun AD, Gele AA, Sundby J. Attitude towards the Practice of Female Genital Cutting among School Boys and Girls in Somali and Harari Regions, Eastern Ethiopia. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2017; 2017:1567368.

Williams-Breault BD. Eradicating Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Human Rights-Based Approaches of Legislation, Education, and Community Empowerment. Health Hum Rights. 2018;20(2):223–33.

Ameyaw EK, Yaya S, Seidu AA, Ahinkorah BO, Baatiema L, Njue C. Do educated women in Sierra Leone support discontinuation of female genital mutilation/cutting? Evidence from the 2013 Demographic and Health Survey. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):174.

Bogale D, Markos D, Kaso M. Intention toward the continuation of female genital mutilation in Bale Zone, Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health. 2015;7:85–93.

Baheiraei A, Soltani F, Ebadi A, Rahimi Foroushani A, Cheraghi MA. Risk and protective profile of tobacco and alcohol use among Iranian adolescents: a population- based study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2017;29(3):20150089.

Ali HAAEW, Arafa AE, El FAbdA Shehata, Fahim NA. AS. Prevalence of Female Circumcision among Young Women in Beni-Suef, Egypt: A Cross-Sectional Study. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2018;31(6):571–4.

Gajaa M, Wakgari N, Kebede Y, Derseh L. Prevalence and associated factors of circumcision among daughters of reproductive aged women in the Hababo Guduru District, Western Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Womens Health. 2016;16:42.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely appreciated from financial support of Research Deputy of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences. In addition, all participants and personnel in health care centers who helped in the research process are appreciated.

Funding

This work was supported by Vice-chancellor for Research and Technology, Hamadan University of Medical Sciences of Iran [Grant number 9706063438].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SSL and FS: study concept and design, and acquisition of data analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. GR: analysis and interpretation of data and drafting of the manuscript. FS, SSL, FGM and GR: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content; FS: study supervision. The manuscript has been read and approved by all the authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and.

was approved by the ethics committee of the Research Council of Hamadan University of Medical Sciences (IR.UMSHA.REC.1397.379). Written consent was obtained from the participants, and they were assured of the confidentiality of their information.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Laleh, S.S., Roshanaei, G., Soltani, F. et al. Socio-economic disparities in female genital circumcision: finding from a case-control study in Mahabad, Iran. BMC Public Health 22, 1877 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14247-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-022-14247-w